Sample Crisis Intervention Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

During the course of a lifetime all people experience a variety of personal traumas, such as divorce or illness, and many others will also live through cataclysmic events, such as natural disasters or acts of violence, that result in a state of crisis. An underlying assumption of crisis intervention theory is that crises are universal and can and do happen to everyone (James & Gilliland, 2001). International media coverage of earthquakes, floods, famine, war, and acts of terrorism provides poignant reminders of this fact.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The difference between a disaster and an accident is a matter of degree. In a disaster, the social structure is adversely affected, which in turn threatens the existence and functioning of an entire group, in contrast to the experience of individual trauma that results from an accident or act of crime (Eranen & Liebkind, 1993). The worldwide prevalence of people traumatized by disaster and war, terrorism, intrafamilial abuse, crime, and rape, as well as school and workplace violence, is significant. Indeed, some researchers found that approximately 40% of all children and teens will experience a traumatic stressor and that the lifetime prevalence for trauma exposure may be as high as 90% (Breslau et al., 1998; Ford, Ruzek, & Niles, 1996).

It is generally recognized that exposure to traumatic stressors without effective psychological intervention can trigger adverse, long-term effects that can become extremely difficult to resolve as an individual moves through subsequent developmental stages. The timely delivery of appropriate treatment is imperative during the acute crisis phase to mitigate the potential for psychopathological sequelae, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

However, it is important to note that not all individuals suffer physical and psychological deterioration in the aftermath of a crisis. Although exposure to traumatic stressors can be potentially hazardous to an individual’s well-being, crisis states can also provide an avenue for personal growth (Tedeschi, Park, & Calhoun, 1998). In fact, Gerald Caplan, the founder of modern crisis intervention, argued that crisis is a necessary precursor to growth (1961, p. 19). The coping process, a time during which an individual strives for equilibrium or stability in response to a stressor, provides a venue for achieving either a higher or lower level of functioning than the precrisis state and creates a foundation for future development.

The idea that crisis can result in a positive or negative outcome is illustrated by two Chinese characters, one symbolizing “danger” and the other “opportunity.” When combined to createtheword“crisis,”thesesymbolsconveythepotentialas well as the dual meaning of the word. In the English language, the word “crisis” is derived from the Greek word “krinein,” which translates as “to decide.”As with the Chinese character for “crisis,” derivatives of this term also capture the idea that the potential for either a detrimental or a beneficial outcome exists in the aftermath of a crisis.

Researchers and mental health clinicians have developed a number of definitions for the word “crisis” in the English language. In general, each of these definitions conveys a number of common concepts: Exposure to a traumatic or dangerous event leads to acute distress, which results in psychological disequilibrium, a state wherein the employment of familiar coping strategies has failed, creating the potential for cognitive, physical, emotional, and behavioral impairment.

Crisis intervention services are now widely recognized as an efficacious treatment modality for the provision of emergency mental health care to individuals and groups. In the past decade, there has been a proliferation of empirical outcome studies resulting in the development and refinement of a variety of effective assessment and intervention techniques. Psychologists need to be able to diagnose and treat disorders associated with trauma (e.g., PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, and depression), provide consultation to medical personnel, educate the community and other crisis intervention service providers about normal responses to abnormal events, and assist in the implementation of emergency mental health care for communities, hospitals, and community agencies. It is critical for psychologists to be well trained in assessment, to have knowledge of useful crisis intervention techniques, and to be able to work effectively with other agencies in providing emergency mental health services.

Research paper Overview

This research paper will present a summary of the historical highlights and the theoretical influences on the development of modern crisis intervention theory. As crisis intervention evolved into a recognized discipline, a number of models were developed that described, clarified, and formulated assessments and treatments used in providing emergency psychological care. These models provide the groundwork for our current understanding of crisis intervention and will be discussed along with newer models that have recently been advanced, such as Critical Incident Stress Management and Critical Incident Stress Debriefing.

Just as there are many different types of crises, health care professionals and agencies that provide crisis intervention services have developed a variety of effective assessments and treatments. An overview of solution-focused therapy, cognitive therapy, and other useful techniques will be presented, and the differences between brief psychotherapy and crisis intervention will be delineated. The differences and similarities in the delivery of emergency mental health services to individuals and groups will be highlighted.

A conceptual overview will be described, along with a framework with which to identify, assess, and treat individuals or groups experiencing a crisis. We will specifically focus on three different events. Case examples will be used to illustrate the implementation of specific assessments and interventions in providing crisis intervention services to suicidal patients and victims of natural disaster and acts of terrorism, as well as patients and families struggling with debilitating illness.

A general framework for providing cross-cultural crisis intervention will also be presented. Sensitivity to and awareness of cultural differences, along with a basic knowledge of how different cultures respond to crisis and to therapeutic intervention, are necessary in providing an effective response. Crisis intervention terminology that is commonly used by health care providers, researchers, and social agencies will be noted and defined throughout this research paper. Additionally, current research and recent trends will be reviewed along with relevant legal issues.

Finally, most psychologists providing crisis mental health services will find themselves working in conjunction with other social agencies such as the police, hospital personnel, mobile crisis units, and the American Red Cross. Typically, a psychologist works as a member of a mental health team when providing crisis intervention services at the disaster site or in a variety of mental health care settings. A description of how such teams are formed and mobilized will be provided.

History and Theory of Crisis Intervention

During World War I, Salmon (1919) observed French and English medical teams treating soldiers suffering from war neuroses. He noted that timely interventions, conducted within close proximity to the battle zone, increased the number of soldiers who were able to return to combat and reduced the degree of adverse psychiatric consequences experienced by those traumatized by battle. World War I veterans who were psychologically disturbed by combat-related trauma, but were without physical wounds, were described as “shell-shocked” and were treated for combat neurosis. The long-endorsed idea that “time heals all wounds” was first challenged during World War I and would be further disputed during World War II.

During World War II, combat-related PTSD was referred to as “battle fatigue.” The concepts of immediacy, proximity, and expectancy were acknowledged as critical elements in providing treatment to combat-fatigued soldiers duringWorld War II.The goal was to treat distressed soldiers quickly and as close to the front line as possible in order to have them rapidly return to duty. However, recent research findings based on several decades of accumulated evidence indicate that many World War I and World War II veterans experienced the first onset of PTSD, or an exacerbation of symptoms, in late life (Ruskin & Talbott, 1996). Although it is unclear why the onset of combat-related PTSD was delayed for decades, some researchers hypothesized that many older adults were underdiagnosed because these veterans did not associate their postwar difficulties with their combat experiences. It also may be that health care clinicians attributed the symptoms experienced and reported by these veterans as solely related to alcoholism, depression, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorders. However, PTSD is often comorbid; in other words, a variety of mental illnesses can and do occur with PTSD (James & Gilliland, 2000; Zlotnick et al., 1999).Additionally, late-life stressors such as retirement, death, illness, economic hardship, and declining mental and physical well-being erode existing structure and social supports that earlier in life provided a modulating influence against the onset of PTSD symptoms (Hamilton & Workman, 1998).

Veterans suffering from combat neurosis, as well as bereaved family members, were treated with interventions that were adapted from those developed earlier by Erich Lindemann, a psychiatrist, to treat grieving family members who had lost a loved one in the 1942 Coconut Grove nightclub fire in Boston. Lindemann and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital clinically observed the acute and delayed reactions of the relatives of the 492 victims who died in the fire. Although most individuals did not present psychopathological symptoms in response to the death of a loved one, some did develop acute grief reactions that appeared pathological. Lindemann (1944) found that these individuals exhibited temporary behavioral changes that were precipitated by the loss and were ameliorated by short-term interventions. He championed the idea that an individual’s expression of grief after experiencing a significant loss should not be considered as abnormal or pathological but as a normal manifestation in reaction to a traumatic stressor. Historically, modern crisis intervention theory evolved from Lindemann’s (1944) classic study of acute grief reaction.

