Sample Feminist–Economist Critique of Family Theory Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. Feminist Economics

The critique from feminist economics of economic family theory largely has been directed at the version developed in neoclassical economics, often referred to as the ‘new home economics,’ though Marxist economic approaches to the family have also come in for their share of the criticism. The latter approaches largely were explicated in the ‘domestic labor debates’ of the 1980s, with articles appearing on both sides of the Atlantic showing how Marxist concepts could be used to study household production. Both these bodies of family theory were developed mostly in the 1970s, though their origins go back to the nineteenth century and even earlier.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Feminist economics can also be traced back to earlier centuries, but it emerged as a discipline in its own right in the 1970s and has grown most strongly in the 1990s. It is the branch of economics that seeks to understand the economic aspects of the relations between women and men and the gendered aspects of economic activity. With this dual goal of inquiry, feminist economics substantially broadens the scope of human activity to which economics can be applied. While economics is most commonly defined as the study of the allocation of scarce resources to meet human needs, in practice that study has been limited to primarily market transactions. Scarcity implies choice and neoclassical economics generally posits that ‘economic man’ acts rationally to maximize his own well-being, choosing options subject to constraints. Feminist economics suggests broadening the scope to a comprehensive study of provisioning and distribution, or to how society meets all its needs for everyone (Nelson 1993).

This would include housework and home production as well as the labor of caring for others, much of which is done by women within the family. Caring necessarily intertwines affection and work, and maximization of an individual’s self-interest may not be the guiding principle of this type of production, requiring that, at a minimum, the simple neoclassical model be made more complex. Since a monetary measure is absent, it is difficult to determine precisely how much production occurs in the household sphere, but worldwide it has been estimated that one-third of all human production results from the unpaid work of women (UNDP 1995, p. 97). Feminist economists argue that if these aspects of economic activity are not considered, one has a very incomplete view of the economy.

As Peterson and Lewis point out in the introduction to their 800-page compendium on feminist economics (Peterson and Lewis 1999), this is a branch of economics that welcomes diversity and heterodoxy. Feminist economists borrow from many traditions of economic thought as well as insights from other social science disciplines (Kuiper et al. 1995). While some feminist economists work largely within the neoclassical tradition and seek to use its methods to answer feminist questions, others work more within the Marxist framework or institutional economic tradition, while yet others use philosophical, literary, or postmodern methods. Most agree, however, that traditional economics of all schools has failed to explicate the economic aspects of gender relations, specifically the differences in economic power between women and men or the subordination of women to men. Why do women earn less than men, on average, just about everywhere, why do women do most of the family care in virtually all human societies, why do men hold most of the positions of economic leadership as owners, top managers, financiers, and so on?

2. The Neoclassical Theory Of The Family

Neoclassical economists did not turn their attention to the question of how economic factors affect decision-making within the family and the allocation of the time of family members among various pursuits until the market started to impinge on the family and to change family dynamics in an obvious way when labor force participation by married women began to grow in the United States in the 1960s. Before this period, the family was thought of mainly as a consumption unit spending income earned by the man of the family, who went outside the family to produce goods and services for the marketplace. As Albelda (1997) notes, this was the typical family arrangement of the white, middle-class men who founded the separate discipline of economics and increasingly professionalized it in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United States and Europe.

Becker (1965, 1973) and Mincer (1962) developed a model of the family unit in which men who specialize in market work (at which they are assumed to be relatively more efficient) and women who specialize in domestic production (at which they are assumed to be relatively more efficient) marry each other and maximize their joint satisfaction in a sort of trade exchange based on their comparative advantages. Each human needs both market goods and home-produced goods to survive (since the goods are substitutable but not perfectly so). If relative prices were to change, women and men would decide to trade different amounts with each other. The division of labor within the family (and the supply of family members’ labor time to the market) can change with the male–female wage differential, changes in male–female productivity in housework, and the availability and quality of substitutes, all of which can be affected by technological change. Rising real wages, especially for women, would tend to lead women to work more outside the home, substituting market-based goods and services for their housework time. Fertility will decline as women will want to spend more time at market work and less at home production. Moreover, as technological change occurs and society becomes more complex, the quality of children (their education and socialization) becomes more important than their quantity. More market-based goods (more education and better food and clothing) can be combined with fewer children to yield higher quality output (children with more human capital). In this way the productivity of home production keeps pace with the growing productivity in market-based goods. In the several decades since its origins, the neoclassical theory of the family has been developed by the work of many economists carefully examining such issues as the allocation of time, the supply of labor, the development of human capital, population growth, and economic development.

