Sample Access To Justice Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of political science research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

History and political theory both underscore the fundamental importance of providing equal access to justice for all citizens no matter what their economic and social status. It was promised to the subjects of emperors and kings long before those subjects began to even dream of the possibility of governing themselves. Then democratic theory, especially the social contract theory so influential with the founders of democracies in Europe and North America, emphasized that no man would surrender his natural right to resolve disputes through force unless government provided a forum to resolve those disputes where all citizens, rich and poor, had an equal chance. Thus, it is no surprise that constitutions of nearly every democracy guarantee their citizens ‘due process’ or ‘fair hearings’ and ‘equal protection of the laws’ or ‘equality before the law’ (Johnson 2000).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Despite these solemn guarantees, however, for most democratic nations it was well into the twentieth century before governments became serious about offering their lower income citizens equal access to justice. Progress has been uneven, with some countries forging far ahead of others. As of the beginning of the twenty-first century, this has become a field of study for political scientists, sociologists, historians, and legal scholars—seeking to analyze the problems, to devise solutions, to evaluate experimental approaches, to comprehend the political opposition to this goal, and to measure the progress.

1. An Overview Of Access To Justice Strategies

The study of access to justice issues in modern societies begins with an appreciation of the essential role lawyers play in the regular civil courts in every industrial society. In these societies, courts place most of the burden on the parties to investigate the facts, find the applicable law and present the case to the neutral, passive decision-makers—the judges or juries—supplied by the government. This is a heavy, often expensive burden the private parties must discharge and one typically requiring the expertise of lawyers. As a result of this division of responsibility between the government-funded courts and the private litigants, the latter bear most of the cost of the dispute resolution function as carried out in the courts of most modern nations.

This research paper analyzes how modern nations seek to supply counsel to those unable to afford their own, and also how some nations have sought to restructure the dispute resolution function to reduce the need for counsel. Three basic strategies are covered: (a) providing government-funded lawyers to disputants who are unable to afford their own legal counsel (II); (b) providing incentives to encourage private lawyers to represent people unable to afford to pay legal fees but without using government funds (III); and (c) providing dispute resolution forums where disputants can participate fairly without the assistance of a lawyer (IV).

2. Increasing Access To Justice By Providing Government-Paid Lawyers To Disputants Unable To Afford Their Own Legal Counsel

Empirical studies conducted in the USA support the hypothesis that litigants who lack lawyers are severely disadvantaged in the courts, at least as those courts operate at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Galanter 1974). Debtors sued in collection cases who were represented by counsel had a six times better chance of winning than those who defended themselves. A study of unrepresented litigants who brought suit in the Washington, DC courts showed they suffered dismissal at the early stages of the proceedings and not one succeeded in even getting to trial. Also, low-income tenants representing themselves before New York’s housing courts suffered eviction in almost every case while 90 percent of those represented by lawyers were saved from that fate.

Most governments did not require empirical research to reach the conclusion that their lower income citizens required free counsel if they were to enjoy effective access to justice in the regular courts. But the level of commitment to equal justice for all citizens and the willingness to fund the lawyers necessary to that goal vary greatly from nation to nation. Nonetheless, there was a trend toward greater access backed by larger government investments during the second half of the twentieth century in nearly all industrial democracies.

However, the legal status of the right to counsel in the regular courts is far different in the USA than elsewhere in Western democracies. While nearly all European and Commonwealth nations have enacted a broad statutory right to counsel in civil cases, as well as criminal cases, neither the federal nor any state government has done so in the USA. England’s first such statute was enacted in 1495, France in 1852, Germany in 1877, the rest of Northern Europe in the early twentieth century, Italy in 1923, and most Canadian provinces and Commonwealth countries in the 1960s and early 1970s. In these countries, statutes guarantee low-income people that the government will supply them with a lawyer in any case where they qualify financially for such assistance, although they typically require the litigant’s position to have some merit as well. In the past, most countries did not compensate the lawyers appointed to represent needy litigants but expected them to representation on a pro bono basis (Cappelletti et al. 1975). But over the course of the twentieth century more and more of the industrial democracies began to pay the lawyers serving poor people with government funds until by the end of the century a majority of European nations and all of the Commonwealth countries have chosen to do so (Johnson 2000).

