Sample Family Health Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The very diversified topic of family health is currently receiving increasing attention from different disciplines and different directions within psychology. This is especially evident in the areas of clinical and family psychology, gender-specific research, and health psychology. In this research paper, important theories and empirical results from these fields are summarized in a systematic overview which is divided into the following sections: (a) the bidirectional connections between family dimensions and the health of family members (e.g., the mother), (b) systemic concepts like ‘psychosomatic families’ or ‘family mental health,’ (c) family resources in terms of coping capabilities or ‘salutogenetic’ and regenerative variables of family life, and (d) differential aspects of family health, that is, differences between the developmental stages of the family life course, differences between family structures, and main results from gender-specific research.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Introduction

This research paper will first of all locate the topic of ‘family health’ within some main psychological traditions, before a systematization of the topic is proposed and selected empirical results are described briefly.

The field of family health can be seen at the crossroads between the disciplines of family psychology and health psychology. The connections between health and family factors are numerous, varied, and important. Nevertheless, the fields of ‘family health psychology’ and ‘family systems medicine’ are still in the early stages of development, although family psychology and health psychology are established disciplines (Akamatsu 1992).

Despite the fact that the family is the basic social context in which health behaviors are learned, clinical and health promotion theory and research traditionally have focused primarily on individual behavior. In contrast, family psychology has been studying interindividual relationships or ‘systems’ from its beginnings. Yet, within health psychology, family systems considerations are currently gaining recognition.

As health is a very important value for most individuals and families, it has always been of major interest within the discipline of family psychology, though not called ‘family health.’ Important contributions in research on family and health can be accredited to family stress research. In the beginning, this field of study focused on the familial crises brought about by major life events. At the same time, studies on the psychological processes of individuals were also ‘pathogenetically’ oriented. Antonovsky’s ‘salutogenetic’ approach offered an alternative to the pathogenetical perspective.

Antonovsky (1979) builds on earlier developments of Humanistic Psychology and the theory and practice of prevention, and he focuses on health-promoting factors and processes as well as on the characteristics of extremely healthy people or systems. In contrast to earlier studies on health and on the family, the current disciplines of family and health psychology are paying more and more attention to these salutogenetic views and models (see Olson and Stewart 1991).

The early notions of optimal family functioning were inferred from experiences with families or family members in treatment. As the practice of family therapy became institutionalized, integrative models of family health were developed increasingly. Generally speaking, theories and models of family psychology that can be regarded as unequivocally salutogenetic, either (a) conceptualize a health ideal of families, or (b) consider health processes within the context of individual or familiar resources that contribute to the state of health of the whole family or its individual members.

In the following sections, health is conceptualized as a state of total physical, psychological, and social wellbeing, and not only the absence of disease and disability (see Antonovsky 1979). As this definition contains a physical, a psychological, and a social component, it meets the requirements of a ‘biopsychosocial’ perspective in health psychology (see Schwarzer 1997).

Psychological definitions of family point out that a family is a special group of persons living in a close personal relationship, in the past, in the present, and in the future. It is an economic unit bound together by emotional ties (see Schneewind 1991).

In the following, the two topics of family and health are combined and a systematic overview of the field of ‘family health’ is offered.

2. Family Health: A Systematic Overview And Selected Empirical Results

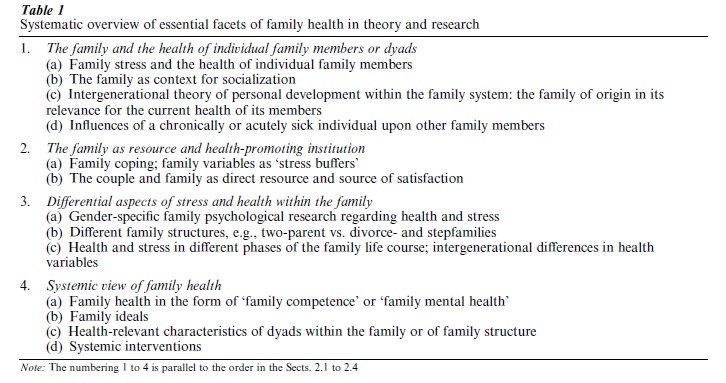

The very diversified subject of family health was dealt with by totally different directions in theory and research, such as stress research or feministic research. Following the systematic overview in Table 1, some of these different aspects of family health will now be described briefly.