The neoclassical approach views the household’s role in the larger economy and society as the provision of labor to the market and the consumption of final products provided by the market. The household center (or factory) which performs these two functions combines market work, nonmarket work, and consumer products in an economically rational way: the mainspring of the system is the choice of individuals—who, faced with market options and given their own preferences and relative productivities, allocate their time and money accordingly. Thus, household production is the creation and maximization of utility to consumers in the household. It is assumed that the members of the household have harmonious interests which can be maximized by joint effort and decision-making (Hartmann 1974).

3. The Feminist Critique

Feminist economics challenges nearly every aspect of neoclassical economics. First, feminist economics challenges the limited role accorded the family or household, noting that caring labor is a large part of social reproduction and involves not only creating new laborers by raising children and maintaining adult workers through daily care but also the care of those unable to work, not only the young, but also the sick, disabled, and elderly. Women’s unpaid family work also includes maintaining kin networks and relationships, which provide a type of social insurance for the family. Women also contribute volunteer time to school, neighborhood, religious and community groups, which provide necessary services to family members, especially in countries without extensive welfare state services. Elson (1994) refers to all this crucial social reproductive work as the ‘caring economy,’ a term which brings its importance to the fore. The quantity and quality of the actual labor that takes place in the family is seldom examined carefully by neoclassical economists and thus the family portrait they paint is simplistic and incomplete. Too often women’s caring labor is not seen as skilled work that must be learned but rather as an innate ability that women have, or as the manifestation of their natural affection.

Moreover, since in feminist economics caring labor combines affection and work, economic rationality and love, or its withering away, may dictate different ‘choices.’ A disabled child almost always requires more care and attention than an able-bodied one, yet investing more in such a child who most likely will be less productive hardly seems economically rational; such a ‘choice’ may be more a matter of affection and love than one of economic rationality. Economic rationality implies ‘free’ choice, choice that is not fundamentally coerced even though it is faced with constraints. If love or affection has waned, even otherwise enjoyable activities like sex could become oppressive. Women sometimes stay on even in violent relationships because their alternatives seem so limited to them—can such behavior be deemed a free or rational choice?

Second, the neoclassical economics model assumes choice by individuals of different relative productivities exercising their individual preferences, but it fails to explain why domestic labor is most often performed by women. It offers no convincing explanation of why this would be so (other than to assert that women’s and men’s abilities and preferences differ markedly on average, an assertion that has not been proved). Moreover, one cannot just assume that men’s and women’s preferences are determined individually. Instead, social roles may rather be collectively determined or politically enforced to such an extent that it is difficult for an individual to express a different preference. Even in the present-day United States, where it is common knowledge that there is increased flexibility and diversity in family structures, a typical married mother may seem to make an individual choice to stay home and care for the children because her wage rate is lower than her husband’s, yet the wages women and men face in the labor market are affected by societal norms, including discrimination against women. As much as she might like to work, given her wage and the cost of childcare, she may have no individual choice to make. Also, the neoclassical model assumes that on the margin men and women can make individual decisions about time allocation, and that an individual could choose to work 33 hours per week, or 17 hours, or 51. In practice, the ‘choice’ of the number of hours of work is also largely socially determined by the convention of the 40-hour workweek as full-time work. And in some countries, for the most part only full-time jobs come with all the fringe benefits (health insurance, unemployment insurance, and pensions) that families need. Such benefits are difficult to get elsewhere.

