Sample International Labor Organizations Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of political science research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

You shall not abuse a needy and destitute laborer, whether a fellow countryman or a stranger in one of the communities of your land. You must pay him his wages on the same day, before the sun sets, for he is needy and urgently depends on it; else he will cry out to the Lord against you, and you will incur guilt. Deuteronomy, ch. 24, v. 14, 15.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Rapid globalization succeeded the Cold War as the axis around which international labor organizations worked at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The International Labor Organization (ILO), under vigorous new leadership, sought a place at the table where the intellectual and policy architecture of the global economy is determined. The International Confederation of Trade Unions (ICFTU) and the international trade secretariats (ITSs) strengthened ties with national labor organizations to counter the power of multinational corporations that reshape the international division of labor, to influence the international institutions that provide credit to national governments, and to share in making the rules that govern trade and international investment. These bodies historically have been subordinate to the national institutions they represent; globalization may change this balance.

1. Historical Background

The nineteenth-century industrial revolution evoked a strong response as exploitation and social injustice grew, first in the UK and then in Europe and North America. The communitarian aspirations of Robert Owen and the reformist fervor of the Chartists was followed by more specifically class-based organizing in the 1840s and 1850s, culminating in the First International, the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA), founded in London in 1864, in which Karl Marx played a leading role. As strikes grew in number and fervor, efforts to prevent employers from importing ‘blackleg’ workers to break strikes strengthened international connections in Europe and the UK.

Local unions began to grow in numbers and geographic scope, reflecting the expansion of markets. Closely linked at first to socialist organizations, they developed more pragmatic activities in response to problems in the workplace. In most of Europe, the unions were created by, and were close to, socialist or social democratic movements; in the UK, by contrast, the Trades Union Congress preceded and created its political arm, the Parliamentary Labour Party.

The Chicago Haymarket affair and the prosecution of anarchists accused of the bombing strengthened efforts to build international solidarity. Major influence in the Second International, largely stimulated by Haymarket, went to socialist and social democratic parties in Germany, Austria, and Sweden, all of which sponsored newspapers, housing, theater, music, and other activities for the working class and the public. It fell victim to World War I (Windmuller 1979, pp. 3–4).

2. The International Trade Secretariats (ITSs)

These institutions link unions representing workers in cognate skills or sectors. The first was the Federation of Boot and Shoe Operatives, founded in1889 in Paris at the time of the first congress of the new Socialist International. By 1914, there were almost 30; they included the International Transport Federation, founded in London in 1896 by the London dockworkers, the first ITS to include semi-skilled and unskilled workers. In later years, mergers and closures reduced this number to 14 at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Except for the US mineworkers union, these were almost completely European bodies before World War I (Windmuller 1979, pp. 3–4).

Efforts to build broader international solidarity among national labor bodies separate from the socialist international began with a 1901 conference in Copenhagen organized by Scandinavian, Belgian, German, and British union leaders; the next year in Stuttgart they founded what later became the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) (Van Hooten and Van Der Linden 1988, p. 11). It too fell victim to World War I, which largely ended visions of international solidarity; as Eric Hobsbawm wrote (in Van Hooten and Van Der Linden 1988, p. 11):

For socialist leaders the outbreak of war and the collapse of their international in August 1914 were utterly traumatic … The same Welsh miners who both followed revolutionary syndicalist leaders and also poured into the army as volunteers in 1914 brought their coalfield out in a solid strike in 1915, deaf to the accusation that they were being unpatriotic in doing so.

2.1 International Labor Legislation

The International Association for Labor Legislation was proposed in 1897 and formed in 1901, a ‘direct forerunner of the I.L.O.’ (Morse 1969, p. 7). Like its counterparts, the International Association on Unemployment, and the International Association for Social Progress, it developed model legislation designed to help governments create effective programs. Here too, World War I ended this work, though some labor unions continued to meet during the war years.