2.1 The Family And The Health Of Single Family Members

Studying the links between family characteristics and the health of individuals, one has to distinguish whether (a) the effects of certain family characteristics or situations on system members are being considered, (b) the effects of certain individuals on the family, or whether (c) interaction processes and the resulting effects are being taken into account.

Effects of familial characteristics or situations are studied intensively by family stress research. Within this field, the family is viewed as a source of stress or a mediating factor. ‘Stress’ is considered either as ‘life events,’ family transitions, caregiving, or economic strains or stressors resulting from family interactions. Furthermore, extremely adverse familial influences such as violence and abuse are examined. All these forms of familial stress can affect psychological and physical health. Yet the extent of negative effects is highly dependent on coping processes and on individual and familial resources (see Sect. 2.2).

The study of familial influences on child development leads one into the very wide field of socialization within the family. Generally, the family is regarded as the main matrix of personality development, laying the foundations for mental health in childhood. From a clinical perspective, there are certain familial factors which put a child’s development at risk. Some of these risk factors are psychological disorders of a parent, parental delinquency, strong marital conflicts, and poor educational level of the parents. These variables have been found to correlate with emotional and behavioral disorders and academic failure during childhood. Moreover, childhood problems such as ‘internalizing disorders’ (e.g., depression) and ‘externalizing disorders’ (e.g., conduct problems) that stem in part from poor caregiving practices, are again strong predictors of mental disorders in adulthood.

What distinguishes effective from ineffective caregiving? Scientists have identified two fundamental dimensions of caregiving that are particularly important for children’s adjustment. The first is, how much warmth, nurturance, and acceptance (vs. hostility and rejection) caregivers convey to children. The second is how much control, structure, and involvement (vs. permissiveness and detachment) caregivers display towards their children. Schneewind and Ruppert (1998), for example, demonstrate by longitudinal data that the family’s atmosphere with the primary dimensions of positive emotionality, activation, and level of organization is a relevant predictor of family members’ emotional, personality, and social development as well as the child’s locus of control (see Schneewind 1995). Furthermore, studies have found that the family’s emotional expressiveness also plays a role in the development of social competence in children. Intergenerational family systems theory of personal development within the family views wellbeing within the context of a multigenerational model. The quality and dynamics of these significant relationship patterns are conceptualized as having far-reaching implications, not only for psychological functioning, but also for physical well-being, ability to cope with stress, and willingness to engage in positive health-related behavior. All of these assumptions are verified empirically. For practical reasons, nearly all of the studies rely on retrospective data, and most of them address only two generations. These studies, which consider the relationships between important psychological dimensions of the family of origin and the current health of family members, find, for example, moderate correlations between the degrees of autonomy and coherence, which were experienced by grownup members of their family of origin, and their current psychological adaptation. Studies on the role of parental separation and divorce for child development have shown evidence of impairments of a child’s social and personality development, mainly during the first year after the parent’s separation. But the effects measured have been proven to be minimal, and the differences between children of intact families and divorced families almost vanish as time goes by.

The study of effects of individual characteristics on the family has a theoretical tradition in the field of family therapy, despite the transactional thinking of this systems approach. In earlier family therapy theories, a family in which an individual member became schizophrenic or developed a psychosomatic illness was known as a ‘schizophrenic’ or ‘psychosomatic family.’ Virginia Satir’s experiential model of family therapy stresses the importance of the individual’s self-esteem to the family’s overall level of health. There are also empirical verifications of these interrelationships between self-esteem and perceived family functioning (e.g., Heaven et al. 1996).