Europe and the USA also have gone along different routes in recognizing a ‘constitutional’ right to counsel for indigent litigants. The courts on both continents have declared a constitutional right to counsel in criminal cases. But despite interpreting nearly identical constitutional language, the US Supreme Court and the European Court on Human Rights have reached opposite conclusions on the right to counsel in civil cases. In 1979, the European Court ruled the ‘fair hearing’ guarantee found in the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms required member governments to supply free counsel to indigent civil litigants (Airey vs. Ireland 1979). Two years later, however, in a five-four decision the US Supreme Court held the constitutional guarantee of ‘due process’ did not require the provision of free counsel to civil litigants in the USA (Lassiter vs. North Carolina 1981). Switzerland, although not part of the European Community, anticipated the decision of the European Court on Human Rights over 40 years earlier when in 1937 the Swiss Supreme Court held that nation’s constitutional guarantee that ‘All Swiss are equal before the law’ required government to provide free lawyers to those Swiss citizens who were too poor to hire their own (Judgment of Oct. 18, 1937, O’Brien 1967).

Lacking either a constitutional or statutory guarantee, poor people in the USA and many other countries around the world have legal assistance with their civil problems only if they can get help from a limited number of lawyers supplied through private or legislative charity (Zemans 1979). Indeed private charity was the only source of legal counsel for the poor during most of US history. It took the ‘War on Poverty’ declared in 1965 to create even a minimal level of government funding of legal services for the poor in civil cases (Johnson 1978).

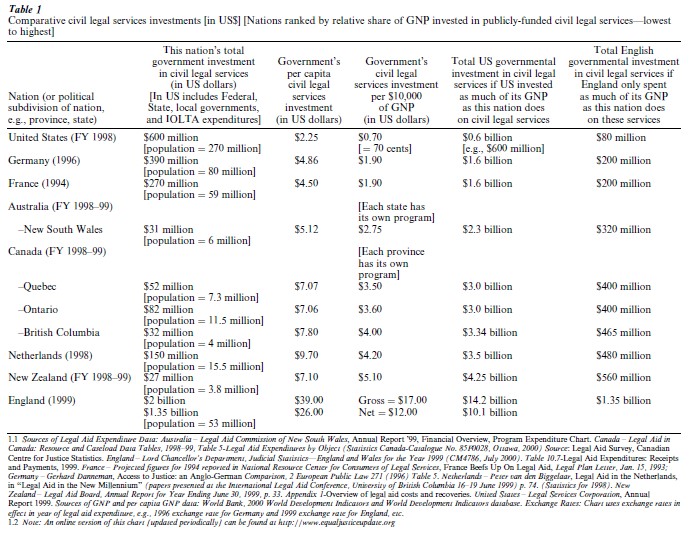

As might be expected, comparative research documents that a statutory or constitutional right to counsel usually leads to a much higher financial commitment to government-paid lawyers for lower income citizens. Table 1 lists several industrial democracies in Europe, North America, and Oceania. The table first compares their total and per capita investments in government-funded civil legal services for those unable to afford lawyers. But the more salient comparison takes account of the relative prosperity of these different countries and reflects how much of a nation’s gross national product its government commits to insuring access to justice for its lower income citizens (as measured by legal services investment per $10,000 of per capita GNP). Finally, the last two columns of the table illustrate what the total budget would be for two countries—England and the USA— were their investments the same per GNP as the other nations portrayed in this study. (These two nations are chosen because they represent the most generously funded (England) and least generously funded (USA) civil legal services programs included in these comparisons.)

Nations also differ in how they deliver their government-subsidized legal services. There are three common models: compensated private counsel, salaried staff attorney, and mixed systems.

Under the compensated private counsel model private lawyers represent lower-income people just as they would paying clients. But when serving those lowincome clients the lawyers submit their bills to the government. The low-income clients, in turn, can usually choose any lawyer who has expressed a willingness to participate in the government program. This is the predominate delivery system in most countries, including England, the largest nations of continental Europe, and the Commonwealth countries.

Under the salaried staff model the government establishes separate legal aid offices, often in ‘clinics’ or ‘neighborhood law offices’ in close proximity to concentrations of low-income people. The offices are staffed with salaried lawyers, usually employed fulltime. When poor people have legal problems they bring them to one of these offices and are represented by these salaried lawyers. The USA is the largest country that primarily relies on this delivery model.

