View sample sociology research paper on social problems in the US. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The study of social problems in the United States is no doubt one of the most difficult to summarize and analyze within sociology. In contrast to family sociology, criminology, social stratification, the sociology of sport, and so on, the study of social problems is always shifting in terms of what is included or excluded as the focus of study. But there is also the matter of shifting perspectives and theories within all the core issues within the field of social problems, such as racial discrimination, crime and delinquency, and sexual deviance, to name only a few of what have been among the core issues in the study of social problems in America.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In what follows, we will briefly consider how social problems have been studied in early American history and then consider how social problems have been defined in sociology textbooks and look at the trends in these textbooks over the years. In the second half of this research paper, we will examine more critically how the particular pattern of American values have influenced our definitions of social problems, along with the impact of wealth and power on these definitions. With this examination of wealth and power, we will consider the impact of social movements on what comes to be defined as social problems. A complete understanding of the impact of social movements, however, also requires brief consideration of the causes of social movements. Finally, we will consider how solutions to social problems are also shaped by power, wealth, and American value orientations.

A Brief History of the Study of Social Problems in the United States

The first book in the United States with the title Social Problems was mostly likely that by Henry George, first published in 1883 (George 1939). But sociologists such as George Herbert Mead were already discussing the nature of social problems and the need for social reform in the late 1800s (see Mead 1899; Schwendinger and Schwendinger 1974:452–56). As industrialization took off dramatically in the final two decades of the nineteenth century, so did many conditions that came to be defined as social problems, such as urban poverty, unemployment, and crime. As the great historian Hofstader (1955) noted, it was soon after this that the United States entered one of its reoccurring cycles of reform movements (also see Garraty 1978). It was also a time when sociology was emerging as a major discipline of academic study in the United States (Gouldner 1970; Schwendinger and Schwendinger 1974). The timing of these two events is no doubt a reason why the study of social problems became one of the major subareas in American sociology. But it was also the unique set of utilitarian and individualistic values in the United States that affected the development of American sociology. A crusading spirit accompanied the emergence of American sociology, with many of the early American sociologists coming from Christian clergy backgrounds to a new secular orientation toward understanding the problems of the newly industrialized nation (Gouldner 1970).

It was also a liberal critique of the American society rooted in the early discipline of U.S. sociology, different from that found in European sociology. From the midnineteenth century, European sociology had developed with the full range of perspectives, from radical critiques of basic institutions provided by Marx to conservative support of the status quo from the likes of Herbert Spencer. American sociology through the first half of the twentieth century, in contrast, “came to dwell on those concrete institutional areas and social problems” (Gouldner 1970:93) accepted by the dominate society from a perspective of how to make them work better rather than suggesting basic change. “Indeed, nothing like Marxian sociology was even recognized by American sociology until well after World War II” (McLellan 1973). There were, of course, Marxian perspectives among European immigrants and the early labor movement in the United States, but little of this found its way into academic halls. It is telling that Talcott Parsons’s major book, designed to introduce Americans to European sociology in the early 1930s, had not one mention of Marx or Marxian theory (Parsons 1937). To this day, social problems are not considered a major subarea in European sociology or offered as a course in many European universities. The exception to this was sociology in the old Soviet Union, where the Soviet government found the social problem orientation of functional sociology a useful perspective for “fine-tuning” the Soviet society without criticism of the basic Soviet institutions (Gouldner 1970:447–52).

What is a Social Problem? Textbook Definitions

Standard “textbook” definitions of social problems are generally grouped into three categories, with the second two categories most often used by sociologists themselves. As we will consider in the following, however, there are many more underlying assumptions about the nature of society and humans that shape what sociologists as well as the general public come to define as social problems.

The public generally sees a social problem as any condition that is harmful to society; but the matter is not so simple, for the meanings of such everyday terms as harm and society are far from clear. Social conditions that some people see as a problem harm some segments of society but are beneficial to others. Take trade policy as an example. Shareholders and others affiliated with multinational corporate manufacturers typically argue that any kind of trade restriction is a problem because government regulation interferes with the free enterprise system and drives up costs to consumers. On the other hand, domestic workers and manufacturers argue that the government’s failure to exclude products produced in low-cost nations is a social problem because it costs jobs and hurts domestic business. As we will discuss in more detail later, one person’s social problem, in other words, is often another person’s solution. In fact, most people and organizations define something as a social problem only if it harms (or seems to harm) their own interests.

