Sample Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

From the time that modern views of mental illness emerged in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, significantly less attention has been given to mental health problems in children than it has to problems in adults (Rie, 1971). Even today there are far fewer categories for diagnosing mental disorders in children, and these categories vary in their sensitivity to developmental parameters and context. Current knowledge of child and adolescent disorders is compromised by a lack of child-specific theories, by an unsystematic approach to research (Kazdin, 2001), and by the inherent conceptual and research complexities (Kazdin & Kagan, 1994), which may explain why there are far fewer empirically supported treatments for children than for adults (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Despite these caveats, tremendous advances have been made over the last decade (Mash & Barkley, 1996; Mash & Wolfe, 2002; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

New conceptual frameworks, new knowledge, and new research methods have greatly enhanced our understanding of childhood disorders (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995; Sameroff, Lewis, & Miller, 2000) as well as our ability to assess and treat children with these problems (Mash & Barkley, 1998; Mash & Terdal, 1997b).

We begin with a discussion of the significance of children’s mental health problems and the role of multiple interacting influences in shaping adaptive and maladaptive patterns of behavior. Next we provide a brief overview of disorders of childhood and adolescence and related conditions as defined by current diagnostic systems (American Psychiatric Association;APA, 2000). We then consider two common categories of problems in children and adolescents: externalizing disorders (disruptive behavior disorders; attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, ADHD), and internalizing disorders (mood disorders, anxiety disorders). We illustrate current issues and approaches to child and adolescent disorders by focusing on ADHD and anxiety disorders as examples. In doing so we consider the main characteristics, epidemiology, developmental course, associated features, proposed causes, and an integrative developmental pathway model for each of these disorders. We conclude with a discussion of current issues and future directions for the field.

The Significance of Children’s Mental Health Problems

Long-overdue concern for the mental health of children and adolescents is gradually coming to the forefront of the political agenda. For example, in the United States the new millennium witnessed White House meetings on mental health in young people and on the use of psychotropic medications with children. ASurgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health resulted in an extensive report and recommendations (U.S. Public Health Service, 2001a), closely followed by a similar report on youth violence (U.S. Public Health Service, 2001b). Increasingly, researchers in the fields of clinical child psychology, child psychiatry, and developmental psychopathology are becoming attentive to the social policy implications of their work and in effecting improvements in the identification of and services for youth with mental health needs (Cicchetti & Toth, 2000; Weisz, 2000c). Greater recognition is also being given to factors that contribute to children’s successful mental functioning, personal well-being, productive activities, fulfilling relationships, and ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000; U.S. Public Health Service, 2001a).

The increase in attention to children’s mental health problems derives from a number of sources. First, many young people experience significant mental health problems that interfere with normal development and functioning. As many as one in five children in the United States experience some type of difficulty (Costello & Angold, 2000; Roberts, Attkisson, & Rosenblatt, 1998), and 1 in 10 have a diagnosable disorder that causes some level of impairment (B. J. Burns et al., 1995; Shaffer et al., 1996). These numbers likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem because they do not include a substantial number of children who manifest subclinical or undiagnosed disturbances that may place them at high risk for the later development of more severe clinical problems (McDermott & Weiss, 1995).

Moreover, the frequency of certain childhood disorders— such as antisocial behavior and some types of depression—may be increasing as the result of societal changes and conditions that create growing risks for children (Kovacs, 1997). Among these conditions are chronic poverty, family breakup, single parenting, child abuse, homelessness, problems of the rural poor, adjustment problems of immigrant and minority children, and the impact of HIV, cocaine, and alcohol on children’s growth and development (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994; McCall & Groark, 2000). Evidence gathered by the World Health Organization suggests that by the year 2020, childhood neuropsychiatric disorders will rise proportionately by over 50% internationally—to become one of the five most common causes of morbidity, mortality, and disability among children (U.S. Public Health Service, 2001a).

For a majority of children who experience mental health problems, these problems go unidentified—only about 20% receive help, a statistic that has not changed for some time (B. J. Burns et al., 1995). Even when children are identified and receive help for their problems, this help may be less than optimal. For example, only about half of children with identified ADHD seen in real-world practice settings receive care that conforms to recommended treatment guidelines (Hoagwood, Kelleher, Feil, & Comer, 2000). The fact that so few children receive appropriate help is probably related to such factors as inaccessibility, cost, parental dissatisfaction with services, and the stigmatization and exclusion often experienced by children with mental disorders and their families (Hinshaw & Cicchetti, 2000).

Unfortunately, children with mental health problems who go unidentified and unassisted often end up in the criminal justice or mental health systems as young adults (Loeber & Farrington, 2000). They are at a much greater risk for dropping out of school and for not being fully functional members of society in adulthood, which adds further to the costs of childhood disorders in terms of human suffering and financial burdens. For example, average costs of medical care for youngsters with ADHD are estimated to be double those for youngsters without ADHD (Leibson, Katusic, Barberesi, Ransom, & O’Brien, 2001). Moreover, allowing just one youth to leave high school for a life of crime and drug abuse is estimated to cost society from $1.7 to $2.3 million (Cohen, 1998).

Understanding Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence

Much of what we know about disorders of childhood and adolescence is based on findings obtained at a single point in the child’s development and in a single context. Although it is useful, such information is incomplete because it fails to capture dynamic changes in the expression and causal factors that characterize most forms of child psychopathology. Only in the last two decades have efforts to describe and explain psychopathology in children included longitudinal methods and conceptual models that are sensitive to developmental change and the sociocultural context (Cicchetti & Aber, 1998; Boyce et al., 1998; García Coll, Akerman, & Cicchetti, 2000).

The study of child psychopathology is further complicated by the fact that most childhood disorders do not present in neat packages, but rather overlap, co-exist, or both with other disorders. For example, symptoms of anxiety and depression in childhood are highly correlated (Brady & Kendall, 1992; Compas & Oppedisano, 2000), and there is also much overlap among emotional and behavioral disorders, child maltreatment, substance abuse, delinquency, and learning difficulties (e.g., Greenbaum, Prange, Friedman, & Silver, 1991). Many behavioral and emotional disturbances in children are also associated with specific physical symptoms, medical conditions, or both.

Furthermore, few childhood disorders can be attributed to a single cause. Although some rare disorders such as phenylketonuria (PKU) or Fragile X mental retardation may be caused by a single gene, current models in behavioral genetics recognize that more common and complex disorders are the result of multigene systems containing varying effect sizes (Plomin, 1995). Most childhood disorders are the result of multiple and interacting risk and protective factors, causal events, and processes (e.g., Ge, Conger, Lorenz, Shanahan, & Elder, 1995). Contextual factors such as the child’s family, school, community, and culture exert considerable influence, one that is almost always equivalent to or greater than those factors usually thought of as residing within the child (Rutter, 2000b).

Like adult disorders, causes of child psychopathology are multifaceted and interactive. Prominent contributing causes include genetic influences, neurobiological dysfunction, difficult infant temperament, insecure child-parent attachments, problems in emotion regulation or impulse control, maladaptive patterns of parenting, social-cognitive deficits, parental psychopathology, marital discord, and limited family resources, among others. The causes and outcomes of child psychopathology operate in dynamic and interactive ways across time and are not easy to disentangle. The designation of a specific factor as a cause or an outcome of child psychopathology usually reflects the point in an ongoing developmental process that the child is observed and the perspective of the observer. For example, a language deficit may be viewed as a disorder (e.g., mixed receptiveexpressive language disorder), the cause of other problems (e.g., impulsivity), or the result of some other condition or disorder (e.g., autism). In addition, biological and environmental determinants interact at all periods of development. For example, the characteristic styles used by parents in responding to their infants’ emotional expressions may influence the manner in which patterns of cortical mappings and connections within the limbic system are established during infancy (Dawson, Hessl, & Frey, 1994). Thus, early experiences may shape neural structure and function, which may then create dispositions that direct and shape the child’s later experiences (Dawson,Ashman, & Carver, 2000).

The experience and the expression of psychopathology in children are known to have cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioral components; consequently, many different descriptions and definitions of abnormality in children have been proposed (Achenbach, 2000). However, a central theme in defining disorders of childhood and adolescence is adaptational failure in one or more of these components or in the ways in which these components are integrated and organized (Garber, 1984; Mash & Dozois, 1996). Adaptational failure may involve a deviation from age-appropriate norms, an exaggeration or diminishment of normal developmental expressions, interference in normal developmental progress, a failure to master age-salient developmental tasks, a failure to develop a specific function or regulatory mechanism, or any combination of these (Loeber, 1991).

