Sample Valdimir Orlando Key Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of political science research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Biographical Summary

Valdimir Orlando Key, Jr. was born in Austin, Texas on 13 March 1908. He spent his childhood in the very small West Texas town of Lamesa, later obtaining a BA from the University of Texas at Austin in 1929, and an MA degree at the same institution in 1930. V. O. Key, Jr. then moved to the University of Chicago—then perhaps the premier institution for studying American politics in the United States—and received his doctorate there in 1934. His early professional years were devoted to teaching and, later, to work in Washington for the Social Science Research Council and, subsequently, as part of the technical staff of the National Resources Planning Board during the heyday of the New Deal. Further Washington experience came his way during World War II with a three-year stint at the US Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget). His academic career took him first to Johns Hopkins University and thence to Yale and Harvard Universities, the latter from 1951 until his untimely death in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on 4 October 1963. The long-standing illness to which he eventually succumbed did not prevent him from moving to the very front rank of American political scientists of his generation. The reasons for this fame—a reputational survey of 1965 by A. Somit and J. Tanenhaus placed him then in a clear first position—will be concisely discussed below.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Scientific Contribution

As a Southerner, and at a time when the South was far more a region apart from the rest of the American polity than it is now, Key proved the ideal scholar to provide a comprehensive description and analysis of the South’s apartheid political order, and its massive influence on national politics, very shortly before its demise. This study, Southern Politics in State and Nation (1949), provided a detailed portrait of politics in each on the eleven former Confederate States at the time of writing, as well as analyses of the region’s influence on congressional politics; and—an important contribution in its own right—an extended summary statement on the nature and consequences of one-party systems for the representation of public opinion through elections. The craftsmanship is meticulous and innovative, with a mixture of ‘thick description’ of persons and forces at work based on extensive interviewing, along with the skilful deployment of charts and maps based upon aggregate returns from referenda and primary and general-election returns. More than half a century later, Southern Politics still repays the reader’s attention.

Quite a lot of Key’s basic approaches to the study of American politics, and his personal value commitments, can be found in these pages. First, and obviously, lies the exceptional historic and contemporary importance of ‘sectionalism’ (major regional differences based on economy, political subculture and experience) in the study of American politics. This point is worth stressing, since with the advent of national scientific surveys of American voters and their behavior in and after the 1960s, this dimension strikingly faded from view in Americanist political science for a protracted period. Secondly, Southern Politics underscored the importance of history and historical experience in shaping the confines of today’s electoral politics. It is thus perfectly appropriate to view Tennessee politics in the 1940s (and later) in light of the polar oppositions that were displayed in a June 1861 referendum on the state’s secession from the Union. This concern to cite present reality in its developmental context was also, however, to run counter to mainstream preoccupations within political science, as the quest for ‘scientific regularities’ variously led to embracing concepts and models derived from social psychology or economics coming to the fore.

Finally, Key’s democratic value commitments, which informed his entire published output across his professional lifetime, are presented in clear view in this magisterial work. Several points about how these views were expressed deserve mention here. Key made no pretension to ‘grand theory,’ and imported no elaborate conceptual schemes from great Europeans such as Marx or Weber. Like many in his and a somewhat earlier generation of American political scientists, his intellectual focus was American to the core, and concentrated on the gap between the democratic promise embedded in the national political culture on one hand, and real-world antidemocratic practices and realities on the other. These latter obviously abounded in the Southern politics he studied, and this gap represented the chief analytic problematic of his lifetime. As he demonstrated in great detail, in the kind of disorganized and exclusionist politics of his South the have-mores profited and the have-lesses lost out as a matter of empirical fact.

At the same time, Key’s was a mind which was strikingly subtle and nuanced. Not for him were the sledgehammer blows of Beard (1913), or other notable writers in the American Progressive tradition. Rather, he very carefully spelled out the structure of a given state of political affairs, equally carefully pointed out the vastness of the gap between ideals and empirical reality, and invited his readers to reflect on this gap and how it might be overcome. He was an optimist about the extent this could be accomplished in time—as scholars shaped by the political crises of the 1960s and 1970s often were not. Thus, his hopes for his native region rested to a significant degree on the longer-term effects of industrialization and urbanization on its society and politics. In retrospect, these hopes were to be realized, though only in the context—he was no prophet, after all—of a massive federal intervention in the 1960s, the ‘Second Reconstruction,’ fuelled by the civil-rights revolution; and, not least, by the USA’s foreign-policy requirements in a postcolonial world.

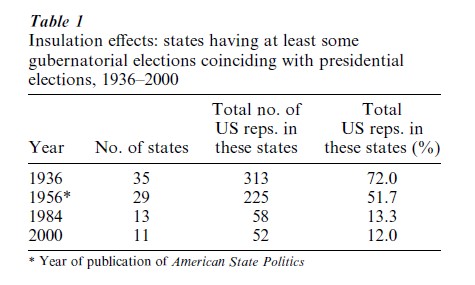

His later major studies displayed his awareness that there were other impediments to the realization of his ideal, the expansion of the electorate’s effective role in politics through the instrument of party competition and political choice. In American State Politics (1956), Key devoted his attention to several of these impediments: the impact of direct primaries and other regulations of party activities on party organization, including the multiplication of uncontested seats in legislative bodies; what he calls the ‘lottery of the long ballot,’ i.e., the separate election of a wide range of state office-holders; and the shifting of major state elections away from coincidence with presidential elections and ‘national tides’ to off years, where, incidentally, voter turnout is nearly always substantially smaller than in presidential years. Key was clearly concerned about the implications of such developments for the integrity of parties as vehicles for individual and collective choice at elections. As Table 1 below shows on just one of these dimensions, his forebodings have been more than amply realized in the long generation since his death.

