Sample Life Expectancy And Adult Mortality Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

This research paper is concerned with trends, sex differences, and socioeconomic differences in life expectancy since 1950. The focus is on the so-called established marketeconomy (EME) countries, including Western Europe, North America, Oceania, and Japan.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Trends In Life Expectancy In Main Groups Of Industrialized Countries

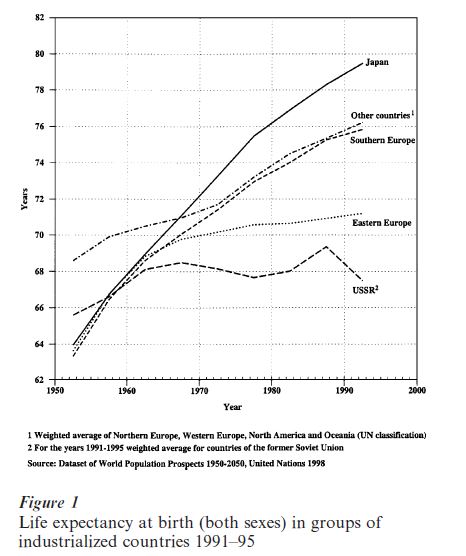

There were some marked differences in life expectancy among groups of the (currently) industrialized countries in the early 1950s. Average life expectancy in the less developed countries (Southern and Eastern Europe, and Japan) was more than four years lower than in the more developed countries in Western Europe, North America, and Oceania (Fig. 1). In the 1950s and 1960s the differences diminished, as life expectancy increased more rapidly in the high mortality countries.

The period from 1945 to 1970 has been called the ‘era of antibiotics’ (Kannisto et al. 1999). During this period antibiotics proved effective against a wide range of diseases and infections. The increase in life expectancy was therefore fastest in the less developed areas, where infectious diseases were still common and infant and child mortality high (e.g., Southern Europe and Japan).

This convergence of life expectancies proved short- lived, however; the differences between the main groups of countries started to increase during the late 1960s. By 1980 the differences among the regions were far greater than in 1950. By the early 1990s, life expectancy in Japan was more than 12 years higher than in the countries of the former Soviet Union. This was due to the exceptionally rapid increase in life expectancy in Japan and the stagnation and even decline of life expectancy in the (former) Soviet Union. Life expectancy also increased in the market-economy countries other than Japan, but less rapidly so. In the (former) socialist countries of Eastern Europe the increase in life expectancy was slow during the 1970s and 1980s, and these countries lagged far behind the other industrialized countries in the 1990s.

Because infant and child mortality was low as early as in the 1970s in the EME countries, decline in adult mortality became a more important and later the dominant cause of the increase in life expectancy in these countries. For example, in England and Wales about one-third of the increase in life expectancy was attributable to the decline in mortality in the age group 0–14 years from 1970 to 1980, but less than one-tenth from 1980 to 1990. More than half of the increase in the 1980s was due to the decline in mortality among persons over 65 years of age (Mesle 1996).

In populations with a low life expectancy, infant and child mortality have a strong influence on the level of life expectancy at birth. In the EME countries discussed here, this is no longer the case: death rates in the youngest age groups have dropped to such a low level that they have a minor influence on trends differentials in life expectancy at birth. They are determined almost entirely by mortality in adult ages.

The increase in the importance of adult age groups has been mainly due to the decline of mortality from cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and other diseases of the circulatory system). The decline in cardiovascular disease mortality was slow in the 1950s and 1960s, and in many countries male mortality from these diseases actually increased. The decrease in all-cause mortality in older age groups was modest during this period. Around 1970 mortality among the elderly began to decline in most Western countries as never before in recorded history, and gains in survival were observed even at the highest ages (Kannisto et al. 1999).

