Sample Child Psychotherapy Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Interest in the conduct and effectiveness of child and adolescent psychotherapy is a relatively recent event in the mental health treatment literature (e.g., Kazdin, Siegel & Bass, 1992; Kendall & Morris, 1991; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c). Unlike the adult psychotherapy literature and related writings, which can be traced back to ancient times, the child and adolescent psychotherapy literature can be traced with any certainty only to the early twentieth century (e.g., Kanner, 1948; Kratochwill & Morris, 1993; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998b). The one notable exception involves research on those children who have been diagnosed as having a developmental disability such as mental retardation or autism. For these children, the child treatment literature can be traced to the work of Jean Itard in France and his attempts in the early 1790s to educate the “Wild Boy of Aveyron” (Itard, 1962; Morris, 1985).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The developments in the early twentieth century that contributed substantially to our present-day emphasis on child and adolescent psychotherapy were the following: (a) the mental hygiene/mental health movement in the early to mid1900s, as well as the early-1900s advocacy work of Clifford Beers (1908), which focused on improving psychiatric services for people having emotional problems; (b) the introduction of dynamic psychiatry and Sigmund Freud’s (1909) detailed case of “Little Hans,” as well as the psychoanalytic play therapy work in the 1920s and 1930s of Melanie Klein and Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, and Anna Freud’s edited book series (with Heinz Hartmann & Ernst Kris) beginning in 1945, The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child; (c) the intelligence testing movement begun by Alfred Binet in France in the early 1900s; (d) the establishment of child welfare professional associations in the 1920s (e.g., the Council for Exceptional Children and the American Orthopsychiatry Association), as well as the formation at a much earlier time of the Association of Medical Officers of American Institutions for Idiots and Feebleminded (circa 1876; currently named the American Association on Mental Retardation); (e) individualized instruction and special education classes for mentally and emotionally disabled students, with the first teacher-training programs established for the latter students in the early 1910s in Michigan; and (f) the establishment of child guidance clinics throughout the United States in the early to mid-1900s (e.g., Kanner, 1948; Kauffman, 1981; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998b).

Other developments influencing our present day psychotherapy approaches with children and adolescents were quite different from the psychoanalytic emphases of Sigmund and Anna Freud and Melanie Klein. One development dates back almost as far as Freud’s psychoanalysis but has its origins in the experimental psychology laboratory. This therapy approach became known as behavior therapy or behavior modification and was based on psychological theories of learning and conditioning (see, e.g., Bandura, 1969; Bandura & Waters, 1963; Hull, 1943; Mowrer, 1960; Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1938, 1953; Thorndike, 1913, 1931).

Two studies involving behavioral approaches gained early recognition for their attempts to understand and treat children’s behavior disorders and each, like Freud’s Little Hans case study, focused on children’s fears. The first case study was by Watson and Raynor (1920), who investigated the development of fear in an 11-month-old boy named Little Albert; the second case study, by Jones (1924), involved the treatment of a fear in a 3-year-old boy named Peter.

A second nonpsychoanalytic development that impacted our present day approaches to child and adolescent therapy took place in the early 1940s. This new development was advocated by such writers as Frederick Allen (1942) and Virginia Axline (1947) and incorporated the psychoanalytic emphasis on the therapeutic relationship but deemphasized Freud’s conceptualization of the unconscious and its role in explaining children’s verbalizations and related play activities. In addition, unlike Freudian approaches, these writers emphasized the child’s or adolescent’s present life reality instead of his or her past experiences as the central focus of therapy. The emphasis, therefore, of these relationship therapy approaches was on providing the child with a warm, accepting, and permissive therapeutic environment in which few limitations were placed on him or her. By providing these “necessary” relationship and environmental conditions within the therapeutic setting, Allen, Axline, and others believed that the child or adolescent client would be provided with the opportunity to reach his or her highest level of psychological growth and mental health. Axline’s writings followed the client-centered approach of Carl Rogers (1942), and Allen’s therapeutic procedures were more consistent with an ecological perspective and the emerging area of social psychiatry.

In this research paper we present an overview of four major therapeutic approaches that are currently discussed in the child and adolescent psychotherapy literature (see, e.g., D’Amato & Rothlisberg, 1997; Kratochwill & Morris, 1993; Mash & Barkley, 1989; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c). These therapies are behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, child psychoanalysis, Adlerian therapy, and client-centered (humanistic) therapy. Before these therapies can be discussed in any detail, however, certain issues need to be discussed regarding the conduct of child and adolescent psychotherapy.

Issues Related to the Conduct of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy

Although early work by Levitt (1957, 1963) suggested that children and adolescents receiving “traditional” forms of psychotherapy did not improve appreciably more than those who did not receive treatment (i.e., approximately 66% of the treated children and 73% of the untreated children were rated as “improved”), a later meta-analysis by Casey and Berman (1985) indicated that there was a significant effect size for “treatment” (behavior therapy, psychodynamic therapy, or client-centered therapy) when compared to the control condition. Casey and Berman also reported that for certain types of outcome measures the behavior therapies were found to be better than the nonbehavioral therapies, but when the type of measure was controlled for, no differences were found in the effectiveness of the various psychotherapies. Weisz, Weiss, Alicke, and Klotz (1987), and Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, and Morton (1995), on the other hand, found in their respective meta-analyses that the average outcome for those children receiving a form of behavior therapy was appreciably better than was that for children receiving a nonbehavior therapy—with no particular behavior therapy procedure being better than any other behavioral procedure. Findings like these led Kazdin (1990) to conclude that “psychotherapy appears to be more effective than no treatment” and that “treatment differences, when evident, tend to favor behavioral rather than nonbehavioral techniques” (p. 28). Kazdin indicated that these meta-analytic studies highlighted the fact that the number of studies utilizing behavioral and cognitively based therapies outnumbered to a large extent those child and adolescent therapy studies, which incorporated such procedures as psychodynamic and client-centered approaches.

Research findings such as those from meta-analytic treatment outcome studies, as well as those involving the direct surveying of clinicians regarding treatment effectiveness (e.g., Kazdin, Siegel, & Bass, 1992), have led some writers to suggest—as has been discussed for more than 35 years in the adult psychotherapy literature (see, e.g., Beutler, 1997; Goldstein, Heller, & Sechrest, 1966; Huppert et al., 2001; Kazdin, 1997; Paul, 1967)—that we can no longer answer the question, “Is child or adolescent psychotherapy effective?” Instead, we need to answer the question, “Is this particular type of child or adolescent therapy effective for this type of child or adolescent, having this presenting problem, from this family structure and background experiences, with this type of therapist, from this type of background, with therapy being applied under these environmental conditions or constraints?” (see, e.g., Kazdin, 1990; Kendall & Morris, 1991; Morris & Morris, 2000). It is interesting to realize that a similar set of prescriptive questions in child psychotherapy was posed more than 40 years ago by Heinicke and Goldman (1960) but resulted in little or no subsequent therapy outcome research. Specifically, Heinicke and Goldman stated, “The question is no longer: Does therapy have an effect?—but rather: What changes can we observe in a certain kind of child or family which can be attributed to involvement in a certain kind of therapeutic interaction? Within this very broad question, we can vary the nature of the child’s problem, the [therapeutic] orientation of the therapist, the frequency of the therapeutic contact, the length of the contact, the degree of involvement of parents, etc.” (p. 492).

The success of child and adolescent therapies may also be influenced by comorbidity factors. For example, will children having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) improve equally using the same therapy procedure whether or not they have a comorbid diagnosis of conduct disorder? Or will adolescents having a diagnosis of agoraphobia with panic attacks improve as rapidly when receiving the same therapy method independent of the presence or absence of a comorbid diagnosis of dysthymia? Or will young adolescents who have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) improve equally well with the same method of psychotherapy as will those young adolescents who have OCD and school refusal? Because few, if any, therapy outcome research studies exist that address these types of comorbidity questions (see, e.g., Kendall, Brady, & Verduin, 2001), no definitive answers can be given at this time. Although our current state of knowledge of child and adolescent psychotherapy procedures has not yet progressed to the point where specific prescriptive questions such as those listed can be answered at this time, there have nevertheless been some attempts in the literature to address more general prescriptive questions (see, e.g., Barkley, 1990; Bear, Minke, & Thomas, 1997; Kavale, Forness, & Walker, 1999; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c).

