Sample Education and Credentialing in Clinical Psychology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

This research paper is designed to familiarize readers with the broad realm of education, training, licensing, and credentialing in professional psychology across the North American continent. Particular attention is paid to the development and implementation of these components in both the United States and Canada because of their similar developmental histories and strong cross-border interchanges and influences.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Clearly, the description of education, training, and credentialing of clinical psychology is not brief. We describe each component from the perspective of the major organizations in the United States and Canada, and to some degree in Mexico, that participate in the structures established to educate, train, accredit, identify, and certify programs and individuals. We examine some influences from external forces that have shaped these developments. We cover what would be important from the perspective of an individual student or professional looking for a single source.

Clinical Versus Clinical Psychology: The Evolution of Definitions in the United States and Canada

The U.S. Experience

Psychology’s history of attempts to differentiate types of psychologists have been either resisted or encouraged, often depending on what organization or constituent group was likely to benefit. Defining the profession broadly in state licensing laws and regulations made sense in terms of enhancing the overall political and professional power of psychology. The scope of practice and the group of psychologists licensed influenced decisions about diagnosis, assessment, and reimbursement and also provided the profession with prestige needed to compete with more senior professions. The American Psychological Association (APA) acted quickly 45 years ago to define entry to the profession as a person with a doctoral degree (APA Committee on Legislation, 1955). Then, for a licensed psychologist to be seen as distinctive, a specialty label was chosen, typically based on the name of the program completed. Today, debating the differences between clinical psychology and counseling psychology, as only one example, divides the profession at times and occupies incredible energy that might be better spent elsewhere.

After many battles and no winners, the fervor that once attached itself to being a clinical psychologist has moved to a different position that appears somewhat accepted, namely that professional psychology is made up of many types of psychologists, typically identified initially by the title of the doctoral program (and thus affected by the training philosophy in that area), but all being trained at ameliorating some type of dysfunction or discomfort in humans or organizations. As a result, the word clinical embraces a wider array of psychologists, helps focus on their commonalities, and positions psychology to speak with something closer to one voice (Belar & Perry, 1992).

It has taken us 55 years to reach some degree of comfort with that perspective, and although it is not universal, it is the approach that we bring to this review of education, training, licensing, and credentialing in North America. Although we later introduce some history of the development of professional psychology and attendant national conferences for perspective, we do not limit ourselves to describing the developmental status and future of clinical psychology only. Instead, we include “clinical psychology” or “professional psychology” as identifiers of the broad set of applied psychologists who carry on a vast array of professional activities. (The histories of several branches of applied psychology are elaborated in vol. 1 of this Handbook.)

Recently, APA has acted on petitions from different areas of psychology practice to determine whether (a) the area should be approved officially as a “specialty” in professional psychology (e.g., clinical neuropsychology), (b) the area should be clearly labeled with “clinical” as a prefix (e.g., clinical health), (c) the area should be officially approved as a specialty based on a de jure review instead of the de facto approval that occurred at various stages throughout the development of the profession (e.g., clinical, counseling, and school psychology), or (d) the area qualifies for a proficiency but not a specialty (e.g., clinical child).

What are the current and official U.S. definitions? Following we excerpt part of the definitions approved by APA at the time that these three de facto specialties were officially continued as specialties:

Clinical psychologists assess, diagnose, predict, prevent, and treat psychopathology, mental disorders and other individual or group problems to improve behavior adjustment, adaptation, personal effectiveness and satisfaction.

Counseling psychologists help people with physical, emotional, and mental disorders improve well-being, alleviate distress and maladjustment, and resolve crises.

School psychologists . . . provide a range of psychological diagnosis, assessment, intervention, prevention, health promotion, and program development and evaluation services.

These definitions can be accessed in full from the following websites: www.apa.org/crsppp/clinpsych.html, www.apa.org/ crsppp/counseling.html and www.apa.org/crsppp/schpsych .html.

A more inclusive definition of practice was provided by the National Register of Health Service Providers in Psychology (hereafter National Register) when it defined without reference to specialty title the health service provider in psychology. This 1974 definition has been incorporated into the statute or regulations by nine state licensing boards to identify the health service providers among all those licensed and approved by APA (APA Council of Representatives, 1996) and the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB, 1998):

A “Health Service Provider in Psychology” is “a psychologist currently and actively licensed/certified/registered at the independent practice level in a jurisdiction, who is trained and experienced in the delivery of direct, preventive, assessment and therapeutic intervention services to individuals whose growth, adjustment, or functioning is impaired or to individuals who otherwise seek services.” (Council for the National Register of Health Service Providers in Psychology, 2000, p. 11)

The necessity to be as inclusive as possible is highlighted by U.S. federal legislation for purposes of Medicare reimbursement. A clinical psychologist was originally defined as someone who graduated from a clinical psychology program. Although this narrower legal definition would have applied to the majority of graduates of professional psychology programs, it would have eliminated many qualified health service psychologists from providing needed services to Medicare patients. Responding to public comments, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) now defines clinical psychologists as persons who hold doctoral degrees in psychology and are state licensed at the independent practice level of psychology to furnish diagnostic, assessment, preventive, and therapeutic services. Those psychologists who do not meet those requirements are limited to providing diagnostic testing services for Medicare reimbursement (Federal Register, 1998).

The Canadian Experience

Much as in the United States, the term clinical has created taxonomic confusions in Canadian psychology that had to be addressed. The collective remedy to date in Canada is to endorse the term professional psychology to denote the larger set of more direct service and applied branches of psychology. As an example of this issue, Dobson and Dobson (1993) noted that “there remains a tendency to equate professional psychology with clinical psychology. However, the following amply demonstrate the falsity underlying this statement—professional psychology in Canada exists in a diverse range of work settings, practice areas and work activities” (p. 5). Likewise, Goodman (2000) stated that “clinical psychology is not synonymous with professional psychology. It is a subset along with school psychology, counseling psychology, forensic-correctional psychology, neuropsychology, rehabilitation psychology, and industrial organizational psychology. While there is overlap among the subsets, each has its own unique features” (p. 25).

Canadian clinical psychology (historically read “applied psychology, ”now “professional psychology”)—much like U.S. clinical psychology—represents a story of ongoingbroad-based development rooted in historic circumstances, emerging societal and professional needs, and somewhat unique Canadian academic and practice traditions. Likewise, clinical psychology as a formalized branch or subset of the larger Canadian professional psychology arena also draws its own identity in Canada from many of the larger formative forces impacting Canadian professional psychology.

Given the somewhat parallel problems in both the United States and Canada with the term clinical, we propose to use the term professional psychologist for those psychologists in both countries who provide health and other similar services aimed at ameliorating and addressing problems presented by individuals or organizations.

Assessing Professional Competence: The Role of Certification Mechanisms in Professional Psychology

The terms credentialing and certification are often used interchangeably. Credentialing typically refers to individuals who have been certified as having met some standard. For instance, the university or professional school certifies to the public that the graduate has met the requirements of the degree by awarding the diploma. Credentialing and certification thus usually refer to an individual achievement. Certification indicates quality, “especially in the absence of knowledge to the contrary” (Drum & Hall, 1993, p. 151). According to Stromberg (1990), “certification is a process by which government or a private association assesses a person, facility, or program and states publicly that it meets specific standards”—these standards are considered to be significant measures. Thus, we will see the term certification again when we discuss licensing of individual psychologists. Accreditation and designation refer to the certification of programs, as opposed to individuals. These three terms, credentialing, accreditation, and designation, are certification mechanisms.

