Sample Health Care Marketplace in the US Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

As the twenty-ffirst century begins, the U.S. health care system has endured a turbulent, unremitting change cycle for over two decades. It is truly a system in motion, configuring and reconfiguring itself on a regular basis in response to the forces fueling change. The genesis of this turmoil has been the efforts for economic reform on the part of both business and government, motivated by the desire to reduce health care costs. The health care system has been restructured around free-market principles, and there has been a dramatic shift in the way health care services are organized, delivered, and financed. In the past, health care was seen as a profession in which professional authority held sway.Today it has been transformed into a marketplace, where it is being treated like other commodities. Behavioral health care, as part of the larger system, has also experienced change, notably in the way it is financed and in its unfortunate segmentation from medical and surgical care. Practicing psychologists are in a very different health care world than existed through the mid-1980s.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In many other countries in the world, health care is centralized, with the government both financing and paying for the care. This is not the case in the United States, which has not adopted such a single-payer system. The way health care is financed in this country lies at the heart of the problems that the system faces today. The consumer (the patient) does not pay for most of the expenses associated with an episode of care. Rather, either the patient’s employer or a governmental agency bears the costs. The arrangement is called a third-party payer system, and health care in the United States is completely dependent on it. Almost four out of every five dollars flowing into and supporting the health care enterprise come not from the consumer, but from either the government or employers. Medicare, Medicaid, and other local- and stategovernment-sponsored programs pay 47% of the nation’s health care bills. Group health plans funded by employers as part of benefit packages pay 32% of the total cost (VHA Inc., Deloitte, & Touche, 2000).

Beginning in the 1970s, health care costs began to increase dramatically, a trend that would continue into the mid-1980s. At that time, businesses started to feel the strain on their profits and began to exert pressure on health plan administrators to contain costs.They were joined in this effort by State and Federal governments eager to avoid tax increases. The concerted efforts of government and industry to contain costs through various mechanisms have provided the impetus for economic reform in health care. Cost containment has not proven an easy goal to achieve, however, because of a number of factors. First of all, medical practitioners have been reluctant to change from a system of finance in which they dominated. From the late 1930s to the 1980s, the standard method of reimbursing providers and service facilities was the fee-forservice/third-party Payer system (FFS/TPP).This system was built on provider-oriented principles that considered medical practitioners to be members of a protected guild, similar to medieval guilds. It virtually eliminated price competition as a cost-containment mechanism and prevented free enterprise marketplace forces from operating naturally in the health care system. A further impediment to cost containment is the fact that the primary purchaser (employer or government) is not the recipient of the care. In the FFS era, not only did patients not pay for care directly, but also they were largely unaware of the true costs of the care received. Physicians themselves often remained uninformed about costs. Finally, it must be observed that change does not come easy in any enterprise grounded on the ethical principle that both life and quality of life are precious. Legitimate concerns that efforts to contain costs will lead to deterioration in quality of care abound in the health care marketplace today.

However difficult it has proven to contain costs, the efforts to do so by purchasers have led to dramatic changes. An entirely new health care environment has been created, one with serious implications for all health care stakeholders. Purchasers ceased accepting the cost increases of the FFS system and became active promoters of price competition via a competitive bidding process. They no longer favor purchasing traditional indemnity or service insurance coverage; where permissible, they self-insure, either passing on financial risk or engaging in shared financial risk arrangements with health plans. Health plans now find themselves in a difficult situation. They promised purchasers that they could reduce expenditures while retaining and even improving quality of care. This has proved daunting, to say the least, because purchasers have continued to cut funding—although expecting health plans to deliver the same level of quality. Purchasers are asking their employees to participate in the cost-containment effort. Employers no longer advocate for employees. They now support efforts by health plans to reduce expenditures. They attempt to increase employee cost sensitivity by forcing higher contributions to premium charges and supporting higher copay, coinsurance, and deductibles.

Because the hallmark of the health care environment today is rapid change and because stakeholder roles and relationships are not in stable alignment, a purely descriptive approach to the health care marketplace would have a short shelf life. In this research paper, therefore, the focus is on understanding the forces driving change, including marketplace dynamics. To build a foundation, the paper begins with a discussion of the primary stakeholders in health care, followed by a brief explanation of how two categories of forces, sustaining and disruptive, are able to shape a marketplace. Next are described the three distinct eras in health care from the late 1880s to the present: (a) the self-regulatory era, (b) the FFS/TPP era, and (c) the present-day cost containment era. During the first and second periods, stakeholder revolts against the prevailing system ultimately ushered in the next era, establishing the principles by which it would function. The market and service delivery features of the FFS/TPP era are described in detail because they became the health care standard against which the stakeholders of the current cost-containment era are now in revolt. The current revolt seeks to replace the cost-increasing, noncompetitive features of the FFS/TPP system with market-based, price-competition approaches. During the current era, a number of disruptive innovations altered important features of the FFS/TPP system, and these are discussed. Next, the impact of the cost-containment era on health care stakeholders is analyzed, with an emphasis on how health care is financed and delivered, in particular behavioral health care. The dynamics of health care that continue to create a changing environment are explained, and the paper examines some future trends.

Stakeholders and Their Strategies

Marketplace dynamics operate continuously in the health care arena. All free markets have stakeholder groups, which are either part of the supply or part of the demand side of the market. The various stakeholders vie for supremacy, attempting to promote their own interests by modifying the market to achieve their particular economic goals. The stakeholders are often the instigators of two categories of change forces: sustaining forces and disruptive forces. Both types of change forces are capable of altering the marketplace dynamics, and the various stakeholders can and do employ them to further their own goals. The interplay and competition among stakeholders in the health care marketplace has driven change for over a century.

The Four Stakeholders

The four key health care stakeholder constituencies in the United States are (a) purchasers, (b) health plans, (c) providers, and (d) consumers. The purchasers are largely the employers who pay health plan premiums for employees; alternatively, they represent governmental agencies that pay for health care costs for enrollees in their programs. The various state and federal governmental entities also serve as the regulators of health care. Through antitrust enforcement, national and state rule-making authority, and legislative actions, governmental power takes a large role in shaping and defining the health care system in the United States. Health plans typically define and administer the benefit system used by the consumer and contract with providers and their service facilities (particularly hospitals) to provide health care services for enrollees. Using a variety of insurance or financial arrangements, health plans contract with purchasers who pay premiums on behalf of employees or, in the case of governmental entities, on behalf of beneficiaries. The provider stakeholder constituency consists of the clinicians who provide care (physicians, psychologists, physical therapists, nurses, etc.) and the service facilities in which care is provided. Consumers, the largest stakeholder constituency, include the patients who receive care and the families affected by the nature and quality of the care provided.