Lindemann (1944) delineated five related normal grief reactions: (a) somatic distress; (b) preoccupation with the image of the deceased person; (c) guilt; (d) hostile reactions; and (e) the loss of patterns of conduct (Lindemann, 1944, p. 142). The extent of the individual’s grief reaction was influenced by the degree of successful readjustment to the environment without the loved one, the ability to free himself or herself from the deceased, and the facility to develop new relationships. Until this time, personality disorders or biochemical illnesses were thought to be the cause of grief-related depression or anxiety, and the provision of therapy to treat these symptoms was considered to be the exclusive domain of psychiatry. Notably, in the aftermath of this tragedy, Lindemann came to accept that community paraprofessionals and clergy could be just as effective in providing crisis intervention services as psychiatrists.

Lindemann and Gerald Caplan founded the Wellesley project, a community mental health program in Cambridge, Massachusetts, subsequent to the disastrous Coconut Grove nightclub fire, to provide crisis intervention and community outreach.An equilibrium/disequilibrium paradigm was developed that depicted the process of crisis intervention in treating an individual’s reaction to a traumatic stressor. The paradigm included four stages: (a) The individual’s equilibrium is disrupted, (b) the individual engages in grief work or brief therapy, (c) the individual experiences some resolution of the problem, and (d) the individual’s equilibrium is restored.

The rationale for crisis intervention was that the provision of guidance and support to individuals in crisis would avert prolonged mental health problems. Lindemann and Caplan believed that when people are in a state of crisis they feel anxious, are more receptive to help and suggestion, and are motivated to change. Whereas Lindemann (1944) provided the foundation for understanding and treating acute grief reactions, Caplan (1964) used the concepts to expand the use of crisis intervention strategies in treating all developmental and situational traumatic events.

Crisis, as defined by Caplan (1961), is a state that results when an individual confronts obstacles to significant life goals that cannot be surmounted through the use of normal problem-solving efforts. Psychological homeostasis describes the balance or equilibrium between the affective and cognitive experience. When a disruption in psychological functioning occurs, an individual will engage in behaviors to restore balance or equilibrium. Traumatic events can create a state of disequilibrium.

Disequilibrium is defined as a time when an individual is unable to find a solution to a problem or when normal coping mechanisms fail, resulting in an inability to restore the state of equilibrium and disrupting homeostasis. The outcome, according to Caplan (1964), is acute distress accompanied by some level of functional impairment. Early intervention was the key to encouraging the potential for positive growth and, conversely, discouraging possible psychological impairment. Possible sequelae mentioned by Caplan (1969) included depression, panic, cognitive distortions, physical complaints, and maladaptive behavior.

Four stages of crisis reaction were described by Caplan (1964). The first stage involves an increase in tension that results from an emotionally threatening, crisis-precipitating event. The second stage is a period when daily functioning is disrupted because the individual experiences an increased level of tension and is unable to quickly resolve the crisis. The third stage may lead to depression when tension levels steadily increase to an intense level and the individual’s coping mechanisms continue to fail. During the last stage, an individual may use different coping mechanisms to partly solve the crisis, or a mental breakdown may ensue.

In the late 1950s, several events accelerated the development of a diverse offering of crisis intervention services and fostered the growth of formalized crisis intervention programs. The advent of the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center, developed by suicidologists Norman Farberow and Edwin Shneidman, provided a successful template that would foster the growth of suicide prevention hot lines. In the 1960s, walk-in clinics and crisis hot lines, many of which were manned by nonprofessional volunteers, provided care for victims of rape and domestic violence and counseled those at risk for suicide.

The Short-Doyle Act, enacted by the California Legislature in 1957, laid the groundwork for the deinstitutionalization of many chronically mentally ill individuals who were placed indefinitely in locked wards of publicly funded mental hospitals. This act provided counties with funding to organize and operate mental health clinics for individuals with mental illness through locally controlled and administered health programs.The Community Mental Health CentersAct, passed by Congress six years later in 1963, was the outcome of President John Kennedy’s vision for a new approach in the delivery of mental health services. The development of a national network of community-based mental health service centers was intended to provide services to chronically mentally ill patients. Crisis intervention services would be offered as a type of preventive outreach. Caplan (1961, 1964) defined the concepts of preventive psychiatry that would guide the delivery of these newly mandated services, the objective of which was to decrease “1) the incidence of mental disorders of all types in a community; 2) the duration of a significant number of those disorders which do occur; and 3) the impairment which may result from those disorders” (Caplan, 1964, pp. 16–17).

However, the goals established by the Community Mental Health Centers Act were not achieved, because the majority of mental health services provided by the clinics were not utilized by the seriously and chronically mentally ill but were being used by individuals with emotional and psychological problems that were previously treated by psychologists and psychiatrists in private practice. As a result, many individuals with chronic mental illness were not receiving adequate treatment.

In 1968 the Lanterman Petris Short Bill was passed by Congress to address this concern, and it placed new requirements on the type and delivery of mental health services made available through the clinics. Individuals without chronic mental illness were now offered short-term crisis intervention, whereas the seriously mentally ill were provided with longterm case management services.

Dramatic changes at the policy level have brought about (some might say forced) greater cooperation within the disciplines of mental health as well as across agencies. Since the passage of the Community Mental Health Centers Act, all community mental health centers receiving federal funding must provide 24-hour crisis and emergency services (Ligon, 2000). The focus at that time was to promote a transition from mental health services provided by institutions to services provided by the community. As deinstitutionalization continued over the years and the goal became focused on helping patients stabilize over a few days rather than providing long-term care, community programs have had to rapidly expand to accommodate the increased demand for emergency psychiatric services.

Short-Term Crisis Intervention

The successful delivery of short-term crisis intervention services, coupled with the public’s growing recognition that 24-hour psychiatric emergency treatment (PET) was effective and essential in responding to suicidal, homicidal, and psychotic crises, increased both the demand for and the development of community-based services. The theoretical basis for these programs is the principles of both public health and preventative mental health treatments and does not focus on identifying and treating psychopathology. Outreach programs were developed with the goals of identifying high-risk groups, promoting community recovery, and minimizing social disruption (Ursano, Fullerton, & Norwood, 1995). Emergency suicide hot lines, rape crisis centers, battered women’s shelters, crisis intervention units, and community crisis centers flourished during the 1970s. In fact, the number of community mental health centers grew from 376 centers in 1969 to nearly 800 centers by the early 1980s (Foley & Sharfstein, 1983).

Three decades later, the short-term crisis intervention model continues to be used by community mental health centers and is also popular with health maintenance organizations (HMOs), preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and a number of insurance carriers. Managed care firms justify limiting their patients to four to six sessions with a trained mental health clinician based on their interpretation of community center program evaluations that reported that short-term interventions were as beneficial as long-term psychotherapy (Kanel, 1999). In recent years, managed care has also had a significant effect on the delivery of services at the clinical level and in the administration of mental health services.

As part of a typical managed care treatment plan, patients are frequently referred to other community services, such as Alcoholics Anonymous and community-based support groups, to augment brief therapy. In general, managed care firms find short-term crisis interventions appealing because they are cost-effective therapeutic treatments.

