Sample Public Psychiatry And Public Mental Health Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

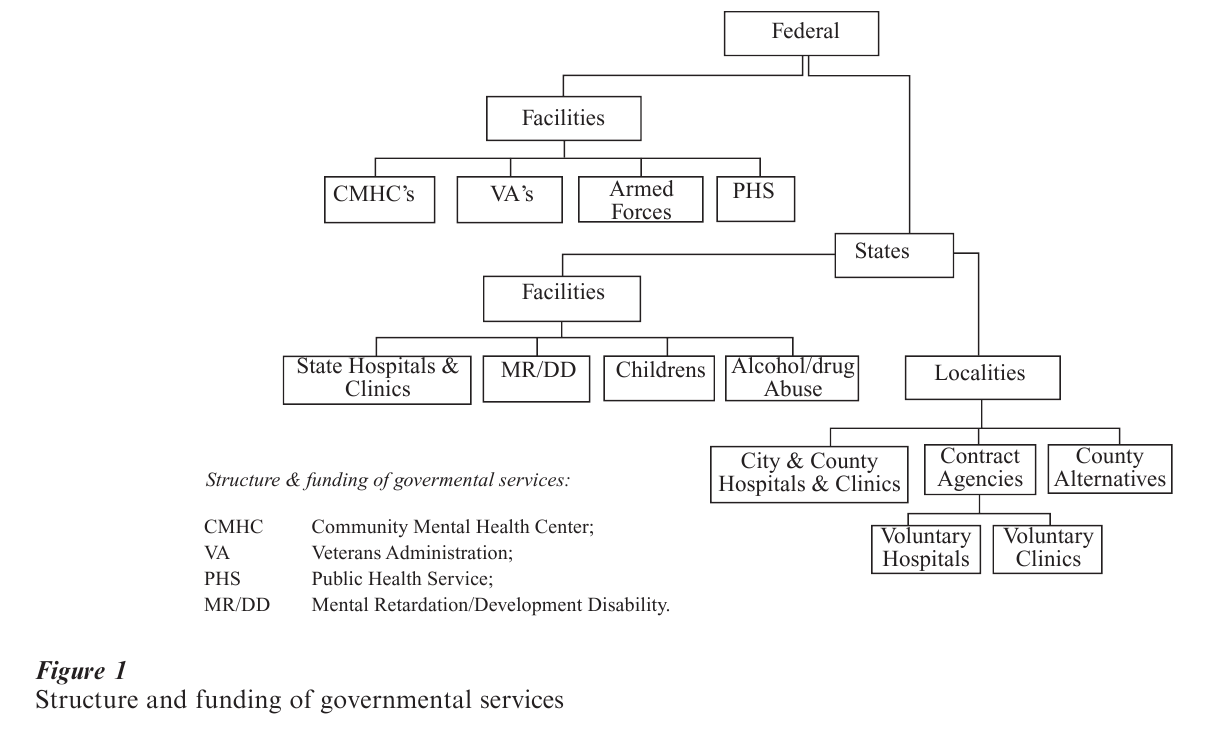

Public psychiatry in the US encompasses several different elements: buildings, such as state mental hospitals; programs, such as community mental health centers; and insurance mechanisms, such as Medicaid and Medicare, that enable poor or elderly recipients (respectively) to receive care in private facilities. Public mental health systems are found at all levels of government: the federal government runs one of the largest health care systems in the world, the Veterans’ Administration Medical System, all individual states run state psychiatric hospitals and systems, and local governments (e.g., cities and counties) run hospitals and clinics. In this research paper, both public psychiatry and public mental health systems will be discussed simultaneously, starting with their historical context and moving on to a more detailed examination of their elements.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The History Of Public Psychiatry And Public Psychiatric Systems

