Sample Core Sociology Databases Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

A database consists of one or more data sets, such as a sequence of decennial censuses. Databases reach core status for several reasons. One is sheer frequency of use. In the USA, the General Social Survey (GSS), a series of cross-sectional surveys beginning in 1972, is used by more than 200,000 students a year and by hundreds of researchers. The data are freely available to anyone via the Internet (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/GSS99/, (which gets more than two million hits a year) and are well documented and easily accessible. Other databases become influential because they yield fundamental results and serve as a research model. The two ‘Occupational Change in a Generation’ surveys in the US produced benchmark estimates of social mobility and spawned similar mobility surveys around the world (Blau and Duncan 1967, Featherman and Hauser 1978). Still other databases are influential because they provide basic data on social structure (e.g., income shares) which then play into other research. For example, many countries have an annual sociodemographic survey that yields income and employment statistics, which in turn drive research on poverty. To an increasing degree, the most influential databases are those which are based on systematic data collection over both space and time. Repeated data collection provides a fundamental tool for at-tacking some of sociology’s defining problems such as macro–micro linkages and the evolution of social structure. They also provide a framework in which one-time data collections can be understood. This research paper will argue that over time the core databases in sociology will be those which permit historical and cross-cultural comparisons.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Impact Of Data On The Discipline

Sociologists have argued for many years about the extent to which the physical sciences, particularly physics and chemistry, provide a model for doing sociology (Lieberson 1985). An argument can be made that geology is perhaps a better model. In that field, the scientific revolution known as the theory of plate tectonics resulted in large part from the study of the sedimentary record. Using deep cores and other tools, geologists have been able to reconstruct the physical history of the earth, along with its climate and biology, going back many millions of years. At the beginning, the data were collected in a somewhat a-theoretical way but as the picture became inductively clear, more focused data collection resulted (Van Andel 1985). This kind of interplay between data collection and theory development characterizes other fields as well. In biology, Darwin’s theoretical achievements were based on years of data collection and the theory of natural selection drew heavily on the geological record.

In sociology, the data accumulated over many centuries of human activity are somewhat analogous. While the time scale differs by several orders of magnitude, one can think of accumulated data from human activity in the form of government, religious and commercial records, and more recently from surveys, as the sediments that form the basis for social science research. As these records have become computerized the volume of data, and the ease with which it can be accessed, have increased dramatically. Of course, researchers have used surviving hard-copy data for a long time. Historical demographers have used parish registries to study family formation and economic historians have used commercial and government records to study price levels and other economic phenomena. But until very recently the availability of data was, to a large extent, accidental, based on nature’s whim and historical chance. Cover-age of topic, region, and time period was erratic and inconsistent. But in the last 50 years of the twentieth century, the information revolution has been laying the basis for a databased social science that is far broader and systematic than has been the case in the past.

There are several aspects of the revolution. First, much primary data are now being created directly in electronic form, thus increasing accessibility. Second, vast amounts of data can be stored at very low cost. Third, with the emergence of the Internet, data can be moved about the world almost at will. Finally, software for accessing the data and analyzing it is becoming easier to use, although much remains to be done. The revolution dates back to the early 1960s. Although there are certainly examples of machine-readable data collected before then, the flood began with the availability of second-generation computers to process data and machine readable tapes on which to store and ship it. Since then, a torrent of data has become available and the breadth and depth of the river is increasing daily. Two processes are going simultaneously. First, hard-copy data from old records and texts are being retrieved and converted to electronic form. For example, in the USA very large samples of decennial census records from 1850 to 1950 have been drawn from the original manuscript data and are available to be used in conjunction with contemporaneously created sample files from 1960 onward. More focused data conversion is also going on. To cite just one example from dozens available, the study of slavery in North America is being revolutionized by the conversion of old records such as courthouse registers and slave ship manifests (Eltis 1999, Hall 1999). Second, various data resources—not just surveys but electronic records of all kinds—are slowly accruing over time. For example, tables of live births by age of mother and race are available for the USA from 1933 to the present.

To see the impact of what is happening, imagine that the information revolution had begun a 100 years earlier, i.e., about 1860 rather than 1960. Suppose that the electronic information that social scientists now work with routinely—surveys, macro-economic data, administrative records of various kinds, detailed geographic information—had begun to emerge at the beginning of the American Civil War and in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. Events such as the Great Depression would be seen in the light of a number of other economic events for which similar data would exist. In the USA, the 70-year period beginning with the ‘Depression’ and followed by more than half a century of almost continuous economic growth would be seen in the light of a far more variable economy in the period from 1860 until 1930. In Europe, the effects of the breakup of the Soviet Union could be studied in light of similar political and social transformations that occurred after World War I. Of course, it cannot be assumed that the data would be perfect or complete, any more than it can be assumed that current systematic data collection will proceed unperturbed in the face of economic upheaval, civil strife, or environmental catastrophe. But even with gaps in coverage and quality, with 140 years of data it would be possible to do a kind of social science which is now only beginning to be visible. Gradually, as the database for social science research grows more sophisticated, sociology and related fields will undergo a databased revolution that will redefine both substance and method.

