Sample Childbearing Behavior Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

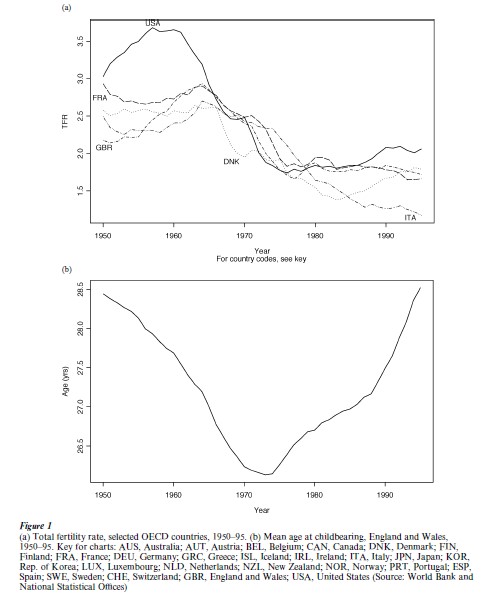

Childbearing takes place within the socially defined context of family life, but there have been substantial changes in family life in recent decades and it differs between societies and population subgroups. While childbearing patterns have also changed substantially in developed societies since the 1950s, there has been a tendency for trends to be broadly similar (Fig. 1(a)). The annual level of fertility in the post-1945 period rose to a peak around the late 1950 to mid-1960s, followed by a sharp decline in the 1970s and a slight rise and relative stabilization in the recent period, although some countries such as those in Southern Europe have continued to decline to levels of fertility just above one child per woman in the late 1990s (Coleman 1996). The average age at childbearing fell until the late 1960s or early 1980s and then rose substantially (Fig. 1(b)).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Annual levels and mean age at childbearing are closely related since a move towards earlier childbearing will increase the annual fertility rate even if the women having their children in that period do not ultimately have any more children by the end of their reproductive lifetime than other cohorts of women. Most of the large-scale movements in fertility in the postwar period are attributable to shifts in the age at childbearing rather that to changes in the overall propensity to have a given number of children: ‘most of the baby boom would have occurred without any change in the numbers of births per woman, and most of the decline since the baby boom as well’ (Ryder 1980, pp. 39–40). While the level of childbearing in a given year may reflect contemporary factors such as income or employment, some women may be having children then because they have postponed births from an earlier period or wish to bring their births forward for particular reasons. The fact that married women are much more likely to have a child than those not in a partnership, with cohabiting women generally in an intermediate position, means that earlier experiences of entry into and exit out of partnerships also need to be taken into account.

The main alternative theories that have been put forward to explain childbearing patterns will be reviewed briefly, before considering the extent to which they can be empirically validated.

1. Explanations Of Childbearing

1.1 Proximate Determinants Of Fertility

Fertility is often usefully analyzed in terms of a proximate determinants framework (Bongaarts and Potter 1983) which for developed countries means concentrating on three main factors; the proportion of women in a sexual union, their use of contraception, and the level of induced abortion. These factors biologically determine childbearing, but women’s choices about partnership and family limitation may also be consequences of their fertility decisions. One reason why women may enter a partnership is in order to have children, but it is unlikely to be the only one. On the other hand, use of contraception and abortion on ‘social’ grounds are determined by fertility preferences. Over time, there has been a change from a period when methods of family limitation were generally ineffective, difficult to obtain, and/or disapproved of, to one when methods are safe, easy to use, relatively inexpensive, reliable, and acceptable. This change occurred with the introduction of the contraceptive pill and IUD around 1960 in many developed countries, and the subsequent introduction of laws permitting abortion on wider grounds than previously. Studies in the US showed that the level of ‘unwanted’ fertility in the 1960s was about 0.5 of a child per woman (Westoff and Ryder 1977), similar to the difference in cohort fertility between women completing their childbearing at that time and today. The availability and acceptability of efficient contraceptive methods has had a major contribution to the change in timing which is the major determinant of overall period change. The effect of access to improved contraception not only affects childbearing, but permits couples to have a childless relationship (and, in particular, to facilitate the emergence of cohabiting relationships that have low rates of childbearing) and to decide on the pattern of childbearing with greater precision, since, for example, the possibility of an unwanted birth can be eliminated by contraceptive sterilisation. In turn, this has permitted the increase in mean age at childbearing and hence led to changing attitudes about women’s roles since a full satisfying sex life is now compatible with career progression by married women that would have been difficult in the past.

