Sample Group Psychotherapy Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Human beings thrive in a community that values their participation and protects their dignity. We all need support, wisdom, and compassion throughout the life cycle, and we look to our natural groups for that kind of sustenance. When individual capacity fails and when suffering becomes too draining on one’s resources, the therapy group can offer just such a community of peers to help heal human misery and to nurture continuing healthy development.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

This research paper develops the concepts of group psychotherapy in the twenty-first century. For a host of reasons—the search for community because we have moved away from our natural villages, the added value that psychological theory places on the relational field, and the sheer economy of the treatment model, given the financial constraints of the mental health field—group psychotherapy stands as a very viable and rich option for mental health care.

The initial section reviews some of the historical underpinnings and the basic concepts that hold across a range of theories. We summarize the main theories, paying attention to places where the theories inform the various goals and techniques. The larger part of this section is devoted to psychoanalytic group therapy and technique.

The second major section focuses on briefer group treatments and on inpatient and partial hospitalization groups. This section addresses aspects of symptom-specific and population-specific group therapy.

A third section reviews the current research about group psychotherapy.

Historyand Evolution of Group Psychotherapy

Early Beginnings

Group psychotherapy originated in America in 1905 and was first conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital by an internist, Joseph H. Pratt (1922), who led groups composed of patients with tuberculosis. He referred to these groups as classes, and they bore remarkable similarity to those currently offered by cognitive-behavioral groups, psychoeducational groups, and self-help groups to alleviate the distress caused by commonly shared physical or psychological problems. A few years later, Trigant Burrow (1927) coined the term group analysis and conducted group therapy for noninstitutionalized patients. In the early 1930s Louis Wender (1940) introduced the notion of the group as a recreated family, applied psychoanalytic concepts to group therapy, and began the use of combined therapy.

Samuel Slavson (1951), an engineer by profession, founded the American Group Psychotherapy Association in 1948 and is regarded as having had the most influence on the development of American group psychotherapy. He referred to his method as analytic group psychotherapy and concentrated on the individual in the group rather than on the group itself. His greatest contribution is acknowledged to be the development of group psychotherapy with children. During the 1930s and 1940s Wolf and Schwartz (1962) actively applied the principles of psychoanalysis to groups of adults.

Group psychotherapy also created interest in Europe. A Romanian psychiatrist, Jacob L. Moreno (1898–1974), primarily identified with psychodrama, borrowed from his experience with the Stegreiftheater (Theater of Spontaneity in Vienna). Thus, his introduction of group psychotherapy in 1910 included role-playing and role-training methods (Moreno, 1947). Moreno may have coined the term group therapy in 1931. Although he never formally conducted group psychotherapy, Sigmund Freud called attention to group psychology in Group Psychology and Analysis of the Ego (1921/1962). Freud’s insights into group formation and transference reactions form the underpinnings of modern psychoanalytically oriented group psychotherapy, from both the group to the individual and the individual to the group. Kurt Lewin (1947) introduced field theory concepts, emphasizing that the group is different from the simple sum of its parts. Lewin coined the term group dynamics in 1939 and is considered the pioneer of viewing the group as a whole.

In England, group therapy evolved largely as a result of the pressure to treat a large number of psychiatric casualties during World War II. Wilfred R. Bion (1959), an analysand of Melanie Klein’s (1932), offered the hypothesis that the group has a separate mental life, with its own dynamics and complex emotional states, which he terms basic assumption cultures. His basic assumptions paralleled Klein’s stages of infant development. Bion is best known for his work with the group as a whole, and his ideas have gained immense popularity in the United States. Henry Ezriel (1950) and John D. Sutherland (1952) were also active in group therapy, emphasizing the here-and-now and then-and-there perspectives. Ezriel is credited as the first person to describe the transferences between the members themselves and between the members and the group as a whole.

The distinction has been made between therapy in a group and therapy through a group. In the former case, the group leader administers the same therapy—either simultaneously or seriatim—to the entire group as that performed with individual patients. In therapy through the group, members play a critical role in the therapy—particularly through modeling and reinforcement procedures and other elements of group dynamics.

However, early in the study of groups, a fear of possible negative factors surfaced, voiced not only by Freud but also earlier by LeBon (1920) and others. When conditions are favorable, groups enjoy the power that comes from contagion. Contagion is a process by which members of a group are pulled into an activity in which they might not engage by themselves. At its most pernicious, it is the process that turns a group into a mob (LeBon, 1920). At its more benign, it is a centripetal force that entices a person—as a member of a cohesive group—to protect the cohesiveness by joining in the shared activity or pool of affects. When this activity takes the form of risking exposure to shame by disclosing and remembering hitherto-repressed material, the analytic process is moved along toward further resolution.

History of Inpatient Groups

Since the time of Hippocrates (around 300 BC), mental illness has been viewed as a condition with similarities to medical illnesses, and hospitalization or institutionalization has been employed in an effort to heal the sick. The first psychiatric hospitals were established in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century and soon were followed by a handful of institutions in the United States that were devoted to the treatment and care of the mentally ill.

Inpatient group therapy in the United States can be traced to two roots: the therapeutic community or milieu therapy movement and the group therapy experiments of the early twentieth century. Among the first milieu therapies was that offered at the Menninger Foundation in Kansas in the 1930s. There, hospital treatment was based on the premise that different types of social interactions could be used to benefit individuals suffering from various mental disorders (Menninger, 1936). The earliest psychiatric groups offered in hospitals in this country were at Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts (Sadock & Kaplan, 1983). There, a former minister-turned-physician named L. Cody Marsh began giving lectures about mental illness to patients over the loudspeaker and organizing discussion groups. Patients were required to pass an examination before they could be released. About the same time, Lazell (1921) was holding classes for patients with schizophrenia at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC, teaching them about the psychoanalytic roots of their problems. During World War II, groups were used in several military hospitals—in part as a way to treat many patients simultaneously with fewer demands on the staff. At the Northfield Military Hospital in England, Bion, Foulkes, Ezriel, and Main (1965) introduced the idea that the psychiatric unit in its entirety is a group, and as such, it had therapeutic benefit in all of its parts.

Foulkes’ approach was to bring a psychoanalytic awareness to all types of group activities that occur in the hospital and to maintain sensitivity to the interaction between the group and the hospital unit (Rice & Rutan, 1987). He believed that the community in which the patient lived is a group with its own healing powers, thus emphasizing the importance of the milieu in the treatment of hospitalized patients. In particular, he was aware of how the hospital itself was a large group, of which the therapy group was a smaller part. Each part was affected by events in or around any other part. Theories of group therapy have evolved from these early experiments, and most hospitals have included group therapy since that time.

The concept of the milieu as therapeutic is generally attributed to the work of Maxwell Jones (1953) in England. Milieu therapy revolves around the belief that the social environment of the patient supports and enhances his or her recovery. All the relationships within the hospital unit are considered part of the milieu: patient to patient, patient to staff, staff to patient, and staff to staff. During the milieu therapy movement, patients and staff were jointly responsible for many decisions, such as medication changes, privileges on the unit, activities, and so on. Any interactions involving patients were seen as opportunities to learn about the patient’s problems and make efforts toward change (Rice & Rutan, 1987). This concept—in one form or other—has been seen as a central organizing tenet in most inpatient settings since the middle of the twentieth century. It has suffered with the sweeping changes imposed on hospitals in the past decade or so of managed care limitations, but it remains an essential tool in the treatment of psychiatrically hospitalized patients.

