Sample Replication Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

‘Replication’ refers to the repetition of the same or very similar research study. The term ‘replication study’ refers to a study conducted specifically to verify the results of an earlier study. The concept of replication of research studies is central to the scientific study of psychology and the social and behavioral sciences more generally, as many authors have pointed out in Neuliep (1991).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Importance Of Replication

Scientists of all disciplines have long been aware of the importance of replication to their enterprise. Now, thanks to the efforts of science writers for daily newspapers and reporters for network news, even the general public has become aware of the importance of replication in all the sciences.

The undetected equipment failure, the rare and possibly random human errors of procedure, observation, recording, computation, or report, are known well enough to make scientists wary of the unreplicated experiment. When we add to the possibility of the random ‘fluke’ common to all sciences, the fact of individual organismic differences and the possibility of systematic experimenter effects, the importance of replication looms larger still to the behavioral scientist.

What shall we mean by ‘replication’? Clearly, the same experiment can never be repeated by a different worker. Indeed, the same experiment can never be repeated even by the same experimenter. At the very least, the participants and the experimenters themselves are different over a series of replications. The participants are usually different individuals, and the experimenter changes over time, if not necessarily dramatically. But to avoid the conclusion that there can be no replication in the social and behavioral sciences, we can speak of relative replications. We can rank order experiments on how close they are to each other in terms of participants, experimenters, tasks, and situations. We can usually agree that this experiment, more than that experiment, is like a given paradigm experiment.

Replications may be crucial, but some replications are more crucial than others. Three of the variables affecting the value, or utility, of any particular replication are:

(a) when the replication is conducted

(b) how the replication is conducted

(c) by whom the replication is conducted.

1.1 When The Replication Is Conducted

Replications conducted early in the history of a particular question are usually more useful than replications conducted later in the history of a particular research question. Weighting all replications equally, the first replication doubles our information about the research issue, the fifth replication adds 20 percent to our information level, and the fiftieth replication adds only 2 percent to our information level. Once the number of replications grows to be substantial, subsequent investigators’ felt need for further replication is likely to be due not to a real need for further replication but for a real need for the more adequate evaluation and summary of the replications already available.

1.2 How The Replication Is Conducted

It has already been noted that replications are possible only in a relative sense. However, there is a distribution of possible replications in which the variance is generated by the degree of similarity to the original study that characterizes each possible replication. If we choose our replications to be as similar as possible to the study being replicated, we may be more true to the original idea of replication but we also pay a price; that price is external validity.

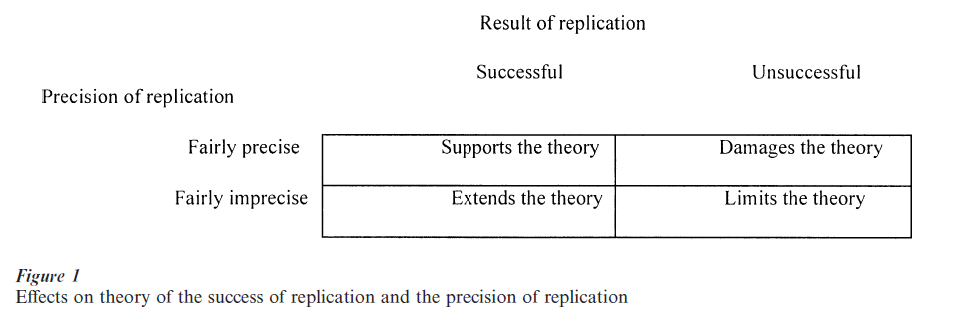

If we conduct a series of replications as exactly like the original as we can, we have succeeded in ‘replicating’ but not in extending the generality of the underlying relationship investigated in the original study. The more imprecise the replications, the greater the benefit to the external validity of the tested relationship if the results support the relationship. If the results do not support the original finding, however, we cannot tell whether that lack of support stems from the instability of the original result or from the imprecision of the replications. Figure 1 summarizes the consequences for the theory that is derived from the initial study of (a) successful vs. unsuccessful replications, and (b) the precise vs. the imprecise nature of the replications.

