Sample Family And Consumer Sciences Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Family and Consumer Sciences is the study of relationships among individuals, families, and communities and the social, economic, political, biological, physical, and aesthetic environments in which they function. An early widely accepted definition stated:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

… in its most comprehensive sense (it) is the study of the laws, conditions, principles and ideals which are concerned on the one hand with man’s immediate physical environment and on the other hand with his nature as a social being, and is the study specifically of the relations between those two factors (Lake Placid Conference 1902).

Themes which characterize the field include (a) holistic, systems approach to the study of individuals, families, and communities, (b) interdisciplinarity as the field draws knowledge from the social, behavioral, and life sciences, from technology and engineering, and from the arts and humanities, and (c) integration and synthesis of concepts as they are applied to wellbeing. A continuum from discovery and integration of knowledge through its application in practical settings also is a defining characteristic of the field.

Most of the work of the profession fits this characterization; however, degrees of emphasis on particular elements and the desire to communicate that emphasis through nomenclature has led to the use of a variety of names. This is most evident in the naming of colleges in higher education institutions in the United States. Human ecology, human sciences, human environmental sciences, human resources, as well as family and consumer sciences are used to designate this field of study in the academy.

Family and consumer sciences is mission-oriented. As a profession, field of study, and critical science, the mission of family and consumer sciences is ‘the empowerment of families to function interdependently and the empowerment of individuals to perform family functions’ (Green 1996). The mission-oriented nature of family and consumer sciences is reflected in statements about areas of leadership for the profession, to wit:

(a) improving individual, family, and community well-being;

(b) impacting the development, delivery and evaluation of consumer goods and services;

(c) influencing the development of policy; and

(d) shaping societal change; thereby enhancing the human condition (‘The Conceptual Framework for the 21st Century’ 1994).

1. Definition And Body Of Knowledge

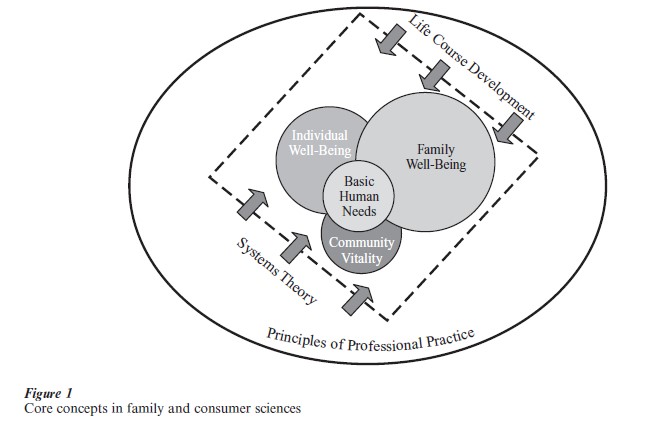

Family and consumer sciences is the study of relationships among individuals, families, and communities and the reciprocal relations of family to its human created and natural environments. Specific elements in the body of knowledge have varied somewhat over time. A task force of individuals from many of the organizations linked to family and consumer sciences began updating the specification of the body of knowledge in 2000. The work of this group is incorporated in Fig. 1, which depicts the core concepts in family and consumer sciences (Baugher et al. 2000).

1.1 Basic Human Needs

A primary expectation of families in most societies is that they work toward meeting basic human needs. Abraham Maslow’s conceptualization summarizes these needs as physiological needs (food, shelter, clothing), safety (security and the absence of fear), love and belongingness (human emotions connecting individuals in human systems), self-esteem (sense of competence and respect for self ), self-actualization (achieving one’s human potential) (see Paolucci et al. 1977).

Starting from the center of this model and moving outward, three interdependent concepts are represented: individual well-being, family well-being, and community vitality. Subsumed within these concepts, but not delineated, are multiple specific areas of research within family and consumer sciences. These concepts also represent the mission-oriented nature of family and consumer sciences. Together, the three areas reflect the ultimate concern of family and consumer sciences to enhance the quality of life.