An analysis of the decline in adult mortality in the United States led Olshansky and Ault (1986) to conclude that the United States had entered a ‘fourth stage in epidemiologic transition.’ This new stage is characterized by rapid mortality declines in older people resulting from a postponement of the age at which degenerative diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases, tend to kill. They refer to this new stage as the Age of Delayed Degenerative Diseases.

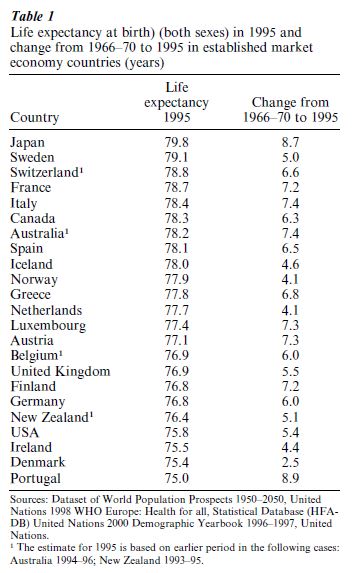

Life expectancy increased in all EME countries from the late 1960s to the 1990s. The increase was greatest in Portugal (see Table 1), which had lagged far behind the other countries in the 1960s. Despite this rapid increase Portugal still had the lowest life expectancy in the EME group in 1995. In general, the increase in life expectancy was below average in countries with a high life expectancy in the 1960s (e.g., Norway, Sweden, and The Netherlands).

Denmark is a special case. Danish life expectancy was relatively high in the 1960s, but since then progress has been clearly slower than in the other EME countries. In 1995, life expectancy in Denmark was second lowest after Portugal in the EME group. Japan is another special case. By the late 1960s life expectancy had reached the average level of advanced industrialized countries, by the mid-1990s Japan had the highest life expectancy in the world at 79.8 years.

Cross-national differences in life expectancy among developed countries are not related to standard of living or the level of gross national product (Wilkinson 1996). For example, rich countries such as the US and Germany have lower life expectancies than Greece and Spain. No systematic analyses have been done of the causes of cross-national differences in life expectancy, but several studies have addressed specific questions. These studies are based on the analysis of differences in mortality by cause of death and in the prevalence of known risk factors for specific causes of death. For example, a partial explanation for the high life expectancy in Japan is the low-fat Japanese diet, which contributes to the very low mortality from heart disease. The low mortality from coronary heart disease in southern Europe has also been explained by reference to dietary factors, more specifically to the so-called Mediterranean diet which includes olive oil, fresh fruits, and relatively little animal fat. The exceptionally slow recent increase in life expectancy in Denmark seems to be related to the high prevalence of smoking- and alcohol-related diseases.

2. Sex Differentials In Life Expectancy

Women live longer than men in all industrialized countries, but the difference between female and male life expectancy varies. At the beginning of the twentieth century the differential in several countries (Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy, and Japan) was small (United Nations Secretariat 1988). The differential was largest (3.9 years) in England and Wales. From the 1930s to the 1970s, increases in the sex differential in life expectancy were a universal feature because women benefited more than men from the decline of mortality.

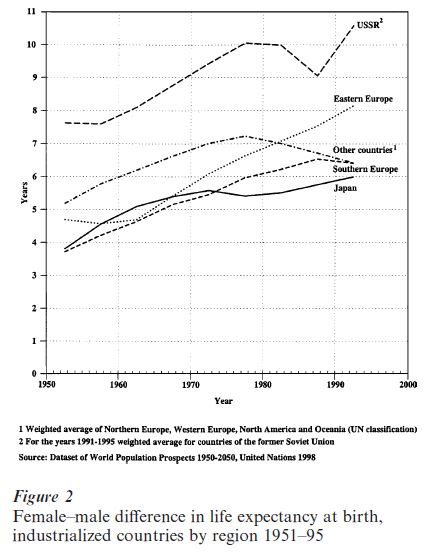

Figure 2 describes the development of the sex differential in life expectancy for groups of industrialized countries from 1950 to 1995. By the 1950s the average differential in North-Western Europe and North America exceeded five years. The differential was smaller in the less industrialized regions (Eastern and Southern Europe and Japan). In the relatively unindustrialized Soviet Union, however, the difference was clearly largest, almost eight years.