A number of empirical studies have evaluated the costs and benefits of compensated private counsel vs. salaried staff delivery systems. Most comparisons suggest salaried staff programs deliver services at lower cost per case (Currie 2000). Both models score high on client satisfaction, but a substantial percentage also place a high value on the ability to choose their own lawyer—a feature of the compensated private counsel model. At the same time, salaried offices are better able to address community issues faced by the residents of low-income areas (Cappelletti et al. 1975).

Partly in response to the results of these studies and also in order to reduce program costs, several nations have moved to a mixed system that attempts to combine the virtues of the other two. Some of these mixed systems, such as those in Quebec, Canada and Sweden, adopt a ‘client option’ approach, allowing clients to choose between salaried staff lawyers and compensated private attorneys to represent them in a given case. Others, such as those in Ontario and British Columbia, divide legal problems between the two systems on a subject matter basis—typically with clients required to take all ‘poverty law’ cases to salaried attorney offices and the more traditional legal problems such as divorce to compensated private counsel.

Some countries using the compensated private counsel model to implement a right to counsel have experienced ever-expanding legal aid budgets. These budgetary considerations have led some governments, most notably in England, to begin exploring modifications calculated to reduce costs. These measures include ‘franchising’ where the government signs contracts with certain private lawyers and law firms to provide services at reduced fees. They also include variations of a ‘capitation’ approach where lawyers agree to handle all the legal problems generated by the entire low-income population in a defined geographic area for a fixed per capita sum (Moorhead 1998). British Columbia in Canada uses a form of ‘managed care’ common in some health delivery systems in which staff members closely monitor each litigation investment decision a compensated private lawyers might make during the course of a representing a poor person. In 1999 and 2000, England introduced several cost-control measures as part of a major overhaul of legal aid and the entire civil litigation process in that country (Regan et al. 1999).

3. Arrangements Which Encourage Or Require Private Attorneys To Represent Lower Income People Without A Government Subsidy

In some nations, government-subsidized lawyers coexist with fee arrangements that encourage private attorneys to represent lower income clients without government funding in certain categories of cases. The most common of these are: (a) contingent fees, (b) conditional fees, and (c) court-awarded fees. In addition to these economic incentives, in many countries—especially those like the USA where government-funded legal services are in short supply—public policies encourage or require private lawyers to devote some of their time to the representation of poor people on a pro bono (uncompensated) basis (see Sect. 3.4).

3.1 Contingent Fees

The USA is almost unique in allowing lawyers to represent clients on a ‘contingent fee’ basis. Under fee contracts allowing them a percentage (typically 33 to 40 percent, but sometimes lower for early settlements and higher for trials) of the client’s recovery, lawyers agree to assume the risk of failure, not charging any fee if they lose. Thousands of the poorest citizens are represented each year in cases where they are suing for a substantial sum of money and have a good chance of winning. At the same time, the contingent fee system offers no help to low-income people who are defendants, or who are plaintiffs in the many categories of legal disputes that do not involve monetary stakes or where the potential financial recovery is too modest to cover the risk of loss (Regan et al. 1999).

The contingent fee system is not without its critics. Some charge the fee percentages are too generous to lawyers, leaving their clients with less than full compensation for their injuries. Others, however, respond that if the percentages are set too low, lawyers will not find it economically feasible to take cases offering only modest potential recoveries or posing a significant risk of loss. Without the bonus of substantial fees when they win, contingent fee lawyers cannot afford to take riskier or smaller cases and thus can contribute less to increasing access for the low-income population (Regan et al. 1999).

Other studies have applied economic analysis to suggest the typical contingent fee structure places lawyers and their clients in a conflict situation. The lawyers maximize their profits when they get a decent recovery with a minimal investment of time while the client is best served by the largest possible recovery no matter how much time and effort the lawyer must expend. As a result, contingent fee lawyers may be inclined to settle too early and for too little, from the client’s perspective. A recent empirical study, however, suggests contingent fee lawyers may come closer to maximizing their clients’ returns than economic analysis predicted (Kritzer 1998a).

3.2 Conditional Fees

Most countries, other than the USA, use a ‘loser pays’ rule in allocating legal fees. That is, losing litigants pay not only their own lawyers but are required to pay at least a ‘reasonable fee’ to the winners’ lawyers. A few nations, Ireland and at the beginning of the twenty-first century England, modify this rule in a way that may allow lawyers to serve low-income clients without a government subsidy in some cases.