In his last years, V. O. Key increasingly devoted his attention to the challenges he saw in the development of survey research, both academic and applied. This was to issue in two works, Public Opinion and American Democracy (1961) and—posthumously—The Responsible Electorate (1966), and a number of articles where criticism was perhaps more pointed. He was vigorously opposed to political-science approaches that appeared to eliminate politics from their analytic schemes. He was alarmed by the potential for manipulating the public that was already (if by today’s standards dimly) visible in applied ‘market research’ by candidates and their media and polling staffs. For, in his view, public opinion ultimately was an ‘echo chamber’; and the quality of its output was heavily dependent upon the input provided by political elites and their consultants. Finally, he was convinced that the survey-research portrait of voters as in the main know-nothings (or know-very-littles) drastically underestimated voters’ practical political intelligence and capacity for purposive, rational pursuit of political choice in accordance with their interests. On one major point raised in The Responsible Electorate—the distinction between interelection ‘switchers’ and self-identified partisan independents—his view was later to receive substantial confirmation in a 1981 study of panel surveys by Morris Fiorina (1981). In any event, Key’s last work made its own real contribution to the subsequent explosion of ‘issue-voting’ studies and, eventually, to a much more sophisticated and politically-centered survey-research enterprise.

3. Assessment Of Key’s Professional Impact And Current Importance

As the consummate professional that he was, V. O. Key devoted himself to the well-being and improvement of the political-science profession in countless ways. One example, at a time when statistical knowledge within the profession was still pretty much at a primitive level, was his little 1954 volume, A Primer of Statistics for Political Scientists. Another was his textbook, Politics, Parties and Pressure Groups (Crowell, NY, 1942–1964), which was far the best in its field and extended his teaching to generations of students. He sought to expand the frontiers of knowledge, not only through these and other works, but through myriad contacts with his peers and service to such organizations as the Social Science Research Council and the American Political Science Association.

It may be said that, for two decades or so after his death, Key remained more revered than followed by the political-science mainstream. His was always a sterling example of outstanding craftsmanship in specifying and executing important research projects that provided new insights into the American electoral process; of an enormous mastery of the data of American politics past and present; and a most exceptional capacity to break new ground by using it in novel ways. At the same time, regionalism and history largely fell out of mainstream concerns; his older South rapidly became, or seemed to become, a museum piece; and for a long time, analysis of aggregate election data seemed to be under W. S. Robinson’s 1950 ban on the uses of ecological correlation. Since then, as problematics and professional interests have shifted somewhat, regionalism and historical depth in the explanation of current states of affairs have seen a notable comeback, and a whole field, American Political Development, has emerged into view. At the same time, ecological regression has emerged as a valuable estimation technique for analyzing voter transitions, e.g., during the critical realignment of the 1850s.

In a real sense, Key’s work is more significant today than it seemed to be for some years after his death. Nowhere is this more true than in one major area of research by political scientists and historians alike: the study of critical realignment as a major change process across the span of American electoral, and more broadly political, history. As of 1991 (the last formal count), more than 500 books and articles had been devoted to this subject. While some historians had recognized qualitatively the exceptional turning-point significance of such elections as 1800, 1828, 1860, 1896, and 1932. Key was the first to provide an examination of this as an empirically specifiable problem in his truly seminal 1955 article, ‘A theory of critical elections’ (1955). It is noteworthy that Key never saw fit to explore the subject further, and one can doubt that he would find the elaboration of models in this field always to his taste. But his was the path-breaking innovation that truly founded a vast research enterprise that is still underway, and has also attracted the attention of non-American researchers as well (Pierre Martin, 2000).

Bibliography:

- Bensel R F 1980 Sectionalism and American Political Development. Madison, WI

- Cummings M C (eds.) 1988 V. O. Key, Jr. and the Study of American Politics. Washington

- Fiorina M P 1981 Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven, CT

- Gienapp W E 1987 The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. New York

- Key V O 1949 Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knopf, New York

- Key V O 1955 A theory of critical elections. Journal of Politics. 17: 3–18

- Key V O 1956 American State Politics. New York

- Key V O 1959 Secular realignment and the party system. Journal of Politics. 21: 198–210

- Key V O, Munger F 1959 Social determinism and electoral decision: The case of Indiana. In: Burdick E, Brodbeck A (eds.) American Voting Behavior. Free Press, Glencoe, IL, pp. 281–99

- Key V O 1961 Public Opinion and American Democracy. New York

- Key V O 1961 Public opinion and the decay of democracy. Virginia Quarterly. Re . 37: 481–94

- Key V O 1966 Cummings M C (ed.) The Responsible Electorate. American Political Science Association, Cambridge, MA

- Kleppner P 1987 In Appendix: Realignment theory after Key. Change and Continuity in Electoral Politics, 1893–1928. Westport, CT, pp. 239–50

- Martin P 2000 Comprendre les Evolutions electorales: La theorie des realignements revisitee. Paris

- Natchez P 1985 Images of Voting Visions of Democracy. New York