View sample disease, health, and aging research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Developmental psychology’s goal is to describe, predict, and understand the changes that come with age. Developmental psychology is a multidisciplinary field within psychology—a field that cuts across all of the standard areas of psychology. We adopt the conventional terminology for changes, which implies variations in longitudinal measurements on the same persons over time; this is the core of the psychology of aging. We reserve the term age differences for cross-sectional age comparisons at a single point in time; such comparisons are the province of experimental aging research or a psychology of the aged. Understanding the variance accounted for by particular health problems or disease statuses requires both approaches. The key term in developmental psychology is age—that is, the age at time of measurement, the age at the beginning and at the end of the measurement period, the age at the onset of a disorder, and the age at death. Developmental psychology sees age as more than just a marker variable or placeholder. A basic contribution of developmental psychology has been the development of methodological advances to improve ways to assess age changes in the aforementioned contexts. Health and disease are prominent factors that influence changes associated with age; thus, this research paper examines the measurement and meanings of health and disease and their contribution to our understanding of the aging process.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In this research paper we seek to answer the question of what understanding health can add to developmental psychology. It is clear that developmental psychology sees health primarily as a topic of worry and concern to aging persons. It is a source of stress, requires coping, and can start a cascade of life events. It is an extremely important contextual variable whose content can exert considerable impact, depending on the particular area of study.

Disease is an entity physicians treat; it is the province of medicine and—for psychologists—behavioral medicine. Cognition is perhaps the most important aspect of development that is changed when health is compromised. What is important to note here is that the relationships are bidirectional. Not only do changes in health status precede changes in personality, cognition, and social functioning, for example, but changes in health status can also be the result of basic developmental changes in other areas of life. Developmental psychology’s perspective is closer in this regard to public health concerns about the global burden of disease—which seeks to measure the cost in human terms of these parts of the human condition (Murray & Lopez, 1996) rather than as mechanisms for understanding developmental change.

In 1990 a special issue of the Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences examined the relationship between health and aging (Siegler, 1990). Confronting the study of aging for the next century are new realities that have developed since that special issue was published over 10 years ago: (a) the explosion of input from other disciplines, (b) the emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease and what this has meant for research, (c) changes in the health status of aging populations reflected in demography and centenarian studies, and (d) the genetic revolution. A subtext of these findings is reflected in the samples that are being studied. In the past—when developmental psychology researchers required respondents to be healthy enough to get to the laboratory (see Siegler, Nowlin, & Blumenthal, 1980)—researchers found that selection biases were occurring as the group got older; they simply noted the fact, however, and continued to do research the way they always have. As data have become available from epidemiological studies that include measures of cognition, personality, or both (e.g., see Fried et al., 1998, from the Cardiovascular Health Study; M. F. Elias, Elias, D’Agostino, &Wolf, 2000, from the Framingham Study), we are seeing an explosion of relevant articles in the epidemiological literature that can contribute to our understanding of aging and health. The use of population samples in our research—such as in the Berlin Aging Study (Baltes & Mayer, 1999)—and the addition of measures of cognition to the Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) study (e.g., see Herzog & Wallace, 1997; Zelinski, Crimmins, Reynolds, & Seeman, 1998) have allowed us to better understand estimates of the effects of varying amounts of complete data and to better evaluate the costs and benefits of various sampling approaches.

Clearly, there are important bidirectional relationships between health and cognition, personality, social relationships, and—in particular— the very definition of successful aging. These psychosocial factors have an impact on health status and disease incidence and progression, and specific diseases have major impacts on cognitive, personality, and social functioning. These relationships were recognized by the National Academy of Science Committee’s report on the aging mind (Stern & Carstensen, 2000), and they can be seen in a commissioned chapter by Waldstein (2000) that reviews the findings of medical conditions on cognitive functioning. The regular inclusion of health reflects a major research development in adult development andaging;thisdevelopmenthastakenplaceinthepast5years and reflects recognition of the centrality of the study of health to the study of aging. Thus, in this research paper we focus on data from newly available data sets. Most of the very best new work was done in a multidisciplinary context; we draw our illustrations from these research teams.

Basic Facts about Today’s Aging Population

First, what is middle age like now? What is old age like now? In the following discussion we first answer these questions and then discuss how these new realities affect the study of health, behavior, and aging. Finally, we examine the question of which basic issues are important to a study of disease, health, and aging for the future development of this area.

Twenty-First Century Middle Age

An increasing life span is changing the concept of middle age. The ages from 40–60 years are clearly now middle-aged, because many people can reasonably expect to live to 80 to 100 and beyond. In 1995, the age-adjusted death rate for the total population reached an all-time low, and life expectancy at birth increased to 75.8 years, with a high of 79.6 years for White women (R. N.Anderson, Kochanek, & Murphy, 1997); put another way, 70% of people today will live to age 65—the normal retirement age—and 72% of deaths will come from persons over age 65 (Rowe & Kahn, 1998). This makes middle age a potentially different time of life from what it was only 25 years ago. Kaplan, Haan, and Wallace (1999) show how relatively recent this phenomenon is. “Between 1940 and 1995 life expectancy at birth increased 21% for females and 19% for males. Men and women who reach 65 can expect to live 15.7 and 18.9 years more; while life expectancy at age 80 has increased to 8.9 years for women and 7.3 years for men” (p. 90). Individuals now enter middle age under surveillance for diseases and are able to benefit from treatments that allow them to survive with many diagnoses that may not have any impact on their ability to function.

The explosion of interest in middle age is well represented in the collection of chapters in volumes edited by Lachman and James (1997) and Willis and Reid (1999). In terms of health, disease, and aging, the major topic for most middleaged persons is how to maintain health status as long as possible and how to put off old age. Successful aging really means not aging at all—or not appearing to have aged at all. Health psychology has been very successful at helping to determine the factors that predict disease onset in middle age and premature morbidity and mortality—now defined as below the average population age at death, which in the United States is around 75 years old. In fact, the same set of behavioral risk factors that are related to the onset of major chronic diseases (heart disease, cancer) also predict long-term disability-free survival (Siegler & Bastian, in press).

Bernice Neugarten’s (1974) term young-old (which divided the aging life cycle into two phases: 55–74 and 75 and older) has now become the expected rite of passage— refusing the old part of the young-old label entirely. However, it is important to recognize that successes in disease prevention in middle age make incidence of these same or related diseases higher later in life.

