Sample Economics Of Intergenerational Relations Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

In economics, the term ‘transfer’ is used to refer to the delivery of money or other assets, without counterpart. We do not talk of transfers, therefore, in the context of a commercial transaction, where money is the counterpart of goods or services. Public transfers, by contrast, are the direct subsidies that governments pay to households and firms. Although such subsidies are financed out of tax receipts, there is in fact no direct link between what any particular firm or household pays in taxes, and what it gets back in subsidies. A gray area is represented by certain types of old-age pensions, where the size of the benefit is related in some way to contributions made, but the rules on the basis of which the calculation is made are subject to change by political decision.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

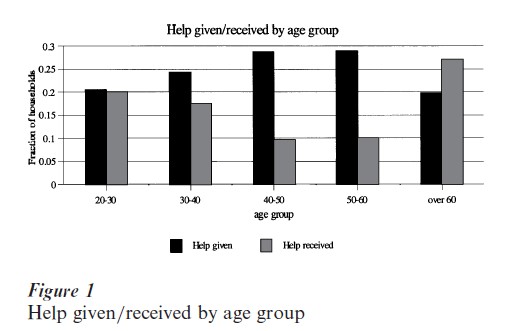

Transfers between generations may be voluntary, or forced by the tax system. Here, we are concerned with voluntary transfers between different generations of the same family, but we are also interested in how these respond to public transfers. Typically, the latter redistribute income away from working-age cohorts, who pay more taxes and receive less subsidies than younger and older cohorts. A similar age pattern applies to voluntary inter i os transfers: Fig. 1, drawn from Cigno and Rosati (2000), shows the distribution, by age of the household head, of monetary help to and from non-coresident ‘friends or relatives’ (overwhelmingly relatives) by Italian households during the late 1980s. It transpires that the probability of making a transfer is highest, and that of receiving one lowest, when the household head is in the 40–59 age range. Similar pictures can be constructed for other countries. What can be the reason for such a pattern?

Economic explanations fall into two broad categories. One follows what is called the altruistic approach, whereby individuals are assumed to derive direct utility (satisfaction) from the wellbeing of other family members. The other assumes that individuals are ultimately self-interested. Transfers are straight, no-strings-attached gifts according to the first of these explanations, part of a strategy that is expected to bring, directly or indirectly, benefits to the donor according to the second.

1. Altruistic Explanations

Simple altruistic explanations assume that sentiment is unidirectional: either from parents to children (descending altruism) or from children to parents (ascending altruism). More complicated versions allow for altruism in both directions.

Descending altruism underlies Richard Barro’s and Gary Becker’s theories of voluntary transfers. This assumption allows them to model transfers within the family as the outcome of a single optimization, whereby parents decide how much each family member will consume, subject to two constraints. One is that the sum of the consumption expenditures of all family members cannot exceed the sum of their incomes. The other is that transfers received (the difference between consumption expenditure and income) by any family member other than the decision-maker(s) must be positive or zero, otherwise they would be rejected. Under standard conditions, the model predicts that transfers will not decrease (increase) as the income of the donor (beneficiary) increases. This is consistent with the observation (Fig. 1) that the probability of making a transfer is highest, and that of receiving one lowest, in middle age, when incomes are generally at their peak. It is difficult to reconcile, however, with the observation that people continue to receive inter vivos transfers after the age of 60 (or even 75), when few of them have living parents.

If it is assumed that parents make transfers in the form of bequests, rather than inter vivos, the descending-altruism model predicts that household saving is increased, dollar for dollar, by any current government deficit (Barro 1974). That is because, conscious of the government intertemporal budget constraint, altruistic taxpayers perceive any current deficit as a tax on their descendants (this is the so-called Ricardian equivalence, from the name of David Ricardo, who first detected it). According to the model, taxpayers thus respond to a government deficit by saving more, in order to be able to leave their descendants bequests large enough to pay the extra taxes. One of the mechanisms that might generate such a deficit is a pay-as-you-go public pension system, where current pensions are paid out of current contributions. Whichever the mechanism, however, any net public transfer will be matched by private transfers of opposite sign.

