This sample abortion research paper on reproductive ethics features: 3100 words (approx. 10 pages) and a bibliography with 27 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The goals of public health include improving the health status of populations, augmenting the ability of parents to raise healthy children, and maximizing the opportunities for individual self-determination. Abortion and contraception are only two among many interventions that may contribute to achieving these public health goals. The ethical considerations that public health practitioners apply to the provision of abortion and contraception include respecting the autonomy of individuals, seeking to minimize harm, acknowledging competing interests, and appreciating the fairness of providing access to health services for everyone.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

While there is extensive debate concerning the ethics of abortion and (to a lesser degree) all forms of fertility control, only those arguments that apply specifically to the field of public health are considered here. The same ethical principles underpin public health provision of all forms of fertility control. Using ethical grounds to distinguish between abortion and contraception suggests that women who are not yet pregnant (and therefore potentially contracepting) have a different moral status from those who are pregnant (and therefore potentially considering abortion). This distinction has become less meaningful following the widespread adoption of post coital fertility control methods such as menstrual extraction, pharmaceutical interception of pregnancy prior to implantation, and the use of contraceptive devices that interrupt implantation but not conception. The continuum between contraception and abortion technologies highlights the need for public health practitioners to rely on ethical principles that are applicable to both.

The Autonomy Of Women

The most significant ethical considerations of fertility control center upon the autonomy of individual women and their authority to make decisions regarding reproduction, their future, and their health care. Forced sterilization, surreptitious contraception, and compelled abortion are all unethical because each denies the autonomy of women.

Family formation, pregnancy, and childbearing have an enormous impact on women’s life chances. To be able to influence these events gives women the opportunity to enhance their own health and well-being. Women also seek to maximize the opportunities for the health and development of their children. For women who have very little opportunity to make decisions about their circumstances or their sexual relationships (such as those living with domestic violence, with drug dependency, or on the very margins of their society), fertility control may provide an opportunity to exercise self-determination and exert some influence over their future.

Respect for the autonomy of women requires their consent to all health interventions. In order to make informed decisions and provide consent, the risks of contraception, abortion, and childbearing must be understood. The risks associated with each of these vary according to the healthcare practices and products used and the social and economic context that prevails. Providing accurate information is an ethical and often a legal obligation. In many jurisdictions with a common law tradition, medical practitioners have a duty of care, and this duty includes providing warnings of the risks of treatment. Valid evidence concerning risk is required by both practitioner and patient to inform consent. There is a strong body of scientific evidence demonstrating the safety of the widely available forms of contraception as well as the safety of abortion.

Respect for autonomy also underlies the requirement for privacy. The concepts that a woman has a right to privacy and that decisions concerning abortion and contraception are private matters to be decided by a woman and her doctor were embodied in Roe v. Wade (1973), a U.S. Supreme Court decision that established access to abortion and identified the right to privacy as a facet of the U.S. Constitution. Privacy legislation adopted by many members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development is derived from the Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Information (OECD, 1980). These guidelines assert that people may control disclosure of personal information and that they have a right of access to the records kept about them.

The right of patients to expect confidential health care has been consistently defended by medical practitioners and public health advocates. Practicing confidentiality acknowledges the autonomy of patients by respecting their decisions about who may know their secrets. It also encourages patients to trust health providers with sensitive information that may be important in providing care. This has long been recognized as a prerequisite for treating sexually transmitted diseases and is necessary for the provision of all sexual health services, including contraception and abortion. In particular, sexually active teenagers will forgo sexual health care where they fear that confidentiality will not be protected (Marks et al., 1983; Zabin et al., 1999; Thrall et al., 2000).

Minimizing Harm

Another major ethical principle on which provision of contraception and abortion rests is the minimization of harm to women. Two questions arise from consideration of the ethical principle of nonmaleficence (do no harm). Is giving women decision-making authority over their reproduction harmful or health-enhancing to women, and is fertility control harmful or health-enhancing for women?

Is Self-Determination Harmful To Women?

Public health requires attention to a wide range of factors that contribute to well-being. When contraception and abortion are accessible, women may choose to raise a smaller number of healthier children. For women, opportunities to gain and maintain employment, participate in public life, and contribute to decision-making forums all enhance health. Women’s social participation is restricted by many factors. When child care is entirely the responsibility of mothers and employment conditions conflict with parental responsibilities, child rearing causes disadvantages for women seeking employment. When women are faced with discrimination, access to fertility control provides them with opportunities for self-development.