By midlife, health becomes important in definitions of self (Whitbourne & Collins, 1998), and bad health is a major feared possible self. Among middle-aged respondents, 67% versus 49% of the older respondents feared negative health changes (Hooker, 1999). Health threats can have an impact on coping, appraisal risk, and well-being (H. Leventhal et al., 1997). These changes in the boundaries of midlife are also reflected in survival differences that have implications for middle-aged persons—they are increasingly likely to have older parents and in-laws who require help with daily activities. These transfers of help across generations can take the form of time or of money and can have significant impact on both generations (Soldo & Hill, 1995). These experiences also have mental and physical health effects (Hooker, Shifren, & Hutchinson, 1992). Regardless of the relationship of the caregiver to the care recipient or the type of care recipient illness, the vast caregiving literature has shown that caregiving is associated with increased levels of distress, marital strain, and health problems among parents of children with chronic illness(Bristol,Gallagher,&Schopler,1988;Schulz&Quittner, 1998), family members of organ transplant patients (Buse & Pieper, 1990; Zabora, Smith, Baker, Wingard, & Cubroe, 1992), both children of dementia patients (Haley, Levine, Brown, & Bartolucci, 1987) and spouses of dementia patients (Vitaliano, Russo, Young, Teri, & Maiuro, 1991; Vitaliano et al., 1999; Vitaliano et al., 2002), reflecting the well-known factsthatpsychologicalstressislinkedtodisease(seeBaum& Posluszny, 1999).

Decisions about health made in midlife have long-term consequences. Women at around age 50, for example, must make decisions about hormone replacement therapy that may affect their risk of Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis in the future (Siegler et al., 2002). Furthermore, individual differences in personality predict risk behavior profiles, which also have long-term health consequences (Siegler, Kaplan, Von Dras, & Mark, 1999), personality also predicts just as do screening behaviors such as mammography (Siegler, Feaganes, & Rimer, 1995) and the use of hormone replacement therapy (Bastian, Bosworth, Mark, & Siegler, 1998; Matthews, Owens, Kuller, Sutton-Tyrell, & JansenMcWilliams, 1998).

A feature of middle age for women is the menopausal transition (Sowers, 2000), and the literature is starting to question endocrinechangesinmiddle-agedmen(Morley,2000).Anintriguing developmental question is whether age at menopause is a marker for rates of normal aging in women (Matthews, Wing, Kuller, Meilahn, & Owens, 2000, Perls et al., 2000), such that later menopause is a marker for longevity. Endocrine changes in men are more gradual than in women, but such changes are becoming an area of research interest (Morley, 2000; Tenover, 1999). Like estrogen levels, androgen levels decrease with age and have a broad range of effects on sexual organs and metabolic processes. Androgen deficiency in men older than 65 leads to a decrease in muscle mass, osteoporosis, decrease in sexual activity, and changes in mood and cognitive function—leading us to speculate that there may be at least two phases of chronic diseases related to androgen levels in men. Whether men over 65 would benefit from androgen replacement therapy is not known (Tenover, 1999). Any potential benefits from this therapy would need to be weighed against the possible adverse effects on the prostate and the cardiovascular system. Thus, considering men and women separately may be useful (Siegler et al., 2001).

Twenty-First Century Old Age

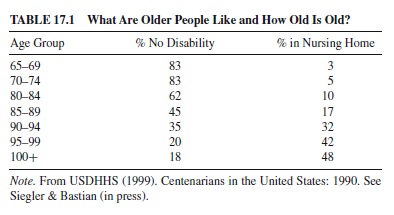

Let us remind ourselves of what we know—but that which is not obvious—about those known as “the elderly.” Anew emphasis on centenarians has meant that national statistics are now available up to age 100 and are often broken down more finely by age than they were before. The age of an older person provides some information about the probability of disability and the probability of living independently in the community; this can be seen in Table 17.1.

Note that until age 80, these indicators are reasonably stable for the older population—that is over 75% with no disability and less than 10% in institutions. We have known for a long time that institutionalization is a marker for the supporting network as much as it is for the functional capacities of the individual, at least until the person is no longer mobile or continent. By age 85, half are disabled. Although these figures vary by gender and other indicators, this is a reasonable guideline for thinking about current population statistics for today’s older population. The great variation in the population makes the design and interpretation of studies increasingly challenging.

Demographic projections suggest that rates of disability are declining (Manton, Corder, & Stallard, 1997) and that the gender ratio may be starting to move towards equalization in countries such as the United States due to efforts at prevention of cardiovascular heart disease (CHD)—benefiting men—and the long-term consequences of smoking in women (Guralnik, Balfour, & Volpato, 2000). However, most older people are women (E. Leventhal, 2000). There is evidence that women have different experiences with health and thus may report symptoms differently (E. Leventhal, 2000). Even when they have the same disease (such as a heart attack), the outcomes may be different (Vaccarino, Berkman, & Krumholz, 2000), and the perceptions of health-related quality of life also differ between men and women with the same disease (Bosworth, Siegler, Brummett, Barefoot, Williams, Clapp-Channing, etal.,1999;Bosworth,Siegler,Brummett,Barefoot,Williams, Vitaliano, et al., 1999).

Changes in Other Disciplines

Geriatric medicine is a branch of internal medicine that specializes in the care of older persons—particularly the oldest-old—and differs from developmental psychology in that it is unconcerned with adult development or midlife. Geriatric medicine is now a well-recognized discipline that has regular handbooks that update the new findings on each disease and its presentation in the elderly—with implications for treatment. The Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology (e.g., see Hazzard, Blass, Ettinger, Halter, & Ouslander, 1999) as well as the Encyclopedia of Aging (Maddox et al., 2001) have reasonable summaries of each disease and physiological system; the latter is a good reference for developmental psychologists, as are textbooks in gerontology, which provide reviews of physiological systems (e.g., Aldwin & Gilmer, 1999). Epidemiology looks at the distributions of disease in the population and is starting to consider age as more than a variable to be statistically controlled and a primary risk factor, whereas developmental epidemiology seeks to understand the role of age (see Fried, 2000; NIA Genetic Epidemiology Working Group, 2000). All of these Bibliography: are good primary sources for developmental psychologists who want to keep up with important developments in health-related fields.

Demographers are way ahead of psychologists in their thinking about the role of behavioral and social variables on survival and the role that age plays in such models. In particular,the detailed discussion—in a chapter by Ewbank (2000)— of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene polymorphism, which has implications for both Alzheimer’s disease and ischemic heart disease, is particularly useful. The paper discusses the contributions that genetics will make to demographic studies of aging and is a useful introduction to this complex and important set of issues for psychologists.