Sociologists have tried to take a less biased approach with mixed results. Most of the early sociological works on social problems held that a social problem exists when there is a sizable difference between the ideals of a society and its actual achievements. From this perspective, social problems are created by the failure to close the gap between the way people want things to be and the way things really are. Thus, racial discrimination is a social problem because although we believe that everyone should receive fair and equal treatment, some groups are still denied equal access to education, employment, and housing. Before this definition can be applied, however, someone must first examine the ideals and values of society and then decide whether these goals are being achieved. From this perspective, sociologists and other experts thus decide what is or is not a problem because they believe they are the ones with the skills necessary for measuring the desires and achievements of society (see Merton and Nisbet 1971).

Critics of this approach point out that no contemporary society has a single, unified set of values and ideals. When using this definition, sociologists must therefore decide which standards they will use for judging whether or not a certain condition is a social problem. Critics charge that those ideals and values used as standards are selected on the basis of the researcher’s personal opinions and prejudices, not objective analysis.

The “social constructivists,” who have become the dominant school in social problems research, take a different position, holding that a social problem exists when a significant number of people believe that a certain condition is in fact a problem. Here, the public (not a sociologist) decides what is or is not a social problem. The sociologist’s job is to determine which problems affect a substantial number of people. Thus, in this view, pollution did not become a social problem until environmental activists and news reports attracted the public’s attention to conditions that had actually existed for some time (see Blumer 1971; Spector and Kitsuse 1973).

The advantage of this definition is that it does not require a value judgment by sociologists who try to decide what is and is not a social problem: Such decisions are made by “the public.” However, a shortcoming of this approach is that the public is often uninformed or misguided and does not clearly understand its problems. If thousands of people were being poisoned by radiation leaking from a nuclear power plant but didn’t know it, wouldn’t that still be a social problem? A potentially more serious shortcoming of this approach is its hidden political bias. Obviously, in a mass society it is not simply the seriousness of the problem that wins it public attention but the way the corporate media present it. Furthermore, relatively powerless groups with little money or political organization are not able to get their problems recognized as social problems in the way that dominant groups can. Sociologists using the constructivist approach in the study of social problems creation have generally been very sensitive to the role power plays in this process, but researchers focusing more narrowly on individual social problems have often unreflectively accepted the definitions of problematic conditions provided by funding agencies or popular opinion (Galliher and McCartney 1973; Useem 1976a, 1976b; Kerbo 1981, 2006a:254–59).

But even these conflicting views of how social problems are to be defined miss important underlying assumptions that influence what people come to define as a social problem. These underlying assumptions account for how social problems are differently conceived across societies, through history, and across lines such as race, class, and religion within societies at one particular time. And it must be recognized that sociologists have also been influenced by these underlying and often hidden assumptions about humans and societies.

The Field Today: Trends in “Social Problems” Textbooks

The question of which problems are serious enough to warrant sociological attention has been a difficult and controversial one over the years. We will consider this issue from another perspective in the following. But for now, we can note that the pressure of social movements is one of four interwoven factors that determined which problems draw the most sociological attention. The public’s perception of its problems is a second important factor that, of course, is strongly influenced by the media of mass communication. Space does not permit an exploration of all the factors that influence the media’s decisions to turn its attention on one problem and not another, but certainly the corporate interests of the media conglomerates and the various political and financial pressures to which they are exposed are of prime importance (see, for example, Domhoff 2006, on the “policy formation process”). But in addition to the media, the public’s perception of social problems is also shaped by the actual experiences of everyday people. So a third factor is the social crises that have a wrenching impact on the public from time to time, as well as the ongoing contradictions of industrial capitalism. In January of 2001, for example, terrorism was not mentioned as a major problem in the Gallup Poll, but by the start of 2002, it was the number one problem identified by the respondents. With the start of the Iraq war the following year, warfare and international tension replaced terrorism on the list of national concerns. In 2001, less than 0.5 percent of the poll respondents mentioned warfare and international tensions as the nation’s most serious problem, but by 2003, 35 percent did so (Gallup 2004). A final factor involves the sociologists who are selecting the problems for consideration.

Since most practicing sociologists hold some kind of academic position, they function as semi-independent intellectuals in the arena of social problems creation. As such, they have considerably more independence (although less visibility and influence) than scientists and advocates working for the corporations or other special interest groups. But as noted in the foregoing, they are, nonetheless, still constrained by the need to obtain financial support for their research and the political climate of their universities. The paradigmatic shift that has occurred in sociology in the last 50 years as it moved away from the functionalist perspective to a more critical conflict orientation has certainly been an important influence both in the problems that are given attention and in the ways in which they are analyzed.