1.2 Individual Well-being

Individual well-being refers to the promotion of a person’s physical and mental health, knowledge and skills, values, and civic responsibilities. Research in this domain may be as basic as studies to understand human metabolic processes and human genetic makeup, personality traits, or self-esteem as reflected in the selection of apparel. Application of this concept is reflected in numerous family and consumer sciences programs to increase knowledge and skills and foster more effective personal functioning.

1.3 Family Well-being

Family well-being is concerned with the development and dissemination of knowledge designed to empower families to meet the basic human needs of their members and engage in processes that build sustainable viable communities. Roles, responsibilities, and functions of the family have predominated the concerns of family and consumer sciences rather than structure (Green 1996). This is reflected in the definition of family adopted by the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences. Family is defined as ‘two or more persons who share resources, share responsibility for decisions, share values and goals, and have a commitment to one another over time’ (Bivens et al. 1975, p. 26).

In a statement on the ‘intellectual ecology’ of family and consumer sciences Green (1996) identifies the substantive core of family and consumer sciences as family functions. The family functions framework addresses the role of families in meeting the needs of its members (i.e., basic human needs). In the developed economy and contemporary society of the United States, there is great interdependence of families and other systems in producing the goods and services to meet these needs. Accreditation documents of the American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences have delineated these aspects of human needs in relation to the near environment that are of concern to family and consumer sciences (see Council for Accreditation 1995). The following concepts would generally be found in such a listing:

(a) Family systems, including economic, social, cultural, political, and demographic factors; family dynamics and roles;

(b) Interdependence of families and communities; (c) Human development across the life course;

(d) Resource development and management, including production, consumption, disposition, management and decision-making;

(e) Human nutrition and food in the development, health and wellness of individuals, families, and communities;

(f) Design and changing technology in relation to the development of home, community, and work environments that are supportive of consumers and families;

(g) Role of apparel and textiles in meeting the physical, social, and aesthetic needs of consumers and families.

1.4 Community Vitality

Community vitality fosters interdependency and collaboration designed to enhance the well-being of individuals and families. This concept may apply to those who reside in a specific locality or to groups who perceive themselves as a community based on shared interests and beliefs. Technology makes it possible to sustain community vitality in cyberspace. Community vitality can encompass the global community.

1.5 Systems Theory

A system is defined as interrelated elements having functional unity within a larger system. ‘Ecosystem’ is the regular interdependency of organisms within their environment. The basic concepts found in systems theory are development, relationships, interdependence, and reciprocity. The fundamental theoretical framework that gives family and consumer sciences its dynamic and integrative nature is family ecosystems. Paolucci et al. (1977) define family ecosystems as follows:

Family members, their external environments as perceived by them, and the web of human transactions carried out through the family organization constitute the basic elements of the family ecosystem. One fundamental characteristic of the family ecosystem is that it is made up of a collectivity of interdependent but independent parts working together to achieve a common purpose. Each element (organism and environment) is interrelated (p. 15).

Human ecology theory is congruent with family ecosystems, and human ecology theory is often identified as the theoretical foundation of family and consumer sciences. Bubolz and Sontag (1993) identify the uniqueness of human ecology theory as its ‘focus on humans as both biological organisms and social beings in interaction with their environment’ (p. 419). The use of the human ecological perspective is found in many social science disciplines and applied fields.

1.6 Life-Course Development

The concept of life course refers to a sequence of socially defined, age-graded events and roles that individuals enact over time (Elder 1998). Life-course thinking appears in most of the behavioral sciences scholarly literature after the 1960s.

As understood in life-course theory, human development is a co-active process in which social, cultural, psychological, and biological influences interact over time in the context of culture and social structures (Elder 1998). The concept of life-course development for individuals has been extended in family and consumer sciences to families, which also are observed to have experiences and characteristics described as life course events. An understanding of life-course development is important in family and consumer sciences because environments in which families function, and families themselves, change over time.

1.7 The Professional Context

As shown in the model, principles of professional practice are a part of the core concepts of family and consumer sciences. Brown and Paolucci (1979) identify three criteria for identity as a profession:

(a) A profession is oriented toward providing a service;

(b) The service involves intellectual activity, including practical judgment, which requires that the professional master theoretical knowledge related to the work;

(c) Members in the profession seek to assure that work within the profession is morally defensible both in nature and in the quality of performance.