The Emphasis on Alzheimer’s Disease

One can not overemphasize the importance of the creation of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in 1974 and the push by NIA to develop the Alzheimer’s Centers programs. Research on basic biological mechanisms of the aging process is progressing at such a rate that from the time this research paper is written to the time it is published, this rate of new knowledge generation will have changed significantly what we know. The focus on Alzheimer’s disease has also had an impact on understanding cognition and aging so that the agerelated and disease-related components can be separated. Progress in developmental psychology does not happen at anywhere near the same rate, but developmental psychology must take into account the developing knowledge base in the biomedical sciences.

This emphasis has also produced some extraordinary studies with multidisciplinary teams of psychological, medical, and epidemiological sophistication; these teams are producing extraordinary data to answer important questions. Even better is that the results are being published in Psychology and Aging—our primary journal. Wilson, Gilley, Bennett, Beckett, and Evans (2000) provide an example of the type of research that sets a standard for the future. Their research asks the right questions, has compelling data, and was welldesigned to understand the role that age plays in the rate of change in cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Why is this study design so good?

This study (a) was based on a population sample of everyone with AD in the community under study; (b) had state-of-the-art diagnostic measures of the medical condition under study; (c) verified those measures; (d) had state-ofthe-art measures of the psychological factors under study; (e) collected repeated-measures data; (f) paid attention to study attrition and reasons for loss to follow-up; (g) used modern statistical methods—growth curve analyses to look at individual patterns of change—that allow for variations in measurement periods, missing data, and multiple measurements; and (h) asked and answered questions about initial level of cognitive functioning and the association of that level with eventual patterns of decline.

Approximately 400 persons with a diagnosis of AD were tested at yearly intervals for up to five repeated measures with a battery of psychometrically validated measures, including 17 key cognitive components of functioning changed in AD. The scales were combined into a composite such that raw scores were transformed to z scores and then averaged if at least eight of the scores were not missing. At the start of the study, individuals were aged 45–95 with a mean of 70.9 years, had graduated from high school, and were primarily female (67%) and White (85%). Mental status scores ranged from 11–29, excluding those with extremely impaired cognitive functioning.

The main results were that cognitive change was large, linear, and progressive (about one half of a standard unit per year). Those with better initial cognitive functioning changed more slowly, and younger persons declined faster than did older persons. Data were presented for estimates of the individualsstudiedandin5-yearagegroups.Whenthedatawerereanalyzed substituting changes in mental status with the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) a standard screening measure, the basic conclusions were the same: There was an annual loss of 3.26 points peryear, with bigger losses for those in their 60s than for those in their 80s. Of individuals who died during the course of the study, autopsy confirmed diagnosis in 96% of the cases.

In their discussion, Wilson et al. (2000) raised important issues that their study was not able to solve. These questions primarily had to do with how to address initial level of cognitive functioning. Everyone in the study had AD at the start of the study as a criterion for selection. Premorbid levels of cognition were not known. Similarly, age at first testing and age of onset of the disease could only be estimated by retrospective accounts of time of first symptoms. One could have started studying a very large population at age 40, conducted a 50-year study, and perhaps have had premorbid estimates of functioning and age at onset. Yet the design employed was an efficient way to help answer some important questions about the age-related nature of cognitive change in patients with AD.

The previously described study is not the only work in the field that meets these criteria—it is just one of the most recent and available in a single article, and a particular disease was of interest that is not considered a normal part of the aging process. The work of M. F. (Pete) Elias and his colleagues, combining insights from his longitudinal study of hypertension (M. F. Elias, Robbins, Elias, & Streeten, 1998) with work on the Framingham Study population (M. F. Elias et al., 2000; P. K. Elias, Elias, D’Agostino, Cupples, et al., 1997; M. F. Elias, Elias, D’Agostino, & Wolf, 1997; M. F. Elias, Elias, Robbins, Wolf, & D’Agostino, 2000), is also superb. In reviewing the role of age versus particular health conditions in the Framingham population, M. F. Elias et al. (in press) compared the adjusted odds ratios of performing at or below the 25th percentile on the Framingham neuropsychological test measurements controlling for education, occupation, gender, alcohol consumption, previous history of cardiovascular disease, and antihypertensive treatment. They found that age itself was the strongest factor—getting 5 years older increased the odds to 1.61 of performing at or below the 25th percentile on a battery of neuropsychological tests, compared to having Type II diabetes (1.21) or an increase in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm of mercury (1.30).

The M. F. Elias et al. (2000) data from the Framingham study were reanalyzed to answer two important questions: Does the impact of hypertension interact with age, and what is the practical significance of blood-pressure–related versus age-related changes? In addition, they reviewed findings from their longitudinal study of hypertensive and normotensive individuals (M. F. Elias et al., 1998). Their very careful analyses indicated that increasing age, increasing blood pressure, and chronicity of hypertension were all related to worse neuropsychological performance; there were no age interactions in these cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal data sets. The authors point to the methodological problem with longitudinal studies that do not have groups of nontreated hypertensive participants to follow over time. Thus, although it is clear that increased rates of hypertension are deleterious to cognitive functioning, it is important in future clinical trials that the impact of treatment on cognitive performance of older persons be monitored as well. For additional information, see Siegler, Bosworth, and Elias (in press).

Research examining the factors predicting cognitive decline is not limited to health factors. Fratiglioni, Wang, Ericsson, Maytan, andWinblad (2000) reported that social integration predicted the 3-year incidence ofAD in communitydwelling residents of a neighborhood in Stockholm, Sweden. The reason for their finding is unclear but provocative. It will be interesting to follow this cohort until it is depleted and see how many eventually become demented, at what age, and what role social participation plays in understanding the full process.

Health Status in Centenarians

The study of centenarians illustrates many important aspects of how studies of behavior, health, and aging have changed in the past 10 years. Table 17.1 shows the amount of disability that comes with increasing age; thus, longevity does not guarantee good health. This is surprising because most people expect that those who live until 100 should be in excellent physical and mental health. Increased survival does not amount to providing a disease-free old age for everyone.

Research reported in the Georgia and New England Centenarian Studies (Perls & Silver, 1999; Poon, Martin, Clayton, Messner, & Noble, 1992) seemed to indicate that those who survived to extreme old age tended to escape catastrophic disease episodes until they surpassed the average life span. If these findings are generalizable to other longlived individuals, then the trajectories of health and functioning over the life span would indeed be significantly different from those of the average population. For the long-lived, variations in health and cognition increased for participants in the Georgia Centenarian Study as well as for participants in the Swedish Centenarian Study (Hagberg, Alfredson, Poon, & Homma, 2001). The large within-group variation reflects the diversity and range of health and functioning in the oldest-old.