Third, it is hard to see whose utility is being maximized, since nothing in economic theory suggests that two adults often have identical utility functions. Sometimes neoclassical economics seems to assume a joint utility function; at other times the possibility of altruism enters, in which, for example, the male head makes altruistic decisions within the family but acts in a completely self-interested way in the market place. In reality it is most logical and quite common that men and women in families often have different interests, preferences, and utility functions, as do parents and children (Hartmann 1981, Folbre and Hartmann 1988, Woolley 1999). Neoclassical economics does not deal well with the possibility of serious conflict in the family.

Fundamentally, feminist economists challenge this model because it justifies the status quo of the gendered division of work, labor and care within the family. It assumes that women are disadvantaged socially, have less access to the economic resources of good wages and property, and are often oppressed by individual men. It, therefore, hides what feminists are most interested in explaining. As Galbraith (1973, p. 25) has put it, neoclassical economists have made the concept of the household ‘a disguise for the exercise of male authority.’ Albelda (1997, p. 119) writes: ‘At the most fundamental level, neoclassical economics argues that women receive lower wages than men and perform more unpaid labor than men largely out of women’s and men’s own rational choices and desires.’

4. Marxist Domestic Labor Debates And The Feminist Critique

A debate about the unique aspects of production in the home took place within the Marxist economic school of thought in the 1970s, but it was never resolved. Does housework, like wage work, produce surplus value that is appropriated both by capitalists (who can pay workers a lower wage than they otherwise could) and/or by husbands (who appropriate personal services and who have a higher standard of living than they would otherwise)? Does home production constitute a separate mode of production, a feudal mode, directly appropriated by the lord of the house, rather than a capitalist one based on wage labor?

As Himmelweit (1999) notes in a useful review, this debate was part of a feminist attempt to use Marxist economics to identify the material base of women’s oppression. Since the Marxist framework gives prime attention to production, housework (i.e., the unique work of women) was scrutinized. Thus, earlier than in neoclassical economics, the actual content of housework was studied and theorized, but just as in the neoclassical domain, the role of housework had to be discovered by women. Just as the first neoclassical ‘new home economics’ treated the family as an unexamined black box with a unitary utility function, early Marxist analysis of the family generally suggested that the reproduction of the working class could safely be left to itself (i.e., to the invisible labor of women in the home). Since then the concept of housework as production has been firmly established and the importance of the changing nature of the boundaries between the spheres of domestic production and market production is understood everywhere. But the feminist critique also established that what is unique in women’s work in the home to reproduce the next generation is ‘its caring and relational aspects’ (Himmelweit 1999, p. 133).