As improved access to methods of family limitation have increased across and within nations, variability in fertility has declined, so that the maximum difference in TFR levels between the OECD member countries in 1995 was 0.9 of a child, compared with a value of 1.9 in 1965 and 1.8 in 1980.

1.2 Economic Approaches

In the past, a positive relationship between fertility and income (in cross-section) and with the business cycle (in time trend) had been accepted. However, in the period since 1945, fertility and real incomes generally have been negatively rather than positively related in developed countries, since fertility is now at an all time low, whereas average real incomes have risen. The current widely used microeconomic model of fertility is the ‘new home economics’ one particularly associated with the work of Becker (1981) that has been extended to both marriage and marital breakdown.

The model brought together two features within the framework of microeconomic analysis to account for the postwar baby boom and bust: the first was the increasing importance of women’s work outside the home and its competition with childrearing for the wife’s time. Since women undertake the greater burden of childrearing, the costs of childbearing, especially in terms of earnings foregone while they are looking after children and future labor market prospects, fall most heavily on them. Therefore, the number of children is expected to be strongly negatively related to her earnings, but weakly positively related to her husband’s earnings, and the opportunity costs of childbearing are greatest for women in highly paid jobs.

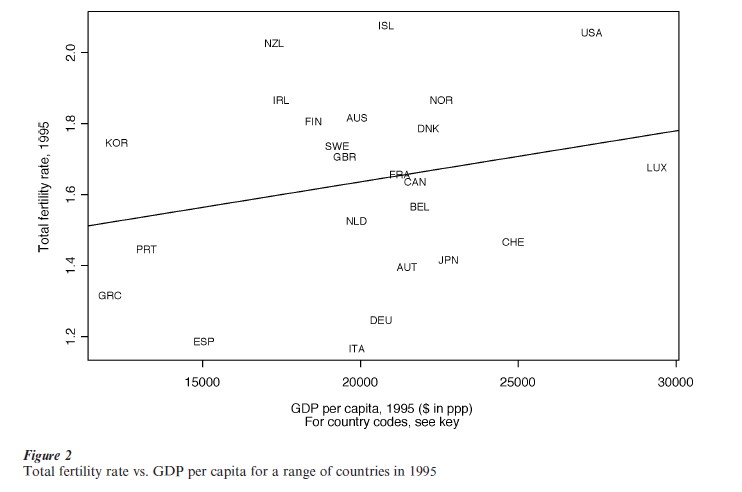

The second element, the demand for children, is determined in part by economic factors and in part by ‘tastes’ which may differ by religion, race, age, and time period, etc. Decisions concerning childbearing have two major components, those related to quantity and ‘quality’: ‘quality’ is simply measured by the amount spent on a child on items such as clothing, education, etc. (‘higher quality’ does not mean superior, just more expensive). Thus, parents can choose higher ‘quality’ of a lower quantity of children for a given level of overall expenditure. It is assumed that increased income will be diverted more towards increases in quality rather than quantity, and it is possible that if the shift towards higher quality is so substantial, increased income may result in fewer children. At present, the cross-national relationship between average income and fertility is positive but weak in developed countries (Fig. 2).

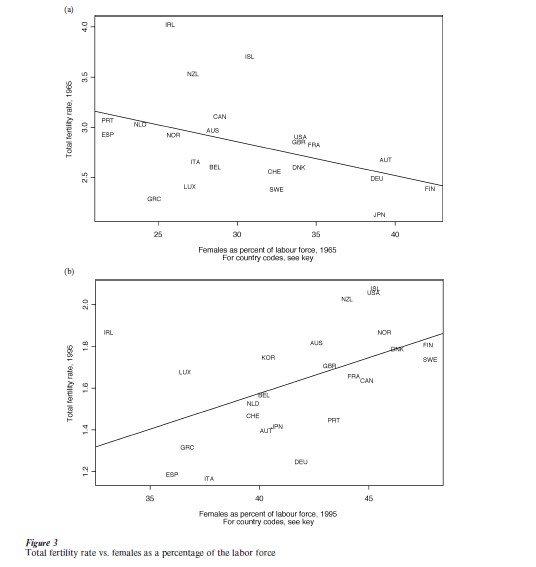

The relationship between female employment and fertility is expected to be more clearly negative since a basic incompatibility between work outside the home and childrearing is assumed as they are competing demands for the mother’s fixed amount of available time. (This approach has been criticized on the grounds that it emphasises the differentiation of gender roles: however, since it reflects how things are, rather than how many think that things ought to be, such criticisms are unfair.) While in the 1960s, there was the expected negative relationship between female employment and fertility across countries, by the 1990s, the relationship had become positive (Fig. 3). In the 1990s, Scandinavian countries have relatively high fertility and female employment, while Mediterranean ones score low on both counts, whereas although the female employment rankings have remained relatively constant since the 1960s, the fertility ones have reversed. Of course, such simple correlations do not establish that the nature of the relationship has switched over time, but it is clear that the other factors that cause the correlation to be in the unexpected direction in the 1990s must also have a very substantial, if not dominant, effect on childbearing.