3. Between The Wars

By 1917 the American Federation of Labor (AFL), under Samuel Gompers’ leadership, had established itself as the dominant national labor organization. It consisted almost completely of skill-based craft unions in a loose confederation. Efforts to organize the unskilled and semi-skilled by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had been crushed by employers, unchallenged or actively supported by government at all levels. The AFL had initially resisted involvement in the war, but by 1917 it was actively involved. This brought Gompers closer to the national centers of power. In 1917 he arranged for President Woodrow Wilson to address the AFL annual convention, the first US president to do so (Larsen 1975, pp. 77–106).

In September 1918, Gompers attended the Interallied Labor Conference in London; he played a major role and was successful in sponsoring a motion in favor of full surrender by the Central Powers, against the views of some European unionists. Gompers was elected chair of the international labor commission organized to recommend measures to deal with labor questions in the peace treaty.

3.1 The AFL And Versailles

A socialist in his early years Gompers later argued that trade unions should focus on the needs of their members and eschew any broader ideological views; he once said, ‘I have no quarrel with Socialists, but I have no use for their proposals.’ He insisted that the commission he chaired meet in Paris, to be close to the treaty discussions, and as he said, it ‘should not be held any place except Paris if we wanted to protect our deliberations from a Bolshevik stampede (Gompers 1957, p. 302).

The conference produced the basic design and purpose of the ILO, and a clause on labor rights that was included in the Versailles treaty. Efforts to revive the IFTU were less successful; the new Soviet unions wanted their own structure, as did union bodies with Catholic or Protestant denominational identities. Gompers withdrew the AFL because he saw no way to coexist with the Soviets, and because he insisted on complete autonomy for each national union body. He never wavered from the view that unions’ only legitimate concern was the well-being of workers through collective bargaining.

4. The ILO Between The Wars

British delegates, impressed by the achievements of a tripartite structure of cooperation among business, labor and government in the war effort, took the initiative in incorporating tripartism into the governance of the ILO. Gompers chaired the 1919 founding conference in Washington. The Senate’s refusal to ratify the Versailles treaty made it impossible, or impolitic, to propose US membership; Republican presidents in the 1920s shunned both the League of Nations and its agency, the ILO.

4.1 Early ILO History

Even without US membership, the ILO was able to move quickly and effectively. It adopted 16 conventions and 18 recommendations in its early years, dealing with the 8-hour day and the 48-hour week, protection of women and young people at work, maternity protection, and protection of maritime and agricultural workers. (Conventions are debated in two successive annual conferences before they can be adopted. When ratified by states they have the force of international law. Recommendations carry less weight.) By 1939 67 conventions and 66 recommendations had been adopted, and the tripartite governance system was firmly in place. The International Court of Justice affirmed the ILO’s jurisdiction in cases brought by national governments. The ILO’s program of research, utilizing experts and investigating in the field, had built a reputation for quality. As governments began to experience the potential effects of conventions, the pace of adoption slowed, testimony to the ILO’s effectiveness, Membership expanded beyond the core of advanced economies to include nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Morse 1969, pp. 4–23, Ghebali 1989, pp. 9–14).

4.2 US Affiliation

Reversing earlier policies, the AFL supported US membership at its conventions in 1932 and 1933. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, took the lead in persuading President Roosevelt that the USA should join, and in lobbying both houses of Congress, arguing that ILO expertise could help in the design of social welfare and labor legislation, as indeed it did (Ostrower 1975, Martin 1976, pp. 427–30). The Soviet Union also affiliated in 1934, but ceased to send delegates to the annual conference after 1937, while the USA continued to participate; John G. Winant served as Assistant Director from 1935 to 1938, and as the first American Director General between 1939 and 1941.