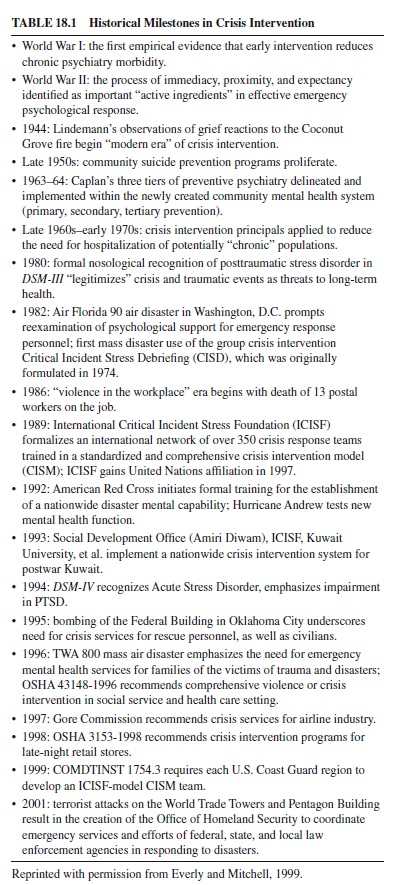

More recently, Jeffrey Mitchell and George Everly developed a comprehensive, integrative, multicomponent program, Critical Incident Stress Management. A review of Critical Incident Stress Debriefing as a component of Critical Incident Stress Management is discussed later in this research paper (Everly & Mitchell, 1999). A summary of key historical events in crisis intervention theory and service development is presented in Table 18.1.

Stress and Coping

Crisis intervention is now recognized as an effective component of a psychologist’s therapeutic repertoire for helping individuals deal with the challenges and threats of overwhelming stress. As noted earlier, all individuals experience stress in the normal course of their lives. Although stress in and of itself is not harmful, it may precipitate a crisis if the anxiety accompanying it exceeds the individual’s ability to cope.

Stress

Stressful events may adversely impact everyday functioning and potentially lead to long-term impairment. A number of factors influence personal vulnerability. These include individual differences, such as age, personality type, health, worldview, life experiences, phase of development, support system, and cultural values. Also, the timing, intensity, and type of disturbance can be significant. Moreover, people possess different levels of stress tolerance, ways of coping with adversity, and access to social supports (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Myers, 1989). An individual’s reaction to stress results from a complex interaction among these factors.

Some events that can potentially result in crisis are predictable, whereas others are not. Examples of unpredictable events include earthquakes or the sudden death of a loved one. In contrast, other situations are anticipated and gradually climax in a state of crisis. Examples include a long-distance move to another community, divorce, and death resulting from terminal illness.

Stressful events that evolve into an expected outcome offer the opportunity for gradual understanding and assimilation of the imminent loss or transition. The individual is not forced to abruptly absorb the distressing reality of an irrevocable event. A single stressful event may not be harmful, but the accumulative affects of such events over time can be intolerable. Therefore, the precipitating factor in a crisis may not be as significant as the series of events that precede it and create a vulnerable state for the person.

As noted earlier, people have different levels of stress tolerance, but cumulative crisis events exact demands for adaptation that ultimately exhaust emotional reserves, even in individuals possessing high tolerance levels. Although successful resolution of a crisis may result in personal growth and a higher level of functioning than in the precrisis state, psychic assaults from recurring, multiple crisis events would eventually lead to disorganization and disintegration of adequate coping abilities. If a person is able to cope with the stressful event without suffering subjective distress, then he or she will most likely experience stress and not a crisis.

Coping

Coping and appraisal are closely related processes. The threat appraisal process involves three components: primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and coping (Lazarus, 1966). Primary appraisal is the individual’s perception of the event. It is important to note that the perception of an event, rather than the situation itself, is different for each individual. People experience the same event differently because of individual differences (as noted above) that influence their perception of the crisis. Hence, crisis is self-defined: It is the person’s response to an internal or external event rather than the event itself. In other words, exposure to the same precipitating event may result in crisis for one person but not for another. A stressful event in and of itself does not constitute a crisis.

A crisis is determined by the individual’s perception (primary appraisal) and his or her potential response to the event (secondary appraisal). The response that is executed in reaction to the stressful event is defined as coping. Coping can be either emotion focused or problem focused (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Lazarus, 1966). The goal of emotion-focused coping is to reduce emotional distress that is associated with the situation, whereas problem-focused coping strives to alter the relationship between the person and the source of the stress. Most stressors typically elicit both types of coping. Emotion-focused coping usually predominates when people feel that the stressor is something that must be endured, whereas problem-focused coping prevails when people feel that action can be taken to alter the source of the stress (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980).

If an event is perceived as threatening, and in response the individual’s typical coping strategies fail and he or she is unable to pursue or is unaware of alternative coping strategies, then the precipitating event may result in a state of crisis, in which the person experiences feelings of helplessness, anger, anxiety, inadequacy, confusion, fear, disorganization, guilt, and agitation (Smead, 1988).

According to Roberts (2000), a crisis is “defined as a period of psychological disequilibrium, experienced as a result of a hazardous event or situation that constitutes a significant problem that cannot be remedied by using familiar coping strategies” (p. 7). James and Gilliland (2001) defined “crisis” as “a perception of an event or situation as an intolerable difficulty that exceeds the resources and coping mechanisms of the person. Unless the person obtains relief, the crisis has the potential to cause severe affective, cognitive, and behavioral malfunctioning” (p. 3).

Crises can be categorized as developmental, situational, existential, or environmental (James & Gilliland, 2001). Developmental crises arise from predictable, normal change and are internally caused situations that result from growth and role transitions, such as the onset of adolescence (Caplan, 1964; Erickson, 1950). Situational crises are externally caused situations that are unpredictable, such as the loss of a job, an accidental death, or natural disaster. The threat of loss (death, separation, illness) that occurs with a change in circumstances can precipitate a crisis reaction (Caplan, 1964). “The key to differentiating a situational crisis from other crises is that a situational crisis is random, sudden, shocking, intense, and often catastrophic” (James & Gilliland, 2001, p. 5).

Existential crisis acknowledges the turmoil of “inner conflicts and anxieties that accompany important issues of purpose, responsibility, independence, freedom and commitment” (James & Gilliland, 2001, p. 6). For example, the remorse that can accompany a person’s knowledge that certain opportunities (career, marriage, children) are no longer available at age 60 that were once options at age 30 can result in feelings of emptiness for some individuals that can be difficult to remedy. Individuals or groups of people are at risk for exposure to environmental crises that are natural or human caused, biologically derived, politically based, or the result of severe economic depression (James & Gilliland, 2001).

To maintain equilibrium, people employ compensatory mechanisms when confronted with minor challenges and disturbances. “Commonly used compensatory mechanisms might include denial of the problem, rationalization, intellectualization, creation of a psychological carapace, and/or problem solving techniques” (Everly & Mitchell, 1999, p. 24). When coping and compensatory mechanisms fail and the threat of the situation cannot be adequately resolved, then most individuals are typically unable to reestablish psychological homeostasis, resulting in a state of crisis. It is at this point that symptoms of decompensation become evident: panic (psychological and physiological symptoms), depression, hypomania, somatoform conversion reactions (deficits in the motor or sensory systems), acute stress disorder (ASD), PTSD, grief or bereavement reactions, psychophysiological disorders (medical conditions that are exacerbated or caused by extreme stress; see Everly, 1989, for an in-depth discussion of the physiology of stress response mechanisms), brief reactive psychosis, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and other crisis-related symptoms (anger, violence, suicide; Everly & Mitchell, 1999, pp. 25–32).

Flight, fight, or freeze behaviors (survival-mode functioning) are specialized cognitive-affective mechanisms that are activated when individuals are confronted with life-threatening events (Chemtob, Roitblat, Hamada, & Carlson, 1988). These behaviors are adaptive in the context of a threatening incident but are deleterious to well-being if they persist after the event. Osterman and Chemtob (1999) posit that persistence of the survival-mode functioning accounts for the clinical presentation of traumatized patients. “High levels of anxiety and avoidance are associated with flight responses; increased anger and aggression represent the persistent mobilization of a fight response; and dissociative symptoms, emotional numbing, or depersonalization reflect freeze responses” (Osterman & Chemtob, 1999, p. 739). It is essential to start working with individuals as soon as possible after a crisis to prevent this chronic cycle of behaviors from developing.

Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder was first recognized as a diagnostic category, and was classified as a subcategory of anxiety disorders, in the 1980 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). The definition of ASD was included as an independent entity in the 1994 version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The symptoms of ASD differ from those of PTSD in three ways. “The disturbance [for ASD] lasts for a minimum of 2 days and a maximum of 4 weeks and occurs within 4 weeks of the traumatic event” (APA, 1994, pp. 431–432), whereas the duration of the disturbance for PTSD is for at least 1 month (APA, 1994, pp. 427–429). Additionally, the person with PTSD experiences at least three symptoms signifying dissociation, and the dissociative symptoms may prevent the individual from effectively coping with the trauma.

The percentage of individuals exposed to severe trauma who eventually develop PTSD varies from 10% to 12%. The reader is encouraged to refer to the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) for a complete description of the criteria for ASD and PTDS. Clinicians providing crisis intervention to individuals and groups should be familiar with the diagnostic criteria for both these disorders.

Brief and Long-Term Psychotherapy Versus Crisis Intervention

Crisis theory is comprised of an eclectic mix of theoretical modalities. It draws on cognitive-behavioral, psychoanalytic, existential, humanistic, and general systems theories (Callahan, 1998; Kanel, 1999). Although a number of models have been developed to describe the intervention process, they all share two characteristics. Crisis interventions are time limited and are designed to help individuals return to their precrisis level of functioning (Gilliland & James, 1993; Puryear, 1979; Roberts, 1991). The focus is on decreasing acute psychological disturbances rather than curing long-term personality or mental disorders.Aprinciple of crisis intervention is that the person’s symptoms are not viewed as indicative of personality deterioration or mental illness but, rather, are viewed as signs that the individual is experiencing a period of transition that is disruptive and distressing but relatively brief in duration. The goal is to help individuals and groups deal with the stressful transition period. Most people in crisis realize they need aid but do not perceive themselves as mentally ill.

As noted earlier, perception of, and the meaning ascribed to, an event is a critical factor in determining whether the individual can cope. The meaning a person gives to an event has been described as the “cognitive key” with which to unlock the door to understanding the patient’s experience of the crisis (Slaikeu, 1990, p. 18). It affects what individuals do in response to the event and whom or what they blame for the incident. Meaning is dynamic, not static, and it changes over time as the context changes. By understanding the meaning of an event, clinicians can reframe their patients’ cognitions to assist them in reducing their immediate suffering, increasing their coping capabilities, and preventing long-term adverse physical, affective, and behavioral consequences.

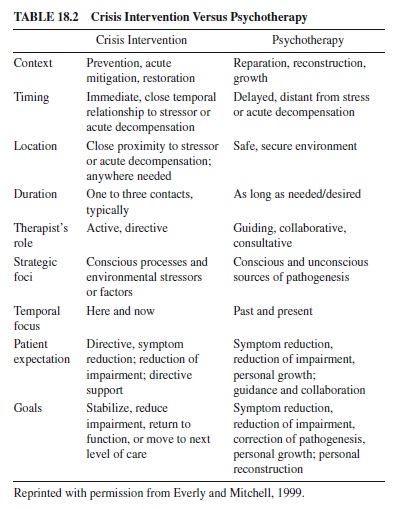

Crisis interventions differ from traditional psychotherapy in a number of significant ways. Crisis counseling typically takes place in community crisis clinics or at the site of the traumatic event, as in the case of natural disasters or violence at school or in the workplace. Crisis interventions are conducted immediately following a traumatic event, in contrast to an office-based therapy, in which patients usually schedule ongoing weekly appointments. Traditional therapy concentrates on diagnosis and treatment with collaborative goals of personal growth and improvement of functioning by encouraging insight (psychodynamic) or examination of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (cognitive-behavioral therapy). An overview of how crisis intervention differs from psychotherapy is presented in Table 18.2.

In contrast, for individuals in crisis, the focus is on understanding the meaning of the crisis, assessing the idiosyncratic characteristics of the individual, learning about the strengths and weaknesses of the individual’s support system, and adapting and developing the person’s coping skills, all with the minimal goal of restoring precrisis levels of functioning. In general, crisis interventions are directive and supportive with the goal of lessening any adverse impact on future mental health.

Wainrib and Bloch (1998) noted that because a crisis can evoke either a positive or negative reaction, it creates an environment in which one “reassesses one’s life” (p. 28). During this state people may be more receptive to new information and willing to try new coping strategies (Puryear, 1979). After a crisis, many individuals may strive to attain their precrisis level of functioning, whereas others may not be able to fully reconstruct their lives. However, some people may find that the successful resolution of a crisis serves as a catalyst that can bring about growth, positive change, and enhanced coping ability, as well as a decrease in negative behavior, resulting in a higher postcrisis level of functioning (Janosik, 1984, pp. 3–21). The acquisition of new skills and coping mechanisms to deal with the current crisis situation can foster psychological and emotional growth as well as benefiting the individual when he or she is confronted with new crisis or stressful situations in the future (Fraser, 1998).

Assessment and Intervention

Psychologists conducting standard diagnostic assessments in an office or hospital employ knowledge of life span development and psychopathology and utilize a diagnostic classification system such as the DSM-IV or ICD-10 to guide and organize their treatments.

A measurement of the severity of the psychosocial stressors experienced by the patient is noted on the DSM-IV Axis V (Generalized Assessment of Functioning). The patient’s current level of functioning is determined by the clinician from a list of identified behaviors that are ranked from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater overall functioning and coping (APA, 1994). Rating scores assigned at the beginning of treatment can be used to monitor the course of therapy. It is often helpful to compare the patient’s current level of functioning to his or her highest level of functioning attained during the past year.

Crisis workers generally do not have the luxury of time to collect and analyze medical and mental health records that might be available under normal conditions. An abbreviated assessment process, whose objective is to quickly formulate an assessment and to understand the meaning the individual has ascribed to the crisis, should include an exploration of the precipitating event and past events that were similar, because memories of past losses and bereavement typically resurface in current loss situations.

An assessment of the individual must be made in conjunction with an appraisal of the nature and scope of the crisis in order to better delineate his or her experience. Was the individual a victim or a witness? The closer the proximity (temporal and physical) to the event and the greater the degree of perceived threat, the greater the potential for adverse physical and psychological sequelae.

Psychologists working with individuals in crisis must be able to quickly evaluate the degree of disequilibrium experienced by the individual and calmly convey support, acceptance, and confidence about the future. Assessments may have to be conducted at the site of the event and may be limited to less than 15 or 20 minutes. In instances in which a group has been exposed to a traumatic event, it is often beneficial to meet for a group assessment for a longer period of time. The “norm” of the group can be quickly determined, and individuals who deviate from the norm can be identified as being at high risk for adverse reactions (Wainrib & Bloch, 1998). Specific intervention plans can then be developed that address the needs of individuals, wherever they lie on the risk spectrum. Assessment is an overarching and ongoing process that takes place during each phase of crisis intervention.

Assessment should include asking about the individual’s perception of the crisis, the sequence of events, current feelings, and a description of his or her attempts to deal with the problem. Is the individual safe? What is the individual’s emotional affect, alcohol and drug usage, and current stress level? All individuals should be evaluated on an ongoing basis to determine if they pose a threat to themselves or others.

Although a number of protocols have been developed to guide clinicians in assessment and treatment, we present the steps for three that best represent key approaches to crisis intervention. An outline of the steps Puryear (1979) recommended includes the following: (a) immediate intervention, (b) action (actively assessing and formulating), (c) limited goal (averting catastrophe and restoring growth and hope), (d) hope and expectation, (e) support, (f) focused problem solving, (g) enhancement of self-image, and (h) encouragement of self-reliance.

A seven-stage approach to crisis intervention was developed by Roberts (1991, 2000): (a) Assess client lethality and safety needs, (b) establish rapport and communications, (c) identify the major problem, (d) deal with feelings and provide support, (e) explore possible alternatives, (f) assist in formulating an action plan, and (g) perform follow-up.