The ability to determine family size improves women’s sense of well-being irrespective of the number of children they bear. The contribution that control over family size makes to women’s well-being is illustrated by research such as that conducted by Hardee et al. (2004) in Indonesia.

Is Contraception Or Abortion Harmful To Women?

The very low risk associated with contraception or abortion conducted using safe techniques and the contrasting higher risks associated with childbirth and unsafe abortion are ethically significant. They indicate that generally available contraception is a harm minimization strategy and legally sanctioned abortion is the least harmful pregnancy outcome for women.

Consideration of potential harm to women has been important in framing legislation regulating abortion in many jurisdictions. Legislation may permit abortion when the risk to the pregnant woman from abortion is less than the risk of continuing the pregnancy (all pregnancies) or, more restrictively, when there is grave risk to the life of the pregnant woman if the pregnancy continues (few pregnancies). While legislation varies in the range of circumstances in which abortion is sanctioned, the underlying ethical principle embodied in these provisions is that the life of the pregnant woman is important and she will be permitted to take action that increases her chances of survival.

Assessment of risk has concerned legislators in regulating abortion in many jurisdictions. A concern that women may not act in their own best interests when choosing abortion has led to the substitution of another decision maker (often a judicial officer or a doctor) in some jurisdictions. The substitute decision maker is then called upon to decide whether the risks of abortion are acceptable in individual cases.

Where only unsafe abortion is available, women who seek abortion appear to act against their own best interests. The risk that women are prepared to face can be seen as a measure of the adversity that they expect in continuing an unwanted pregnancy. In societies in which the consequence of a pregnancy conceived outside marriage may include withdrawal of family support, social condemnation, or death for mother or child, women will choose abortion even when they are aware that the risk is high. Where women enjoy good health and child rearing outside marriage is possible, risks associated with contraception and abortion are less acceptable, both to women and to legislators.

Because contraception is widely used and abortion is very common, it has been possible to collect data concerning the associated risks across diverse populations (Winikoff et al., 1997). A low frequency of complications and low rates of contraceptive failure resulting in a pregnancy have been established. There is strong evidence demonstrating that the risk of death, physical injury, mental injury, or reduction in future fertility is very low following abortions conducted by trained practitioners using appropriate facilities. The risk of death from abortion using surgical (Kulier et al., 2005b) or medical (Kulier et al., 2005a) procedures is much lower than the risk of childbirth or other commonly performed surgical procedures (such as cesarean section). Women have lower mortality rates from all causes following an abortion than women who have not been pregnant (Gissler et al., 2004). There is no difference in the rates of mental illness between women who have had abortions and those who have not (Broen et al., 2004). There is no association between abortion and an increased risk of breast cancer (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee, 2003). There is some evidence of slightly increased risk of miscarriage or premature labor in subsequent pregnancies following either a miscarriage or an abortion (Henriet and Kaminiski, 2001; Sun et al., 2003). Both miscarriage and premature labor are relatively common, and the increase in risk is small in comparison to the background rate.

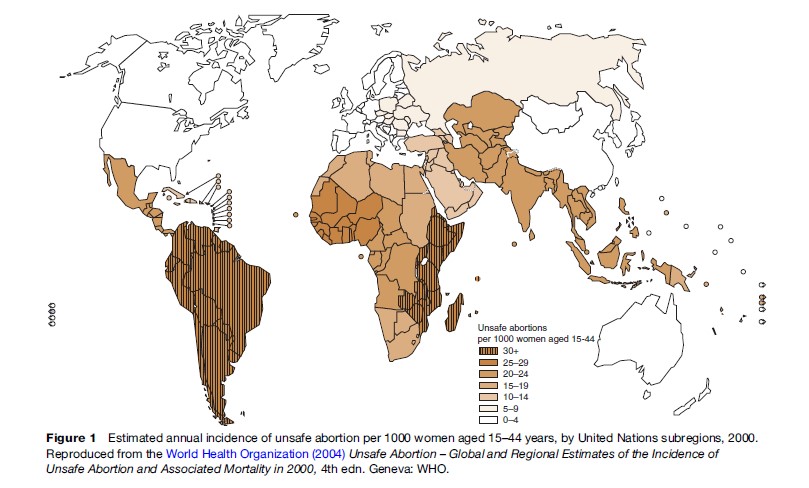

There is a significant contrast between the health risk associated with abortions conducted by appropriately trained practitioners using sterile techniques and those conducted in circumstances that do not support safe methods. These differences have been mapped globally by the World Health Organization (2004) in a report that estimates the maternal death rate attributable to unsafe abortion to be 1:270 (Figure 1). The harm that restrictive abortion laws cause to women’s health and morbidity are well documented, and world trends are toward liberalizing access to abortion (Cook et al., 1999).