The conduct of child or adolescent therapy is complicated also by the fact that it is not always clear who is the client (Kendall & Morris, 1991). Unlike psychotherapy with adults, the child or adolescent is not typically the person who initiates contact and an appointment with the clinician. Moreover, the child or adolescent may not be the only person who enters the therapist’s office for the first visit, and it is rare that the child or adolescent pays for the therapy services. In most cases, the child’s or adolescent’s parent or guardian, teacher or other school personnel, or a representative of the juvenile justice system brings the “client” to the therapist’s office, and it is one of these people (or, possible, an agency representative) who will probably pay for the therapist’s services. In addition, unlike in adult psychotherapy, it is likely that one of these latter persons will have the legal right to review the therapist’s session notes or request a report on the child’s or adolescent’s progress in therapy, therefore impacting the confidentiality between therapist and client (Arambulla, DeKraai, & Sales, 1993; DeKraai, Sales, & Hall, 1998). In addition, parents and teachers may believe that the client is the child or adolescent and may thus become somewhat concerned later in the therapy process if they are asked to become integrally involved in the treatment plan that is developed. Therefore, defining “who is the client” early in the treatment program is important not only to reduce confusion on the part of the various participants but also to establish limits to confidentiality and establish who, other than the therapist, will be participating in the child’s or adolescent’s treatment plan. These types of decisions regarding who is the client and what the therapy process entails should only be made following a thorough intake assessment. Each person included in the therapy process should then give his or her consent to participate and specify the conditions (within the legal constraints imposed by state and federal laws) under which the therapist will be able to share each participating client’s comments with the other participants and the therapist will be able to share his or her own perspective with the participating persons (Arambulla et al., 1993).

In terms of the therapeutic relationship, research in this area still lags far behind the adult literature even though several child therapy practices (e.g., child psychoanalytic therapy and client-centered therapy) indicate that the therapeutic relationship is at least a necessary condition for effecting positive behavior change. Kendall and Morris (1991) and Morris and Nicholson (1993) noted that although such “therapist variables” as therapist warmth, therapist empathy, model similarity, therapist ethnicity, and therapist verbal encouragement and physical contact have been discussed in the literature, as have such “client variables” as type of presenting problem, pretreatment level of prosocial functioning, and level of motivation, no firm conclusions can be made at this time regarding the contribution of these factors to therapy outcome. Moreover, a child’s or adolescent’s knowledge of the absence (or limited nature) of confidentiality in psychotherapy, although not yet studied, may influence therapy outcome as well as the individual’s level of self-disclosure during therapy (Kendall & Morris, 1991).

The personal beliefs and related values of the therapist may also impact treatment outcome. The notion of therapist values is not only related, for example, to such areas as the cultural or ethnic values of the therapist vis-à-vis the client (and the client’s family) or to the religious beliefs of the therapist versus those of the client (and his or her family), but also to situations in which the clinician sees the following individuals in psychotherapy: (a) gay or lesbian adolescents who do not construe their current psychological difficulties as related to their sexual preference, (b) a child or adolescent who has tested positive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), (c) a child or adolescent who is living with drug-addicted parents, and (d) a physically or sexually abused child or adolescent who has been placed by the court back into the home where the perpetrator lives (Morris & Nicholson, 1993).l

Little (or no) systematic research has been conducted on the contribution of these different factors on the outcome of child or adolescent psychotherapy or, for that matter, on the contribution of therapeutic relationship factors to therapy outcome. Instead, the literature has focused primarily on treatment effectiveness studies (i.e., empirically supported treatments) involving particular child or adolescent behavior disorders, school- or parent-based treatments, and community based treatments (see, e.g., Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c; Morris & Morris, 2000). Within the structure of these studies, researchers have adopted the unspecified, undefined, and untested working assumption that therapy should be conducted within the framework of a sound therapeutic relationship between the therapist and adolescent client (e.g., Kendall & Morris, 1991; Morris & Morris, 2000). Consistent with this assumption, the therapies described next also presume the presence of a sound therapeutic relationship between the client and therapist.

Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Methods

Behavior Therapy and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches have their roots in the learning theory positions of Ivan Pavlov (1927), B. F. Skinner (1938, 1953), Clark Hull (1943), O. Hobart Mowrer (1960), and Albert Bandura (1969, 1977; Bandura & Walters, 1963). These researchers’ respective theories of learning were tested and refined in experimental psychology laboratories during the previous century. The research findings from these theories demonstrated that people and animals behave in predictable ways and suggested that there are principles that can explain the manner in which people and animals behave. Researchers also found that intervention procedures based on these theories of learning could be developed to change people’s behaviors (Morris, 1985). This largely laboratory-based research led, beginning in the 1960s, to the application of this knowledge to more practical or clinical areas such as behavior problems and behavior disorders in children and adolescents (see, e.g., Bandura, 1969; Gardner, 1971; Graziano, 1971; Lovass & Bucher, 1974; O’Leary & O’Leary, 1972). The findings from this more clinically oriented research were encouraging and led investigators and clinicians to expand their behaviorally oriented treatment approaches to children and adolescents having a variety of behavioral difficulties.

Behaviorally oriented treatment approaches follow a general set of working assumptions (see, e.g., Kazdin, 1980; Morris, 1976; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b; Rimm & Masters, 1979). First, it is assumed that children’s and adolescents’ behavior problems are learned unless there is genetic or biological evidence to the contrary. Second, behavior problems are learned separately from (and independently of) other behavior problems or related maladaptive behaviors that the child or adolescent may manifest, unless there is genetic or biological evidence or other objective data showing that a given set of behaviors are interconnected or occur together. Third, behavior problems are setting or situation specific. This suggests that unless there is contradictory evidence, it is assumed that a child’s or adolescent’s behavior problems that are observed in one setting will not generalize to other settings or situations.This is an important assumption within the behavioral view because it forces the clinician to look within the environmental setting where the behavior problem occurred for possible reasons that contributed to the performance of the behavior. It also encourages the clinician to look into those settings where the behavior problem has not occurred to determine what factors in these settings might be preventing the behavior problem from being performed.

The fourth assumption refers to the position that the emphasis of therapy is on the here and now. This assumption directs the clinician to focus on what is presently contributing to the child’s behavior disorder or maladaptive behavior and to identify what in the child’s present environment could be modified that might effect a positive behavior change in the child. The past history of the child, therefore, is important only to assist the clinician in determining (a) which intervention approaches have been effective or ineffective in the past (settings similar to the current setting) in changing the child’s behavioral difficulties; (b) whether the frequency, severity, or duration of the behavior problem has gotten better or worse over time; and (c) whether a pattern has developed over time of the type of settings in which the behavior occurs on a regular basis (Morris & Morris, 1997). Behaviorally oriented therapists do not deny that historical events have, in some way, contributed to the development of the present behavior that the child is demonstrating; however, they maintain that because such events took place in the past, they cannot presently be manipulated unless the same causal (or maintaining) factors are still contributing to the child’s behavioral difficulties. Historical causal events are therefore of low importance in the formulation of a treatment plan and in the conduct of behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy unless such events are presently contributing to the child’s problem.

The fifth assumption indicates that the goals of behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are specific. Because behaviorally oriented therapists maintain that children’s and adolescents’ behavior problems are learned in particular settings and are specific to those situations, it follows that the goals of therapy are specific—for example, the reduction of a targeted behavior within a particular setting. Sixth, consistent with the previous assumptions, unconscious factors play no essential role in the development, maintenance, or treatment of children’s and adolescents behavior disorders. Moreover, insight is not necessary for changing a child’s or adolescent’s behavior problems. Because behaviorally oriented therapists do not accept the belief that there are underlying unconscious factors responsible for a child’s or adolescent’s behavior disorders, it follows that they do not maintain that insight is a necessary condition for effecting positive behavior change.