Numerous etiological models have been proposed to explain psychopathology in children. These models have differed in their relative emphasis on certain causal mechanisms and constructs, and they often use very different terminology and concepts to describe seemingly similar child characteristics and behaviors. Biological paradigms, for example, have emphasized genetic mutations, neuroanatomy, and neurobiological mechanisms as factors contributing to psychopathology, whereas psychological paradigms have focused on the interpersonal and family relationships that shape a child’s cognitive, behavioral, and affective development. Although each of the various models places relative importance to certain causal processes versus others, most models recognize the role of multiple interacting influences. There is a growing recognition to look beyond the emphasis of singlecause theories and to integrate currently available models through intra- and interdisciplinary research efforts (cf. Arkowitz, 1992).

Interdisciplinary perspectives on disorders of childhood and adolescence mirror the considerable investment in children on the part of many different disciplines and professions, each of which has its own unique perspective of child psychopathology. Psychiatry-medicine, for example, has viewed and defined such problems categorically in terms of the presence or absence of a particular disorder or syndrome that is believed to exist within the child. In contrast, psychology has conceptualized psychopathology as an extreme occurrence on a continuum or dimension of characteristic(s) and has also focused on the role of environmental influences that operate outside the child. However, the boundaries are arbitrarily drawn between categories and dimensions, or between inner and outer conditions and causes, and there is growing recognition to find workable ways of integrating the two different worldviews of psychiatry-medicine and psychology (Richters & Cicchetti, 1993).

Child and Adolescent Disorders: an Overview

Many of the disorders that are present in adults are also present in children in one form or another, although admittedly the pathways are complex. Even though children can have similar mental health problems as adults, their problems often have a different focus. Children may experience difficulty with normal developmental tasks, such as beginning school, or they may lag behind other children their age or behave like a younger child during stressful periods. Even when children have problems that appear in adults, their problems may be expressed differently. For example, anxious children may be very concerned about their parents and other family members and may want to be near them at all times to be sure that everyone is all right.

The APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition–Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000) recognizes the uniqueness of childhood disorders in a separate section for disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. However, this designation is viewed primarily as a matter of convenience, recognizing that the distinction between disorders in children and those in adults is not always clear. For example, although most individuals with disorders display symptoms during childhood and adolescence, they sometimes are not diagnosed until adulthood. In addition, many disorders not included in the childhood disorders section of DSM-IV-TR often have their onset during childhood and adolescence, such as depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

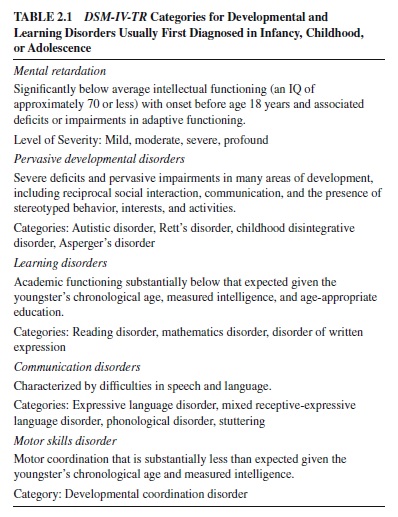

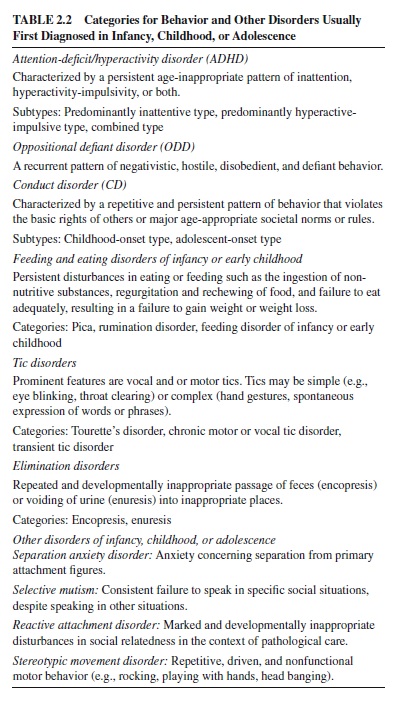

A brief overview of DSM-IV-TR disorders of childhood is presented in Table 2.1 for problems in development and learning and in Table 2.2 for behavior and other disorders. The disorders listed in these tables have traditionally been thought of as first occurring in childhood or as exclusive to childhood and as requiring child-specific operational criteria.

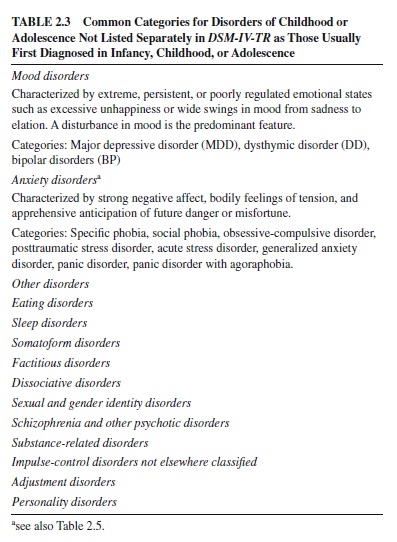

In addition to the separate listing of disorders of childhood and adolescence, many other DSM-IV-TR disorders apply to children and adolescents. As highlighted in Table 2.3, the most common of these are mood and anxiety disorders. For these disorders, the same diagnostic criteria are used for children and adults with various adjustments made based on the age-appropriateness, duration, and—in some instances—the types of symptoms.

The DSM-IV-TR distinction between child and adult categories is recognized as being arbitrary—more a reflection of our current lack of knowledge concerning the continuitiesdiscontinuities between child and adult disorders than of the existence of qualitatively distinct conditions (Silk, Nath, Siegel, & Kendall, 2000). Recent efforts to diagnose ADHD in adults illustrate this problem (Faraone, Biederman, Feighner, & Monuteaux, 2000). Whereas the criteria for ADHD were derived from work with children and the disorder is included in the child section of DSM-IV-TR, the same criteria are used to diagnose adults even though they may not fit the expression of the disorder in adults very well. Similarly, it is not clear that the degree of differentiation represented by the many DSM-IV-TR categories for anxiety disorders in adults fits with how symptoms of anxiety are expressed during childhood, which may reflect differences related to when symptoms appear in development rather than to the type of disorder (Zahn-Waxler, Klimes-Dougan, & Slattery, 2000). The more general issue here is whether there is a need for separate diagnostic criteria for children versus adults or whether the same criteria can be used by adjusting them to take into account differences in developmental level and context.

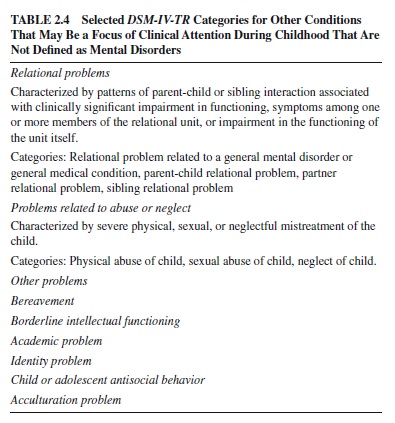

There are a number of additional DSM-IV-TR categories for other conditions that are not defined as mental disorders but are frequently a focus of clinical attention during childhood. As highlighted in Table 2.4, these categories include relational problems, maltreatment, and academic and adjustment difficulties. The relational nature of most childhood disorders underscores the significance of these categories for diagnosing children and adolescents (Mash & Johnston, 1996). Although DSM-IV-TR does not provide the specifics needed to adequately diagnose these complex concerns, it does call attention to their importance.

In the sections that follow, we consider the two most common types of child and adolescent disorders: externalizing and internalizing problems. Youngsters with externalizing problems generally display behaviors that are disruptive and harmful to others (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000). In contrast, those with internalizing problems experience inner-directed negative emotions and moods such as sadness, guilt, fear, and worry (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2000). In reality, both types of disorders have behavioral, emotional, and cognitive components, and there is substantial overlap between the two.

Externalizing Disorders: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Adhd)

Externalizing disorders are characterized by a mix of impulsive, overactive, aggressive, and delinquent acts (G. L. Burns et al., 1997). They include a wide range of acting-out behaviors—from annoying but mild behaviors such as noncompliance and tantrums to more severe behaviors such as physical aggression and stealing (McMahon & Estes, 1997). The two major types of externalizing disorders are (a) disruptive behavior disorders and (b) ADHD. We limit our discussion to ADHD and discuss its symptoms and subtypes, epidemiology, developmental course, accompanying disorders, associated features, causes, and possible developmental pathways. Many of the issues that we address in discussingADHD (e.g., prevalence estimates, comorbidity, gender and cultural factors, multiple and interacting causes, developmental pathways) have relevance for most other disorders of childhood.