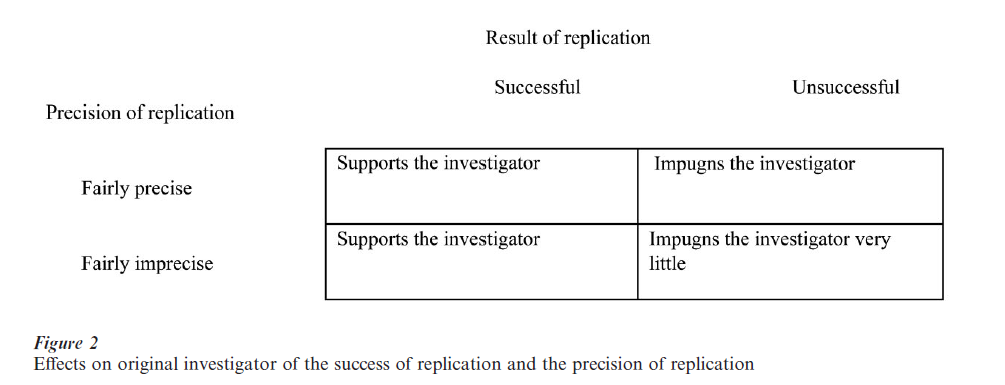

Figure 2 summarizes the consequences for the original investigator of (a) successful vs. unsuccessful replications, and (b) the precise vs. imprecise nature of the replications. Compared to the theory tested by the replication, the investigator has much to lose if a fairly precise replication is unsuccessful since such failure is often associated with ascriptions to the original investigator of having been careless, incompetent, and in some cases, even dishonest.

1.3 By Whom The Replication Is Conducted

So far in our discussion of replications we have assumed that the replications are independent of one another. But what does independence mean? The usual minimum requirement for independence is that the participants in the replication studies be different persons. But what about the independence of the replicators? Are 10 replications conducted by a single investigator as independent of one another as 10 replications each of which is conducted by a different investigator? This issue of potentially correlated replicators bears additional comment.

1.4 The Problem Of Correlated Replicators

To begin with, an investigator who has devoted her life to the study of vision, or of psychological factors in somatic disorders, is less likely to carry out a study of verbal learning than the investigator whose interests have always been in the area of verbal learning. To the extent that (a) experimenters with different research interests are different kinds of people, and to the extent that (b) it has been shown that different kinds of people, experimenters, are likely to obtain different data from their subjects, we are forced to the conclusion that within any area of behavioral research, the experimenters come precorrelated by virtue of their common interests and any associated characteristics. Immediately, then, there is a limit placed on the degree of independence we may expect from workers or replications in a common vineyard. But for different areas of research interest the degree of correlation or similarity among its workers may be quite different. Certainly we all know of workers in a common area who obtain data quite opposite from that obtained by colleagues. The actual degree of correlation, then, may not be very high. It may, in fact, even be negative, as with investigators holding an area of interest in common, but holding opposite expectancies about the results of any given experiment.

A common situation in which research is conducted nowadays is within the context of a team of researchers. Sometimes these teams consist entirely of colleagues; often they are composed of one or more faculty members and postdoctoral students, and one or more predoctoral students at various stages of progress toward the Ph.D. Experimenters within a single research group may reasonably be assumed to be even more highly intercorrelated than any group of workers in the same area of interest who are not within the same research group. Perhaps students in a research group are more likely than a faculty member in the research group to be more correlated with their major professor. There are two reasons for this likelihood. The first is a selection factor. Students may elect to work in a given area with a given investigator because of their perceived and/or actual similarity of interest and associated characteristics. Colleagues are less likely to select a university, area of interest, and specific project because of a faculty member at that university. The second reason why students may be more correlated with their professor than another professor is a training factor. Students may have had a large proportion of their research experience under the direction of a single professor. Another professor, though collaborating with colleagues, has most often been trained in research elsewhere by another person. Although there may be exceptions, even frequent ones, it seems reasonable, on the whole, to assume that student researchers are more correlated with their advisor than another advisor might be.

The correlation of replicators that we have been discussing refers directly to a correlation of attributes and indirectly to a correlation of data these investigators will obtain from their subjects. The issue of correlated experimenters or observers is by no means a new one. Nearly 100 years ago Karl Pearson spoke of ‘the high correlation of judgments…[suggesting] an influence of the immediate atmosphere, which may work upon two observers for a time in the same manner’ in his ‘On the mathematical theory of errors of judgment with special reference to the personal equation’ (Pearson 1902, p. 261).

2. The Meaning Of Successful Replication

There is a long tradition in psychology of our urging one another to replicate each other’s research. But, although we have been very good at calling for replications, we have not been too good at deciding when a replication has been successful. The issue we now address is: when shall a study be deemed successfully replicated?