Family and consumer sciences includes courses and experiences to facilitate a professional orientation with regard to ethics, valuing diversity, critical thinking skills, working in partnerships, and advancing policies that support the well-being of individuals, families, consumers, and communities.

1.8 Synergistic Integrative Approach

Family and consumer sciences claims as one of its distinguishing characteristics a ‘synergistic, integrative nature’ (Council for Accreditation 1995). The overlapping circles, dotted lines, and arrows in Fig. 1 depict this interplay among concepts. Addressing issues of wellness, for example, in the context of multiple factors rather than as isolated elements is the essence of the synergistic concept. For example, a dietitian needs to understand that obesity and impending cardiovascular disease are not just a matter of nutrition. Obesity is probably related to cultural food patterns, economic resources, and family relationships.

The integrative focus entails recognizing the interrelatedness of individuals, families, and consumers with their environments. In the example, the absence of sidewalks and parks with walking trails in a community may be a barrier to the state health agency’s goal of reducing obesity through fitness programs.

2. Specializations And Family And Consumer Sciences

Like a chameleon, family and consumer sciences is perceived differently by observers depending on the context and the ‘colors’ highlighted in that context. In the mid-twentieth century, Lee and Dressell (1963) observed three conceptions of the field, as follows:

(a) a single field with a broad general perspective and a number of specialties;

(b) a unified field with subspecialties embedded in the home and family;

(c) a collection of disciplines with no unifying theme or ‘anchor.’

Families may be recognized as the basic social unit of society, but technology and changing social norms increasingly influence how family functions are carried out. In economically developed countries, such as the United States, the household produces only a small portion of the goods and services it consumes. The family has become increasingly a managerial unit.

As family roles changed and new technology, products, and services emerged, specializations developed related directly to the family or derived from the functions of the family (e.g., providing food, shelter, nurturance, clothing, and reproducing children and culture) (Bailey and Firebaugh 1986). Some specializations developed around certain human issues (e.g., nutrition, dependent care of the young and the elderly, housing). Other specializations focus on the application of knowledge in business, industry and agencies (e.g., restaurant management, interior design, marriage and family therapy). Certain specializations may or may not be found in family and consumer sciences academic units. At the turn of the twenty-first century, examples of the three conceptions of family and consumer sciences can still be found in academic units in the United States.

3. History

Family and Consumer Sciences evolved from home economics. Home economics emerged at the turn of the twentieth century in the context of the progressive reform movement. The organizers of the home economics movement were educated women and men who deplored the problems associated with urban crowding, child labor, malnutrition, immigration, and lack of education; but they also believed that the application of scientific knowledge could improve the daily lives of people and the policies of public agencies and employers (Stage 1997, Vincenti 1982). They organized courses to improve nutrition and the management of resources in public schools and neighborhood organizations in Boston and New York City. They launched campaigns to reform corrupt practices of landlords, employers, and businesses. They advocated for responsible ‘municipal housekeeping’ in which government would improve living conditions and citizens would be involved in governing bodies.

The educational innovations of the 1860s, such as the creation of land-grant universities through the Morrill Act of 1862 (whose express purpose was to educate the children of the common folk), offered opportunities for higher education where they were not previously available. Home economics became a major point of entry for women into public higher education. The ‘second Morrill Act’ was passed in 1892, authorizing institutions of higher education for black citizens in the Southern States. The home economists who worked in the Extension Service and in the Southern schools and colleges worked in a segregated system with few resources (Harris 1997). Despite these constraints, their efforts greatly improved the daily lives of their constituents and offered career opportunities to those with formal education.

In 1899 began a series of meetings at the Lake Placid Club at Morningside, New York, for the expressed purpose of uniting efforts in the study of the home under one name and to organize a body of knowledge (see Brown 1985 and Lake Placid Conference Proceedings 1902–8). The proceedings record lively dialogue about nomenclature and content. Home economics was adopted as the name of the discipline. Ellen H. Swallow Richards, a chemist and the first woman graduate and first woman faculty member at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, emerged as a zealous leader for academic programs, demonstration and outreach projects, research, and professionalization of the field (Hunt 1942, Stage 1997). Ellen H. Swallow Richards is generally identified as the ‘founder’ of the home economics movement.

