Sample Emigration Consequences Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

International migration is the movement of people across national boundaries. Emigration is international migration from the perspective of the migrants’ country of origin. Emigrant flows are the movements of emigrants with common origins or destinations, and emigrant stocks refer to the number of emigrants present in a destination. In many uses of the term, emigration involves a change in residence that is long term, although there is no single accepted definition of the length of time that a person has to be out of the country of origin in order to be considered an emigrant. Tourist or business related trips are not counted as emigration, whereas movements that involve a permanent change in place of residence are. Between these two extremes lies considerable ambiguity in deciding when an out-of-country movement becomes emigration. The United Nations defines a long-term emigrant as ‘a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for a period of a least a year (12 months), so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of residence’ (United Nations 1998, p. 10).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Part of the ambiguity in defining emigration arises from the presence of circular international labor migration. The development and expansion of international communication and transportation networks has stimulated and facilitated the movement of labor across national borders by increasing global access to information on living standards and employment opportunities in high-income countries, and by lowering the time and monetary costs of international travel. Labor recruitment activities targeted at workers in low-income countries and statesponsored guest worker programs have played an important role in generating and sustaining the international flow of labor. The same communication and transportation networks that facilitate emigration to high-income countries also facilitate return migration to emigrant places of origin. Recent approaches to emigration recognize the importance of return flows of information, financial resources, and emigrants. This research paper addresses the consequences in sending populations of both emigrant outflows and the return flows that emigrants generate. The consequences are divided into three broad groupings: demographic, economic, and social.

1. Measuring Emigration

Measuring emigration is difficult because it is a dynamic, duration-dependent process—a migrant is not necessarily an emigrant at the time of departure, but rather becomes an emigrant after a period of time in the country of destination. Although it is possible to measure intended length of stay at the time of departure, migrant intentions often change and not all international moves are legally sanctioned and thus documented at the point of departure or arrival. Many governments do not register departures or collect information on international migration flows. Lack of comparability across countries in the migration statistics reported makes it difficult to derive precise estimates of emigrant stocks and flows.

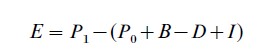

A number of approaches have been used to derive rough estimates of emigration using census and survey data. When emigrants from a country go to a small number of foreign destinations, information on place of birth from censuses conducted in the countries of destination can be used to estimate emigrant stocks and flows. Zlotnik (1992) used recent census data from countries in the Americas to estimate the number of emigrants from Latin American countries living in other countries in the region. Similarly, Hatton and Williamson (1998) used census data in major migrant receiving countries to estimate gross emigration rates in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for selected European countries. A second approach to estimating the magnitude of emigrant flows makes use of the demographer’s balancing equation:

The number of emigrants (E) is derived as the difference between the enumerated population at the end of the period (P1), and the expected population produced by natural increase (B D) and immigrant additions (I ) to the initial population (P0). Baines (1985) used a variant of this approach to estimate emigration from England and Wales in the late nineteenth century. A third approach to measuring emigration makes use of questions in household surveys about the international migration of current household members and nonresident relatives. Woodrow-Lafield (1996) used this approach to derive estimates of emigration from the USA, and Bean et al. (1998) used it to derive estimates of emigration from Mexico to the USA. The first two census-based approaches capture long-term emigration, but miss many short-term emigrants who are not present in the destination at the time of the census. The survey-based approach misses long-term emigrants who no longer have relatives in their community of origin, but is more effective at collecting information on short-term emigration and return flows.

2. Emigrant Flows

Migration scholars identify three periods of major emigration in the modern world (Massey et al. 1998). The first period, from 1500 to 1800, encompassed the flow of European emigrants into areas of colonization in the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, as well as the forced emigration of African slaves into the Americas. The precise number of European emigrants during this period is not known, but the number of African slaves was close to 10 million. The mass migration of Europeans to the Americas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marks the second major period of emigration. From 1800 to 1925, more than 48 million people emigrated from Europe in response to economic dislocations created by economic development at home and the availability of agricultural land and industrial employment overseas (Massey et al. 1998). Major emigrant-sending countries were the British Isles, Germany, the Scandinavian countries, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Poland, Russia, Spain, and Portugal. The third period of major emigration began in the 1960s and continues up to the present. Emigration in this period is marked by a major shift in origins. Most of the world’s emigrants now come from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Many of the former emigrant-sending countries in Europe have become important emigrant destinations.