Since the focus of ociological research itself is determined as much by the priorities of the funding agencies as by the sociologists who carry it out, one of the best guides to the changes in sociological concerns is the content of the social problems textbooks. A comparison of contemporary texts with those from the earlier decades of the postwar era shows that although organizational styles and definitions vary, there is a significant group of problems that have maintained consistent sociological attention. If any social problems can be said to occupy the center of sociological concern, they are the ones related to crime and deviance. Certain types of crime and deviance were given more coverage in one era than another, but all the major texts have an extensive coverage of this topic. Other constants are the problems of the family, ethnic relations, population, and poverty or economic inequality. A second group of problems appears in some texts but not in others without any clear chronological pattern of increasing or decreasing attention. Surprisingly, given their importance in public opinion polls, economic problems other than poverty are not consistently covered. Other problems in this category include those of urbanization, sexuality, and education.

Finally, a third group of problems has shown an increase or decrease in sociological interest over the years. The first edition of the best-selling text by Horton and Leslie (1955) had chapters on two problems that are not seen in later texts: “Religious Problems and Conflicts” and “Civil Liberties and Subversion” (the focus of the latter being primarily on the dangers of communism). New social movements during this period also brought new problems to the foreground. By the time Joseph Julian’s text replaced Horton and Leslie as the top seller in the 1970s, several new problems had joined the core of sociological interest. In response to the rise of the environmental movement, Julian’s (1973) first edition contained a chapter on environmental problems—something that became a mainstay of social problems texts either on its own or with a presentation of population growth as a social problem. The feminist movement succeeded in adding another critical topic— gender inequity—to the mainstream texts. The extremely influential text, edited by Robert K. Merton and Robert Nisbet (1976), first added a chapter on gender in its fourth edition, and Julian (1977) added a similar chapter the following year. More recently, there has been growing attention to the problems faced by gays and lesbians, even though this topic has generally not been treated in an independent chapter of its own. Although chapters on the problems of aging are not quite as common, they also started showing up around the 1970s.

The main focus of most of these texts, like that of American sociology itself, has been on domestic issues, but there have been some important changes there as well. As the memories of World War II began to fade, there was some decline in interest in events beyond America’s borders. Horton and Leslie originally had two chapters with an international focus, “Population” and “Warfare and International Organization,” as did the Merton and Nisbet text in its early editions. In 1976, however, Merton and Nisbet replaced their chapter on “Warfare and Disarmament” with a chapter on “Violence,” which focused on criminal behavior, and Julian never had a chapter on warfare. However, as the process of globalization won increasing public attention in the 1990s, this trend was slowly reversed. Not only did many of the texts begin including more comparative material, but some added a chapter on global inequality as Coleman and Cressey (1993) did in their fifth edition.

Three overall trends are therefore evident in the sociological study of social problems in North America. As just indicated, one trend has been toward greater inclusivity. First African Americans, then other ethnic minorities, then women, and finally gays and lesbians have slowly won inclusion in what was originally an exclusively white male vision of the world. A second trend has been the slow expansion of sociological horizons to recognize the importance of environmental concerns as well as to take a more global perspective.

A third trend, not as easily recognizable from our previous analysis, has been an underlying paradigmatic shift. To the extent that they used any explicit theoretical approach, the earlier texts were based on functionalist assumptions. Following Horton and Leslie (1955:27–32), they tended to argue that there were three theoretical approaches to social problems: social disorganization, personal deviance, and value conflict. The value-conflict approach should not, however, be confused with contemporary conflict theory inspired by Marxian thought. Its basic assumptions were clearly functionalist: Society needed value consensus, and “value conflict” was therefore a cause of social conflict (Fuller and Myers 1941). As sociology slowly adopted a more critical perspective, a few books with an exclusively conflict orientation were published, and for most of the other textbooks, this tripartite approach was recast. The social disorganization approach was expanded and renamed to include all functionalist theory. The personal deviance approach expanded to become the interactionist approach, which had less of a functionalist cast and included other social psychological phenomena in addition to deviance. Finally, the issue of value conflict was subsumed under the much broader and more critical umbrella of a conflict approach (for example, see Coleman and Cressey 1980).

Of the new trends that seem to be developing for the twenty-first century, an increasing globalization perspective is most important. There is now greater recognition that for the United States, globalization is creating new social problems or making old ones such as poverty and unemployment worse. The movement of U.S. factories overseas and outsourcing of all kinds of work have helped reduce wages for the bottom half of the American labor force (see Kerbo 2006b:chaps. 2 and 3). In addition to this, the antiglobalization movements of recent years, as well as research on the negative impact of globalization for developing countries (Kerbo 2006b:chap. 4), have brought greater attention to the subjects of world poverty, environmental pollution, and global migration for most books on social problems. With global inequality expected to continue increasing for many years into the twenty-first century, the trend will likely become more pronounced.