More recently, James and Gilliland (2001) created a six-step, “action-oriented situation-based method of crisis intervention,” which includes the following steps: (a) Define the problem, (b) ensure client safety, (c) provide support, (d) examine alternatives, (e) make plans, and (f) obtain commitment to positive actions (p. 33). Within this framework, the clinician should assess (a) the severity of the crisis; (b) the client’s current emotional status; (c) the alternatives, coping mechanisms, support systems, and other available resources; and (d) the client’s level of lethality (danger to self and others). Although experts in this area may differ on the terms and number of steps required, they do agree that specific elements are essential and fundamental to intervention.

Planning and Implementing the Intervention

Planning and implementing the intervention occur after one has completed an assessment of the individual and the crisis. Basic concepts from each of these models include the following:

- Establishing therapeutic rapport with the person. With open-ended questions, support, and empathy, encourage expression of feelings and thoughts without lecturing or using clichés such as “I understand” or “Be strong.” Helpful remarks should be clear and straightforward, with the intent of assuring, normalizing, validating, and empowering the individual. Overwhelming emotions can block an individual’s ability to think and cope.

- Assisting the person with describing the problem to help find his or her own solution. When people develop their own solutions, they are more likely to follow through with them and are more willing to learn and use new coping skills.

- Helping the person identify available resources, coping strategies, and sources of support. An examination of coping strategies helps the individual determine what worked and what did not in the past when dealing with stressors. With this knowledge the individual can develop new coping strategies to deal with the current and future difficulties. Providing advice or giving answers to people in crisis lowers self-esteem and fosters feelings of dependency on others to provide solutions.

- Selecting one or more specific, time-limited goals that take into consideration the person’s significant others, social network, culture, and lifestyle. Collaboratively develop a plan of action for recovery to help the person restabilize and begin moving toward the future. Assist the individual as he or she explores advantages and disadvantages of possible options. Summarize, focus, and clarify.

- Implementing the plan and evaluating its effectiveness. Adjust the plan as necessary, and if ongoing care is needed, refer the individual to appropriate community resources that can provide it.

Case Examples

Suicide

Whether a psychologist works in a college counseling center, community mental health agency, inpatient setting, or outpatient private practice or with individuals in the aftermath of a disaster, he or she is likely to see people who present with an elevated risk for suicide. The psychologist must have readily at hand the crisis intervention and emergency management tools necessary to deal with the problem of patient suicidality as well as a familiarity with state laws. Psychologists should have a clear idea of what steps they can and should take once they believe that “an attempted suicide is likely: use of crisis intervention techniques, referral to an emergency service, referral to a psychiatrist for medication, and/or civil commitment” (Stromberg et al., 1988, p. 469). It is critical for the psychologist who assesses or treats suicidal patients to know the resources that are available for emergencies and outpatient crises. Specifically, the psychologist must know community crisis intervention resources and which hospital he or she might use for voluntary or involuntary hospitalization of suicidal patients, as well as having a thorough understanding of the procedures for each setting (Pope, 1986).

Suicide can result from any development or situational crisis. Individuals who feel overwhelmed and confused, along with experiencing intense loss, anger, and grief, can view suicide as a viable alternative. There is a consensus that crisis management principally entails therapeutic activism, the delaying of the patient’s suicidal impulses, the restoring of hope, environmental intervention, and consideration of hospitalization (Fremouw, de Perczel, & Ellis, 1990).

Case Vignette

Sonya recently moved from the Midwest to a large city to start a new job. Shortly after she arrived she lost her job when her company downsized her division. A week later her apartment was burglarized. A strained relationship with her parents prevented Sonya from asking them for financial help, and returning home was not an option.As the days passed, Sonya found it increasingly difficult to concentrate, eat, get out of bed, and look for employment. She was running short of funds and realized that she would not be able to pay her rent and was facing eviction. A counselor at her church met with her and learned that Sonya viewed suicide as a way to escape an intolerable situation and that she felt hopeless about the future.

Assessment and Risk Factors

Because the suicidology literature is voluminous, diverse, and sometimes contradictory, psychologists may have difficulty determining the relative importance of various factors when assessing individuals for suicide risk. Simon (1987) stated, “there are no pathognomic predictors of suicide” (p. 259). Because each individual is unique, the nature of assessment and measurement is difficult. Motto (1991) noted that a measure or observation that may determine suicide risk in one person might have different significance or no relevance at all for another. Clinicians need an opportunity to establish a level of trust that assures candor and openness in order to be in an optimal position to assess risk (Motto, 1991). Sonya’s counselor was able to establish a relationship with her and indeed found, upon direct query, that she had experienced a series of acute stressors and in response, as she felt increasingly depressed and hopeless, developed a specific plan for committing suicide.

A complete evaluation of risk factors, including Sonya’s psychiatric diagnosis, substance abuse, previous suicide attempts, a family history of suicide, and current level of functioning, should be considered in conjunction with psychological assessment results (Bongar, 1992; Maris, Berman, Maltsberger, & Yufit, 1992). An integrated perspective on assessment and treatment of Sonya’s suicidality must be maintained (Simon, 1992). However, it should be emphasized that the assessment of Sonya’s risk for suicide should never be based on a single score, measure, or scale (Bongar, 2002).

Any suicidal crisis (ideation, threat, gesture, or actual attempt) is a true emergency situation: It must be dealt with as a life-threatening issue in clinical practice and should prompt an examination of the lethality potential of present or previous suicidal situations. Factors that substantially increase Sonya’s imminent risk include the presence of a specific plan by the patient, accessibility of lethal means, the presence of syntonic or dystonic suicidal impulses, behavior suggestive of a decision to die, and admission of wanting to die (Bongar, 2002).

Among the most serious risk factors are those of various psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and alcoholism or drug abuse (Asnis et al., 1993; Linehan, 1997, 1999; Stoelb & Chiriboga, 1998). In a comprehensive review of the literature, Tanney (1992) found that more than 90% of adults who have committed suicide were suffering from a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at the time of their death. It is clear that proper diagnosis and treatment of acute psychiatric illness can lower the risk for suicide, and it is necessary to recognize that “the most basic management principle is to understand that most suicide victims kill themselves in the midst of a psychiatric episode” (Brent, Kupfer, Bromet, & Dew, 1988, p. 365). Brent and his colleagues (Brent, Bridge, Johnson, & Connolly, 1996) noted the need to involve the family for support and improved treatment compliance.

There are a number of social clues, including Sonya’s putting her affairs in order, giving away her prized possessions, behaving in any way that is markedly different from her usual pattern of living, saying good-bye to her friends or psychotherapist, and settling her estate (Beck, 1967; Shneidman, 1985). The presence of one or more of the following psychological variables represents increased risk for completed suicide (Shneidman, 1986).

- Acute perturbation (the person is very upset or agitated).

- The availability of lethal means (e.g., purchasing or having available a gun, rope, poison, etc.).

- An increase in self-hatred or self-loathing.

- A constriction in the person’s ability to see alternatives to his or her present situation.

- The idea that death may be a way out of terrible psychological pain.

- Intense feelings of depression, helplessness, and hopelessness.

- Fantasies of death as an escape, including retrospectives, on patient’s own funeral (imagined scenes of life after death increase the risk).

- A loss of pleasure or interest in life.

- The feeling that he or she is a source of shame to his or her family or significant others, or evidence that the patient has suffered a recent humiliation.

Five specific components in the general formulation of suicide risk were identified by Maltsberger (1988):

- Assessing the patient’s past responses to stress, especially losses.

- Assessing the patient’s vulnerability to three lifethreatening affects: aloneness, self-contempt, and murderous rage.

- Determining the nature and availability of exterior sustaining resources.