This direction of effects from an individual’s state of health on the couple or familial relationship has also been examined in cases of acute or chronic illness of a child, a parent, or a spouse. Using longitudinal data, Booth and Johnson (1994), for example, demonstrated that health impairments of a spouse diminish the quality of the couple’s relationship quality, especially on the part of the sick person’s partner. Nevertheless, the couple’s or family’s coping processes are very relevant for the system’s adaptation to the situation.

2.2 The Family As A Resource And Health-Promoting Institution

Although the family and its patterns of interaction can be an enormous stressor, scientists also know about the positive and regenerative aspects of the family. These ‘family resources’ are fundamental for the functioning of every society. They include a large variety of aspects, ranging from material resources, over social support, dimensions of recovery, and familial coping competencies, to ‘daily uplifts’ within the family’s interaction.

An essential part of the health-promoting aspects of the family lies in the regenerative and protective effects of a good marriage or couple relationship (e.g., Gove et al. 1983). Even family status alone (single, married, separated, divorced, or widowed) shows significant connections with emotional well-being and life expectancy (e.g., see Cotten 1999, Gove et al. 1983). Despite a higher percentage of overweight persons among the married, living together with a spouse is on the whole health-promoting, especially for men. But these differences (between the groups and between the sexes) are diminishing currently. Furthermore, relationship quality is a moderating variable in the correlation between marital status and health, so that ‘good,’ satisfying marriages are more health-promoting (see Ross et al. 1990).

The correlation between socioeconomic status of families and mental and physical health appears consistently in the literature. Thus, the economic benefits within ‘dual-income’ families can be seen as a resource, as well as the emotional benefits which many women experience when they are working. These benefits could ‘buffer’ the stress of the ‘double burden.’

Individual stress research has shown that the way people cope with stressors such as critical ‘life events’ is even more important than their occurrence (e.g., see Antonovsky 1979). Furthermore, there is evidence that also on the family level the quality of coping (e.g., with acute or chronic illness), is extremely relevant. Is the family able to ‘buffer’ the potentially negative effects of the stressor, or does the family use dysfunctional strategies which only serve to worsen the situation? Adequate coping is a resource which can lead to the establishment of other resources, which then can be useful in comparable or totally different situations in the future.

For couples or parents, the emotional support of a spouse is evidently very important. Process analyses in the daily life of couples show that only in cases where a relatively high level of spouse support was evident does a decline in work-related stress occur during the evenings. Interestingly, allowing the partner to withdraw has proven to be one of the forms of spouse support (see Repetti 1989).

Furthermore, high quantity as well as quality of marital interactions has been connected with less risk-taking behaviors, such as less alcohol or drug use (see Wickrama et al. 1995). Similar findings regarding families demonstrate that the lifestyle of persons who live in families is more solid and healthier.

2.3 Differential Aspects Of Family Health

Especially in the case of traditional role sharing, we expect gender differences in the experiences of family life and—in relation to these differences—in health relevant variables.

Studies on the situation of the so-called ‘dual income’ families show that it is the women who experience a ‘double burden’ and difficulties in coordinating work and family life. In addition, for women the experienced inequality is more strongly connected with their couple satisfaction (see Kluwer et al. 1997). While women more often experience family stress in the form of their spouses’ behaviors (e.g., not enough support), men more often feel stressed by their partners’ criticism. Furthermore, as women tend to be supporting and do the larger portion of the household tasks, they have less time to ‘unwind’ after a stressful work day than their husbands (see Repetti 1989).

In summary, studies in Western nations have found that, although men show more risk-taking behavior compared to the more preventive behavior of women (Schwarzer 1997), women nevertheless have less favorable scores of physical and psychological health. This fact is to be seen in the context of the women’s work and family roles, and the overload that is so often connected with these (e.g., see Barnett and Marshall 1991). This strain from work, parental, and couple domains has negative effects on women’s well-being and health, and on the functioning of the family.