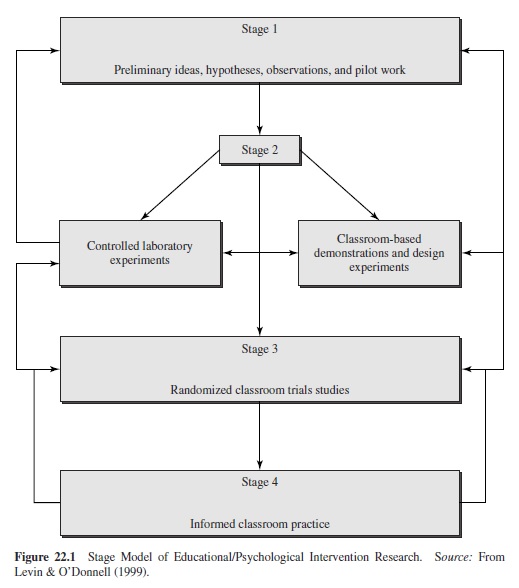

Self-Regulation and Government Regulation of Education and Training Programs

Part of the responsibility of belonging to a profession includes the responsibility to regulate that profession. Regulating a profession includes many activities, one of which is the establishment of education and training standards, followed by the application of those standards to education and training programs. Psychology has at least three major players in its self-regulation of education and training: (a) the professional associations (APA and Canadian Psychological Association, or CPA, Committees on Accreditation), (b) the licensing and credentialing bodies (ASPPB’s National Register Designation Project), and (c) statewide or provincial review or approval of programs, such as in Ontario or New York State (New York State Doctoral Evaluation Project, 1990). Accreditation and designation of training programs, such as internships and postdoctoral residencies, involve the accrediting bodies as well as the Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers (APPIC) programs. Future psychologists are affected by these organizations and the standards they employ as illustrated by the person moving through the education, training, licensing, credentialing, and certification process as illustrated in Figure 20.1. The organizations identified are described by function in Table 20.1.

Armed with an overview of these private and public influences that constitute part of organized psychology, we now consider the various educational levels and models for training of professional psychologists, especially as relating to the competencies expected of psychologists in North America.

Professional Education

Doctoral-Level Education Versus Subdoctoral-Level Education

In both the United States and Canada, doctoral-level education has been seen as the long-desired entry practice level for clinical psychologists. In the United States there has been a general consensus about this educational requirement for the autonomous professional practice of psychology, whereas in Canada there is widespread autonomous practice at both the master’s and the doctoral level of education. Autonomous practice for master’s level psychologists exists only in Vermont, West Virginia, and Kentucky (except for the case of school psychologists practicing in educational settings). Other states do have master’s-level practitioners, but such individuals are typically supervised or restricted in their practice roles (ASPPB, 2001).

These differential degree requirements for autonomous practice in Canada and the United States reflect a number of different national factors. In Canada such entry-level educational criteria reflect a somewhat different level of general availability of doctoral-level training programs in relation to applicant pool combined with a far more restrictive view on private graduate education programs. In Canada there are currently 17 doctoral clinical programs that accommodate approximately 10% of clinical applications (Robinson et al., 1998), whereas there is a much wider availability of both university-based and freestanding doctoral-level clinical training programs and available training slots in the United States. Unlike in the United States, the almost complete absence of freestanding, for-profit, doctoral-level professional psychology training institutions in Canada (i.e., entities outside the publicly funded Canadian university system) has also meant that doctoral-level clinical psychology has been much slower to develop. Finally, unlike in the United States, where there has been rapid development of doctoral-level clinical training and commensurate doctoral-level state licensing requirements, the far slower growth of Canadian clinical training has meant that Canadian jurisdictions and licensing boards have necessarily made far greater use of master’s degree programs as sources for generating autonomous psychologist practitioners—especially in the Atlantic provinces of Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. In addition, Quebec has had a longstanding tradition of master’s-level practitioner programs. In effect, about two thirds of the 12,000 practicing Canadian psychologists are trained at the master’s level (Gauthier, 1997; Robinson et al., 1998). Canada is still grappling with how to provide increased numbers of doctoral-level professional psychology training programs.

In Mexico (and for most of Europe and Latin America), the typical psychologist—whether licensed or not—is trained at the subdoctoral level following an introduction to professional training that begins after two years of high school (bachillerato). The U.S. and Canadian pattern of obtaining a bachelor’s degree prior to entry to graduate training is not typical in many of these countries. In most, obtaining a master’s degree and a doctoral degree is a route chosen only for those intending to teach and do research in a university setting. A comparison of the education, training, and licensure of psychologists in North American is illustrated in Table 20.2.

Sequence and Models of Education

The Scientist-Practitioner Model

In both the United States and Canada the sequence of doctoral-level training for students following the scientist-practitioner model (the Boulder-model PhD) is largely similar, although there are a few notable differences. In the United States students normally begin graduate education with a set of basic core courses prescribed for their first year. In Canada students are normally only admitted to clinical psychology graduate programs based on an undergraduate bachelor of science honors degree in psychology, which affords much of the preparation normally provided in the first year of psychology graduate training in the United States.

Overall, content of training for Canada and the United States is quite similar. Each country requires that doctorallevel clinical training be conducted in the four primary areas of (a) biological bases of behavior, (b) cognitive and affective bases of behavior, (c) social bases of behavior, and (d) individual differences in behavior, as well as statistics, research design, psychological measurement, ethics and standards, and history and systems of psychology. Training in specific skills such as psychodiagnosis, assessment, individual and group intervention, consultation, and program evaluation also constitute part of formal training (APA, 2000; CPA, 1991).

After 3 years of full-time study, including various practicums, graduate students typically undertake a comprehensive examination of their knowledge in the required areas of study. Afterward, work begins on the doctoral thesis. Usually after approval of the dissertation topic (and data collection), students embark on a full-time year of internship training designed to anchor their know ledge, values, and skills in a practice setting relevant to their career goals. The end result of the scientist-practitioner model of training is intended to be a doctoral-level clinical psychologist who is both a producer of research and a high-quality, competent practitioner. The Boulder model of training has been reaffirmed in the United States and Canada on a number of occasions and continues as an important framework for psychologists pursuing more academically oriented careers as well as for psychologist practitioners. The scientist-practitioner PhD is the only model endorsed by Counseling Psychology (Gelso & Fretz, 2001). O’Sullivan and Quevillon (1992) surveyed APAaccredited programs, and with 90 of the programs responding, there was a 98% conformance to the Boulder model.

Maher (1999) recently compared research-oriented to professional-applied PhD programs using National Research Council (NRC) data published in 1995. The professional applied programs (a) were rated lower in quality of faculty, who in turn had a lower average publication record; (b) depended more on a part-time faculty and on assigning more students to each faculty member; (c) admitted students with lower GRE scores; and (d) awarded more PhDs since the 1982 NRC data. Maher concluded that a PhD means something very different when awarded by a professional school that is not seated within a research-oriented institution.