ADHD is characterized by persistent and age-inappropriate symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, or both (Campbell, 2000). Children with ADHD have great difficulty focusing on demands, are in constant motion, act without thinking, or any combination of these. Views of ADHD have changed dramatically over the past century as a result of new findings and discoveries (Barkley, 1998).

Symptoms and Subtypes

The main attention deficit in ADHD appears to be one of sustained attention (Douglas, 1999). When presented with an uninteresting or repetitive task, the performance of a child with ADHD deteriorates over time compared to that of other children. However, findings are not always consistent and may depend on the definitions and tasks used to assess this construct (Hinshaw, 1994). Symptoms of hyperactivity and behavioral impulsivity are best viewed as a single dimension of behavior called hyperactivity-impulsivity (Lahey et al., 1988). The strong link between hyperactivity and behavioral impulsivity has led to suggestions that both are part of a more fundamental deficit in behavioral inhibition (Barkley, 1997; Quay, 1997).

The three core features of ADHD—inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity—are complex processes. The current view is that hyperactivity-impulsivity is an essential feature of ADHD. In contrast to inattention, it distinguishes children withADHD from those with other disorders and from normal children (Halperin, Matier, Bedi, Sharma, & Newcorn, 1992). As such, impulsivity-hyperactivity appears to be a specific marker for ADHD, whereas inattention is not (Taylor, 1995). Children with ADHD display a unique constellation and severity of symptoms but do not necessarily differ from comparison children on all types and measures of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Barkley, 1998).

DSM-IV-TR specifies three ADHD subtypes based on the child’s primary symptoms, which have received growing empirical support (Eiraldi, Power, & Nezu, 1997; Faraone, Biederman, & Friedman, 2000; Gaub & Carlson, 1997a). Children with the combined type display symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity; those with the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type display primarily symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity; and those with the predominantly inattentive type display primarily symptoms of inattention. Children with the combined and predominantly hyperactiveimpulsive types are more likely to display problems in inhibiting behavior and in behavioral persistence than are those who are predominantly inattentive. They are also more likely to be aggressive, defiant, and oppositional; to be rejected by their peers; and to be suspended from school or placed in special education classes (Lahey & Carlson, 1992). Because children who are predominantly hyperactive-impulsive are usually younger than those with the combined type, it is not yet known whether these are actually two distinct subtypes or the same type at different ages (Barkley, 1996).

Children who are predominantly inattentive are described as inattentive and drowsy, daydreamy, spacey, in a fog or easily confused, and they commonly experience a learning disability. They process information slowly and find it hard to remember things. Their main deficits seem to be speed of information processing and selective attention. Growing—but not yet conclusive—evidence suggests that children who are predominantly inattentive constitute a distinct subgroup from other two types (Maedgen & Carlson, 2000). They appear to display different symptoms, associated conditions, family histories, outcomes, and responses to treatment (Barkley, 1998).

The DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD have a number of limitations (Barkley, 1996), several of which apply to other childhood disorders as well. First, they are developmentally insensitive, using the same symptom criteria for individuals of all ages—even though some symptoms, such as running and climbing, apply more to young children. In addition, the number of symptoms needed to make a diagnosis is not adjusted for age or level of maturity even though many of these symptoms show a general decline with age. Second, according to DSM-IV-TR, ADHD is a disorder that the child either has or does not have. However, because the number and severity of symptoms are also a matter of degree, children who fall just below the cutoff for ADHD are not necessarily qualitatively different from those who are just above it. In fact, over time, some children move in and out of the DSMIV-TR category as a result of fluctuations in their behavior. Third, there is some uncertainty about the DSM-IV-TR requirement that symptoms must have an onset prior to age 7. There seems to be little difference between children with an onset of ADHD before or after age 7 (Barkley & Biederman, 1997), and about half of children with ADHD who are predominantly inattentive do not manifest the disorder until after age 7 (Applegate et al., 1997). Finally, the requirement of persistence for 6 months may be too brief for young children. Many preschoolers display symptoms for 6 months, and the symptoms then go away. These limitations highlight the fact that DSM-IV-TR criteria are designed for specific purposes—classification and diagnosis. They help shape our understanding of ADHD and other childhood disorders but are also shaped by—and in some instances lag behind—new research findings.

Epidemiology

As many as one half of all clinic-referred children display ADHD symptoms either alone or in combination with other disorders, making it one of the most common referral problems in North America (Barkley, 1998). The best estimate is that about 3–7% of all school-age children in North America have ADHD (APA, 2000; Jensen et al., 1999). However, as with other disorders, estimates can and do vary widely because informants in different settings do not always agree on symptoms or may emphasize different symptoms. Teachers, for example, are especially likely to rate a child as inattentive when oppositional symptoms are also present (Abikoff, Courtney, Pelham, & Koplewicz, 1993). Because adults may disagree, prevalence estimates are much higher when based on just one person’s opinion than they are when based on a consensus (Lambert, Sandoval, & Sassone, 1978).

ADHD occurs much more frequently in boys than in girls, with estimates ranging from 6–9% for boys and from 2–3% for girls in the 6- to 12-year age range. In adolescence, overall rates of ADHD drop for both boys and girls, but boys still outnumber girls by the same ratio of 2:1 to 3:1. This ratio is even higher in clinic samples, in which boys outnumber girls by 6:1 or more—most likely because boys are referred more frequently due to their defiance and aggression (Szatmari, 1992). ADHD in girls may go unrecognized and unreported because teachers may fail to recognize and report inattentive behavior unless it is accompanied by the disruptive symptoms normally associated with boys (McGee & Feehan, 1991). In fact, many of the DSM-IV-TR symptoms, such as excessive running around, climbing, and blurting out answers in class are generally more common in boys than in girls. Thus, sampling, referral, and definition biases may be a factor in the greater reported prevalence ofADHD in boys than in girls.

In the past, girls with ADHD were a highly under-studied group (Arnold, 1996). However, recent findings show that girls with ADHD are more likely to have conduct, mood, and anxiety disorders; lower IQ and school achievement scores; and greater impairment on measures of social, school, and family functioning than are girls without ADHD (Biederman et al., 1999; Greene et al., 2001; Rucklidge & Tannock, 2001). In addition, the expression, severity of symptoms, family correlates, and response to treatment are similar for boys and girls with ADHD (Faraone et al., 2000; Silverthorn, Frick, Kuper, & Ott, 1996). When gender differences are found, boys show more hyperactivity, more accompanying aggression and antisocial behavior, and greater impairment in executive functions, whereas girls show greater intellectual impairment (Gaub & Carlson, 1997b; Seidman, Biederman, Faraone, & Weber, 1997).

Developmental Course

The symptoms of ADHD are probably present at birth, although reliable identification is difficult until the age of 3–4 years when hyperactive-impulsive symptoms become increasingly more salient (Hart, Lahey, Loeber, Applegate, & Frick, 1996). Preschoolers with ADHD act suddenly without thinking, dashing from activity to activity, grabbing at immediate rewards; they are easily bored and react strongly and negatively to routine events (Campbell, 1990; DuPaul, McGoey, Eckert, & VanBrakle, 2001). Symptoms of inattention emerge at 5–7 years of age, as classroom demands for sustained attention and goal-directed persistence increase (Hart et al., 1996). Symptoms of inattention continue through grade school, resulting in low academic productivity, distractibility, poor organization, trouble meeting deadlines, and an inability to follow through on social promises or commitments to peers (Barkley, 1996).

The child’s hyperactive-impulsive behaviors that were present in preschool continue, with some decline, during the years from 6 to 12. During elementary school, oppositional defiant behaviors may also develop (Barkley, 1998). By 8–12 years, defiance and hostility may take the form of serious problems, such as lying or aggression. Through the school years,ADHD increasingly takes its toll as children experience problems with self-care, personal responsibility, chores, trustworthiness, independence, social relationships, and academic performance (Koplowicz & Barkley, 1995; Stein, Szumoski, Blondis, & Roizen, 1995). Although hyperactive-impulsive behaviors decline significantly by adolescence, they still occur at a level higher than in 95% of same-age peers (Barkley, 1996). The disorder continues into adolescence for at least 50% or more of clinic-referred elementary school children (Barkley, Fisher, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1990; Weiss & Hechtman, 1993). Childhood symptoms of hyperactivityimpulsivity (more so than those of inattention) are generally related to poor adolescent outcomes (Barkley, 1998). Some youngsters withADHD either outgrow their disorder or learn to cope with it. However, many continue to experience problems, leading to a lifelong pattern of suffering and disappointment (Mannuzza & Klein, 1992).