In 1995, England introduced a modified form of the ‘conditional fee’ model, one that as of 2000 applies to nearly all civil litigation involving monetary stakes no matter the economic means of the parties. Under this model lawyers do not charge their clients a fee if they lose, but can charge an ‘uplift’ of up to 100 percent, in effect doubling their fee, if they win, with that ‘uplift’ payable out of the clients’ monetary recovery. However, the total amount of the fee including the ‘uplift’ cannot exceed 25 percent of that recovery. Should they lose, clients are not relieved of their obligation to pay the other side’s fees. But, if they can afford it, they can purchase insurance to cover this risk.

The UK government expects the ‘conditional fee’ system to supplant legal aid for the claimant’s side of most cases offering the prospect of a monetary recovery. Critics point out the prospects of success must be unusually favorable before lawyers will be willing to provide representation under a ‘conditional fee’ system. They will not get a fee from either side if they lose and the ‘reasonable fee’ they do receive will ordinarily be less generous than the 33 to 50 percent of the judgment that contingent fee lawyers typically earn when they win at trial (Moorhead 2000).

3.3 Court-Awarded Fees

Many jurisdictions in the USA depart from the general ‘American’ rule and shift fees to the losing party in certain categories of cases: (a) Statutory fee-shifting— in lawsuits under statutes specifically authorizing fee-shifting in favor of private parties whose cases enforce the public policies embodied in those statutes; (2) Public interest fee-shifting—in lawsuits where the court, rather than the legislature, determines that the public interest will be promoted by awarding winning litigants the bonus of requiring the loser to pay their legal fees.

Both statutory fee-shifting and public interest fee-shifting offer an alternative source of funding for those unable to afford their own counsel. They are especially important in major litigation not offering the possibility of a substantial monetary recovery, such as those seeking injunctive relief ordering the government or some other institutional defendant to change its policies in the future (Cappelletti et al. 1978–79). Where a case satisfies one of these standards, these fee awards can be more generous than either contingent or conditional fees, and frequently are. The court is typically not limited by the size of the winning party’s economic recovery, which often is nothing, but can award winning lawyers their regular full hourly fees for the time they spent on the case. Beyond that, they can apply a ‘multiplier,’ doubling or tripling the lawyers’ fee in order to recognize the riskiness, complexity, or significance of a particular piece of litigation (Regan et al. 1999).

3.4 Voluntary And Mandatory Pro Bono Legal Services

As mentioned earlier, most European countries originally implemented the statutory right to counsel by appointing lawyers to provide free legal representation to poor people without compensation—a form of mandatory pro bono services. During the twentieth century most of these nations found this approach unsatisfactory and shifted to a system that compensated the lawyers representing the poor (Huls 1994, Johnson 1994), although a few, like Italy, still depend on drafting lawyers to provide legal aid (Cappelletti et al. 1975).

Voluntary pro bono services depend entirely on the charitable impulses of the private legal profession. Faced with a shortage of government-funded legal aid the USA in the last decades of the twentieth century has attempted to encourage more private lawyers to volunteer time to represent the poor. Many states and cities have organized pro bono programs supervised by staff. Others require private lawyers to report annually on the hours devoted to pro bono services. A national program issued a ‘pro bono challenge’ to the 500 largest law firms, asking them to commit 3 to 5 percent of the firm’s billable hours to pro bono representation of the poor—and had mixed results. Some other nations—Sweden and Australia, among them—also have begun to look to pro bono services to fill some of the gaps created by reductions in government legal aid budgets (Regan et al. 1999).

There is serious question, however, whether societies can expect pro bono legal services to play more than a limited, supplementary role in the delivery of legal representation to low-income people. Is there any more reason to expect lawyers to supply enough services on a pro bono basis to meet the low-income population’s total need for legal services than to expect medical doctors and hospitals to supply enough of their services pro bono to replace the present government-funded health care systems for the poor? —e.g., Medicare and Medicaid in the USA, the National Health Service in the UK etc.

4. Increasing Access To Justice Without Supplying Free Lawyers, Government Paid Or Otherwise

Professional lawyers appear essential to fair proceedings in the regular courts of most modern countries, as the European Court on Human Rights held in Airey vs. Ireland (discussed in Sect. 2). The legal rules governing the decisions are complex, the procedures intricate, and investigatory techniques difficult to master. For all these reasons, unrepresented parties seldom have a chance for a ‘fair hearing’ in the regular courts.