These latter assumptions represent a somewhat idealized position regarding the conduct of behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. In actual practice, behaviorally oriented therapists may agree with all or only some of these assumptions.

The essential difference between behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy methods is the emphasis on the contribution of cognitive processes or private events as mediators in the child’s or adolescent’s behavior change. Specifically, in cognitive-behavioral therapy, the child’s or adolescent’s thoughts, feelings, attributions, self-statements, and other cognitive variables are viewed as important factors in effecting positive behavior change (e.g., Ellis & Wilde, 2002; McReynolds, Morris, & Kratochwill, 1988; Meichenbaum, 1977; Ramirez, Kratochwill, & Morris, 1987). In contrast, behavior therapy approaches typically focus on those directly observable variables within the child’s or adolescent’s immediate environmental setting that may be modified to effect positive behavior change. This behaviorally oriented approach is more consistent with the “applied behavior analysis” model of learning of B. F. Skinner (1938, 1953), whereas the cognitive-behavioral therapy approach is more consistent with Bandura’s “social learning theory” (e.g., Bandura, 1969; Bandura & Walters, 1963), Ellis’s “rational-emotive therapy” (e.g., Ellis, 1962; Ellis & Wilde, 2002), and Beck’s “cognitive therapy” (e.g., Beck, 1976), as well as the writings of Meichenbaum (e.g., 1977), Karoly and Kanfer (1982), Mahoney (1974), and Kendall (1991, 1994). Each behavioral approach, however, shares the position that children’s and adolescents’ behavior problems are learned, are maintained by their consequences, and can be modified using procedures based on theories of learning.

The psychotherapy approaches most often used in behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy with children and adolescents involve the use of such contingency management procedures as reinforcement methods (including shaping, token economy program, schedules of reinforcement, self-reinforcement, contingency contracting, differential reinforcement of other behaviors, and differential reinforcement of incompatible behaviors), extinction, stimulus control, and time-out from reinforcement (see, e.g., Kazdin, 2000; Mash & Barkley, 1989; Mash & Terdall, 1997; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c; Sulzer-Azaroff & Meyer, 1991). In addition, modeling methods are used (e.g., Bandura, 1969, 1977), as are relaxation training and systematic desensitization procedures (e.g., King, Hamilton, & Ollendick, 1988; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b, 1998c; Wolpe & Lazarus, 1966), and self-control and self-instructional training (see, e.g., Bernard & Joyce, 1993; Hughes, 1988; Kendall, 1991, 1992; Kendall & Braswell, 1985; Meichenbaum & Goodman, 1971).

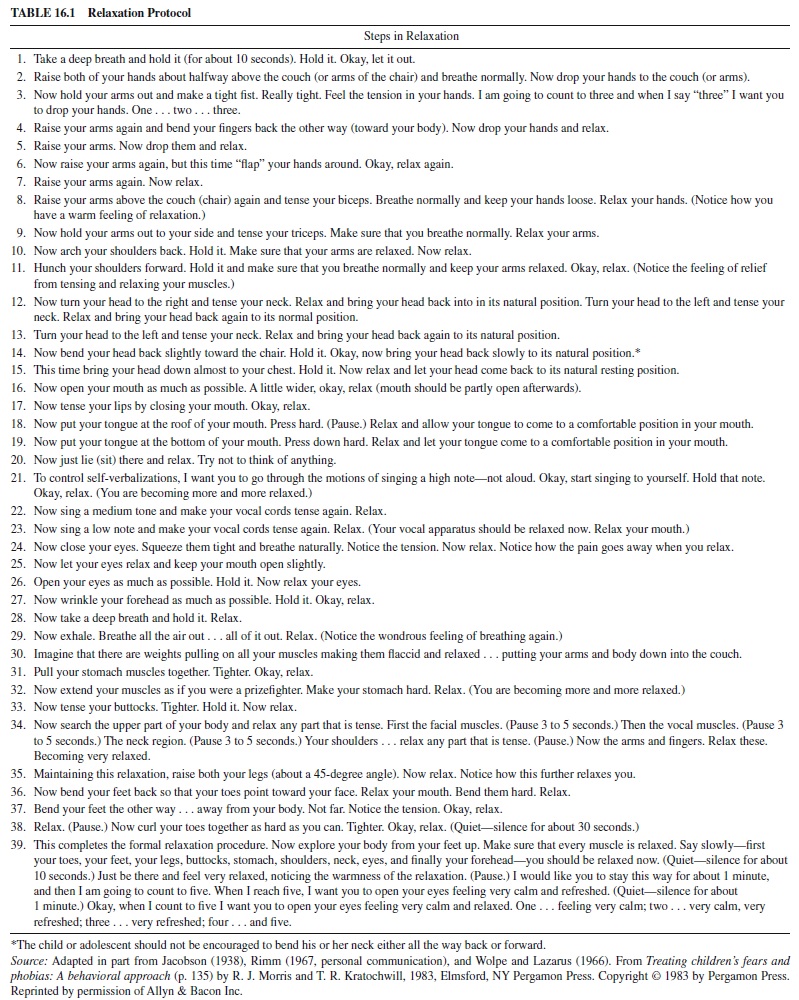

In terms of supportive research, a variety of behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy procedures have been used in the treatment of such child and adolescent behavior disorders as OCD, depression, fears and related anxieties, disruptive behavior disorders such as aggression and conduct disorder, ADHD, psychophysiological disorders including eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and autism (see, e.g., Mash & Terdall, 1997; Mash & Wolfe, 1999; Morris & Kratochwill, 1998c; Morris & Morris, 2000; Quay & Hogan, 1999). For example, regarding children’s and adolescents’fears and phobias, four different types of behaviorally oriented methods have been used successfully to treat this disorder (see, e.g., Morris & Kratochwill, 1983a, 1998c). The first method, systematic desensitization and its variants, presumes that a child’s fear or phobic response is learned and can, therefore, be counter conditioned by teaching the child to relax through the use of a relaxation protocol such as the one shown in Table 16.1. Calmness and trust in the therapeutic relationship has also been used in certain types of desensitization procedures such as in vivo and contact desensitization. The relaxed or calm state that the client experiences is then associated (either through imagination or in vivo) with a graduated hierarchy of fearful or anxietyprovoking situations that the client previously listed with the therapist’s assistance. Contingency management procedures have also been used to treat these behavior difficulties. For example, positive reinforcement has been used to reduce the frequency and duration of social withdrawal and social isolation in young children, as well as to increase social interaction. When combined with shaping, positive reinforcement has also been used to treat school phobia.

Both live and symbolic modeling approaches have also been used to treat children’s fears and phobias. Like contingency management methods, these procedures have been used more often to treat clearly identifiable fears and phobias such as phobias involving nondangerous animals, physical or dental examinations and receiving an injection, attending school, and darkness or sleep anxiety. Cognitivebehavioral therapy procedures that have been used have involved primarily self-instructional and self-control training where the therapist teaches the child how, when, and where to use various cognitions or self-statements to facilitate the learning of new and more adaptive nonfearful behaviors (Morris & Kratochwill, 1998a; Morris & Morris, 2000).

Psychoanalytic Therapy

The origins of psychoanalysis as a psychotherapy method with children and adolescents can be traced back to Sigmund Freud’s (1909) case of Little Hans. Hans was almost 5 years old and was very afraid of horses. His fear that a horse would bite him made him reluctant to leave the house. It was on the basis of these symptoms and other information conveyed to Freud by Hans’s father that Freud formulated his theory of the development of phobias and his position on psychoanalytic therapy with children (Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b).