5. World War II, The Philadelphia Declaration And The Cold War

Exiled to Canada during the war, the ILO convened in Philadelphia in 1994, its twenty-fifth anniversary. President Roosevelt sent a warm message, and held a reception after the conference ended. The ‘Philadelphia Declaration’ charted an ambitious course for the ILO in the postwar era. It revised some of the constitutional language, reaffirmed its basic principles, and defined the priorities of social justice and ‘a just share of the fruits of economic progress’ as central to the avoidance of the return of depression and war. These included full employment, the right of workers to collective bargaining, social security protection, access to medical care, protection of women and children, adequate housing and nutrition, and safe and healthy working conditions. Its human rights emphasis anticipated the language of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 (ILO 1944). It emphasized, as ILO leaders continue to do, that the ILO is the only international institution that provides a franchise and governance role to workers and employers.

5.1 Post-War Growth

Between 1949 and 1968, the number of member nations increased from 55 to 118, and the budget grew fivefold; the ILO moved much closer to universal membership. It developed a relationship with the UN Development Program for cooperative work in developing economies. Its World Employment Program adopted in 1968 focused greater attention on the problems of unemployment and underemployment. Its attack on apartheid led to the withdrawal of South Africa in 1966. Its technical and professional reputation grew; it built a reputation as ‘the world’s centre of excellence for research and understanding of labour-related issues’ (Langille 1999). David Morse, who served as Director General from 1948 to 1970, raised the visibility and influence of the ILO in the USA.

6. The Cold War And The Crisis Of International Labor

The USA withdrew from the ILO in 1977, but rejoined in 1980. A crisis of confidence had developed around two issues: the increasing bitter US–Soviet Cold War rivalry, and the international effort to isolate and punish Israel; the ILO was weakened seriously by both.

6.1 AFL And CIO International Competition

Large-scale organization by Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions of masses of unskilled and semi-skilled workers posed a major challenge to the AFL’s historic dominance in labor matters. CIO officials played major roles in the economic war effort, and built close relationships with the Roosevelt administration. The CIO opposed the AFL’s views in international labor affairs and developed its own relationships, building alliances with French and Italian union bodies that were anathema to the AFL’s virulently anti-communist positions.

The AFL’s views were close to those of the intelligence and foreign policy agencies in the postwar government, and the two forged close financial and working relationships. The CIO played an active role in the formation of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), which included Soviet unions and unions close to the Soviets, especially in France and Italy. CIO leaders were not friends of communism; their actions were pragmatic efforts to achieve relative equality in international union matters with the AFL.

The 1947 Marshall Plan proposal completed the rift between the Soviet bloc and most unions of the free world. The CIO supported the Marshall Plan and President Truman’s 1948 election campaign. It withdrew from the WFTU; both the AFL and the CIO participated in the founding of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) in 1949, and were elected to two of the seven vice presidencies (Radosh 1969, pp. 304–47, Reuther 1976, pp. 329–59, 411–27). The AFL–CIO’s Cold War obsessions strained relationships with many ICFTU affiliates and weakened its capacity to respond to changing economic and political challenges; this ended only after new AFL–CIO leaders were elected in 1995.

The effort by the WFTU to control the ITSs raised strong resistance. ITS leaders recognized that the achievement in wartime USA of full employment and rising standards of living for workers provided a viable alternative to the Soviet model that had boasted of its progress during the Great Depression. Their lifelong loyalty to social democratic or socialist principles had earned them the hostility of the communist movement, which they reciprocated, in the 1920s and 1930s. Soviet opposition to the Marshall Plan reinforced their resistance, and their support of a new international body that respected the independence of these long-established institutions. Even in France, where support of the Soviet unions was strong, old divisions reemerged; ‘Force Ouvriere,’ one observer remarks, ‘is a child of France, not of the United States’ (MacShane 1992, p. 277). Konrad Ilg, the longtime secretary of the International Metalworkers Federation (IMF), pointed in 1945 to an ‘iron curtain … behind which developments are taking place about which we know hardly anything (MacShane 1992, p. 15). (This iron curtain image preceded by several months the more famous words of Winston Churcll.) MacShane describes the opposition of the ITSs to the WFTU as the ‘submerged rock that ripped out one of the sides of the WFTU,’ while the Marshall Plan was ‘the more visible reef’ (MacShane 1992, p. 26).