Competing Interests

Ethical discussion of fertility control may focus entirely on women, overlooking the role of men as reproductive beings with responsibility for their own sexual activity and contraception. Men’s rights are most often discussed in relation to a right to paternity rather than in relation to their own responsibility to constrain their capacity to impregnate and make ethical decisions about paternity.

Two major areas in which third parties claim rights in relation to abortion are the rights of the fetus and the rights of men to fatherhood. All claims that a fetus has rights rest on the presumption of the moral personhood of the fetus. If personhood is accorded prior to birth, then a claim to the protection of that life follows. The moral status of the fetus is a matter of religious belief for some, and for others the stage of development or viability of the fetus (its ability to survive interdependently of its mother) is a marker of personhood. Many jurisdictions accord rights only to born individuals, while others allow intervention to sustain fetal life against a pregnant woman’s wishes and some outlaw abortion entirely because of the presumption of fetal personhood. When fetal (or embryonic) personhood is conceded, exercising rights on behalf of the fetus remains incompatible with the principles of the autonomy of, and nonmaleficence toward, the pregnant woman.

The ethical principle of proportionality is relevant in weighing competing rights claims, including male rights to paternity. The burden to a woman of continuing a pregnancy unwillingly is generally considered to far outweigh the benefit to the man in becoming a father. Claims by would-be fathers in a pregnancy that they have caused have been given very little legal or ethical standing worldwide. Although cases have been brought in U.S. and European courts by men seeking to prevent a woman from having an abortion, these rarely succeed, primarily because recognition of paternal rights contravenes the principles of respect for the woman’s autonomy and informed consent. When the principle of proportionality is applied, the rights of the pregnant woman prevail.

Justice

Distributive justice is a key ethical principle that applies to the provision of social goods including public health services. Health services are an instrumental, rather than an absolute, good in that they are not good in and of themselves, but only insofar as they facilitate survival, human dignity, and full citizenship. The principle of distributive justice requires that health services be accessible to individuals according to need and within the context of resource availability. When there are barriers preventing access to contraception and abortion, distributive justice is compromised. Access to health care is often stratified by race, class, and region. This is also true for access to abortion and contraception. Many factors compromise access to fertility control, including material considerations, cost, availability, and religious or national policies.

Access to safe contraceptive and abortion services requires sufficient regulation of providers and manufacturers to ensure safe services. However, a highly regulated environment can compromise services. In some jurisdictions, regulatory mechanisms retard or restrict the distribution of contraceptives and medications and devices used for post coital contraception and abortion. Currently this restriction exists in some countries in relation to RU486 despite this drug being included on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines for developing countries (2005).

Access to contraception and abortion is also compromised when services are under attack, and when service providers and/or patients are intimidated and stigmatized. The marginalization of abortion services from mainstream health provision produces further barriers to access. These include difficulties in recruiting, training, and sustaining a skilled workforce, which compromise the quality of services.

Stigma associated with abortion and contraception creates an environment in which normal requirements for duty of care by medical practitioners can be compromised. For example, where law or practice allows health workers conscientious exemption, those practitioners who decline to provide services still have an ethical obligation to refer the patient for these services elsewhere.

Conclusion

Contraception and abortion are ethical when they result from informed, voluntary decisions by individual women. They support the woman’s agency and authority over her own life. They reflect the principle of bodily autonomy and maximize women’s opportunities to be healthy. In situations in which it is possible to provide contraception and safe abortion, these minimize maternal and infant deaths and enhance the health and social well-being of women and children. It is ethical to provide fertility control services for these reasons.

Self-determination and access to contraception and safe abortion are not harmful to women. In contrast, many maternal deaths are caused by unsafe abortion and childbirth without health care. Access to all forms of fertility control, including contraception and safe abortion, is contested across the world, with negative consequences for public health.

Although there are competing claims over a pregnancy, these do not outweigh the ethical value accorded to the autonomy of women and the benefits that flow from self-determination.