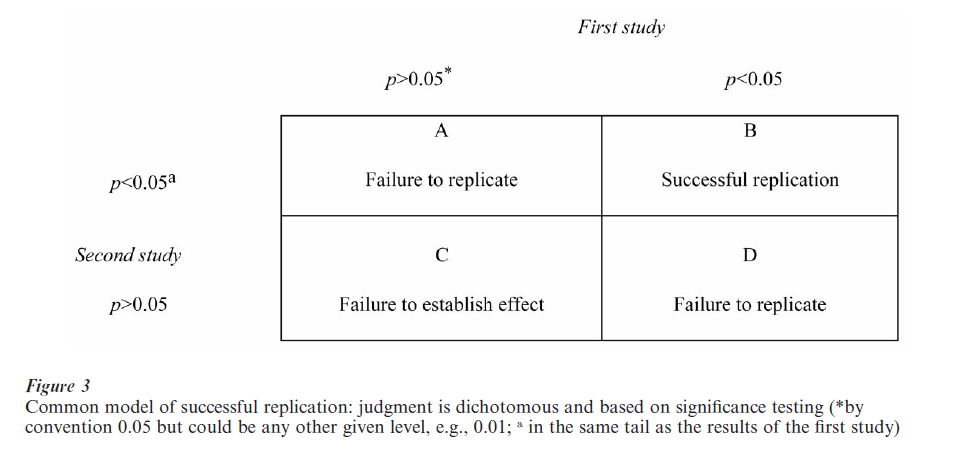

Successful replication is ordinarily taken to mean that a null hypothesis that has been rejected at time 1 is rejected again, and with the same direction of outcome, on the basis of a new study at time 2. The basic model of this usage can be seen in Fig. 3. The results of the first study are described dichotomously as p < 0.05 or p > 0.05 (or some other critical level, e.g., 0.01). Each of these two possible outcomes is further dichotomized as to the results of the second study as p < 0.05 or p > 0.05 . Thus cells A and D of Fig. 3 are examples of failure to replicate because one study was significant and the other was not. The problem with this older view of replication is that two studies could show identical magnitudes of the effect investigated yet differ in significance level because of differences in sample sizes.

2.1 Contrasting Views Of Replication Success

The traditional, not very useful view of replication modeled in Fig. 3 has two primary characteristics:

(a) It focuses on significance level as the relevant summary statistic of a study.

(b) It makes its evaluation of whether replication has been successful in dichotomous fashion. For example, replications are successful if both or neither p < 0.05 (or 0.01, etc.), and they are unsuccessful if one p < 0.05 (or 0.01, etc.) and the other p > 0.05 (or 0.01, etc.). Psychologists’ reliance on a dichotomous decision procedure accompanied by an untenable discontinuity of credibility in results varying in p levels has been well documented, for example, by Nan Nelson, Robert Rosenthal and Ralph L. Rosnow (1986).

The newer, more useful views of replication success have two primary characteristics:

(a) A focus on effect size as the more important summary statistic of a study with only a relatively minor interest in the the statistical significance level.

(b) An evaluation of whether replication has been successful made in a continuous fashion. For example, two studies are not said to be successful or unsuccessful replicates of each other, but rather the degree of failure to replicate is specified.

Bibliography:

- Campbell D T 1988 Overman E S (ed.) Methodology and Epistemology for Social Science: Selected Papers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cooper H M 1989 Integrating Research: A Guide For Literature Reviews, 2nd edn. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Hunt M 1997 How Science Takes Stock. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

- Light R J, Pillemer D B 1984 Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Nelson N, Rosenthal R, Rosnow R L 1986 Interpretation of significance levels and effect sizes by psychological researchers. American Psychologist 41: 1299–301

- Neuliep J W (ed.) 1991 Replication Research in the Social Sciences. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Pearson K 1902 On the mathematical theory of errors of judgement with special reference to the personal equation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 198: 235–99

- Rosenthal R 1976 Experimenter Effects in Behavioral Research, enlarged edn. Irvington Publishers, Halsted Press Division of Wiley, New York

- Rosenthal R 1991 Meta-Analytic Procedures For Social Re- search, rev. edn. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow R L 1969 Artifact in Behavioral Research. Academic Press, New York

- Rosnow R L, Rosenthal R 1997 People Studying People: Artifacts and Ethics in Behavioral Research. Freeman, New York