Sample Internal Migration in Developing Countries Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

There is widespread agreement among students of population on both the importance of migration for social and demographic dynamics and the difficulty that, by its multifaceted nature, its study raises for the researcher. The intensification of migratory movements always implies societal transformations, including the accentuation of regional and social inequalities, modifications in patterns of population distribution, and changed demographic profiles in both origin and destination areas. Migration studies, however, are complex. The definition of the term itself and its measurement and interpretation are not straightforward. Depending on the type of migration and the focus of the analysis, very diverse theoretical approaches have been used.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

As a component of demographic growth, migration plays a fundamental role in the rapid growth of developing countries’ large cities, as well as producing significant alterations of the population’s distribution over its territory. Migration is responsible, therefore, for a considerable part of the demographic concentration which characterizes many of these countries.

All of the studies concerned with measuring the role of migration show that, to a great extent, it was the volume of movements from rural to urban areas which explains the intense rhythm of urban population increase in the second half of the twentieth century. However, considering its multiple facets, internal migration is not restricted to rural–urban movements, since other types may emerge and grow in importance as a result of changes in economic and sociocultural contexts and in spatial configurations, as well as resulting from specific historical moments of differing countries. This is why, especially in Latin America, types of movements typical of developing countries, such as rural–urban or rural–rural migration, coexist in the same territories with types observed in developed countries, such as urban–rural and urban–urban migration. These movements reflect new forms of organization and structuring of space.

2. Definition And Data Sources

The difficulties of studying migration begin with its definition. Unlike mortality and fertility, this demographic phenomenon has no single definition, but varies according to historical context and the spatial and temporal referents chosen. In fact, even when migration is considered, in a general way, as the move of an individual from one geographic unit (generally defined in administrative terms) to another and as involving a change in usual residence (United Nations 1970, Bilsborrow 1998b, Oucho 1998, Courgeau 1988), several questions remain for such a definition to be used empirically. On the one hand, the type of geographic unit and the boundaries which define it must be specified. The rural/urban dichotomy is one of the most commonly used distinctions, although movements between municipalities, states, or large regions are also important. From the point of view of the spatial dimension, then, migration admits several definitions.

As if this were not enough, another element must be considered for a correct definition of migration: time (Bilsborrow 1998b). What constitutes a change of residence? How long must a person remain in the place of destination to consider the move as definitive and, therefore, a change of residence? These are not easy questions to answer, a situation reflected in another difficulty with migration: its measurement. Although international organizations such as the United Nations endeavor to convince countries to adopt minimum criteria which would guarantee the comparability of data, through recommendations and manuals (United Nations 1970), the measurement of migration is problematic. This is so, not only because of the considerable variation in the number and size of territorial divisions among and within countries, but also because of the various possible movements which these divisions may capture.

Classic data sources, such as the demographic censuses, due to space limitations in the questionnaires and to financial constraints, must generally decide which type of question or territorial division to use for the migration question, when and if it is possible to include this dimension in the questionnaire. There are other problems as well, such as the temporal gaps of censuses, precarious data publication in many countries (Oucho 1998, Chen et al. 1998, Bilsborrow 1998b, Lattes 1998), and financial and operational difficulties for carrying out specific and periodic surveys, sources which would be the most adequate to obtain a better understanding of the phenomenon, especially of its determinants and consequences (Bilsborrow et al. 1984).

Problems of periodicity, availability, quality, and publication of data have meant that much of the information on migration is obtained through the use of indirect demographic estimation techniques, a fact which not only limits analytic possibilities but also affects the reliability and precision of results.