7. The ILO In The Post-Philadelphia Era And The Cold War

Early on, the ILO defined two conventions adopted in1948 and 1949 as basic: No. 87 (freedom of association and the right to organize), and No. 98 (right to collective bargaining). In later years two others were added: No. 29 (elimination of forced or compulsory labor), and No. 111 (elimination of discrimination in employment and choice of occupation). They have acquired a quasi-constitutional standing; even states that have not ratified them are expected as a condition of good standing to honor them, and are subject to scrutiny if they are charged with failure to do so.

Employment issues were highlighted when in 1969— the year the ILO was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize—it launched a multi-year World Employment Program, one of whose products is the annual World Employment Report.

7.1 US Withdrawal And Reaffiliation, 1977–80

Cold War tensions reached a peak with the appointment in 1970 of a Soviet official as Assistant Secretary General, drawing strong US objections. US payments were suspended for a year in protest, then resumed. Admission of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to observer status, over US objections, led to regular attacks on Israel by Arab and other members; the USA argued that these were political in nature, not germane to the ILO’s work, but they continued. US employers objected to the admission of Soviet citizens to the employer group, on the grounds that they were no more than agents of the Soviet state. In 1977, the USA endorsed an ILO study critical of forced labor in the Soviet Union, but it failed to pass—‘the US had asked for a vote of confidence, and none was forthcoming’ (Galenson 1981, p. 65).

The USA filed a letter in 1975 giving 2-year notice of its intention to withdraw. Withdrawal was damaging both financially and politically; the level of interest and awareness of the ILO, even among labor and legal scholars, remains low. The Carter administration concluded that withdrawal had served its purpose, and that US interests would be better served by rejoining, which occurred in 1980. George Meany’s retirement from the AFL–CIO presidency helped.

8. The ILO, The ICFTU, The Trade Secretariats And The Changing Global Economy

The world’s economy and politics were transformed by the end of the Cold War and the large-scale globalization of economic life. Discussion in the ILO resulted in the adoption in 1998 of the ‘ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-Up.’ This followed the 1995

Copenhagen World Summit for Social Development, whose principal organizer, Juan Somavia of Chile, took office in March 1999 as the first ILO Director General coming not from an advanced economy but from ‘the South,’ symbolic of increasing divisions in levels of economic development and well-being.

Under the terms of the Declaration, the ILO was committed to producing annual reports, beginning in 2000, under the rubric of ‘Your Voice At Work,’ focusing on each of the basic rights that form the ILO’s bedrock principles:

2000—ensuring the right of all workers to form and join unions, with similar rights to employers;

2001—elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor;

2002—elimination of child labor; and

2003—elimination of discrimination in employment and choice of occupation.

8.1 New ILO Leadership

In his first year in office the new Director General began to address three major challenges that the ILO faced:

(a) Organizational reform and renewal to ensure that the International Labor Office has identified accurately the major objectives to be addressed, and has the staff and structure needed to address them effectively.

(b) Strengthening relations with international and national labor bodies and other institutions to build more effective cooperation in the shared effort to achieving the right balance between growth and equity, market power and social protection, efficiency and justice for working people.

(c) Participation in the processes by which the global economy defines and effectuates the structure of rules and governance for nations and independent entities, private and public, that wield power and influence, making the ILO, in the words of the Director General, ‘a leading organization of the twenty-first century.’

A comprehensive reorganization of the International Labor Office, around a set of specified goals and priorities, was well under way in 2000. The new structure differs significantly from that which preceded it. (An earlier organizational structure is shown in Ghebali 1989, pp. 164–5.)

An ambitious schedule of conferences, speeches and consultations took the Director General to many parts of the world in his first year. Audiences included the ICFTU world congress in Durban, South Africa; the annual convention of the AFL–CIO; the congress of the European Trade Union Congress (ETUC); the TUC annual conference; the May Day workers’ jubilee in Rome; the UN General Assembly; the World Trade Organization (WTO) ministerial conference; the Organization of African Unity; and the follow-up conference to the Copenhagen World Summit. The schedule continued at the same pace in 2000 and beyond.