Accompanying Disorders and Symptoms

As many as 80% of children with ADHD have a co-occurring disorder (Jensen, Martin, & Cantwell, 1997). About 25% or more have a specific learning disorder (Cantwell & Baker, 1992; Semrud-Clikeman et al., 1992) and 30–60% have impairments in speech and language (Baker & Cantwell, 1992; Cohen et al., 2000). About half of all children with ADHD— mostly boys—also meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) by age 7 or later, and 30–50% eventually develop conduct disorder (CD; Barkley, 1998; Biederman, Faraone, & Lapey, 1992). ADHD, ODD, and CD tend to run in families, which suggests a common causal mechanism (Biederman et al., 1992). However, ADHD is usually associated with cognitive impairments and neurodevelopmental difficulties, whereas conduct problems are more often related to family adversity, parental psychopathology, and social disadvantage (Schachar & Tannock, 1995).

About 25% of children with ADHD—usually younger boys—experience excessive anxiety (Tannock, 2000). It is interesting to note that the overall relationship between ADHD and anxiety disorders is reduced or eliminated in adolescence. The co-occurrence of an anxiety disorder may inhibit the adolescent with ADHD from engaging in the impulsive behaviors that characterize other youngsters with ADHD (Pliszka, 1992). As many as 20% of children with ADHD experience depression, and even more eventually develop depression or another mood disorder by early adulthood (Mick, Santangelo, Wypij, & Biederman, 2000; Willcutt, Pennington, Chhabildas, Friedman, & Alexander, 1999). The association between ADHD and depression may be a function of family risk for one disorder’s increasing risk for the other (Biederman et al., 1995).

Associated Features

Children with ADHD display many associated cognitive, academic, and psychosocial deficits. They consistently show deficits in executive functions—particularly those related to motor inhibition (Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996). Most children with ADHD are of at least normal overall intelligence, but they experience severe difficulties in school nevertheless (Fischer, Barkley, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1990). In fact, the academic skills of children with ADHD have been found to be impaired even before they enter the first grade (Mariani & Barkley, 1997).

The association between ADHD and general health is uncertain at this time (Barkley, 1998; Daly et al., 1996), although a variety of health problems have been suggested (e.g., upper respiratory infections, asthma, allergies, bedwetting, and other elimination problems). Instability of the sleep-wake system is characteristic of children with ADHD, and sleep disturbances are common (Gruber, Sadeh, & Raviv, 2000). Resistance to going to bed and fewer total hours may be the most significant sleep problems (Wilens, Biederman, & Spencer, 1994), although the precise nature of the sleep disturbance in ADHD is not known (Corkum, Tannock, & Moldofsky, 1998). Up to 50% of children with ADHD are described as accident-prone, and they are more than twice as likely as other children to experience serious accidental injuries, such as broken bones, lacerations, severe bruises, poisonings, or head injuries (Barkley, 1998).As young adults, they are at higher risk for traffic accidents and offenses (NadaRaja et al., 1997) as well as for substance abuse (Wilens, Biederman, Mick, Faraone, & Spencer, 1997) and risky sexual behaviors such as multiple partners and unprotected sex (Barkley, Fisher, & Fletcher, 1997).

Families of children withADHD experience many difficulties, including interactions characterized by negativity, child noncompliance, high parental control, and sibling conflict (Whalen & Henker, 1999). Parents may experience high levels of distress and related problems; the most common ones are depression in mothers and antisocial behavior (i.e., substance abuse) in fathers. Further stress on family life stems from the fact that parents of children with ADHD may themselves have ADHD and other associated conditions (Johnston & Mash, 2001). It is critical to note that high levels of family conflict and the links between ADHD and parental psychopathology and marital discord seem to be related to the child’s co-occurring conduct problems rather than toADHD alone.

Children and adolescents with ADHD display little of the give and take, cooperation, and sharing that characterize other children (Dumas, 1998; Henker & Whalen, 1999). They are disliked and uniformly rejected by peers, have few friends, and are often unhappy (Gresham, MacMillan, Bocian, Ward, & Forness, 1998; Landau, Milich, & Diener, 1998). Their difficulties in regulating their emotions (Melnick & Hinshaw, 2000) and the aggressiveness that frequently accompanies ADHD often lead to conflict and negative peer reputation (Erhardt & Hinshaw, 1994).

Causes

Current research into causal factors provides strong evidence for ADHD as a disorder with neurobiological determinants (Biederman & Spencer, 1999; Tannock, 1998). However, biological and environmental risk factors together shape the expression of ADHD symptoms over time following several different pathways (Johnston & Mash, 2001; Taylor, 1999). ADHD is a complex and chronic disorder of brain, behavior, and development; its cognitive and behavioral outcomes affect many areas of functioning (Rapport & Chung, 2000). Therefore, any explanation of ADHD that focuses on a single cause and single outcome is likely to be inadequate (Taylor, 1999).

Genetics

Several sources of evidence point to genetic influences as important causal factors in ADHD (Kuntsi & Stevenson, 2000). First, about one third of immediate and extended family members of children with ADHD are also likely to have the disorder (Faraone, Biederman, & Milberger, 1996; Hechtman, 1994). Of fathers who had ADHD as children, one third of their offspring have ADHD (Biederman et al., 1992; Pauls, 1991). Second, studies of biologically related and unrelated pairs of adopted children have found a strong genetic influence that accounts for nearly half of the variance in attentionproblem scores on child behavior rating scales (van den Oord, Boomsma, & Verhulst, 1994). Third, twin studies report heritability estimates ofADHD averaging .80 or higher (Tannock, 1998). Both the symptoms and diagnosis of ADHD show average concordance rates for identical twins of 65%—about twice that of fraternal twins (Gilger, Pennington, & DeFries, 1992). Twin studies also find that the greater the severity of ADHD symptoms, the greater the genetic contributions (Stevenson, 1992).

Finally, genetic analysis suggests that specific genes may account for the expression of ADHD in some children (Faraone et al., 1992). Preliminary studies have found a relation between the dopamine transporter (DAT) gene and ADHD (Cook et al., 1995; Gill, Daly, Heron, Hawi, & Fitzgerald, 1997). Studies have also focused on the gene that codes for the dopamine receptor gene (DRD4), which has been linked to the personality trait of sensation seeking (high levels of thrill-seeking, impulsive, exploratory, and excitable behavior; Benjamin et al., 1996; Ebstein et al., 1996). Findings that implicate specific genes within the dopamine system in ADHD are intriguing, and they are consistent with a model suggesting that reduced dopaminergic activity may be related to the behavioral symptoms of ADHD (Faraone et al., 1999; Winsberg & Comings, 1999). However, other genetic findings indicate that the serotonin system also plays a crucial role in mediating the hyperactive-impulsive components of ADHD (Quist & Kennedy, 2001). As with other disorders of childhood, it is important to keep in mind that in the vast majority of cases, the heritable components of ADHD are likely to be the result of multiple interacting genes on several different chromosomes. Taken together, the findings from family, adoption, twin, and specific gene studies suggest that ADHD is inherited, although the precise mechanisms are not yet known (Edelbrock, Rende, Plomin, & Thompson, 1995; Tannock, 1998).

Pre- and Perinatal Factors

Many factors that compromise the development of the nervous system before and after birth—such as pregnancy and birth complications, low birth weight, malnutrition, early neurological insult or trauma, and diseases of infancy—may be related toADHD symptoms (Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Chen, & Jones, 1996; Milberger, Biederman, Faraone, Guite, & Tsuang, 1997). Although these early factors predict later symptoms ofADHD, there is little evidence that they are specific to ADHD because they also predict later symptoms of other disorders as well. A mother’s use of cigarettes, alcohol, or other drugs during pregnancy can have damaging effects on her unborn child. Mild or moderate exposure to alcohol before birth may lead to inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and associated impairments in learning and behavior (Streissguth, Bookstein, Sampson, & Barr, 1995). Other substances used during pregnancy—such as nicotine or cocaine—can adversely affect the normal development of the brain and lead to higher than normal rates of ADHD (Weissman et al., 1999).

Neurobiological Factors

There is both indirect and direct support for neurobiological causal factors in ADHD (Barkley, 1998; Faraone & Biederman, 1998). There are known associations between events or conditions known to be related to neurological status and symptoms of ADHD. Among these are peri- and postnatal events and diseases; environmental toxins such as lead; language and learning disorders; and signs of neurological immaturity, such as clumsiness, poor balance and coordination, and abnormal reflexes. Other sources of indirect support include the improvement in ADHD symptoms produced by stimulant medications known to affect the central nervous system, the similarity between symptoms of ADHD and symptoms associated with lesions to the prefrontal cortex (Grattan & Eslinger, 1991), and the deficient performances of children with ADHD on neuropsychological tests associated with prefrontal lobe functions (Barkley, Grodzinsky, & DuPaul, 1992).