Freud never saw Hans in therapy. As Freud (1909) stated, “the treatment itself was carried out by the boy’s father” (p. 149). Freud, however, did see Hans “on one single occasion,” during which time he had a “conversation with the boy”; in that regard he stated that he “took a direct share” in the boy’s treatment (p. 149). Freud did not participate directly in Hans’s therapy because he felt that only a parent could adequately act as an analyst for a young child—he felt that a child could not form a trusting enough relationship with a stranger (e.g., analyst) to permit the normal therapeutic interchange that needs to take place in psychoanalysis (Kratochwill, Accardi, & Morris, 1988). Although he did not believe that an analyst could see children directly in therapy, he felt that the use of psychoanalysis with children had the purpose of “empirically” observing the origins of adult neuroses during childhood, and he wanted to confirm his own conceptualization of infantile sexuality, as he hypothesized in his (1905) article titled “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.”

In 1913, Hermine Hug-Hellmuth, the third woman to join Freud’s Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, began conducting psychoanalytic work with children. She wrote about how she invited the children to speak to her using the metaphor of play rather than having them sit on the couch and use the psychoanalytic treatment tool of free association. Based on Hug-Hellmuth’s initial work, Melanie Klein and Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, continued developing this area of play therapy, and during the 1920s to 1930s they established their respective schools of child analysis (Benveniste, 1998). Sigmund Freud’s case of Little Hans therefore laid the groundwork for the formation of a new approach to the psychological treatment of children’s and adolescents’ behavioral and emotional disorders. As Anna Freud (1981) wrote,

What the analysis of Little Hans opened up is a new branch of psychoanalysis, more than the extension of its therapy from adult to child—namely, the possibility of a new perspective on the development of the individual and on the successive conflicts and compromises between the demands of the drive, the ego, and the external world which accompany the child’s laborious steps from immaturity to maturity (p. 278).

Both Klein and Anna Freud discovered that children using the medium of play will represent their inner conflicts, reflect on their views and perceptions of important relationships in their lives, and play out significant aspects of their unique pleasurable and traumatic experiences. The play medium, therefore, permits the child analyst to become attuned to the verbal and nonverbal communications of the child in order to further an understanding of the child’s feelings, worries, wishes, motives, and conflicts (Warshaw, 1997).

Although Anna Freud and Melanie Klein were trained as psychoanalysts, their respective approaches to working with children were different. Anna Freud emphasized theory and pedagogy as part of her procedure, whereas Klein’s approach focused on techniques (e.g., Donaldson, 1996; Viner, 1996). Specifically, Anna Freud believed that psychoanalysis should be a pedagogical tool used to educate children and strengthen their ego functioning. In her writings she emphasized the contribution of child development to the emergence of children’s personality and general emotional functioning— maintaining that the interaction between mental functions and biology were very important in both the understanding of children’s emotionality and the conduct of child psychoanalysis (e.g., Mayes & Cohen, 1996; Neubauer, 1996). She also believed that the transference relationship observed in adult psychoanalysis could not take place in child psychoanalysis, and that her father’s notion of the Oedipus complex should not be an area of investigation with children because the revealing of Oedipal material was too traumatic for a child’s immature ego (Donaldson, 1996; Viner, 1996). Moreover, consistent with Hug-Hellmuth’s position, Anna Freud felt that children could not free associate during therapy because they were not capable of articulating their thoughts and that their play activity in therapy was not equivalent to (or a substitute for) free association (Solnit, 1998). As a result, insight from an analyst’s interpretation of the patient’s free association thinking was not possible with children. Interpretation of dream material was also to be limited to nonOedipal content (Donaldson, 1996; Viner, 1996). Therapy therefore stressed the importance of the therapeutic relationship or therapeutic alliance, the emotional maturing of the child within the therapeutic alliance, and the use of interpretation of ego defenses versus interpretation of deeper unconscious material (O’Connor, Lee, & Schaefer, 1983).

Klein also recognized the language limitations of children. However, unlike Anna Freud, she viewed play activity as the equivalent to free association in adult psychoanalysis. This permitted her to interpret a child’s play as being symbolic of various unconscious beliefs and motives and to introduce Sigmund Freud’s notion of the transference relationship as a viable therapeutic tool in child psychoanalysis (e.g., Donaldson, 1996; Segal, 1990; Viner, 1996). Klein further maintained that although classical psychoanalytic theory does not consider as possible the development of superego functioning early in a child’s life (i.e., prior to the internalization and resolution of the Oedipal conflict), she nevertheless believed that the child’s first relationship with the mother in fact formed the basis of superego development in infancy. Specifically, she felt that the superego develops through the projection of aggressive feelings toward the mother and the introjection of these same feelings as hostile objects in the child’s fantasy (Segal, 1990).

Other than these latter theoretical and treatment differences, Klein and Anna Freud agreed on many aspects of the conduct of child psychoanalysis. In this regard, Scharfman (as cited in O’Connor et al., 1983) pointed out the following similarities in the different forms of child psychoanalysis: (a) There should be few limitations on the direction of treatment, allowing for the analyst to follow the child’s free expression of emotion; (b) interpretation is the basic technique used with defenses as they impede the flow of material that may need to be addressed in analysis; (c) the analyst restricts the use of educative materials or other means to change the child’s environment, intervening only when it is necessary to maintain the continuity of analytic therapy; (d) the goal of therapy is to allow patients to fulfill their development as completely as possible by helping make conscious those unconscious elements that prevent movement toward effective functioning; and (e) the analyst does not place limitations on the various ways in which the patient perceives him or her— the analyst should be used by the patient as an object with whom he or she can interact and in whose presence he or she can feel comfortable with revealing thoughts and feelings about the past, present, and future.

To these latter similarities, we add the following general working assumptions of child and adolescent psychoanalysis: (a) Behavioral problems are not construed as being situation or setting specific; (b) behavioral problems are a symptom of (and thereby caused by) an unconscious conflict—behaviors are viewed as serving a function for the person and represent his or her attempt to cope with inner needs and external realities, and one cannot assume that similar behaviors have the same or a similar cause; (c) the goal of psychoanalysis is specified in a general manner in order to provide the person with the opportunity to fulfill his or her psychological development as completely as possible and to clarify the person’s basic motivations and ways of coping so that he or she can deal with them effectively and develop more adaptive capacities; (d) interpretation on the part of the analyst and insight by the patient are critical for the success of psychoanalysis; and (e) the therapeutic alliance is essential for providing the patient with the opportunity to make progress in fulfilling his or her psychological development.

Contemporary writers in child psychoanalysis have generally adopted Anna Freud’s view that a child’s or adolescent’s developmental stage needs to be taken into consideration when conducting psychoanalysis (e.g., Kennedy & Moran, 1991; Yorke, 1996). For example, when treating children under 5 years of age, issues of cognitive capacity, reality testing, and the capacity for impulse control need to be taken into consideration (Kennedy & Moran, 1991). In the case of adolescents, because these individuals are typically verbal and can free associate, the analyst is more likely to follow a model that is consistent with adult psychoanalysis.The major exception, however, is the recognition by the analyst that the adolescent is still progressing through stages of development—each with its own tasks and conflicts that contribute to the adolescent’s overall process of growth toward individuation and maturity. For example, this is a time when old patterns of relatedness to one’s parents need to be resolved while beginning to establish new patterns based on various social, cognitive, and physiological competencies that take place (Blos, 1979). Moreover, when treating children or adolescents with developmental delays, psychoanalysis should address the developmental need in addition to the analysis of conflicts and defenses (Kennedy & Moran, 1991;Yorke, 1996).

In terms of supportive research, very few controlled outcome studies have documented the efficacy of child or adolescent psychoanalysis (Kazdin, 1990). Most of the literature in this area of psychotherapy is based on clinical case studies like those published in the multivolume compilation titled Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. Edelson (1993) suggested that the case study is especially appropriate for use to support claims concerning the scientific credibility of psychoanalytic explanations of behavior, and he felt that the empirical data derived from case studies further support treatment effectiveness. For example, by combining the results of several case studies regarding the psychoanalytic treatment of children’s fears and anxiety disorders (e.g., A. Freud, 1977; Gavshon, 1990; Goldberg, 1993; Pappenheim & Sewwney, 1952; Sandler, 1989), the effectiveness of this approach can be demonstrated in successfully treating these anxiety disorders.