Until the late 1970s the gap between female and male life expectancy grew almost constantly in all regions. This growth was most rapid in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In North-Western Europe, North America, and Oceania the gap started to diminish in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and in Southern Europe a decade later. In Eastern Europe the difference continued to grow rapidly. In the Soviet Union there was a curious temporary decrease from 1976–9 to 1986–9. This was associated with the increase in life expectancy brought about by President Gorbatchev’s antialcohol campaign, which had a greater impact on male than female mortality.

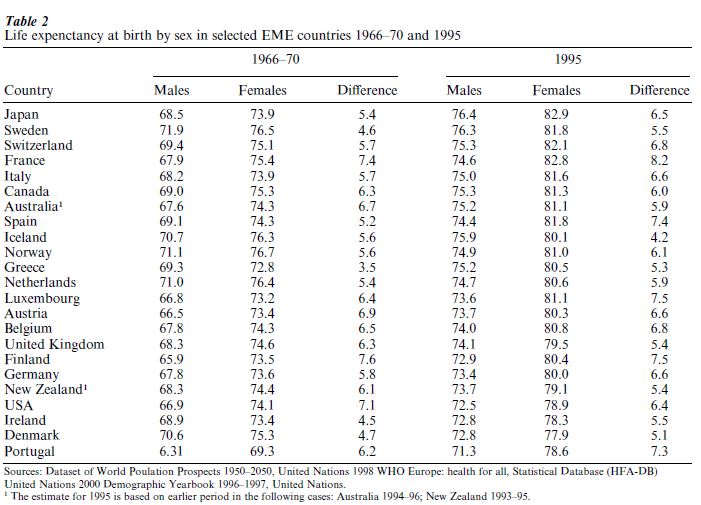

Both the sizes of and the trends in the sex difference in life expectancy have varied markedly between countries. For example, France and the United States had approximately the same difference in 1970. In the United States the difference was relatively constant until 1979, and then decreased by more than two years. In France, the sex difference continued to increase into the second half of the 1980s, and diminished only slightly in the early 1990s. In the United Kingdom the decline started earlier than in other countries. In Italy the first signs of decrease did not appear until the 1990s. In 1995 France, Finland, Portugal, and Luxembourg had differentials of more than seven years, whereas the differential was less than five and half years in Sweden, Ireland, Greece, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark (Table 2).

The lower life expectancy of men in developed countries is due to higher male death rates in all age groups and for most causes of death. An analysis of the contribution of broad groups of causes of death in 26 developed countries in the early 1980s showed that the higher mortality of men from diseases of the circulatory system, particularly from ischaemic heart disease, made the largest contribution to the differential in life expectancy. Diseases of the circulatory system accounted on average for 40 percent of the total sex differential. Neoplasms (cancer) accounted for 18 percent, more than half of which was due to lung cancer. External causes (accidents, suicide, and violence) accounted for 19 percent. The contributions of these causes of death varied between different countries, however, widely (United Nations Secretariat 1988).

The causes of the higher mortality of men from circulatory diseases, cancer, and other causes of death are only partly known. The size of the sex difference in mortality from each specific cause of death is influenced by a wide variety of environmental and genetic factors, and the contribution of particular factors varies greatly depending on socioeconomic and cultural conditions (Waldron 1986). For example, when maternal mortality was high, that reduced the female–male difference in life expectancy. The decline in maternal mortality has contributed to the increase in the life expectancy gap during this century, but the present very low rate of maternal mortality has hardly any effect on sex differences in life expectancy.