The Practitioner Model

The first practice-oriented doctorate of psychology (PsyD) programs in the late 1950s and 1960s soon led to a rapid growth of PsyD programs by the 1980s (D. R. Peterson, Eaton, Levine, & Snepp, 1982). Based on information collected and compiled by APA Research Office in 2000 on 1998 graduates, about 41% of all clinical graduates in the United States (2,302) were granted PsyD degrees (952), with approximately 58% of PsyDs and PhDs in clinical psychology (1333) awarded by professional schools. The existence of large class size in both university-based and freestanding schools of professional psychology in the United States means that a majority of clinical students are now coming from professional school backgrounds. Therefore, in the United States the practitioner model (PsyD) is a welldeveloped and now quite well-accepted doctoral degree for clinical psychology. Here the emphasis is on developing a strong and knowledgeable practitioner who understands and is a knowledgeable consumer of research but who may not necessarily produce research as part of his or her career path.

Notwithstanding the notable strengths of the scientistpractitioner model of training, the history of the PsyD model in the United States stems from a number of disparities in objectives and dissatisfactions with the first model of training for clinical psychologists. Perhaps the most notable disparity in the Boulder model of training has been the fact that few U.S. PhD clinicians outside of academic settings have devoted time to research and that most have published virtually nothing after having received their PhDs. In general, the PhD model takes an excessive amount of time (6.8 years) to complete relative to the 5.1-year completion time for the PsyD (Gaddy, Charlot-Swilley, Nelson, & Reich, 1995).

In Canada the PsyD is only beginning to come to gestation. The relatively recent and slower evolution of doctoral-level clinical training from a predominantly research-oriented to a more balanced scientist-practitioner orientation is a function both of the exclusively university-based departmental training approach and of the historic desire to embed clinical training in a predominantly research-oriented framework. Nonetheless, similar criticisms about the scientist-practitioner have emerged in Canada. Hunsley and Lefebvre (1990) found that most PhD-trained Canadian professional psychologists neither are significant producers of research nor wish to pursue research as part of their careers. Moreover, much like the United States, most students in Canadian doctoral programs take about seven years to complete their PhDs—in large part because of the growing dual curricula demands to cover both strong research components and an ever expanding professional component (Robinson et al., 1998). Finally, there is very little opportunity in the Canadian scientist-practitioner model to accommodate the estimated 40% of those master’slevel psychologists who might wish to upgrade their training to a doctoral-level standard (Handy & Whitsett, 1993).

Notwithstanding that most of the clinical training programs for master’s degrees in Canada have been quite rigorous precisely because they have often led to autonomous practice, the resultant professional practice mosaic across Canada is now a major focus of concern for Canadian professional psychology. Serious national efforts to arrive at some kind of national mobility mechanism for Canadian professional psychologists are now being driven by Canada’s Agreement on Internal Trade, which aims, among other things, to foster the mobility of professional services across Canada. Among options being considered—beside grandparented mutual recognition agreements for currently practicing psychologists—is a more flexible doctoral training model, that is, a PsyD that might help bridge the training gap across provinces with differential autonomous practice requirements (Hurley, 1998; Robinson et al., 1998).

What will a made-in-Canada scholar-practitioner program look like? Serious work has already begun in Quebec to offer a university-based competency-driven PsyD based on eight core domains of training (Poirier et al., 1999). Drawing on the recommendations of the CPA PsyD Task Force (Robinson et al., 1998) and the work of Poirier et al. (1999) in Quebec, and with Quebec governmental approval, several Quebec universities have now developed PsyD program tracks and curricula that will soon admit students. Offered as a complementary model to the scientist-practitioner PhD, the Quebec PsyD will seek to highlight core practice-oriented competencies that are based in a grounding of scientific knowledge and critical thinking and will be of shorter duration than the typical PhD. Such programs should help students attain the necessary training skills at a doctoral level, which otherwise would have required extended master’s training and supervision.

Other provinces are also either considering or developing PsyD-model training plans. However, noting U.S. outcome research (Yu et al., 1977) on attributes of quality PsyD training programs (e.g., smaller student bodies, low facultystudent ratios, and being university-based rather than freestanding), the CPA PsyD task force’s final report recommendation for similar attributes for Canadian PsyD programs will most likely serve as a defining template across the country. Finally, given the very large financial burden for students often accompanying more profit-driven PsyD programs in some areas of the United States and given the strong Canadian tradition endorsing lower cost publicly funded Canadian universities, the made-in-Canada PsyD programs may well look for a variety of cost-offset mechanisms for moderating the impact of such student debt on early career development.

The training of professional psychologists in Mexico (as well as in Europe and Latin America) is closest to an almost exclusively professional training program. In fact, the practitioner’s degree (licentiate) often comes first and leads immediately to a permanent license (cédula), with a small portion of individuals then deciding to get the necessary research degree or other training needed for employment in an academic setting. This is almost the opposite of what occurs in the United States and Canada, where academic-scientific foundational work precedes professional training.

Professional Training: Practicums, Internship, and Postdoctoral Components

One of the distinguishing features of any profession is handson training. Professionals are expected to be not only knowledgeable about their subject area but also able to perform competently. Professional psychology is no different in this regard from other professions, and the field has spent much collective time and resources in developing coherent, sequential training experiences to integrate the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to become a competent professional. We now examine each of the typical training experiences that psychologists undertake as part of their formal professionalization.

Practicums

Developing Basic Practice Competence

Practicum experience is often the first professional training encounter for professional psychology students. Here, the Oxford American Dictionary’s various definitions of practice all weigh heavily in the equation of practicum training, that is, (a) “action as opposed to theory,” (b) “a habitual action,” (c) “repeated exercise to improve one’s skill,” and (d) “professional work” (Ehrlich, Flexner, Carruth, & Hawkins, 1980, p. 700). Having acquired the fundamental knowledge and basic skills required for beginning the practice of clinical work through various courses, students are now expected to begin putting such knowledge, skills, and ethical values to use in real-life encounters with clients and patients.

As the first formalized training component, the practicum is often both quite challenging and exciting for students. Practicum goals usually include the strengthening of interviewing skills, the basics of translating theory into practice through direct clinical encounters (and through supervision), and the development and refinement of basic assessment, report writing, and consultation skills. Such exercises are normally part of a course requirement and are usually conducted in training clinics, university counseling centers, or in school settings, which often translates into direct involvement with a wide variety of clients and presenting problems.

Although cases are usually selected and assigned to students based on their incoming skill levels, many challenges and surprises often await as clinical work progresses. Here, the clinical student begins to encounter and cultivate “an important characteristic of the clinician—the capacity to tolerate ambiguity” (Phares, 1988, p. 33). Such personal characteristics as interpersonal awareness and sensitivity, basic respect for diversity in human living, and—perhaps most importantly—respect for the dignity of persons —all relate not only to the capacity to tolerate ambiguity but also to the capacity to appreciate a broad range of human behaviors and customs with their attendant avenues of adaptation and growth as well as dysfunction and potential pathology. These characteristics also set the stage for appreciation of the broad range of other strengths as students later advance through their own career steps in the profession.