Mainstream Group Theories and Therapies in the United States

The field of group therapy has incorporated the historic influences into a solid clinical modality as articulated by the stellar work of a number of theorists in the United States and by their followers. Helen Durkin (1964) integrated principles of systems theory with group dynamics into the field of group therapy. Along with Durkin, Henrietta Glatzer (1962) became a prime force in the application of psychodynamic principles to group psychotherapy. She is known primarily for the concept of the working alliance. “She used the concept to emphasize the importance of the member-to-member interaction as a principal component of the working alliance in therapy groups” (MacKenzie, 1992, p. 305). Saul Scheidlinger’s prolific output has set the stage for a broad-based view of group development; this view includes concepts such as the mothergroup and the regressive pull in groups that activates early childhood patterns (1974).

Principles of Group Psychotherapy: Basic Theories

Although group therapy was originally based on psychoanalytic principles, now a broad range of theories informs its practice.

Psychodynamic Theorists

Most current analytic theorists define the psychodynamic umbrella as consisting of four major branches: classical theory, object relations theory, ego psychology, and self psychology. In addition, the scope of the analytic umbrella covers interpersonal theory, humanistic-existential theories, and feminist-analytic thought.

Classical Analytic

The classical analytic emphasis on libido and aggression finds expression in the unconscious forces that propel the group as a whole along its epigenetic trajectory. In this model the group develops along the same epigenetic trajectory as the individual—namely, oral, anal, phallic, and genital imperatives dictating the movement from early to mature group stages.

Object Relations

Object relations theory finds in groups a natural environment for the projections of internal part-objects onto the other people in the room (members and leader) and the gradual reintrojections of the split-off aspects of the self within the containment of the group envelope. This term defines a sense of impermeable cohesion among the group members. Internalized partsobject is a term to describe critical emotionally laden aspects of significant people, which the child incorporates into the self. These aspects then shape the person’s views and expectations of important people in subsequent interpersonal contacts.

Ego Psychology

Anna Freud’s (1966) interest in ego defenses, by which an individual copes with potentially devastating anxiety, influences a host of group interventions having to do with recovery from physical or mental illness. Health psychology is a current branch of what the ego psychologists were addressing.

Self Psychology

Self psychologists recognize the mirroring and empathic possibilities among committed members who can serve as selfobject functions for one another. The term selfobject implies that other people are present only to gratify the needs of the nascent self and not as autonomous entities. As the members gratify this universal early need for one another, each can stabilize a sense of greater and more flexible self-esteem.

Intersubjective Theorists and Relational Theorists

The obvious value of the group to people committed to the concept of a cocreated reality makes the group therapy a treatment of choice. There is no hidden place in the group transferences either among the members or with the leader. All are influenced and in turn influence one another in developing new sublimatory channels and emotional options. This synergy is consistent with the principles that undergird intersubjective theory.

Related Analytic Theorists

Sullivanians and other interpersonalists such as Yalom and Lieberman (1971) stress the healing that comes from the real relationships among the members, and the feminists see in groups the opportunity to inspect the impact of gender on environment and vice versa. Existentialists depend on the group to explore, verify, and accept the individual’s personal myth and intentionality in the world as they contribute to the individual’s self-authenticity.

Gestalt Theorists

Many of the theories that developed in the 1960s and 1970s utilized group models. The theory of Gestalt therapy is defined by two central ideas: First, the proper focus of psychology is the experiential present moment; second, it is only possible to know the self in relation to other things in the interactive field. Gestalt theory as developed by Perls, Goodman, and others from the Cleveland Gestalt Institute brought the field theory of Lewin and Goldstein (1947) to bear on patients’ attempts to integrate action, affect, and cognition. While working with an individual protagonist within the group, these thinkers utilized the whole group as a supportive container and reactor to the protagonist’s clinical development. In Gestalt theory, the focus is on organizing the accumulation of past experience into the present reality of the person. Thus, the balance between figure and ground (or content and process) is the direction toward health.

Transactional Analysis

Transactional analysis divides personality into three phenomenological components or ego states, colloquially termed Parent, Adult, and Child. Berne (1959) developed a group therapy approach that understands social behavior in terms of strokes or transactions exchanged by people in maladaptive patterns called games.

The Redecision School of Transactional Analysis focuses on ego state patterns, which may be thought of as character patterns, as expressed in the individual’s relationship with others; these clinicians seek to resolve maladaptive early life decisions through contracts for change (Kerfoot, G., & Gladfelter, J., personal communication).

Nonanalytic Theorists

In addition to the psychodynamic theorists who have dominated the field of group therapy, a host of other theoreticians have contributed to the field of group psychotherapy. Some of them include the cognitive-behaviorists, the Gestalt theorists, transactional analysts, and the redecision therapists.

Cognitive-Behavioral Theorists

Cognitive-behaviorists see in the group model the opportunity to rethink old cognitive schemas and to question some of the prior cognitive distortions. Behavioral clinicians address social and psychological problems within a testable conceptual framework; thus, the social influence that occurs in groups has a pivotal role in altering maladaptive responses by the use of modeling and reinforcement of new behaviors.

Group cognitive-behavioral therapy can be discussed in terms of skills that are taught, problems that are addressed, or specific behavioral techniques that are used. There are several critical skills that are taught to groups of people who may or may not have psychiatric-psychological dysfunction or impairment but who are suffering from the consequences of skills deficits and may experience an increase in well-being and gratification from the acquisition of such skills. Examples of skills that may be taught in a group therapy context are job-seeking skills, negotiating skills, parenting skills, and communication skills.

In behavioral group therapy, some structures exist that are similar to those in other orientations—the size of groups, matching with respect to the nature and severity of the problems (heterogeneous or homogeneous), age of the patients, open-ended or time-limited, single leader or coleaders, concurrent individual treatment for group members, agreements around confidentiality, and rules of conduct within the group and outside the group. Because of the short-term, problemfocused nature of behavior therapy, most groups are conducted at weekly intervals for 8–12 sessions of 1–2 hours duration. A greater number of fixed-session groups or openended groups are used for patients with multiple or complex problems requiring more time (Fay, cited in Alonso & Swiller, 1993).

Therapeutic Factors Common to All Group Psychotherapy

Whatever the model, group therapy rests on the assumptions that healing factors emerge and operate in all groups. Some of these factors can be brought into play to allow the individuals within the group to grow and develop beyond the constrictions in life that brought that person into treatment. Although some group theorists rely on a cluster of factors relevant to their models of the mind and of pathology, all utilize some of the whole group of therapeutic factors identified previously.

The analysts generally rely on the recapitulation of the family of origin and on the way the transferences develop relative to those early family experiences. The cognitive behaviorists exploit the factors that most rely on examining and clarifying schemas or thought patterns and cognitions.

Group Goals

It is obvious that to some extent, the theory used points toward the desired goals of the group, yet some goals are universal to all group therapy. These goals include offering a supportive community to the patient, relieving symptoms, increasing self-esteem, and freeing the patients to move toward their life goals. The particular directions that the work will take are more specific to the theoretical base of the leader and the treatment, as we discuss in the following sections.