Paradigm Assumptions and Defining Social Problems

In his classic work The Sociological Imagination, C. Wright Mills (1959) argued we should distinguish between “‘the personal troubles of milieu’ and ‘the public issues of social structure’” (p. 8). For him, of course, it was “the public issues of social structure” that should be the focus of sociology when defining the nature of a social problem. Mills offered this example:

In these terms, consider unemployment. When, in a city of 100,000, only one man is unemployed, that is his personal trouble, and for its relief we properly look to the character of the man . . . But when in a nation of 50 million employees, 15 million men are unemployed, that is an issue . . . Both the correct statement of the problem and the range of possible solutions require us to consider the economic and political institutions of the society, and not merely the personal situation and character of a scatter of individuals. (P. 9)

Mills, obviously, offers a definition of social problems that focuses on the breakdown of basic social institutions that must take care of individuals and assure the survival of the society and its social institutions. His plea for a focus on social institutions seems straightforward and obvious; but he made such a plea because of the particular aspects of American culture that create a bias against this focus.

It has long been recognized that power (generally defined) and values interact to determine what comes to be seen as social problems. Those with wealth and influence in government and/or the mass media in modern societies are the ones most able to shape what the society comes to view as a social problem. But there are many forms of influence held by those below the top ranks in the society, making the study of social problems overlap with the study of social movements. Several years ago, for example, one of the basic American social problems textbooks employed the title Social Problems as Social Movements (Mauss 1975). As we will consider in the following, however, assuming that social movements help define social problems is also problematic because of the complex set of forces that make the emergence of social movements possible. But in addition to this, the recognition that social movements help define social problems continues to neglect the question of cultural assumptions and values that make one country, in one historical epic, view conditions differently for people in other times and places, as well as neglect the ability of those with wealth and power to shape the perspective on the causes and solutions to social problems once they have been defined as such.

Sociological analyses of sociology itself, a form of “deconstructionism” popular among professional sociologists during the 1960s and 1970s, long before the current fad in humanities, has shown that “paradigm assumptions” or “metatheoretical assumptions” shape all sociological theories at least to some degree (Gouldner 1970; Strasser 1976; Ritzer 2005). And while all scientific disciplines are influenced by these political, religious, or cultural assumptions (Kuhn 1970), these assumptions shape some fields within the social sciences to a greater extent than others. Theories and research on politically sensitive subjects such as crime and poverty, along with most subjects within the general area of social problems, are most influenced by these paradigm assumptions (Galliher and McCartney 1973; Useem 1976a, 1976b; Kerbo 1981).

To understand theories and research on social problems in the American society, it is first important to examine some of the general American values that shape views on these subjects. Various international opinion polls show the following: Americans have the highest scores on (1) individualism (Hofstede 1991), (2) beliefs in the existence of equality of opportunity, (3) beliefs that government cannot and should not reduce inequality or poverty (Ladd and Bowman 1998), and (4) beliefs that high levels of poverty and inequality are acceptable (Verba et al. 1987; Ladd and Bowman 1998). For the study of social problems in general, this has meant that American values suggest that individuals themselves are responsible for their problems rather than some aspect of the society or basic institutions. In contrast to the early appeals of C. Wright Mills noted in the foregoing, content analyses of articles on social problems published in American sociology journals through the second half of the twentieth century confirm that the focus tends to be on the characteristics of individuals rather than problems of society (Galliher and McCartney 1973; Useem 1976a, 1976b; Kerbo 1981, 2006a:254–59).

This research also shows that it is not simply the views of sociologists themselves that set the trend toward blaming the characteristics of individuals for social problems as much as the assumptions of funding agencies; most social science research is funded by government agencies and private foundations that are more interested in controlling social problems rather than changing aspects of the society that are often at the root of social problems (Kerbo 1981). Interviews with social scientists indicate that they are most often conducting research on questions that they know will get funding rather than on what they think are the most important sociological questions or subjects in which they are most interested (Useem 1976a, 1976b). What this research suggests is that while the rich and powerful may not always define what is seen as a social problem, they do have extensive influence over what we think are the causes and solutions to social problems. They help set the research agendas, what gets research attention, and what gets talked about in government circles and the mass media through this influence on the social sciences through research funding (see Domhoff 2006:77–132).

This is not to say, however, that the assumptions and interests of the less affluent and politically powerless do not shape what we come to define as social problems. For example, an abundance of research has shown that the civil rights movements of the 1960s, and especially the violent demonstrations and riots of that period, shaped the American society’s definition of poverty as a social problem (Piven and Cloward 1971, 1977). Indeed, several studies have shown strong correlations between urban riots of the 1960s and the expansion of welfare benefits to the poor (Betz 1974; Kelly and Snyder 1980; Isaac and Kelly 1981).