The ILO was able to broker discussions involving the Secretary General of the UN, international labor leaders, and international business organizations on the concept of a ‘global compact’ which addresses the central issues of equity and representation that the global economy continues to raise as it restructures economic activity and redefines the international division of labor.

Participation in governance is the most difficult of these objectives. The ILO has consultative status with the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but relations with the WTO remained at the discussion level in 2000.

9. International Unions And The International Economy

Many of the difficulties and challenges that face the ICFTU and the ITSs have long histories. Because economic development occurred at different rates in different countries, inevitably unions were engaged in domestic struggles for recognition, power, and influence. Some national union bodies were the offspring of political parties; others, notably in the USA, developed independently of the parties. Some are focused on national political struggles to protect and advance workers’ rights and interests, while others see the workplace and the employer as the focus of the struggle, with the state serving primarily as rule-maker, not decision-maker. In some countries, union density has consistently been high, while in others it fluctuates. Some have a single national body and a centralized structure, while others confront multiple claims and competition for workers’ support.

In Europe, the ETUC has been successful in developing cross-national forms of cooperative activity and effective collaboration; a shared history, close geographical links, and decades of involvement in the process of economic integration, deregulation of labor markets, and increased cross-national mobility play important enabling roles. Some of the ITSs have developed new leadership and greater ability to organize cooperative activities of mutual support; International Transport Workers was helpful in the US strike by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters against United Parcel Service in 1997, an important milestone in the effort by US unions to restore balance after the erosion in strength that greatly reduced union density and effectiveness after 1980.

Because even the most globally organized multinational corporations operate in countries with governments, unions, political parties, and social movements they are in principle subject to laws that govern labor affairs, social protection, health and safety, environmental integrity, and other subjects of national legislation and attention by the media and the public. Advocates and consumer organizations have been able to expose patterns of exploitation in both underdeveloped and domestic ‘sweatshops.’

10. Conclusions

The power to affect or control the direction of economic and social policies will remain the central issue, and will be determined, as the past shows, by the relative balance of forces with different goals and priorities, and the degree of unity or division among them. For international labor, the objective remains an economic order that protects and promotes the range of human rights embodied in the ILO basic conventions, and a structure of governance and rulemaking that ensures a voice which represents and advocates these rights.

10.1 The ILO

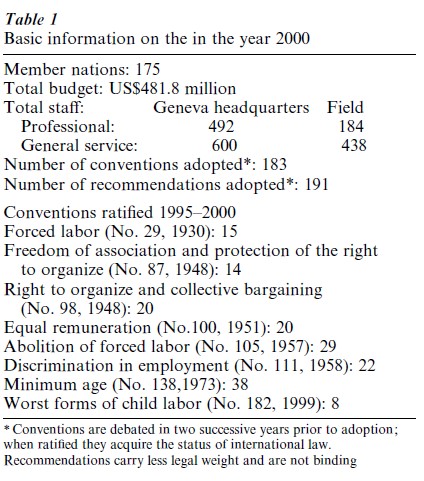

The ILO has built over the decades a rich web of international and national legislation, investigations, and interpretations of its conventions and recommendations. Its role in developing social welfare policies, and standards for the regulation of labor conditions in a wide range of occupations, has helped to build credibility in countries in every area and at different levels of economic, social, and political development. It remains the only international institution where the workers and employers have a voice in decision-making and policy determination. It has survived serious crises that threatened its continuity and viability. (For information on the ILO in the year 2000, see Table 1.)