Estimates are generally that a third of extremely aged individuals are healthy enough to be independent and community dwelling, a third are functionally impaired, and a third are extremely frail and disabled (Forette, 1997). Franceschi et al. (2000) provides similar estimates (within 10%) from all of Italy, with criteria-based disease status and functional ability. The authors point out that the study of centenarians is a type of archeological research that includes social and historical circumstances over the past 100 years. Similar findings were reported by Franke (1977, 1985) on two centenarian samples in Germany. Western Europe has even greater proportions of older persons than does the United States, with 40% of the population expected to be over the age of 60 by 2030 (Giampoli, 2000). Studies of the full centenarian population are more common when measures of cognition are not required for study (see Jeune & Andersen-Ranberg, 2000; Poon et al., 1992); thus, past studies that focused on so-called expert survivors (Poon, Johnson, & Martin, 1997) may have given an overly optimistic picture of this age group.

Study and observation of centenarians are rare in the repertoire of life span researchers and gerontologists. The original data and papers were collected by Belle Boone Beard (1991), and comprehensive interview and testing video tapes of over 140 centenarians from the Georgia Centenarian Study are archived at the Hargrett Library of the University of Georgia. The material is available to all serious researchers who wish to pursue research on this important group of aging persons.

Longitudinal studies of aging can inform studies of the long-lived on predictors of survival. For example, the Alameda County Study (Breslow & Breslow, 1993) isolated seven health practices as risk factors for higher mortality. They are excessive alcohol consumption, smoking cigarettes, being obese, sleeping fewer or more than seven to eight hours per night, having very little physical activity, eating between meals, and skipping breakfast. These findings are very similar to those found in the Harvard College Alumni Study (Paffenbarger et al., 1993). The Dutch Longitudinal Study (Deeg, van Zonneveld, van der Maas, & Habbema, 1989) found that physical, mental, and social indicators of health status are important for predicting the probability of dying.

It is clear that there is strong agreement among longitudinal aging studies that maintenance of health, cognition, and support systems; a positive hereditary predisposition; and an active lifestyle are all influential in prolonging longevity in the general population. An important question is whether these same predictors are equally important for the very longlived—for example, those whose longevity extends beyond 100 years. There are very limited data that could address this question. Poon et al. (2000) examined survival among a group of 137 centenarians (75.9% women) who participated in the Georgia Centenarian Study, of whom 21 were still alive at the time of the investigation in 1999. They found the following relationships among characteristics of centenarians and length of survival beyond 100 years:

- Women on the average survived 1,020 days after attaining 100 years. Men, on the other hand, survived an average of

- 781 days. The gender difference in survival in the first 2 years after 100 is not significantly different; however, the difference is quite glaring after 3 years.

- Father’s age at death was found to exert a positive effect on the number of days of survival after 100 years. No effect was found for mother’s age of death.

- Three variables in social support seem to relate to length of survival among centenarians. They are talking on the phone, having someone to help, and having a caregiver.

- Four anthropometric measures were found to correlate positively to survival. They are triceps skin fold, body mass index, and waist-to-hip ratio.

- Higher level of cognition after 100 was positively related to longer length of survival; this was found for problem solving, learning and memory, and intelligence tests, such as picture arrangement and block design. In this study, gender, family longevity, social support, anthropometry, and cognition all seemed to impact on survivorship after 100 years.

Within centenarians, it is clear that variation is extraordinary in health just as in most other characteristics mentioned. There are special problems associated with studying psychological characteristics in the full centenarian population. Poon et al. (2000) demonstrated the effects of attrition in longitudinal studies of centenarians. If attrition and patterns of attrition are not accounted for in the analyses, the outcome would essentially focus on the survivors—and this would not be representative of the entire population. In this study, attrition seemed to affect different psychological measures differently. In cognition, for example, fluid intelligence seems to be affected more by attrition than is crystallized intelligence.

Data from the Cardiovascular Health Study evaluated 5-year survival from ages 65–101 at baseline (Fried et al., 1998) in almost 6,000 persons, including both White and African American participants. The participants were wellcharacterized medically for both clinical and subclinical measures of health status and standard CHD risk factors. In addition, depressive symptoms were assessed by the Center for Epidemologic Study Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), cognition with the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975), and the Digit Symbol Substitution task of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS). Participants were reinterviewed every 6 months and had been followed for 5 years at the time of the article. Individuals from four communities in the United States were identified by random sample from the Health Care Financing Administration, and 57% of the sampled individuals participated. Mortality follow-up was complete for 100% of the sample. There were 646 deaths— 12% of the population had died in 5 years. The effect of age on mortality was greatly reduced by adjusting for other demographic, disease, behavioral, and functional indicators. The effect of age on mortality became substantially weaker with adjustment coded into the prediction equation than when it was analyzed in isolation. Digit Symbol Substitution remained a significant predictor even after adjustment for everything else, including objective measures of both clinical and subclinical disease. Thus, much of the effect of age on mortality is explained by the other disease and personal characteristics. If it were not for the diseases and health habits, people would live longer.

Genetics Revolution

The genetics revolution affects the study of psychology of aging in two important ways. First, as the source of individual differences, understanding genetic polymorphisms, how they relate to behavior, and how these then change with age becomes critical. Secondly, the genetics of survival and longevity are a major concern of understanding the biology of aging and of gender differences, which have changed over time and need to be taken into account as the background for theories about life span development and aging.

Although answers to the preceding two sources of genetic influences on behavioral aging are still to be found, McClearn and Heller (2000) provide an interesting explanation of how to assess the literature in this area. They point out that at different ages, the relative contributions of genetic and environmental variance in important characteristics may change— this is a new way of thinking about genetic variation. It is generally assumed that after a genetic marker is known, it will be a stable individual difference characteristic.Although genes are fixed at birth, they can have different effects at different ages, interact with environments differentially at different ages, and behave differentially in different populations. There are age-related changes in heritability—that is, the amount of variance in a population due to genetic variance. In addition to age-related changes in heritability, it is quite possible that different genes or different combinations of genes are operative at different parts of the life cycle. Illustrations from the Swedish/Adoption Twin Study ofAging for understanding stability of personality are given by Pederson and Reynolds (1988), and a discussion of patterns for three cholesterol indicators is given by McClearn and Heller (2000).