The Goals of the Open-Ended Psychodynamic Therapy Group

Character change is the main goal of the psychoanalytic group. The standard target for psychoanalytic groups in particular (as well as for many others) is the reawakening of early neurotic and characterological problems in the transference that emerges in the clinical hour. The emergence of repressed and avoided conflicts or of troubling internal partobject personification in the therapy group is facilitated by the multiplicity of transference targets and the powerful impact of the aforementioned curative factors. In this model it is assumed that people will have their problems in the context of relating to the other people in the room. As the transferences from member to member, from member to leader, and from member to the group as a whole develop, people reexperience some of their earliest conflicts. Resistance emerges and can be explored, thereby illuminating the underlying defensive structure of each individual. With increasing safety, members regress to earlier defensive modes and arrive at increasing insight into the underlying personality dilemmas. These dilemmas can then be experienced and analyzed in the group—both by the other members and by the leader. Initially this process can feel shaming and threatening in a number of dimensions. However, with each event all the members become more deeply aware of their own projections and displacements, and they can gradually reown those split-off parts of the self; when this happens, the splits, which had depleted the ego, are healed, and psychic energy is made available for the conscious goals of the ego. Transference distortions give way to clearer relatedness with others in the here and now. The individual is now available for true intimacy with a separate but related other.

Members in this kind of group are selected from along the whole spectrum of ego development. The main criterion is that individuals are able and willing to make a commitment to pursue in-depth exploration of their internal lives.

Some of the earlier literature on group treatment expressed doubts about the appropriateness of this uncovering kind of group for the sicker patients. Currently the tide has shifted; researchers (Kibel, 1991) argue that group therapy is the treatment of choice for the pre-Oedipal patient with early impairment that interferes with a mature and goal-directed life. These patients have been referred to as pre-Oedipal or characterologically impaired in either primary or secondary process organization (Axis I and Axis II). In fact, it seems that the distributed transferences in the group mitigate an overly threatening regression for such patients (Alonso & Rutan, 1983). Character difficulties are tenacious for all human beings—from the healthiest neurotic to the most regressed patient. For all people, character problems are

- Outside the patient’s awareness.

- Syntonic—that is, perceived as who I am when brought into awareness.

- Resistant to change even when the patient wants to make such a change.

- Repeated compulsively until worked through—that is, they are robbed of some of their power with each experience of successful change to better alternatives.

- Difficult to change without strong motivation to overcome psychological inertia.

The tide of group belongingness provides the necessary motivation.

The Goals of Cognitive-Behavioral Groups

The importance of practicing techniques and skills within the group cannot be overestimated. The group becomes a laboratory for trying out new behaviors in a supportive context. Reinforcement is provided by other members of the group to encourage practicing per se and also to support successive approximations to the desired level of proficiency. Finally, maladaptive schemas are adjusted so that a patient’s thinking is more closely related to the reality principle. Thus, feelings about the self and others become less troublesome.

Support Groups of Various Kinds

Symptom-Specific Groups

Since 1905 when Dr. Pratt offered his classes for patients with tuberculosis at the Massachusetts General Hospital, people have come together to commiserate with one another around the common symptom or set of symptoms, to share information, and to learn how to deal with that symptom’s impact on their lives. Groups have been organized around medical illnesses such as cancer and diabetes; around psychological problems such as eating disorders, phobias, or bereavement; and around psychosocial sequelae of trauma such as war or natural disasters.

The goal of such groups is to provide support and information embedded in a socially accepting environment with people who are in a position to really understand what the others are going through. The leader of such a group needs to be familiar with the symptoms, sophisticated in the treatment of these symptoms as well as the whole patient, and competent at providing and sustaining adjunctive care as needed. The treatment may emerge from cognitive-behavioral principles, psychodynamic principles, or psychoeducational ones. Frequently these groups tend to be time limited, and members often join at the same time and terminate together.

The emergent self-help movement has generated groups that differ from the previously mentioned ones in a number of ways. Self-help groups are egalitarian and leaderless, focused on the principles of universality and unconditional positive regard, and open-ended and variable in their membership. Their goal is not necessarily to promote interaction among members; indeed, most discourage the kind of interpersonal discourse that is commonly found in the group therapies described previously. The common enemy is the disease, and the common bond joins the members in a resistance to succumbing to the ravages of that disease.

Self-Help Groups

Alongside group therapy offered by the professional community, a large array of self-help groups have emerged and flourished. The first of these was Alcoholics Anonymous, which became a model for many other problem-specific support groups led by their own members. These groups have become a major source of recovery and cure, and they illustrate the value of community and group cohesion for managing a range of human distresses. In particular, they focus on compulsive problems, such as substance addictions of all sorts, self-mutilation, and gambling.

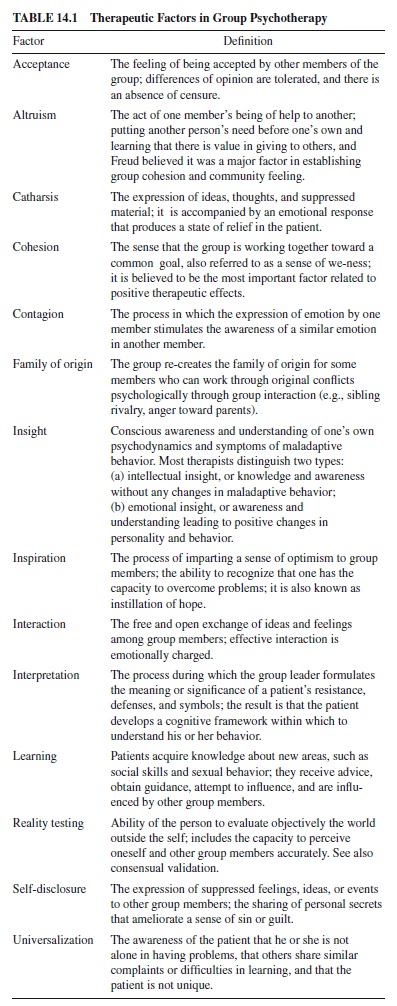

All of the modalities listed previously have in common certain curative factors. Table 14.1 is a partial listing of the range of therapeutic factors in group therapy.

The Developmental Map of a Therapy Group

Since Bion’s (1959) original work on group development, it has been customary to look at all therapy groups along a developmental trajectory. Although it is obvious that developmental theorists will emphasize a group development model consistent with their own branch of dynamic theory, there is nonetheless some agreement among all group therapists that any consistent group usually undergoes some initial stages of group formation and cohesion; it then moves to some level of differentiation among its members and then finally achieves a stage of integration of new learning and new maturity.

Techniques for Conducting Open-Ended Psychodynamic Group Therapy

This section focuses on open-ended psychoanalytic group psychotherapy as a basic model for treating patients with developmental conflicts and deficits. The first considerations for conducting a psychoanalytic group include

- Developing a contract that gives meaning and structure to the work in the group.

- Building the alliance both before and in the group. After the individual’s personal dynamics are deemed as appropriate to group treatment, then the leader will want to explain the rationale by discussing the factors described previously, to help forge an alliance with the patient around the usefulnessofsuchafocus,andtofollowupwithacarefuldescription of how the group works, a preview of what the patient can expect to see unfold in the first meeting and in subsequent meetings, and a full discussion of the group agreements to which all the members of that group are agreed.

- Interviewing the patient to screen for the appropriateness of group treatment. The ideal composition of a psychoanalytic group is one in which the members share a fairly homogeneous level of ego development and are variable in character style and personality. This mix allows for a capacity of empathy among the members and at the same time avoids too common a set of defensive operations.