The growing strength of home economics in terms of students enrolled, organizational structure, and public policy advocacy is documented in Pundt (1980). She describes the first decade after the founding of the American Home Economics Association in 1909 as ‘continuing the struggle of the new discipline to define itself and find a rightful place among the more orthodox disciplines of a college or university …’ (Pundt 1980, p. 25).

Ideas about the modernization of family roles and the application of science in the home took a central place in home economics during the first quarter of the century. Behavioral sciences greatly influenced home economics teaching about child development and parenting, and child rearing was integrated into the home economics curriculum (Grant 1997). Principles from industrial engineering were applied to work simplification and design in the kitchens of America. Home economists were called upon during the 1930s to help families meet the devastation of the Great Depression. An outcome of these efforts was that nutrition and dietetics achieved a secure place in home economics curriculum and outreach programs (Babbitt 1997).

Dramatic changes in social roles, attitudes, and organization at mid-century and beyond prompted a series of conferences—New Directions (1959) and New Directions II (1975), the French Lick Conference (1961), the Eleventh Lake Placid Conference (1973), and Home Economics Defined (1979)—as the field engaged in a ‘search for identity’ (Brown 1985). The focus of most of these conferences and ‘white papers’ was the purpose and subject matter central to the field (Simerly et al. 2000).

In 1975, a definition of home economics was published in New Directions II:

The study of the reciprocal relations of family to its natural and man-made environments, the effects of these singly or in unison as they shape the internal functioning of families, and the interplay between the family and other social institutions and the physical environment (Bivens et al. 1975, pp. 26–27).

The Scottsdale Conference held in 1993 examined the mission, breadth, scope, and name of the field (Simerly et al. 2000, Stage and Vincenti 1997). The outcome of the meeting was the recommendation of the name Family and Consumer Sciences for the field, which was subsequently ratified by the sponsoring organizations. A systematic statement of the basic beliefs, assumptions, professional practice, and areas of focus was developed (The Conceptual Framework for the 21st Century 1994).

4. Research Methods

Research in family and consumer sciences covers the entire spectrum from empirical studies using survey research methods, experimental laboratory studies, historical analysis, qualitative research such as case studies and personal narrative, needs assessments, and evaluation studies. Both ‘basic research’ (i.e., research conducted for the sake of testing theory, or to study phenomena with no expectation of a utilitarian outcome) and ‘applied research’ (i.e., research directed toward the solution of specific problems) are found in family and consumer sciences (Touliatos and Compton 1988). Intervention projects based on experimental design are used to test the efficacy of programs aimed at behavioral change.

Certain research methods tend to be associated with specializations within family and consumer sciences. For example, nutrition, food science, and textile research tends to be conducted in laboratories using basic or experimental research methods. While animal models have long been used to study diet-related diseases, studies with human subjects are becoming more prevalent. Population studies based on the methods of epidemiology are employed in assessing the extent of dietary diseases.

Areas in textiles and apparel such as fashion merchandising and international trade adopt a variety of research methods ranging from historical analysis, psychometrics, and secondary data analysis. Textile scientists concerned with the environmental impacts of processing conduct field studies and operate pilot plants to investigate their research questions.

Demography is concerned with human population and changes over time, thus it plays a major role in social sciences and history. Family demography has traditionally been used to study macrolevel family patterns, but as life-course events are increasingly matters of choice, the importance of both macro and microlevel understanding is recognized (Teachman et al. 1999). Demographic methods are used to study housing, family economics, marriage, and fertility.

Research in family studies relies heavily on cross-sectional surveys and quantitative analysis. Data for these studies may be collected through interviews or self-administered questionnaires. Longitudinal analysis based on panel studies of the same subjects provide insights about families and their behavior over time. Acock (1999) observes that advances in computer technology and software facilitate the analysis of quantitative data which was not possible as recently as the 1970s.