Forces for Change: Sustaining and Disruptive Innovations

Even given the imperative for reduced health benefit expenditures stimulated by health care purchasers, change of the magnitude being experienced in the health care marketplace could not occur without additional powerful forces disrupting the status quo. Christensen, Bohmer, and Kenagy (2000) described two categories of change forces that have altered the way free markets operate and evolve. Sustaining innovations represent advancements that move technology forward, extend or expand capability, or improve precision. Health care examples include discovering the importance of antiseptics in preventing infection during treatment, developing antibacterial agents, improving imaging of internal body systems, and finding treatments for previously untreatable conditions. Sustaining innovations typically extend or enhance the prevailing technological or business paradigm and thus expand the market. The second category of change forces is disruptive innovations. Because they significantly transform the prevailing business or technical paradigm, disruptive innovations create more turbulence than do sustaining innovations and therefore are more difficult for stakeholders in the marketplace to incorporate to their advantage. Disruptive innovations are usually adopted when they decrease the cost of a product or service for the majority of the market by introducing new, more effective technology or business models. Disruptive innovations make it possible for services to be provided with equal effectiveness for less cost.

About 25 years ago the health care system began to be bombarded by disruptive innovations aimed at changing the prevailing paradigms for finance and service delivery. These innovations are linked to a specific category of stakeholders: the purchasers. Normally, disruptive innovations in free markets have direct, apparent benefits or appeal to the true consumer of the product or service.The benefits resulting from these recent disruptive innovations in health care have accrued more to the purchaser, however. Change is not being driven directly by consumer needs, and it has complicated the change process.The actual consumer of health care has had to adjust to alterations that in many cases have led to increased out-of-pocket expenses, have disrupted relationships with providers, or have created more complicated rules regarding access to care. With the stakeholders in mind and an understanding of the change forces operating in the marketplace, it is time to examine the evolution of health care from the late nineteenth century through the current period.

Evolution of Health Care in the United States

Current health care in the United States, including its service delivery and finance systems, stems from an evolutionary process that began in the late nineteenth century. Over the last 120 years, certain key historical actions have defined how health care coverage is obtained, how services are financed, and how competition and choice operate in the health care marketplace. It is possible to divide health care in the United States into three eras, employing a framework similar to Weller (1984; for a more detailed description of the social, political, and economic factors at work in transforming the health care system up through approximately 1980, see Starr, 1982, and Weller, 1984). In the self-regulatory era of the late nineteenth century, a free-market environment for health care was operating and evolving in response to the economic and social conditions of the time. This era ended as a result of actions taken by a particular stakeholder constituency: the provider, representing the interests of physicians and hospitals. In the 1930s a new era was launched, guided by provider-based principles and interests. It is known as the FFS/TPP era, and it would be the dominant health care model until the mid-1980s. At that time another stakeholder group, the purchaser, initiated changes that resulted in the currently unfolding cost-containment era.

The Self-Regulatory Era

The self-regulatory era in health care began in the late 1800s and lasted until the late 1930s. During this early period health care in the marketplace evolved naturally in response to existing conditions and without much governmental involvement or interference from professional associations of providers. In the beginning health care stakeholders consisted primarily of consumers and providers (physicians and hospitals). Consumers were the purchasers of health care services. They paid for care directly, usually by a per-visit charge. The physicians and hospitals were the sellers of health care. In addition to the predominant self-pay system, however, a new form of arranging and paying for health care services emerged during this period.

By the late 1800s the leading manufacturing, mining, and transportation industries in the United States began to arrange and subsidize health care services for their employees’ job-related illnesses and injuries, particularly in rural areas where health care was virtually nonexistent. The industries found that they required a mechanism to ensure that care would be available when needed and that there would be a way to compensate the provider. They began to hire physicians as employees or, as became more common, went directly to health care entities, usually hospitals, to develop contractual arrangements for the care of workers. These industries became a third stakeholder: the purchaser. The typical service delivery arrangement was a contract for care with a specific hospital and its associated physicians. The mechanism created to pay for that care was a prepayment system in which the employer agreed to pay a fixed amount to cover the anticipated health care needs of its employees. Health care costs would be covered by the contractual arrangement only if the employee received care from the contracted hospital or physician. Because these prepayment plans typically were linked to a single hospital and its core of affiliated physicians in a community, not all physicians or hospitals in a given community participated.

Over time, and with the increasing economic uncertainty of the 1920s and 1930s, prepayment health plans proliferated. They diversified their plan structures; expanded benefits to include general medical care; and included arrangements with trade unions, fraternal organizations, employee associations, and other entities. As the Great Depression approached, consumers became anxious about access to health care. Hospitals began searching for financial vehicles to ensure a steady income stream. A robust market for prepaid health plans emerged, creating a price competitive, self-regulatory market environment. Physicians and hospitals, however, began to resist this free-market system on the grounds that it divided physicians into economic entities competing for business on the basis of price. It also limited the ability of consumers to choose freely among all legally qualified physicians and did not include all hospitals and physicians in a given community. Physicians, through county and state medical societies and the American Medical Association (AMA), began to oppose the prepayment health plan arrangements and the resulting selective contracting and price competition. Their efforts were successful.The provider stakeholder community would eventually dismantle the self-regulatory era of health care.

During this first era, however, several key elements of the nation’s health care finance and delivery system emerged. First, employer participation in the payment of employee health care was initiated. Although the actual percentage of people receiving employer-financed health care remained small, the precedent of employer involvement would prove to be increasingly important throughout all three eras of health care. Second, group health plans were financed on a preservice payment system. This innovation introduced financial risk to the hospital-physician provider system. If the prepaid premium negotiated was insufficient to cover costs of care, the provider system still was obligated to provide the care. Third, the notion of selective contracting with hospitals and physicians was introduced. Without selective contracting it would not be possible for hospital-physician systems to divide into competing economic units vying for enrollees. Of course, without competing health care systems, price competition, the fourth key element from this period, would have been severely curtailed. In short, a classic free-enterprise marketplace was unfolding in health care. It is significant that no stakeholder constituency was in a dominant market position relative to the other stakeholders. Providers, consumers, purchasers, and the health plans that increasingly emerged toward the end of the self-regulatory era, were aligning and realigning themselves as marketplace conditions changed.

This period was notable for other reasons. Notably, it would demonstrate that a stakeholder constituency could, through concerted effort and under favorable conditions, dismantle a particular market system. This fact would not be lost on those promoting price competition and cost-containment in the current period. It also established a precedent for today’s price competition. And it established that provider organizations and hospitals were capable of contracting directly with employers and other organizations without using a third-party, managedcare organization or an insurance intermediary. However, a crucial concept was lost when the free-market system was destroyed: the ability to understand the relationship between price competition and quality of care. For all practical purposes, price competition was eliminated before its full and true effects could be discerned.

The success of the provider community of physicians and hospitals working through their professional associations to defeat and eventually eliminate the self-regulatory era of price competition would be the first of two stakeholder revolts against a prevailing health care finance and delivery system. Each revolt would lead to fundamental changes in health care finance, delivery, and management, and would decidedly slant the marketplace in favor of the desires of the dominant stakeholders.

Fee-for-Service/Third-Party Payer Era

The beginning of the FFS/TPPera of health care in the United States can be traced to the mid-1930s. At that point in time, provider advocacy organizations representing physicians and hospitals began to alter the existing free-market economic system for health care in a way that would be favorable to their membership. Weller (1984) described this as the guild free choice era because the provider organizations operated in a manner similar to guilds.At heart, the economic environment that was to be created would be anticompetitive: Each physician and each hospital would become a self-contained market free of competitive pressures.