Most emigrant flows are accompanied by significant counterflows of returning emigrants. The percentage of emigrants who eventually return to their country of origin varies substantially by period, and by country of origin, and destination. During the early periods of European overseas emigration return flows were relatively small because of the high cost of transportation. However, as the cost of intercontinental transportation came down, return emigration rose. At the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries the number of immigrants who left the USA to return to their countries of origin was equivalent to 30 percent of new immigration. While very few Russian and Irish immigrants returned, nearly 50 percent of Italian and Spanish immigrants to the USA returned home (Hatton and Williamson 1998). In the current period, the number of return emigrants in many national contexts exceeds the number of emigrants who remain in the country of destination. Emigrants are drawn back to their countries of origin by strong social ties at home, limited integration into the host societies— including legal restrictions on settlement put in place by the destination government—and the high purchasing power of emigrant earnings in low-income countries of origin (Appleyard 1998a).

3. Demographic Consequences Of Emigration In The Sending Population

Permanent emigration represents a loss of population in the place of origin. Whether this loss translates into a long-run reduction in population size depends on the age and sex composition of emigrant flows, and whether birth and survival rates rise in response to the loss of population. Malthusian population theory suggests that a reduction in the population pressure on existing resources through emigration could trigger a rise in birth and survival rates in the sending population. A demographic response of this type would cancel out or reduce the impact of emigrant loss on long-run population size. The development context within which most contemporary emigration originates makes a rise in birth rates an unlikely response to emigration. The same forces of economic development and modernization that stimulate emigration also operate to reduce fertility in the sending population. In general, countries that have experienced high emigration show lasting effects on future population size. For example, during the peak years of mass emigration, 1864–1914, emigration losses reduced potential population growth by 40 percent in Norway and by 25 percent in Sweden (Lowell 1987, p. 5). In Mexico, cumulative emigration to the United States has reduced the expected population of major emigrant-sending states by almost 50 percent (Verduzco and Unger 1998, p. 427).

The long-run effects of emigration on population size stem from the fact that emigration entails not only the loss of the emigrant but the loss of the emigrant’s descendants as well. The emigration of women who are ready to begin childbearing has a larger impact on long-run population size than the emigration of women who have completed childbearing. When emigration is selective of men, total fertility may also get below what it would have been because a greater proportion of women never marry. Ireland is an example of a country that experienced high rates of non-marriage among women due to the emigration of men.

The loss of emigrants and their descendants is associated with long-term or permanent emigration. Short-term emigration has separate but potentially significant effects on future population size. When emigration is temporary and sex-selective, it disrupts family formation and the pace of childbearing by delaying marriage and separating couples. Van de Walle (1975) provides evidence from the Swiss canton of Ticino of how the seasonal migration of men in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries stemmed population growth and led to low fertility by increasing the proportion of women who never married and by separating husbands and wives during their childbearing years.

4. Economic Consequences Of Emigration In The Sending Population

The economic consequences of emigration for the sending population stem primarily from the outflow of labor and the return flow of emigrant earnings (remittances). When emigration is voluntary and motivated by economic reasons, emigrants are overwhelmingly drawn from the working-age population. For the sending country emigration reduces the supply of labor, which in turn leads to lower unemployment and higher wages for those workers who remain. Hatton and Williamson (1998) find evidence that emigration from Ireland in the nineteenth century had precisely this effect—the departure of labor improved the economic conditions of non-emigrants faster than would have been the case if emigration had not occurred. Similarly, contemporary emigration in South Asia, much of which is directed toward oilproducing countries in the Middle East, has pushed up wages for skills that have become more scarce due to the temporary absences of workers (Appleyard 1998b). In addition to raising wages, emigration may induce the adoption of more advanced labor-saving technologies, and thereby speed up economic development (Simon 1989).