The lower health scores of older persons that were found by a large number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (e.g., see Schneewind and Ruppert 1998) can also be linked with family variables. Apart from biological factors, the stress of family transitions, such as disruptions of marital relationships through divorce or death, also bear aversive emotional and immunological consequences.

Another differential aspect of family health is the family structure or type. While it has often been thought that family structure (i.e., intact, divorced, stepfamily) was a key determinant of well-being, especially among children and adolescents, recent investigations have concluded that family process variables, such as conflict dynamics, cohesiveness, and support, are more important (e.g., Heaven et al. 1996; see above). Furthermore, cultural, social, and economic factors have widespread influences on the health of families.

Differential examinations of the different phases within the family life course show that the level of family stress is highest during the adolescent stage of family life, while family cohesiveness and satisfaction is lowest (see Aldous and Klein 1988).

2.4 Systemic View Of Family Health

Scientists who are dealing with an overall, systemic concept of family health try to meet the demands of the systemic approach. They look at the topic in a more holistic manner and identify the structures and processes of the ‘whole,’ the family system which is embedded in other contexts (e.g., society). Conceptions that consider the health of the whole family are, for instance, the psychological constructs of ‘family competence’ or ‘family mental health’ (e.g., see Pruchno et al. 1994), as well as all family ideals.

In terms of ‘family health’ measures, there are some self-report assessment instruments and additional measures which are designed to quantify the quality of familial functioning from the perspective of an external clinical observer. Questionnaires that consider an overall systemic construct, for example, ‘family mental health,’ usually found their operationalizations on sum scores of the individual family members as well as on discrepancy scores between them. Families with higher discrepancies in their perceptions of family reality normally have a lower score on individual wellbeing. Obviously, converging realities in the subjective views of the system members are functional, whereas larger divergences are a characteristic of clinical families.

Another concept which is of interest, not only from a systemic, family-centered perspective, but also from the perspective of health psychology, is the one of ‘family health cognitions’: but until now, the empirical basis regarding the impacts of family cognitions on the use of health services and on personal health actions is weak and needs further attention.

An example for a family ideal is the ‘balanced’ family type within the ‘Circumplex model’ (Olson 1989). These families have relatively high scores in cohesion (but without being ‘enmeshed’), and relatively high scores in their capability to adapt to new situations (without being ‘chaotic’). These characteristics are connected with better communication, more favorable coping, and higher family and personal satisfaction and health.

A further systemic perspective of family health concerns health-relevant characteristics of the system structure and the characteristics of dyads within the family system. Such a link between systemic–structural characteristics and family health is represented by the variables of generational boundaries and parental coalitions. Clear—yet not too rigid—boundaries be- tween the parental subsystem on the one hand and the children’s subsystem on the other have proven to be a characteristic of healthy family systems. Similarly, coalitions between the parents, the ‘architects of the family,’ are more functional than strong transgenerational coalitions (e.g., mother–daughter).

Furthermore, a systemic view of the whole family’s health is practiced in all family interventions, that is, in family-oriented prevention or health-promotion pro- grams and in family therapies. The insight that the health of the whole family should be considered when one member has a symptom was the birth of family therapy. Family health-promotion programs help families to sustain or enhance the social, emotional, and physical well-being of the family system or its members (see Schneewind 1991). These different kinds of family interventions have become well institutionalized. Nevertheless, researchers should pay more attention to evaluations of these different family interventions.

3. Conclusions

Family life experiences affect deeply the competence, resilience, and well-being of everyone. The family shapes the quality of our lives, but—to a certain extent—we also shape the quality and health of our families, especially when we become parents.

