Sample Emil Kraepelin Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Biographical Note

Emil Kraepelin was born on February 15, 1856 in Neustrelitz (Mecklenburg, West Pomerania, Germany). He studied medicine in Leipzig and Wurzburg from 1874 until 1878. During his medical studies in Wurzburg, Kraepelin worked as a guest student at the psychiatric hospital under the directorship of Franz Rinecker (1811–83). He began his professional life in 1878 working with Bernhard von Gudden (1824–86) at the District Mental Hospital in Munich, where he stayed until 1882. Kraepelin then moved to Leipzig, where he worked with Paul Flechsig (1847–1929) and Wilhelm Erb (1840–1921). He was promoted to university lecturer there in 1883.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

His lifelong personal and scientific relationship with Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) began in Leipzig. Encouraged by Wundt, Kraepelin wrote his Compendium of Psychiatry in 1883, the precursor of his influential textbook Psychiatry, which was to be published in nine editions between 1883 and 1927. Kraepelin stayed in contact with Wundt by correspondence and paid him several visits before Wundt’s death in 1920; in many of his publications he emphasized and acknowledged the importance of this relationship.

In 1884 Kraepelin married Ina Schwabe. After a short period of employment in Leubus (in Silesia) and Dresden, Kraepelin was appointed professor of psychiatry at the University of Dorpat in 1886. In 1891 he took over the chair of psychiatry at the University of Heidelberg. From 1903 until 1922 Kraepelin was ordinary professor of psychiatry in Munich where, in 1904, he opened the new building of the psychiatric hospital of the Ludwig Maximilian University, the main part of which is still in use. Despite the difficult conditions caused by World War I, Kraepelin founded the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt fur Psychiatrie (the German Research Institute for Psychiatry) in Munich in 1917 to encourage and improve psychiatric research (Weber 1991). During his time in Munich, Kraepelin’s colleagues at the university hospital and the Forschungsanstalt included Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), Franz Nissl (1860–1919), Korbinian Brodmann (1868–1918), Walter Spielmeyer (1879–1935), August Paul von Wassermann (1866–1925) and Felix Plaut (1877–1940)—to mention but a few. In 1924 the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt was integrated into the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and became in 1945 the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry as part of the Max Planck Society. Emil Kraepelin died in Munich on October 7, 1926.

2. The Concept Of Psychiatric Research

Wilhelm Griesinger (1817–68) had marked the turning point in nineteenth-century psychiatry by calling for thorough clinical and pathophysiological research based on the premise that ‘mental illness is a somatic illness of the brain.’ But Griesinger’s theory was by no means as simple as this one statement, which is so often quoted. He held clearly differentiated views on the problem of somato and psychogenesis, although favouring the first in the case of what was later to be called ‘endogenous psychoses.’

Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum (1828–99) continued the traditions of French psychopathology as represented by J. Falret and A.L.J. Bayle and developed a clinically orientated research method in the second half of the nineteenth century in Germany, taking the course of illness into special consideration. This, like Griesinger’s theory, was believed to be a victory over the speculative concepts of the so-called ‘romantic medicine’ and even more so an argument for a critical distance to the position of the harsh and unreflected ‘somaticists,’ who were no less dogmatic than some of the ‘psychicists.’ Kahlbaum had clearly recognized the methodological differences between pathological-anatomical and clinical-psychopathological work. With ‘progressive paralysis of the insane’ as an example he explained the route from the ‘syndrome-course unit’ (Syndrom-Verlaufs-Einheit) to the—postulated—etiologically-based ‘disease unit’ (Krankheitseinheit).

The influence on Kraepelin of the founder of experimental psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, can hardly be overestimated. Wundt’s aim was to establish psychology as a kind of natural science which relied on experimental data. He criticized the highly speculative approach of ‘philosophy of nature’ in the sense of Schelling and Schleiermacher, but did not agree with materialism or association psychology in the sense of Herbart either. At least in his earlier writings, Wundt favored a parallelistic point of view in the mind–body problem. Experimental research—and Wundt’s ideas were obviously the most fascinating for the young Kraepelin— may successfully be used in natural sciences as well as in psychology, without ignoring the epistemological differences between the mental and the physical. Kraepelin modified Wundt’s ideas by extracting what he regarded as useful for empirical research in psychiatry. That is why Wundt’s psychology, viewed through the ‘filter’ of Kraepelin’s texts, seems much more unified and straightforward than it really was. Kraepelin simplified and, so to speak, ‘smoothed out’ Wundt’s concept, but he did not falsify it.