Observational studies either in clinical or laboratory settings or the ‘naturalistic’ setting of the home are used to study family interaction. Qualitative methods are increasingly accepted as legitimate for the study of family and consumer issues. Qualitative family research uses content analysis of in-depth interviews, documents and other artifacts, and case studies (Rosenblatt and Fischer 1993). Qualitative studies are especially useful in the study of meanings, perceptions, and other subjective phenomena.

The mission-oriented nature of family and consumer sciences creates a close affinity for action research. The primary objectives of action research are solving problems and improvement of practice, but increased knowledge is also a potential outcome (Touliatos and Compton 1988). Participatory action research incorporates the indigenous knowledge of the community. Valuing such knowledge is important in facilitating societal change.

5. Outreach And Application

The Hatch Act, passed in 1887, provided funds to the States to establish agricultural experiment stations at the land-grant universities. The goal was solving practical problems. The Smith–Lever Act was passed in 1914, creating the Cooperative Extension Service. This provided the institutional vehicle for disseminating the research results from the universities and encouraging citizens to adopt practices to improve their living standards (see Babbitt 1997, Firebaugh and Redmond 1996, Harris 1997). The Cooperative Extension Service was a unique creation of higher education in the United States. It continues to have the most access to the most people through its network of county-based education programs.

The tradition of taking knowledge to the people has been modified through the years and adopted by family and consumer sciences programs, and many related social and behavioral sciences, in all types of higher education institutions. Community–university collaboration in identifying and addressing the problems facing families and youth in the United States is creating effective programs and solutions to many of these problems (Chibucos and Lerner 1999) and increasing the value of outreach scholarship within higher education (Lerner and Simon 1998). Limitations of space preclude a comprehensive review of the multitude of models and programs in which family and consumer sciences is in partnership with other disciplines and with constituents in the application of knowledge to address quality of life issues of the twenty-first century.

6. The Future

Family and consumer sciences has evolved with growing sophistication in research methods, proliferation of specializations within the field, use of new technologies for dissemination of knowledge, and advocacy for policies to protect families and consumers. The field, however, has remained focused on its mission. Fidelity to its mission and responsiveness to change are expected in the future.

Application of knowledge to persistent practical problems has characterized family and consumer sciences. The list of accomplishments is vast: the school lunch program, delineation of requirements for nutrients, standardization of clothing sizes, best practices models in dependent care, Truth in Lending and Truth in Saving legislation, to name a few. New issues present themselves in the twenty-first century. Most of these issues are complex and require multiple perspectives. More collaborative projects across the disciplines and with community groups can be expected in the future. New guidelines in federal and foundation funding, designed to foster a closer integration of research and application, will encourage family and consumer sciences researchers and practitioners to engage in more collaborative outreach efforts.

Increased availability of information through the Internet and rising education levels of the population are expected to change the focus of professional practice from an orientation of being an ‘expert’ to being a ‘facilitator.’ The holistic family ecosystems theoretical framework and the integrative, synergistic orientation of family and consumer sciences will provide a comparative advantage for practitioners working in the ‘information society.’

Deliberations about the nature of family and consumer sciences as a discipline are sure to continue. Conceptualizations about the body of knowledge (Baugher et al. 2000), discourse on the nature of the discipline (Brown and Paolucci 1979), and attempts to clarify and unify the discipline and the profession (Green 1996, Simerly et al. 2000) are echoes of the discussions at the Lake Placid Conferences. Such examination of family and consumer sciences will foster its future vitality and relevance as a field of study and a profession.