For many years after the US was colonized, there were no services for the mentally ill. In time, local communities built jails, workhouses, and almshouses or poorhouses, intended for ‘rogues and vagabonds,’ the ‘idle and disorderly,’ and the needy, respectively, to which mentally ill persons were sent if violent, disruptive, or simply wandering. While the first facility for the mentally ill, the ‘Publick Hospital’ in Williamsburg, Virginia, opened in 1752, it was not until the 1840s that Dorothea Dix, a pioneering advocate for the mentally ill, sought higher governmental responsibility for this population, and as a consequence, state mental hospitals and systems flourished (Talbott 1978). The federal government entered the scene in the eighteenth century with the creation first of Public Health Service Hospitals for the Merchant Marine, then Veterans Hospitals and finally, in 1963, Community Mental Health Centers. In some ways, the federal government’s commitment to returning the treatment and care of the mentally ill back to their communities represented a coming full-circle from the jails, workhouses, and almshouses or poorhouses of colonial days, but now this responsibility was coupled with the technology, programs, and staffing necessary to provide effective care nearer to home, family, and work. Thus, by the turn of the twentieth century there was a rich variety but often confusing multiplicity of mental health services sponsored by different governmental levels and agencies extant in this country (Fig. 1).

2. City And County Care

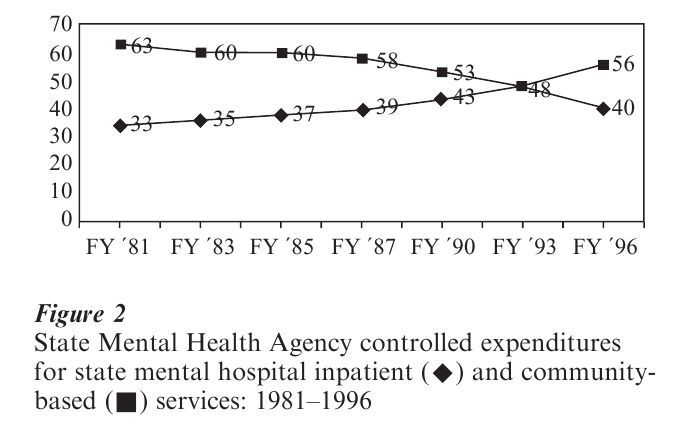

As mentioned above, the very first public institutions in which the mentally ill were cared, were county or city jails, workhouses, and almshouses or poorhouses. While these ‘houses’ existed for a number of decades (Rothman 1971), in the 1880s the mentally ill began to be cared for and treated in separate psychiatric hospitals, established by individual states. However, to this day, some cities (e.g., New York, New Orleans, San Francisco) and some counties (e.g., Cook (Chicago), Milwaukee, San Diego) have city and county general and/or psychiatric facilities. In addition, as also was mentioned above, the federal legislation in the 1960s creating community mental health centers plus the devolution of the state’s single authority to counties in the 1980s (Hogan 1999) have ensured a prominent role for local entities in taking public responsibility for the mentally ill at the close of the twentieth century. In terms of numbers, at their height in 1955, city and county mental health facilities cared for only 100,000 persons, compared to the 460,000 persons residing in state hospitals. Today there are fewer than a dozen city or county facilities remaining, caring for 10,000 patients. Recently, the Robert Wood Johnson. Foundation initiated a project in nine cities to ‘devolve’ mental health services from state to city ‘quasi-public authorities’ (Goldman et al. 1990). Because of these and other initiatives to move from (state) institutional to (local) community care, the majority of moneys allocated by each state now goes to community-directed mental health care (Fig. 2).