Yet the European Court on Human Rights also recognized it may be possible for governments to create forums—for some cases at least—where the assistance of lawyers is not crucial and thus effective access to justice can be achieved without providing free counsel to lower income disputants (Airey vs. Ireland 1979). It is possible to identify four approaches that various countries have tried, alone or in combination, in an attempt to de-professionalize dispute resolution: (a) simplified forums; (b) law simplification; (c) technological substitutes for legal expertise; and (d) the use of less expensive, non-lawyer advocates.

4.1 Simplified Forums

For simpler disputes it may be feasible to construct simpler dispute resolution processes. Early in the twentieth century, several countries started ‘small claims courts’ to hear disputes involving minor stakes. Using simple procedures and expecting the judges to take a more active role in developing the facts, these courts were designed to function well without lawyers. Some criticize small claims courts for pitting poor people against lawyers hired by institutions such as credit companies, landlords, and businesses. A few jurisdictions responded by banning lawyers entirely from these courts. Studies of small claims courts have arrived at mixed findings about their fairness to individual litigants, especially in cases involving institutional opponents (Yngvesson et al. 1979).

Some jurisdictions also have created specialized courts roughly based on the small claims court model to handle certain narrow categories of cases (housing courts, labor courts, social welfare courts, and the like) with the expectation that their simplified processes would allow many disputants to represent themselves. Once again, the results are mixed (Cappelletti et al. 1978–79).

In addition to simplified courts within the court system itself, some jurisdictions have created administrative bodies empowered to resolve certain categories of disputes. For example, in England, ‘tribunals’ composed of part-time volunteers decide most disputes arising out of public housing and other government benefit programs. In British Columbia, Canada, an agency called the ‘Rentalsman’ determines most landlord–tenant disputes. In many jurisdictions administrative hearings decide whether a worker is entitled to compensation for job-related injuries and how much. Once again, the procedures are simple compared to the regular courts and typically disputants are encouraged to appear without lawyers—and sometimes lawyers are barred entirely (Cappelletti et al. 1978–79).

In recent years, private mediation and arbitration (often called Alternative Dispute Resolution or simply ‘ADR’) have emerged as major alternatives to the regular civil courts, especially in the USA. The primary motive behind the growth of these alternative forums, however, arises not from a desire to increase access to justice for lower income individuals, but to reduce delay and expense for more affluent litigants (Abel 1982).

While private mediation and arbitration have not proved a significant strategy for increasing access to justice when the disputes pit individuals against institutions, they have offered a useful alternative to litigation in disputes between evenly matched individuals (Menkel-Meadow 1999). Some communities in the USA have started neighborhood (or community) dispute resolution centers to help people settle disputes—especially those between family members or neighbors—without resorting to the courts. The services are usually free or require only nominal fees (Singer 1979).

4.2 Simplification Of Substantive Legal Rules Governing Disputes

One of the major reasons people must employ lawyers to represent them is the complexity of the legal rules the judge or jury will apply to decide who wins. Some suggest we can reduce the need for lawyers and thus improve access for lower income disputants by simplifying those rules. In some jurisdictions, for example, legislatures enacted no fault divorce laws and authorized couples to obtain ‘summary divorces’ if they had no children, limited property, and short-term marriages. Presumably, these statutory changes allow most people who qualify for such divorces to do so without a lawyer (Cappelletti et al. 1978–79). In an ever more complex society, however, it is questionable whether simplification of the legal rules will emerge as an important strategy for increasing access to justice in any but very limited circumstances.

4.3 Technological Substitutes For Legal Expertise

Starting in the late 1980s software developers produced a host of computer programs designed to offer average citizens the ability to generate legal documents such as wills and contracts. In the 1990s court systems and others desiring to increase access to justice for lower income individuals began developing programs which use similar technology to generate litigation documents that can be filed in common cases such as landlord–tenant, child custody, and spousal abuse cases. As of 2001, however, there has been no assessment of the issue whether these computer-generated litigation documents help litigants if they lack legal representation when they appear in court.

However, technology, computer technology in particular, may have only begun to transform the dispute resolution process in ways which could improve access for lower income litigants. Conversely, technology may reduce access to justice by increasing still further the cost of the litigation process and compounding the advantages higher income parties already enjoy. In fact, this phenomenon so evident in the health care field, can also be observed in the law. Only the party with considerable resources can afford many of the expensive scientific tests and fancy computer-generated graphics which enhance the chances of victory in the modern court room.