- Preparing the patient for working in the group. The value of preparing a patient for what to expect in a therapy group cannot be overemphasized. It is difficult to overcome the natural resistance to speaking with strangers about one’s intimate life. Problems of early shame and exposure account for many early group dropouts and in either case are not conducive to trust building among the members. A frank discussion of the common fears, a clear description of how the group works, and some statement of the leader’s role mitigates this resistance. It is also useful to explore the patient’s wishes and fantasies about the group and to help detoxify the early intrusions of other members on the new members’ privacy and equanimity.

The Work of the Analytic Group

Sources of Conscious and Unconscious Data

The primary data in analytic treatment are basically what the patient says, what he or she does, and how he or she characteristically is. It is from these immediate behavioral data that we as therapists derive explanatory notions of unconscious material and defensive operations. Clearly, the more we have of such data, the better. The more we can see of our patient in action, the more the patient and we can understand about the patient and alter what is potentially alterable.

The group does allow for the direct observation of the patient’s actual functioning, dysfunctioning, or both. The group allows for the patient’s own reporting of internal and external experience and for his or her perceptions of and responses to the therapist. It also provides more people to whom he or she can respond and more people to react to those responses. The data are active, not passive. The arena for transference is extended from its traditional vertical axis to a horizontal one involving many different objects and—on occasion— transference is extended to the group as a whole.

Furthermore, because the stimulus conditions are not generally subject to the patient’s control, his or her responses are likewise less controlled. Although we may not get as pure a picture of the transference, we do get a much more complete picture of the patient’s character strength and pathology in action. Not only the therapist but also other patients and the patient him- or herself have the opportunity to observe these spontaneous, unedited responses and enduring behavior patterns reactive to both constant and occasional stimuli. This far more complex portrait of the patient with all his or her strengths and weaknesses—this kaleidoscopic view of the person—is a direct function of a multimodal treatment situation.

Group process is the closest analogue in the group setting to the free association process in the dyadic setting, and it is to facilitate this process that the leader is dedicated throughout group treatment. The unfolding of the group process resembles that of free association, but it exceeds intrapsychic boundaries and moves to both a horizontal plane (between members) and a vertical plane (member or members to therapist). It involves the whole array of transference and resistance, ego function and dysfunction, and symptoms and character defenses. The working assumption in this model of group therapy is that if the group process operates at full tilt (i.e., if the resistances—group or individual in origin—are consistently and successfully addressed) the many mutative forces of the group will also operate at maximum capacity to the benefit of each individual member. In this sense the group process is both a product of and an agent of the analytic process as it is carried out in the group. Thus, the group process has a curative force of its own while serving as a condition for individual growth (Kauff, cited in Alonso, 1993).

Common Phenomena in Psychodynamic Group Therapy

Analytic groups rely on unconscious defenses to emerge in the interactions among the members. Groups have been described as a hall of mirrors, with each member seeing a disowned aspect of the self in the other faces in the mirror. Put another way, the members contain the projections of one another, and at times, they become the unconscious participants in each others’projective identifications, in which one person accepts the disowned parts of another in return for similar accommodations. It may well be that the exposure to and resolution of multiple oscillating projective identifications is the primary avenue for the healing and for allowing the patient to reintegrate the split-off pieces of the self and restore a previously compromised ego.

Organizing and Conducting an Open-Ended Psychodynamic Group

The clinician needs to attend to a variety of factors in planning such a group. These factors include defining the meaning and goals of the work and describing them to potential group members. The composition in such a group ideally consists of people with fairly homogeneous levels of ego development, which maximizes the capacity of members to empathize with one another. The group members might be heterogeneous in most other respects. The leader should try to develop a clear set of shared group agreements relative to time, attendance, fees, and other external considerations, such as third-party payer intrusions into the work. As each individual is interviewed for the group, these goals and agreements should be fully discussed, including some awareness of how the group and the leader will in fact relate to one another in the room. Careful pregroup discussions can go a long way toward reducing early dropouts and the subsequent painful disorganization that can follow such disruptions.

After the group begins, the leader is in a position to observe member strengths and resistances, paving the way for healthy relatedness and analysis of neurotic patterns.

Activity, Inactivity, and Neutrality

It is important to distinguish among inactivity, neutrality, and passivity. There is no room in any legitimate therapy for the clinician to remain intellectually and emotionally passive; he or she owes the patient full attention and deliberate concentration on all aspects of the treatment, in or outside the therapy hour—in this case, the group meeting. While remaining vitally ego-active, the psychodynamic clinician should avoid action that interferes with the flow of the patients’ associations or that otherwise dictates the direction of the meeting. Similarly, the clinician in this model should strive to maintain a neutral stance toward the material, being careful to analyze and investigate all aspects of an event or a set of feelings; this does not mean that the clinician is neutral toward the patients in the sense of not caring about their well-being—or for that matter, avoiding feelings of concern, affection, irritation, or dismay about the patients in the course of a long-standing and emotionally involving treatment. Thus, what we are referring to in this paper is therapist inactivity and neutrality, which are expressed in a parsimony of words or action or direction on the part of the analytic clinician. We are therefore defining neutrality according to the terms of Anna Freud (1966)—that is, as a stance equidistant from id, ego, and superego positions, maintaining vigorous interest in all three. The involvement and participation of the members of a psychotherapy group facilitates the group leader’s ability to maintain healthy neutrality and to contain the impulses to avoid neutrality in favor of judgment therapy, which may perhaps be open to him. The bulk of the literature on neutrality is confusing and contradictory. Neutrality tends to be defined by what it is not. Therapists are told that it is not indifference, coldness, remoteness, or blandness; it is not an armed truce or a lack of concern and devotion to the patient. It is further described as not taking action when abstaining is better; it is not making judgments or at least not imposing them on the patient. It is not giving advice.

Finally, the patient’s problems emerge and are available for analysis in the interpersonal world of the group. When they do, the patient can make use of the interpersonal responses, which are not apt to be neutral at all; taken together, however, all the group’s responses allow for a neutral interpretation on the part of the therapist.

Adopting this position informs the work of group clinicians and the control they exert on the treatment by virtue of how active or passive, how verbal or reticent, how interactive or reflective, how directive or nondirective to be—in the group or with any given patient.

In the early phase of the pregroup negotiation for treatment, the therapist must do quite a lot—actively and directly—in order to establish the contract, or the frame of the therapy.The clinician’s tasks and responsibilities are numerous at this stage and form the indispensable basis for rapport and negotiation with the patient. These tasks range from the mundane—such as greeting the patient with respect—to setting the time and fee structure and arranging the details about third-party payment; they also include the task of providing more sophisticated explanations of the way this kind of treatment works, such as explaining the fundamental rule of free association and the importance of dreams.

Obviously, the role of the clinician here is more active and verbal. Lack of clarity or explicitness on the part of the clinician will interfere with the analytic work and confuse the impact of the clinician’s more neutral stance later. After the contractual parameters are well established, a phenomenon sometimes to referred to as the therapeutic envelope enfolds the members of the group in a sense of cohesion. Then the clinician’s work is to stay out of the way, to sit still, and to allow the patient and the group to lead the way.

After the therapeutic envelope, or early cohesive stability, is intact, then the work of unfolding can begin. At this point, the patient and the group together are the composers of the aria, and the conductors of the orchestra. The clinician is more appropriately like the critic of the orchestra—listening with a hovering attention to the overall themes and caring less about the notes than about the music. As is the case with any critic, the analyst is quiet, but hardly passive. He or she is listening very intensely and is actively making links and associations that are personal and stimulated by the productions of the patient. Furthermore, the clinician is carefully monitoring the self, avoiding any acting out on his or her part that may compromise the best interest of the therapy group and any given patient.