3. The Role Of Rural–Urban Migration In The Urbanization Process

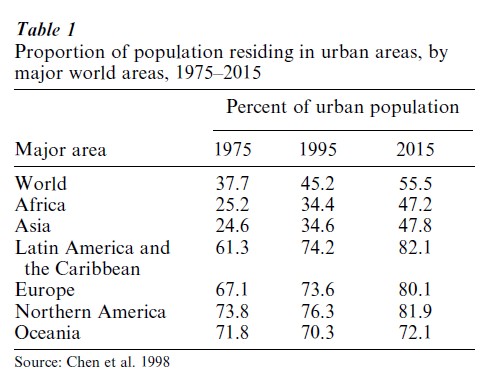

The twentieth century ended with more than half of the world’s population living in urban areas. Nevertheless, there remain considerable differentials among countries in this respect, especially between developed and developing countries. While European and North American countries have proportions of urban population over 70 percent, and are likely to pass 80 percent by 2015 according to United Nations estimates (Chen et al. 1998), in Africa these values are under 35 percent and will not reach 50 percent even by 2015. There are, of course, important differences among developing countries. In Latin America, the region with the highest level of urbanization—especially in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, and Venezuela—close to 80 percent of the population live in cities. Table 1 presents estimates of the proportion of urban population residing in major world areas.

Comparing data on rural and urban population is problematic, however, and precaution should be taken, since this definition depends on each country (Bilsborrow 1998b, Lattes 1998). There is no doubt, however, that the developing world is on the path of increasing concentration of population in cities.

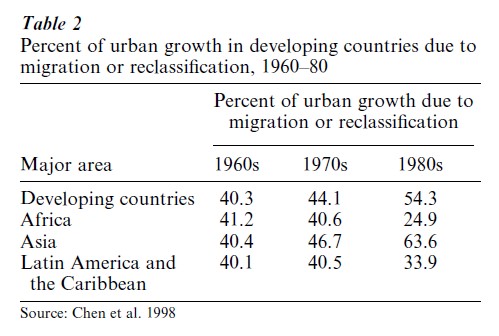

In this continuous process of urbanization, internal migration of rural origin plays an important role, especially considering that the higher level of rural fertility favors greater natural growth in these areas, therefore having an inverse effect. Authors such as Chen, Valente, and Zlotnik (1998), Lattes (1998), and Lucas (1997) leave no doubt as to the preponderant weight of migratory movements from rural areas to the growth of cities in developing countries.

Table 2 shows much variation, however, in the relative contribution of migration and reclassification to urban growth in developing countries. Unfortunately, in view of the lack of adequate data, existing estimates of the effect of migration on urban growth, having been obtained by residual methods—the difference between total observed growth and estimated natural growth—do not permit separating the effect of reclassification of rural to urban areas, which also contributes to the increase of urban population. For the majority of countries for which data exist, the combined contribution of migration and reclassification is greater than 40 percent. Lucas (1997) shows that for a sample of 29 countries this proportion reached 41.4 percent in the 1960s.

The more countries urbanize and the more complex and heterogeneous are their social, economic, cultural, and political structures, the more diversified are the types of population mobility. As Bilsborrow notes, the emphasis of migration research on the rural–urban type reveals ‘a severe case of myopia,’ since ‘this bias is inconsistent with reality’ (Bilsborrow 1998b, p. 8). Indeed, besides the several variants of internal migration in terms of the temporal dimension (permanentorshort-termmoves—seasonal,temporary,and circular (see Bilsborrow 1998b)), the spatial perspective also leads to other considerations, such as migration of urban origin.

In fact, phenomena such as ‘counter-urbanization’ (Champion 1989, Frey 1988, Lattes 1998), ‘rural rebound’ (Johnson 1999), and ‘nonmetropolitan turnaround’ (Fuguitt 1985), typical of developed countries, are already felt in developing countries, especially in Latin America. In addition, there are phenomena typical of developing countries. On the one hand, the settlement of frontier regions implies migration to rural areas, while on the other hand, demographic pressure in stagnating areas, concentration of land ownership and technological and organizational changes in agriculture dislocate population from rural zones. At the same time, the peripheral growth of metropolitan areas encompasses a large variety of urban–urban and urban–rural movements, which become increasingly visible and significant in these countries, especially as urbanization reaches high levels.

Rural–rural movements should not be underestimated either, least of all in some countries of Asia and Africa, where the proportion of population living in rural areas continues to be high. Skeldon (1986) shows, for example, that for India, 57.4 percent of those who had moved in the 10 years before the 1981 census did so from one rural area to another, while other types of movement were less important: rural–urban (19.5 percent), urban–urban (15.2 percent), and urban–rural (7.9 percent). Refugee movements, driven by war and environmental disaster, continue to displace populations, often resulting in permanent dislocations; such movements are rarely examined by students of internal migration.