Together, these data sets illustrate the complex interactions of genes and environment over the adult life cycle. As more and more data become available that attest to the geneenvironment interactions across the life cycle, we will be better able to make use of them. To extend this line of thinking further, issues of longitudinal stability and change may be affected or interpreted differently when both genetic and environmental factors are included over time (Pederson & Reynolds, 1998).

The genetic basis of longevity has not been part of developmental psychology. The literature has yet to successfully partial out the influences of genetics and environment on longevity and behavioral aging. However, findings from centenarian studies could begin to shed light on some of these issues. For example, findings from the French Centenarian Study (Robine, Kirkwood, & Allard, 2001) showed a tradeoff of fertility and longevity—that is, women who bear no or few children tend to live longer. Does the lower-stress environment of fewer children contribute to longevity, or is there a genetic predisposition to protect women with fewer children in order to decrease stress?

In the Georgia Centenarian Study (Kim, Bramlett, Wright, & Poon, 1998), gender and race were found to combine to influence longevity after 100. African Americans showed longer survival times than did European Americans, and females (as noted earlier) showed increased survivorship in comparison to males. At any given time, the risk of death for women was only 54% of that of men. Likewise, risk of death for African Americans was 57% of that of European Americans at any given time.The order of increasingly longer survival for sex-race subgroups was European American males,AfricanAmerican males, EuropeanAmerican females, and African American females. These findings suggest that the differentiation of genetics and environmental influences would help us better understand the impact of race and gender on longevity. Similarly, the Georgia study found that higher levels of cognition are related to longer life—and that among the independent centenarians, everyday problem-solving abilities seemed to be maintained (Poon et al., 1992).

Does experience acquired over one’s lifetime help to buffer and maintain problem-solving abilities, which in turn help the individual live longer? These are intriguing questions that could add a new dimension to the study of developmental psychology.

Some Basic Conceptual Issues

As our population continues to age, a better understanding of how disease, health, and aging are interrelated becomes all the more important—and more difficult to measure and understand. Health is an odd concept. It does have psychological meaning to individuals and to developmental psychologists. It is not the inverse of disease and it also has a developmental trajectory and importance. How it is defined makes a major differences in the conclusions about health and aging. It is important to remember that health is often defined from the research participants’(not the researchers’) perspective.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

HRQoL has been defined as a multidimensional concept that includes the physical, mental, and social aspects of health (e.g., Sherbourne, Meredith, & Ware, 1992). HRQoL is important for measuring the impact of chronic disease (Patrick & Erickson, 1993). There is evidence of great individual variation in functional status and well-being that is not accounted for by age or disease condition (Sherbourne et al., 1992). HRQoL is typically conceptualized as an outcome of psychological and functional factors that individuals ascribe to their health.

We have completed a series of studies using a measure of HRQoL using the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36; Ware, 1993). The specific item that most investigators use to measure health is the question How do you rate your health? Excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor? This is also a question on the SF-36 in the domain of General Health and could be considered the SF-1. The SF-36, the complete HRQoL measure, has proven to be very useful to evaluate a patient’s perspective as a medical outcome and is typically scored as eight scales.

The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item SF-36 is a Likert-type or forced-choice measure that contains eight brief indexes of general health perceptions, general mental health, physical functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, limitations in social functioning because of physical health problems, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, and vitality. These indexes have been factored into two overall measures of physical health and mental health.

Our work has been based on a sample of patients referred for coronary angiography; the patients can be separated into those with and those without significant heart disease. Coronary angiography is a surgical procedure used to determine how much stenosis or blockage exists for the major arteries. This group is an interesting sample to study because their actual disease and physiological status have been measured and can be used to control for physical health or disease status. Our work was designed to find out why and how social support can moderate the effects of disease; it followed our report that social support and income predicted mortality from coronary heart disease when actual physical health was accounted for (Williams et al., 1992).

All patients referred to Duke University Medical Center for an evaluation of their symptoms to see whether they had blocked arteries (1992–1996) were invited to be in the study upon admission and given a large battery of psychosocial instruments. Those without coronary artery disease were not studied further. Those with disease were followed for the next 3 years with repeated assessments—including the SF-36—of psychosocial factors. The Duke Cardiovascular Database follows all coronary patients at Duke for assessment of future disease and mortality (Califf et al., 1989). Understanding the characteristics of the sample is important because it allows us to ask some questions from an aging point of view such that we can evaluate younger and older persons with the same disease and see whether psychosocial factors play the same role in younger and older patients.

We looked at the relationship between social support and HRQoL in this sample and observed that a lack of social support was associated with significantly lower levels of HRQoL across all eight SF-36 HRQoL domains after considering disease severity and other demographic factors. We also observed an interesting relationship between age and HRQoL. Older adults were likely to experience lower levels of physical function and physical role function; however, older adults were also more likely to report higher levels of mental health, emotional role function, and vitality compared to younger adults (Bosworth, Siegler, et al., 2000). A possible explanation for this finding is that older patients show mental health better than that of younger patients with similar diseases because the onset of chronic illness in old age is more usual and—subsequently—possibly less disruptive than in younger adults. In addition, older persons may have developed more effective skills with which to manage health deficits (Deeg, Kardaun, & Fozard, 1996). These two points coincide with Neugarten’s (1976, 1979) view that the onset of chronic illness in old age is more usual in that part of the life cycle and therefore possibly less disruptive. Subsequently, as individuals lose physical function, they may focus and channel more of their energy and attention on the maintenance of psychological quality of life.

Self-Rated Health (SRH)

After Mossey and Shapiro (1982) found that self-ratings of health (SRH) were predictive of 7-year survival among older adults, there has been an enhanced interest in the use of SRH (usually measured by asking respondents whether they would rate their health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) as ameasureofhealthstatus.Thisinterestamongresearchershas grown because this item is easy to administer to large populations, and it captures perceptions of health by using criteria that are as broad and inclusive as the responding individual chooses to make them (Bosworth, Siegler, Brummett, Barefoot, Williams, Vitaliano, et al., 1999).