Ricardian equivalence does not hold if fertility is endogenous i.e., if parents can choose how many children to have (or, more realistically, condition the probability distribution of births), and parents derive satisfaction from the number of children, as well as from how much each of them consumes (Becker and Barro 1988). Suppose, then, that the government were to take a dollar off the social security contributions due by each of the present workers, without any corresponding reduction in their pension entitlements. Each member of the next generation would then have to pay (r/n) more dollars in taxes, where r is the intergenerational interest factor, and n the ratio of future to current taxpayers (roughly, the population growth factor). Knowing that, present workers would then want to compensate their own children by making larger bequests to each of them. But this would make it more expensive to have an extra child relative to increasing the wellbeing of existing children. Under standard conditions, the present generation would then choose to have fewer children, and to more than compensate each child for the heavier tax burden he or she will have to shoulder. Of course, the change in fertility behavior would result in a lower n, and thus raise the burden on each future taxpayer, but the effect of each couple’s actions on the aggregate fertility rate is infinitesimal. Couples, therefore, will not take this effect into account when they decide how many children to have. Hence, fertility would fall. Saving could rise or fall, depending on whether the rise in transfers per child is proportionally larger or smaller than the reduction in the number of children. By contrast, if the government were to promise higher benefits to current taxpayers already covered by oldage security, or extend coverage to new categories, and simultaneously raise taxes or contributions so as not to force a transfer in favor of present workers, there would be no effect on either saving or fertility behaviour. There is evidence (Cigno and Rosati 1996, among others) that old-age security per se (i.e., without intergenerational spillovers) encourages household saving and discourages fertility, while deficits discourage saving. This empirical finding is consistent with the Becker–Barro prediction that a deficit could result in lower savings, but contradicts that model’s prediction that, in the absence of intergenerational transfers, saving and fertility would remain the same.

The implications of ascending altruism (Nishimura and Zhang 1992) are somewhat different. The direction of transfers is not from working-age parents to young children, as in the case of descending altruism, but from working-age children to retirement-age parents. This is consistent with the observation that old people receive inter vivos transfers, but difficult to reconcile with the one that they also make such transfers. As children are a source of income, parents treat them as an asset. If fertility is endogenous, working-age individuals (or couples) then choose the composition of their portfolios so as to equate the marginal return to having children to that of holding conventional assets (capital). According to this model, a gift to current tax payers at the expense of future ones would induce parents to save more, not in order to leave larger bequests, but in order to put some of the windfall aside for old age. By contrast, a fully funded expansion in pension coverage (a form of forced saving) would reduce voluntary saving. These predictions clash, however, with the empirical finding, already mentioned, that deficits discourage voluntary household saving, while social security coverage per se has the opposite effect.

Whichever the direction, unilateral altruism is thus an inadequate explanation of what we observe. Can bilateral altruism (parents love children, children love parents) do better? If family members are unanimous in their preferences, intrafamily transfers can again be described as the outcome of the maximization of a single preference function (this time agreed upon by all family members), subject only to the constraint that the sum of the expenditures cannot be greater than the sum of the incomes of all family members. There is now no restriction on the direction of money flows: de- pending on life-cycle patterns, transfers from middleaged children to elderly parents may be positive in some families and negative in others. This is consistent with evidence of two-way flows between generations, but the model also has a stronger behavioral implication: since the amount consumed by each family member depends on total family income, and not on his or her own individual income, changing the intrafamily distribution of income should not change the intrafamily distribution of consumption. Statistical tests based on this property of the model (Cox 1987, Altonji et al. 1992) reject the hypothesis of altruism. That property also has the strong implication that redistributive policies are ineffective: taking a dollar off the rich (the parents) and giving it to the poor (the children) would reduce the amount voluntarily transferred from the former to the latter by exactly one dollar.

In general, however, different family members are likely to have different ideas about the most desirable pattern of transfers. Even if all family members were altruistic towards one another, each of them might in fact appreciate his or her own consumption a little more (or, for that matter, a little less) than another family member. If that is the case, transfers cannot be viewed as the solution to a single optimization. They must rather be seen as the outcome of a game (in the sense of formal game theory) in which family members bargain with one another, or respond strategically to one another’s moves, pretty much as if they were pursuing purely selfish aims (Manser and Brown 1980, Stark 1993). In such a situation, transfers depend on individual fall-back positions (what the player would get, if he or she dropped out of the game), as well as on preferences and characteristics. It is then difficult to distinguish empirically (McElroy 1990) bilateral altruism from self-interest, to which we now turn.

2. Non-Altruistic Explanations

Non-altruistic explanations are based on the assumption that individuals are interested only in their own lifetime consumption stream. If a person voluntarily surrenders money to another, it will be for profit, or in order to improve the allocation of consumption over the life-cycle, or across states of the world. It must also be true that the person in question could not get a better deal from the market. There does not seem to be any difference of substance, therefore, between this and giving money to the grocer in exchange for a dozen eggs. Nonetheless, it is customary, maybe due to lack of information, to classify as transfers any moneys changing hands within the family whenever there is no explicit quid pro quo (not, however, in the case of a father paying his child to wash his car).