Contraindications for the Analytic Stance

Of course there are situations in which the inactive stance must be abandoned—for the safety of the patient or of others involved with the patient’s life; when this occurs, psychodynamic treatment is in effect temporarily suspended, and safety considerations must take precedence.When the patient’s ego is restored to a measure of intactness to tolerate the anxiety of an uncovering therapy, the analytic work can then resume.

Working With Shame in Groups

Clinicians frequently worry about the shaming aspects of the disclosure that are part and parcel of the work in the group. It is true that going public with one’s problems can be a daunting goal; after it has been done, however, shame is reduced, the patient begins to understand that he or she is part of the human condition and not subhuman or suprahuman, and development can resume. The group therapist sets the stage for the work of the group by developing a climate that is respectful, that avoids undue shaming of any one member by underscoring the universal quality of all human pain, and by encouraging frankness and empathic confrontation of the members by one another.

Because earliest shame is experienced in autistic isolation, the communication of it in an emotional field with another person occurs rarely and sometimes only serendipitously. Thus, the shame continues to flourish in an encapsulated, protected bubble. The bearer can neither expose it for fear of generating greater shame, nor can he or she work it through alone. As with other painful experiences, that which remains unspoken can more easily be repressed—or at least suppressed. Furthermore, should the individual have been exposed too early and too severely to repeated mortifications, then these experiences become a reservoir for humiliation. Because shame is related to the real or imagined loss of the object, the externally enforced constancy of the membership lends courage and the possibility of reestablishing empathic contact if that has been perceived as broken or withdrawn. This constancy provides the opportunity for a corrective emotional experience at its finest—not contrived, but negotiated and maintained by the goodwill of the group and the group ego as evidenced in the group contract. Thus, when empathic contact is broken—as it is repeatedly in a hard working group—there is an external, face-saving reason to come back and try again and again. The repetition compulsion is converted into working through with the continual analysis of the characterological dilemmas of each patient.

Countertransference Pressures in the Analytic Group

Perhaps the more challenging tasks for the analytic group therapist have to do with maintaining a clinical equilibrium in the face of his or her own exposure to the contagious forces of the group. It is more difficult to hold to a quiet, nonactive therapeutic stance in a group, even for the analyst who is quite able to do so in dyadic treatment. The nongratifying, inactive clinician is subject to a variety of pressures that threaten to compromise even the most committed devotee to the theory of this technique. The pressures come from internal anxiety in the clinician, interpersonal pressure from colleagues, administrative pressures, and fashion.

If one avoids action and listens carefully to the pain of the patient in therapy, there will inevitably arise more areas of identification with the patient than the therapist might be comfortable to acknowledge and to bear. The wish then arises to heal the patient quickly and also to heal the self vicariously— a natural and healthy instinct in itself. However, if the combined pain is too great, the therapist will be tempted to take action to palliate the symptoms, if only to avoid even greater levels of regression and exposure to deeper levels of conflict for the whole group.

Even if a clinician is well established and working in a thriving private practice, the inevitable periodic discouragement that is part and parcel of the therapist’s work can lead to a wish and a temptation to speed up the process, make the practice of psychotherapy more exciting, and generate more action in the hours. If, in addition, one is employed in a clinic or in a general hospital with colleagues from related fields who would like to see fast results, the difficulties with the less active stance multiply.

Furthermore, the fear of malpractice suits has added anxiety to already overburdened practitioners and has forced them to think more pragmatically. This situation makes it harder to have the courage for open-ended exploration, which is always accompanied by inevitable regressions.

Inpatient Group Therapy

In many regards, groups in an inpatient hospital setting are like those outside the hospital. There are, however, important differences: Patients in the hospital are by definition disturbed enough to require confinement away from their homes and communities. With the increasing limitations of insurance coverage, patients may be in the hospital for only a few days and may not be there voluntarily. Group membership is likely to be much less controlled than it is in an outpatient setting because patients from different races, classes, cultures, ages, and diagnostic categories are apt to be on a unit at any given time.

In any given hospital, the groups are serving a patient population that includes chronic as well as acutely psychotic patients; decompensated, personality disordered patients; substance-abusing and dual-diagnosis patients; acutely depressed and suicidal patients; and patients from a forensic population. Lengths of stay are generally brief but may range anywhere from 24 hours to several months on the same hospital unit. Private and general hospitals with psychiatric units are usually quite short-term, and state psychiatric hospitals no longer routinely keep patients for lengthy periods of time; many stays are significantly less than a year. In general, most inpatient units are locked; very few maintain an open-door policy. Many of the patients in a typical hospital have been involuntarily hospitalized, a process that varies from state to state but in all cases allows hospitals to keep a patient against his or her will for a period of a few days, with the option for the hospital to apply to the local courts to legally commit the patient to the hospital for care. Other patients are receiving treatment voluntarily, and some may be in the hospital as an alternative to some other type of legal confinement—as in the case of some substance abusers. On some hospital units, patients are separated according to one criterion or other: diagnosis, severity of illness, and presence or absence of addiction, age, or gender. In other settings, patients from many or all of these categories coexist on the floor.

A psychiatric hospital unit is a great leveler of people. Patients come from all walks of life, have any sharp or potentially dangerous belongings removed from them, are checked every 15 min, may or may not be permitted to leave the unit, and in any event must ask permission to do so from someone with a key. Added to this humiliation is the stress of whatever life problems brought them to require such confinement in the first place. Whatever the modality or theory behind it, then, the goal of the hospitalization is to return people to whatever minimum level of functioning will permit them to live outside the locked doors. In some ways, this goal represents a change in thinking about the purpose of hospitalization that has occurred over the past couple of decades. It places more emphasis on outpatient treatments to provide for and accomplish significant, lasting change in a person’s illness and life circumstances—a task that many hospitals sought to accomplish in years past. The question of whether this change is for better or for worse has been the source of much controversy, and in many hospitals the goals of the groups and other treatments provided are less than crystal clear. Differing opinions on this issue between and within members of various disciplines can make for a richly diverse or a fractious environment in which to help patients recover.

Partial hospitals are a natural outgrowth of inpatient hospitals—particularly in this age of decreasing lengths of inpatient stays. A partial hospital—like its sibling, the day treatment facility—is an intensive outpatient program that functions in a way similar to that of the daytime schedule of the inpatient unit (the term day treatment has come to imply a longer-term, more chronic program than does the partial hospital, which is generally 2–6 weeks in length). Typically, the patients in the partial hospital today were on the inpatient unit yesterday or are not quite acute enough for a locked setting, despite being in crisis. A patient in partial hospital attends community meetings and groups and then returns home in the evening and on weekends. There is limited medical and nursing attention, and the primary focus of the stay is that of ameliorating the patient’s psychological distress. This arrangement differs from the hospital stay, which has as its focus (on an acute unit) the return of the patient to medical safety and stability; by and large, this translates to the resolution of acute psychoses and suicidal crises.

Types of Inpatient Groups

Inpatient settings typically employ a variety of groups: educational, activity, behavioral, psychotherapy, and others, such as the community meeting. Each type of group serves both a specific and a more general purpose in the treatment of hospitalized patients.