For its first three decades, the ILO was the sole international voice advocating and defining human rights. In the postwar era others have taken up this role; UN human rights covenants set standards for governments. Codes of conduct are negotiated with individual firms that operate in more than one country. The ILO’s decision-making structure is based on representation by nations in a period when strong economic and demographic forces challenge the ability of national governments to deal with them. The ILO’s efforts to gain a seat at the rule-making table had achieved only limited results at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

10.2 International Trade Union Bodies

The ICFTU and the ITSs were able to move forward after Cold War tensions abated in the last decade of the twentieth century, but they lacked the financial support and organizational linkages needed to engage effectively the corporate and financial interests that came to dominate the international economy in the late twentieth century. International capital deployed a wide range of strategies that continued to build more concentrated corporate power; labor’s inventory is more limited. Use of strikes, boycotts, sharing information, building popular support, use of media, and domestic political work all play a role, but unions remained on the defensive in most areas of the world. Union densities declined and labor-linked political parties shifted toward the right or center. The center of gravity of intellectual work in international economics endorsed the values of markets and competition; progressive views about social welfare, labor markets and industrial relations had lost ground and confidence in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

This had begun to change as the costs and consequences of globalization were examined and doubts raised about the validity of these global paradigms. Large-scale and long-lasting unemployment, increased inequality and poverty, illiteracy, and malnourishment (UNDP 1999) all raise the level of skepticism and the degree of openness to new or dissenting views. Popular movements showed signs of new life, and the academic analysis of global issues found more room for critical and dissenting views. In the future, as in the past, the balance of political forces will determine the outcomes of these struggles.

Bibliography:

- Boyd R E, Cohen R, Gutkind P C W (eds.) 1987 International Labour and the Third World: The Making of a New Working Class. Avebury, Aldershot, UK

- Bulletin of Comparative Labour Relations 2000 Multinational enterprises and the social challenge of the XXIst century. The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles at Work, Public and Private Codes of Conduct. Kluwer Law Journal 37, The Hague

- Compa L, Friedman S F 1996 Human Rights, Labor Rights and International Trade. University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia

- Galenson W 1981 The International Labour Organization: An American View. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI

- Ghebali V-Y 1989 The International Labour Organisation: A Case Study on the Evolution of U.N. Specialized Agencies. Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

- Gompers S 1957 Seventy Years of Life and Labor: An Autobiography, Taft P, Sessions J A (eds.). E. P. Dutton, New York

- Gross J A 1999 A human rights perspective on United States labor relations law: A violation of the right of freedom of association. Employee Rights and Employment Policy Journal 65

- ILO 1944 Declaration concerning the aims and purpose of the International Labour Organization, Geneva

- Langille B 1999 The ILO and the new economy. International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 5(3) (Autumn): 254

- Larsen S 1975 Labor and Foreign Policy: Gompers, the AFL, and the First World War, 1914–1918. Associated University Presses, Canterbury, NJ

- Lubin C R, Winslow A 1990 Social Justice for Women: The International Labor Organization and Women. Duke University Press, Durham, NC

- MacShane D 1992 International Labour and the Origins of the Cold War. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Martin G 1976 Madam Secretary: Frances Perkins. Houghton– Mifflin, Boston, pp. 427–30

- Morse D 1969 The Origin and Evolution of the ILO and its Role in the World Community. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

- Ostrower G B 1975 The American decision to join the International Labour Organization. Labour History 16(4) (Fall): 495–504

- Radosh R 1969 American Labor and United States Foreign Policy. Vintage Books, New York

- Reuther V 1976 The Brothers Reuther. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston, MA, pp. 329–59, 411–27

- Taft P 1957 The AF of L in the Time of Gompers. Harper & Brothers, New York

- Taft P 1959 The AF of L from the Death of Gompers to the Merger. Harper & Brothers, New York

- Taylor R 1999 Trade Unions and Transnational Industrial Relations. International Labor Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program) 1999 Human Development Report. Oxford University Press, New York

- Van Hooten F, Van Der Linden M (eds.) 1988 Internationalism in the Labour Movement 1830–1940, E. J. Brill, Leiden

- Windmuller J P 1995 International Trade Secretariats: The Industrial Trade Union Internationals. US Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labour Affairs, Washington, DC