The manner in which the physicians and hospitals set about defeating the popular free-market health care system of the 1930s would determine to a great degree the elements of the second era. They successfully shifted the health care focus from the goal of the purchaser for a low-cost system to the needs of providers and facility operators. Because this provider revolt took place during the Great Depression, the advocacy organizations were able to operate without serious concerns about antitrust actions. Led primarily by the AMA, these organizations employed a three-part approach to assure that the interests of the medical community were met. First, they began a campaign to discredit prepayment plans. They drew the attention of both the consumer and the physician to the drawbacks of these plans: namely, restrictions on free choice of physicians, intimating that prepayment plans might fail financially and that “contract medicine” diminishes quality of care.

In the second and most effective part of the strategy, the AMA and the American Hospital Association (AHA) established policy positions that enumerated the principles and standards of their respective associations and were incorporated into the related medical ethics codes that practitioners were expected to follow. Through these actions the AMA and AHA were able to blunt and almost eliminate hospital and physician participation in prepayment plans. Two key policy statements set the rules. In 1933 theAHAissued its policy on hospital participation in The Periodic Payment Plan for the Purchase of Hospital Care (Weller, 1984). Basically, this policy stipulated that group hospitalization plans should include all hospitals in each community in which a plan operates, that subscriber benefits should apply at any hospital in which the person’s physician practices, and that all plans must be controlled and administered by nonprofit organizations largely composed of representatives of hospitals in good standing in the community. Application of these principles in the marketplace would severely curtail price competition in the hospital sector.

In 1934 the AMA House of Delegates adopted a policy stipulating 10 principles it required private health insurance plans to meet if they were to avoid resistance from the provider community (Starr, 1982). This policy in effect stated that all aspects of medical care should be controlled by the medical profession; that there should be no third-party intermediary in the medical care process; that there should be participation by any willing, legally qualified physician; that there should be no restrictions on patients’ choice of physicians; and, finally, that all aspects of medical care, regardless of setting, should remain under the control of a medical professional. Through application of these principles, “the AMA insisted that all health insurance plans accept the private physicians’ monopoly control of the medical market and complete authority over all aspects of medical institutions” (Starr, 1982, p. 300). These principles for private health plans were enforced through accreditation standards, and some were incorporated into state insurance codes and related association ethics codes. Physicians and hospitals faced severe consequences if they did not comply.

In the third prong of the approach to changing the health care system, the AMA did not oppose the development of health plans that were in keeping with its principles. Indeed, in the mid- to late-1930s, hospital systems and medical societies participated in establishing medical insurance plans that adhered to the policies and standards set forth by the AMA andAHA. Designed to compete against the existing commercial forms of health coverage, the first Blue Cross plans for hospital care reimbursement and Blue Shield health plans for physician services were established. They rapidly became the dominant forms of health insurance coverage.Fundamental to these plans was the elimination of price competition by including all hospitals of standing in a community in Blue Cross and community-wide eligibility for physician participation in Blue Shield. By achieving community-wide participation, the division of hospitals and physicians into competing economic units, in which closed panels of providers aligned with a specific hospital and competed for business with other similar systems, was effectively curtailed. Acceptance and enforcement of these principles in the marketplace and, in particular, in how health insurance was structured, brought to a close the self-regulatory era of health care. The variety of prepayment health plans and various health insurance arrangements of the self-regulatory era were replaced by two types of health insurance arrangements: indemnity and service plans. Indemnity plans reimbursed patients directly for most of the costs associated with health care. Except for those too poor to pay at the time of service, patients paid the physicians directly. Service plans, usually developed and managed under the watchful eyes of medical personnel, paid providers directly and usually for the full cost of care. Both types of plans were deemed acceptable because they respected physician sovereignty, kept intermediaries out of the care process, and minimized price competition. Having achieved a favorable structure for health insurance, professional associations more consistently embraced it as a financing mechanism for health care.

Over time, the professionally derived and promulgated principles served as a blueprint for the structure of a new health care market in which the finance and service delivery systems conformed to these principles. The emergence and refinement of this new marketplace structure coincided also with a several-decade upsurge in employer and government financing of health care. Sustaining innovations within the field of medicine during this same time were extending the range and effectiveness of medical care. Because in the new system physicians were paid a defined amount for each specific service provided and hospitals were reimbursed for their costs in providing care, it became known as the fee-forservice (FFS) system. The indemnity and service insurance entities created to pay providers and hospitals for services became known as third-party payers (TPPs), further highlighting the restriction of their role to that of financial intermediaries. The new system eventually became known as the FFS/TPP system. This system would increasingly dominate health care finance and service delivery systems in the United States, fueling a 50-year period of prosperity for providers and service facilities.

As the FFS/TPP system developed, certain of its marketplace and service delivery features became integral parts of almost every aspect of health care, from state insurance regulations to Medicare and Medicaid rules. In addition, the system set the guidelines for competition among providers and for relationships among health insurance intermediaries and physicians and patients. Aclose look at the system’s structure reveals that by nullifying price competition, it encouraged inflation of prices. This eventually would cause the FFS/TPP system to become the target of a number of disruptive innovations aimed at containing health care costs by modifying or eliminating its key principles. The FFS/TPP system also had a lasting effect on psychology. During this era psychology matured as a health service profession and entered the marketplace as a provider group eligible for third-party reimbursement. As such, it had to abide by the principles of the marketplace. Being part of the health service provider profession, psychology structured its educational and training programs as well as its service delivery system to fit harmoniously within features of the system.

As the FFS/TPP system evolved and the principles on which it was based became entrenched in the marketplace, the following key features emerged:

- The person who receives health care typically is not the true purchaser of that care. Rather, that person’s employer or a governmental body more typically purchases the care. This is the central dynamism of the FFS/TPP system. A fundamental disconnect exists between the patient and the true cost and payment for medical care. The patient is virtually cost unconscious.

- Care may be accessed without preauthorization. In the FFS/TPP indemnity insurance system, consumers have the right to access primary, specialty, and emergency care without obtaining preauthorization from health plan personnel. Medical necessity was determined largely by the provider, not by the insurer or the health plan.

- The care reimbursement system must be open to all legally qualified providers.Acentral tenet of the FFS/TPPsystem is known as community-wide eligibility of providers for reimbursement by third-party payers. FFS/TPPprinciples stipulate that health insurance plans operating in a given community should allow all legally qualified providers to participate. Health plans operated by insurers are not to contract selectively with providers by creating closed or limited panels of providers. This prohibition against horizontal market division ensures that each provider is a separate economic entity in the marketplace and significantly reduces price competition among providers.

- Care management is the exclusive right of the provider. Fundamental to the FFS/TPP system is the principle that third parties, such as health plan personnel, should not be allowed to participate in utilization management of patients. Such decisions are to be made within the context of the provider-patient relationship without the involvement of an intermediary.