For the largest cities, it is not only the movements originating in the less developed regions which are important. Both intra-metropolitan moves, responsible for a major part of the growth of urban peripheries (Cunha 1998), and commuting, whose growth reflects growing distances between residence and workplace, are significant features of urban life in developing countries.

4. Characteristics And Conditioning Factors Of Migration

In view of the multifaceted character and the many forms of the migratory phenomenon, its characteristics and conditioning factors are also considerably varied, depending, on the one hand, on whether one adopts a macro or micro level of analysis, and on the other hand, the historical moment and the economic, social, political, and cultural context in which migration occurs. Thus, conditioning factors will vary and characteristics of population movements between distant regions of a country, with different degrees of development, will certainly be distinct from those referring to moves between municipalities of a metropolitan area.

Although in terms of age and sex there are regular references in the literature concerning the tendency for migration to be concentrated among young adults, in general between the ages 15–30 years, and concerning a greater proportion of women in rural–urban streams (United Nations 1993), these generalizations are very abstract and therefore incapable of capturing the entire range of possibilities encompassed by this complex phenomenon. There are social-structural factors which condition movements, as well as specific cultural aspects and geographic realities (the distances involved in the migration, for example). Such elements as life cycle, the composition and forms of family organization and characteristics of origin and destination areas are fundamental elements for determining who moves and who stays.

In terms of migration by age, selectivity reveals the importance of economic factors, especially those associated with the forms and possibilities of the insertion of the individual in the local labor market (both in terms of employment and remuneration). The greater predominance of young adults reveals a greater incidence of movements of one person or of couples in early stages of their life cycles. From the point of view of destination areas, migration will depend also on pull factors. For large urban centers, for example, selectivity will be affected by the number of opportunities available in the formal and informal labor markets.

With the restructuring of the world economy, with the accompanying flexibilization of production and employment and the ever more intense use of technology and information (Castells 1996, Harvey 1990), the employment migration relation will not be as strong as in the past. The levels of wealth in urban areas, creating a demand for unskilled personal services, will continue to attract migrants, able to survive on irregular odd jobs, with no prospect for real employment. On the other hand, in agricultural frontier areas, for example, family migration is more likely to predominate, which would alter the age structure of migration, making it less selective.

As for sex, the available data (United Nations 1993) show that although women predominate in rural– urban migration streams, this tendency is not so clear when data from different countries are observed, especially controlling for age. Even in African countries, where the predominance of male migration is clear, controlling for age makes a difference: in the 10–19 and over 45 categories, women dominate, while in the highly productive ages, it is men who migrate more (Singelmann 1993). The fact that younger women represent greater proportions may be explained by the differences between the ages of men and women within marriage; for older women the data probably reflect the effect of differential mortality by sex which, as is well-known, favors women. This means that for the sex variable also, migration characteristics depend greatly on the contexts in which they occur and any generalization may be, to say the least, simplistic.

In addition to factors linked to the needs and preferences of migrants or to the structural conditions of origin and destination areas, the role of social networks must also be considered among the major conditioning factors of migration. Networks, of fundamental importance in the direction and volume of streams, supply information on destinations; reduce risk; and facilitate adaptation of the individual to the new area.

5. Conclusions

The late twentieth century was marked by immense population movement between regions of developing countries, especially by rural–urban migration. A slowdown in technological development in these countries at the century’s end, coupled with increasing productivity in agriculture, point to a change of pace in these movements. According to Brockerhoff (1999, p. 772): ‘the sluggish performance of manufacturing (compared to agriculture) remains largely responsible for the observed slower pace of urban growth in developing countries, and may have decelerated urban growth from what otherwise would have been higher rates in the 1980s and 1990s by curbing net rural-tourban migration.’

The beginning of the twenty-first century is marked by a radically altered situation. Globalization, in both its economic and sociocultural aspects, together with the demographic transition and the environmental crisis, have greatly affected the factors which condition population mobility. The most intense phase of urbanization has been completed in many countries. The mobility and flexibility of multinational capital have weakened the relation between place of residence and place of work. New forms of mobility become more important: commuting, tourism, circular migration, and seasonal migration, in addition to the increase in short-distance, intermunicipal moves. International migration, which in the nineteenth century implied a permanent move of large populations, has become an option not radically different from internal migration, and nearly as reversible. The rapid population growth phase of the demographic transition, which contributed to internal migration, has also given way to slower growth in many countries, reducing pressures in places of origin. Finally, an ‘empty world’ has been substituted by a ‘full world’ and the resulting environmental restrictions will be ever more important conditioning factors of population mobility (Hogan 1993).