Emil Kraepelin was not very interested in the philosophical basis and implications of psychiatric theory and practice. His view of what (natural) science was, and what impact it had or should have on social and political developments, was, as Engstrom (1991, 1995) has shown convincingly, typical for the way natural scientists saw themselves in Germany at the turn of the last century. Despite his skeptical attitude toward theoretical considerations in psychiatry, the following major theoretical frameworks can be identified as underlying—seldom explicitly, most often very implicitly—Kraepelin’s concept of psychiatry: realism, parallelism, experimental approach, naturalism.

2.1 Realism

In sharp contrast to the philosophical tradition of what is usually called ‘German idealism,’ Kraepelin, like most of his contemporaries in the field of natural sciences, believed in an independently existing ‘real world’ that includes other people and their healthy or disturbed mental processes. Kraepelin repeatedly pointed out that the psychiatric researcher has to describe objectively what really exists and what ‘nature presents to him’—the formulations differ, but the essence is a strictly realistic philosophy. The consequences for psychiatric nosology are evident: such realism will lead to the concept of ‘natural disease entities’ which exist completely independently of the researcher. The scientist describes what he finds, or—in stronger terms—describes ‘given things.’ His own activity in constructing scientific hypotheses or diagnostic entities is underestimated.

2.2 Parallelism

Kraepelin advocated psychophysical parallelism. Like Wilhelm Griesinger, whom he admired for his highly critical attitude toward speculative psychiatric theories, he disapproved of reductionistic materialism which identifies mental events with neurophysiological processes. Kraepelin spoke about two kinds of phenomena, somatic and psychological, which are decidedly different, but closely connected. Kraepelin defended the existence of mental phenomena against all kinds of what he, like Karl Jaspers, called ‘brain mythologies.’ Contrary to Wundt, however, Kraepelin, although calling himself a parallelist, did not enter the philosophical controversy about this concept. In particular, he did not critically differentiate between parallelism and interactionism and did not realize that any strictly defined parallelism makes it more than doubtful that mental life can still be regarded as an independent sphere and not just as having a one-to-one relationship with the somatic level; and this, of course, means (causal) determinism.

As a consequence of his somewhat ambivalent position in the mind–body debate, there is indeed an implicit tendency toward monism in Kraepelin’s writings, particularly when considering his ideas about psychology as a natural science. It should, therefore, be emphasized that this ‘monistic tendency’ was definitely not a metaphysical one, but a weak version of what may be called ‘methodological monism,’ insofar as he decidedly favored the quantitative methods brought forward by the natural sciences (Verwey 1985).

2.3 Experimental Approach

Kraepelin argued that the psychological experiment should become a major scientific tool, not only for the understanding of disturbed mental processes, but also for the understanding of healthy mental life. Both Wundt and Kraepelin realized the difference between a physical and a psychological experiment, but the experimental design did not differ significantly in the two areas. Kraepelin seems to have considered the experimental approach a kind of guarantee for the scientific status of psychiatric research. From this it may be inferred that he rated the experimental approach higher than the mere description of clinical phenomena, although the latter method was considered to be indispensable, especially if combined with follow-up examinations. Kraepelin developed and maintained a skeptical attitude toward subjective—especially biographically-determined—aspects of mental disorders, which could not be studied experimentally.

2.4 Naturalism

In his early writings—mainly in those on forensic topics—Kraepelin clearly expressed his opinion that a priori ideas, freedom of the will, and unchangeable moral values do not exist. Everything is more or less dependent on the time and the specific social and cultural context in which it is used. For Kraepelin, man is nothing but a part of nature, and anything man can do is a product of this natural existence: thus Kraepelin should be seen as an exponent of the evolutionism theory (Hoff 1998). Later in his life, he became somewhat more cautious concerning these matters, but there is no reason to believe that he substantially changed his mind. This naturalistic, ‘anti-metaphysical’ point of view of course made Kraepelin feel sympathetic with Darwinistic and biologistic theories, although he always rejected oversimplifications such as those in the monistic theories of Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), Jakob Moleschott (1822– 93), and Ludwig Buchner (1824–99).