- The FFS/TPP system is cost generating because of its capability to stimulate price-inelastic demand. The FFS/ TPP system promotes price-inelastic as opposed to priceelastic demand. In a typical economic market the price of a product or service is considered to be elastic if it is lowered to increase revenue. If a provider can raise revenue by increasing fees or by increasing utilization rates at the same or higher fees, demand is considered to be price inelastic (Enthoven, 1993). The FFS/TPP era created a price-inelastic health care system. Providers are reimbursed for each procedure performed and at a rate that equals the usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) rate for that procedure in that provider community. Hospitals are reimbursed for the costs associated with providing care in their settings. Rather than having to reduce fees to increase revenue, as is typical in a competitive free market, providers and hospitals are able to stimulate demand for more procedures and then also raise revenue by increasing fees or charges. By engaging in a form of shadow pricing (i.e., raising charges for procedures, which then become reflected over time by increases in the UCR and cost of care reimbursement rates), providers and hospitals are able to increase the amount of revenue received from third-party payers.

- Financial risk for health care is borne by purchasers and their contracted insurance carriers. The FFS/TPP system discourages providers and the facilities with which they are associated from joining forces to create a prepayment health plan and then marketing that plan directly to purchasers. In this way the system minimizes the amount of financial risk that providers and service facilities might incur in open market arrangements. In the FFS/TPPindemnity insurance and service models, health insurers are largely financial intermediaries who pay providers and facility operators for the procedures and services provided to patients.

- The FFS/TPPsystem delimits stakeholder roles in the marketplace. The principles on which the FFS/TPP system is constructed discourage cross-market competition. There is rigid segmentation or partitioning of the finance, service delivery, and management of health care according to stakeholder function. The system is designed to dissuade one type of stakeholder from taking on another’s role or function: for example, health plans combining an insurance function with a service delivery function or a purchaser contracting directly with a hospital and its medical staff. Keeping the health care market segmented into distinct stakeholder roles prevents the division of providers and treatment facilities into economic units that compete with each other on price.

The FFS/TPPera is historically important not only because of the key features just described but also because it demonstrated that a stakeholder constituency—the provider—could dramatically change the dynamics of the marketplace. And it could do so in a way that was favorable to its interests. During the self-regulatory era, no single stakeholder held a dominant position relative to the others. However, in the FFS/TPP era, the provider clearly dominated. All other stakeholders are confined to a specific function in the marketplace. In addition, during this period the health care system in the United States became dependent on the third-party purchaser to provide the financial resources to fund health care. The elimination of price competition, the fact that consumers were increasingly cost unconscious, and the dramatic rise during the period in medicine’s capacity to intervene effectively in illnesses combined to create an expensive, heavily utilized health care system with an enormous appetite for more funding. The stage was now set for a second revolution.

Cost-Containment Era

The third and current period of health care in the United States began in earnest in the early 1980s when the purchasers, increasingly and with steadfastness, began to resist paying more for health coverage. Purchasers forced health plans and eventually providers and facility operators to reduce costs. Much like the previous stakeholder revolt led by providers, this one was aimed at eliminating those features of the prevailing health care system that the stakeholder in revolt deemed objectionable. This time the focus was on eliminating the cost-increasing incentives of the FFS/TPP system. In some interesting respects the period represents a return to the early 1930s, when marketplace forces were shaping health care.

Whereas the change effort of the previous rebellion was guided from the start by principles articulated by professional associations and enforced through their codes of ethics, the cost-containment era began without a guiding blueprint or mechanism for enforcement of changes in the health care marketplace. Purchasers had a common goal of reducing the financial burden on employers and the government, but they lacked a unified and clear strategy for reducing health care expenditures. For this reason, the cost-containment era unfolded not as a concerted, well-orchestrated effort, but rather in reaction to a string of discrete disruptive innovations. These innovations have had the cumulative effect of changing the health care finance and service delivery systems in profound ways, moving health care in the United States toward a pricecompetitive, market-based enterprise.

Five key disruptive innovations were either introduced into the health care marketplace by government, employers, or insurance intermediaries or embraced by them as effective costsaving measures. The first two innovations, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and the Federal Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA), in effect paved the way for the emergence of the next two: managed competition and managed care. Managed competition would eventually provide a market-based framework for containing health care costs; managed care would provide procedures for managing providers and consumers. Simultaneously introduced into the marketplace would be carve-outs and the resultant carving out of behavioral health care from the rest of the health care system. The importance of these disruptive innovations cannot be underestimated, for they will continue to have a profound influence on the health care marketplace. The following describes these innovations, demonstrating how each changed an important feature of the finance or service delivery system of the previous FFS/TPP era or affected behavioral health care.

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

In 1974 ERISA became law. Prior to its passage employers had to purchase health care coverage through a state-regulated insurance carrier. After ERISA, businesses with 50 or more employees could self-insure their health benefits programs. ERISAwould prove to be a vitally important disruptive innovation for several reasons. First, if employers chose to selfinsure, they would not have to comply with state insurance regulations, including requirements to pay health insurance premium taxes and to provide state-mandated health benefits. This preemption from state regulation has meant considerable savings for employers. Second, because ERISA preempts employer-based self-insurance plans from state regulation, providers desiring to blunt or counter the effect of managed care on their practice would find the state legislative pathway to be of only marginal benefit. For example, after the introduction of managed care, providers wishing to eliminate the managed care strategy of using limited provider panels by working toward the passage of “any willing provider” statutes would discover that self-insurance plans are exempt from compliance with such laws. Thus, ERISAmakes it more difficult for the provider stakeholders to counter managed care arrangements, something they were able to do successfully in the 1930s to bring a close to the self-regulatory era. Third, ERISA gave purchasers financial incentive to control costs because any reduction in expenditures was retained by employers rather than becoming profit for an insurance carrier.

The ability to retain savings from cost-containment activities provided ERISA’s greatest impact: changing the flow of the revenue stream in health care and providing a fertile environment for the growth of managed care, itself a disruptive innovation. Under the FFS/TPP system, the original revenue flow progressed from the purchaser to the indemnity insurance carrier. Revenue then passed through the carrier to the patient, who had already paid the provider directly. Over time, the insurance industry would develop service plans that would allow for direct reimbursement of the provider. Regardless of which way the provider was reimbursed, the insurance carrier in the FFS/TPP model was essentially a financial intermediary who did not engage in cost-containment activities. Rather, the carrier simply provided reimbursement on a FFS basis, based on UCR rates.

As employers availed themselves of the option to selfinsure, they became ever more sophisticated health care purchasers, able to intensify price competition in the marketplace.As a result, two new patterns of revenue flow emerged. In the first, revenue progressed from the purchaser to a costcontainment entity, usually a managed care organization (MCO), before reaching the provider. The MCO became an intermediary working on behalf of the purchaser to contain costs by actively managing both providers and patients. MCOs limited access to the new revenue flow to those providers who accepted participation in cost-containment activities. MCOs thus became agents of change for the provider reimbursement and service delivery systems.

As MCOs evolved, they used more aggressive mechanisms to manage costs. They encouraged the formation of multispecialty provider organizations, channeling patients to those organizations via contracts. This accelerated the development of what became known as organized delivery systems (ODSs; Zelman, 1996). ODSs are groups of providers linked through various administrative and contractual arrangements to each other and to service facilities for the purpose of providing health care. As a result of their work with MCOs in cost containment activities, ODSs have the capability of managing utilization, conducting quality improvement procedures, and even accepting financial risk for providing health care.