In summary, practicums are generally sequenced in difficulty and variety in order for students to develop systematically their clinical skills and intervention techniques. Although students in both Canada and the United States are expected to complete at least 600 to 1,000 hours of practicum training prior to admission to the internship, the actual figures reported as part of the application for the internship are much higher than that, as students increasingly feel that they are more marketable for an internship with more and diverse hours. Depending on the internship setting (community mental health centers, medical centers, hospitals, or university counseling centers) and the information on which it is based (an internship application or independent survey) and realizing that beyond direct client contact and supervision there is disagreement on which activities should count (scoring psychological tests, report writing, attending staff meetings, peer supervision, etc.), the average total number of practicum hours now reaches around 1,800 hours, the equivalent of 1 full year of supervised experience.

The Role of Supervision in Training

One of the hallmarks of professional psychology training is the introduction of the direct supervision of students’ clinical skills, typically on a one-to-one basis with a clinical supervisor. The supervisory relationship has been a rich source of study in professional psychology, and numerous models abound regarding stages and styles of supervision that foster skills and the development of professionalism. Most important, however, is the potential to work directly with a mentor and begin more self-directed learning as a budding psychologist. Supervision as a direct form of training will continue throughout internship and the postdoctoral supervision sequence and will serve as one of the major avenues for fine-tuning a variety of clinical skills before launching as a licensed professional psychologist.

Typically, supervision takes the form of case review by direct observation or video or audiotape of sessions with one’s supervisor, and students can expect to meet in direct supervision at least once a week. Other supervision may take the form of case review involving either the practicum group or agency staff. In all, students can expect that their early clinical work will be closely scrutinized and that they will have the opportunity to consult regularly with their supervisors as required. Finally, a practicum journal is often a part of course requirements and, among other training goals, helps students begin to track direct service hours with clients and patients as well as the numbers of hours of supervision received—an exercise that will lay the groundwork for tracking later internship and postdoctoral direct service and supervision hours for licensure and credentialing purposes.

Internship

One of the major defining components in professional psychology training is the internship requirement for doctoral programs in professional psychology. Typically, the internship occurs after completion of course work and required practicums and precedes granting of the doctoral degree. The internship year is designed to strengthen and refine existing basic competencies as well as introduce new or more advanced competencies that are expected of a newly licensed professional psychologist.

Certification Mechanisms for Assessing Programmatic Competence of Internship Training Programs

As mentioned earlier, assessing professional competence through certification mechanisms is an important part of both self-regulatory and external regulatory components of professional psychology education and training. In the case of internship training programs, four major professional psychology mechanisms are involved in the United States and Canada in providing basic and extensive reviews of programmatic competence level and scope. Referring to the typical doctoral education and training sequence again, these components are the APA-CPA-accredited internship, the APPIClisted internship, the Joint Committee on Internships of the Council of Directors of School Psychology Programs (CDSPP), APA’s Division of School Psychology, and National Association of School Psychologists–listed internship, and the individual approval of the internship submitted by an applicant for credentialing by the National Register.

APA-CPAAccreditation of Doctoral Internships

Both APAand CPAconsider doctoral internship training to be a capstone experience in the formalized doctoral training component prior to awarding of the doctoral degree. Testifying to its central importance, the CPA accreditation manual (1991) notes the following:

The internship is an essential component in the preparation of the doctoral level, professional psychologist. . . . It presents the opportunity for a more sophisticated integration of graduate education, psychological theory and professional skills. The internship serves as an important step in the socialization process of the professional psychologist. . . . The preparation of a doctoral level professional psychologist is facilitated by exposure to experiences in the evolution of personal growth and in the evolution of dysfunctional clinical or adjustment entities over time. The internship contributes to this experience by requiring a full time experience for one calendar year or a half time experience over two years, comprising in either case a minimum of 1600 hours. (p. 17)

Similar descriptors exist for the APA with regard to internship training and reflect the intent that program accreditation of internship training is an important indicator of a quality programmatic training environment.

With regard to actual accreditation procedures, CPA and APAdiffer somewhat in their respective approaches. CPA accreditation of doctoral internships is based on a criterionbased certification of program quality and addresses a series of five major criteria and 33 subcriteria that the internship setting must or ideally should possess in order to be accredited (CPA, 1991). APA, on the other hand, has moved to an outcomebased model and congruence philosophy of accreditation for training programs (APA Council of Representatives, 1996). As an example of this (eight-) domain approach for professional psychology internship accreditation, Domain B (Program Philosophy, Objectives and Training Plan) of the APA 1996 Guidelines and Principles forAccreditation of Programs in Professional Psychology states the following:

The program has a clearly specified philosophy of training, compatible with the mission of its sponsor institution and appropriate to the practice of professional psychology. The internship is an organized professional training program with the goal of providing high quality training in professional psychology. The training model and goals are consistent with its philosophy and objectives. (p. 12)

In the end, however, both approaches seem to offer very similar outcomes—at least in terms of accreditation status. Where Canadian doctoral programs and internships have applied for concurrent accreditation by both CPA and APA, independent decisions reached by both accrediting bodies have virtually a 100% overlap (J. Gauthier, personal communication, August 1998).

APPIC-Listed Internships

TheAPPIC was formed in the mid-1960s in the United States originally to address only internship training, and although not a formal accrediting agency, it does offer U.S. and Canadian professional psychology internship programs a paper review process that allows programs that meet all criteria and that conform to APPIC policies to be listed as an APPIC member. To quote fromAPPIC’s 2000–2001 Directory,

The Association has been organized to facilitate the achievement and maintenance of high quality training in professional psychology; to facilitate exchange of information between institutions and agencies offering doctoral internship and/or postdoctoral training in professional psychology; to develop standards for such training programs; to provide a forum for exchanging views, establishing policies, procedures and contingencies on training matters and selection of interns, and resolving other problems and issues for which common agreement is either essential or desirable; to provide assistance in matching students with training programs; and to represent the views of training agencies to groups and organizations whose functions and objectives relate to those of APPIC. (R. G. Hall & Hsu, 2000, p. 1)

For APPIC listing, internships that either are accredited by APA or CPA or otherwise meet the current 14 APPIC criteria may be listed. This process of approval could also be considered a designation process because it is parallel to that performed with doctoral educational programs by the ASPPB’s National Register Designation Project.

Perhaps the most important APPIC function is the matching of students with training programs through its uniform application procedure and computerized matching service. This newly instituted service follows the matching programs already in existence for a number of other health care disciplines and now allows both professional psychology students and internship training programs a more streamlined and orderly matching process. In terms of match results, APPIC match statistics suggest that about half of all matched applicants received their top-ranked choice of sites and that about 80% of students match with one of their top three sites.

In all, more than 80% of the 3,000-plus U.S. and Canadian match applicants in 2001 ended up matching with an internship program (APPIC, 2001), and in terms of supply and demand, it appears that there has been somewhat less disparity over the last few years between excess supply of applicants and available internship sites in the United States. (Canada generally remains balanced with regard to available applicants and internship sites.)

A corollary of APPIC is the Canadian Council of Professional Psychology Programs (CCPPP), but the latter represents both internships and doctoral programs. CCPPP sends a representative to the APPIC Board of Directors meetings and to the Council of Chairs of Training Councils to facilitate solution of problems as they arise for Canadian students and to find ways to harmonize the Canadian standards and procedures with those in the United States. There are 40 internships listed on CCPPP’s Web site at www.usask.ca/ psychology/ccppp.