3. State Mental Health Services

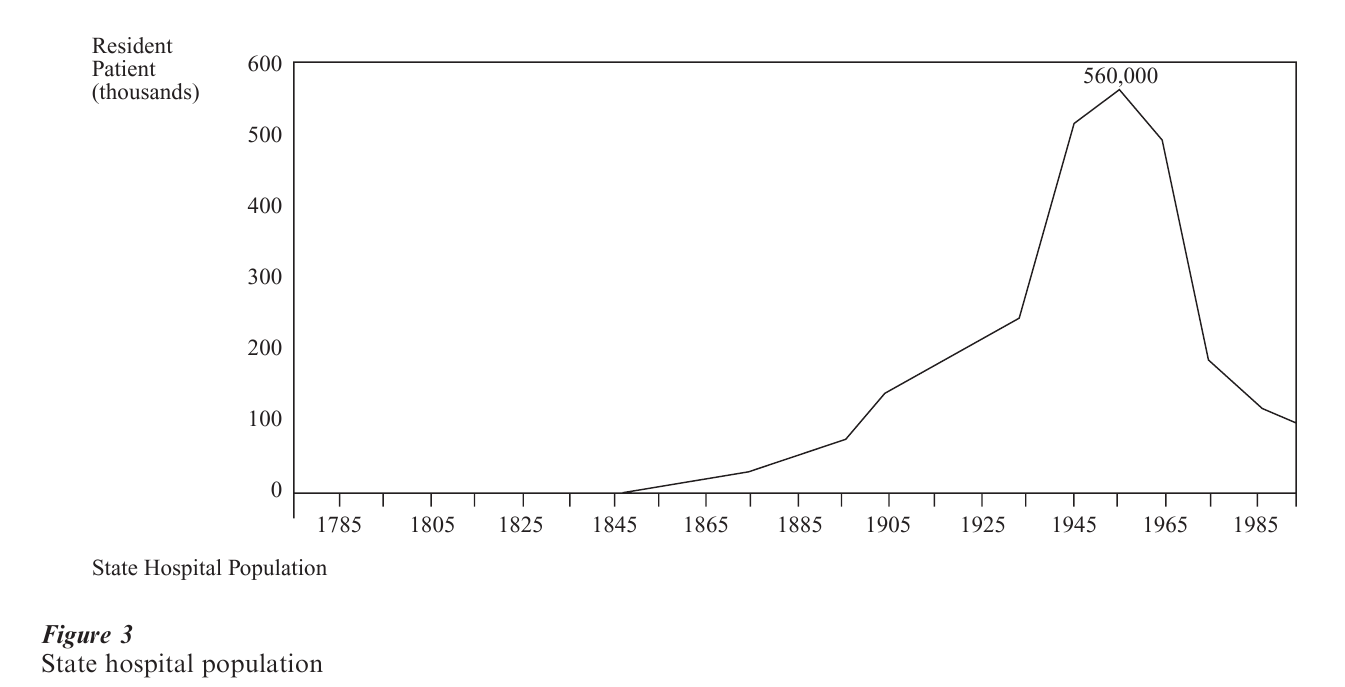

As mentioned above, the first facility for the mentally ill, the ‘Publick Hospital’ in Williamsburg, Virginia, opened in 1752. Called ‘public(k),’ the hospital was actually private and it was not until the 1820s and 1830s that state governmentally supported and run psychiatric hospitals came into being. While Massachusetts and New York pioneered in opening new facilities to accommodate for the need for treatment and care of the mentally ill, other states lagged behind until the 1840s when Dorothea Dix, a Sunday-school teacher, sought first federal and then state initiatives to care for all the mentally ill in America. From this point to 1955, state mental hospital systems grew; first slowly, and then with the waves of new immigrants, more quickly (Talbott 1978). By 1955, about 460,000 Americans were housed in such facilities (Fig. 3).