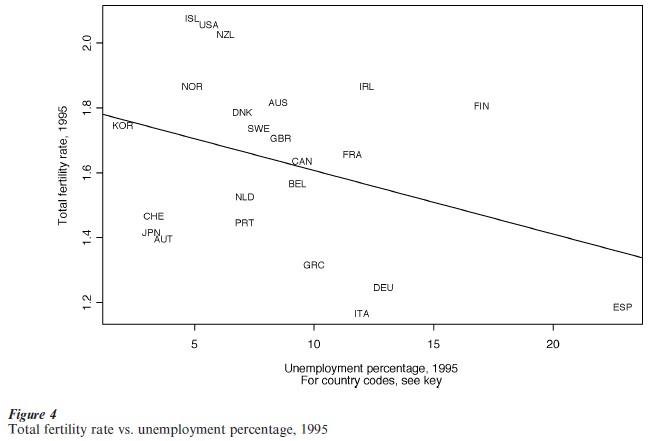

An alternative economic-demographic model is that of Easterlin (1980). In simplified form, it assumes that individuals’ (or couples’) expectations are set by the standard of living in the home that they had as children. Those born into large birth cohorts will have many direct competitors for education, employment, housing, etc., and are likely to be relatively disadvantaged compared with those from smaller cohorts and they will react by marrying later and having fewer children. There is little empirical evidence that large cohorts are disadvantaged and earnings are more likely to be associated with other period and structural factors. This model emphasis men’s as well as women’s employment situations, but because it appeared to have little explanatory power, the role of male employment has tended to be neglected compared to that of women. However, the declining position of men relative to women in the labor market, and, in particular, the rise in unemployment that particularly affected young men is likely to inhibit leaving home and partnership formation, as well as making young men less attractive lifetime partners to young women (Oppenheimer 1994). Such considerations may be especially important among disadvantaged groups such as young black males in developed countries. Overall, there is a negative relationship between unemployment and fertility in the OECD countries (Fig. 4). Although the unemployed are disproportionately drawn from groups that would in any case be expected to start childbearing early and for this reason, among others, may have higher fertility than those in employment, a high level of unemployment is likely to have the effect of inhibiting partnership formation and childbearing of those in employment.

1.3 ‘Cultural’ Explanations

In a study of the determinants of fertility decline in European historical and contemporary Third World countries, Cleland and Wilson (1987) concluded that ‘economic’ theories are much less successful than ‘cultural’ explanations. For example, fertility change was more closely associated with factors such as language and voting patterns than with income or employment (Coale and Watkins 1986).

Attitudes to increased sex role egalitarianism, and permissiveness to divorce and cohabitation have become more positive over time, whereas attitudes to religion, traditional family orientation, and deference to authority have declined. These changes are associated with a move towards greater individualism that has been associated with a range of emerging patterns of family formation and dissolution often referred to as a ‘Second Demographic Transition,’ based on individual autonomy, female emancipation, and in-creased consumerism (van de Kaa 1987, Lesthaeghe 1995). Such approaches integrate the interaction of different life events such as partnership, childbearing, and employment within the historical context, both national and individual, including cohort effects.

2. Assessing The Empirical Validity Of Alternative Explanations

While swings in annual levels of childbearing have attracted much comment, especially the very sharp and largely unanticipated change between the late 1950s and 1970s, from a long-term perspective, it is the baby-boom period that stands out as the anomaly as fertility has shown a generally declining trend for over a century in many developed countries. In the 1950s the main alternative to remaining at home with one’s parents was early marriage (sometimes precipitated by pregnancy), followed by a relatively quick start to childbearing, both because this was expected and the possibilities of delaying births were limited. The relatively high level of fertility at that period reflects the selection by women of a package of husband/home/children rather than solitude/parental residence/work. In addition, couples expected that the marriage would last and that employment would be permanent, so increasing the attractiveness of marriage. More recently, people have had the opportunity of childbearing without partnership and vice versa, and other options such as living alone have become more feasible. Therefore, the nature of the choices made with respect to childbearing have changed substantially over time, which complicates the specification of appropriate empirical models.