- Assessing the emergence and emotional importance of death fantasies.

- Assessing the patient’s capacity for reality testing (p. 48).

The following brief inquiry developed by Motto (1989) is appropriate in settings where rapid decisions must be made (e.g., the emergency room, or consult service of a general hospital) or when a brief screening device is needed. This approach rests on the premise that “going directly to the heart of the issue is a practical and effective clinical tool, and patients and collaterals will usually provide valid information if an attitude of caring concern is communicated to them” (p. 247).

- Do you have periods of feeling low or despondent about how your life is going?

- How long do such periods last? How frequent are they? How bad do they get? Does the despondency produce crying or interfere with daily activities, sleep, concentration, or appetite?

- Do you have feelings of hopelessness, discouragement, or self-criticism? Are these feelings so intense that life doesn’t seem worthwhile?

- Do thoughts of suicide come to mind? How persistent are such thoughts? How strong have they been? Did it require much effort to resist them? Have you had any impulses to carry them out? Have you made any plans? How detailed are such plans? Have you taken any initial action (such as hoarding medications, buying a gun or rope)? Do you have lethal means in your home (e.g., firearms, pills, etc.)?

- Can you manage these feelings if they recur? If you cannot, is there a support system for you to turn to in helping to manage these feelings?

Intervention and Patient Management

It is crucial that psychologists are well trained and knowledgeable about assessing for and managing potential suicidality. When is the right time to hospitalize a patient who professes suicidal ideation? How can psychologists best manage and provide treatment to patients? An important issue is the patient’s competency and willingness to participate in management and treatment decisions (Gutheil, 1984, 1999).

The first management decision in treating a suicidal patient is to determine treatment setting, which includes consideration of characteristics of both the patient and therapist, and a careful evaluation (including a clear definition of the risks and the rationale for the decisions that one is making; Motto, 1979). For acute crisis cases of suicidality, provide a relatively short-term course of psychotherapy that is directive and crisis focused, emphasizing problem solving and skill building as core interventions.

Slaby (1998) described 13 elements in managing the outpatient care of suicidal patients.

- Conduct initial and concurrent evaluations for suicidal ideation and plans.

- Eliminate risk, by enhancing or diminishing factors that influence self-destructive behaviors.

- Determine the patient’s need for hospitalization.

- Evaluate and instigate psychopharmacotherapy to treat the underlying disorder (i.e., depression).

- Encourage increasing social support with the patient’s friends and family.

- Provide individual and family therapy.

- Address concurrent substance use.

- Refer for medical consultation, if needed.

- Referforelectroconvulsivetherapy(ECT),ifappropriate.

- Use psychoeducation with patient and significant others to manage and treat suicidality.

- Arrange for emergency coverage for evenings and weekends.

- Help patient and significant others set realistic goals for management and treatment of suicidal behaviors.

- Keep current, accurate records.

It is important to note that although these treatment guidelines will enhance patient care, implementation of some or all of these elements does not insure that a patient will not commit suicide.

Some people will kill themselves because of abrupt changes in clinical status. Others may lie to their therapist to avoid interference with their plan. Most who die, however, will show signs of a deteriorating condition and will confirm in words that they require more intensive treatment (Slaby, 1998, pp. 37–38).

The psychologist must not hesitate to contact others in the life of the patient and enlist their support in the treatment plan (Slaby, Lieb, & Trancredi, 1986). Litman (1982) recommended that if a therapist treats a high-risk outpatient who thinks he or she can function as an outpatient, it is the therapist’s responsibility to ensure that the risk is made known to all concerned parties (i.e., the family and significant others).

Seek professional consultation, supervision, and support for difficult cases. Consultation may be either formal (involving written documentation and possibly payment) or informal and may take place with a senior colleague, an expert in the area of concern, a peer, or a group of peers. Additionally, one may wish to consult with an individual outside of one’s own professional domain, such as an attorney or physician; this is referred to as interprofessional consultation (Appelbaum & Gutheil, 1991; Bongar, 2002).

Natural Disasters and Acts of Terrorism

Disasters often occur with unexpected swiftness and overwhelming force, adversely affecting ordinary people who were in “the wrong place at the wrong time” (Charney & Pearlman, 1998). Natural disasters, man-made disasters, and acts of terrorism shatter the assumptions of control, personal safety, and the predictability of life.When a cataclysmic event occurs, the function of the community is disrupted, causing a breach in the individual’s emotional and physical support system. Worksites and homes may have been destroyed, people may be injured or dead, and lives are irrevocably altered. The impact of the traumacoupled with thefear that the event could recur fuels our deepest fears and impacts the lives of all within the community.

Case Vignette

In late August, the community of St. Petersburg was hit by a devastating hurricane that destroyed homes and property. Flooding damaged John’s home, and he moved to temporary housing provided by the American Red Cross. When offered crisis intervention services John declined, stating that others were in greater need. Upon further discussion, the therapist learned that John felt he should be able to provide for himself and viewed outsid eassistance as a sign of weakness and failure on his part.

Assessment and Intervention

In the aftermath of this disaster, John may be experiencing a sense of unreality and dissociation, although the hurricane is over and the disaster site is calm. Basic needs, such as water, food, and a safe place, are the initial focus following a disaster because “physical care is psychological care, and this is the prime and essential function of relief organizations” (Kinston & Rosser, 1974). It is frustrating when victims of disaster refuse services. Psychologists faced with this dilemma should be empathetic and strive to normalize the person’s reaction to the disaster during the initial interview. John’s cultural norms should be considered when one assesses for acute and long-term problems, and at the same time one should promote positive coping strategies.

It should be determined if John would be amenable to receiving support and treatment from another local community, cultural, or religious organization engaged in providing relief care. Disaster victims rarely present to traditional mental health services (Lindy, Grace, & Green, 1981). However, most individuals who experience a disaster will do well and will not develop PTSD. The development of psychological sequelae depends on the nature of the disaster, the type of injuries sustained, the level of life threat, and the period of community disruption.

The Four Phases of Disaster Response

Four phases have been identified that describe how people response to disaster (Cohen, Culp, & Genser, 1987). When natural disasters or acts of terrorism result in death, and the news media besieges the community, the people affected may feel overwhelmed and experience a range of reactions including shame, hatred, and guilt (Shneidman, 1981). It is normal during the first phase for people to experience feelings of disbelief, numbness, intense emotions, fear, dissociation, and confusion in immediate reaction to a disaster. People may appear apathetic and dazed, unable to grasp the reality and impact of the event.

It is during the second phase, in the days and months following a disaster, that aid from organizations and agencies outside the area assist the community with cleanup and rebuilding.At this time many individuals may experience denial and intrusive symptoms that are accompanied by autonomic arousal (e.g., a heightened startle response, insomnia, hypervigilance, and nightmares). As people start to realize the reality of the loss, common affects that may be evident include apathy, withdrawal, guilt, anger, anxiety, and irritability.

The third phase may last up to a year and marks a time when individuals typically shift their focus from the survival of the group or community back to the fulfillment of their individual needs. Individuals may feel disappointment and resentment when hopes of restoration and expectations of aid are not realized. Reconstruction, the final phase, can last for years as survivors gradually rebuild their lives and establish new goals and life patterns. Recovery from disaster involves the resolution of psychological and physiological symptoms through reappraising the incident, ascribing meaning, and integrating new self-concept (Cohen et al., 1987).

Green (1990) explicated the mediating characteristics of disasters. He noted that the greater the person’s perceived threat of death or injury, the more likely the potential for adverse psychological functioning. Injury and physical harm, exposure to dead and mutilated bodies, and the violent, sudden death of a friend, co-worker, or loved one can cause traumatic stress. It is not necessary to witness such an event to experience intrusive thoughts and stress. For example, news broadcasts that replayed the horrific events of the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, that killed thousands of people when a highjacked jet airliner crashed in Pennsylvania and the World Trade Towers and when a portion of the Pentagon Building burned and collapsed after being attacked by terrorists manning hijacked commercial airplanes created considerable distress for most viewers. Research needs to be conducted to elucidate the impact the news media has in creating collective traumatic stress many miles away from the catastrophic event. Intentional death and harm, resulting from man-made disasters and terrorist attacks, is viewed as particularly heinous and incites strong emotions.