Directory of Internships for Doctoral Students in School Psychology

In order to promote awareness of training sites for doctorallevel school psychologists, the CDSPP approved in 1983 and revised in 1998 the Guidelines for Meeting Internship Criteria in School Psychology. Individual sites submit an entry for the yearly directory and attest to the fact that their site meets the CDSPP guidelines. Then the CDSPP, School Psychology Division 16 of APA, and the National Association of School Psychologists, through a jointly supported committee, publish a list of internship sites that provide training appropriate for school psychologists. The impetus for this initiative was the small number of sites available generally, with no APA accredited internships in school districts at the time that this effort began.

The CDSPP guidelines are based on the National Register criteria modified slightly to meet school psychology needs, based on consultation and assistance provided by the National Register. Over the past 18 years, the National Register worked with the CDSPP to articulate how students completing such sites can be credentialed by the National Register. The main differences between the CDSPP and the National Register guidelines are the accommodation of the possibility of only one intern at a site and the cosigning of intern reports by the supervisor, as well as the requirement that the internship occur prior to the granting of the degree.

Based on the 2000 edition of this directory, 36 school sites report being APA accredited, and an additional 69 are listed, representing a total of 376 full-time and 49 half-time positions available. Updates are conducted yearly, and as of this writing the list of internships is not available online.

National Register Approved Internships

The National Register created the first criterion-based model for evaluating internship training. The history of the National Register’s involvement was prompted by the need to approve internships submitted by applicants for credentialing as a health service provider in psychology. As a result of the large number of quite varied training experiences submitted to meet the internship criterion, in 1980 the Appeal Board of the National Register developed the Guidelines for Defining an Internship or Organized Health Service Training Program in Psychology (National Register, 2000, pp. 13–14). APPIC then adopted these criteria for use in their review of internship programs; APA incorporated these criteria in their internship accreditation standards; and, more recently, CDSPP modified these criteria to meet their special needs. However, the APPIC, APA, and CDSPP require the internship to occur prior to the granting of the degree.

In 1990 the National Register reviewed every file of its 16,000 psychologists and developed a comprehensive list and classification of all the internship training programs completed by those psychologists. This is a unique database that provides a snapshot of internships over a 50-year time period, most of which were not accredited.

Postdoctoral Training and Accreditation

After successful completion of internship training and the completion of all other doctoral requirements, the student is awarded the doctoral degree in professional psychology. At this juncture most new doctorates seek postdoctoral supervised experience, whereas others may pursue a formalized postdoctoral training experience, all for the purpose of meeting the state license requirement of a year of postdoctoral experience. The history of formalized postdoctoral training is relatively recent in the United States, and APAhas essentially just begun the accreditation of postdoctoral residencies (or fellowships). For example, whereas there are approximately 570 internship programs participating in APPIC, only 66 agencies offer postdoctoral fellowship training (R. G. Hall & Hsu, 2000). Canada also offers the rare formalized postdoctoral training opportunity in some settings, but there is as yet no concomitant accreditation mechanism through CPA, and no Canadian postdoctoral training programs have yet listed with APPIC.

Much like the earlier history of internship training, formalized postdoctoral training is just beginning to come into the mainstream of professional psychology. In the case of postdoctoral training, however, the needed groundwork development for generic advanced and specialty training came via proactive involvement from a number of national professional psychology organizations in both the United States and Canada. Following on the draft standards created at the Ann Arbor Conference on Postdoctoral Residencies in Professional Psychology, the Interorganizational Council (IOC) formed by seven North American psychology bodies met for five years and produced standards and procedures that later led to the 1996 APA adoption of the eight domains and numerous standards now required for the APA accreditation of postdoctoral training programs for professional psychologists. Room exists within these structures to accommodate both generic advanced training and specialty training, depending on the postdoctoral program’s requirements and content. APAhas now approved six residencies in the advanced general area. Specialty residencies have yet to be accredited by APA, although clinical neuropsychology has adopted and tested its own standards. Again, accreditation is voluntary for postdoctoral training programs.

Based on the success of the IOC, another U.S./Canadian interorganizational professional psychology group known as the Council of Credentialing Organizations in Professional Psychology (CCOPP) began work on developing a conceptual model and taxonomy of specialization for the area of health service psychology (Drum, 2001). In general, work by such groups as IOC and CCOPP represent a shift toward a more North American–integrated formulation and enactment of professional psychology training designed to lend greater coherence to competency-based outcomes for general practice and other specialization routes for professional psychologists.

APA Commission on Education and Training Leading to Licensure in Psychology Versus Current APA Policy

Since 1955 APA has promulgated two additional models for what should be required education and training for professional psychologists. The latest (APA, 1987) specified that by 1995 an applicant for licensure must have been graduated from an APA accredited program or from a program that met the standards of the board (in most instances this would be an ASPPB- or National Register–designated doctoral program in psychology). In addition, the applicant was to complete 2 years of supervised professional experience, one of which was postdoctoral. Note that the emphasis was on the timing of the experience, with no reference to completion of an internship. The internship was left to the doctoral programs to regulate. In addition, these standards were written broadly so that all specialties could be eligible for licensing.

Over a dozen years later, the landscape has changed. Students are completing a year of practicum experience prior to internship so that they are more competitive in the internship match. Increased numbers of health care practitioners are competing for the same health care dollar and providing what they consider to be the equivalent service provided by psychologists. A significant portion of the clinical, counseling, and school psychology programs is now accredited. Internship programs are increasingly seeking APA accreditation. The training requirement is due for reexamination from a competency perspective. The question really is, At what point is basic readiness for independent practice achieved?

To begin addressing that question, a presidentially appointed commission of 30 individuals met twice in 2000, chaired by the president elect of APA, Norine Johnson, and staffed jointly by the practice and the education directorates of APA. The draft statements of the commission and the strategies for implementation have been circulated for comment by internal and external bodies affected by the potential policy. The major suggested modifications to APA policy include setting the standard of an APA-CPA-accredited internship or one that meets APPIC or CDSPP guidelines being required for a license, and by 2010 requiring all internships to be accredited. The second major suggestion relates to the 2 years of experience required for the license. One of the 2 years of experience could be completed prior to the degree, as long as the internship is completed prior to the granting of the degree. The commissioners were not suggesting the elimination of the year of postdoctoral training. In fact, postdoctoral education and training are emphasized as an important part of the continuing professional development and credentialing process for professional psychologists (APA Commission on Education and Training Leading to Licensure in Psychology, 2001).

This proposed policy threatens established structures and thus has met with resistance from some organizations committed to the requirement of the postdoctoral year of experience for licensure. One of the arguments is that it took 20 years to get that standard enacted in most states; to change it now might have a costly impact on the standing of the profession of psychology and destabilize the consensus around having a national standard for some time to come.

No matter what the outcome is of the deliberations and debates around this issue, it promises to have a major impact on APA’s position on the standards for education and training leading to licensing and perhaps even the standards legislated by states for entry to the profession.