The impact of emigration on the aggregate supply of labor depends in part on the labor force participation of emigrants prior to departure and on the response of households to the loss of an emigrant worker’s labor. For example, in Sri Lanka close to two-thirds of emigrant workers are female household workers, many of whom were not in the labor force before emigrating. The effect of this emigration on unemployment in Sri Lanka is therefore difficult to measure because many of these women would not be in the domestic labor force if they had not emigrated (Gunatilleke 1998). Households may also respond to the emigration of a household worker by increasing the economic activity of remaining household members. This intrahousehold substitution of work diminishes the impact of emigrant departures on the labor market. For example, in countries where female labor force participation is low and emigration is selective of men, the substitution of women’s labor for men’s would alleviate any possible labor shortages created by emigration and would thus leave wage rates unchanged.

The emigration of highly skilled workers represents a loss for the sending country in terms of public investments made in their education and in terms of the economic growth that the emigrants would have generated if they had remained. Known as the brain drain, the emigration of highly educated and skilled workers is a cause of concern in emigrant-sending countries. The loss of potential new employment due to emigration is expected to be greatest when the skills possessed by emigrants and non-emigrants are complements of one another, that is, demand for one set of skills is dependent upon demand for the other. Not all emigration, however, represents a loss of skills for the sending country. Many emigrants return, some with new skills which lead to increased productivity at home. Of course, not all skills learned abroad are transferable to origin labor markets because of national differences in the level of development and in the demand for distinct skills. Many jobs performed by emigrants in high-income countries also provide little or no opportunity for acquiring new skills.

Each year emigrant workers send home, or return with, a portion of their earnings. The transfer of emigrant earnings (remittances) has important economic consequences in the sending population. At the macro-level, remittances from emigrant workers have been a ‘life saver’ for the economies of some countries. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, both major emigrant labor sending countries, remittances constituted about 70 percent of export earnings during the 1980s (Shah 1998, pp. 24–5). During the 1990s remittances amounted to 50 percent of exports in the Dominican Republic, and in El Salvador remittances were nearly as great as the volume of exports (Lowell and de la Garza 2000, p. 6). In addition to being an important source of foreign exchange, remittances are a substitute for scarce credit, and remittances spent on goods and services generate new employment. In an analysis of the effect of emigration and remittances on the labor market in El Salvador, Funkhouser (1992) found that the strongest effect of emigration occurs through remittances and not through the loss of emigrant workers. Money earned abroad and spent at home creates investment and employment opportunities in the provision of goods and services that remittances are used to purchase. The labor market impact of remittances will be greatest in the local areas where remittances are spent. Market towns in emigrant-sending regions, for example, may benefit more from remittances in terms of employment growth than rural emigrant-sending communities.

At the household level remittances significantly raise consumption levels and the overall standard of living. The most common use of remittances after covering day-to-day living expenses is investments in housing. Aside from meeting a basic need, putting remittances into residential real estate is a popular strategy for storing the value of saved emigrant earnings when other forms of investment or savings are not viable options. Residential real estate can be used to generate rental income, and it can be converted back to cash by being sold. The heavy use of remittances for household consumption as opposed to investment in economic production has lead to pessimistic assessments by some analysts of the capacity of remittances to stimulate economic development. One common argument is that labor emigration to high-income countries and the return flow of emigrants and remittances create a condition of dependence on emigrant earnings in sending communities. Studies conducted in emigrant-sending communities from diverse settings reveal substantial variation in the relative use of remittances for consumption and investment purposes, however. In some communities remittances have played a key role in agricultural modernization, in others remittances have spurred the development of cottage industries which produce goods for domestic and export markets. The use of remittances for productive investments appears to be influenced by local access to productive resources. Greater numbers of return emigrants use remittances for investments in agriculture and entrepreneurial activities in communities where the expected returns on productive investments are positive.

5. Social Consequences Of Emigration In The Sending Population

Many of the social consequences of emigration in sending populations are related, first, to the disruption of family life produced by temporary out-of-country absences, and, second, the diffusion of new ideas and behaviors brought back by visiting and returning emigrants. The emigration of selected household members leaves households divided across national borders. One of the consequences of the disruption of family life is a change in definitions of family roles and role relations. For example, in countries where male household members emigrate and female members stay behind, married women often become de facto household heads during their husband’s absence, and take on many of the roles otherwise reserved for men. The experience of greater autonomy in economic decision making can produce long-run changes in household gender roles. The prolonged absence of a spouse or parent also places families under stress, resulting in increased rates of family disintegration and divorce and a weakening of family control over youths. On the other hand the periodic absence of household heads, whether male or female, does not always have negative repercussions for families. In many low-income countries temporary labor emigration is a standard part of life, extending back several generations. Under these circumstances, family systems evolve and adapt coping mechanisms to meet the basic needs of emigrant and non-emigrant members (Thomas-Hope 1998). Kinship networks are often an important source of support for households with emigrant members.