Educational Groups

These groups typically include information on medications, diagnoses, and conditions encountered by patients. They are generally led in a didactic fashion, sometimes with room left for members to ask questions or share some of their own experience. These groups are based on the premise that increasing the information available to a patient about an anxietyladen topic helps to alleviate the anxiety he or she feels. Many hospitals use educational groups to help introduce patients to discussions of traumatic experiences in a structured manner. Because talking about traumas can be affectively flooding and retraumatizing to patients, educational groups are frequently used to help very disturbed patients safely begin work in these areas.

Activity Groups

Activity groups usually involve some kind of physical action, such as craft projects, music, cooking, or calisthenics. They may also be organized around daily activities that are often abandoned in the hospital—for example, a beauty group in which patients are helped to attend to specifics of grooming, such as manicures, makeup, or hairstyling. For many hospitalized patients, daily activities have been anything but normal for some time, and many may have been unable to accomplish even simple tasks because of the interference of psychiatric symptoms (positive or negative). For the most regressed inpatients, an hour of having their hair brushed, putting on nail polish, drawing a picture in the company of others, or encountering and interacting with an animal (in the case of pet therapy) may be a highly significant event. In addition, activity groups allow the healthier patients to help the sicker ones, and they allow all the patients to access competencies that can otherwise be left behind the locked doors of the hospital.

Behavioral Groups

Behavioral groups and cognitive-behavioral groups include skills training in areas such as communication, stress management, addictions, and management of self-injurious behaviors. These groups tend to be quite focused and may employ verbal or written exercises and homework outside the sessions. Such groups can be very helpful in allowing patients to gain greater control over their actions in an immediate way and can offer a language and framework in which to conceptualize the problems that may have led them to need hospitalization and therapy. Such groups are frequently used to introduce or reinforce cognitive-behavioral techniques for the management of anxiety and other overwhelming affective symptoms.

Psychodrama

Psychodrama is another type of group used in inpatient settings. Introduced by Moreno in the 1920s, psychodrama involves the enactment of a patient’s conflicted relationships on a stage, using other patients and staff to play the parts of the various members of that patient’s social world. Patients are thus able to see their conflicts played out in front of them, given opportunities to rework and modify their interactions, and experience some of the emotions involved in a structured, contained setting.

Psychotherapy Groups

Psychotherapy groups are most analogous to psychodynamic outpatient groups and may occur several times weekly. Opinions vary as to the appropriate goals and nature of such groups in this setting: Some theorists propose that it is the group itself that offers healing, and for others it is the individual interactions within the group. Kibel (1993) describes the overarching goal for an inpatient group as that of increasing the treatment alliance between staff and patients. He advocates for inclusive group membership (excepting only the most disruptive or cognitively impaired patients) and a focus on helping patients improve relatedness, reality testing, and management of affects by helping them understand their experience in the milieu. Yalom’s (1983) nondynamic model is one of here-and-now, interpersonal learning that aims to help patients identify problem behavior and learn to manage it with their anxiety. Rice and Rutan (1987) defined a psychodynamic model predicated on the idea that even the most psychotic communications and behaviors have meaning in their context and that the task of the group is to help patients understand their fears and conflicts sufficiently to enable them to use defenses that are healthier than the ones that have currently broken down. They advocate dividing the population into higher- and lower-functioning groups in order to best address the needs of the members.

Brabender and Fallon (1993) describe several models of inpatient group psychotherapy and advocate for careful matching of the inpatient system to the group model chosen by the therapist. They include such factors as the clinical mission of the hospital setting, the theoretical orientation of the unit and its leaders, and the pace of turnover of patients and staff in making their determinations as to choice of group model. Along with these factors, considering the patient population served and the value placed on groups by the institution helps group therapists to run successful groups on inpatient units. Each of the seven group models they describe (educative, interpersonal, object relations–systems, developmental, cognitive-behavioral, problem solving, and behavioral–social skills training) has its own theoretical underpinnings and technical aspects. Additionally, although each model can be placed within a framework of psychodynamic or psychoanalytic understanding, training in psychodynamics is not necessary to successfully lead groups in all of the models; this is especially helpful in institutions in which most group leaders are trainees who may have had little or no such theoretical instruction before coming to the hospital.

The Change in the Model

The literature on inpatient group psychotherapy can be confusing to those entering the field in the new millennium. The vast majority of it was written more than a decade ago, and many readers conducting inpatient groups in today’s hospitals express frustration at the difference between the hospital units described in the literature and their own. Most notably, the ascendance of the insurance review to a primary place in the treatment planning for hospitalized patients has resulted in a significant shift in clinical thinking. One of the most common questions asked in daily rounds is often What will one more day benefit this patient that he could not get elsewhere?

Such an approach can easily be seen as lending support, however irrationally, to the idea that medications are the only real benefit being offered a person who is hospitalized; yet as Kay Redfield Jamison, a psychologist with bipolar disorder, put it, “what good are medications when 40–50% of bipolar patients won’t take them?” (personal communication, September 28, 2000). The change in insurance management has meant that often, doctors spend much of their time justifying treatments to reviewers in the form of lengthy paperwork and telephone calls. Group therapy in hospitals is more essential than ever if patients are to feel a sense of purpose in regaining control in their lives and to rise above the sea of hopelessness that threatens inpatient treaters and their patients alike. Stanton and Schwartz (1954) explained half a century ago that on an inpatient ward, confusion at the top of the administrative ranks is felt by everyone, including the most deluded and psychotic patient. The interpersonal, educative, and compassionate factors in group psychotherapy remain essential tools to help patients make use of the other treatments, including medications, that may help them live happier, less hospitalized lives.

The Goal of Inpatient Psychiatric Groups

If the goal of a hospitalization is to achieve safety from harm, then the goal of the treatments within the hospital is to ameliorate unbearable pain. Medications provide some relief from the most acute symptoms, and their purpose is easy to understand. Individual meetings with a doctor help clarify the direction and nature of the hospital stay and offer some of the benefits of a short-term, individual therapy. The therapeutic action of inpatient groups occurs at many levels. Like other types of groups, they provide an enclosed arena for the reworking of recent and long-standing difficulties, and they offer an opportunity to help others on their journeys as well. Unlike many other treatments available in the hospital, the purpose of group therapy is sometimes harder to explain to acutely ill patients; this is especially true when people have been less exposed to psychological customs because of cultural, educational, or socioeconomic factors.

Patients in the hospital are often unable to articulate the nature of their difficulties and in many cases identify primarily external factors that cause them grief. More often than not, these groups are comprised of people with brittle, failing defenses—in an acute crisis. Inevitably, members are faced with a profound injury, humiliation, or loss that accompanied them to the hospital. It is unlikely that a psychotic patient who is experiencing command hallucinations and who believes he is being poisoned by the Nixon administration will enter a group for the stated purpose of reworking old psychic conflicts. Such a patient is far more likely to arrive in the group and explain to you his beliefs (or his confusion) about why he is here and what is wrong with the world outside. Attempts to direct him otherwise may be highly upsetting to him. Additionally, his neighbor in the group probably has her own ideas about what is dangerous in the world and about what is and is not true.