Although many proponents of child and adolescent psychoanalytic therapy would agree with Edelson regarding the value of case studies in supporting the treatment efficacy, at least one group of writers stated that the “research needs to catch up with the seasoned therapist” (Tuma & Russ, 1993, p. 155). They further suggested that psychoanalytic therapy (as well as psychodynamic therapy in general) “is still more of an art than a science and remains untested. This reality puts it at a disadvantage when compared with other treatment approaches such as behavioral therapy” (p. 155).Tuma and Russ also stated, however, that the “richness” of psychoanalytic and psychodynamic treatments, as well as their “wealth of knowledge” regarding child development, “make it imperative that we carry out sophisticated research studies that will answer specific questions about what interventions affect which specific processes” (p. 155). Moreover, Russ (as cited in Tuma & Russ, 1993) has indicated that if psychoanalytic therapy (and psychodynamic approaches in general) are to continue to be used with children and adolescents, clinical researchers will need to become as specific as behaviorally oriented researchers in analyzing the effectiveness of therapy outcome. Psychoanalytically oriented therapy researchers may also need to consider the findings of the Menninger Foundation’s Psychotherapy Research Project (PRP; Wallerstein, 1994) when evaluating child and adolescent treatment efficacy. Specifically, the PRP reported that psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic therapies were found to be consistently modified in a supportive therapy direction and that more of the achieved changes were based on these supportive mechanisms rather than on interpretive resolution of intrapsychic conflict.

Adlerian Approach

Alfred Adler was educated as a physician and was one of the charter members of Sigmund Freud’s Vienna Psychoanalytic Society (which became known as the “Vienna Circle”), and later became one of its presidents. However, he resigned from the group in 1911 after becoming increasingly at variance with some of the basic tenets of psychoanalysis. Thereafter, he formed his own group, which was known as individual psychology (Kratochwill et al., 1988; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b; Mosak & Maniacci, 1993). Although Adler’s approach can be regarded in part as psychodynamic, it is distinguishable in a number of ways from Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. First, Adler’s approach is “holistic” with the person being viewed as a “totality” that is integrated into a social system. In this regard, the fundamental concepts in Adler’s individual psychology are holism, lifestyle, social interest, and directionality or goals (Fadiman & Frager, 1976). Second, unlike Sigmund Freud, who assumed that human behavior is motivated by inborn instincts, Adler assumed that humans are motivated primarily by social factors (Kratochwill et al., 1988; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b; Mosak & Maniacci, 1993).

Third, Adler introduced the concept of the creative self, which he conceptualized as a highly subjective individualized system that directs a person’s experiences. Another difference between Adler and Sigmund Freud was Adler’s view of the uniqueness of each individual personality. Thus, in contrast to Sigmund Freud’s position, which indicated that sexual instincts were central in personality dynamics, Adler maintained that each individual was a unique configuration of social factors such as motives, interests, traits, and values. Adler’s emphasis on conscious processes represented another major difference between his individual psychology and Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. For Adler, consciousness was the center of personality, whereas for both Sigmund and Anna Freud, as well as Melanie Klein, unconscious processes were the center of personality.Adler did not necessarily deny, however, personality dynamics where some unconscious processes directed the individual (Kratochwill et al., 1988; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b; Mosak & Maniacci, 1993).

Adler did not view deviant behavior or behavior disorders as mental illness. Instead, individuals demonstrating these forms of behavior were said to be involved in mistaken ways of living or mistaken lifestyles. Consistent with his views regarding mistaken lifestyles, Adler believed that deviant behavior could occur in childhood because he felt that the first four or five years of life lay the foundation for the lifestyle. Thus, specific childhood behavior problems were not conceptualized any differently than was any other childhood behavior disorder. For Adler, mistaken lifestyles involve mistakes about oneself, the world, goals of success, and a low level of social interest and activity (Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b). As Mosak (1979) stated, “The neurotic, by virtue of his ability to choose, creates difficulty for himself by setting up a ‘bad me’ (symptoms, ‘ego-alien’ thoughts, ‘bad behavior’) that prevents him from implementing his good intentions” (p. 46).

The assumptions that therefore underlie Adler’s individual psychology include the following: (a) The unconscious is deemphasized in the understanding and treatment of behavior disorders, and consciousness is the center of personality; (b) the theory and therapy are holistic in that the child or adolescent is seen as more than the sum of his or her parts without manifesting internal conflicts between underdeveloped forces such as from the id or ego; (c) the person is viewed as moving toward a goal with the purpose of behavior being goal attainment; (d) consistent with the creative self, an individual will find a way to achieve a goal; (e) behavioral problems are not construed as being situation or setting specific because they are directly related to goal attainment, which can take place in a variety of settings; and (f) behavior is understood within the individual’s social context and social interest (i.e., sense of self-worth and feeling of belonging; Ansbacher, 1991; Dreikurs & Soltz, 1964; Edwards & Kern, 1995; Leak & Williams, 1991; Morris & Kratochwill, 1983b; Mosak & Maniacci, 1993).

Adler’s notion of goal attainment is relevant to child and adolescent psychotherapy in that it implies that children’s and adolescents’ misbehaviors are best construed in terms of having a purpose. These purposes or goals are the following: (a) attention getting, (b) struggle for power or superiority, (c) desire to retaliate or get even, and (d) display of inadequacy or assumed disability (Dreikurs & Soltz, 1964). In this regard, Adlerian child and adolescent therapists believe that children who use attention-getting techniques desire attention so much that they will even seek attention by engaging in such negative behaviors as annoying others. Children whose goal is power or superiority will engage in behaviors or activities that show that they can do whatever they want and will not do what is asked of them by others. When the goal is retaliation or revenge, children or adolescents will engage in behaviors that will hurt others, embarrass others, or cause some sort of obvious discomfort in others—wanting, in essence, to create a mutual antagonism. When children or adolescents have a goal of displaying inadequacy, they will engage in behaviors that show that they are discouraged and cannot believe that they are important or significant. By engaging in these latter behaviors, the child or adolescent establishes a level of self-protection from failing at anything that is expected or asked of him or her and therefore decreases the chances that he or she will be required to do something. In other words, they are protected from trying and failing (Bitter, 1991; Dinkmeyer, Dinkmeyer, & Sperry, 1987; Kottman & Stiles, 1990; Mosak & Maniacci, 1993).

With respect to therapy outcome research, Mosak and Maniacci (1993) have indicated that research in this area is “generally geared to causalistic factors, andAdlerian psychology emphasizes purposes, not causes, making research appear somewhattooconstraining”(p.180).Theyconcludedthat“the literature on research in the area of [Adlerian] child psychotherapy research is severely lacking” (p. 180). Although therapy outcome research is sparse, there have been studies investigating the impact of various Adlerian constructs on children’s behaviors (e.g., Appleton & Stanwyck, 1996; Clark, 1995; Edwards & Kern, 1995; Kern, Edwards, Flowers, Lambert, & Belangee, 1999). For example, Edwards and Kern (1995) studied the impact of teachers’ social interest on children’s classroom behavior and found that teachers’ social interest was negatively correlated with student disruptive behavior and scores on the Impatient-Aggression subtest of the Behavior Rating Checklist.Apositive correlation was also found between teachers’ social interest and children’s cooperative attitudes. Edwards and Kern suggested that these results showed that teachers who have a positive sense of self, concern for others, and healthy psychological well-being may perceive their students as being less aggressive and impatient toward other students, themselves, and the teacher him- or herself.The researchers further suggested that these latter teachers may also be more likely to perceive students as not presenting typical classroom misbehaviors and may be more likely to attend to teacher instructions and work given by the teacher.