The tie between social movements and what comes to be defined as social problems is especially critical in the United States. Compared with the rest of the industrialized world, of course, a much smaller percentage of Americans tend to vote during national elections. But an even bigger contrast to other industrialized nations is the class makeup of those who do vote in the United States: Toward the upper-income levels, some 70–80 percent of Americans who are eligible to vote do so, compared with 30 percent or less for people with a below-average income. This is not the case with other industrial societies, where the voter turnout is about the same at every income level (Piven and Cloward 1988, 2000; Kerbo and Gonzalez 2003). This is to say, therefore, that when the less affluent and less politically powerful in the United States have influenced definitions of social problems, it has been comparatively more often done in the streets than through the political process.

The Causes of Social Movements and Their Impact on Definitions of Social Problems

Recognizing that social movements are important in identifying what a society comes to view as a social problem forces us to ask how social movements themselves emerge. It is not our intent to review all the literature on the causes of social movements, but a brief summary of this literature is essential when considering how social problems have been defined in the United States.

For many years the study of social movements was dominated by theories based on some form of “deprivation” argument. In other words, social movements were seen to emerge and attract widespread membership because participants felt a sense of anger or outrage at their condition. Recognizing that long-standing deprivations do not always or even often spark widespread social movement activity (such as decades or centuries of discrimination and exploitation of a minority group by the majority), most deprivation theories of social movements attempted to explain how some type of change leads to a redefinition of the situation. The most popular of this type of theory has been called “relative deprivation theory” or “J-curve theory” (Davies 1962, 1969; Gurr 1970). During the early 1800s, Tocqueville (1955) recognized that, ironically, social movements and revolutions tend to emerge when conditions are actually improving. More recent refinements of “relative deprivation theory” distinguish between what is called “value expectations” and “value capabilities.” When value capabilities are low (such as high levels of poverty) and have been so for a long period of time, people come to accept their situation or assume improvements are unlikely or impossible. People in deprived situations are often, even likely, to be persuaded that they themselves are responsible for their condition and thus have no one else to blame (Piven and Cloward 1971; Gans 1972). This is to say that low-value capabilities are usually associated with lowvalue expectations over long periods of time. Thus, to understand the emergence of social movements, relative deprivation theories suggest the need to understand how value capabilities and value expectations move apart.

Obviously, the gap between the two can develop because value capabilities worsen (such as a big jump in unemployment of the working class), thus creating a gap between previous expectations and newly lowered capabilities. Faced with a sudden crisis, people seldom assume their situation is hopeless or that they deserve their worsening situation. However, as Tocqueville (1955) was first to recognize, social movements and revolutions actually seem to occur when long-standing conditions of deprivation are actually improving. Refinement of relative deprivation–type theories has come to suggest that improving conditions quickly raise levels of expectation, but improving conditions seldom occur without fluctuation, meaning that a sudden downturn in improving conditions creates the gap between value capabilities and value expectations. It is anger or fear that improvements finally achieved will be short lived that motivate more and more people to join a social movement.

While research has shown that some form of “relative deprivation” seems to have preceded many social movements, others have noted that this is not always the case— nor is anger or a sense of deprivation in and of itself usually sufficient to make a social movement. In recent years, what is generally referred to as “resource mobilization theory” has become much more popular among sociologists attempting to explain the development and spread of social movements (for original development of the perspective, see McCarthy and Zald 1977). In its basics, resource mobilization theory is a form of conflict theory focused on the balance of power between authorities (or the more powerful in a society) and those with possible grievances. Reduced power of authorities, increased power among those with a grievance, or both can lead to a strong social movement.

The concept of “resources” in resource mobilization theory refers to any value or condition that can be used to the advantage of a group. Obviously important are such things as money, publicity, arms, and the ability to interact with and organize larger numbers of people for the cause. In one of the first studies using resource mobilization theory, for example, Paige (1975) was able to show that certain kinds of crops and certain types of agricultural organization (such as wet rice agriculture with absentee landowners) are more likely associated with peasant revolts and revolutions because of the ability peasants have to interact freely, share common grievances, and be organized to oppose landowners. Likewise, the loss of legitimacy and the ability to punish opponents or hide information are conditions that reduce the power and resources of authorities. Ted Gurr (1970) has produced a long list of possible resources that includes things such as terrain (ability to hide or ability of authorities to uncover rebels), food supplies, and outside allies that can influence the power and size of social movements.

Perhaps more than any other social movement in recent American history, the new resource mobilization theory of social movements led to a reanalysis of the civil rights movement. Because of this extensive reanalysis of the causes of the civil rights movement, it is worth considering in more detail here how a particular social problem, racism and discrimination, came to be widely defined as a social problem in the second half of the twentieth century.