5. The Development Of A Feminist Model

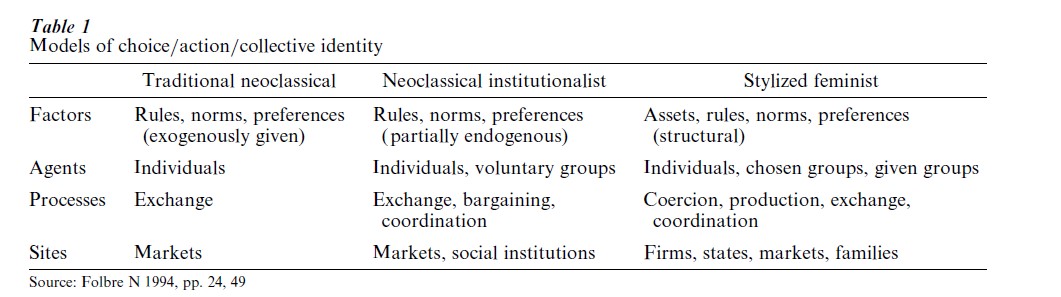

Using aspects from three major streams of economic thought, namely the neoclassical, institutional, and Marxist approaches, Table 1 describes the attributes of the ‘traditional neoclassical; model of the family (or economic decision-making more generally) in column 1. The table also shows how they are modified when institutional perspectives and feminist critiques informed by Marxist and institutional economics are added. (The table has been adapted from Nancy Folbre’s (1994) much cited Who Cares for the Kids?) In column 2 it shows that neoclassical institutionalists modify the simple model and emphasize that rules, norms, and preferences are not all exogenously given but are at least partially endogenous. As Folbre notes, it is often easier to act based on norms and on what everyone else is doing than to calculate each decision anew. Individuals also sometimes act collectively. Folbre argues that these modifications come largely from institutional economics, which rejected both individual choice and Marxist class analysis and instead emphasized group behavior by voluntary interest groups, such as labor unions (Figart and Mutari 1999). This model notes that a transaction can involve bargaining and cooperation (based on love and affection) as well as simply buying and selling at fixed prices, particularly within the family, where there are no fixed prices at which a wife can sell her homeproduced services to a new husband. Maximization of self-interest exists side by side with altruism in real life. One fruitful area of feminist research within this modified neoclassical framework is the use of game theory and models of cooperative and noncooperative bargaining to elucidate gendered outcomes in the family. (See Seiz 1999, for an overview, critique, and suggested extensions of this work.)

As the third column in Table 1 shows (the ‘stylized feminist’ description), not only are rules, norms, and preferences structural, but so are the assets with which the different parties begin the transaction. Using the concepts of material base and unequal ownership of assets from Marxist economics, feminist economists note that the genders do not come to the playing field as equals. Feminist economists also note that individuals do not choose all their group memberships, as the institutionalists often assume; many such memberships are assigned at birth. And, as in Marxist economics, important economic transactions are likely to involve coercion and production as well as cooperation and exchange. The relational aspect of caring is captured in the process of cooperation. Thus, in this example of a feminist model, the traditions of neoclassical, institutional, and Marxist economics are all challenged and incorporated in changed forms.

6. Impact Of The Critique From Feminist Economics

The emergence of common elements of feminist approaches, from whichever economic framework they start, has contributed to a considerable policy impact of the feminist economic critique. The recognition of the different work, interests, and utilities of wives and husbands, mothers and fathers, and the durability of unequal gender relations within the family, has informed the policies of economic development and family planning around the world. The success of these policies requires an understanding of women’s roles in the family and nonmarket production. Empirical research has shown that mothers use economic resources more for the welfare of children than do fathers both in more and less advanced countries.

Hence empowering women through education and employment is thought to be the surest way to improve the health and education of children and to raise a country’s productive capacity in the long run. More economically conservative structural adjustment policies, often fostered by international financial institutions to curb inflation and public deficits, seek to shrink the public sector and lessen wage demands. These policies have been shown to have disproportionately negative impacts on women, who try to make up for the lack of market wages and government aid through more intensive unpaid work. The limits of women’s ability to absorb the costs of adjustment necessarily limit the success of these and other macroeconomic policies. Feminist economic analysis has led to the understanding that integrating women into paid work or into production for market exchange is not sufficient to overcome gender roles that remain unequal in the family, nor is it enough to call for more grassroots activism to allow affected women to participate in policy discussions (Bakker 1999). It calls instead for ‘gender mainstreaming’ or putting gender issues at the center of policy changes everywhere, including in international agencies such as the FAO, ILO, and UNDP.

National and international statistical efforts have also become informed by the feminist economic critique of the family model. For the first time, the UN Platform for Action from the Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995 endorses the measurement of all unpaid labor activities, including those for own consumption in the household (i.e., housework). It also endorses their inclusion as satellite accounts in the System of National Accounts for each country (Vanek 1996). In its 1995 Human Development Report the UNDP for the first time included measures of work-time, covering both paid and unpaid time, for women and men. Its data for 31 countries show that everywhere women work more hours than men. Beneria (1996) has called for the continuous collection and analysis of such data from all countries to better measure the effects of policy changes, such as structural adjustment policies. In the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics is considering a regular, periodic survey of time use (Committee on National Statistics 2000).