Client-Centered (Humanistic) Therapy

The client-centered approach to child and adolescent psychotherapy is based on the personality theory and psychotherapy writings of Carl Rogers (1942, 1946, 1947, 1951, 1959). Although he is best known for his work with adults, Rogers’s focus in graduate school was on children, as was his emphasis during his first 10 years of employment as a clinical psychologist at a child guidance clinic in Rochester, New York. In fact, his doctoral dissertation at the Teachers College of Columbia University was a study involving the clinical assessment of children. Moreover, his first book, Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child (Rogers, 1939), was in the area of child psychotherapy, and in the 1940s at Ohio State University Rogers taught a clinical practicum course involving the administration and interpretation of children’s intelligence and personality tests (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993).

It was not until Rogers went to the University of Chicago in 1945 that he focused his writings and practice entirely on counseling and psychotherapy with adults, refining his views and elaborating on them in later years at the University of Wisconsin (at Madison), Stanford University, Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, and the Center for Studies of the Person.

Although Rogers wrote about personality development and psychotherapy, he did not address in detail the development or etiology of specific types of behavior disorders or forms of psychopathology in either adults or children, preferring to focus on what he referred to as psychological maladjustment in the individual. For example, he listed the following conclusions regarding the characteristics of the individual:

-

The individual possesses the capacity to experience in awareness the factors in his psychological maladjustment, namely, the incongruence between his self-concept and the totality of his experience.

-

The individual possesses the capacity and has the tendency to reorganize his self-concept in such a way as to make it more congruent with the totality of his experience, thus moving himself away from a state of psychological maladjustment and towards a state of psychological adjustment.

-

These capacities and this tendency, when latent rather than evident, will be released in any interpersonal relationship in which the other person is congruent in the relationship, experiences unconditional positive regard toward, and empathic understanding of, the individual, and achieves some communication of these attitudes to the individual. (Rogers, 1959, p. 221)

Certain assumptions regarding client-centered therapy are inherent in these statements. First, there is Rogers’ central hypothesis, namely, that “the individual has the capacity to guide, regulate, and control himself, providing only that certain definable conditions exist” (Rogers, 1959, p. 221). Second, given the presence of the appropriate “definable conditions,” the individual himself or herself is the only one capable of moving towards self-actualization. Third, the appropriate definable conditions for the individual to move away from “psychological maladjustment” are unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding provided within the context of a relationship with a therapist who is congruent with the individual. In this regard, the therapist does not act as an “advisor” to the individual or as an “expert analyst and interpreter, or galvanizer of emotional expression” (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993, p. 259). Rogers also indicated that this latter assumption applies to children as well as adults. Thus, inherent in client-centered therapy is respect for the individual’s self-directing capacities. Fourth, diagnostic or personality assessment of the individual is antithetical to the basic assumptions underlying client-centered therapy. From Rogers’point of view, diagnostic assessment is used in psychoanalysis to categorize the client within the context of the therapist’s theory of psychopathology. Similarly, within a behavioral or Adlerian approach, the purpose of a diagnostic assessment is to focus on the specific problem or purpose that the therapist will select for intervention. Whereas each of these latter three approaches can be construed as problemoriented therapies, client-centered therapy “does not have the goal of eliminating problems defined by the clinician, but rather the goal is to resolve conflicts that are meaningful [to the individual]” and in a manner consistent with the individual’s movement toward self-actualization (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993, pp. 262–263).

To these latter assumptions, we add the following general working assumptions of client-centered therapy: (a) psychological maladjustment is not situation or setting specific; (b) instead of behavioral problems being the focus of therapy, resolving conflicts that are construed as meaningful to the individual is the focus of therapy; (c) therapy focuses not on the unconscious but on those issues and concerns that the individual experiences and is aware of in his or her movement toward psychological adjustment; and (d) the goal of client-centered therapy is specified in a general manner—to provide the individual with the opportunity to move himself or herself away from psychological maladjustment and toward a state of psychological adjustment and selfactualization (e.g., Ruthven, 1997).

The person who is most credited with advancing clientcentered therapy with children and adolescents is Virginia Axline (1947), one of Rogers’s former students who joined him at the University of Chicago’s Counseling Center and later went to Columbia University’s Teachers College (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993). Axline was an outstanding writer who was able to capture in her writings the intricacies of conducting client-centered child therapy. Another early writer in client-centered child therapy was Elaine Dorfman (1951), who wrote a chapter on client-centered play therapy in Rogers’s (1951) book Client-Centered Therapy.

In her book Play Therapy, Axline (1947) identified eight principles underlying a client-centered therapy approach to working with children:

-

The therapist must develop a warm, friendly relationship with the child, in which good rapport is established as soon as possible.

-

The therapist accepts the child exactly as he is.

-

The therapist establishes a feeling of permissiveness in the relationship so that the child feels free to express his feelings completely.

-

The therapist is alert to recognize the feelings the child is expressing and reflects those feelings back to him in such a manner that he gains insight into his behavior.

-

The therapist maintains a deep respect for the child’s ability to solve his own problems if given the opportunity to do so. The responsibility to make choices and institute change is the child’s.

-

The therapist does not attempt to direct the child’s actions or conversation in any manner. The child leads the way; the therapist follows.

-

The therapist does not attempt to hurry the therapy along. It is a gradual process and is recognized as such by the therapist.

-

The therapist establishes only those limitations that are necessary to anchor the therapy to the world of reality and to make the child aware of his responsibility in the relationship. (Axline, 1947, pp. 73–74)

Consistent with Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, Axline believed that play formed an integral part of psychotherapy, permitting the child to express himself or herself through various verbal and nonverbal activities. However, unlike Freud and Klein, Axline believed that a child’s activities in the play therapy room did not need to be directed or interpreted by the therapist. As Axline stated, “The child leads the way; the therapist follows” (p. 73). She also believed that some adolescents in client-centered therapy may choose to use the play therapy room whereas others may feel uncomfortable in this room. Similarly, she believed that some younger children may prefer the therapist’s office over the play therapy room.

With respect to therapy outcome research, the amount of research supporting the efficacy of client-centered child therapy has lagged behind the quantity of similar research with adults (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993). Dorfman (1951), for example, cited a number of process-oriented and therapy outcome studies with children, and other therapy process studies subsequent to Dorfman’s review have been published (e.g., Lebo, 1955). She also pointed out the many difficulties in conducting this type of research with children in play therapy. Seeman (1983) also summarized some of the research findings in this area, as have Ellinwood and Raskin (1993). For example, using teacher and peer ratings, research has demonstrated that children undergoing client-centered therapy improve over those in a control group. In addition, client-centered therapy has contributed to improvement on personality and achievement scores of children.

Comparison Outcome Studies

Research studies comparing the outcome of different types of child and adolescent psychotherapies is limited, although, as was mentioned earlier, several meta-analytic studies (e.g., Casey & Berman, 1985; Weisz, 1998; Weisz et al., 1987; Weisz et al., 1995) have suggested that the average outcome for children receiving child psychotherapy was appreciably better than those children not receiving therapy. The findings further suggested that the average positive outcome for the behavior therapies was appreciably higher than for the other types of child-oriented therapies, with no particular behavior therapy procedure found to be better than any other behavior therapy method. The results of two of these studies (i.e., Weisz et al., 1987; Weisz et al., 1995), however, were affected by whether the sample was limited to children versus adolescents, while the findings of another study (i.e., Casey & Berman, 1985) were influenced by certain child characteristics in that treatments involving children having aggression or social withdrawal were not as effective as treatments for hyperactivity, somatic difficulties, and phobias.

Consistent with the previous findings regarding behaviorally oriented therapies, Ellinwood and Raskin (1993) reported on a comparison outcome study conducted in Germany in 1981 by Dopfner, Schhluter, and Rey. Ellinwood and Raskin reported that these researchers compared client-centered play therapy with a behaviorally oriented social skills training (SST) program for nonassertive children. Dopfner et al. found that the SST approach was “effective in reducing social anxiety, low self-concept, low frequency of social interaction, low ability to behave normally in social interactions, and overall maladjustment. Play therapy appeared to reduce only social anxiety” (Ellinwood & Raskin, 1993, p. 273).