2. An Overview Of The Emerging Database

Although any classification is somewhat arbitrary, it is helpful to think in terms of five main categories of databases.

2.1 Cross-Sectional Micro Le El Social, Economic, And Demographic Data

Many countries conduct national demographic surveys, either as censuses or based on samples, and in some cases both. These surveys tend to focus on core demographic data: family formation, fertility, mortality, and related matters. Increasingly, however, they deal with education, income, health, and other basic social variables. If not full censuses, most of the surveys have relatively large samples sizes. It can be expected that more and more countries will conduct such surveys as the benefits of the data become obvious, and as the technology for doing the survey work becomes more widespread. The ‘Integrated Public Use Micro Sample’ (IPUMS) project provides access to US Census from 1850 to the present at www.ipums.umn.edu./IPUMS will soon be offering access to other national censuses, with plans to include multiple time points from 21 different countries. The US Current Population Survey is available back to the mid-1960s from www.unicon.com. Many other national statistical agencies carry out similar surveys. The Luxembourg Income Study, begun in 1983, provides somewhat similar data for more than 25 countries (www.lis.ceps.lu).

2.2 Cross-Sectional Omnibus Social Surveys

Focusing on Social Behavior, Attitudes, and Values The GSS is perhaps the premier example of an omnibus survey. The International Social Survey Program (ISSP), which currently contains data from 31 countries, is linked closely to the GSS. Data and documentation can be obtained at www.icpsr.umich.edu GSS99 . An important feature of the GSS ISSP is its careful replication of measurement and methodology both over time and across countries. A somewhat parallel survey series, known as ‘Eurobarometer’ has been carried out between two and four times a year since 1974 (see http://europa.eu.int/comm/dg10/epo/org.html). Eurobarometer studies tend to be more topical and less focused on replication than the GSS.

2.3 Macro Level Economic And Social Data

Macro data consists of two kinds; data aggregated up to the micro level such as time and country-specific counts of crimes, and nondisaggregatable data such as balance of payments records. Among other organizations, the World Bank, the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development all provide data files and tables, varying in focus and coverage as do various academic institutions such as The University of Pennsylvania via its Penn World Tables (http://pwt.econ.upenn.edu/).

2.4 Micro Le El Longitudinal Surveys Of The Life Course

Since the mid-1960s, a number of studies in various countries have followed individuals longitudinally over long periods of time. They are important because they provide data on long periods of the life course within a particular historical context. Increasingly, the studies are being replicated, and one can study the flow of lives under differing social and economic conditions. For instance the US Health and Retirement Survey (www.umich.edu/hrswww/) provides data on the later life course for cohorts born after about 1920, with new cohorts entering the measurement sequence every five years.

2.5 Administrative Databases

Administrative records maintained by government and other organizations such as insurance companies, are potentially incredibly valuable resources. For example, a number of researchers in the US have been able to analyze survey data from studies of aging in conjunction with information from Health Care Financing Administration (Medicare) records (e.g., Wolinsky et al. 1995). These databases are usually not constructed with research in mind, and thus it is often time consuming to make effective use of them, but the accumulated data in various administrative databases can offer research opportunities available in no other way.

3. Issues To Be Resolved

Thus far, this research paper has been written as though there are no impediments to a new world of data. However, this is not the case.

3.1 Gaining Access To Data

Access to micro level surveys, particularly those conducted by national statistical bureaus, is often difficult. Some countries refuse access entirely and others sharply restrict it. When data files are released, confidentiality concerns often lead to sharp limitations on the availability of potentially identifying information, particularly geographic data. Researchers can often negotiate access to specific data files, but gaining simultaneous access to multiple data sets in multiple countries is often impossible. There are several approaches to the problem. The US Bureau of the Census has created several Research Data Centers, where closely controlled on-site access to restricted data is available to qualified researchers. Another approach is to devise disclosure limitation methodologies to protect individual identities in publicly available files. A third possibility is to make documentation public but require analyses to be run remotely on the agency’s computer with agency control over the analyses. Despite these initiatives, public concerns about confidentiality and privacy continue to impact legislation on data access in many countries. If the promise of the information revolution is to be fully realized, efficient ways of giving re-searchers access to data while satisfying privacy concerns will have to be found.