Accordingly, there are both explicit and implicit therapeutic agents in an inpatient group. After patients are safe and contained within the larger group setting of the hospital unit, the first task of the group is to allow members to tolerate being in the group. By and large, patients are in the hospital because they cannot tolerate being around others or because others cannot tolerate being around them. In the microcosm of the hospital ward, patients are continually attempting the impossible or the unlikely—coexisting relatively peacefully, with no one destroyed as a result. The manifest content of these groups is quite different from that of a high-functioning, outpatient group: Many members do not speak at all, some speak incomprehensibly, and others carry on seemingly intact conversations in their midst. There is often a focal subject to the group, such as a physical task or a conversational topic. The stated goal may be psychoeducational or perhaps behavioral, but the implicit goal is to help patients tolerate their own and others’ presence in the group. This goal is accomplished through shared learning of the rules of the unit, comparison of medications and symptoms, complaints about various hospital limitations, and so on. Through these learning experiences, patients begin to form a sense of themselves as a group with similar needs to be cared for.

In terms of group development, inpatient groups are generally preoccupied with the very earliest tasks because members are acutely ill and only stay a short time on the unit. These tasks are centered on dependency needs and conflicts as members come to terms with their presence in the hospital and grapple with whether the staff can save them. The development of these groups occasionally extends to include a reactive phase (Jones, 1953), in which members begin to emphasize their differences and dissatisfaction with the group leadership. Group action at this stage indicates the establishment of clearer boundaries between self and other, and it may be seen in partial or longer-term hospital groups more often than it is on the short-term inpatient ward.

Partial and longer-term hospital groups function in a way very similar to that of short-term inpatient groups, with some important exceptions. Depending on the length of stay and the severity of the population’s pathology, partial hospital groups can expect to achieve greater cohesion and developmental progress than can groups in a very short-term hospital. Similarly, longer-term hospital settings such as state institutions, where patients may stay 3–6 months or more, offer opportunities for considerable stability in groups and the potential for long periods of productive group work.

Who Leads Inpatient Groups?

Anyone who works on the inpatient unit in a clinical capacity may run a group, and hospitals vary as to the structure and organization of these roles. Psychiatrists and psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists, nurses, counselors, and trainees all may lead groups, which provides an opportunity for members of the different disciplines to work together to help their patients. In many hospitals, groups are led by teams of one senior and one junior clinician, often a trainee. Coleadership offers therapists the support and camaraderie of another person in the trenches of the work, which can be difficult and stressful. It also adds complicating factors of its own: For instance, is one leader more in charge than the other? How will the roles be divided? What will patients be told about the coleadership arrangement?

Whatever the specifics of the coleadership arrangement, it is essential that the boundaries be explicit and that the leaders be prepared to discuss the process of their coleadership as an element of the group dynamic. Possible formats for group coleadership include having one leader’s function as that of silent observer, one person as the leader and the other as the assistant, equal leadership, or alternating roles for leaders in the group. Coleadership introduces to the group elements of competition, dominance and submission, and negotiation (among others) that individual group leadership does not.

Whatever the theoretical model, group functioning depends on some sort of contract between patient, group leader, and hospital unit. Often, this contract is presented in the form of a brief, introductory statement at the beginning of each group session. Elements of the contract for an inpatient group by necessity differ some from those for an outpatient group; however, essential to any group is a contract that covers the boundaries of time, place, expectations of privacy, and attendance and participation. Whatever the theoretical model for inpatient group psychotherapy, attendance to the boundaries of the group is essential. Nevertheless, many inpatient group leaders find a lack of regard for these boundaries from busy medical and nursing staff, who may interrupt groups to handle other matters with patients during the group time. When there is limited institutional support for groups on a unit, group leaders find themselves called upon to provide the maximum possible degree of stability and safety within whatever frame actually exists in the setting. Although attendance at groups may be a requirement for privileges on some units, participation in psychotherapy groups should be fully voluntary, and in some cases, it may best be considered a privilege in itself. Unlike other groups, a psychotherapy group places demands on patients to speak in a relatively unstructured setting.

Technical Considerations

Exactly how one leads groups on an inpatient unit depends on a number of factors. Length of stay, type of population, unit philosophy, and unit structure all contribute to the overall atmosphere of the hospital ward. Choosing the best group therapy model for a particular hospital unit depends on these elements as well as on the degree of progroup culture that exists in the ward at large (Brabender & Fallon, 1993). Some of the models Brabender and Fallon describe are best in a longer-term setting, in which groups can become more cohesive, whereas others can be used even in settings in which patients turn over very rapidly. The educative model, which has as its goal helping patients comprehend their problematic styles of coping so that they can modify them, is one model that is adaptable to the very short-term unit, as is the object relations–systems theory model. The techniques used in each model are different and based on varying theoretical underpinnings.

In the educative model, maladaptive behaviors are the target of the intervention; this is not a didactic model, but rather one in which the here-and-now behaviors of the group members are used as illustrations of members’ interpersonal, behavioral style. In the educative group, members “learn to think clinically so that they can more effectively manage the sequelae of their mental illnesses” (Brabender & Fallon, 1993). Patients are directed to focus on those issues that brought them into the hospital and are encouraged to help each other understand where their coping skills and defenses break down. This is accomplished through a largely exclusive focus on events occurring within the group session. The group therapist has three tasks in this group: maintaining the boundaries of time, place, and so on; teaching patients to help one another identify and correct counterproductive behaviors; and facilitating the development of group norms such as the focus on the here and now, ensuring that group time is shared by members, and organizing discussions to be relevant to target behaviors.

In contrast, the object relations–systems group approach views the therapy group as a subset of the larger ward group (which is, in turn, a subset of the hospital as a whole). Group interventions are targeted at members’ reactions to events on the unit or hospital overall. The theoretical assumption is a psychodynamic view: Inpatients, who are mostly psychotic or borderline patients, have regressed to the point at which they are no longer able to use splitting as an effective defense to keep good and bad representations separate. The defenses used by regressed patients are mostly projection and projective identification, and they have lost the ability to maintain separateness between good and bad, self and other. This problem is manifested as fears about aggression and negative affects, and patients tend to fear retaliation if they speak about their anger and frustration. This group model is predicated on the belief that helping patients articulate negative affect in a manageable way and demonstrating the absence of retaliation from such appropriate expression allows patients to regain the capacity for healthy splitting and thus to be more psychically intact.

The group leader in this model has the task of helping patients link their experiences to events that may have affected them on the unit. Here, it is essential that the leader be aware of what has been happening on the ward so that he or she can assist patients in seeing the ways in which their reactions—in context—are amplifications of ordinary responses to stressors that have a reasonable basis in normalcy.This group model allows even the most bizarre communications from patients to be used as valid information about tensions, frustrations, and fears of retaliation from authority within the system or its subset. The role of the group leader is to help patients speak what they fear is unspeakable, using the medium of the group as a whole (the ward) to help illustrate safe ways to articulate negative experiences. Interventions in this type of group may be directed to the individual or the group as a whole, and care is taken to support members’ safe expression of difficult affect while avoiding interactions that might promote humiliation or greater vulnerability in the group. In contrast to the educative model, wherein members are asked to focus on behaviors that brought them into the hospital, the object relations–systems model avoids such direct focus as being too regressive. Instead, these interventions are directed toward reestablishing the successful defense of splitting through the tolerated expression of members’negative affects.