In one of the few data-based studies on the most frequently applied child and adolescent therapy procedures used by clinicians, Kazdin, Siegel and Bass (1990) found that behavioral, cognitive, eclectic, psychodynamic, and family therapies were rated as “most useful” by the psychologists and psychiatrists that were surveyed. The psychologists in the study rated behavior modification and cognitive therapy approaches as more useful than did the psychiatrists, whereas the psychiatrists rated psychoanalytic approaches as more useful than did the psychologists. In addition, Kazdin et al. stated, “The majority of either psychologists or psychiatrists, but not both, felt that psychodynamic therapy, play therapy, behavior modification, and cognitive therapy were very effective” (p. 196).

Comparison outcome studies are among the most difficult psychotherapy studies to conduct. The reasons for this are many (see, e.g., Kazdin, 1990, 1993, 1997; Kendall & Morris, 1991; Mash & Wolfe, 1999; Weisz, 1998). First, to be clinically meaningful, the studies should be conducted within clinic settings (vs. laboratory settings) by clinicians who are experienced (and competently trained) in the application of the particular method being used. Second, the child or adolescent clients should each be clinic-referred clients (vs. being recruited from advertisements), and the type, severity, and chronicity of each client’s behavior disorder should be equated across treatment groups. Third, clients having comorbidity diagnoses should be equated across treatment groups, as should relevant demographic variables such as the gender, age, IQ, and socioeconomic status (SES) of clients. Fourth, treatment integrity across and within clinicians needs to be assessed for each type of therapy being administered to be assured that the treatments were carried out as intended. Fifth, follow-up assessment needs to take place to determine whether treatment outcome at posttest is maintained over time. Sixth, multimethod outcome assessments should be conducted in an objective manner, and where appropriate, interjudge reliability coefficients should be calculated to assure all involved that judges were in agreement regarding the observation of positive, negative, or no behavior change. Moreover, whenever possible, child or adolescent self-report, as well as behavior change data from parents, teachers, and peers should be obtained. Archived data, such as number of tardies at school, number of absences from school, number of trips to the principal’s office, number of visits to the nurse’s office, and so on, may also be useful in determining outcome in treatment comparison studies. Consistent with the more prescriptive questions posed earlier, it might be best initially to limit a comparison outcome study to the investigation of children or adolescents (not both) who have only one specific behavior disorder (e.g., ADHD, OCD, or separation anxiety). Additional limitations can be made regarding SES, duration of behavior disorder, no comorbidity diagnosis, and so on; however, it should be recognized that the generalizability of one’s findings may appreciably decrease as the limitations imposed in the study increase.

In addition to the previous considerations, proponents of particular child and adolescent therapies have maintained that in order to make a fair comparison of their therapy approach with other approaches, certain assessment measures, which may be considered nontraditional dependent measures by proponents of other therapy approaches, need to be included in this type of outcome research. For example, Szapocznik et al. (1993) developed the Psychodynamic Child Ratings. They maintain that when child psychoanalysis is compared to other child therapies in terms of treatment outcome, an inaccurate assessment of its efficacy occurs because of the lack of “appropriate” measurement methods being utilized. Specifically, they believe that measures used in such outcome studies focus primarily on symptomatic and behavioral changes rather than on psychodynamic processes. As a result, they developed the Psychodynamic Child Ratings to evaluate the effect of child psychoanalysis. The scale produces a total score for psychodynamic functioning, as well as scores on two factorial derived scales: interpersonal and intrapersonal functioning. Little research, however, has been published using this scale.

Proponents of other child and adolescent therapies have made comments similar to those of Szapocznik et al. (1993). For example, Mosak and Maniacci (1993) indicated earlier that Adlerian psychology emphasizes purposes instead of causes and that this therefore makes outcome research “appear somewhat too constraining.” Both positions seem to support the view that before any clinically meaningful comparison outcome research is conducted, not only do many of the aforementioned variables need to be taken into consideration, but also proponents of the child or adolescent therapies being studied must agree to (and find acceptable) the dependent measures being utilized.

Conclusions and Future Directions for Research

There is little doubt from the child and adolescent psychotherapy literature that some form of treatment is better than no treatment and that for such behavioral problems as hyperactivity, somatic complaints, and phobias the behavior therapies are better than are other child psychotherapy approaches. We are also learning that the question, “Is child or adolescent psychotherapy effective?” is no longer a question that needs to be answered because any answer is not necessarily going to be clinically meaningful—that is, there is not a one-size-fits-all type of child or adolescent psychotherapy. The field needs to be oriented toward answering more prescriptive questions, such as “Which child therapy procedure is most effective for children having a primary diagnosis of ADHD and whose parents do not have sufficient time to be consultants to the clinician?” or “Which adolescent therapy method is most effective for inpatient female adolescents having a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder and who are on a therapeutic dosage of antidepressant medication?” Answers to these types of questions will maximally advance the area of child and adolescent psychotherapy.

Other advances in research that need to take place involve making sure that psychotherapy outcome research focuses mainly on the treatment of children or adolescents who have a clinically derived (and independently verified) psychiatric diagnosis and are treated in mental health clinic or hospital settings versus university-based clinical laboratories or other institutional research settings. Moreover, the therapists providing the treatment should be experienced and competent in the application of the therapies being studied. Researchers also need to determine the contribution to treatment outcome of therapeutic relationship variables, as well as such variables as therapist and client ethnicity, cultural background, and values. In addition, as mentioned earlier, the relative contribution of a comorbid diagnosis needs to be assessed in relation to therapy outcome for both children and adolescents having the same primary diagnosis.

Child and adolescent psychotherapy has made many advances since the initial work of Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, and we fully expect great progress toward prescriptive treatments in this area and the development of empirically supported guidelines for treating children and adolescents with specific behavior disorders. At present, however, of the four forms of child and adolescent psychotherapy reviewed, no one can state with any certainty which types of treatment should be used with which types of children or adolescents under which types of conditions.

Bibliography:

- Allen, E. H. (1942). Psychotherapy with children. New York: Ronald Press.

- Ansbacher, H. L. (1991). The concept of social interest. Individual Psychology, 47, 28–46.

- Appleton, B. A., & Stanwyck, D. (1996). Teacher personality, pupil control, ideology, and leadership style. Individual Psychology, 52, 119–129.

- Arambulla, D., DeKraai, M., & Sales, B. (1993). Law, children, and therapists. In T. R. Kratochwill & R. J. Morris (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy with children and adolescents (pp. 583–619). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Axline, V. (1947). Play therapy: The inner dynamics of childhood. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Bandura, A. (1969). Principles of behavior modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A., & Walters (1963). Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Barkley, R. A. (1990). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

- Bear, G. C., Minke, K. M., & Thomas, A. (Eds.). (1997). Children’s needs:Vol.2.Development,problems,andalternatives.Bethesda, MD: NationalAssociation of School Psychologists.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press.

- Benveniste, D. (1998). Play and the metaphors of the body. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 53, 65–83.

- Bernard, M. E., & Joyce, M. R. (1993). Rational-emotive therapy with children and adolescents. In T. R. Kratochwill & R. J. Morris (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy with children and adolescents (pp. 221–246). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Beutler, L. (1997). The psychotherapist as a neglected variable in psychotherapy: An illustration by reference to the role of therapist experience and training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4, 44–52.

- Bitter, J. R. (1991). Conscious motivations: An enhancement to Dreikurs’ goals of children’s misbehavior. Individual Psychology, 47, 210–221.

- Blos, P. (1979). The adolescent passage. New York: International Universities Press.

- Casey, R. J., & Berman, J. S. (1985). The outcome of psychotherapy with children. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 388–400.

- Clark, A. J. (1995). The organization and implementation of a social interest program in the schools. Individual Psychology, 51, 317– 331.

- D’Amato, R. C., & Rothlisberg, B. A. (Eds.). (1997). Psychological perspectives on intervention. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

- DeKraai, M., Sales, B., & Hall, S. (1998). Informed consent, confidentiality, and duty to report laws in the conduct of child therapy. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (3rd ed., pp. 540–560). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Dinkmeyer, D. C., Dinkmeyer, D. C., Jr., & Sperry, L. (1987). Adlerian counseling and psychotherapy (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill.