Bibliography:

- Acock A C 1999 Quantitative methodology for studying families. In: Sussman M B, Steinmetz S K, Peterson G W (eds.) Handbook of Marriage and the Family, 2nd edn. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 263–89

- Babbitt K R 1997 Legitimizing nutrition education: The impact of the Great Depression. In: Stage S, Vincenti V B (eds.) Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp. 145–62

- Bailey L, Firebaugh F M 1986 Strengthening Home Economics Programs in Higher Education. College of Home Economics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

- Baugher S, Anderson C I, Green K B, Nickols S Y, Shane J, Jolly L, Miles, J 2000 Body of knowledge of family and consumer sciences. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 92(3): 29–32

- Bivens G, Fitch M, Newkirk G, Paolucci B, Riggs E, St. Marie S, Vaughn G 1975 Home economics–New directions II. Journal of Home Economics 67(3): 26–7

- Brown M 1985 Philosophical Studies of Home Economics in the United States: Our Practical-Intellectual Heritage, Vol. I. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

- Brown M, Paolucci B 1979 Home Economics: A Definition. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Bubolz M M, Sontag M S 1993 Human ecology theory. In: Boss P G, Doherty W J, LaRossa R, Schumn W R, Steinmetz S K (eds.) Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 419–48

- Chibucos T R, Lerner R M 1999 Serving Children and Families Through Community-University Partnerships: Success Stories. Kluwer Academic, Norwell, MA

- Council for Accreditation 1995 Accreditation Documents for Undergraduate Programs in Family and Consumer Sciences, 1995 Edition. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Alexandria, VA

- Elder G H, Jr. 1998 The life course and human development. In: Lerner R M (ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology. Wiley, New York, pp. 939–91

- Firebaugh F M, Redmond M B 1996 Flora Rose: A leader, innovator, activist, and administrator. Kappa Omicron Nu Forum 9(2): 7–16

- Grant J 1997 Modernizing mothers: Home economics and the parent education movement, 1920–1945. In: Stage S, Vincenti V B (eds.) Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp. 55–74

- Green K B 1996 Our intellectual ecology: A treatise on home economics. In: Simerly C, Light H, Mitstifer D I (eds.) A Book of Readings: The Context for Professionals in Human, Family and Consumer Sciences. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Alexandria, VA, pp. 1–7

- Harris C 1997 Grace under pressure: The Black Home Extension Service in South Carolina, 1919–1966. In: Stage S, Vincenti V B (eds.) Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp. 203–28

- Hunt C L 1942 The Life of Ellen H. Richards. American Home Economics Association, Washington DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1901 Proceedings of the First, Second, and Third Conferences. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1902 Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1903 Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1904 Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1905 Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1906 Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1907 Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lake Placid Conference on Home Economics 1908 Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Lee J A, Dressell P 1963 Liberal education and home economics. Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York

- Lerner R M, Simon A 1998 University-Community Collaborations for the Twenty-First Century: Outreach Scholarship for Youth and Families. Garland, New York

- Paolucci B, Hall O A, Axinn, N 1977 Family Decision Making: An Ecosystems Approach. Wiley, New York

- Pundt H 1980 AHEA: A History of Excellence. American Home Economics Association, Washington, DC

- Ralston P A 1996 Flemmie P. Kittrell: Her views and practices regarding home economics in higher education. In: Simerly C, Light H, Mitstifer D I (eds.) A Book of Readings: The Context for Professionals in Human, Family and Consumer Sciences. American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences, Alexandria, VA, pp. 181–90

- Rosenblatt P C, Fischer L R 1993 Qualitative family research. In: Boss P G, Doherty W J, LaRossa R, Schumm W R, Steinmetz S K (eds.) Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 167–77

- Simerly C B, Ralston, P A, Harriman L, Taylor, B 2000 The Scottsdale initiative: Positioning the profession for the 21st century. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 92(1): 75–80

- Stage S 1997 Ellen Richards and the social significance of the home economics movement. In: Stage S, Vincenti V B (eds.) Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp. 17–33

- Stage S, Vincenti V B 1997 Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

- Teachman J D, Polonko K A, Scanzoni J 1999 Demography and families. In: Sussman M B, Steinmetz S K, Peterson G W (eds.) Handbook of Marriage and the Family, 2nd edn. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 39–75 The conceptual framework for the 21st century 1994 Journal of Home Economics 86(4): 38

- Touliatos J, Compton N H 1988 Research Methods in Human Ecology Home Economics. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA

- Vincenti V B 1982 Toward a clearer professional identity. Journal of Home Economics 74(3): 20–25

- Vincenti V B 1997 Chronology of events and movements which have defined and shaped home economics. In: Stage S, Vincenti V B (eds.) Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp. 321–30