Civil Rights Movement

Considering the importance of the civil rights movement in the United States for defining racism, discrimination, and poverty as social problems, it is useful to consider how this social movement emerged and to consider the value of the social movement theories described in the foregoing.

Relative deprivation theory has some success in explaining why the more violent stage of the civil rights movement emerged in the mid-1960s. Sociologists using this perspective argue that the more violent stage of the civil rights movement was in response to a white “backlash” that resulted in some setbacks to the earlier achievements of the civil rights movement from the 1950s (Davies 1969). However, relative deprivation theory has difficulty in explaining why the civil rights movement suddenly appeared in the early 1950s, while so many other attempted social movements by black Americans failed in earlier American history. In recent years, research has shown resource mobilization theory to be a powerful tool in understanding why the civil rights movement became widespread and powerful when and where it did so (McAdam 1982).

In summary, the civil rights movement benefited from several changes that occurred in the American society after World War II. Among the most important changes was agricultural mechanization, which moved a majority of black Americans from rural areas and agricultural jobs into large cities all over the United States. Larger concentrations of black Americans in urban areas provided the ability to reach and organize far greater numbers of social movement participants than before. A key to organizational ability was also found in the huge churches dominated by black Americans in large cities in the southern United States. These black churches made possible organization within the denomination and across churches all over the South. At the same time, these large black churches provided support for social movement participants and their families when they were jailed or injured in social movement activities.

Among other new resources in the 1950s were more mass-media exposure to actions against black Americans and social movement activities that had remained relatively hidden in small cities and rural areas throughout the South in previous generations. But related to this was political change, as the Democratic Party lost its previously solid majority in the South. To counter this loss, the Democratic Party decided to “go for” new urban concentrations of potential black votes in the late 1950s. It was politicalization of black grievances in the presidential election of 1960 that gave black social movement activists more resources of many kinds and John F. Kennedy the presidency in one of the closest elections when newly organized black voters gave him overwhelming support.

Movements of Affluence

The foregoing analysis of social movements and their causes as instrumental in defining what comes to be seen as a social problem, however, should not be seen as reinforcing the common assumption that social movements are primarily by and for the poor and oppressed. We must recognize the distinction between what has been called “movements of crisis” and “movements of affluence” (Kerbo 1982). Most movements of crisis are made up of people who face critical problems such as poverty, discrimination, or some other deprivation. Most movements of affluence, on the other hand, involve people who are relatively comfortable, if not affluent, and have the luxury of devoting their attention and energy on “moral issues.” Current social movements in the United States that are usually pushed by people on the political right (such as the anti-abortion movement) as well as the political left (such as the environmental movement and antiglobalization) must be included among these movements of affluence, which focus on moral issues or issues that are not of immediate harm to individual social movement participants.

Solutions to Social Problems

We can conclude with an examination of what are considered “solutions” to social problems. While the possible solutions to social problems are seldom recognized, they are equally, if not more, shaped by power and influence in a society. Over the last four decades in the United States, the extent and seriousness of many, if not most, social problems have remained relatively unchanged. For example, while violent crime and property crime have dropped in recent years, violent crime especially remains at high levels compared with other industrial nations. Drug use has gone up and down within only a narrow range. Teenage pregnancy has dropped only slightly. Poverty rates have ranged between 11 and 15 percent of the American population in the last 40 years, among the highest in the industrialized world. These continuing high levels of social problems in the United States might suggest that relatively little has been learned about the subject in the last half century of sociological research. The reality, however, is quite different. Even more complex than definitions of social problems is finding solutions that do not adversely affect groups with more political and/or economic power or impinge on important values of the dominant group in the society. Consideration of possible solutions to poverty and inequality will be useful in demonstrating the point.