With the maturation of the ODSs, a second new pattern of revenue flow emerged, one which eliminated the MCO intermediary altogether. The success of managed care in getting these ODSs to assume financial risk via capitated or prepayment systems provided incentives for ODSs to improve their ability to reduce unnecessary utilization, manage quality of care, and carry out other care management functions. Many ODSs in essence were becoming provider-initiated and administered care management systems capable of controlling costs. Hence, a new, viable health care avenue was available to purchasers. It created a fresh revenue stream that began with the purchasers who directly contracted with an ODS, eliminating both traditional insurance carriers and MCOs from the revenue stream. It was not long before sophisticated ODSs were competing with MCOs for health care contracts with purchasers. The increased viability of ODSs to engage in direct contracting with purchasers—combined with greater purchaser knowledge and competence in self-insuring health care benefits—added a new dimension to price competition. The resulting tension created further instability in an already unstable marketplace as MCOs sought to limit the potential threat represented by ODSs.

ERISA has proven to be a particularly powerful disruptive innovation. By giving employers the right to self-insure, it enabled them to have more options in contracting with health plans, including bypassing the health plans and contracting directly with provider organizations. In essence, it simultaneously undermined another principle of the FFS system and elevated the purchaser to a position of greater authority over health plans in the marketplace. ERISA also gave rise to an intermediary in the care-giving process, one which identified with the needs of health plans and purchasers to contain costs. This had the effect of defeating another FFS principle: the prohibition of an intermediary from involvement in the physician-patient relationship. It also elevated health plan authority above the providers in a newly emerging stakeholder hierarchy.

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act and the Prospective Payment System

The 1982 Federal Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) was targeted at controlling Medicare costs, but it had an unexpected effect on all health care costs and on behavioral health in particular. The most salient and wellknown cost-containment mechanism proposed by TEFRA was diagnostic related groups (DRGs). DRGs contain costs by establishing the reimbursement rate that providers will receive for treatment of a specific condition in advance. By setting fixed payment rates for inpatient treatment of medical conditions, DRGs create what has become known as the prospective payment system (PPS), yet another important modification of the existing FFS system. TEFRA moved reimbursement for inpatient hospital services from a fee per unit of service to a fee per episode of treatment. This was a radical change. Before DRGs, hospitals were reimbursed for all charges related to inpatient treatment. Through the use of DRGs, TEFRA set the number of allowable days for a hospital stay for a specific illness or procedure. Whether a patient stayed more or fewer days than the prescribed number, hospitals received the same reimbursement rate. Strong incentives were thus created for hospitals to control utilization as a way to maximize profits, versus increasing utilization to maximize profits, as had been the case in the FFS/TPP era.

The DRGs established because of TEFRA did not apply to behavioral health conditions, however. TEFRAcodified what many health care payers already knew: In behavioral health care, diagnosis of conditions did not lead to predictable treatment courses or reliable estimates for the time of treatment. Most providers of behavioral health care greeted the passage of TEFRA with great relief, not realizing that it would eventually lead to a separation of behavioral health care from the rest of medicine and cause it to be viewed as the chief spur to high inflation in health care costs. In the absence of any other cost-containment mechanisms for behavioral health, mental health care emerged as the only sector of the inpatient market still operating under the unmodified FFS reimbursement method.

The health care marketplace proved quick to adjust to regulatory changes. Many of the large hospital corporations, which saw their revenues drop as a result of TEFRA, found relief by shifting their focus onto psychiatric inpatient care.Venture capitalists and entrepreneurs rushed in to take advantage of the last unregulated part of the FFS system. Psychiatric inpatient facilities grew at a prolific rate, outstripping any reasonable projection for the need for inpatient care. Four large hospital corporations (Charter Hospitals, Community Psychiatric Center [CPC] Hospitals, Psychiatric Institutes of America, and the psychiatric division of HCA, Inc. [formerly Hospital Corporation of America]) saw double- and tripledigit growth in their facilities between 1980 and 1990 (Bassuk & Holland, 1987). A significant cause of the rapid rise in all health care costs during that decade was the exploitation by hospitals and providers of the rich benefits for psychiatric inpatient care unregulated by DRG prospective payment methods. The standard of care for chemical dependency rapidly became 28 days, regardless of the severity or duration of the problem. Hospital stays became lengthy for behavioral health disorders. By 2000 these same disorders would most commonly be treated on an outpatient basis. The excesses of the psychiatric hospitals came to a halt in the early 1990s due to high profile investigations of their operations and subsequent significant fines (Lodge, 1994). For purchasers, there was perhaps no better marketing campaign for the emergence of managed behavioral health care organizations (MBHOs).

As a disruptive innovation, TEFRA made two important contributions to restructuring the health care marketplace along cost-containment lines. First, by reintroducing a PPS, it overrode one of the basic principles of the FFS system. Second, it eventually resulted in a separate method for managing rising behavioral health care costs.Although no DRGs applicable to behavioral health inpatient care developed as a result of TEFRA, purchasers began seriously to seek other solutions to contain the steadily rising costs of behavioral health care. Eventually they would embrace carve-out MBHOs, the final disruptive innovation of the cost-containment era.

Managed Competition

In the early 1980s another disruptive innovation appeared. Enthoven and others began to propose ways to reintroduce price competition into the health care marketplace (e.g., Ellwood & Enthoven, 1995; Enthoven, 1993; Enthoven & Kronick, 1989a, 1989b; Enthoven & Singer, 1997, 1998). The price competition movement that these authors stimulated eventually would become known as managed competition. Managed competition proposes to change the nature of the health care marketplace in fundamental ways by introducing competitive pressures for cost containment and then managing how the marketplace responds to those pressures in order to prevent market failure. It intends to create conditions and forces that will compel health plans and their associated providers to manage carefully the care provided. The theory and strategies of managed competition guided the development of President Bill Clinton’s Health Security Act (1993).

Although Clinton’s efforts failed to result in legislation, managed competition principles were increasingly adopted by business and government.

Managed competition can be defined as the process of structuring the health care marketplace so that rational microeconomic market forces produce a more cost-conscious, publicly accountable, quality-focused health care system. In essence, managed competition is a blueprint for increasing competition in health care by structuring and managing a fluid market environment in such a way so as to contain costs while at the same time attempting to maintain quality of care and preventing market failure. Its fundamental goal is to change the health care paradigm from the traditional FFS model to a managed competition model that is capable of containing costs.