SRH is a specific component of HRQoL and reflects more than the individuals’ perceptions of their physical health. Psychological well-being also is a relevant factor in SRH (George & Clipp, 1991; Hooker & Siegler, 1992). For example, some researchers have suggested that SRHs reflect a person’s integrated perception of his or her health—including its biological, psychological, and social dimensions—that is normally inaccessible to other observers (Mülunpalo, Vuori, Oja, Pasanen, & Urponen, 1997; Parkerson, Broadhead, & Tse, 1992; Ware, 1987)

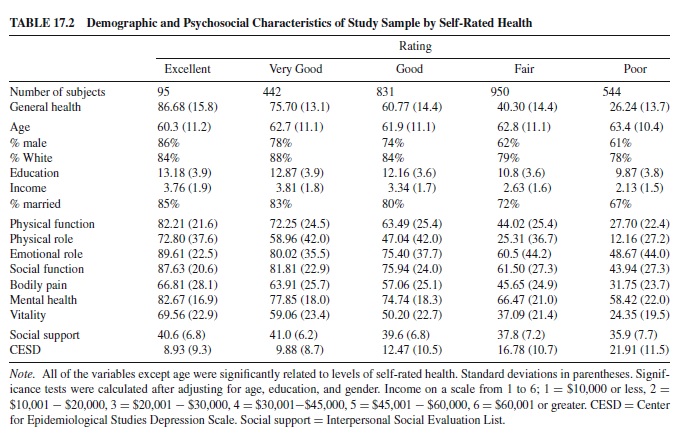

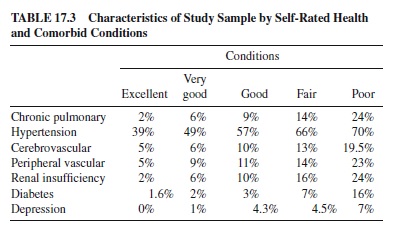

This sample of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) has both medically determined and self-perceived ratings of health. It is a particularly interesting group to study because we can help explain the import of SRH measures and how to interpret the single-item index in the context of aging persons who are well-characterized in terms of their actual health-disease status. Some data from this sample are presented in Table 17.2, which shows demographic indicators, the functional scales of the SF-36, and two psychosocial indicators. Table 17.3 shows the other medical conditions present in this population.

The data show that when restricted to the 2,900 persons (ranging in age from 28–93) who had serious and significant coronary artery disease, people rated their health all along the SRH continuum from excellent (3%) to very good (15%) to good (29%), to fair (33%), and poor (19%). The average age of each subgroup ranged from 60 to 63.4 years. These findings can be compared to national figures from 1996, in which the percent of the U.S. population that rated their health as fair or poor aged 55–64 was 21.2% and aged 65 and over was 27% (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1999, p. 211, Table 60). In our sample of a wider age range, with significant heart disease, by comparison, 52% rated their health as fair or poor.

Thus, in a sample with documented serious heart disease, the rate of fair or poor health was twice as high as in a national population sample of the same age. These levels were associated with the hazard score (Harrell, Lee, Califf, Pryor, & Rosati, 1984), an index of age and disease severity that captures the probability of 1-year survival (90% at excellent to 75% at poor). For comparison purposes, at baseline, in the University of North Carolina Alumni Heart Study, which started in 1986 (Siegler et al., 1992), among middle-aged persons unselected for health at age 40, 57.3% rated their health as excellent and 39.3% as good. Four years later the ratings were 53.2% excellent and 43.4% good, with 2.8% and 3.4% fair and poor, respectively (Siegler, 1997).

Thus, as a single item, the measure is easy to implement and has predictive validity. It is also predictive of mortality in a wide variety of populations (Bosworth, Siegler, Brummett, Barefoot, Williams, Clapp-Channing, et al., 1999a; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Idler & Kasl, 1991; Kaplan & Camacho, 1983; Mülunpalo et al., 1997; Mossey & Shapiro, 1982; Wolinsky & Johnson, 1992). Self-rated health captures a lot of summary information about health status, but it does not represent the specific disease status of an individual. Note that even those who say they are in excellent health with major heart disease have comorbid conditions (as shown in Table 17.3), are not clinically depressed, and do not see their disease as affecting their ability to function on a day-to-day basis.

Thus, although the findings reported here do support the importance of assessing SRH, it is not synonymous with disease. Second, global SRH tends to reflect to a large degree those health problems that are salient for study participants. SRH measures are often used as covariates in examinations of the effect of age. An important question that needs to be answered is what it means to use a single measure of health status as a covariate. Although physical and mental health problems appear to play a major role in shaping an individual’s perception of his or her health, a significant proportion of what this single-item indicator explains remains unknown. Treating health status as a covariate reduces the variance associated with age. SRH also reduces the variance due to depression and is differentially associated with gender, race, income, and education. Despite the increased interest among researchers in the use of SRH as a measure of health, it is still unclear how this item relates to health and well-being and how clinicians can use this measure.

One way this item may be used by clinicians is to predict health care utilization. Bosworth, Butterfield, Stechuchak, and Bastian (2000) examined whether SRH predicted health service use among women in an equal-access primary care clinic setting. Women who had poor or fair health were significantly more likely to have more outpatient clinic visits than were women who reported excellent or very good health. Bosworth, Butterfield, et al. (2000) concluded that these findings demonstrate the potential of a single question to provide information about the future needs for health care. The fact that self-rated health was not related to age in our clinical population is an interesting observation that requires some comment. It may reflect the fact than when younger individuals have the same disorder as older individuals, it is generally more serious in younger persons; or it may reflect age-related differences in expectations. The other interesting observation that has not been well documented is a phenomenon referred to as a response shift (Sprangers & Schwartz, 1999). Patients confronted with a life-threatening or chronic disease are faced with the necessity to accommodate to the disease. A response shift is potentially an important mediator of this adaptation process; it involves changing internal standards, values, and conceptualizations of quality of life (Sprangers & Schwartz, 1999). Potential age differences in response shifts may explain why it is not uncommon to observe an 80-year-old man who recently underwent coronary bypass surgery as reporting that his health is excellent.

In sum, some guidelines may be proposed for using health measures. First, although the findings reported here do support the importance of assessing SRH, it is not synonymous with disease. Second, global SRH tends to reflect to a large degree those health problems that are salient for study participants. Third, in order to make correct attributions about normal development and behavior change expected under specific conditions and specific ages, developmental psychologists need to learn to verify self-reports of diseases and also include hard disease outcomes such as blood pressure or ejection fraction. Verification of diseases can be very instructive. Medical criteria are not always uniform, which is why epidemiologists obtain actual medical records and code to criteria. As developmental psychologists, we need to know what it is like to age with each disease and each condition, as well as what it is like for those who are fortunate enough to age without them. To accomplish this recommendation, developmental psychologists need to develop long-term collaborative research programs and work with investigators who understand the pathophysiology of the disease process being studied.