Developing Standards for the Regulation of Professional Psychology

Essential to defining, evaluating, and promoting the education, training, and credentialing of psychologists is incorporation of the opinions of those affected by the services or training provided—the faculty, the institution, the students, the graduates, the users, and consumers. Following consensus about educational standards, self study, on-site peer review, and a review of internal and external assessments by those affected, a decision is made regarding adherence to those standards as part of the process of accreditation, which is defined as a “nongovernmental process of quality assessment and assurance applied to general, technical, and professional programs and institutions of higher education” (Nelson & Messenger, 1998, p. 4).

Accreditation is only one example of self-regulation (Drum & Hall, 1993). Consensual agreement among the various constituencies is difficult, time-consuming, and expensive. It may be easy to identify difficulties with particular approaches and recommend changes. It is another thing to accomplish those changes. Then, once standards are established, a subsequent modification threatens established structures. Examples of continuing debate topics are the doctoral-level standard for entry to the profession versus the master’s level and, more recently, the requirement of a postdoctoral year of experience for admission to licensure (APACommission, 2000).

APA Accreditation: Public Accountability Leading to Outcomes Assessment

A major change in the APA accreditation process has taken place in the past dozen years, stimulated by a national meeting in 1990 of relevant constituencies to suggest changes to the accreditation process, including the broadening of input to the Committee on Accreditation (COA; Sheridan, Matarazzo, & Nelson, 1995). There were many changes made, including the decisions to render the COA—to the greatest extent possible—independent of forces external to its own operating policies and procedures in the accreditation review and recognition of individual programs and to increase the COA’s responsibility in the formulation of accreditation policies and procedures based on good practices of accreditation nationally (P. Nelson, personal communication, May 2001). In addition, the COAwas to be expanded from 10 to 21 members representing various domains. The APA guidelines and procedures for accreditation were revised and approved in 1996, and they are still being amended.Although public accountability was hardly a new concept, these guidelines and procedures emphasize quality by measuring program goals and outcomes, focusing on competencies rather than curriculum, and stressing self-study rather than external reviews. The influences that brought all those changes were many. The COA outcomes model was a compromise among converging and diverging forces operative within the professional practice and credentialing community, professional educators and trainers, and the educational institutions in which accredited programs are hosted (P. Nelson, personal communication, May 2001). The U.S. Department of Education, which recognizes accrediting bodies such as theAPACOAfor purposes of student financial aid under Title IV of the Higher Education Act, played a role in this process by including in their 1994 regulations a requirement that student achievement be measured in terms of course completion, state licensing examination, and job placement rates (U.S. Department of Education, 1994). However, the major influence occurred earlier in 1991 by APA’s participation in the Council on Postsecondary Accreditation (COPA), a private, voluntary accreditor of the accreditors that no longer exists. (The function previously served by COPA had been partially replaced by the Council on Higher Education Accreditation, or CHEA.) In 1999 “targeted changes were made . . . to enable the COAto come into full compliance with the [U.S. Department of Education] regulations for recognition of accrediting agencies.” (APA, 2000, foreword)

Although this topic is too complex for complete exposition here, the reader can get a flavor of the energy placed on defining the proper education and training by examining some of the attempts to bring organized psychology together. Often, the term organized psychology is used to describe the coming together of different constituencies for the collective good. To define these issues, organized psychology typically appoints task forces, holds conferences, and invites representatives to address definitional issues and set standards. In order to understand the development of professional psychology, it is helpful to revisit briefly its early history.

The Historic Road to Modern-Day Licensing and Credentialing of Professional Psychologists

U.S. psychology emerged as a profession following World War II. The Veterans Administration (VA) and the Public Health Service (PHS) needed a way to identify acceptable education and training programs in clinical and counseling psychology, whose graduates were needed to serve veterans returning from the war. The choice for conducting a system of quality control was between a federal government agency or the APA. APA answered by accrediting the first set of programs in 1948 (Sheridan et al., 1995). At the same time, graduatess of programs sought recognition as psychologists. There were two mechanisms available: a short-lived state association certification process in a few states and specialty certification by the American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP). The first state licensure law was passed in 1945 and was followed soon by several others. Thus, within a short time in the United States, accreditation of doctoral programs in psychology and the concomitant licensing and credentialing of psychologists began.

However, unlike the medical profession, these laws did not require the completion of an accredited psychology program. Partly because psychology is an academic discipline and a profession, the requirement of graduating from an accredited program has been more of an aspirational standard that is restricted to programs in professional psychology, defined eventually as clinical, counseling, and school psychology. Credentialing of psychologists also began as a voluntary activity but increasingly became required for certain roles as each state passed a licensing law. As a result, exceptions in the law often allow persons with doctoral degrees in psychology to refer to themselves as psychologists and their work as psychological (e.g., those in state, academic, or industrial settings). Organized psychology was unwilling to make the commitment that other health care professions made, which required graduates to complete an approved program and become licensed. Many exemptions remain even today, more than 56 years after the passage of the first licensing law.

The small number of U.S. programs initially applying for accreditation underscored the fact that accreditation was voluntary. Psychology licensing laws, in turn, allowed individuals to be licensed as psychologists on the basis of a wide range of credentials and degrees. Recognizing that psychology was behind other professions in regulating the education and training sequence required for entry to practice, in 1976–1977 two U.S. national conferences on education and training in psychology convened by APA and the National Register brought together organized psychology to establish guidelines for the identification of doctoral programs in psychology for credentialing purposes (Wellner, 1978). This effort intended to present a unified front to state legislatures as to who was a “psychologist” by defining the required educational curriculum. The Guidelines for Defining a Doctoral Program in Psychology were adopted as the standard for evaluating programs by the National Register and ASPPB and, as a result, had a major impact on licensing and credentialing standards. The foundation knowledge areas for practice were also incorporated formally into the 1979 APA accreditation criteria.

In 1980 the National Register used the designation criteria (as they became known) to review all doctoral training programs purporting to train psychologists and published the first list of designated doctoral programs in psychology. This occurred for two main reasons: One was the absence of agreement on the admission criteria for licensing of psychologists, and the other related to the dissatisfaction in using a more qualitative review process (accreditation) for licensing purposes. The latter dissatisfaction emanated primarily from variability in the curriculum content of graduates from APA accredited programs.

With the federal and private health care systems seeking qualified providers, with variable criteria for definition of an acceptable program, and with more practitioners outside and inside psychology competing for the health dollar, the standard of completing an accredited or designated program in professional psychology was increasingly being included in state legislation. The “other” or “equivalent” category, which had been described as a euphemism for “not psychology,” began to disappear from state laws. Because the designation criteria are applicable to any area of professional psychology, designation gave licensing bodies a mechanism for evaluating programs that APA accreditation did not. A current list of programs meeting the designation criteria is available at www.nationalregister.org.

Parallel development of internship criteria occurred when internship training was defined as a component essential to the Boulder model. Accredited internship programs in professional psychology appeared in 1956. As a result of the variability in training experiences submitted by licensed psychologists to meet the internship criterion for credentialing by the National Register, in 1980 the Appeal Board of the National Register developed internship criteria, and these were adapted by APPIC, APA (1979), and CDSPP to meet their own needs.