3. Nosology

3.1 Basic Aspects

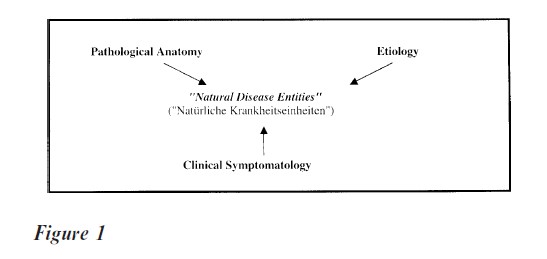

On the clinical level, Kraepelin changed the details of his diagnostic system over and over again. On the basic level, however, his nosology showed remarkable stability over time: between the second and the ninth editions of his textbook (i.e. from 1887 to 1927) Kraepelin did not change the central postulate. He stated that the essential features of all psychotic disorders will eventually be classified in a ‘natural’ system, no matter which scientific method is applied: anatomy, etiology and symptomatology, if developed sufficiently, will necessarily converge in the same ‘natural disease entities’ (see Fig. 1).

This very strong hypothesis is limited to a certain extent in three important theoretical papers, written between 1918 and 1920: ‘Ends and means of psychiatric research’ (‘Ziele und Wege der psychiatrischen Forschung’; 1918)), ‘Research in the Manifestations of mental illness’ (‘Die Erforschung psychischer Krank-heitsformen’; 1919) and ‘Clinical Manifestations of Mental Illness’ (‘Die Erscheinungsformen des Irreseins’; 1920). In these papers Kraepelin took into account contemporary arguments such as K. Birnbaum’s differentiation between pathogenetic and pathoplastic factors in Mental Illness or R. Gaupp’s hypothesis of the possibility of psychogenic delusion; he now acknowledged the value of defining certain syndromes as a middle course between nosologically unspecific symptoms and specific diseases. But—and this is the essential point—at no time did he abandon his postulate of underlying distinct and natural disease entities (Hoff 1994, 1995).

3.2 Clinical Aspects

Kraepelin’s clinical nosology is best separated into three periods.

3.2.1 The Early Period, 1880–91. This period can be characterized as the search for a reliable and valid psychiatric system between clear-cut naturalistic beliefs and the methodological framework of experimental psychology in the sense of Wundt. As regards nosology, Kraepelin slowly moved away from earlier nineteenth-century concepts which he criticized as being unreliable and ill-defined from a clinical and, especially, prognostic point of view. In these years the term ‘dementia praecox’ was not yet used. A group of clinically heterogeneous paranoid and hallucinatory psychoses tending to become chronic was labelled ‘Wahnsinn’ (insanity) and resembled the evolutions now known as schizophrenic psychoses leading to a residual state. In addition, Kraepelin introduced ‘Verrucktheit’ (madness) as a chronic psychosis with a better prognosis, that explicitly did not lead to residual states. The affective psychoses were split into the three groups: melancholia, mania, and periodical or ‘circular’ psychosis.

3.2.2 The Middle Period, 1891–1915. During these years Kraepelin’s thinking reached its most systematic and influential level as far as its clinical and scientific implications are concerned: Kraepelin significantly broadened his clinical experience and self-consciously created a complete nosological system. He finalized his concept of natural disease entities as discussed above. The main clinical result of this period—first clearly proposed in the sixth edition of 1899—was the well-known dichotomy of endogenous psychoses: that is, the separation of dementia praecox (schizophrenia) with—as he saw it—a poor prognosis, from manic-depressive illness (bipolar disorder) with a good, or at least better, prognosis. With respect to dementia praecox, he supposed an organic defect as the basis of the illness, a kind of ‘autointoxication,’ leading to the destruction of cortical neurons. The patient’s personality may promote the development of the psychotic illness, but it is not a central factor; contrary to most other nosological areas, ‘degeneration’ was believed to be of much less etiological importance in dementia praecox. ‘Paraphrenia’ was conceptualized as a psychosis with acute and heterogeneous clinical symptomatology, including the development of lasting deficits, but its separation from typical cases of dementia praecox was justified by the absence of massive disturbances of volition and by a much lesser degree of affective flattening.

In manic-depressive illness the etiology was said to be much less clear than that of dementia praecox. Kraepelin proposed a genetically-determined irritability of ‘normal’ affects, so that the psychosis itself emerged from certain predisposing ‘basic states’ (Grundzustande). The concept of degeneration was an integrative and central part of this hypothesis. In this period, Kraepelin integrated different types of circular or recurrent affective illness into the overarching concept of manic-depressive insanity (Manisch-depressi es Irresein) (6th edition 1899).