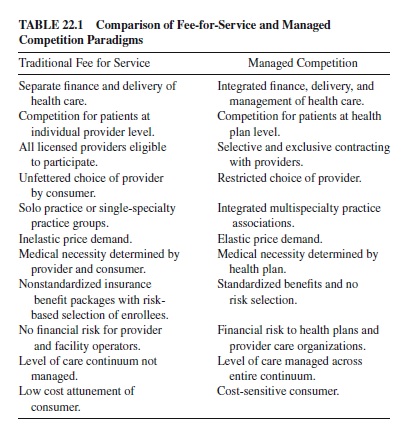

An idea of the magnitude of the change contemplated by managed competition can be gleaned from Table 22.1, which compares specific elements of the FFS health care system with the managed competition alternatives. An entire chain of change—a linked series of events among stakeholders— results from this alteration of the health care paradigm. First, managed competition advocates the need to convert purchasers into sponsors of the change process. Then they must provide those sponsors with strategies designed to change the structure of the marketplace so that health plans operate equitably and so that the more generally accepted microeconomic forces (e.g., supply and demand, price elasticity, etc.) operate to contain costs without sacrificing quality. If microeconomic forces fail to produce the desired competitive market, sponsors must adjust the strategies used to protect against market failure. Because the sponsors are really purchasers implementing managed competition strategies, they will most likely try to prevent market failure by having an effect on the stakeholders they influence the most: the health plans. In turn, health plans, in order to survive and gain market share, will need to influence the behavior of providers, service facilities, consumers, and the pharmaceutical industry through various managed care arrangements. Managed competition, should its full implementation be achieved, has the potential for the greatest impact of all the disruptive innovations to date. Even though its goals and strategies have been only partially realized up to this point, it still has had a profound effect.

Managed competition employs numerous strategies to accomplish its various goals. It aims to make the consumer more cost conscious and thus to change consumer behavior; it seeks to stimulate competition among health plans and to eliminate the noncompetitive features in the health care system; and it has attempted to develop a sponsor system capable of implementing key managed competition strategies. Making health plans compete for the business of purchasers on the basis of cost and quality through a competitive bidding process is a key strategy. By standardizing plan benefits and requiring the plans to provide performance data, the bidding process enables purchasers to compare price and quality. Managed competition also seeks to make the consumer more cost conscious by changing the degree to which and the manner in which premiums charged by health plans are subsidized by employers and the federal government. Managed competition would index an employer’s contributions to health plan premiums to the lowest cost plan available to the employees. Those employees opting to enroll in a higher cost health plan would have to pay the difference in premium charges between the lowest cost plan and the plan chosen. The goal, of course, is to encourage consumers to be sensitive to cost when selecting among health plans offered during enrollment, thereby forcing health plans to contain costs in order to be attractive to potential enrollees. Managed competition proponents also call for changing government-based tax subsidies to ensure that competition is supported and promoted, as well as to encourage businesses to continue to provide health care for their employees. Managed competition has also set into motion certain initiatives focused on changing consumer behavior. It applies financial incentives to persuade consumers to accept reduced autonomy to initiate care and to accept a limited choice of provider. It attempts to intensify cost consciousness when the consumer contemplates use of benefits by imposing higher copayments and coinsurance and by establishing financial penalties for not using the authorized provider system.

To stimulate competition among health plans, managed competition encourages the establishment of certain rules of equity. These are designed to structure the business environment in which health plans operate for the purpose of eliminating the noncompetitive features of the traditional FFS health insurance system. To accomplish this goal, health plans are required to bid on standardized benefit packages so that purchasers can more easily compare premium rates. When benefits are standardized, it is more difficult for health plans to avoid enrolling potential high-cost subscribers by not offering benefits that would adequately cover their care. Under managed competition rules, payments to health plans would be risk adjusted to ensure that the plans are adequately compensated for costs associated with treatment of high-need patients. Further, health plans are prevented from denying enrollment or limiting coverage for preexisting medical conditions. Once a person is enrolled, the health plan is guaranteed to be renewable, regardless of medical conditions, thus making coverage continuous. Health plans must accept all eligible participants who choose them. Finally, the premium level is set on a community-rating basis; that is, the premium charge is the same regardless of the health status of people eligible to enroll. Managed competition also seeks to promote direct competition among health plans in order to control costs without adversely affecting quality. To do so, it encourages the division of providers into competing economic units at the health plan level. It then encourages health plans to contract with distinct panels of providers in order to reduce the anticompetitive effects of competing health care systems that have virtually identical or highly overlapping providers. An additional approach to deepening competition at the health plan and multispecialty level is to require these entities to provide performance data on patient satisfaction, access, and quality of care. By implementing these strategies, managed competition advocates hope to make the provision of health care more price elastic, as compared with the inelastic price of the FFS system.

A final key strategy is to transform purchasers into sponsors of managed competition and then to develop a sponsor system. Sponsors contract with health plans for large groups of beneficiaries and manage the health care market environment in a way that maintains price competition.Awell-orchestrated, viable system of sponsors is central to the success of managed competition. Sponsors have several important roles. They must contain cost and maintain quality; take corrective action to protect against tendencies toward market failure in a fluid, evolving market; and guide the system in the direction of greater efficiency. In order for sponsors to gain the leverage necessary to structure and adjust the market, they must represent and purchase care for a substantial portion of the market. Three types of sponsors, all major purchasers of health plans on behalf of employees or beneficiaries, are envisioned in a managed competition market: (a) large employers like IBM or the California Public Employees Retirement System (CALPERS), which purchase health care services on behalf of hundreds of thousands of beneficiaries; (b) purchasing cooperatives composed of a coalition of employers and selfemployed individuals; and (c) government-based sponsors that purchase care on behalf of millions of Medicare- and Medicaid-eligible beneficiaries.

The various strategies collectively known as managed competition are meant to be implemented as an interlocking package in an integrated and balanced way. If this does not occur, it is unlikely that the twin goals of producing a costconscious, price-competitive health care environment and maintaining or improving the quality of care from that offered under the traditional FFS system could be achieved. There are obvious critical challenges to the full implementation of the managed competition model. First, it must have the ability to decrease the fragmentation present in the purchaser segment of the marketplace and to create a sponsor system capable of managing change of the magnitude demanded. Second, health plans in managed care systems must have the ability to develop sustainable partnerships with provider organizations. These provider organizations must be able to engender loyalty and develop allegiance among consumers while simultaneously managing the care that they provide.

Managed competition strategies and challenges apply equally to the medical, surgical, and behavioral health components of the health care system. Their state of implementation and impact to date are described later. Managed competitionis the third purchaser-linked disruptive innovation. Much like ERISA, it strengthened the authority of purchasers relative to the health plans with which they contract. It increased the number and effectiveness of strategies that purchasers had at their disposal to pressure health plans to contain costs, and it shifted a greater burden of the cost-containment mission to health plans. The stage is now set for health plans to introduce two disruptive innovations of their own: managed care and carve-outs.

Managed Care

Unlike managed competition, which is aimed at restructuring the economic principles of health care, managed care attempts to influence the health care behavior of providers and consumers. In the world of health care finance, health plans and purchasers view providers and consumers as cost centers. MCOs were formed to enable health plans to satisfy the demands from purchasers that they contain or reduce expenditures. Following passage of ERISA, purchasers understood that if they self-insured their company’s health benefits and contracted with a health plan to manage costs, they could reduce premium increases for employees’ health care benefits. Managed care consists of an evolving set of interventions focused on containing or reducing health care expenditures while attempting to maintain or enhance the quality of care provided. Although the cost reduction benefits accrue to the health care purchaser, it falls to the health plans to implement managed care strategies. In fact, as the health plan market has consolidated, the term managed has become virtually synonymous with health plans. Only a small and decreasing fraction of health plans do not manage the care that patients receive.