The role of the state mental hospital throughout its first century was comprehensive and inclusive; it provided almost everyone almost all the care and treatment then imaginable and available, including housing, food, clothing, supervision, social services, medical, psychiatric and dental services, and leisure time activities. If the number of admissions grew, new hospitals were built. Alternatives to state hospitals began to appear in the US starting in 1855 beginning with the Farm of Sainte Anne’s in Illinois, and eventually encompassed cottages on the grounds, ‘boarding out,’ ‘aftercare,’ or outpatient clinics, traveling clinics, crisis intervention, satellite clinics, day, night, and weekend hospitals, social and vocational rehabilitation, home care, and halfway houses. However, the creation of all these ‘alternatives’ did not reverse or halt the increasing population treated in state facilities—until 1955. In that year, deinstitutionalization of these large facilities began as the result of a combination of technological (a new, the first, antipsychotic medication) and philosophical (that care in the ‘community,’ nearer family, work, and friends, was better than that in ‘asylums’) initiatives, soon to be joined by legal (the rights to treatment, to refuse treatment, and to be treated in less restrictive settings) and economic (medical insurance via Medicaid and Medicare for treatment in the community and income support via Supplemental Security Income for housing in the community) forces. In the next 30 years, the population in state hospitals fell 80 percent. Thus, at present, there are fewer than 90,000 residents in state facilities. It must be noted, however, that state governments were not only responsible for state mental hospitals (Fig. 1), but for ‘aftercare’ and outpatient clinics, as well as facilities and clinics for children and persons suffering from alcohol and drug abuse and mental retardation/developmental disorders, and these services have continued to this day.

4. Federal Mental Health Services

4.1 Veterans’ Hospitals

While pensions, cash payments, and land grants were awarded to veterans of the Revolutionary War by grateful states and the federal government, it was not until the American Civil War (1861–1865) that national veterans’ homes were established (Godleski et al. 1999) and not until after World War I, in the 1920s, that health benefits were offered to all veterans. By 1930, 4.7 million veterans were being served by 54 hospitals and in 1995 the ‘Veterans Administration’ system of care included 172 medical centers, 375 outpatient clinics, 133 nursing homes, 39 ‘domiciliary’ care facilities, and 202 ‘Vet Centers’ (largely urban drop-in centers).

4.2 Military Psychiatric Services

Physicians have always accompanied American forces during war. The recognition of the role of stress in combat was first documented in America during the Civil War when ‘combat heart’ was often diagnosed. In World War I, psychiatrist Thomas Salmon visited the battle lines in France before America’s entry and it was his observation of the difference in the practices and outcomes of the French (treatment near the lines, expectation of recovery; with low resultant disability) and English (evacuation; with high disability) in treating ‘shell-shock’ victims that predicated the American military’s practice henceforth. In World War II and in Korea, these lessons had to be re-learned but by Vietnam, American psychiatrists were inducted into the Armed Forces in significant numbers and assigned to both (a) hospitals in combat and evacuation areas and (b) line troop divisions, where they practiced ‘preventive psychiatry’ (Talbott 1966). Currently, to serve a ‘peacetime military’ of almost 1 million men and women, there are approximately 300 psychiatrists on active duty.

4.3 Public Health Service Hospitals

In 1798, Congress established the US Marine Hospital Service—the predecessor of today’s US Public Health Service—to provide health care to sick and injured merchant seamen (History of the Office of the Surgeon General 1999). Eventually, 25 hospitals were established across the country (Mullen 1989). In 1981 these hospitals began being phased out and at present the Surgeon General’s Office and the Public Health Service, while active in articulating policy (on smoking, the treatment of schizophrenia, etc.) and employing 6,000 persons who serve as a ‘uniformed cadre of health professionals on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in the event of a public health emergency,’ does not run nonresearch related clinical services.

4.4 The National Institutes, Administrations, And Centers

The first element in the federal array of research laboratories and agencies to be established was the Laboratory of Hygiene in 1887; the first psychiatric component was the Division of Mental Hygiene of the US Public Health Service in the 1930s. The National Cancer Institute was the first of the now 25 national institutes now comprising the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to be established for research; the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) coming into being in 1946. The research mission was broadened in the 1950s and 1960s to include teaching and services (e.g., community mental health centers) as well as alcohol and substance abuse treatment and prevention. Soon there were Institutes on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and Alcohol Abuse (NIAA) and in 1968 the Health Services and Mental Health Administration was established as an umbrella organization to house all of them. In 1973, NIMH rejoined the NIH and later came under a new ‘umbrella,’ the Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA). Finally, in 1992, prevention, services, and services research were separated off into a new agency—the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), while the NIMH, NIDA, and NIAA remained in the NIH as ‘research institutes.’

4.5 The Community Mental Health Center

As mentioned above, since colonial days, localities had always provided some services. But, in 1963, the shift from localities to states to federal auspices came full circle, and it was the federal government that legislated the establishment of what was intended originally by President John F. Kennedy’s administration to be about 750 community mental health centers (CMHCs), each of which was to serve 75,000–150,000 persons through the provision of 10 essential services (inpatient, outpatient, partial hospital, emergency, consultation and education, diagnostic, rehabilitative, precare and aftercare, training and research, and evaluation) (Glasscote et al. 1969). While the 1963 legislation had to be amended in 1975 to include care for children and the elderly and those suffering from alcohol and drug abuse as well as transitional housing, follow-up care, and screening for courts and agencies prior to hospitalization, the model of the CMHC was a powerful one in the US for most of the last half of the twentieth century. At present, while the US cannot claim to have either comprehensive or universally available, federally initiated community mental health centers, there are 675 in the nation (Ray and Finley 1994).

4.6 Federal Entitlements For Community Care

The blind and needy aged have been provided federal ‘Social Security’ to enable them to make ends meet since 1935, and in 1950 persons suffering from other disabilities, including mental disorders, were included under two additional programs: Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Income (SSDI). In 1966, two other large ‘public’ populations, the poor and the aged and disabled were guaranteed medical insurance through two federal entitlement programs, Medicaid and Medicare, respectively. What no one had realized at the time was the fact that with these four massive federal entitlement programs, the mentally ill could ‘afford’ to live and receive treatment from ‘private’ clinics and general hospitals rather than ‘public’ state hospitals. This further added to the technological, philosophical, and legal forces moving psychiatric care and treatment in America from institutional to community care; albeit publicly financed. In 1997, 13.4 percent (37,514 million) of the population was covered by Medicare and 13 percent (35,028 million) by Medicaid; by 1994, 16.5 percent (42,878 million) of the population was covered by Social Security, 10 percent (26,281 million) by SSI, and 1.5 percent (5,893 million) by SSDI (US Bureau of the Census 1998).

4.7 Community Support And Case Management

Starting in 1977–1978, the NIMH provided grants to community agencies to initiate community support programs. Such a system was to include: identification of the population, assistance in applying for entitlements, crisis-stabilization, psychosocial rehabilitation, supportive services, medical and mental health care, back-up support to families, involvement of concerned community members, protection of client rights, and case-management (Shaftstein et al. 1978). Like the CMHC, this model was compelling and moved community services to adopt such strategies and services even in the absence of federal moneys. Most widely undertaken have been case management programs for high-intensity and average utilizers. It is impossible to estimate how many community support and case management systems there are in America today, but it is in the tens of thousands.

4.8 The Indian Health Service

Members of Federally recognized Indian tribes and their descendants have been eligible for services provided by the Indian Health Service (IHS) since 1787. The IHS, part of the US Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services, operates a comprehensive health service delivery system for approximately 1.5 million of the nation’s two million American Indians and Alaska Natives and in 1999 its annual appropriation was approximately $2.2 billion. There are more than 550 federally recognized tribes in the US whose members live mainly on reservations and in rural communities in 34 states, mostly in the western US and Alaska. IHS services are provided in three ways; by the IHS directly, through tribally contracted and operated health programs, and by purchasing care from more than 2,000 private providers. As of March 1996, the federal system consisted of 37 hospitals, 64 health centers, 50 health stations, and five school health centers. In addition, 34 urban Indian health projects provide a variety of health and referral services. The IHS clinical staff consists of approximately 840 physicians (approximately 80 of whom are psychiatrists), 100 physician assistants, and 2,580 nurses. As of March 1996, American Indian tribes and Alaska Native Corporations administered 12 hospitals, 116 health centers, three school health centers, 56 health stations, and 167 Alaska village clinics.

5. The Correctional System

The correctional system in America cuts across all governmental levels: federal, state, and local (city county). It may well house more mentally ill persons than any other ‘governmental health system.’ There are about 10 million adults booked into US jails each year and more than 1.5 million persons currently incarcerated. The US Bureau of Justice estimates a rate of mental illness in local and state jails of over 16 percent and in federal prisons of over 7 percent; thus over 250,000 mentally ill persons are in prison and jail on any one day (Ditton 1999). It is not known how many psychiatrists are employed in the correctional system nor how many services are rendered.

6. Public Managed Care

In the 1930s the Kaiser Corporation, a large industrial concern, formed the first employer-run group practices in America to reach its employees working in rural areas. These tightly run group practices became known as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and in the 1970s were promoted by the Nixon Administration. HMOs, along with other forms of tightly managed forms of service provision, have grown and expanded from their original base serving employed persons through industry or ‘private’ insurance to serving ‘public’ populations, e.g., the aged, disabled, and poor who are insured by Medicare and Medicaid. The popularity of such ‘managed care’ as a method of cost-control and provision is apparent from the fact that, in 1992, the percentage of Americans covered by managed-care programs exceeded those covered by ‘traditional’ (e.g., Blue Cross Blue Shield) insurance plans. In the 1990s, the federal and state governments have actively sought to enroll their publicly funded populations (e.g., those receiving Medicaid and Medicare) in such programs. Estimates of the percentage of Medicare recipients enrolled in managed care programs are at present over 10 percent nationally; regarding Medicaid, at present every state in the union has begun a ‘managed Medicaid program,’ has applied for federal government permission to do so, or is actively discussing it.

7. The Future

The future of public psychiatry and public mental health systems is unknown. While some systems (e.g., county and state systems) have endured for almost the entire three centuries of our young country’s existence, others (such as public managed care) are growing at a rate that will surely diminish the importance and even existence of these traditional systems. What is known, however, is that until poverty and severe mental illness no longer exist there will be public psychiatrists and public mental health systems.

Bibliography:

- Ditton P M 1999 Mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 174463

- Glasscote R M, Sussex J N, Cumming E, Smith L H 1969 Community Mental Health Center: An Interim Appraisal. Joint Information Service of the American Psychiatric Association and the National Association for Mental Health, Washington, DC

- Godleski L S, Vadnal R, Tasman A 2001 Psychiatric services in the veterans’ health administration. In: Talbott J A, Hales R E (eds.) The Textbook of Administrative Psychiatry: New Concepts for a Changing Behavioral Health System. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

- Goldman H H, Morrissey J P, Ridgely M S 1990 Form and functions of mental health authorities at RWJ Foundation program sites: Preliminary observations. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41: 1222–30

- History of the Office of the Surgeon General 1999 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/osg/sghist.htm

- Hogan M F 2001 State and county agencies. In: Talbott J A, Hales R E (eds.) The Textbook of Administrative Psychiatry: New Concepts for a Changing Behavioral Health System. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

- Indian Health Service Internet Home Page 1999 http://www.ihs.gov

- Mullen F 1989 Plague and Politics: The Story of the United States Public Health Service. Basic Books, New York

- Ray C G, Finley J K 1994 Did CMHCs fail or succeed? Analysis of the expectations and outcomes of the community mental health movement. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 21(4): 283–93

- Rothman D J 1971 The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic, 1st edn. Little, Brown, Boston

- Shaftstein S S, Turner J E, Clark H W 1978 Financing issues in providing services for the chronically mentally ill and disabled. In: Talbot J A (ed.) Ad Hoc Committee on the Chronic Mental Patient. The Chronic Mental Patient: Problems, Solutions, and Recommendations for a Public Policy. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

- Talbott J A 1966 Community psychiatry in the army. Journal of the American Medical Association 210(7): 1233–7

- Talbott J A 1978 The Death of the Asylum: A Critical Study of State Hospital Management, Services, and Care. Grune and Stratton, New York

- US Bureau of the Census 1998 Statistical Abstract of the United States, 18th edn. Washington, DC