Kraepelin’s concept of paranoia was modified several times in this period. After the very broad concept of Verrucktheit of the early editions of Psychiatry, which was of restricted clinical use, he significantly narrowed it, especially in the 5th edition of 1896. Here, paranoia was defined as a severe and chronic delusional illness without constant alteration of personality and volition; the existence of abortive or benign cases was denied up to the 7th edition (1903 04). In the 8th edition (1915) this very rigid concept was broadened again, but not as much as in the early versions. Kraepelin now accepted cases with low severity and a comparably good prognosis, but he maintained the strict separation of dementia praecox and paranoia.

In Kraepelin’s view—highly typical of the way of thinking within the theoretical framework of degeneration theory—disorders of personality resulted from a circumscript retardation of psychological development. He argued that not all patients with personality disorders reach a ‘normal’ or mature level of affective and cognitive functioning. Therefore, in this field, it made no sense to delineate clear-cut disease processes as in dementia praecox and manicdepressive psychosis.

3.2.3 The Later Period, 1916–26. During this final period, Kraepelin reacted to several commentaries and criticisms of his nosology, for example, A. E. Hoche’s syndromatic theory and E. Kretschmer’s suggestion to supplement the Kraepelinian system with a multidimensional approach. He moved towards an internal broadening of his system by reformulating his disease concept as discussed above; he combined a more differentiated view of pathogenesis and the role of individual psychological factors with a strong and unchanged position on the existence of ‘natural disease entities.’ Compared to this differentiation of the theoretical basis during these years, changes in clinical nosology were small.

4. Kraepelin And Present-Day Psychiatry

Kraepelin’s psychiatry became so influential during his lifetime, because it offered a pragmatical, clinical and prognosis-oriented nosology, developed by a self-confident author who focused on straightforward quantitative and naturalistic research methods. He claimed to abandon speculative aspects of psychiatry as far as was possible, although he himself did— unintentionally—‘import’ a number of implicit theoretical and, in part, highly speculative aspects into psychiatry.

In the decades after World War II, Kraepelinian ideas—and ‘biological’ concepts in general—lost much of their influence and were discussed mainly from the historical point of view. However, Kraepelin’s concepts were ‘rediscovered’ in the 1960s and 1970s when ‘biological psychiatry’ became the most influential (and most self-confident) field of psychiatric research. In particular, researchers and clinicians from the English-speaking countries viewed themselves as ‘Neo-Kraepelinians’ (Blashfield 1984). But ‘NeoKraepelinianism’ is not a scientific theory in the strict sense. At present, it is an important and heterogeneous set of concepts, trying to create a basis for biological research in clinical psychiatry. Of course it does not just repeat Kraepelinian ideas. Central to this set of concepts is the intention to identify the biological basis—the ‘natural’ basis, in Kraepelin’s words—of mental disorders. But these findings may well lead to a nosological system quite different from Kraepelin’s, a topic which has attracted much interest at the end of the twentieth century. Many authors have postulated a ‘denosologization’ of psychiatric research, especially in biological studies (e.g., van Praag et al. 1987). The idea is to prevent nosological prejudices from hampering research by restricting the interpretation of data to the limits of ‘classical’ concepts, especially the Kraepelinian dichotomy of endogenous psychoses. There might (and will) be, these authors argue, biological findings that reveal an entirely different distribution in psychiatric patients than that expected within the framework of classical nosology. Such an approach, though modifying Kraepelinian nosology, does not stand in real contrast to his basic ideas. On the contrary, Kraepelin himself often stressed that all diagnostic criteria and categories were due to change according to the actual state of the art in psychiatric research—leaving the postulate of the existence of natural disease entities untouched.

‘Neo-Kraepelinian’ authors are—as was Kraepelin himself—at risk of overestimating the explanatory power of biological findings; for example, by accepting only biological criteria for nosology, and dismissing psychopathology as ‘unscientific.’ Nosological prejudices or dogmas do, of course, exist in psychopathological approaches as well as in biological ones, and they always severely obstruct research.