During their visits to destination countries emigrants are exposed to new ideas, behaviors, and lifestyles that they gradually and selectively adopt. These new ideas, experiences, and behaviors are transmitted back to family and friends in the community of origin through correspondence, telephone conversations, and most importantly through visits and return migration. Levitt (1998) calls the ideas and norms that emigrants bring home with them, social remittances. ‘They include norms for interpersonal behavior, notions of intrafamily responsibility, standards of age and gender appropriateness, principles of neighborliness and community participation, and aspirations for social mobility’ as well as ‘expectations about organizational performance such as how the church, state, or the courts should function’ (Levitt 1998, p. 933). The circular flow of community members back and forth between the sending and destination communities produces continuous, sustained exposure to destination norms and behaviors. Emigrants and nonemigrants in places of origin filter, transform, and adapt these norms and behaviors to meet their own needs and circumstances.

Bibliography:

- Appleyard R (ed.) 1998a Emigration Dynamics in Developing Countries, Vol. I: Sub-Saharan Africa. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK

- Appleyard R (ed.) 1998b Emigration Dynamics in Developing Countries, Vol. II: South Asia. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK

- Baines D 1985 Migration in a Mature Economy: Emigration and Internal Migration in England and Wales, 1861–1900. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Bean F D, Corona R, Tuiran R, Woodrow-Lafield K A 1998 The quantification of migration between Mexico and the United States. In: Migration between Mexico and the United States: Binational Study. Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and US Commission on Immigration Reform, Austin, TX, Vol. 1, pp. 1–89

- Funkhouser E 1992 Mass emigration, remittances, and economic adjustment: The case of El Salvador in the 1980s. In: Borjas G J, Freeman R B (eds.) Immigration and the Work Force: Economic Consequences for the United States and Source Areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 135–75

- Gunatilleke G 1998 Macroeconomic implications of international migration from Sri Lanka. In: Appleyard R (ed.) Emigration Dynamics in De eloping Countries, Vol. II: South Asia. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, pp. 113–46

- Hatton T J, Williamson J G 1998 The Age of Mass Migration: Causes and Economic Impact. Oxford University Press, New York

- Levitt P 1998 Social remittances: Migration driven, local-level forms of cultural diff International Migration Review 32(4): 926–48

- Lowell B L 1987 Scandinavian Exodus: Demography and Social Development of 19th Century Rural Communities. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Lowell B L, de la Garza R 2000 The Developmental Role of Remittances in U.S. Latino Communities and in Latin American Countries. Inter-American Dialogue and Tomas Rivera Policy Institute, Claremont, CA and Washington, DC

- Massey D S et al. 1998 Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Clarendon, Oxford, UK

- Shah N M 1998 Emigration dynamics in South Asia: An overview. In: Appleyard R (ed.) Emigration Dynamics in Developing Countries, Vol. II: South Asia. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, pp. 17–29

- Simon J 1989 The Economic Consequences of Immigration. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Thomas-Hope E 1998 Emigration dynamics in the Anglophone Caribbean. In: Appleyard R (ed.) Emigration Dynamics in De eloping Countries, Vol. III: Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, pp. 232–84

- United Nations 1998 Recommendations on Statistics of International Migration. Statistical Papers, no. 58, rev. 1. United Nations, New York

- Van de Walle F 1975 Migration and fertility in Ticino. Population Studies 29(3): 447–62

- Verduzco G, Unger K 1998 Impacts of migration in Mexico. In: Migration between Mexico and the United States: Binational Study. Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and US Commission on Immigration Reform, Austin, TX, Vol. 1, pp. 395–435

- Woodrow-Lafield K A 1996 Emigration from the USA: Multiplicity survey evidence. Population Research and Review 15: 171–99

- Zlotnik H 1992 Empirical identification of international migration systems. In: Kritz M M, Lim L L, Zlotnik H (eds.) International Migration Systems: A Global Approach. Clarendon, Oxford, UK, pp. 19–40