There are many levels at which analysis and interpretation may be undertaken: international comparisons; subpopulations within nations; families households; individuals; and, most generally, combinations of data from different levels. Childbearing is clearly sensitive to short-term factors such as pill scares, which may therefore provide good short-term explanations of fertility change (Murphy 1993). However, establishing the reasons for the long-term changes shown in Fig. 1(a) is more difficult. Some of the most widely cited studies for empirical underpinning of the theory have been based on the macrolevel time-series studies of the effects of income on fertility in developed societies. The problem in using aggregate-level data to draw conclusions about individuallevel behavior is widely recognized.

A rational choice model underpins most discussion of childbearing, although this is often less helpful than might be thought since the number of factors that enter into the choice are very broad in both time and space. Childbearing is likely to have substantial effects on the emotional, lifestyle, and financial circumstance of the mother for at least two decades, and for most fathers too. Over time, the balance of advantage will have changed considerably. Some of these aspects may be much easier to measure than others. For example, higher social benefits for unmarried mothers which are relatively easy to measure, would be expected to lead to more births outside marriage, but a more important factor could be a reduction in public disapproval for such childbearing, and the availability of benefits a consequence of changing public attitudes, which may be difficult or impossible to quantify especially if no contemporary data exist.

It may be useful to make a distinction between those factors that have an unambiguous effect on childbearing and those for which the effect is likely to be context-specific. For example, it has been assumed that the effect of women’s work outside the home is to reduce their fertility, as seen in the 1960s in Fig. 3(b). However, by the 1990s, the reverse was the case in that those countries with high rates of female employment had higher fertility also. The range of reasons for this could include:

(a) formerly it was considered inappropriate for women with young children to be in paid employment, whereas now it is not considered harmful to the child (social influence);

(b) to bring up a child, two incomes are now required whereas one would suffice in the past (reversed female income effect);

(c) improved childcare facilities and technology makes it more feasible to combine childrearing and work than in the past (institutional and technological change);

(d) withdrawal from the labor force for childrearing could have harmful long-term economic and career prospects for women, especially in societies with high rates of marital breakdown (external demographic effect);

(e) societies that have low female employment have high unemployment and poor job security that inhibits family formation (historical macroeconomic factor);

(f ) societies that have exhibited substantial fertility declines recently may reflect reduced fertility by older women who have sufficient children and postponement by younger women (transitory effect).

This list is not exhaustive but serves to emphasise the difficulty in establishing empirically the nature of the relationship between childbearing and the single variable of female employment. The statement that if increases in paid work outside them by women of childbearing age makes bringing up children less attractive as an option, with other things being constant, then childbearing will fall is uncontentious. However, these other relevant factors that are not constant may be moving and be the dominant determinants of change. The dependent variable in the new home economics model is not number of children born, but it is the benefits obtained from their children, yet this cannot be clearly specified and so number of children is often used as the variable to be explained. The biological, cultural, institutional, economic, and historical factors that influence childbearing decisions are complex and it is impossible to obtain comparable data on these different domains, so in practice, it is almost impossible to specify a comprehensive formal model to ‘explain’ contemporary patterns. It is, therefore, unsurprising that after many decades of investigation, although a number of valuable insights have been made about the determinants of childbearing trends and differentials between subpopulations, full explanations remain elusive.

Bibliography:

- Becker G S 1981 A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Bongaarts J, Potter R G 1983 Fertility, Biology and Behavior. Academic Press, New York

- Cleland J, Wilson C 1987 Demand theories of the fertility transition: An iconoclastic view. Population Studies – J. Demog. 41: 5–30

- Coale A J, Watkins S C (eds.) 1986 The Decline of Fertility in Europe. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Coleman D (ed.) 1996 Europe’s Population in the 1990s. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Easterlin R A 1980 Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal Welfare. Basic Books, New York

- van de Kaa D J 1987 Europe’s Second Demographic Transition. Population Bulletin 42: 1

- Lesthaeghe R 1995 The second demographic transition in western countries: An interpretation. In: Oppenheimer Mason K, Jensen A-M (eds.) Gender and Family Change in De eloped Societies. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 17–62

- Murphy M 1993 The contraceptive pill and women’s employment as factors in fertility change in Britain 1963–1980: A challenge to the conventional view. Population Studies – J. Demog. 47: 221–43

- Oppenheimer V K 1994 Women’s rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review 20: 293–342

- Ryder N B 1980 Components of temporal variations in American fertility. In: Hiorns R W (ed.) Demographic Patterns in Developed Societies. Taylor & Francis, London, pp. 15–54

- Westoff C F, Ryder N B 1977 The Contraceptive Revolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