Research is paying closer attention to salutogenetic family-centered variables of coping and health. Empirical evidence supports this trend. Yet, in the field of research a great amount of work still lies ahead in order clearly to establish an overall systemic view of the family, whereas in the domain of family therapy this perspective has been the major characteristic from the very beginning.

As patterns of marriage and family life are currently changing in the Western world, scientists should be aware that changes in the strength of connections between family factors and health variables can occur. In the case of the association between family status and health variables, a decline in correlations has already been observed.

Although the family is the basic context in which health behaviors are learned, further research studies should well consider the interactions between the family and other social contexts, like peer or work relationships. Influences from the side of these other persons and systems could, for instance, be one possible explanation for the fact that until now studies have found only rather weak links between ‘family health cognitions’ and health-related behaviors.

All in all, knowledge of the frames for a healthy development from and in families is very relevant for different branches of psychology. The application of this knowledge is especially important for family interventions, such as prevention programs, but also for family politics.

Bibliography:

- Akamatsu T J 1992 Family health psychology: Defining a new subdiscipline. In: Akamatsu T J, Parris Stephens M A, Hobfoll S E, Crowther J H (eds.) Family Health Psychology. Hemisphere, Washington, DC, pp. 239–50

- Aldous J, Klein D M 1988 The linkages between family development and family stress. In: Klein D M, Aldous J (eds.) Social Stress and Family Development. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 3–19

- Antonovsky A 1979 Health, Stress and Coping. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Barnett R C, Marshall N L 1991 The relationship between women’s work and family roles and their subjective well-being and psychological distress. In: Frankenhaeuser M, Lundberg U, Chesney M (eds.) Women, Work and Health. Stress and Opportunities. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 111–36

- Booth A, Johnson D R 1994 Declining health and marital quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family 56: 218–23

- Cotten S R 1999 Marital status and mental health revisited: Examining the importance of risk factors and resources. Family Relations 48: 225–33

- Gove W R, Hughes M, Style C B 1983 Does marriage have positive effects on the psychological well-being of the individual? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24: 122–31

- Heaven P, Searight H R, Chastain J, Skitka L J 1996 The relationship between perceived family health and personality functioning among Australian adolescents. The American Journal of Family Therapy 24: 358–66

- Kluwer E S, Heesink J A M, van de Vliert F 1997 The marital dynamics of conflict over the division of labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family 59: 635–53

- Olson D H 1989 Circumplex model and family health. In: Ramsey C N Jr (ed.) Family Systems in Medicine. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 75–94

- Olson D H, Stewart K L 1991 Family systems and health behaviors. In: Schroeder H E (ed.) New Directions in Health Psychology Assessment. Hemisphere, New York, pp. 27–64

- Pruchno R, Burant C, Peters N D 1994 Family mental health: Marital and parent–child consensus as predictors. Journal of Marriage and the Family 56: 747–58

- Repetti R L 1989 Effects of daily workload on subsequent behavior during marital interaction: The roles of social withdrawal and spouse support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 651–9

- Ross C E, Mirowsky J, Goldsteen K 1990 The impact of the family on health: The decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family 52: 1059–78

- Satir V 1983 Conjoint Family Therapy. Science and Behavior Books, Palo Alto, CA

- Schneewind K A 1995 Impact of family processes on health beliefs. In: Bandura A (ed.) Self-efficacy in Changing Societies. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Schneewind K A 1991 Familienpsychologie (Family psychology), 2nd edn. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, Germany

- Schneewind K A, Ruppert S 1998 Personality and Family Development: An Intergenerational Longitudinal Comparison. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

- Schwarzer R (ed.) 1997 Gesundheitspsychologie. Ein Lehrbuch (Health Psychology: A Textbook) 2nd rev. edn. Hogrefe Verlag fur Psychologie, Gottingen, Germany

- Wickrama K A, Conger R D, Lorenz F O 1995 Work, marriage, lifestyle, and changes in men’s physical health. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 18: 97–111