There is evidence to support the hypothesis that female sex hormones reduce women’s risk of ischaemic heart disease, in part due to their favorable effects on serum lipids, while men’s higher testosterone levels have unfavorable effects on serum lipids. The higher male mortality from ischaemic heart disease is therefore probably due in part to genetic differences between men and women. In countries (e.g., Finland/or the United Kingdom) where mortality from ischaemic heart disease is high, these genetic differences contribute more to the overall sex difference in life expectancy than in countries with low mortality from ischaemic heart disease (e.g., Japan or Greece). Waldron (1995) suggests that changes in diet, particularly in the consumption of animal fat, have had greater effects on male than female ischaemic heart disease mortality. It is likely that changes in diet have contributed both to the earlier increase and to the more recent decrease in sex differentials in life expectancy.

A major well-established cause of the increase in the sex differential since the 1930s is that men adopted cigarette smoking much earlier than women. Male cigarette smoking has contributed to the increase in male excess mortality from cardiovascular diseases (particularly ischaemic heart disease), cancer (particularly lung cancer), and diseases of the respiratory system. In her review of 12 studies, most of which were based on samples drawn from the US population from the 1950s to the 1980s, Waldron (1986) estimated that approximately half of the sex difference in adult allcause mortality was attributable to smoking.

A study on the contribution of smoking to sex differences in life expectancies in four Nordic countries and The Netherlands in 1970–89 (Valkonen and van Poppel 1997) estimated that, on average, more than 40 percent of the average sex difference in these countries in 1970–4 was attributable to more prevalent smoking among men. By 1985–9 the contribution of smoking dropped to approximately 30 percent of the total difference. In all five countries the loss of life expectancy due to cigarette smoking increased among women. In Denmark the loss was 1.6 years in 1985–9, but less than six months in the other countries.

Alcohol use is another important factor contributing to the lower life expectancy of men. There are no cross-national studies, but the contribution of this factor obviously increases in line with rising alcohol related mortality and growing sex differences in drinking men and women. Makela (1998) estimated that at least one-fifth of the sex difference in life expectancy in Finland in 1987–95 was attributable to the higher male mortality from alcohol-related causes.

Death rates for accidents, suicide, and other violent causes have been found to be higher for males than females in almost all available historical and international data, although the magnitude of the male excess varies. This difference is partly due to the heavier alcohol consumption among men. Social norms and expectations that favor more aggressive and risk-taking behavior among men also play a role. There are also hypotheses that there is a genetic basis for the differences in accident-prone and violent behavior.

There are other factors apart from those discussed above that affect or may affect sex differences in mortality. These include differences in the use of health services, in the prognosis or survival rates for various diseases, economic Activity, vulnerability to disruption of social relationships including marriage, etc. However, in the light of the evidence available, these are less significant than behavioral factors.

3. Socioeconomic Differences In Mortality

Differences in mortality between subpopulations within countries have been studied by several variables, such as region of residence, rural–urban residence, marital status, and socioeconomic position. These intracountry differences are sometimes as large or larger than cross-country differences, and they are extremely important from the point of view of health and social policy planning. Differences between socioeconomic groups are particularly important because they tend to be greater than other differences between subpopulations.

Figures on mortality by socioeconomic category are not normally presented in regular statistics. The data for England and Wales published by the Registrar General (later the Office of National Statistics) since 1851 in the so-called Decennial Supplements provide the only long-term series of mortality statistics by occupational and social class (OPCS 1978, Drever and Whitehead 1997). Most of the knowledge about socioeconomic mortality differences is based on specific studies, the results and reliability of which depend on several factors, such as the source and coverage of data, the socioeconomic indicators used, and the way in which mortality and size of mortality differentials are measured.

Despite data problems, study after study in different populations have shown that persons in lower socioeconomic positions die on average at a younger age than those in higher positions. For example, in England and Wales the estimated gap in life expectancy at birth between men in Classes I II (professional, managerial, and technical occupations) and men in Classes IV V (partly skilled and skilled workers) was five years in 1987–91; for women the differential was three years (Drever and Whitehead 1997).