Neuroimaging studies have found that children with ADHD have a smaller right prefrontal cortex than do those without ADHD (Filipek et al., 1997) and show structural abnormalities in several parts of the basal ganglia (SemrudClikeman et al., 2000). Although simple and direct relations cannot be assumed between brain size and abnormal function, anatomic measures of frontostriatal circuitry are related to children’s performance on response inhibition tasks (Casey et al., 1997). In adults with ADHD and in adolescent girls with ADHD, positron-emission tomography (PET) scan studies have found reduced glucose metabolism in the areas of the brain that inhibit impulses and control attention (Ernst et al., 1994). Significant correlations have also been found between diminished metabolic activity in the left anterior frontal region and severity of ADHD symptoms in adolescents (Zametkin et al., 1993). Taken together, the findings from neuroimaging studies suggest the importance of the frontostriatal region of the brain inADHD. These studies tell us that in children with ADHD, there is a structural difference or less activity in certain regions of the brain, but they don’t tell us why.

Family Factors

Genetic studies find that psychosocial factors in the family account for only a small amount of the variance (less than 15%) in ADHD symptoms (Barkley, 1998), and explanations of ADHD based exclusively on negative family influences have received little support (Silverman & Ragusa, 1992; Willis & Lovaas, 1977). Nevertheless, family influences are important in understanding ADHD for several reasons (Johnston & Mash, 2001; Whalen & Henker, 1999). First, family influences may lead to ADHD symptoms or to a greater severity of symptoms. In some circumstances,ADHD symptoms may be the result of interfering and insensitive early caregiving practices (Jacobvitz & Sroufe, 1987). In addition, for children at risk for ADHD, family conflict may raise the severity of their hyperactive-impulsive symptoms to a clinical level (Barkley, 1996). Second, family problems may result from interacting with a child who is impulsive and difficult to manage (Mash & Johnston, 1990). The clearest support for this child-to-parent direction of effect comes from double-blind placebo control drug studies in which children’s ADHD symptoms were decreased using stimulant medications. Decreases in children’s ADHD symptoms produced a corresponding reduction in the negative and controlling behaviors that parents had previously displayed when their children were unmedicated (Barkley, 1988; Humphries, Kinsbourne, & Swanson, 1978). Third, family conflict is probably related to the presence, maintenance, and later emergence of associated ODD and CD symptoms. Many interventions for ADHD try to change patterns of family interaction to head off an escalating cycle of oppositional behavior and conflict (Sonuga-Barke, Daley, Thompson, LaverBradbury, & Weeks, 2001). Family influences may play a major role in determining the outcome of ADHD and associated problems even if such influences are not the primary cause of ADHD (Johnston & Mash, 2001).

Summary and Integration

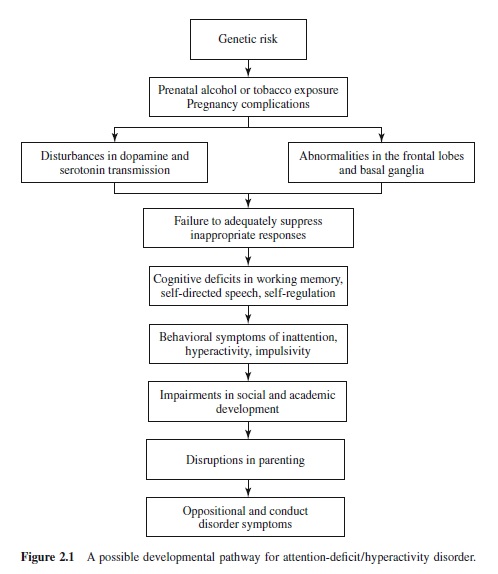

ADHD has a strong biological basis, and for many children, it is an inherited condition. However, the specific cause of the disorder is not known.ADHD is probably the result of a complex pattern of interacting influences.We are just beginning to understand the complex causal pathways through which biological risk factors, family relationships, and broader system influences interact to shape the development and outcome of ADHD over time (Hinshaw, 1994; Taylor, 1999). Although data do not yet permit a comprehensive causal model, a possible developmental pathway for ADHD that highlights several known causal influences and outcomes is shown in Figure 2.1. Findings generally suggest that inherited variants of genes related to the transmission of dopamine and serotonin lead to structural and functional abnormalities in the frontal lobes and basal ganglia regions of the brain. Altered neurological function causes changes in psychological function involving a failure of children to adequately suppress inappropriate responses; this in turnleads to many failures in cognitive performance. The outcome involves a pattern of restless and disorganized behavior that is identified as ADHD, that also impairs social development and functioning, and that may lead to symptoms of ODD and CD (Barkley, 1997; Taylor, 1999).

Internalizing Disorders: Anxiety Disorders

Internalizing disorders involve a core disturbance in emotions and moods such as worry, fear, sorrow, and guilt (ZahnWaxler et al., 2000). The two major types of internalizing disorders are (a) mood disorders and (b) anxiety disorders. Children with mood disorders experience extreme, persistent, or poorly regulated emotional states such as excessive unhappiness or wide swings in mood from sadness to elation. The two most common mood disorders in childhood are major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymic disorder (DD; APA, 2000). MDD and DD are related; many children with DD eventually develop MDD, and some children may experience both disorders (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, & Hops, 1991). A third mood disorder, bipolar disorder, is rare in children, although there is growing interest in this problem in young people (Carlson, Bromet, & Sievers, 2000; Geller & Luby, 1997). In the sections to follow, we limit our discussion to anxiety disorders, highlighting many of the same features that we covered for ADHD. Once again, issues that we raise in discussing anxiety disorders have relevance for other childhood disorders as well.

Anxiety disorders are among most common mental health problems in young people (Majcher & Pollack, 1996; Vasey & Ollendick, 2000). However, because milder forms of anxiety are a common occurrence in normal development and because anxiety disorders are not nearly as damaging to other people or property as are ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders, anxiety disorders frequently go unnoticed, undiagnosed, and untreated (Albano, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1996). Anxiety was once thought of as a transient problem, but we now know that many children who experience anxiety continue to have problems well into adolescence and adulthood (Ollendick & King, 1994). Although isolated symptoms of fear and anxiety are usually short-lived, anxiety disorders in children have a more chronic course (March, 1995). In fact, nearly half of those affected have an illness duration of 8 years or more (Keller et al., 1992).

Symptoms and Types

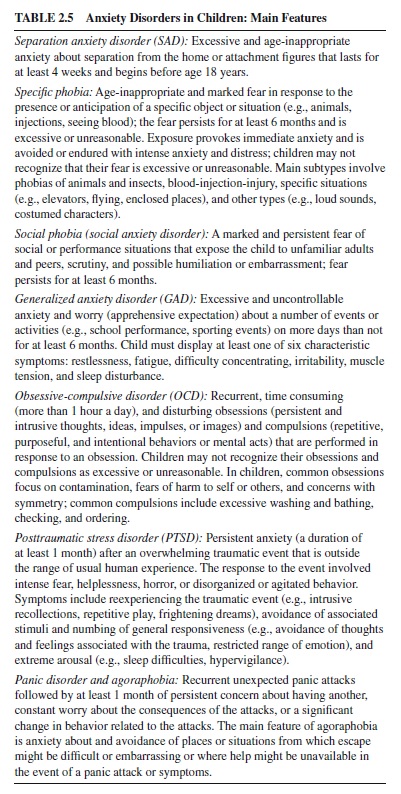

Anxiety is a mood state characterized by strong negative emotion and bodily symptoms of tension in which an individual apprehensively anticipates future danger or misfortune (Barlow, 1988). The term anxiety disorder describes children who experience excessive and debilitating anxiety. However, as described in Table 2.5, these disorders take a number of different forms that vary in focus and severity as a function of development. It is important to keep in mind that there is substantial overlap among these disorders in childhood (Pine, Cohen, Cohen, & Brook, 2000). Many children suffer from more than one type—either at the same time or at different times during their development (Zahn-Waxler et al., 2000).

Epidemiology and Accompanying Disorders

The overall prevalence rates for anxiety disorders in children range from about 6–18% (Costello & Angold, 2000). Rates vary as a function of whether functional impairment is part of the diagnostic criteria, with the informant, and with the type of anxiety disorder.

Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

SAD is the most common anxiety disorder in youths, occurring in about 10% of all children. It seems to be equally common in boys and girls, although when gender differences are found they tend to favor girls (Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1992). Most children with SAD have another anxiety disorder—most commonly generalized anxiety disorder (Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1996). About one third develop a depressive disorder within several months of the onset of SAD. They may also display specific fears of getting lost or of the dark. School reluctance or refusal is also quite common in older children with SAD (King & Bernstein, 2001).

Specific Phobia

About 2–4% or more of all children experience specific phobias at some time in their lives (Essau, Conradt, & Petermann, 2000; Muris & Merckelbach, 2000). However, only a very small number of these children are referred for treatment, suggesting that most parents do not view specific phobias as a significant problem. Specific phobias— particularly blood phobia—are generally more common in girls than boys (Essau et al., 2000). The most common cooccurring disorder for children with a specific phobia is another anxiety disorder. Although comorbidity is frequent for children with specific phobias, it tends to be lower than it is for other anxiety disorders (Strauss & Last, 1993). Phobias involving animals, darkness, insects, blood, and injury typically have their onset at 7–9 years, which is similar to normal development. However, clinical phobias are much more likely to persist over time than are normal fears, even though both decline with age. Specific phobias can occur at any age but seem to peak between ages 10 and 13 years (Strauss & Last, 1993).

Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder)

Social phobia occurs in 1–3% of children, affecting slightly more girls than boys (Essau, Conradt, & Petermann, 1999). Girls may experience more social anxiety because they are more concerned with social competence than are boys and attach greater importance to interpersonal relationships (Inderbitzen-Nolan & Walters, 2000). Among children referred for treatment for anxiety disorders, as many as 20% have social phobia as their primary diagnosis, and it is also the most common secondary diagnosis for children referred for other anxiety disorders (Albano et al., 1996). Even so, many cases of social phobia are overlooked because shyness is common in our society and because these children are not likely to call attention to their problem even when they are severely distressed (Essau et al., 1999). Two thirds of children and adolescents with a social phobia have another anxiety disorder—most commonly a specific phobia or panic disorder (Beidel, Turner, & Morris, 1999). About 20% of adolescents with a social phobia also suffer from major depression. They may also use alcohol and other drugs as a form of self-medication and as a way of reducing their anxiety in social situations (Albano et al., 1996).

Social phobias generally develop after puberty, with the most common age of onset in early to midadolescence (Strauss & Last, 1993). The disorder is extremely rare in children under the age of 10. The prevalence of social phobia appears to increase with age, although little information is available to describe the natural course of the disorder or its long-term outcome.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Along with SAD, GAD is one of the most common anxiety disorders of childhood, occurring in 3–6% of all children (Albano et al., 1996). It is equally common in boys and girls, with perhaps a slightly higher prevalence in older adolescent females (Strauss, Lease, Last, & Francis, 1988). Children with GAD present with a high rate of other anxiety disorders and depression. For younger children, co-occurring SAD and ADHD are most frequent; older children with GAD tend to have specific phobias and major depression, impaired social adjustment, low self-esteem, and an increased risk for suicide (Keller et al., 1992; Strauss, Last, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1988). About half of children referred for treatment for anxiety disorders have GAD. This proportion is higher than it is for adults, in whom the disorder is more common, but fewer adults seek treatment (Albano et al., 1996).

The average age of onset for GAD is 10–14 years (Albano et al., 1996). In a community sample of adolescents with GAD, the likelihood of their having GAD at follow-up was higher if symptoms at the time of initial assessment were severe (Cohen, Cohen, & Brook, 1993). Nearly half of severe cases were rediagnosed after 2 years, suggesting that severe generalized anxiety symptoms persist over time, even in youngsters who have not been referred for treatment.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

The prevalence of OCD in children and adolescents is 2–3%, which suggests that it occurs about as often in young people as in adults (Piacentini & Graae, 1997). Clinic-based studies of younger children indicate that OCD is twice as common in boys as it is in girls. However, this gender difference has not been found in community samples of adolescents, which may be a function of age, referral bias, or both (Albano et al., 1996). The most common comorbidities for OCD are other anxiety disorders, depressive disorders (especially in older children with OCD), and disruptive behavior disorders (Piacentini & Graae, 1997). Substance use disorders, learning disorders, and eating disorders are also overrepresented in children with OCD, as are vocal and motor tics (Peterson, Pine, Cohen, & Brook, 2001; Piacentini & Graae, 1997).

The mean age of onset of OCD is 9–12 years with two peaks—one in early childhood and another in early adolescence (Hanna, 1995). Children with an early onset of OCD (age 6–10) are more likely to have a family history of OCD than are those with a later onset, which indicates a greater role of genetic influences in such cases (Swedo, Rapoport, Leonard, Lenane, & Cheslow, 1989). These children have prominent motor patterns, engaging in compulsions without obsessions and displaying odd behaviors, such as finger licking or compulsively walking in geometric designs. One half to two thirds of children with OCD continue to meet the criteria for the disorder 2–14 years later. Although most children, including those treated with medication, show some improvement in symptoms,fewerthan10%showcompleteremission(Albano, Knox, & Barlow, 1995).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is common in children exposed to traumatic events (Perrin, Smith, & Yule, 2000). The prevalence of PTSD symptoms is greater in children who are exposed to lifethreatening events than it is in those who are not. For example, nearly 40% of children exposed to the Buffalo Creek dam collapse in 1972 showed probable PTSD symptoms 2 years after the disaster (Fletcher, 1996). PTSD in children is also strongly correlated with degree of exposure. In children exposed to a school yard sniper attack, proximity to the attack was linearly related to the risk of developing PTSD symptoms (Pynoos et al., 1987).Traumatized children frequently exhibit symptoms of other disorders besides PTSD, and children with other disorders may have PTSD as a comorbid diagnosis (Famularo, Fenton, Kinscherff, & Augustyn, 1996). The PTSD that occurs in children traumatized by fires, hurricanes, or chronic maltreatment may worsen or lead to disruptive behavior disorders (Amaya-Jackson & March, 1995).

Because PTSD can strike at any time during childhood, its course depends on the age of the child when the trauma occurred and on the nature of the trauma. Because the traumatic experience is filtered cognitively and emotionally before it can be appraised as an extreme threat, how trauma is experienced depends on the child’s developmental level. Some children appear to have different trauma thresholds, although exposure to horrific events is traumatic to nearly all children. Several trauma-related, child, and family factors appear to be important in predicting children’s course of recovery from PTSD following exposure to a natural disaster (La Greca, Silverman, & Wasserstein, 1998). Among these are loss and disruption following the trauma, preexisting child characteristics (e.g., psychopathology), coping styles, and social support (Perrin et al., 2000).

Longitudinal findings suggest that PTSD can become a chronic psychiatric disorder, persisting for decades or a lifetime (Fletcher, 1996). Children with chronic PTSD may display a developmental course marked by remissions and relapses. Moreover, individuals exposed to a traumatic event may not exhibit symptoms until months or years afterwards, when a situation that resembles the original trauma triggers the onset of PTSD. For example, sexual abuse during childhood may lead to PTSD in adult survivors.

Panic Disorder (PD)

Whereas panic attacks are common among adolescents (about 35–65%), panic disorder is much less common, affecting less than 1% to almost 5% of teens (Ollendick, Mattis, & King, 1994). Adolescent females are more likely to experience panic attacks than are adolescent males, and a fairly consistent association has been found between panic attacks and stressful life events (King, Ollendick, & Mattis, 1994; Last & Strauss, 1989). About half of adolescents with PD have no other disorder, and for the remainder an additional anxiety disorder and depression are the most common secondary diagnoses (Kearney, Albano, Eisen, Allan, & Barlow, 1997; Last & Strauss, 1989). After months or years of unrelenting panic attacks and the restricted lifestyle that results from avoidance behavior, adolescents and young adults with PD may develop severe depression and may be at risk for suicidal behavior. Others may begin to use alcohol or drugs as a way of alleviating their anxiety.

The average age of onset for a first panic attack in adolescents with PD is 15–19 years, and 95% of adolescents with the disorder are postpubertal (Bernstein, Borchardt, & Perwien, 1996; Kearney & Allan, 1995). PD occurs in otherwise emotionally healthy youngsters about half the time. The most frequent prior disturbance when there is one is a depressive disorder (Last & Strauss, 1989). Unfortunately, children and adolescents with PD have the lowest rate of remission for any of the anxiety disorders (Last et al., 1996).