Current Outpatient Group Research

Focus on Efficacy, Applicability, and Efficiency

For much of the last quarter of the twentieth century, group therapy researchers have been preoccupied with demonstrating the efficacy of group therapy. They have used methodology and designs commonly used by individual therapy researchers to attempt to demonstrate that group therapy achieves clinical improvements that exceed control conditions (e.g., patients waiting for group therapy). In addition, group therapy researchers have been particularly interested in demonstrating that group therapy is as efficacious as individual therapy and is applicable to as many different types of patient problems. They have argued that if group therapy can be shown to be as efficacious and as applicable as individual therapy, it can also be shown to be more efficient (economical). In general, group therapy researchers have been successful in these pursuits.

Evidence for Efficacy and Applicability

In 1980, Smith, Glass, and Miller published an extensive review of 475 controlled studies of psychotherapy outcome. They used the method known as meta-analysis. In meta-analysis, the outcome for each measure in a study is represented by a common unit known as an effect size. After they are calculated, effect sizes can be averaged across studies to arrive at general conclusions regarding the efficacy of different types of therapy. The two findings for which their review has become well known are (a) psychotherapy is clearly effective compared to control conditions, and (b) there are minimal differences in the effectiveness of different types of psychotherapy. It is important to advocates of group therapy to know that almost half of the 475 studies involved group therapy and that the average effect size for group therapy was .83, which was almost identical to the average effect size for individual therapy, which was .87. Thus, on average, both were similarly effective. It should also be noted that most therapies were brief, which tends to characterize both the group and the individual outcome research literature. The average number of hours of therapy was 16 and the average duration of therapy was 11 weeks.

One limitation of their review was that each controlled study usually included group therapy or individual therapy but not both.Thus, differences between the studies could have influenced the comparisons that were made. In response to this problem, Tillitski (1990) conducted a meta-analysis based only on studies that included group therapy, individual therapy, and a control condition. He reported equivalent effect sizes for the two types of therapy. More recently, McRoberts, Burlingame, and Hoag (1998) published a similar review that used a larger number of studies and that used improved methodology. They also reported equivalent effect sizes for group and individual therapy.

A number of other reviews of group and individual therapies, some meta-analytic and some not, have been published during the past 20 years. In their book, Handbook of Group Psychotherapy, Fuhriman and Burlingame (1994) discussed 22 reviews. They reported that “the general conclusion to be drawn from some 700 studies that span the past two decades is that the group format consistently produced positive effects with diverse disorders and treatment models” (p. 15). From their perspective, there is considerable evidence for the efficacy of group therapy and its similarity to the efficacy of individual therapy. They also emphasized that most group therapies that have been studied are brief in duration.

In 1996, Piper and Joyce published a more recent review that examined the efficacy of time-limited, short-term group therapies and focused on 86 studies. In general, the methodology of the studies was strong. Most groups focused on a specific problem. They covered a wide range of problems, including lifestyle problems (e.g., smoking, drinking, social dysfunction); medical conditions (e.g., cancer); mood, anxiety, eating, and personality disorders; traumatic life experiences (e.g., abuse, loss); and anger control. There was also a diversity of theoretical and technical orientations, including behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, psychodynamic, psychoeducational, and others. The average length of the group therapies was 10 weeks. Each of the studies included multiple outcome variables. Thus, each study could provide more than one type of outcome evidence. Of the 50 studies that included a time-limited group therapy versus control condition comparison, almost all, 48 (96%), provided some evidence of significantly greater benefit for the therapy condition. Only one (2%) study provided evidence of greater benefit for the control condition. When this comparison was examined for each of the nine different categories of patient problems, the results were uniformly similar. For each category, nearly all of the studies provided evidence for the superiority of the therapy condition. Of the six studies that included a time-limited group therapy versus individual therapy comparison, only one provided evidence of superiority for the group therapy and only one provided evidence of superiority for the individual therapy. In contrast, all six provided evidence of no difference in benefit. Overall, the results of the review were consistent with those of previous reviews. There was clear evidence that short-term group therapies of different theoretical and technical orientations offered clinical benefits across a diverse range of patients, and approximately equivalent results were obtained for group and individual therapy. The authors concluded that the evidence for the efficacy and the applicability of time-limited group therapy was substantial.

Evidence for Efficiency

In regard to the question of efficiency, Toseland and Siporin (1986) focused on studies that included both group therapy and individual therapy in the same study. Of 12 investigators who addressed the question of efficiency, 10 concluded that group therapy was more efficient. It seems clear that if one restricts the definition of efficiency to the average amount of time required to treat each patient, a clear figure can be calculated for each of the two therapies, and a straightforward comparison can be made. For example, in 1984, Piper, Debbane, Bienvenu, and Garant investigated four forms of psychotherapy: short-term individual, short-term group, long-term individual, and long-term group. Short-term was defined as 24 sessions over 6 months, and long-term was defined as 96 sessions over 2 years. Individual therapy was provided in sessions that lasted .9 hours, and group therapy was provided in sessions that lasted 1.5 hours. Groups consisted of eight patients. The time required per patient from the perspective of the therapist can be calculated for each therapy. For example, from the perspective of the therapist, short-term group therapy, which required 4.5 hours per patient, was more efficient than short-term individual therapy, which required 21.6 hours per patient, in a time ratio of approximately 1:5. Another example of the efficiency associated with short-term group therapy comes from a program that provides treatment for psychiatric outpatients who experience difficulty adapting to the loss of one or more persons (Piper, McCallum, & Azim, 1992). A loss group meets once a week for 90 min for 12 weeks. It is possible to compare the average amount of therapist time allocated to each patient in a loss group with the average amount of therapist time allocated to a patient in short-term individual therapy. Based on an average of 7.5 patients in a group for twelve 90-min sessions, the average time per patient is 2.4 hours. For one patient in individual therapy for twelve 45-min sessions, the average time per patient is 9.0 hours. The ratio is approximately 1:4; this means that about four times as many patients can be treated in a group therapy program for loss. Of course, other factors such as compliance and outcome need to be taken into account in evaluating the overall success of the two types of therapy, but when therapist time is the criterion, the examples indicate that group therapy is more efficient.

More Complex Questions

Overall, the findings concerning efficacy, applicability, and efficiency suggest that for a wide range of disorders, group therapy is as effective as individual therapy and that it is more efficient. In regard to practice, there is the clear implication that group therapy rather than individual therapy should be the treatment of choice for many disorders that have been studied. Although this conclusion is important, reviewers of group therapy research (e.g., Bednar & Kaul, 1994) have criticized researchers for being too preoccupied with issues of efficacy, applicability, and efficiency, to the exclusion of other important areas of research. These areas include efforts to answer the following questions:

- What types of patients benefit more from different types of group therapy? Patient types include personality, demographic, and diagnostic differences. Group therapy types include theoretical, technical, and duration differences.

- What types of patients benefit more from group therapy or individual therapy?

- What types of therapist characteristics and interventions lead to greater benefit?

- What underlying mechanisms are responsible for therapeutic change?

- What factors are responsible for maintenance of improvement?

These are indeed important questions whose answers would advance knowledge in the field. The question of why group therapy researchers have neglected such questions in favor of continuing to conduct studies that address efficacy, applicability, and efficiency is a legitimate one that requires an answer.

Resistance to Group Therapy

Despite the evidence and the positive attributes associated with group therapy, it is not a readily embraced form of treatment; an indication of this was reported by Budman et al. (1988), who conducted a study that compared time-limited group therapy and time-limited individual therapy for psychiatric outpatients. These investigators found significant improvement for patients in both types of treatment. However, they also found that patients tended to prefer individual therapy. Other formal and informal reports in the literature suggest that if they are given the choice, many patients and many therapists would choose individual therapy.