Following a disaster, rapid response teams must mobilize rapidly, often with little warning. A multidisciplinary team that includes psychologists, physicians, social workers, nurses, and other mental health paraprofessionals is an ideal way to quickly identify high-risk groups and behaviors, to promote recovery from acute stress, and to decrease the likelihood of long-term adverse effects. Teams that arrive from outside the geographic area often benefit from working collaboratively with local community members who can assist them with integrating into the disaster environment. Psychologists should possess basic knowledge of the culture and norms of the group they are trying to assist. School systems, workplaces, communities, and foreign nations all have their unique customs and culture.

Debriefing the Members of the Crisis Response Team

Members of rapid response teams providing crisis intervention are not immune to the stressors of the disaster and of caring for the victims. Rescue workers, heroes, people who are injured in the event, and children are at increased risk for stress-related sequelae. Crisis workers often experience the symptoms of PTSD, ASD, depression, and anxiety (Durham, McCammon, & Allison, 1985; Fullerton, McCarroll, Ursano, & Wright, 1992). Vicarious traumatization results when the crisis worker is adversely affected by the trauma that is manifested by the individuals in crisis.

Although debriefing is valuable in helping crisis workers “regain a state of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral equilibrium” (James & Gilliland, 2001), it is not recommended that debriefing be employed as an intervention for distressed crisis workers during or at an early stage of disaster response, because it is intended to “facilitate psychological closure to a traumatic event” (Everly & Mitchell, 1999; Shalev, 1994). Debriefing is a group intervention in which team members are guided through a chronological reconstruction of the disaster. The objective is to gain an understanding of the events related to and surrounding the disaster before the trauma becomes concretized, but it can only be effective if individuals are able to listen, express feelings, and cognitively restructure the experience.

James and Gilliland (2001) compiled a list of six precautions from a review of the literature that should be considered when providing crisis intervention and during the debriefing process:

- Crisis work should be done in teams.

- Time for sleep and to decompress is critical.

- Crisis team members should not debrief each other.

- Debriefing should take place away from the site of the disaster.

- The structure of the organization and the way in which it provides disaster relief services affect how the team copes at the disaster site.

- Excellent physical and mental health is required to conduct crisis work.

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing and Critical Incident Stress Management

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) was developed by Jeffery Mitchell in response to his reactions to traumatic incidents he witnessed as a firefighter and paramedic. It was originally formalized to be used with emergency workers but is now used with a wide range of individuals who have experienced trauma, including crisis workers, primary victims, and secondary observers (Everly & Mitchell, 1999). Critical Incident Stress Debriefing is used to mitigate acute stress that results from traumatization, to help crisis workers attain precrisis equilibrium and homeostasis, and to identify individuals who require additional mental health care (Everly & Mitchell, 1999).

Formal CISD is conducted approximately 24 hours after the event by a trained and certified CISD mental health professional. It was not designed as a substitute for psychotherapy or individual debriefing or as a stand-alone intervention (Everly & Mitchell, 2000). The “seven-phase group crisis intervention process” lasts approximately two to three hours and follows a prescribed format that consists of seven segments: (a) introduction, (b) fact finding, (c) thoughts, (d) reaction, (e) symptoms, (f) teaching, and (g) reentry (Everly & Mitchell, 1999).

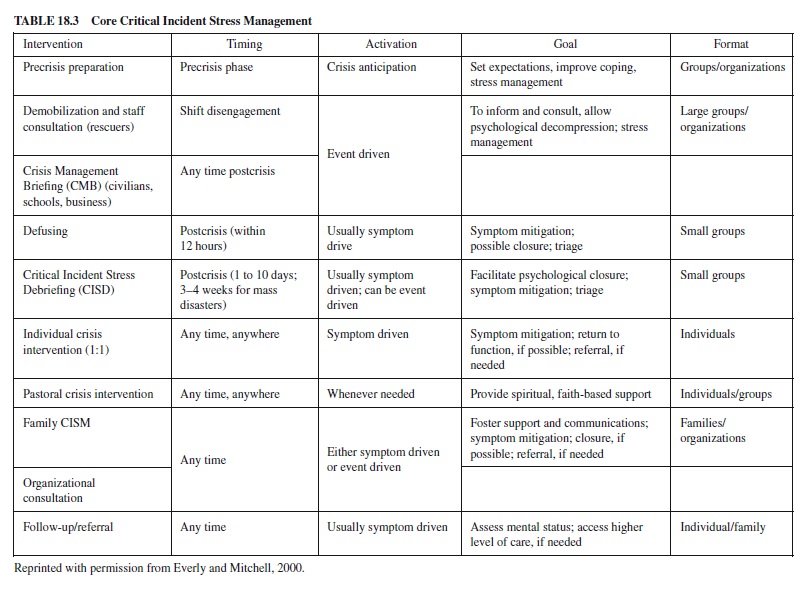

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing is a component of Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM). Critical Incident Stress Management is a term that describes an integrated and comprehensive collection of “crisis response technologies for both individuals and groups” (Everly & Mitchell, 1999).

The purpose of CISM interventions is to reduce the impairment from traumatic stress and to facilitate needed assessment and treatment. The core eight CISM components are summarized in Table 18.3.

Illness

Although illness is a common occurrence for many older adults, the advent of a chronic or terminal illness is life altering and places permanent restrictions on the individual’s life. For example, adjustment to bodily changes resulting from surgery or illness, altered expectations of the future, environmental restrictions such as a lack of physical mobility or confinement to a wheelchair, and changed relationships with significant others are typically experienced as losses. One or any combination of these illness-related losses constitutes a serious threat to an individual’s sense of body integrity, which in turn compounds the stresses related to treatment and invasive medical procedures.

Case Vignette

Mary was a 78-year-old retired teacher who lived alone in her home in a suburb of Chicago. Her daughter noticed that she was forgetting to bring in the newspaper and that she was no longer tending her garden, a long-standing source of enjoyment and pride. She was having problems finding her keys and remembering to turn the stove off when she was done cooking. Mary’s daughter had her evaluated by a neuropsychologist and it was determined that she was experiencing the early stages of Alzheimer’s dementia.

Assessment and Intervention

The news that a loved one has a progressive, terminal illness likeAlzheimer’s disease is frightening and difficult to accept. Although new medications, such as Aricept, and some herbal supplements like vitamin E and ginkgo may slow the dementing process, at this time there is no cure. It is important for psychologists to have an understanding of not only the shortand long-term cognitive, emotional, and eventual physical changes, but also an appreciation of the ramifications of the disease process on the caregiving spouse and family members.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Approximately 4 million Americans are afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease and this number is expected to grow to 14 million by the year 2050. Notably, an estimated 2.7 million spouses and family members provide care for a family member with the disease. On average, most individuals survive for 8 to 10 years after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and will spend five of those years closely supervised by family or living in a skilled nursing home facility (Hendrie, 1998). The chronic, debilitating aspects of the disease are stressful for caregivers.

As the years pass and the disease progresses, the coping mechanisms of the caregiver may breakdown. The symptoms during the early stages of the disease, typically lasting 2 to 4 years, are progressive confusion and forgetfulness. The symptoms occurring during the middle stage, lasting approximately 2 to 10 years, include increased confusion and memory loss, decreased attention span, and difficulty recognizing family and close friends. The symptoms during the final stage, roughly 1 to 3 years, include diminished ability to communicate, impaired swallowing, weight loss, and inability to recognize self or family members. Mary and her daughter need empathy, support, and education regarding the disease process and community resources. Many caregivers will seek out or be referred to crisis intervention services.