Today, most graduates of professional psychology programs become licensed as psychologists. Licensing criteria are set by each jurisdiction but are greatly influenced by guidelines for state legislation of the APA in 1955, 1967, and 1987 (APA, 1987; APA Committee on Legislation, 1955, 1967). In 1992 the ASPPB adopted its own model of state legislation. As a result, completion of an APA-accredited or ASPPB-National Register-designated program now meets the educational requirements of most state licensing statutes and regulations. Many states require an internship, but all states except one require a year of postdoctoral experience for a license.

Canada has not adopted these criteria as universally as has the United States and does not have its own model legislation guidelines. The CPA accreditation program, begun in 1984, reviews both Canadian programs and internships and now encourages Canadian programs to apply for CPA accreditation first with the understanding that APA may recognize CPA.

The Licensing Process

Licensing laws were established to define the practice of the profession; to set educational, training, and examination standards for the profession; and, most of all, to assist the public in identifying who is qualified to practice the profession. This is different from saying that the license assesses quality. Being licensed provides the potential consumer with the reassurance that the state, province, or territory has determined that the individual has met minimal standards.

There are now 62 jurisdictions in the United States and Canada that regulate the practice of psychology or the title of psychologist. Both types of laws attempt to protect the public by clearly identifying who is qualified to practice as a psychologist (practice act) or present as a psychologist (certification of title act). Stromberg et al. (1988) explained the difference best in the following:

Licensure is a process by which individuals are granted permission to perform a defined set of functions. If a professional performs those functions (such as diagnosing or treating behavioral, emotional or mental disorders) regardless under what name (such as therapist, psychologist or counselor), he is required to be licensed. In contrast, certification focuses not on the function performed but on the use of a particular professional title (such as “psychologist”), and it limits its use to individuals who have met specified standards for education, experience and examination performance. (pp. 1–2)

Only a small number of jurisdictions have true licensure laws. The majority have certification laws, including those called permissive acts, requiring the person to be licensed if he or she practices psychology and uses the title. We use the term license to refer to either type of regulation.

Legislation also differs with regard to which psychologists are covered. Generic laws, such as in New York, require persons presenting themselves as psychologists, regardless of specialty area, to be licensed unless otherwise exempted. However, in a jurisdiction with a “health service provider” or “clinical” type definition of practice, only psychologists with that education and training sequence would even qualify for a license. Thus, industrial and organizational psychologists would not be eligible. However, exemptions to the statute may allow other psychologists to practice. Some states have a two-tier process by which the individual is first licensed as a psychologist and then may be certified as a health service provider. Specialty licensing, though attempted in certain jurisdictions, is rare, with the exception of the title of school psychologist, but entry is typically at the master’s level (exceptions are Texas and Virginia).

In Canada the regulatory laws are generic, requiring any practicing psychologist to be “registered,” “chartered,” or “certified” (the terms often seen in Canada). “Health service provider in psychology” is restricted to the voluntary listing of registered psychologists who meet the application criteria for the Canadian Register of Health Service Providers in Psychology. No specialty licensing exists in Canada.

Education and Training Requirements

Degree

The degree required for independent practice in the United States is the doctorate, with the exception of Vermont, West Virginia, and now Kentucky, where entry is available with a master’s degree.Asignificant number of states (approximately 40) also have provisions for recognition of the master’s-level trained person, although not for independent practice.

In Canada approximately two thirds of the 12,000 registered psychologists have entered practice at the master’s level. In addition, approximately 40% of the psychologists in Canada reside in Quebec, where the minimum educational requirement for a license includes completion of a Master of Professional Studies degree (MPs). Several of the Canadian provinces were originally doctoral entry only. With the exception of British Columbia, all provinces either admit to independent practice at the master’s level or allow practice at that level with some restrictions and a different title (Ontario). When one considers professional practice in North America, only the United States adheres to a doctoral degree entry standard as policy.

Curriculum

Psychology also varies from other professions in that the curriculum requirements are not as consistent as found in medicine, social work, nursing, and other health care professionals graduating from professional schools. When U.S. licensing began, the degree completed was a Ph.D., typically from a department of psychology in the college of arts and sciences in a major university. The curriculum was designed to train a researcher, even though many of the students were asking for training for practice. This need eventually led to the creation of U.S. practitioner degree programs. This PsyD offered students an option similar to the medical degree (MD). However, some of the larger professional schools granted a PhD, which led to confusion about the meaning of the PhD.As the PsyD became more accepted, those same professional schools added a PsyD track to parallel the PhD track in the same specialty area. Today, the largest number of graduates in psychology comes from professional schools, and soon the number of PsyDs granted will equal the number of PhDs awarded (Belar, 1998). The other degree in psychology, the doctorate of education (EdD), is now becoming increasingly rare.As a result of these three degrees, most licensing statutes say a “doctoral degree in psychology” rather than name a specific degree.

Experience

The 2 years of experience required for licensure, which is the norm today, typically specifies that one of those years include a year of postdoctoral experience. At that point any similarity among the 62 standards for the 2 years evaporates. There are standards for internships that are fairly universal; however, there is no consistent standard for the year of postdoctoral experience (ASPPB, 2001).

As noted earlier, whether those standards should remain the same is under debate. Not being able to practice independently on receipt of the doctoral degree puts psychology graduates at a disadvantage in the marketplace in competing not only against doctoral-level providers such as physicians but also against master’s-level providers such as social workers and counselors.

Examination Components: Exam for Professional Practice in Psychology and Oral-Jurisprudence Exams

After meeting the education and training requirements, the license applicant takes the Exam for Professional Practice in Psychology (EPPP). The exam is available throughout the year in a computer-generated version, with four forms available at any one time. This examination is properly validated through multiple studies on psychologists in the United States and Canada, including the original job analysis by Rosenfeld, Shimberg, and Thornton (1983) and the recent practice analysis conducted in 1995. For more detailed information, visit www.asppb.org.

Of the 15,095 exams administered in 1997–1999, 81% of the candidates reported that they had a doctoral degree (data are available from ASPPB Web site). In a separate analysis approximately 89% of the doctoral psychologists taking the examination reported that they completed anAPAaccredited program (ASPPB, 2000). The national pass point is 70% of the items correct, typically only for the doctorallevel candidate, and this has been adopted by the majority of members of the ASPPB, the association that develops and sells the exam to the member jurisdictions. Not all jurisdictions require the exam (Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Northwest Territories); not all have adopted the recommended pass point (Washington, DC, Maryland, North Dakota, and South Dakota in the United States, and New Brunswick in Canada); and most use a lower pass point for the master’slevel candidate.

Following a successful performance on the EPPP, there may be an oral or a jurisprudence exam, or both. In general, these exams are developed and administered by the licensing body and have not been subjected to psychometric validation. The oral exams also differ greatly in the degree of structure and the approach, in many instances involving only an interview. These complementary exams give the board the opportunity to assess what they believe is lacking in a multiple choice exam; offer the opportunity to meet each potential licensee, depending upon the size of the jurisdictions; and, because few fail, are rarely challenged.