The ethical principle of justice supports access to health services for all people. Equitable and confidential access to contraception and abortion are part of any comprehensive public health system.

Contraception and abortion are not the only means of supporting women’s self-determination, ability to maximize their health potential, or their ability to raise healthy children. Education and economic independence are critical in supporting the well-being of women and their dependents.

Bibliography:

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee on Gynecology Practice (2003) AOG Committee Opinion. Induced abortion and breast cancer risk. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 83: 233–235.

- Broen A, Moum T, Bodtker A, and Ekeberg O (2004) Psychological impact on women of miscarriage versus induced abortion: A 2 year follow-up study. Psychosomatic Medicine 66: 265–271.

- Cook R, Dickens B, and Bliss L (1999) International developments in abortion law from 1988 to 1998. American Journal of Public Health 89: 579.

- Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle M, and Buekens P (2004) Pregnancy-associated mortality after birth, spontaneous abortion, or induced abortion in Finland, 1987–2000. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 190: 422–427.

- Hardee K, Eggleston E, Wong E, Irwantoth, and Hull T (2004) Unintended pregnancy and women’s psychological well-being in Indonesia. Journal of Biosocial Sciences 36: 617–626.

- Henriet L and Kaminski M (2001) Impact of induced abortions on subsequent pregnancy outcome. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 108: 1036–1042.

- Kulier R, Fekih A, Hofmeyr G, and Campana A (2005a) Surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4.

- Kulier R, Gulmezoglu A, Hofmeyr G, Cheng L, and Campana A (2005b) Medical methods for first trimester abortion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4.

- Marks A, Malizio J, Hoch J, Brody R, and Fisher M (1983) Assessment of health needs and willingness to utilize health care resources of adolescents in a suburban population. The Journal of Pediatrics 102 (3): 456–460.

- Mulligan E and Braunack-Mayer A (2004) Why protect confidentiality in health information? A review of the research evidence. Australian Health Review 28: 48–55.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1980) Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Information. Paris, France: OECD. Roe v. Wade (1973) 410 U.S. 113.

- Sun Y, Che Y, Gao E, Olsen J, and Zhou W (2003) Induced abortion and risk of subsequent miscarriage. International Journal of Epidemiology 32: 449–454.

- Thrall J, McCloskey L, Ettner S, and Rothman E (2000) Confidentiality and adolescents’ use of providers for health information and for pelvic examinations. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 154(9): 885.

- Winikoff B, Sivin I, Coyaji K, et al. (1997) Safety, efficacy, and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba, and India: A comparative trial of mefipristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 176: 431–437.

- World Health Organization (2004) Unsafe Abortion – Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000, 4th edn. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- World Health Organization (2005) 14th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines Disease and Treatment. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Zabin L, Stark H, and Emerson M (1991) Reasons for delay in contraceptive clinic utilization, adolescent clinic and nonclinic populations compared. Journal of Adolescent Health 12: 225–232.

- British Medical Association (1999) The Law and Ethics of Abortion: BMA Views. London: British Medical Association.

- Cohen AL, Bhatnager J, Reagan S, et al. (2007) Toxic shock associated with clostridium sordellii and costridium perfringens after medical and spontaneous abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1101(5): 970–971.

- Hakim-Elahi E, Harold MM, Tovell MD, and Burnhill MS (1990) Complications of first trimester abortion: A report of 170,000 cases. Obstetrics & Gynecology 76(1): 12935.

- Henderson JT, Hwang AC, Harper CC, and Stewart FH (2005) Safety of mifepristone abortions in clinical use; A review of 195,000 cases. Contraception 72: 175–178.

- Mulligan E (2005) Striving for excellence in abortion services. Australian Health Review 30(4): 468–473 (outcomes following 35,000 South Australian cases).

- Reime B, Schu¨ cking BA, and Wenzlaff P (2008) Reproductive outcomes in adolescents who had a previous birth or an induced abortion compared to adolescents’ first pregnancies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth Jan 31: 8, 4.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004) The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

- Visintine J, Berghella V, Henning D, and Baxter J (2008) Cervical length for prediction of preterm birth in women with multiple prior induced abortions. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 31(2): 198–200.

- World Health Organization (2003) Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidelines for Health Systems. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- Zhou W, Gunnar LN, Moller M, and Olsen J (2002) Short-term complications after surgically induced abortions: A register-based study of 56117 abortions. Acta Obstetetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 81: 331–336.