Five Stages of Death and Dying

The initial reactions of Mary and her mother may be similar to those described as the five stages of death and dying (KüblerRoss,1969).Thefivestages consistof(a)denialandisolation, (b) anger, (c) bargaining, (d) depression, and (e) acceptance. Individuals do not necessarily progress through each stage, nor do they experience the stages in a linear, sequential order. Some people may experience a stage more than once, whereas othersmaybeunabletoprogressbeyondagivenstage.Awareness of these stages may be of value to the clinician working with a patient or a caregiver in crisis. Both Mary and her daughter will grieve and mourn in response to the losses that result from Alzheimer’s disease. As with any crisis situation, psychologists need to provide treatment or make referrals to appropriate health care clinicians, if normal grieving evolves into major depression.

Elder Abuse

A review of the literature shows that Alzheimer’s caregivers are at increased risk for depression, elder abuse, illness, burnout, and social isolation (Dippel, 1996). All caregivers have normal life stressors to deal with, but if the stress of caring for a cognitively impaired loved one becomes intolerable, it can sometimes result in abuse. Psychologists should be aware of local laws regarding elder abuse. A multidisciplinary approach that includes psychologists, physicians, and social workers can be useful when treating the abused victim. In many instances, both the victim and the caregiver should receive social services. The attainment of new, adaptive coping skills and, in some instances, breaking the cycle of abuse is the focus of the intervention for the caregiver. It is important to remember that in cases of physical abuse, some suggest that the cycle of violence theory holds, in that the abusive children of the elderly parents were abused by them when they were children. They then act out their anger on the dependent elder parent because the use of violence has become a normal way to resolve conflict in their family. The crisis worker must help the adult child caregiver address his or her own past history of child abuse to stop the cycle (Kanel, 1999, p. 204).

Caring for the Caregiver

It is beneficial for the caregiver, as well as the patient, to have regularly scheduled respite care. This may entail the use of a community day care program, a volunteer respite companion, or home health service. Frustration, burnout, and social isolation can adversely affect the functioning of the caregiver. Although Mary’s daughter may feel guilty about leaving her mother, regular breaks will help her maintain her well-being.

Acaregiver’s psychoeducation and support group not only provides support but is also an invaluable source of information regarding community resources. It can be overwhelming for a caregiver to deal with numerous medical specialists, community agencies, insurance forms, and more. Caregivers may benefit from working with a caseworker or healthcare specialists who can provide training to manage cognitive changes (e.g., use of a memory book) and ensure safety (e.g., with alarms or locks on doors).

Psychologists who work with caregivers can encourage them to utilize the ten steps to enhance caregivers’ coping that were compiled from national experts by Castleman, Gallagher-Thompson, and Naythons (1999). These are the recommendations for caregivers:

- Be confident of the diagnosis (seek a second opinion).

- Be realistic (become educated about the disease process and know your options).

- Enjoy any pleasant surprises (some personality changes resulting from Alzheimer’s disease may be positive).

- Treat everything (other medical and psychiatric conditions should be appropriately treated).

- Combine medication with psychological and complementary therapies (consider attending a support group, exercising, or engaging in therapy).

- Assemble an extensive support network (ask other family members, friends, and neighbors for help when needed).

- Take good care of yourself (physically, emotionally, and socially).

- Take good care of the person with Alzheimer’s.

- Plan for the future early (make legal, financial, and medical decisions during the early stages of the disease).

- Stay informed (keep updated about new medications and treatments).

Cultural Considerations

An additional pressure in providing effective services has been the diversification of our society, especially in urban settings. The projection for the year 2050 is that many urban settings will be predominately populated by people whose heritages are from Latin and Central America, Asia, and Africa (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1996). The person taking the initial crisis call must be able to correctly evaluate the emergent nature of the problem; this is particularly difficult when he or she is not familiar with the background (not to mention the language) of the caller. Familiarity with diverse cultural norms is relevant here: What is considered a crisis in one cultural group might not be a crisis in another group. Responses that will be considered helpful may also vary according to cultural or ethnic group practices.

In cultural groups whose orientation is more toward an interdependent focus (the needs of the group are more important than the individual), family members tend to delay seeking help until the family can no longer cope with the problem (Tracey, Leong, & Glidden 1986;Triandis, Kashima, Shimada, & Villereal, 1986). Cultural considerations at the individual level can be determined by using a modification of the Systematic Treatment Selection approach to consider patient characteristics, relationship variables, treatment selection, and the cultural variable that affect decision making (Shiang, Kjellander, Huang, & Bogumill, 1998).

Some general guidelines can be suggested for crisis situations:

- Become familiar with case studies of representative local cultural groups.

- Seek consultation with people who have detailed knowledge of the cultural norms and their psychiatric manifestations.

- Ask the person or other people in the person’s environment about the level of abnormality or normality of this behavior.

- Ask about consequences for endorsing abnormal

- Apply Western-based categories of illness only after the culture-specific categories have been reviewed and considered nonapplicable.

- At all stages of a crisis, consider the cultural meanings of the psychosocial impact, the type of plan developed to resolve the immediate crisis, the ways of implementing the plan, and the types of follow-up to the implementation.

In the section related to mobile crisis units we present a brief case study to highlight the cultural considerations in the context of a crisis with an elderly client.

Collaborations Within the Mental Health Field

Hospital settings have traditionally provided services using a multidisciplinary team approach. In a crisis situation it has been found that this type of teamwork is critical; not all the needs of a person in crisis can be effectively handled by a person trained in one approach. Further, once the team operates in the environment of the person in crisis, general rules of hierarchy and authority necessarily become of secondary importance to the need to help the person resolve the “problem.” Thus, distinctions between the disciplines are less clearly drawn. For example, consult-liaison teams that link to crisis teams and primary care facilities can provide assessment, diagnosis, and knowledge about where the client can best be treated in their particular system. Once the crisis has been resolved, follow-up with the multidisciplinary team can cast a wider net to provide services that help prevent relapse (Shiang & Bongar, 1995).

Collaborations Across Agencies: Mobile Crisis Intervention Teams

One program that exemplifies the collaboration between multiple agencies is the use of mobile crisis units, which are community-based entities that dispatch professionals to a scene in the field to provide outreach and treatment (Ligon, 2000). The intent of these units is to address the “problem” using both law enforcement capabilities and mental health services to assess and “talk down” a crisis, to evaluate for restraint (via hospitalization or jail), and to ensure the safety of the community. An additional objective was to reduce the amount of resources and funding needed by using the most effective and efficient means of intervention possible (i.e., save money by allowing first-response police officers to return to duty more quickly, reduce admissions to hospitals, and provide repeat visits for volatile ongoing situations).

As of 1995, at least 39 states had some mobile capacity, and almost all of these states were sending teams to sites such as homes, hospital emergency rooms, residential programs, and shelters (Geller, Fisher, & McDermeit, 1995). In comparison to use of the emergency room, these mobile crisis units generally provided (a) greater accessibility of services to an indigent population, (b) more accurate assessments by observing more of the patient’s environment and functioning in the real world, (c) earlier interventions in the phase of decompensation to help prevent hospitalization, and (d) superior liaisons with other agencies to facilitate referrals for the patient. In addition, the mobile crisis intervention teams identified strengths and weaknesses in past training and were able to offer intensive further training and public education (Zealberg, Santos, & Fisher, 1993).

A national survey found that most states believed mobile crisis units had helped to reduce hospital admissions. However, there has been little formal evaluation of their effectiveness. Geller et al. (1995) cautioned that the beliefs about the benefits of mobile crisis units tend to outnumber the facts.The authors suggest that, in the past, the use of descriptive reports to encourage further funding was misleading; few states regularly evaluated the effectiveness of their programs.