Gender, Ethnicity, and Culture

Studies have found a preponderance of anxiety disorders in girls during childhood and adolescence (Lewinsohn, Gotlib, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Allen, 1998). By age 6, twice as many girls as boys have experienced symptoms of anxiety, and this discrepancy persists through childhood and adolescence. Such findings should be interpreted cautiously, however, because the possibility that girls are more likely than are boys to report anxiety cannot be ruled out as an alternative explanation.

Research into the relationship between ethnic and cultural factors and childhood anxiety disorders is limited and inconclusive. Studies comparing the number and nature of fears in African American and White youngsters have found the two groups to be quite similar (Ginsburg & Silverman, 1996; Treadwell, Flannery-Schroeder, & Kendall, 1994). However, African American children report more symptoms of anxiety than do White children (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Henderson, & Harwell, 1998). White children endorse more symptoms of social phobia and fewer symptoms of separation anxiety than do African American children (Compton, Nelson, & March, 2000). The underrepresentation of minorities and children of lower socioeconomic status (SES) for certain anxiety disorders such as OCD could also reflect a bias in which minority children are less likely to be referred for treatment (Neal & Turner, 1991).

Among children referred for anxiety disorders, Whites are more likely to present with school refusal and higher severity ratings, whereas African Americans are more likely to have a history of PTSD and a somewhat greater number of fears (Last & Perrin, 1993). Although anxiety may be similar in the two groups, patterns of referral, help-seeking behaviors, diagnoses, and treatment processes are likely to differ. For example, African Americans may be more likely to turn for help with their child’s OCD symptoms to members of their informal social network, such as clergy or medical personnel, than to mental health professionals (Hatch, Friedman, & Paradis, 1996). Their family members are also less likely to be drawn into the child’s OCD symptoms.

Research comparing phobic and anxiety disorders in Hispanic and White children finds marked similarities on most measures, including age at intake, gender, primary diagnoses, proportion of school refusal, and proportion with more than one diagnosis. Hispanic children are more likely to have a primary diagnosis of SAD. Hispanic parents also rate their children as more fearful than do White parents (Ginsburg & Silverman, 1996). Few studies have examined anxiety disorders in Native American children. Prevalence estimates from one study of Native American youth in Appalachia (mostly Cherokee) indicate rates of anxiety disorders similar to those for White youth, with the most common disorder for both groups being SAD. Rates of SAD were slightly higher for Native American youth, especially for girls (Costello, Farmer, Angold, Burns, & Erkanli, 1997).

Although cross-cultural research into anxiety disorders in children is limited, specific fears in children have been studied and documented in virtually every culture. Developmental fears (e.g., a fear of loud noises or separation anxiety) occur in children of all cultures at about the same age. The number of fears in children tends to be highly similar across cultures, as does the presence of gender differences in pattern and content. Nevertheless, the expression and developmental course of fear and anxiety may be affected by culture. Cultures that favor inhibition, compliance, and obedience have increased levels of fear in children (Ollendick, Yang, King, Dong, & Akande, 1996).

Accompanying Disorders and Symptoms

A child’s risk for accompanying disorders varies with the type of anxiety disorder. Social phobia, GAD, and SAD are more commonly associated with depression than is specific phobia. Depression is also diagnosed more often in children with multiple anxiety disorders and in those who show severe impairments in their everyday functioning (Bernstein, 1991).

The strong and undeniable relationship between anxiety and depression in young people merits further discussion (Kendall & Brady, 1995; Mesman & Koot, 2000). Does anxietyleadtodepression,areanxietyanddepressionthesamedisorder with different clinical features, are they on a continuum of severity, or are they distinct disorders with different causes but some overlapping features (Seligman & Ollendick, 1998; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2000)? Children with anxiety and depression are older at age of presentation than are children with anxiety alone, and in most cases symptoms of anxiety both precede and predict those of depression (Brady & Kendall, 1992; Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998). Symptoms of anxiety and depression may form a single indistinguishable dimension in younger children but are increasingly distinct in older children and in children with at least one diagnosable disorder (Cole, Truglio, & Peeke, 1997; Gurley, Cohen, Pine, & Brook, 1996). Recent studies of children’s negative emotional symptoms generally support the three distinct constructs of anxiety, depression, and fear, with anxiety corresponding to negative affect, depression to low positive affect, and fear to physiological overarousal (Chorpita, Daleiden, Moffitt,Yim, & Umemoto, 2000; Joiner & Lonigan, 2000; Lonigan, Hooe, David, & Kistner, 1999).

Associated Features

Children with anxiety disorders are typically of normal intelligence, and there is little evidence of a strong relationship between anxiety and IQ. However, excessive anxiety may be related to deficits in specific areas of cognitive functioning, such as memory, attention, and speech or language. High levels of anxiety can interfere with academic performance. One study found that anxiety in the first grade predicted anxiety in the fifth grade and significantly influenced fifthgrade achievement (Ialongo, Edelsohn, Werthamer-Larsson, Crockett, & Kellam, 1995). The specific mechanisms involved could include anything from frequent absences to direct interference on cognitive tasks, such as writing a test or solving a math problem.

Children with anxiety disorders selectively attend to information that may be potentially threatening, a tendency referred to as anxious vigilance or hypervigilance (Vasey, El-Hag, & Daleiden, 1996). Anxious vigilance is maintained because it permits the child to avoid potentially threatening events by means of early detection and with minimal anxiety and effort. Although this strategy may benefit the child in the short term, it has the negative long-term effect of maintaining and heightening anxiety by interfering with the informationprocessing and coping responses needed to learn that many potentially threatening events are not so dangerous after all (Vasey et al., 1996).

When faced with a clear threat, both normal and anxious children use rules to confirm information about danger and play down information about safety. However, high-anxious children often do this in the face of less obvious threats, suggesting that their perceptions of threat activate a dangerconfirming reasoning strategy (Muris, Merckelbach, & Damsma, 2000). Anxious children generally engage in more negative self-talk than do nonanxious children. However, positive self-talk does not distinguish anxious children from controls, suggesting that their internal dialogue is more negative but not necessarily less positive than that of other children (Treadwell & Kendall, 1996). Although cognitive errors and distortions are associated with anxiety in children, their possible role in causing anxiety has not been established (Seligman & Ollendick, 1998).

Children with anxiety disorders often experience somatic symptoms such as stomachaches or headaches. These complaints are more common in youngsters with PD and SAD than in those with a specific phobia. Somatic complaints are also more frequent in adolescents than in younger children and in children who display school refusal. Children with anxiety disorders may also have sleep disturbances. Some may experience nocturnal panic—an abrupt waking in a state of extreme anxiety—that is similar to a daytime panic attack. Nocturnal panic attacks usually occur in adolescents with PD (Craske & Rowe, 1997).

Many children with anxiety disorders have low social competence and high social anxiety, and their parents and teachers are likely to view such children as anxious and socially maladjusted (Chansky & Kendall, 1997; Krain & Kendall, 2000; Strauss, Lease, Kazdin, Dulcan, & Last, 1989). Compared to their peers, these children are more likely to see themselves as shy and socially withdrawn and more likely to report low selfesteem, loneliness, and difficulties in starting and maintaining friendships. Some of their difficulties with peers may be related to specific deficits in emotion understanding—particularly in hiding and changing emotions (Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000). Findings are mixed regarding how children with anxiety disorders are viewed by other children (Kendall, Panichelli-Mindel, Sugarman, & Callahan, 1997). It appears that childhood anxiety disorders are most likely to be associated with diminished peer popularity when they coexist with depression (Strauss, Lahey, Frick, Frame, & Hynd, 1988).

Causes

It is important to recognize that different anxiety disorders may require different causal models. For example, the affective, physiological, and interpersonal processes in GAD may differ from those in other anxiety disorders (T. M. Borkovec & Inz, 1990). Current models of anxiety emphasize the importance of interacting biological and environmental influences (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2000).

Early Temperament

Early temperament has been implicated as a precursor for anxiety disorders. Children differ markedly in their reactions to novel or unexpected events—perhaps because of genetics, gender, cultural background, prior experience, or a combination of factors. Orienting, attending, vigilance, wariness, and motor readiness in response to the unfamiliar are important mechanisms for survival. From an evolutionary perspective, abnormal fears and anxieties partly reflect variation among infants in their initial behavioral reactions to novelty (Kagan, 1997).

This variation is a reflection of inherited differences in the neurochemistry of structures that are thought to play an important role in detecting discrepant events (Kagan, Snidman, Arcus, & Reznick, 1994). These structures include the amygdala and its projections to the motor system, the cingulate and frontal cortex, the hypothalamus, and the sympathetic nervous system. Children who have a high threshold to novelty are presumed to be at low risk for developing anxiety disorders. Other children are born with a tendency to become overexcited and to withdraw in response to novel stimulation—an enduring trait for some and a possible risk factor for the development of later anxiety disorders (Kagan & Snidman, 1999; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999).