3.2 Ease Of Use

Anyone who has used a complex data set knows that the cost of getting into the data is high. Even the best data sets tend not be documented in such a way that outside researchers find it easy to use them. The problem has been exacerbated by the use of computer-assisted interviewing. Although computer-based inter-views have major advantages in data collection, one of which is to allow very complex survey instruments, they tend not to produce easily used documentation and the very complexity of the questionnaires makes the data difficult to use. Because the ‘questionnaire’ often consists of a series of computer screens, there is often no traditional hard-copy questionnaire, and producing one after the fact is difficult and time consuming. The research community has recognized the problem and there are various meta data projects under

way. One example is the ‘Data Documentation Initiative,’ an international project involving many social science organizations, which has developed mark up standards for machine-readable documentation (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/DDI/codebook.html). An application of DDI can be found at FASTER (http://www.nesstar.org/), a joint project of a number of European data and statistical organizations. There is also a good deal of work in progress to produce software that combines data collection, documentation, and analysis tasks. One example, which is freely available, is EpiInfo a software package for public health researchers developed at the US Centers for Disease Control (http: //www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/). There are also several competing commercial products under development at this point.

3.3 Design

As noted, with important exceptions, the accumulation of data is largely accidental. Within sociology, there is no grand plan to dictate what kind of data gets collected at what intervals. It is quite tempting to design studies to react to major political and social events, such as the breakup of the Soviet Union. Sometimes there is even ample time to anticipate an event, as was the case with welfare reform in the USA. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that slow, steady, systematic data collection offers the best chance of capturing the effects of unanticipated events and in any case provides an enormously powerful tool. The National Election Studies in the USA (www.umich.edu/nes/) provide a sequence of surveys going back to 1948. As the name implies, the principal use of the data has been to study national elections, but as a 50-year sequence of replicated surveys, the data also offer an almost unparalleled chance to study change in American society. With the exception of census data, it is very hard to find examples of systematic micro data series that go back further. It is very difficult for researchers anywhere to find the resources to maintain these kinds of studies over an extended period of time. But it seems clear that the steady accrual of systematic data while costly and by definition slow, is the only way to be sure that one has the right kind of data at the right time. Trying to spring into the field on short notice with the ideal design to study a particular topic or event is risky. This is not to say that short-term studies are valueless but rather to argue that short-term studies are most effective when a long-term framework of data using standard protocols and methods can support them.

3.4 Replication And Comparability

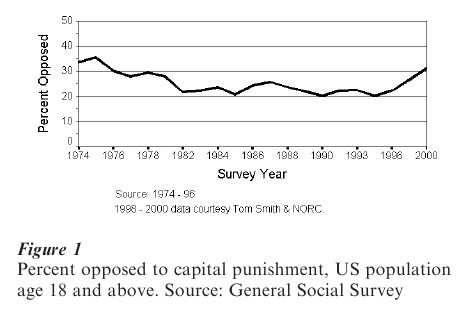

Perhaps the aspect of design that requires the most attention is measurement. Studying a given topic over the long term using multiple databases requires a certain amount of consistency of measurement. The GSS, for example, has maintained consistency of its basic items since its inception, and some of those items were taken from previous surveys that go back 20 years prior to the start of the GSS. Figure 1 shows GSS results from the US between 1974 and 2000 for the item ‘Do you favor or oppose capital punishment for murder.’ As the graph shows, opposition to capital punishment has increased since 1995, but is only now reaching levels that were common in the mid-1970s. The trend is too systematic to be accidental, and there are many possible explanations. It is tempting to speculate on the link between this trend and the fact that crime rates, particularly homicide, have fallen in the US for the past several years. The only point to make is that this comparison would have been difficult to impossible, had the wording of the item changed. Unfortunately, some items literally wear out as changing tastes and social conditions make them archaic or irrelevant, if not offensive, and some change is in-evitable.

Unfortunately, this kind of measurement and design consistency is rare, particularly for cross-cultural research. Researchers who wish to pool data from multiple surveys are usually faced with enormous inconsistency both within surveys over time and across surveys. Even within a given field, one finds differences in standard items across surveys. Often, there is no particular reason for the inconsistency; researchers just don’t think as much as they might about replicability. However, important progress is occur-ring. As noted, the ISSP has made great strides in obtaining comparable data across countries. There are several other examples such as the SF-36; a scale designed to measure health that is now in use in more than 45 countries (www.sf-36.com). A few fields of sociology, particularly social mobility, have made great progress in dealing with these issues. Ganzeboom et al. (1991) review mobility studies from more than 30 countries showing that it is possible to develop regression models that maintain at least rough comparability.