4.4 Use Of Less Expensive, Non-Lawyer Representatives

Some specialized lower-cost forums permit nonlawyers to represent parties appearing before them. Some even rely exclusively on non-lawyer advocates for this role. Presumably the use of these less educated and less expensive personnel enhances access by lowering the cost of representation to the parties or to the government employing the advocates.

A recent study tested the difference between representation by lawyers and representation by lay advocates in these administrative forums. The study suggests only marginal differences in the quality of representation or the results achieved. It says little if anything, however, about the comparative performance in the regular courts or other forums that decide a broader range of disputes requiring advocates possessing a greater body of legal knowledge and skills (Kritzer 1998b).

5. Future Issues In The Movement Toward Equal Access To Justice

The major issues for government-funded legal aid and equal access to justice in the twenty-first century include: (a) whether a ‘globalization of constitutional values’ will lead courts in the USA and elsewhere to join the majority of industrial democracies in recognizing a constitutional right to counsel in civil cases; (b) whether those nations which already have such a right as a matter of statute or constitutional interpretation will develop delivery mechanisms and alternative dispute resolution policies allowing them to guarantee effective access for lower income citizens at politically sustainable levels of public investment; and (c) whether the vital importance of equal access to justice for democratic government and political stability will cause developing countries and former communist nations to institute significant legal aid programs. As it has in the past, social science will have much to contribute not only to the design of these initiatives, but more importantly to their evaluation. The insistence on empirical proof will offer the most effective guarantee that what emerges indeed grants every citizen, irrespective of means, the right to equal justice that democratic societies promise to all.

Bibliography:

- Abel R (ed.) 1982 The politics of informal justice: the American experience, Vol. 1. Comparative Studies (Vol. 2). Academic Press, New York

- Airey . Ireland. Eur. Court H.R. (Ser. A) Judgment of Oct. 1979

- Cappelletti M, Gordley J, Johnson E Jr 1975, 1981 Toward Equal Justice: A Comparative Study of Legal Aid in Modern Societies. Oceana, New York

- Cappelletti M, Bryant G (eds.) 1978–79 Access to Justice. 3 Vols. Giuffre, Milan

- Currie A 2000 Legal aid delivery models in Canada: Past experience and future developments. University of British Columbia Law Review 33: 285

- Galanter M 1974 Why the ‘haves’ come out ahead. Law and Society Review 9: 95

- Huls N 1994 From pro deo practice to a subsidized welfare state provision: Twenty-five years of providing legal services to the poor in the Netherlands. Maryland Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 4: 326

- Johnson E Jr 1978 Justice and Reform: The Formative Years of the American Legal Services Program. Transaction Press, New Brunswick, NJ

- Johnson E Jr 1994 Nordic legal aid. Maryland Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 4: 301

- Johnson E Jr 2000 Equal access to justice: Comparing the United States and other industrial democracies. Fordham International Law Journal 24: 83

- Kritzer H 1998a Contingent-fee lawyers and their clients: Settlement expectations and settlement realities. Law and Social Inquiry 23: 795

- Kritzer H 1998b Legal Advocacy: Lawyers and Nonlawyers at Work. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

- Lassiter . North Carolina, 452 US 18 (1981)

- Lawrence S 1990 The Poor in Court: The Legal Services Program and Supreme Court Decision-making. Princeton, Lawrenceville, NJ

- Menkel-Meadow C 1999 Do the ‘haves’ come out ahead in alternative judicial systems? ‘Repeat players’ in ADR. Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution 15: 19

- Moorhead R 1998 Legal aid in the eye of the storm: Rationing, contracting and a new institutionalism. Journal of Law and Society 25: 365

- Moorhead R 2000 Conditional fee agreements, legal aid, and access to justice. University of British Columbia Law Review 23: 471

- O’Brien W 1967 Why not appoint counsel in civil cases: The Swiss approach. Ohio State Law Review 28: 1

- Regan F, Paterson A, Goriely T, Fleming D (eds.) 1999 The Transformation of Legal Aid: Comparative and Historical Studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Schefergegen Appenzell A.R.H. Regierungsrat, Judgment of Oct. 8, 1937, BGE 63 Ia 209 (1937)

- Singer L 1979 Nonjudicial dispute resolution mechanisms: The effects on justice for the poor. Clearinghouse Review 13: 569

- Yngvesson B, Hennessey P 1975 Small claims, complex disputes: A review of the small claims literature. Law and Society Review 9: 219

- Zemans F 1979 Perspectives on Legal Aid. Frances Pinter, London