Policy responses to internal migration in developing countries have varied widely. Desires to colonize new agricultural regions, to promote industrialization or to curb what is perceived as excessive growth of ‘mega-cities’ have led governments to adopt a wide range of policies. The success of such policies has often been questioned, although Brockerhoff (1999) observes that countries which expressed an intention to effect policies for slower urban growth, such as Mexico, Egypt, and India, have had lower urban growth rates than their global subregions and especially lower than their neighbors. In the coming period of slower demo-graphic growth, policy initiatives may be more generally successful.

The diversity which is currently observed in the world demographic situation has no historical precedent. Rates of internal migration and urbanization levels are extremely varied, but the tendencies in all major regions point to convergence and a less varied situation in the future.

Bibliography:

- Bilsborrow R E (ed.) 1998a Migration, Urbanization and Development: New directions and issues. UNFPA Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA

- Bilsborrow R E 1998b The state of the art and overview of the chapters. In: Bilsborrow R E (ed.) Migration, Urbanization and Development: New directions and issues. UNFPA Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA

- Bilsborrow R E, Oberai A S, Standing G 1984 Migration Surveys in Low-income Countries: Guidelines for Survey and questionnaire design. Croom Helm, London

- Brockerhoff M 1999 Urban growth in developing countries: A review of projections and predictions. Population and Development Review 25(4): 757–78

- Castells M 1996 The Rise of the Network Society. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Champion A G (ed.) 1989 Counterurbanization: The changing pace and nature of population deconcentration. Arnold, London

- Chen N, Valente P, Zlotnik H 1998 What do we know about recent trends in urbanization? In: Bilsborrow R E (ed.) Migration, Urbanization and Development: New Directions and Issues. UNFPA Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA

- Courgeau D 1988 Methodes de mesure de la mobilite spatiale: migrations internes, mobilite temporaire, navettes. [Methods for measuring spatial mobility: internal migration, temporary migration, commuting]. Editions de Institut National d’Etudes Demographiques, Paris

- Cunha J M P 1998 New trends in urban settlement and the role of intraurban migration: The case of Sao Paulo Brazil. In: Bilsborrow R E (ed.) Migration, Urbanization and Development: New directions and issues. UNFPA Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA

- Frey W H 1988 Migration and metropolitan decline in developed countries: A comparative study. Population and Development Review 14(4): 595–628

- Fuguitt G V 1985 The nonmetropolitan population turnaround. Annual Review of Sociology 11: 259–80

- Harvey D 1989 The Condition of Postmodernity. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Hogan D J 1993 Population Growth and Distribution: their relations to development and the environment. Background Paper DDR 5. United Nations, CELADE, Santiago

- Johnson K 1999 The rural rebound. Reports on America 1, 3. Population Reference Bureau, Washington, DC

- Lattes A 1998 Population Distribution in Latin America: Is there a trend towards population deconcentration? In: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Population Distribution and Migration. United Nations, New York

- Lucas R E B 1997 Internal migration in developing countries. In: Rosenzweig M R, Stark O (eds.) Handbook of Population and Family Economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam

- Oucho J O 1998 Recent internal migration processes in Sub-Saharan Africa: Determinants, consequences, and data adequacy issues. In: Bilsborrow R E (ed.) Migration, Urbanization and Development: New directions and issues. UNFPA Kluwer Academic Publishers, Norwell, MA

- Singelmann J 1993 Level and trends of female internal migration in developing countries, 1960–1980. In: United Nations Internal Migration of Women in De eloping Countries. United Nations, New York

- Skeldon R 1986 On migration patterns in India during the 1970s. Population and Development Review 12(4): 759–79

- United Nations 1970 Methods of Measuring Internal Migration. Manuals on Methods of Estimating Population, Manual VI. United Nations, New York

- United Nations 1993 Internal Migration of Women in De eloping Countries. United Nations, New York