Mutual insurance (‘I help you if things go well for me and badly for you, you help me if it is the other way round’) is a typical form of intrafamily arrangement. But why should people want to enter into such informal, maybe even tacit, agreements, if it is possible to buy insurance from the market with all the safeguards afforded by the law? The insurance market has the advantage over the family that individual risks are less likely to be correlated in a large heterogeneous population than in a small homogeneous group. Because of adverse selection and moral hazard problems, however, the market might not offer insurance, or offer it on very unfavorable terms, to certain individuals or for certain types of risk. Such problems are generally less acute within the family, the members of which have privileged information on one another’s characteristics, and lower costs of monitoring one another’s behavior. In some circumstances, it may thus turn out that intrafamily arrangements are more advantageous than market insurance, or that there is no alternative.

Mutual insurance may or may not result in intergenerational transfers (not if the agreement is among contemporaries). Intergenerational transfers, by contrast, are essentially another kind of insurance arrangement whereby a person (parent) transfers wealth or pre-commits to leave a bequest to a younger relative (child) in exchange for a promise of indefinite old-age support, effectively in exchange for an annuity (Kotlikoff and Spivak 1981). That way, the parent buys insurance from the child against the risk of running out of money after too long a period of retirement.

Another type of mutually advantageous intrafamily deal, also giving rise to intergenerational transfers, stems from life-cycle income variations and capital market imperfections. Standard microeconomic theory predicts that individuals smooth consumption over the life-cycle by borrowing from the market when they are young, and lending (buying assets) when they are middle-aged. In reality, however, minors cannot sign contracts, and young adults have difficulty in obtaining credit against future earnings. The very fact that people survive to adulthood is thus evidence that the young receive support in other ways, but from whom? We have just seen that nobody makes genuine presents. Self-interested relatives, on the other hand, will make loans, not presents, and only if the risk adjusted return is at least as high as that offered by the formal capital market. And what is there to induce a selfish adult to honor an informal debt incurred 20 or so years earlier?

Imagine a set of family rules (family constitution) prescribing the amount that a parent must pay a young child, and the amount that a grown-up child must pay an elderly parent, subject to the clause that nothing is due to a parent who disobeyed the rules. Such a constitution is self-enforcing, in the sense that it is in everybody’s interest to comply, if the rules are so designed that complying with them is at least as advantageous, for a middle-aged person, as the alternative strategy of having no children, giving nothing to parents, and providing for old age by buying capital (Cigno 1993). This line of reasoning explains transfers to the young as implicit loans, and transfers to the old as implicit loan repayments. In such a situation, paying back one’s own parents is a condition for getting the same treatment from one’s own children. Now suppose that the level of old-age security is raised, or coverage extended to new categories. The present middle-aged affected by the policy will then want to shift less of their current spending capacity to old age. Since the amount they are supposed to pay to their elderly parents has not changed, however, some of these middle-aged persons will find it advantageous to disobey the constitution, and consequently give up the idea of being supported by their own children in old age. They will then default on their implicit debt towards their own parents, have no children, and possibly top up their expected pensions by buying assets. Conversely, if the government were to cut current taxes or social security contributions without reducing pension entitlements, some middle-aged individuals, who would otherwise have found it advantageous to buy assets, would have children instead. This is consistent with the already mentioned empirical evidence that aggregate household saving responds positively to old-age security, and negatively to deficits. It also explains why fertility responds negatively to old-age security.

Bibliography:

- Altonji J G, Hayashi F, Kotlikoff L J 1992 Is the extended family altruistically linked? Direct evidence using micro data. American Economic Review 82: 1177–98

- Barro R J 1974 Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy 82: 1095–1118

- Becker G S 1974 A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy 82: 1063–93

- Becker G S, Barro R J 1988 A reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Quarterly Journal of Economics 103: 1–26

- Cigno A 1993 Intergenerational transfers without altruism: Family, market and state. European Journal of Political Economy 7: 505–18

- Cigno A, Rosati F C 1996 Jointly determined saving and fertility behaviour: Theory, and evidence for Germany, Italy, UK and USA. European Economic Review 40: 1561–89

- Cigno A, Rosati F C 2000 Mutual interest, self-enforcing constitutions and apparent generosity. In: Gerard-Veret L A, Kolm S C, Mercier-Ythier J (eds.) The Economics of Reciprocity, Giving and Altruism. Macmillan, London

- Cox D 1987 Motives for private income transfers. Journal of Political Economy 95: 508–46

- Kotlikoff L J, Spivak A 1981 The family as an incomplete annuities market. Journal of Political Economy 89: 372–91

- Manser M, Brown M 1980 Marriage and household decision making. International Economic Review 21: 31–44

- McElroy M B 1990 The empirical content of Nash bargained household behavior. Journal of Human Resources 25: 559–83

- Nishimura K, Zhang J 1992 Pay-as-you-go public pensions with endogenous fertility. Journal of Public Economics 48: 239–58

- Stark O 1993 Nonmarket transfers and altruism. European Economic Review 37: 1413–24