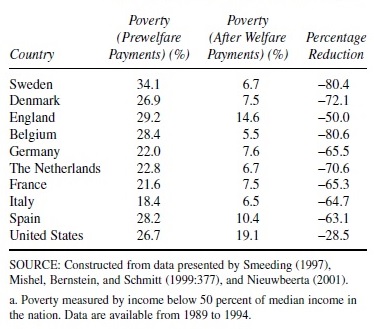

In most of the original European Union countries, poverty rates are substantially below the American rates. Using the purchasing power parity (PPP) method of estimating currency values, and using the poverty line established by the U.S. Census Bureau (roughly $11 per day per person), during the late 1990s (the most recent years we have data for several European countries) the U.S. poverty rate was over 13 percent, compared with about 7 percent in Germany and the Netherlands and around 4 percent in Scandinavian countries (Smeeding, Rainwater, and Burtless 2001:51). But while the American poverty rates are comparatively high, unemployment at around 4 to 5 percent in the same time period was low compared to over 10 percent unemployment in most original EU countries. There are two interacting explanations for this: First, in contrast to the United States, European labor unions are strong enough to force government action to keep poverty low even at the expense of higher unemployment rates (Esping-Anderson 1990; Thelen 1991; Goodin et al. 1999; Kerbo and Gonzalez 2003). Second, opinion polls indicate that Europeans are more concerned than are Americans about high inequality and poverty among their citizens and believe that governments have the responsibility to reduce poverty and inequality (Verba et al. 1987; Ladd and Bowman 1998). These two explanations are also behind the figures we see in Table 1. Without government action, poverty rates in Europe would be about the same or even higher than in the United States. But government interventions in Europe reduce poverty rates by 50 to 80 percent, compared with only a 28 percent reduction in the United States. Not surprisingly, the EU country with the weakest unions today and values closest to the United States, the United Kingdom, has the lowest rate of reducing poverty through government action in Europe and, using the PPP $11 per day poverty line, a poverty rate of 15.7 percent compared with 13.6 percent in the same time period in the United States (Smeeding et al. 2001:51).

The contrast between Germany and the United States is most clear. The influence of the American corporate elite, in the context of American values stressing individualism, has led the American public to generally accept the argument that the government should not be allowed to raise taxes, increase unemployment benefits, or raise minimum-wage laws to reduce poverty. Rather, the argument is that corporations and the rich should be left alone as much as possible to generate wealth that will then expand job opportunities that will reduce poverty among Americans. (For a broader discussion of this German vs. American contrast, see Kerbo and Strasser 2000, Kerbo 2006b:chap. 3.) In Germany, by contrast, the power of labor unions and labor laws already instituted with labor union pressure will not allow such government inaction as a presumed solution to the problem of poverty.

Another example can be briefly considered. Several studies indicate that high employment rates are instrumental in producing crime (Blau and Blau 1982; Williams 1984), which at least in part helps explain the lower crime rates in the United States from the early 1990s to the present. Thus, a guaranteed job after release from prison would significantly reduce the rate of recidivism. But since the 1930s, American politicians have not been willing to create employment through government programs in times of high unemployment or guarantee jobs to felons released from prison. The American corporate elite have been successful in blocking such government job guarantees or jobs created by government, even though it is clear this would be one viable solution to high rates of crime.

There are many other examples: Decriminalizing drugs would likely help reduce both property crime and drug addiction as it has in some European countries, and more sex education and freer access to condoms would help reduce teenage pregnancy rates, which are far higher in the United States than in Europe. But as with definitions of what is or is not a social problem, power and influence in combination with particular societal value orientations that can be exploited by those with power are also involved with what come to be viewed as accepted solutions to social problems.

Bibliography:

- Betz, Michael. 1974. “Riots and Welfare: Are they Related?” Social Problems 21:345–55.

- Blau, Judith and Peter Blau. 1982. “The Cost of Inequality: Metropolitan Structure and Violent Crime.” American Sociological Review 47:114–29.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1971. “Social Problems as Collective Behavior.” Social Problems 18:298–306.

- Coleman, James William and Donald R. Cressey. 1980. Social Problems. New York: Harper & Row.

- Coleman, James William and Donald R. Cressey. 1993. Social Problems. 5th ed. New York: HarperCollins.

- Davies, James C. 1962. “Toward a Theory of Revolution.” American Journal of Sociology 27:5–19.

- Davies, James C. 1969. “The J-Curve of Rising and Declining Satisfactions as a Cause of Some Great Revolutions and a Contained Rebellion.” Pp. 671–710 in Violence in America, edited by H. D. Graham and T. R. Gurr. New York: Signet Books.

- Domhoff, G. William. 2006. Who Rules America? New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Esping-Anderson, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fuller, Richard C. and Richard R. Myers. 1941. “The Natural History of a Social Problem.” American Sociological Review 6:320–28.

- Gans, Herbert. 1972. “Positive Functions of Poverty.” American Journal of Sociology 78:275–89.

- Galliher, John and James McCartney. 1973. “The Influence of Funding Agencies on Juvenile Delinquency Research.” Social Problems 21:77–90.

- Gallup, George H. 2004. The Gallup Report. Retrieved June 28, 2004 (http://www.gallup.com).

- Garraty, John. 1978. Unemployment in History: Economic Thought and Public Policy. New York: Harper & Row.

- George, Henry. [1883] 1939. Social Problems. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

- Goodin, R. E., B. Headey, R. Muffels, and H. Dirven. 1999. The Real Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Gouldner, Alvin. 1970. The Coming Crisis in Western Sociology. New York: Basic Books.