In the context of ‘Neo-Kraepelinianism,’ the modern operationalized diagnostic systems ICD-10 and DSM-IV should be considered. Their main impetus is to improve the reliability of psychiatric diagnoses by establishing clear diagnostic criteria. They focus on the behavioural level by means of clinical description and try to avoid interpretation of symptoms. Whereas Kraepelin’s nosological system—at least implicitly— included a number of etiological hypotheses and epistemological presuppositions, operationalized diagnostic systems aim to avoid etiological considerations (a concept which is often, incorrectly, called an ‘atheoretical approach’). But in spite of these theoretical differences, both Kraepelinian nosology and modern diagnostic systems run the risk of uncritically reifying their constructs called ‘diagnostic entities.’ This is why the authors of DSM-IV, for example, warn their users not to regard diagnostic categories as definite or ‘natural’ entities, but as conventions which need further verification. Especially in forensic psychiatry, diagnostic systems are sometimes misinterpreted as collections of natural constants, quasiautomatically leading to diminished responsibility (e.g., pathological gambling or kleptomania).

In summary, Kraepelin’s psychiatry was not only highly influential in his lifetime, but gained wide acceptance toward the end of the twentieth century, as the focus of psychiatric research again shifted to biological topics. It is of crucial importance that present-day psychiatry—be it ‘neo-Kraepelinian’ or not—adopts a comprehensive view of Kraepelin’s scientific work, embedded in a thorough knowledge of its complex conceptual history (Berrios and Hauser 1988). Otherwise, as well as benefiting from Kraepelin’s ideas, psychiatry will also be restricted by their conceptual limitations.

Bibliography:

- Berrios G E, Hauser R 1988 The early development of Kraepelin’s ideas on classification: a conceptual history. Psychological Medicine 18: 813–21

- Blashfield R K 1984 The Classification of Psychopathology— Neo-Kraepelinian and Quantitative Approaches. Plenum Press, New York

- Engstrom E J 1991 Emil Kraepelin: psychiatry and public affairs in Wilhelmine Germany. History of Psychiatry 2: 111–32

- Engstrom E J 1995 Kraepelin—Social Section. In: Berrios G E, Porter R (eds.) A History of Clinical Psychiatry. The Origin and History of Psychiatric Disorders. Athlone, London, pp. 292–301

- Hoff P 1994 Emil Kraepelin und die Psychiatrie als klinische Wissenschaft. Ein Beitrag zum Selbst erstandnis psychiatrischer Forschung. Springer, Berlin

- Hoff P 1995 Kraepelin—Clinical Section. In: Berrios G E, Porter R (eds.) A History of Clinical Psychiatry. The Origin and History of Psychiatric Disorders. Athlone, London, pp. 261–79

- Hoff P 1998 Emil Kraepelin and forensic psychiatry. Inter- national Journal of Law and Psychiatry 21: 343–53

- Kraepelin E 1883–1927 Psychiatrie. Nine editions: 1883, Abel, Leipzig; 1887, Abel, Leipzig; 1889, Abel, Leipzig; 1893, Abel, Leipzig; 1896, Barth, Leipzig; 1899 (2 vols.), Barth, Leipzig; 1903 04 (2 vols.), Barth, Leipzig; 1909–15 (4 vols.), Barth, Leipzig; 1927 (2 vols.), Barth, Leipzig

- Kraepelin E 1918 Ziele und Wege der psychiatrischen Forschung. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 42: 169–205

- Kraepelin E 1919 Die Erforschung psychischer Krankheitsformen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 51: 224–46

- Kraepelin E 1920 Die Erscheinungsformen des Irreseins. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 62: 1–29

- Kraepelin E 1983 Lebenserinnerungen. Hippius H, Peters G, Ploog D (eds.), with the collaboration of P Hoff and A Kreuter. Springer, Heidelberg Berlin New York. English translation (1987): Memoirs. Springer, Berlin

- Van Praag H M, Kahn R S, Asnis G M, Wetzler S, Brown S L, Bleich A, Korn M L 1987 Denosologization of biological psychiatry or the specificity of 5-HT disturbances in psychiatric disorders. Journal of Affecti e Disorders 4: 173–93

- Verwey G 1985 Psychiatry in an Anthropological and Biomedical Context—Philosophical Presuppositions and Implications of German Psychiatry 1820–1870. Reidel, Dordrecht

- Weber M M 1991 Ein Forschungsinstitut fur Psychiatrie. Die Entwicklung der Deutschen Forschungsanstalt fur Psychiatrie Munchen 1917–1945. Sudhoffs Archi 75: 74–89