Despite the obvious advantages of consistency, there is a certain paradox here. Suppose that we find that when one operationalizes a set of constructs in exactly the same way, using exactly the same measurement protocols and survey design, one gets closely comparable results across multiple surveys. Is the similarity due to the ‘methods effect’ or does it represent true equality of results? In other words, one might like to show that the basic results replicate despite differences in measurement, sampling, etc. The answer to this question depends in large part on how closely one wants to compare results. To answer the question ‘have the economic returns to schooling changed over time?’ requires a great deal of consistency because answering the question requires exact comparison of regression coefficients. On the other hand, answering the question ‘are the relative effects of achievement and ascription the same in most industrial societies?’ might be answered, at least approximately, with something less than exact comparability.

3.5 Data Archiving And Preservation

An important aspect of the data revolution is the existence of data archives in many countries of the world. The idea of a data archive developed in the early 1960s when most data sets were in the form of decks of electronic data processing cards, a technology now virtually unknown. The card files were expensive to maintain and quite fragile, so data archives maintained master copies and provided duplicates to researchers. As the computing world moved to storing data on tapes, archives were sill needed as central repositories of data because the task of maintaining the data and making it available to users in a form suitable for their local computing facility, required technical skill and resources. A web-based world map of most of the major academic archives can be found at http://www.nsd.uib.no/cessda/other.html. The InterUniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) (www.icpsr.umich.edu) is the world’s largest academic archive with literally thousands of data sets, but there are a great many specialized archives around the world. A very thorough guide to archives and related facilities is maintained by the Social Sciences Data Collection at the University of California San Diego (http://odwin.ucsd.edu/idata/) where one can find links to hundreds of electronic resources.

The new world of the Internet is leading to radical changes in the nature of data archives. Currently, many data sets are made available directly on the web by the originating investigator or agency. This has obvious advantages in terms of accessibility, but perhaps less obvious disadvantages. Although Internet search tools are powerful, it is far easier to search the holdings of a few data archives than it is to search the whole Internet for data on a given topic. A more important issue is permanency. Archives are com-mitted to maintaining data and related documentation in perpetuity. Data maintained on local web sites is subject to all sorts of vicissitudes—funding disappears, investigators move or lose interest, servers crash, and technology changes sometimes rendering data un-usable. Indeed, archives have to worry about the fact that data on any storage medium deteriorates over time, as many users of compact disks know.

4. The Future

Although there is no question that social science will be affected profoundly by the availability of masses of data, a great deal must be done if the data are to be used to maximum advantage. Three issues seem to be the most important. First, the research community needs to pay closer attention to comparability and replication. The Internet has made that task vastly easier because data documentation can be moved about so easily. But the quality of the documentation varies a great deal and finding the information that one needs to know in order to either analyze the data or replicate the study, can be difficult to impossible. The development of efficient and effective electronic documentation and meta data is in the early stages and much remains to be done. Second, means of giving qualified researchers access to data must be worked out. In the current climate of serious concern about privacy, this will be a difficult task. On the other hand, the power of computing, when used properly, makes it easier to guarantee privacy rather than harder. Data can be encrypted, modified for public consumption to prevent disclosure, maintained at a single site to restrict access to qualified people, etc. There are slowly emerging methods and standards for how to do these things, but many issues remain to be resolved. Finally, and most importantly, there is the intellectual task of coming to terms with the stream of data that will be available. Until very recently, most researchers were content to focus their activities on a single data set. But as data accrue, for almost any question one is interested in, there will be multiple data sets available. Not only will there be multiple data sets across time and place, but there will be corresponding macro level data which might be relevant, as in the case of the GSS data on capital punishment, which can only be understood in light of societal level social and political factors.

Bibliography:

- Blau P M, Duncan O D 1967 The American Occupational Structure. Wiley, New York

- Eltis 1999 The Trans-Atlantic Sla e Trade: A Database on CD-ROM. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Featherman D L, Hauser R M 1978 Opportunity and Change. Academic Press, New York

- Hall G M 1999 Databases for the Study of Afro-Louisiana History and Genealogy, 1699–1860: Computerized Information from Original Manuscript Sources. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA

- Lieberson S 1985 Making It Count: The Improvement of Social Research and Theory. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Ganzeboom H B G, Treiman D, Ultee W C 1991 Comparative intergenerational stratification research: Three generations and beyond. Annual Review of Sociology 17: 277–302

- Van Andel T H 1985 New Views on an Old Planet: Continental Drift and the History of Earth. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Wolinsky F D, Stump T E, Johnson R J 1995 Hospital utilization profiles among older adults over time: Consistency and volume among survivors and decedents. Journal of Ger-ontological B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 50(2): S88–100