- Gurr, Ted. 1970. Why Men Rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hofstader, Richard. 1955. The Age of Reform: From Bryan to FDR. New York: Knopf.

- Hofstede, Geert. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Horton, Paul B. and Gerald R. Leslie. 1955. The Sociology of Social Problems. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Isaac, Larry and William Kelly. 1981. “Racial Insurgency, the State, and Welfare Expansion: Local and National Level Evidence from the Postwar United States.” American Journal of Sociology 86:1348–86.

- Julian, Joseph. 1973. Social Problems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Julian, Joseph. 1977. Social Problems. 2d ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Kelley, William and David Snyder. 1980. “Racial Violence and Socioeconomic Changes among Blacks in the United States.” Social Forces 58:739–60.

- Kerbo, Harold. 1981. “Characteristics of the Poor: A Continuing Focus in Social Research.” Sociology and Social Research 65:323–31.

- Kerbo, Harold R. 1982. “Movements of ‘Crisis’ and Movements of ‘Affluence’: A Critique of Deprivation and Resource Mobilization Theories of Social Movements.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 26:645–63.

- Kerbo, Harold R. 2006a. Social Stratification and Inequality: Class Conflict in Historical, Comparative, and Global Perspective. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kerbo, Harold R. 2006b. World Poverty: Global Inequality and the Modern World System. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kerbo, Harold and Juan Gonzalez. 2003. “Class and Nonvoting in Comparative Perspective: Possible Causes and Consequences for the United States.” Research in Political Sociology 12:177–98.

- Kerbo, Harold and Hermann Strasser. 2000. Modern Germany. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kuhn, Thomas. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2d ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Ladd, Everett Carll and Karlyn H. Bowman. 1998. Attitudes toward Economic Inequality. Washington, DC: AEI Press.

- Mauss, Armand L. 1975. Social Problems as Social Movements. New York: Lippincott.

- McCarthy, John D. and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology. 82:1212–41.

- McAdam, Doug. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency: 1930–1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McLellan, David. 1973. Karl Marx: His Life and Thought. New York: Harper & Row.

- Mead, George H. 1899. “The Working Hypothesis of Social Reform.” American Journal of Sociology 5:404–12.

- Merton, Robert K. and Robert Nisbet. 1971. Social Problems. 3d ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Merton, Robert K. and Robert Nisbet. 1976. Social Problems. 4th ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nieuwbeerta, Paul. 2001. “The Democratic Class Struggle in Postwar Societies: Traditional Class Voting in Twenty Countries, 1945–1990.” Pp. 121–36 in The Breakdown of Class Politics: A Debate on Post-Industrial Stratification, edited by T. N. Clark and S. M. Lipset. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- Paige, Jeffrey. 1975. Agrarian Revolution. New York: Free Press. Parsons, Talcott. 1937. The Structure of Social Action. New York: Free Press.

- Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. 1971. Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare. New York: Basic Books.

- Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. 1977. Poor Peoples’ Movements: Why They Succeed, Why They Fail. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. 1988. Why Americans Don’t Vote. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. 2000. Why Americans Still Don’t Vote: And Why Politicians Want It That Way. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Ritzer, George. 2005. Sociological Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Schwendinger, Herman and Julia R Schwendinger. 1974. The Sociologists of the Chair: A Radical Analysis of the Formative Years of North American Sociology, 1883–1922. New York: Basic Books.

- Smeeding, Timothy M., Lee Rainwater, and Gary Burtless. 2001. “United States Poverty in a Cross-National Context.” Pp. 162–92 in Understanding Poverty, edited by S. H. Danziger and R. H. Haveman. New York: Russell Sage.

- Spector, Malcolm and John I. Kitsuse. 1973. “Social Problems: A Reformation.” Social Problems 21:145–59.

- Strasser, Hermann. 1976. The Normative Structure of Sociology: Conservative and Emancipatory Themes in Social Thought. London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Thelen, Kathleen A. 1991. Union of Parts: Labor Politics in Postwar Germany. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de. 1955. The Old Regime and the French Revolution. New York: Doubleday.

- Useem, Michael. 1976a. “State Production of Social Knowledge: Patterns in Government Financing of Academic Social Research.” American Sociological Review 41:613–29.

- Useem, Michael. 1976b. “Government Influence on the Social Science Paradigm.” Sociological Quarterly 17:146–61.

- Verba, Sidney, Steven Kelman, Gary Orren, Ichiro Miyake, Joji Watanuki, Ikuo Kabashima et al. 1987. Elites and the Idea of Equality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Williams, Kirk. 1984. “Economic Sources of Homicide: Reestimating the Effects of Poverty and Inequality.” American Sociological Review 49:283–89.