In order to better interpret studies that use SRH, it is important to remember that (a) these findings will have an socioeconomic status (SES) gradient related to timing and quality of medical care such that a more severe disease profile will tend to be seen earlier in the life cycle in the disadvantaged (N.A.Anderson &Armstead, 1995; House et al., 1992); (b) the reports will be related to cognitive status because individuals need to remember what the diagnosis is to be able to report it; (c) the reports will be related to psychological symptoms because individuals are more likely to seek medical care if symptomatic (Costa & McCrae, 1995); (d) the self-rated measures will be more highly correlated with psychosocial constructs that are also associated with the same underlying dimensions of personality.

Other Approaches to Measuring Health

Most other approaches used to measure health in psychological research are really measures of disease that require the input of medical colleagues for a diagnosis or an understanding of medical records that can be reviewed and characterized (see E. Leventhal, 2000); in addition, they may be a combination of physiological indicators and medical records reviews (see Vitaliano, Scanlan, Siegler, McCormick, & Knopp, 1998). Zhang, Vitaliano, Scanlan, and Savage (2001) present data on the associations of SRH, biological measures, and medical records in their longitudinal study of caregivers. Self-reports of heart disease were moderately correlated with heart disease diagnoses from the medical records (r = .64), which is significant but not comforting. Self-reports of heart disease and biological indicators (e.g., lipids, blood pressure, insulin, glucose, and obesity) were uncorrelated, whereas these same measured indicators were significantly correlated with the medical record reports of disease. In a principle components analysis, SRH loaded on a component with the other psychosocial measures (anxiety, depression, life satisfaction), whereas the biological measures loaded on a component with the medical records.

Many developmental psychologists measure disease by simply asking patients whether they have or had a particular disease. Although this information is easy to obtain, it is important to realize the potential for patients to not recall having the particular disease or not wanting to report having had the particular disease. A case in point was recently reported by Desai, Livingstone, Desai, and Druss (2001), who examined the accuracy of self-reported cancer history. The authors compared self-reported responses in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Study and were linked to the Connecticut Tumor Registry—the overall rate of falsenegative was 39.2%. Non-European Americans, older adults, increased time since cancer diagnosis, number of previous tumors, and type of cancer treatment received were all related to increased likelihood of not reporting having had a tumor. Thus, despite developmental psychologists’ and epidemiologists’using self-reported data about disease, it is important to determine the validity of these reports when possible.

Medical Comorbidity

A relatively unique characteristic of older populations is the coexistence of several chronic conditions. Among persons aged 65–101 at baseline in the Cardiovascular Health Study, 25% had one chronic condition and 61% had two or more chronic conditions (Fried et al., 1998). The tendency has been to construct scales that add up all comorbid conditions (Charlson, Szatrowski, Peterson, & Gold, 1994). This approach may allow a general assessment of chronic disease burden and can be predictive of broad patterns of mortality outcomes; but the process of combining conditions into a single scale obscures considerable pathophysiological detail that may have etiological importance. In addition, simply adding up the number of comorbidities ignores the variability in severity of a particular disease. Patients may vary in the effects of the same disease. For example, patients may have one of four stages of congestive heart failure (New York Heart Classification 1–4) or one of three stages of cancer (local, regional, and distance). In addition, simply adding up the number of comorbidity factors assumes that two diseases have the same impact on patients. For example, most clinicians would argue that experiencing a stroke or a myocardial infarction is more severe than experiencing arthritis, although the resultant disability may vary.

In our own studies in which we examined the relationship between SRH and various comorbid illnesses (see Table17.3), we observed that various diseases and disorders examined varied in their association with SRH. Stroke, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder were all found to be related to poorer SRH. However, 12 of the other 19 comorbid illnesses were not significantly related, including abdominal aortic aneurysm, thoracic aortic aneurysm, dialysis-dependent renal failure, cancer, substance abuse, depression, arthritis, back pain, peptic ulcer, hepatitiscirrhosis, and myocardial infarctions. Thus, using a summated comorbidity measure, as commonly used, assumes that each disease is equally influential in affecting whatever the outcome may be. Summation of comorbidities does not consider the variations in prevalence and incidence of diseases, nor does it consider—more important—the severity of diseases (Bosworth, Siegler, Brummett, Barefoot, Williams, Vitaliano et al., 1999b).

Psychiatric Comorbidity and Aging

When considering health, disease, and aging, depression is a particularly important comorbidity that needs to be considered. Medically ill patients often suffer from depression. Depression is common among coronary heart disease patients (Brummett et al., 1998; Carney et al., 1987; Forrester et al., 1992; Hance, Carney, Freeland, & Skala, 1996; Schleifer, Macari-Hinson, & Coyle, 1989) and is predictive of rehospitalization(Levineetal.,1996)andincreaseddisability(Ormel et al., 1994; Steffens et al., 1999). Depression during hospitalization following a myocardial infarction (MI), for example, predicts both long- and short-term survival rates (Barefoot, 1997; Frasure-Smith, Lesperance, & Talajic, 1993).

Depression has consistently been implicated in the causal web of incident disability and of functional decline in population samples (Stuck et al., 1999). Major depressive disorder (MDD), minor depression, and depressive symptoms have each been associated with functional disability. Depression and physical function are intertwined; a feedback loop exists such that depression causes increased disability and increased disability exacerbates depression. Similarly, medication adherence among depressed older persons is poor, and this feedback loop exists such that depression causes nonadherence with medical treatment and nonadherence further exacerbates depression so that a focus on both is essential (DiMatteo, Lepper, & Croghan, 2000). DiMatteo et al. (2000), for example, reported that the relationship between depression and nonadherence was significant and substantial, with an odds ratio of 3.03 (95%; 1.96–4.89).

Depression may increase nonadherence with treatment for multiple reasons. First, positive expectations and beliefs in the benefits and efficacy of treatment have been shown (DiMatteo et al., 1993) to be essential to patient adherence. Depression often involves an appreciable degree of hopelessness, and adherence might be difficult or impossible for a patient who holds little optimism that any action will be worthwhile. Second, considerable research (DiMatteo & DiNicola, 1982; DiMatteo, 1994) underscores the importance of support from the family and social network in a patient’s attempts to be compliant with medical treatments. Often accompanying depression are considerable social isolation and withdrawal from the very individuals who would be essential in providing emotional support and assistance. Third, depression might be associated with reductions in the cognitive functioning essential to remembering and following through with treatment recommendations (e.g., taking medication).