License Maintenance Requirements

Adherence to Ethical Standards and Jurisdictional Regulations

The licensed psychologist is required to adhere to ethical and professional standards, with the former referring to the APA or CPA codes of ethics and the latter to any regulations developed by the jurisdiction. Failure to adhere to these standards if followed by a complaint to the licensing body may bring about an investigation and prosecution. If found guilty, the license may be restricted in some material way. If the psychologist is disciplined, there may be ramifications in terms of provider status (e.g., potential removal from the HMOPPO provider panel of a health care organization or from Medicare provider status), professional and credentialing status (e.g., sanctioned by APA, National Register, or ABPP), or malpractice coverage.

Continuing Education

Another component in maintaining a license to practice is the requirement for continuing professional education. In the United States and Canada 44 of the 62 jurisdictions require the licensee to complete a certain number of hours in continuing education (CE) for renewal of the license. This requirement makes sense in theory, given that professionals may practice for 40 years after receiving their degrees. However, the course quality and level of sophistication vary, and actual learning achievement is typically not measured. Credits are awarded if the participants complete the course evaluation form, regardless of whether they learned anything that was useful to their practice.

The only formal study of the effectiveness of CE for a professional took place in New York by the state board for the certified public accountants profession. The New York State Board of Regents took the position that if a profession wanted to require CE for renewal of a license, the profession needed to undertake a study of the CE requirement and fund it out of licensing fees, as the members of the CPAprofession were required to do. However, this study did not examine whether what was studied improved practice; it examined the impact on knowledge (J. E. Hall, 1993). To date, the New York State Board of Regents has not approved a CE requirement for psychology.

Mobility of the Psychologist’s License to Practice

Once an individual is licensed to practice, it would seem logical that any subsequent license would be relatively easy to get, should the individual move or need to be licensed in another jurisdiction (assuming that there is no history of discipline). Clearly the licensed psychologist has to complete an application and pay the fee. However, the jurisdiction may also require primary source verification of credentials and submission of the applicant’s EPPP score. While the state or province to which the psychologist is applying has the responsibility to protect the public, the verification process may place incredible barriers or lengthy delays on people who have been licensed, often for years, without any incident.

Reciprocity Agreements

Several professions, not just psychology, have recently attempted to facilitate mobility of licensed practitioners by two basic methods: multijurisdictional agreements or individual endorsement of credentials. Reciprocity agreements involve the acceptance of licensees without question. For instance, Texas currently has a reciprocity agreement with Louisiana. That means that anyone licensed in Louisiana could be licensed automatically in Texas and vice versa. These agreements are legally binding until rescinded. Although this may be acceptable from the psychologist perspective, the idea that a licensing body has no control over each person who would be licensed in that jurisdiction causes boards to avoid such agreements. Even after ASPPB put enormous resources into encouraging jurisdictions to sign on to its reciprocity agreement, only 10 have done so. A few that signed it later withdrew. One difficulty is that the agreement often necessitated the jurisdiction’s changing its law to meet the contractual specifications, including conducting an oral examination. California has eliminated its oral examination as of January 2002, even though it has had a long history of oral examinations.

Credentials Endorsement Agreements

Another form of mobility is offered through use of individual credentialing mechanisms that employ recognized national standards and reflect primary source verification procedures. Expediting the granting of a license to a person because he or she possesses a credential involves endorsement of that credential. One of the earliest examples is ABPP and the diploma privilege. If a state accepts ABPP for endorsement purposes, it usually involves waiver of the license examination, either the oral or the EPPP, on the basis of the applicant’s having previously taken the ABPP exam. Although 34 states have this provision, ABPP has 3,200 active diplomates, so endorsement affects a small portion of psychologists.

In the late 1990s an individual mobility certificate was created by ASPPB, the Certificate of Professional Qualification (CPQ). Although it is new, few people have applied for the CPQ, even though it recently completed its 2-year grandparent period, which allowed licensees without doctoral degrees in psychology to qualify. By the conclusion of the grandparent period on December 31, 2001, approximately 4,000 applications were received. The requirements of the CPQ involve the jurisdiction’s accepting these certificate holders without implementing any additional barriers other than a jurisprudence examination, although Ohio requires that the transcript still be submitted. For more information, visit www.asppb.org.

Another approach to facilitating mobility is to use an established credential such as the National Register, which applies to 14,000 psychologists, for endorsement. As primary source documentation of education, training, licensing, board certification, and proficiency certification are on file, a growing number of jurisdictions have agreed. These psychologists have taken the licensing examinations required by at least one jurisdiction and have been monitored for disciplinary activity while credentialed by the National Register. For more information, visit www.nationalregister.org.

Government-Initiated Agreements

In Canada, because of the Agreement on Internal Trade, movement of professionals across Canada will be based on demonstrating the requisite competencies. In order to develop an agreement that met with acceptance by professionals and the government, psychology established a working group. After several years of work and a lot of negotiation, the Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) became effective June 24, 2001, and includes several fast-track mechanisms for granting a license to psychologists: (a) holding the Canadian or National Register Health Service Provider in Psychology credential, (b) having graduated from a CPA- or APAaccredited doctoral program, or (c) holding the CPQ. Any psychologist licensed for 5 years in 1 of the 11 signatory jurisdictions prior to July 1, 2003, may also be licensed. In addition, psychology regulatory bodies agree to perform a competency assessment of applicants for a license beginning July 1, 2003. Although consonant with the intent of the provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), this agreement goes beyond harmonization of education and training that Canada, the United States, and Mexico may negotiate under NAFTA. Visit www.cpa.ca for a copy of the MRA.

Another example of facilitating mobility exists in Europe. As a consequence of a country’s membership in the European Union (EU), regulated professionals are free to move and practice in another country participating in the EU. The main barrier to practicing in another country is language. However, if language is not an issue and the practitioner has met standards in one country, he or she can practice in another country for a year without any restrictions and regardless of the disparity in the two sets of standards. However, after that time period, the individual may be required to make up certain deficiencies for the right to continue practicing in the second jurisdiction.

Certification by Private Credentialing Organizations

Once licensed, psychologists have the opportunity to be credentialed for specific purposes. These voluntary credentials are chosen by a portion of those who are potentially qualified, and not to the degree as they are in medicine, where 80% of physicians are board certified (J. E. Hall, 2000). These voluntary credentials may have standards that are higher than is required for a license.

Therefore, the goal of licensing—to serve the public need—is furthered by credentialing organizations’ assessment of specialized education and training and specialty competence. At the same time, these voluntary certification bodies are dependent upon licensing for certain protections, such as the investigation of complaints of professional misconduct. . . . Neither licensing nor certification alone is sufficient as a mechanism to protect the public and ensure minimum competence; both are needed. (J. E. Hall, 2000, pp. 317–318)

The typical doctoral sequence (as noted in Figure 20.1) reflects the credentialing organizations that are members of the CCOPP. There are also many other credentialing organizations that exist for psychologists, although many are small, have no central office or full-time staff, may credential multiple disciplines, have no publicly available list of credentialed practitioners, and fail to meet the standards met by the credentialing organizational members of CCOPP. Because of the existence of “unrecognized” or “undesignated” credentialing organizations, the public, including psychologists, needs to be wary of relying on such credentials and seek out those that are generally accepted in professional psychology. With those concerns in mind, we chose to focus on the National and Canadian Register, ABPP, and the College of Professional Psychology.

National and Canadian Registers of Health Service Providers in Psychology