The beginning of attempts by purchasers to contain health care costs can be traced back to passage of the 1973 Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) act. That act provided startup grants and loans for HMOs and required employers to offer an HMO as an option when a qualified one became available. Until recently, the standard HMO service delivery system was a multidisciplinary staff model clinic that integrated finance, management, and service delivery systems. The proponents of HMOs hoped that these new ODSs would stimulate price competition in the marketplace and eventually replace FFS systems or at least force them to be more cost conscious. The competitive advantage that HMOs were supposed to have was based on their incentives to contain costs. Despite financial support for their development, HMOs emerged much more slowly than anticipated. They also engaged in shadow pricing, setting their premium rates just below that of traditional FFS plans. The anticipated competition and reduction in costs never materialized, despite the fact that HMOs managed utilization more carefully than did the FFS systems.

Within the managed care movement, preferred provider organizations (PPOs) appeared as the next cost-containment approach. PPOs divide providers into two groups: those in their network who are eligible for higher levels of reimbursement and those out of network who are reimbursed at lower rates. The patient is responsible for paying the difference between the reimbursement levels provided by the health plan and the fee charged by the provider. PPOs developed networks of providers who were willing to accept discounted FFS rates and abide by the PPOs’utilization review guidelines in return for preferred access to their enrollees. This form of managed care immediately began to express its disruptive effects on the prevailing health care system. Reluctant as it was, provider acceptance for participating in PPOs resulted in further erosion of the FFS principles as a bedrock structure for health care. PPOs began to use selective contracting with providers, dealing a serious blow to the community-wide provider concept of the FFS system. PPOs had a second major impact:The right to set prices no longer rested with the provider. Now it was the PPO that set a reimbursement rate for services. However, PPOs did continue to use the concept of reimbursing providers on an FFS basis.

As networks became more sophisticated in terms of utilization management, the next generation of managed care systems would attack another key element of the FFS system. These newer forms of managed care would begin to erode provider authority by becoming involved in more aggressive utilization management. Case managers would become active in helping to determine level, duration, and intensity of care that providers offered. The rise of an intermediary’s involvement in the care process would become one of the most problematic aspects of managed care for providers. Along with the rise of case managers came a new method of payment that directly attacked the heart of the FFS system. Managed care began to operate under a prepayment arrangement. This form of health care finance became known as capitation, and it greatly increased pressure on provider systems and health plans to contain costs. Capitation created incentives for both health plans and provider organizations to reduce expenditures in order to increase profitability. Capitation arrangements led to yet more aggressive utilization management, fears about denial of care, and concerns that quality of care would be sacrificed to maximize profits.

As MCOs gained experience in controlling health care expenditures, purchasers increasingly sought to contract with health plans that had strong managed care systems. Despite the switch from unmanaged indemnity plans to managed care plans, above-average inflation returned to health care by 1999 and 2000. This fact calls into question the actual effectiveness of the current managed care strategies in containing health care expenditures. Perhaps the enduring contribution of this phase of the managed care movement will be its disruption and nullification of key FFS principles in the marketplace. Specifically, it reintroduced the concept of financial risk to provider organizations, brought an intermediary deeper into the caregiving process, intensified selective contracting with providers and their facilities, and divided providers into competing economic entities.

Carve-Outs and Behavioral Health Care

Carve-outs represent the most important disruptive innovation developed to contain costs. They were introduced into the marketplace almost simultaneously with the larger managed care movement. Carve-outs segment one health care benefit from the rest, providing specialized administration and costcontainment controls to that segment. Pharmaceutical benefits, laboratory services, occupational medicine, and others were subject to carve-outs. But behavioral health care would experience the greatest disruption from this innovation.

Carve-outs were increasingly applied when costs rose significantly in a segment of the market, when it was hard to determine medical necessity because of the level of provider discretion in determining the amounts or types of care given, or when the dynamics in that segment of the market were different from those that mainstream MCOs could handle effectively. Health plans and the purchasers with which they interacted came to view behavioral health care as meeting all three of these criteria. There is an inherent problem with carveouts, however: They create an artificial division in the health care continuum, in effect separating a part from the main body. Carve-out companies emerged that were separately financed, and they developed independent service delivery systems. These service delivery systems were often inconvenient. For example, when laboratory services are carved out, there can be a lack of integration of that function within the medical practitioner’s office. The patient must go to a separate facility for laboratory work, frequently having to fill out additional paper work and then wait for service. There sometimes can be difficulty in reintegrating the information into the physician’s setting in a timely fashion.

Behavioral health care carve-outs posed a more serious problem. Because functions overlap between primary care and behavioral health care, consumers may not know where to access care for behavioral health concerns. In fact, a significant portion of the care is still provided by primary care physicians. Even more serious, behavioral health carve-outs make it more difficult to coordinate care for a broad range of medical conditions that have high comorbidity rates for behavioral health problems. In addition, they impede the ability of the rest of the health care system to utilize fully the skills of the behavioral health specialist. Such specialists have the capability to help patients change health practices or make lifestyle adjustments that would prevent chronic health conditions from developing or prevent exacerbating already existing conditions. Behavioral health carve-outs have come to have broader implications than being simply a different company managing mental health benefits; they have also come to represent a separation of the skills of the behavioral health specialist from the broader needs of medical and surgical care patients.

Behavioral health care was among the first areas singled out by health plans for management via carve-outs.The use of carve-outs as cost-containment strategies in behavioral health care gave rise to a new form of MCO, the MBHO. Two distinct types of MBHOs quickly emerged: the multidisciplinary staff model clinic (the clinic model) and the external intermediary utilization review organization (the network model). The clinic-model MBHOs were staffed by salaried providers and were often funded by capitation, a new form of financial risk taking that was similar to the older prepayment system of the self-regulatory era. Capitation funding arrangements pay a fixed dollar amount per enrollee per month to a clinic; the clinic in turn is expected to provide all medically necessary behavioral health care. Capitation funding is viewed by purchasers as a method to predetermine their costs for behavioral health care and as a way to create incentives for providers and their clinics to contain costs.

The early clinic-model carve-out MBHOs frequently had contracts with one or more local employers to provide behavioral health care services. Direct contracting with purchasers gave these companies a connection to employers similar to the ones that had developed during the self-regulatory era. Seeing a business opportunity, entrepreneurs quickly began to develop clinic-model carve-out companies in behavioral health care. Soon a variety of clinic-model MHBOs became active in the marketplace. Despite their variety, they continued to manage utilization and coordinate care internally. No external intermediary was involved in utilization management.