Cross-national variations in the extent of socio-economic differences in mortality by level of education and/or occupational class have been studied in a large-scale project covering 11 Western European countries, the United States, and three former socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe (Kunst 1997). The main part of the data covered middle-aged men from ca. 1980 to ca. 1990.

In all countries the mortality rate of manual classes was higher than that of nonmanual classes. The relative excess mortality of the manual classes was remarkably similar for most Western European countries and the United States. France and Finland had somewhat greater mortality differences than other Western European countries but smaller than Hungary. The results did not support the view that inequalities in health are smaller in countries where social, economic, and health care policies are to a greater extent influenced by egalitarian principles such as Sweden and Norway (Mackenbach et al. 1997).

It has been observed that male mortality in manual classes is higher than in nonmanual classes for nearly all causes of death. Relative differences are particularly large and systematic in mortality from respiratory diseases and from accidents and violence. The comparative study by Mackenbach and colleagues showed one interesting exception: hardly any class differences were found in France, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain in mortality from ischaemic heart disease. In Portugal mortality rates were higher in the nonmanual than manual classes. On the other hand, socioeconomic gradients in mortality from causes other than ischaemic heart disease were steeper in Southern than in Northern European countries and the United States.

Discussing the reasons for the small differences in mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Southern Europe, Kunst (1997) suggests that this is probably related to the low national levels of ischaemic heart disease. In these countries men seem to be protected against ischaemic heart disease by their frequent consumption of fresh vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oil. Diet may have protected lower socioeconomic groups in particular.

In all countries for which reliable data are available, socioeconomic differences in mortality are smaller among women than men, but there have been no comparative analyses to explore the causes of this phenomenon.

Koskinen and Martelin (1994) found that the smaller socioeconomic differences among women in Finland were mainly due to the different distribution of causes of death among women and men. Causes of death with small (most cancers) or reversed (breast cancer) socioeconomic differentials were more common among women than men. Causes with large differentials (accidents and violence, lung cancer, coronary heart disease), on the other hand, were more common among men.

Data on life expectancy by occupational class for England and Wales as well as for Finland show a clear widening in the gap between manual and nonmanual classes both among men and women since the 1970s (Drever and Whitehead 1997, Valkonen 1999). Results on changes in life expectancy by socioeconomic variables are not available for other countries, but other types of data show that at least relative socioeconomic differences in mortality among men increased in the 1980s in all countries for which some data are available (e.g., the United States, the Nordic countries, and France).

It has been suggested that these trends are a consequence of the general increase in social inequality and income differentials. Although this may be true in some cases, it cannot be generalized to all countries, because mortality differences have increased both in countries where income differentials have increased (e.g., Britain) and in countries where they have decreased (e.g., Finland).

The main common factor contributing to the increase in socioeconomic mortality differentials in several countries is the decline in mortality from cardiovascular diseases, which has been more rapid in the nonmanual and better educated classes than in other population groups. The upper classes have benefited more from the decline in cardiovascular mortality, probably because they have been quicker to adopt recommended health behaviors (concerning diet, smoking, physical Activity, etc.), and because they may have had better access to new medical treatments, such as coronary artery bypass grafting and angioplasty.

Causes of socioeconomic differences in mortality have been discussed extensively and many different hypotheses have been offered. Some hypotheses are based on the causal effect of socioeconomic position on mortality. According to these hypotheses differences between classes in material working and living conditions, in health-related behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, diet) or in the prevalence of psychosocial stressors cause differences in mortality. Another set of hypotheses is based on assumptions of direct or indirect selection of persons into social classes. According to the direct selection hypothesis, the higher mortality of lower classes is due at least in part to the negative effect of poor health on socioeconomic position. The indirect selection hypothesis assumes that certain characteristics of individuals (e.g., social background, intelligence, or psychosocial traits) affect both their socioeconomic position and their health and mortality.