Feminist economists call for new measures of family poverty that challenge the assumption of income pooling and equal sharing within the family (Shaw 1999). In the United States feminist analysis of poverty, single mothers, and welfare reform calls attention to the similarity of women’s income pack-aging strategies across class—women package income from men or other family members, their own labor market participation, and government programs (such as welfare, unemployment compensation, or social security). Just as most middle-class married women now work both inside the home for no pay and outside the home for some pay, most mothers who receive welfare or welfare-state benefits do not rely on it alone but combine income from paid work and from other family members with their government benefits. But we still know too little about who controls income within the family and how resource allocation decisions are made (Spalter-Roth et al. 1995).

7. The Growth Of Feminist Economics

The establishment of a list serve for feminist economists (Femecon-L) in 1991; the formation of the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) in 1992; its annual conferences held in diverse locations around the world; its regular presence as the sponsor and co-sponsor of sessions at the annual meetings of the Allied Social Science Association in the United States and in many other associations in many countries; and the founding of its journal, Feminist Economics, first published in 1995, have all contributed to the growing visibility of feminist economists and their ideas (Shackelford 1999). As is characteristic of so much other growth in social science in the past several decades, the development of feminist economics is distinctly diverse in method and approach, distinctly international in scholars, and distinctly global in its impact.

Bibliography:

- Albelda R 1997 Economics and Feminism: Disturbances in the Field. Twayne Publishers, New York

- Bakker I 1999 Development policies. In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 83–95

- Becker G S 1965 A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal 75: 493–517

- Becker G S 1973 A theory of marriage, Part I. Journal of Political Economy 81: 813–46

- Beneria L 1995 Toward a greater integration of gender in economics. World Development 23(11): 1839–50

- Beneria L 1996 Thou shalt not live by statistics alone, but it might help. Feminist Economics 2(3): 139–42

- Committee on National Statistics 2000 Time-Use Measurement and Research: Report of a Workshop. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

- Elson D 1994 Micro, meso and macro: Gender and economic analysis in the context of policy reform. In: Bakker I (ed.) The Strategic Silence: Gender and Economic Policy. Zed Press and the North-South Institute, London

- Figart D M, Mutari E 1999 Feminist political economy: Paradigms. In: O’Hara P A (ed.) Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 335–7

- Folbre N 1994 Who Pays for the Kids? Gender and the Structures of Constraint. Routledge, London and New York

- Folbre N, Hartmann H I 1988 The rhetoric of self-interest: Ideology and gender in economic theory. In: The Consequences of Rhetoric. Klamer A, McCloskey D, Solow R (eds.) Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK, pp. 182–206

- Galbraith J K 1973 Economics and the Public Purpose. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

- Hartmann H I 1974 Capitalism and Women’s Work in the Home, 1900–1930. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University

- Hartmann H I 1981 The family as the locus of gender, class, and political struggle: The example of housework. Signs 6(3): 366–94

- Himmelweit S 1999 Domestic labour. In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 126–35

- Kuiper E, Sap J, Feiner S, Ott N, Tzannatos Z (eds.) 1995 Out of the Margin. Feminist Perspectives on Economics. Routledge, London and New York

- Mincer J 1962 The labor force participation of married women. In: Gregg H (ed.) Aspects of Labor Economics. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

- Nelson J A 1993 The study of choice or the study of provisioning? Gender and the definition of economics. In: Ferber M A, Nelson J A (eds.) Beyond Economic Man: Feminist Theory and Economics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 23–36

- Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) 1999 The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA

- Shackelford J 1999 International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE). In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 486–9

- Seiz J A 1999 Game theory and bargaining models. In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 379–90

- Shaw L B 1999 Poverty, measurement and analysis of. In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 634–9

- Spalter-Roth R, Burr B, Hartmann H I, Shaw L 1995 Welfare That Works: The Working Li es of AFDC Recipients. Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Washington, DC

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program) 1995 Human Development Report. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Vanek J 1996 Generate and disseminate! The UN platform for action. Feminist Economics 2(3): 123–4

- Woolley F 1999 Economics of family. In: Peterson J, Lewis M (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Feminist Economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, pp. 328–36