The network model represents the second type of MBHO to develop. It grew out of utilization review organizations that had been active for several years in general medical and rehabilitation care sectors of the health care market. These organizations saw the opportunity to expand into behavioral health care. They extended and modified their care management and utilization control procedures and then began marketing themselves to purchasers as MBHOs. Early on the utilization review organizations did not have contractual relationships with providers; their only contact was with purchasers to contain costs. However, they quickly realized that it was difficult to manage providers with whom they did not have a contractual arrangement. This gave rise to the network model of behavioral health care, which enabled utilization review organizations to develop contractual relationships with providers. Unlike in the clinic model, these companies did not directly employ behavioral health care providers. They contracted with providers on a discounted, FFS basis. One key element of the contract was the provider’s agreement to abide by the company’s utilization management standards. Utilization review organizations thus were transformed from those that could only attempt to influence providers to curtail services to ones with power to dismiss from the networks those providers who did not abide by their utilization management principles.

The network-model MBHOs developed a number of utilization management strategies to contain costs. First, they began requiring precertification for inpatient facility treatment. Next, they developed guidelines that specified intensity and duration of treatment for major disorders. At the same time, they began contracting with psychiatric inpatient facilities to align their own financial incentives more closely with those of the hospital. They also promoted development of a broader continuum of care, encouraging partial hospitalization programs, intensive outpatient care systems, and other forms of care that could contribute to cost containment. This necessitated coordination of care across the range of interventions and accelerated the rise of the case manager who is external to the provider-patient relationship.

The network utilization management model established several key precedents in behavioral health care. First, it initiated selective contracting with behavioral health care providers. Second, it introduced discounted FFS rates and prevented the practice of billing patients for the difference between the full fee of the provider and discounted rates. Third, it reduced provider authority by imposing an intermediary in the provider-patient relationship. Eventually, these intermediaries began to rely on treatment protocols to manage utilization; many of these protocols were not based on empirically validated principles. Fourth, they contributed to the migration of the psychotherapy function from a primarily doctoral-based activity to the subdoctoral level. The network model, along with the clinic model, also set important precedents by taking on financial risk through capitation and other funding methods. The use of risk-based funding mechanisms led to concerns among providers and patients about denial of care and quality issues. In response, MCOs established quality improvement programs and participated in health care accreditation processes.

Each of the two MBHO models would in turn develop a variety of service delivery and finance systems, which actively competed among themselves for marketplace dominance. In the 1990s eight network, clinic, or combination care management models were in use in the marketplace (Drum, 1995). By the turn of the century, the network model dominated. The clinic model proved to be expensive and complicated to create. To enable a group of providers to work together required setting up facilities, administrative support structures, and quality and utilization management systems. In addition, the clinic model proved difficult to expand beyond local markets and could not compete for contracts with large purchasers who needed regional and national provider systems. Network models, on the other hand, could quickly establish networks in virtually all areas of the country. In a classic market oversupply situation, network-style MBHOs were able to find an ample supply of providers willing to contract with them at steeply discounted rates. MBHOs could expand and contract networks as market forces required, and they could do so inexpensively. They could reconfigure their products according to the needs of purchasers. In a given region where multiple MBHOs operate, provider networks often use the same providers. Consequently, differences in quality are not significant among the various MBHO networks. Price reduction thus becomes the only competitive advantage that MBHOs have as they seek contracts from purchasers.

The inability to apply DRGs to behavioral health care, the receptivity of self-insured purchasers to contract with MBHOs on a carve-out basis, and the use of managed competition principles to promote competition among providers and stimulate cost consciousness of consumers all provided a robust environment for MBHOs. Their success in containing and reducing costs for self-insured health plans stimulated insurance companies to begin using their services. The growing market for MBHOs attracted venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, signaling that the race for market share was underway. Competition for market share played into the hands of purchasers who continue to seek price reductions.

Most insurance companies did not have the expertise to construct an MBHO internally. They either contracted with carveout MBHOs or purchased them. MBHOs that contracted with or were acquired by insurance companies gained immediate access to a large number of insured lives, expanded their national presence, and, of course, gained marketshare. The MBHOs that did not develop contractual relationships with insurance companies often merged and consolidated with other smaller MBHOs and employee assistance program (EAP) companies. This consolidation began in the late 1980s and occurred throughout the 1990s. The drive for growth frequently overlooked the differences in culture and style between many of these companies, as well as the unique and often-incompatible information and technology systems they had developed. By early 2001, the largest MBHOs reported covering over 100 million lives (according to the following behavioral health care company Web sites consulted on May 29, 2001: United Behavioral Health at http://www.unitedbehavioralhealth.com/ubh/ubhmain/aboutus.html, Magellan Behavioral Health at http://www.magellanhealth.com/mbh/about_us/fast_facts.html, ValueOptions at http://www.valueoptions.com/news.htm, and CIGNA Behavioral Health at http://www.cignabehavioral.com/ about_corp.htm). Clinic-model MBHOs in the year 2000 did not fare as well as did network models. Of the small percentage of clinic models that managed to make the transition from local to regional clinic systems, few of those survived the shift from contracting on a regional basis to a national level in this highly fluid environment.

By the beginning of 2001, the consolidation of MBHOs had resulted in two types of network-based MBHOs: independents and affiliated or owned. Each has fundamental weaknesses as well as strengths. The independent model enjoys tremendous flexibility in selling its products to any health care organization in the marketplace. But it lacks a stable base of contracts from which to build its operations, and it may not have access to the type of technology required to execute core functions—a technology that large insurance companies have in ample supply. Managing a large number of contracts with various requirements across different information systems in use as a result of mergers is difficult and expensive. Owned affiliated MBHO companies, on the other hand, do not have the same difficulties. They often have access to systems and technology that otherwise would not be affordable for an independent model. They also may have exclusive contracts to manage the behavioral health care benefits on a national basis for their owners or affiliates, thus attaining a stable source of revenue.

The managed behavioral health care industry has seen rapid development and change in the last1 8 years.Anindustry that started as a collection of small entrepreneurial companies has grown into a highly consolidated one. The diversity of models that were implemented when the industry began has evolved into a network model dominated by large MBHOs that manage millions of lives. Large MBHOs are plagued, however, by the same problems that derailed large national health care organizations: the lack of adequate technology and systems to manage rapid growth. The competition for market share has driven prices so low that companies are now struggling to make sufficient profits to invest adequately in their infrastructures.

MBHOs had a substantial impact on providers, in particular the psychiatric hospitals. By the end of 2000 all the major psychiatric hospital chains were out of business, either sold or bankrupt, leaving many parts of the country without a psychiatric hospital. Individual practitioners have lost some autonomy. They are often asked to follow treatment guidelines that are not empirically validated. Also during this period there has been a dramatic increase in the number of behavioral health professionals eligible to be licensed to provide care. States passed legislation allowing professional counselors to practice independently at the master’s-degree level. The result has been a downward migration of the psychotherapy function. Once practiced primarily by psychiatrists and doctoral-level psychologists, psychotherapy is now increasingly practiced by providers with 1 to 2 years of graduate education.

The behavioral health care carve-out has proved to be a vitally important disruptive innovation for several reasons. First, it contributed to a mind-body split in health care that reduced reliance on the use of more biopsychosocial approaches to the treatment of health conditions. Second, it brought a unique form of managed care to behavioral health care—one with its own industry dynamics and costcontainment procedures. Last, carve-outs further emphasized that psychotherapy was not a physician activity. As a result, the scope-of-practice laws, which constrain medical functions from migrating to other types of providers, do not apply to psychotherapy.