Bibliography:

- Caselli G, Lopez A D (eds.) 1996 Health and Mortality among Elderly Populations. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Daugherty H G, Kammeyer K C W 1995 An Introduction to Population. The Guilford Press, New York, London

- Department of International Economic and Social Affairs 1982 Levels and Trends of Mortality since 1950. ST/ESA/SER.A 74, United Nations, New York

- Drever F, Whitehead M (eds.) 1997 Health Inequalities. Decennial Supplement. Office of National Statistics, Series DS No. 15, The Stationery Office, London

- Kannisto V, Turpeinen O, Nieminen M 1999 Finnish life tables since 1751. Demographic Research 1: 1–26, http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol1/1

- Koskinen S, Martelin T 1994 Why are socioeconomic mortality differences smaller among women than among men? Social Science Medicine 38: 1385–96

- Kunst A 1997 Thesis Erasmus University Rotterdam, CipGegevens Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, The Netherlands

- Lopez A, Caselli G, Valkonen T (eds.) 1995 Adult Mortality in Developed Countries. From Description to Explanation. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Mackenbach J P, Kunst A E, Cavelaars A E J M, Groenhof F, Geurts J J M The EU 1997 Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health 1997 Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The Lancet 349: 1655–9

- Makela P 1998 Alcohol-related mortality by age and sex and its impact on life expectancy. European Journal of Public Health 8: 43–51

- Mesle F 1996 Mortality in Eastern and Western Europe: A widening gap. In: Coleman D (ed.) Europe’s Population in the 1990s. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Office of Population Censuses and Surveys 1978 Occupational Mortality. The Registrar General’s Decennial Supplement for England and Wales 1970–72 . Series DS no. 1, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

- Olshansky S J, Ault A B 1986 The fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition: The age of delayed degenerative diseases. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 64: 355–91

- Trovato F, Lalu N M 1996 Causes of death responsible for the changing sex differentials in life expectancy between 1970 and 1990 in thirty industrialized nations. Canadian Studies in Population 23: 99–126

- Uemura K, Pisa Z 1988 Trends in cardiovascular disease mortality in industrialized countries since 1950. World Health Statistics Quarterly 41: 155–78

- United Nations 1998 World Population Prospects. The 1996 Revision. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. ST/ESA/SER.A/167, United Nations, New York

- United Nations Secretariat 1988 Sex differentials in life expectancy and mortality in developed countries: an analysis by age groups and causes of death from recent and historical data. Population Bulletin of the United Nations, Department of International Economic and Social Affairs, No. 25-1988, ST/ESA/SER.N /25, United Nations, New York

- Valkonen T 1999 The widening differentials in adult mortality by socio-economic status and their causes. In: Chamie J, Cliquet R L (eds.) Health and Mortality. Issues of Global Concern. Proceedings of the symposium on Health and Mortality, Brussels, 19–22 November 1997. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Secretariat and Population and Family Study Centre, Flemish Scientific Institute, Leuven, Belgium

- Valkonen T, van Poppel F 1997 The contribution of smoking to sex differences in life expectancy. Four Nordic countries and The Netherlands 1970–1989. European Journal of Public Health 7: 302–10

- Vallin J, D’Souza S, Palloni A (eds.) 1990 Measurement and Analysis of Mortality. New Approaches. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Waldron I 1985 What do we know about causes of sex differences in mortality? A review of the literature. Population Bulletin of the United Nations No. 18-1985, ST/ESA/SER.N/18, United Nations, New York

- Waldron I 1986 The contribution of smoking to sex differences in mortality. Public Health Reports 101: 163–73

- Waldron I 1995 Contributions of biological and behavioral factors to changing sex differences in ischaemic heart disease mortality. In: Lopez A, Caselli G, Valkonen T (eds.) Adult Mortality in De eloped Countries. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Wilkinson R G 1996 Unhealthy Societies. The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge, London and New York