- Donaldson, G. (1996). Between practice and theory: Melanie Klein, Anna Freud and the development of child analysis. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 32, 160–176.

- Dorfman, E. (1951). Play therapy. In C. R. Rogers (Ed.), Clientcentered therapy (pp. 235–277). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Dreikurs, R., & Soltz, V. (1964). Children: The challenge. New York: Meredith Press.

- Edelson, M. (1993). Telling and enacting stories in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy: Implications for teaching psychotherapy. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 48, 293–325.

- Edwards, D., & Kern, R. (1995). The implications of teachers’ social interest on classroom behavior. Individual Psychology, 51, 67–73.

- Ellinwood, C., & Raskin, N. J. (1993). Client-centered/humanistic psychotherapy. In T. R. Kratochwill & R. J. Morris (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy with children and adolescents (pp. 258– 287). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Stuart.

- Ellis, A., & Wilde, J. (2002). Case studies in rational emotive behavior therapy with children and adolescents. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Fadiman, J., & Frager, R. (1976). Personality and personal growth. New York: Harper and Row.

- Freud, A. (1977). Fears, anxieties, and phobic phenomena. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 32, 85–90.

- Freud, A. (1981). Foreword to “‘Analysis of a phobia in a five-yearold boy’.” In A. Freud (Ed.), The writings of Anna Freud, 1970–1980 (Vol. 8, pp. 277–282). New York: International University Press.

- Freud, A., Hartman, H., & Kris, E. (Eds.). (1945). The psychoanalytic study of the child (Vol. 1, pp. 1–423). New York: International Universities Press.

- Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 125–245). London: Hogarth.

- Freud, S. (1909). The analysis of a phobia in a five-year-old boy. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The Standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 10, pp. 1–149). London: Hogarth.

- Gardner, W. I. (1971). Behavior modification: Applications in mental retardation. Chicago: Aldine.

- Gavshon, A. (1990). The analysis of a latency boy: The developmental impact of separation, divorce, and remarriage. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 45, 217–233.

- Goldberg, M. (1993). Enactment and play following medical trauma: An analytic case study. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 50, 252–271.

- Goldstein, A. P., Heller, K., & Sechrest, L. (1966). Psychotherapy and the psychology of behavior change. New York: Wiley.

- Graziano, A. M. (Ed.). (1971). Behavior therapy with children. Chicago: Aline.

- Heincke, C. M., & Goldman, A. (1960). Research on psychotherapy with children: A review and suggestions for further study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 30, 483–494.

- Hughes, J. (Ed.). (1988). Cognitive behavior therapy with children in schools. New York: Guilford.

- Hull, C. (1943). Principles of learning. New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts.

- Huppert, J. D., Bufka, L. F., Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Woods, S. W. (2001). Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive-behavior therapy outcome in a multicenter trial for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 747–755.

- Itard, J. M. C. (1962). L’enfant sauvage [The wild boy of Aveyron’] (G. Humphrey & M. Humphrey, Trans.). New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts.

- Kanner, L. (1948). Child psychiatry. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Karoly, P., & Kanfer, F. H. (Eds.). (1982). Self-management and behavior change: From theory to practice. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

- Kauffman, J. M. (1981). Characteristics of children’s behavior disorders. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

- Kavale, K. A., Forness, S. R., & Walker, H. M. (1999). Interventions for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In H. C. Quay & A. E. Hogan (Eds.), Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders (pp. 441–454). New York: Kluwer Academic.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Behavior modification in applied settings (Rev. ed.). Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1990). Psychotherapy for children and adolescents. Annual Reviews in Psychology, 41, 21–54.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1993). Research issues in child psychotherapy. In T. R. Kratochwill & R. J. Morris (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy with children and adolescents (pp. 541–565). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1997). The therapist as a neglected variable in psychotherapy research [Special section]. Clinical Psychology, Science and Practice, 4, 40–89.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2000). Behavior modification in applied settings (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomas Learning.

- Kazdin, A. E., Siegel, T. C., & Bass, D. (1990). Drawing on clinical practice to inform research on child and adolescent psychotherapy: Survey of practitioners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 21, 189–198.

- Kazdin, A. E., Siegel, T., & Bass, D. (1992). Cognitive problemsolving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 733–747.

- Kendall, P. C. (Ed.). (1991). Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kendall, P. C. (Ed.). (1992). Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kendall, P. C. (1994). Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 100–110.

- Kendall, P. C., Brady, E. U., & Verduin, T. L. (2001). Comorbidity in childhood anxiety disorders: Effect on treatment outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 787–794.

- Kendall, P. C., & Braswell, L. (1985). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for impulsive children. New York: Guilford Press.

- Kendall, P. C., & Morris, R. J. (1991). Child therapy: Issues and recommendations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 777–784.

- Kennedy, H., & Moran, G. (1991). Reflections on the aim of child analysis. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 46, 181–198.

- Kern, R. M., Edwards, D., Flowers, C., Lambert, R., & Belangee, S. (1999). Teachers’lifestyles and their perceptions of students’behaviors. Journal of Individual Psychology, 55, 422–436.

- King, N. J., Hamilton, D. I., & Ollendick, T. H. (1988). Children’s phobias: A behavioral perspective. New York: Wiley.

- Kottman, T., & Stiles, K. (1990). The mutual story-telling technique: An Adlerian application in child therapy. Individual Psychology, 46, 148–156.

- Kratochwill, T. R., Accardi, A., & Morris, R. J. (1988). Anxiety and phobias: Psychological therapies. In J. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of treatment approaches in child psychopathology (pp. 249–276). New York: Plenum Press.

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Morris, R. J. (Eds.). (1993). Handbook of psychotherapy with children and adolescents. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Leak, G., & Williams, D. (1991). Relationship between social interest and perceived family environment. Individual Psychology, 47, 159–165.

- Lebo, D. (1955). Quantification of the nondirective play therapy process. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 86, 375–378.

- Levitt, E. (1957). The results of psychotherapy with children: An evaluation. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 189–196.

- Levitt, E. (1963). Psychotherapy with children: Afurther evaluation. Behaviour, Research, and Therapy, 6, 326–329.

- Lovass, I. O., & Bucher, B. D. (Eds.). (1974). Perspectives in behavior modification with deviant children. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Mahoney, M. J. (1974). Cognition and behavior modification. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

- Mash, E. J., & Barkley, R. A. (Eds.). (1989). Treatment of childhood disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Mash, E. J., & Terdall, L. G. (Eds.). (1997). Assessment of childhood disorders (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Mash, E. J., & Wolfe, D. A. (1999). Abnormal child psychology. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Mayes, L. C., & Cohen, D. J. (1996). Anna Freud and developmental psychoanalytic psychology. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 51, 117–141.

- Morris, R. J. (1976). Behavior modification with children: A systematic guide. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop Publishers.

- Morris,R.J.(1985).Behaviormodificationwithexceptionalchildren: Principles and practices. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

- Morris, R. J., & Kratochwill, T. R. (Eds.). (1983a). The practice of child therapy. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Morris, R. J., & Kratochwill, T. R. (1983b). Treating children’s fears and phobias. A behavioral approach. New York: Pergamon

- Morris, R. J., & Kratochwill, T. R. (1998a). Fears and phobias. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (3rd ed., pp. 91–131). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Morris, R. J., & Kratochwill, T. R. (Eds.). (1998b). Historical context of child therapy. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (3rd ed., pp. 1–4). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Morris, R. J., & Kratochwill, T. R. (Eds.). (1998c). The practice of child therapy (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Morris, R. J., & Morris, Y. P. (1997). A behavioral approach to child and adolescent psychotherapy. In R. C. D’Amato & B. A. Rothlisberg (Eds.), The quest for answers: A comparative study of intervention models through case study (pp. 21–47). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.