The pathway from a shy-inhibited temperament in infancy and childhood to a later anxiety disorder is neither direct nor straightforward. Although a shy-inhibited temperament may contribute to later anxiety disorders, it is not an inevitable outcome (Prior, Smart, Sanson, & Oberklaid, 2000). Such an outcome probably depends on whether the inhibited child grows up in an environment that fosters this tendency (Kagan, Snidman, & Arcus, 1992). For example, a parent’s use of firm limits that teach inhibited children how to cope with stress may reduce their risk for later anxiety. In contrast, it is possible that well-meaning but overprotective parents who shield their sensitive child from stressful events may inadvertently encourage a continuation of timidity by preventing the child from confronting fears and—by doing so— eliminating them. Such tendencies in the parents of inhibited children may be common (Hirshfeld et al., 1992; Rosenbaum et al., 1991). Thus, inhibited children may be at high risk not only because of their inborn temperament but also because of their elevated risk of exposure to anxious, overprotective parenting (Turner, Beidel, & Wolff, 1996).

Genetics

Family and twin studies suggest a biological vulnerability to anxiety disorders, indicating that children’s general tendencies to be inhibited, tense, or fearful are inherited (DiLalla, Kagan, & Reznick, 1994). However, little research exists at present to support a direct link between specific genetic markers and specific types of anxiety disorders. Contributions from multiple genes seem related to anxiety only when certain psychological and social factors are also present.

The overall concordance rates for anxiety disorders are significantly higher for monozygotic (MZ) twins than for dizygotic (DZ) twins (Andrews, Stewart, Allen, & Henderson, 1990). However, MZ twin pairs do not typically have the same types of anxiety disorders. This finding suggests that what is inherited is a disposition to become anxious, and the form that the disorder takes is a function of environmental influences. Twin and adoption studies of anxiety in children and adolescents may be summarized as follows: There is a genetic influence on anxiety in childhood that accounts for about one third of the variance in most cases; heritability for anxiety may be greater for girls than for boys; shared environmental influences or experiences that make children in the same family resemble one another (e.g., maternal psychopathology, ineffective parenting, or poverty) have a significant influence on anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (Eley, 1999).

Two lines of evidence suggest that anxiety disorders run in families. First, parents of children with anxiety disorders have increased rates of current and past anxiety disorders. Second, children of parents with anxiety disorders have an increased risk for anxiety disorders (McClure, Brennan, Hammen, & Le Brocque, 2001). Children of parents with anxiety disorders are about five times more likely to have anxiety disorders than are children of parents without anxiety disorders (Beidel & Turner, 1997). However, they are not necessarily the same anxiety disorders (Mancini, van Ameringen, Szatmari, Fugere, & Boyle, 1996). Nearly 70% of children of parents with agoraphobia meet diagnostic criteria for disorders such as anxiety and depression, and they report more fear and anxiety and less control over various risks than do children of comparison parents. However, the fears of parents with agoraphobia and the fears of their children are no more closely aligned than are those of nonanxious parents and their children, once again supporting the view that it is a general predisposition for anxiety that is perpetuated in families (Capps, Sigman, Sena, & Henker, 1996).

Neurobiological Factors

The part of the brain most often connected with anxiety is the limbic system, which acts as a mediator between the brain stem and the cortex (Sallee & Greenawald, 1995). Signs of potential danger are monitored and sensed by the more primitive brain stem, which then relays them to the higher cortical centers via the limbic system. This brain system is referred to as the behavioral inhibition system and is believed to be overactive in children with anxiety disorders. Neuroimaging studies point to abnormalities in limbic-based amygdala, septohippocampal, and brain stem hypothalamic circuits as being associated with anxiety disorders (Pine & Grun, 1999).

Agroup of neurons known as the locus ceruleus is a major brain source for norepinephrine, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Overactivation of this region is presumed to lead to a fear response, and underactivity is presumed to lead to inattention, impulsivity, and risk taking. Abnormalities of these systems appear to be related to anxiety states in children (Sallee & Greenawald, 1995). The neurotransmitter system that has been implicated most often in anxiety disorders is the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) system.

Family Factors

Surprisingly little is known about the relation between parenting styles or family factors and anxiety disorders. Parents of anxious children are often described as overinvolved, intrusive, or limiting of their child’s independence. Observations of interactions between 9- to 12-year-old children with anxiety disorders and their parents found that parents of children with anxiety disorders were rated as granting less autonomy to their children than were other parents; the children rated their mothers and fathers as being less accepting (Siqueland, Kendall, Steinberg, 1996). Other studies have found that mothers of children previously identified as behaviorally inhibited are more likely to use criticism when interacting with their children and that emotional overinvolvement by parents is associated with an increased occurrence of SAD in their children (Hirshfeld, Biederman, Brody, & Faraone, 1997; Hirshfeld, Biederman, & Rosenbaum, 1997). These findings generally support the notion of excessive parental control as a parenting style associated with anxiety disorders in children, although the causal role of such a style is not yet known (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Rapee, 1997).

Not only do parents of children with anxiety disorders seem to be more controlling than do other parents, but they also have different expectations of their children. For example, when they thought the child was being asked to give a videotaped speech, mothers of children with anxiety disorders expected their children to become upset and had low expectations for their children’s coping (Kortlander, Kendall, & Panichelli-Mindel, 1997). It is likely that parental attitudes shape—and are shaped by—interactions with the child, during which parent and child revise their expectations and behavior as a result of feedback from the other (Barrett, Rapee, Dadds, & Ryan, 1996).

Insecure early attachments may be a risk factor for the development of later anxiety disorders (Bernstein et al., 1996; Manassis & Bradley, 1994). Mothers with anxiety disorders have been found to have insecure attachments themselves, and 80% of their children are also insecurely attached (Manassis, Bradley, Goldberg, Hood, & Swinson, 1994). Infants who are ambivalently attached have more anxiety diagnoses in childhood and adolescence (Bernstein et al., 1996).Although it is a risk factor, insecure attachment may be a nonspecific one in that many infants with insecure attachments develop disorders other than anxiety (e.g., disruptive behavior disorder), and many do not develop any disorders.

Summary and Integration

There is much debate regarding the distinctness of the DSMIV-TR childhood anxiety disorders, with some individuals emphasizing the similarities among these disorders and others emphasizing the differences (Pine, 1997). An emphasis on similarities is consistent with the strong associations among the different disorders, the presence of shared risk factors such as female gender, and evidence of a broad genetic predisposition for anxiety. An emphasis on differences is consistent with different developmental progressions and outcomes as well as differences in the biological correlates of anxiety disorders in children versus adults (Pine et al., 2000). Children with anxiety disorders will most likely display features that are shared across the various disorders as well as other features that are unique to their particular disorder.

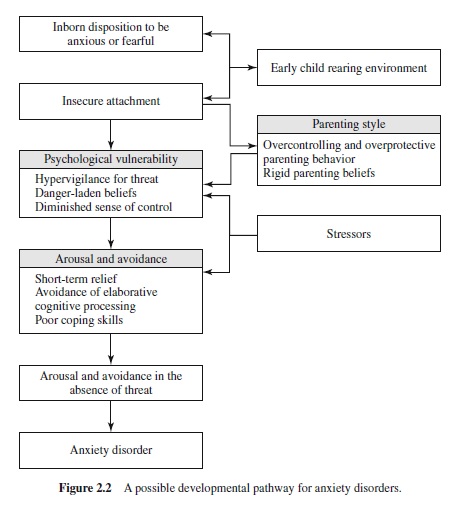

A possible developmental pathway for anxiety disorders in children is shown in Figure 2.2. In children with an inborn predisposition to be anxious or fearful, the child’s sense that the world is not a safe place may create a psychological vulnerability to anxiety. After anxiety occurs, it feeds on itself. The anxiety and avoidance continue long after the stresses that provoked them are gone. In closing, it is important to keep in mind that many children with anxiety disorders do not continue to experience problems as adults. Therefore, it will be important to identify risk and protective factors that would explain these differences in outcomes (Pine & Grun, 1999).

Current Issues and Future Directions

ADHD and anxiety—like most disorders of childhood and adolescence—involve broad patterns of behavior and dysfunction that unfold over time as the result of multiple interacting risk and protective factors in the child and the environment (Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). Building on our discussion of these disorders, we next highlight a number of current issues and future directions related to the study of child psychopathology more generally.

Defining Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence