Sample Evidence-Based Psychiatry Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

No country can afford health services to meet all the possible needs of the population, so it is advisable to establish criteria for which services to provide. Two basic criteria are the size of the burden caused by a particular disease, injury or risk factor, and the cost-effectiveness of interventions to deal with it (Bobadilla et al. 1994).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Health services are rationed. Access in most countries is controlled by money, waiting lists, and by the clinician’s decision about what should be done. Health services are concerned to avoid the explicit rationing that would follow if they adopted the position outlined above and so they have become concerned with maximizing efficiency. They have done this by limiting the input of funds, and by using scarcity to encourage improvements to the process of care. They keep asking ‘can science inform practice?’ an issue beset by many questions and too few answers. Yet it does seem relatively simple. Research is concerned with discovering the right thing to do; clinical audit with ensuring that the right things are done. The link that can close the gap is said to be evidence-based medicine: ‘the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al. 1996).

The evidence-based medicine movement seems to have originated from Archibald Cochrane’s set of essays ‘Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services,’ (Cochrane 1998) first published in 1971 and reprinted by BMJ Books in 1998. He argued that no new treatments should be introduced unless they had been shown in randomized controlled trials to be more effective than existing treatments, or equally effective and cheaper; and that one should evaluate all existing therapies, slowly excluding those shown to be ineffective or too dangerous. Cochrane actually meant efficacy when he wrote effectiveness (he acknowledged hating the word efficacy) but it is now usual to distinguish the three terms: efficacy, does the treatment work; effectiveness, does it work in practice; and efficiency, is it a wise expenditure of funds? The popular press is preoccupied with efficacy (can the doctors cure disease X?), not with effectiveness (do they?) or with efficiency (can we afford the cost?). Evidence-based medicine is concerned with identifying the efficacy of treatments and encouraging their implementation. The goal is increased effectiveness and efficiency (Andrews 1999).

Efficacy: ‘Does the treatment work?’ means does it produce benefit reliably over and above that to be expected from just being in treatment? Randomized placebo-controlled trials are valuable because they control for the uplifting effect of being in treatment (the true placebo effect). They also control for changes in symptoms and disability attributable to spontaneous remission, including the remission that occurs because people with chronic and fluctuating disorders commonly delay consulting until their disorder is particularly severe and can be expected to improve whatever happens. In some disorders the extent of this overall ‘placebo response’ is very large. In depression, it is two to three times as large as the change related to the present specific therapies, be they drugs or psychotherapy (see the discussion in Enserink 1999, pp. 238–40). That is, people given a sugar tablet will improve, not because of the tablet, but because of these other processes. People taking the active antidepressant tablet will improve more, but only one third of the overall change will be due to the antidepressant. It is for this reason that changes in symptoms with a specific treatment are suspect, unless they are shown to exceed the changes expected from a nonspecific placebo treatment.

With a few significant exceptions, most randomized controlled trials in psychiatry, even multicentre trials, have relatively small numbers of subjects. It is therefore usual to defer judgment until a number of trials have been done in different centers. If they agree that a certain treatment is better than placebo, then it probably is, but as most use different measures of outcome it has been necessary to develop a method for estimating the average degree of improvement with this treatment. Meta-analysis employs standard data analysis techniques to compare the results of studies by converting, if necessary, the results onto a standard metric, called an effect size. Even so, the wide range of outcome measures in use makes comparison difficult, and it is not always adjusted by expressing change in effect size terms. For example, while trials in depression almost always use the Hamilton scale so that results can simply be averaged, a meta-analysis of panic disorder found over 300 different measures in 58 studies, which has to be evidence of social irresponsibility in science. While each investigator will need to use a disorder-specific measure of symptoms, there is some real advantage in all using a generic measure of disability such as the short forms from the RAND medical outcomes study.

Structured systematic reviews are now common. In memory of Cochrane, a center at Oxford has been established to encourage and disseminate systematic reviews of the medical literature. These reviews abide by strict methodological guidelines and identify the level of confidence that the reader can place on any finding. In mental health, the dominant US publication is a book by Nathan and Gorman (1998). Any clinician, asked by a client what other treatments there are, would be obliged ethically to mention the treatments listed in that book as supported by type 1 evidence before offering advice about the treatment to be preferred. The self-help version of that book should be in every mental health clinician’s waiting room (Nathan et al. 1999).

Effectiveness: Does the treatment work in practice when applied by the average clinician to the average client? There is a paucity of such data. Such data as there are show that effectiveness is reduced as one moves from experimental practice to routine clinical practice. Too often treatment as usual seems almost ineffective. Thus the problem is not so much defining the treatments that work as overcoming the degradation of benefit that occurs in practice. There are four issues that undermine the potential effectiveness of a treatment: deficits in coverage, deficits in compliance, deficits in clinical competence, and treatment integrity. Epidemiological studies in the USA, Canada, the UK, and Australia show consistently that only a fifth to a half of people who meet criteria for a mental disorder get help for their disorder (Andrews and Henderson 2000). Coverage is therefore low, variably limited by access to services and by the expectation that there is little point in attending. Poor coverage when access is limited is understandable, but why should there be poor coverage when a national health service provides access? The Australian national mental health survey asked why the burden of depression persisted when access to care was free. Half the people who identified depression as their main complaint (and were disabled as a result) did not consult because they ‘had no need for treatment.’ There are data on the mental health literacy of Australians that show that the majority of the population think that relaxation and tonics are good for depression, and that medication is not. It is clear why they do not consult their doctors.

Deficits in compliance and treatment integrity are difficult to estimate, simply because auditing of either will produce a temporary change in behavior. There is evidence that asking people if they have taken all their medication is a valid measure of compliance; at least those who say they haven’t can be counseled. One advantage of providing patient treatment manuals for psychological treatments is that the manuals contain explicit sheets on which the homework can be recorded and reviewed. Like homework at elementary school, if the clinician doesn’t ask, the client doesn’t do. The patient treatment manual also serves to ensure treatment integrity. After all, the manual is the curriculum for the treatment program and clinicians have little opportunity but to follow the framework, personalizing it for each patient, and following the sequence in every case. All psychological therapies should be manualized, because psychotherapy is about learning, and most learning programs have text books.

Coverage and compliance concern the system and the consumer. Clinical competence and treatment integrity concern the physician. How do you make sure the physician knows what to do, and then does what should be done. The evidence-based medicine movement has clear ideas about how clinicians should practice. Ideally, clinicians should constantly be asking ‘what is the evidence about treatment for this type of patient with this type of disorder?’ Searching the Internet they should source systematic reviews, such as those from the Cochrane Collaboration, before deciding which treatment is appropriate. There are three problems. The first is time; busy practitioners, especially those in private practice, have no opportunity to consult sources in this way. The neediness of patients simply consumes the day. The second is that systematic reviews are about people who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria for RCTs, and who are unlike the pregnant woman, for whom information is needed. The third issue is that the methodological formalism required for such reviews may remove the very data or comments that would be helpful. Systematic reviews are essential, but they may need to be supplemented with more clinically relevant material.

Review journals are flourishing. For example, the aim of the British Medical Association’s journal Evidence Based Mental Health was to print one-page summaries of research that had met rigorous standards. Clinicians, with no time to do their own literature searches, could rely on the summaries to guide practice. To a large part this happens, but methodological formalism may be limiting the scope and obscuring meaning. In January 2000, the journal’s website had a summary of an RCT in which three sessions of CBT and three sessions of psychodynamic therapy were equally effective in relieving subsyndromal depression. The take-home message for the busy practitioner was unclear. Psychotherapy that requires transference can be completed in three meetings? CBT that teaches how to change thoughts and behaviors can be achieved in three sessions? That it is important to treat mild symptoms that do not constitute a disorder? Which is strange in a country like the UK, in which 70 percent of people with major depression do not see a doctor and most who do are treated inadequately. The review journals are important, but the editors need to think about the burden of the disease and the implications for practice, as well as about the probity of research designs. Complex problems are unlikely to have simple one-page answers.

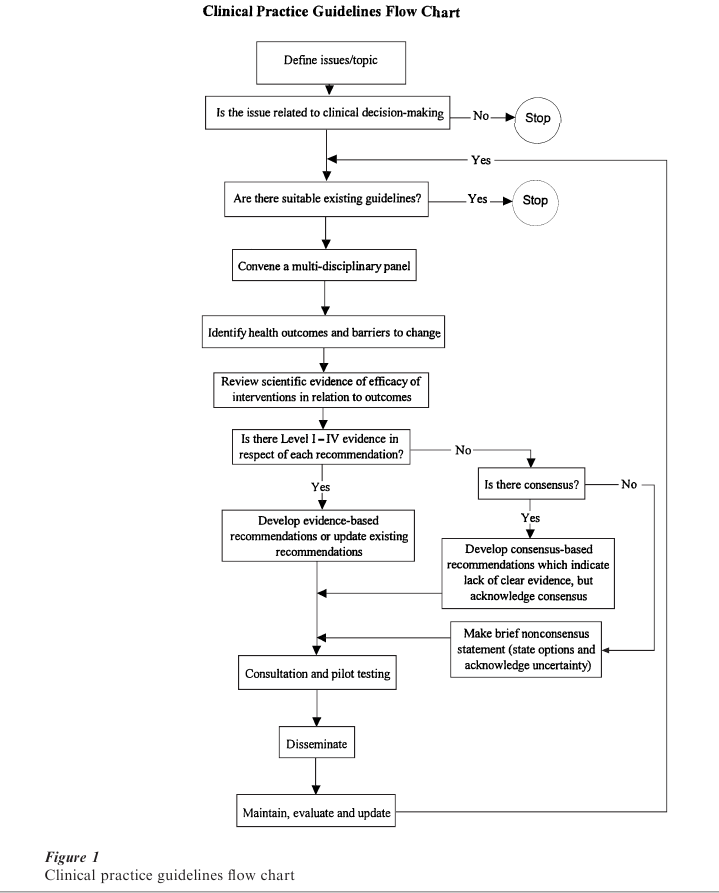

Clinical practice guidelines are the traditional avenue used to put research findings into practice. Properly written they can combine a continuum of information from good research to good clinical wisdom, differentiating between statements supported by research, and statements, no less valuable, supported by opinion. The steps in preparing clinical practice guidelines are illustrated in Fig. 1. In summary: when there is a clinical issue and there are no existing guidelines, a panel of all stakeholders should be convened to identify the desired health outcome. They should proceed by preparing a systematic review of efficacy of interventions in relation to this outcome, differentiating clearly between interventions supported by the differing levels of the weight of evidence (level 1a: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials; level 1b: at least one RCT; level 2: at least one controlled or quasi-experimental study; level 3: non-experimental descriptive studies; level 4: expert committee reports or opinions). Each statement in the guideline is qualified traditionally in accord with the quality of the supporting research evidence. Increasingly, the principal recommendations of guidelines require support from level 1a evidence, lower levels of evidence being valuable to fine-tune that principal recommendation for special groups of patients, or atypical clinical situations.

Most clinicians have access to at least half a dozen such guidelines, and many doctors in primary care have mountains of guidelines, so many that their ability to use any is questionable. While most originators claim that regular revisions will be issued, this has not proven to be the case. The problem is that guidelines have largely been written by advocates keen to support a position and, understandably, they are not keen to update the data in terms of new developments. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists produced guidelines for 1981–91 (Quality Assurance Project 1983), and in 2001 they at last began working on a revision of some of these. The American Psychiatric Association and the UK Royal College of Psychiatrists have also produced guidelines for their members. An attempt to produce mental health consensus guidelines that incorporated the views of all stakeholders—the various providers, the consumers and carers, and the public and private funders—appears to have run out of support: who wants to be fair when there is so much to be gained by being partisan? Moreover, when guidelines are produced by independent bodies such as the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research they can run foul of vested interests so that the impact is nullified (cf. breast cancer screening, spinal fusion) (Deyo et al. 1997). Clinical practice guidelines should be a flowering of the scientific method—find out what works and implement it—but too often they are political acts that represent the interests of an advocacy group.

Leaving aside the problem of the accuracy of the information, how is it possible to introduce guidelines that busy practitioners will follow. The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council recently convened a meeting to learn how 14 studies in medicine, surgery, and psychiatry fared as they sought to implement their guidelines. None fared well. Simply publishing the guidelines had no effect at all. The key elements seemed to be to produce guidelines that were simple, short, accurate, and current. Short meant on two sides of a plastic card, even if backed by a source book that contained the science. The content should be sponsored by a respected professional organization and the guidelines should represent a collaboration between all the stakeholders likely to use them, or be affected by them. They gain credence by being published in a reputable journal.

The rules for successful implementation of clinical practice guidelines are not at all clear, but look like a combination of hard work and marketing, done at a local hospital or regional professional organization level. Getting Research Findings into Practice (Haines and Donald 1998) is an excellent source book. The process is as follows: involve the key stakeholders and the clinical and management opinion leaders, have an accurate idea of what one wants to change, and a clear idea of the changes to organizational procedures, medical equipment, and clinical skills that will be necessary if implementation is to occur. Provide academic detailing to the clinicians so that all will have a chance to discuss and question the guidelines before implementation starts. Involve the consumers in the preparation of the guidelines and then in their implementation. Put the guidelines on the hospital or group’s homepage, and 10 percent of consumers will consult these before attending. Use clinical audit to show that change is occurring and to show improved clinical outcomes. If the change does not improve clinical outcomes, ask whether further implementation is wise. Sustain the whole process by showing an improved cost effectiveness profile and arrange that some of the savings benefit the clinicians who brought this about. Expect that the implementation procedure will cost a considerable amount in staff time; the time costs for staff to attend meetings to produce a simple change to the way acute asthma was managed in one hospital exceeded $50,000. The costs of implementation were perceived as inordinate even though that money was quickly recouped from the savings that accrued from the improved outcomes once the guidelines were implemented. If originators of the guide- lines are not prepared to do all this work then they should simply enjoy the process of producing them, for the guidelines will not influence practice. This is not to deny that identifying empirically supported treatments carried out by a profession does not have important professional and political advantages for the profession. Funders, providers, and consumers all like to pretend that efficacy is the same as effectiveness, and lists of empirically supported treatments feed this delusion.

Efficiency: Efficiency or cost effectiveness is about the wise expenditure of scarce health resources. Costing studies are now common; the problem is that most are based on efficacy calculations in which coverage, compliance, and treatment integrity are all believed to be perfect. As effectiveness is much, much less than efficacy, the true costs per unit of benefit are much, much more than those identified in the costing studies. Australia was the first country to require costing data to be submitted when pharmaceutical companies sought to have a new drug placed on the list of subsidized medications. It has rightly been praised for this. Enquiries as to whether the data submitted are cost effective data or cost efficacy data are met with the assurance that the former is the case. As the data are ‘commercial—in confidence’ they are not amenable to ‘freedom of information’ enquiries. None are published and one might suspect that most are estimates of cost effectiveness under ideal conditions in which effectiveness is presumed to equal efficacy. As psycho-logical therapies are not subsidized they are not subject to regulation, and randomized controlled trials about efficacy and cost are not required by any country. If we are to be anything more than a medicated society we do need such data.

League tables of the ‘cost effectiveness’ of medical interventions are beginning to appear. Few include mental health interventions. The median medical intervention cost in a study of 500 life-saving interventions was estimated as $19,000 per life year saved. In mental disorders, the principal burden comes from the years lived with a disability, not from the years of life lost. Nevertheless, shadow prices under $30,000 per disability-adjusted life year averted or quality-adjusted life year gained are said to be of interest to health planners. In specialized clinics, where costs and out- comes are known, it appears that drug and psycho-logical therapies for the common anxiety and depressive disorders can be provided at little more than $5,000 per life year gained. These figures are competitive and it might prove more advantageous if accurately costed league tables of empirically sup- ported therapies in mental disorders were to be prepared by an organization of high repute. I cannot think of a greater stimulus to the implementation of evidence-based psychiatry than some appreciation of the good bargains available. After all, treatment as usual that produces little benefit is very costly to both funder and consumer. The providers benefit in the short term, making the majority of their income from people who do not get better, but in the long term they become disillusioned by their lack of effectiveness. Evidence-based psychiatry can close the gap between research and practice, but it is not a trivial task. It can improve effectiveness to resemble efficacy and so result in better outcomes for patients, and that is not a trivial achievement. Isn’t that what mental health services are for?

Bibliography:

- Andrews G 1999 Efficacy, effectiveness and efficiency in mental health service delivery. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 33: 316–22

- Andrews G, Henderson S (eds.) 2000 Unmet Need in Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Bobadilla J L, Cowley P, Musgrove P, Saxenian H 1994 Design, content and financing of an essential package of health services. In: Murray C J L, Lopez A D (eds.) Global Comparative Assessments in the Health Sector. World Health Organization, Geneva, pp. 171–80

- Cochrane A L 1989 Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Ser ices. British Medical Journal, London

- Deyo R A, Psaty B M, Simon G, Wagner E H, Omenn G S 1997 The messenger under attack: Intimidation of researchers by special-interest groups. The New England Journal of Medicine. 336: 1176–80

- Enserink M 1999 Can the placebo be the cure? Science 284: 238–40

- Haines A, Donald A 1998 Getting Research Findings into Practice. BMJ Books, London

- Nathan P E, Gorman J M 1998 A Guide to Treatments that Work. Oxford University Press, New York

- Nathan P E, Gorman J M, Salkind N J 1999 Treating Mental Disorders: A Guide to What Works. Oxford University Press, New York

- Quality Assurance Project 1983 A treatment outline for depressive disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 17: 129–46

- Sackett D L, Rosenberg W M C, Gray J A M, Haynes R B, Richardson W S 1996 Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal 312: 71–2