Caregiving as a Threat to Health

Depression is often an outcome of studies of stress and aging. This is well represented by the caregiving literature. Two recent special issues (Vitaliano, 1997; Schulz & Quittner, 1998) give an indication of the types of studies that have been done.WorkbyVitalianoandcolleaguesshowsthatthestressof caregiving also has significant effects on measures of physical health status when indexed with medical records—and with (a) biological indicators of the metabolic syndrome (Vitaliano et al., 1998) and (b) measures of immune system functioning and sleep disturbance (Vitaliano et al., 1999). These relations are found both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. It is also most interesting that women who use hormone replacement therapy (HRT; both caregivers and controls) are better off physiologically than their counterparts who do not use HRT (Vitaliano et al., 2002); Whether this is another example of (a) the so-called healthy woman effect, wherein women who have a risk profile that reduces disease are more likely to take HRT; (b) the effect of estrogen (see Matthews et al., 2000); or (c) the effect of some additional mechanisms is not clear. Nevertheless, this is an observation that should be pursued.

Life tasks are made harder when health problems are present. Multiple problems require more complex management of medications, and increasingly complex decisions about care choices need to be made. Not only are the problems to be solved more complex, the cognitive capacities of the older person may not be operating at peak efficiency (Peters, Finucane, MacGregor, & Slovic, 2000). One solution suggests that there is a greater need for intergenerational collaboration in decision making. When family members are available, this becomes part of the caregiving task. As increasing numbers of older persons have fewer siblings and children than do current older persons, new solutions will need to be found to deal with difficulties in decision making among the elderly.

Methodological Considerations

In the study of health and disease, two particular methodological issues are worthy of note: (a) the role of period effects and (b) selection effects from study designs that sample the actual age distribution of the population versus those that oversample the oldest old.

Period Effects of Disease Detection and Treatments

A period effect or time effect is a societal or cultural change that may occur between two measurements that presents plausible alternative rival explanations for the outcome of a study (Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroade, 1988; Schaie, 1977). Studies have often focused on cohort and aging effects, but there has been a lack of focus on period effects that may explain observed age changes in longitudinal and age differences in cross-sectional studies that examine the relationship between health, behavior, and aging (Siegler et al., 2001). In addition, period effects may affect the prevalence and incidence of disease.

As discussed elsewhere (Siegler et al., 2001), the introduction of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test is an example of the effects of period-time effects accounting for changes in the detection of prostate cancer.APSAtest is a diagnostic tool for identifying prostate cancer, and since its introduction in 1987 there have been increasing numbers of prostate cancers being diagnosed among older adults that would not have been diagnosed based upon previous techniques (Amling et al., 1998). Subsequently, there has been an observed increase in number of prostate cancer diagnoses, and because prostate cancer prevalence rates increase with age, researchers studying longitudinally the relationship between age and onset of prostate cancer would have to account for the introduction of this relatively new diagnostic tool.

Information is being made available more quickly and improvements in diagnostic techniques and treatments are increasing in frequency. This is a benefit for the population, but it makes research more difficult, particularly if an intervention is in process and new information or changes in medical procedure are being made available to the public at large. Subsequently, developmental psychologists and other researchers are going to have to become more aware and flexible in the way they deal with these increasing periodtime effects.

An example of researchers who are adapting to historical or period effects is the ongoing Women’s Health Initiative Study, in which information on estrogen use is being collected. There have been increased data that suggest the influence of estrogen is related to long-term benefits such as prevention or delay of osteoporosis, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease (Jacobs & Hillard, 1996), but recent information about raloxifene and tamoxifen have altered women’s perception of the use of hormonal replacement medication.

News of health and aging has been gaining more public attention, which also needs to be considered in both crosssectional and longitudinal studies of aging, health, and disease. Thus, the context in which the study was conducted now must be better characterized. One example comes from our own research, in which we conducted telephone interviews between October 1998 and February 1999 among a random sample of women aged 45–54 residing in Durham County, North Carolina. Women were recruited for a randomized clinical trial to test the efficacy of a decision aid intervention on HRT decision making. One of the factors that determines HRT use and influences HRT decision making has been the cardio-protective effects of HRT. However, an influential publication in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicated that women using HRT in the short term were at a increase risk for CHD events (Hulley et al., 1998). Although limited data are available at this time, our study and others looking at HRT decision making are likely to be influenced by these recent results.

Selection Effects

Individuals at higher risk for mortality, morbidity, physical function, and so on may be selected out of the populations at earlier ages.Although this selection applies to any age cohort, the forces of proper selection are much stronger in older populations.The analysis of the consequences of selective survival is complex and can lead to a variety of age-related patterns in differential survival (Vaupel & Yashin, 1985). It is useful to think of three ways in which selective survival might influence age-related trends in risk factor-outcome associations. If those with a particular risk factor experience higher and earlier mortality, then the distribution of risk factors in the survivor population would be altered relative to the original distribution and should reflect lower levels of risk factors (i.e., less likely to smoke, be overweight). This would occur because those with high levels of risk factors are more likely to have been removed from the population. Second, it is possible that there are unmeasured differences in susceptibility to the risk factor among both those previously exposed and those unexposed. Third, the survivors may have other characteristics—genetic or environmental in origin—that prevent or slow the progression of disease, shifting the onset to a later age. Thus, it is important to consider survival effects when conducting research on health and aging.

Conclusions and Future Directions

There were a series of old questions that were always part of the chapters written about aging and health (e.g., see Eisdorfer & Wilkie, 1977; M. F. Elias, Elias, & Elias, 1990; Siegler & Costa, 1985). These old and current questions and answers include the following:

- Do variations in physical health account for aging effects? Not necessarily; it really depends on the age group studied. New data in centenarians are changing our understanding of these relationships.

- Is there such a thing as normal aging? No. It is a moving target, changing with each new publication.

One explanation for this change is period effects—that is, changes such as improved survival of persons with coronary heart disease influence the definition of normal aging. These changes in survival are due to medical interventions such as angioplasty and coronary artery bypass surgery, which are increasingly made available to older persons with heart disease. How we die is different from what was the case when previous chapters addressing these questions were published. More people now die later in life when the cause may not be due to a specific disease (Fried et al., 1998; Nuland, 1995).

Does this situation mean that there is no longer a need for developmental psychology to be concerned with health? No—we now have new opportunities to consider along with a tremendous base of work on which to stand. Work is underway in all of the following areas.

How should researchers measure the important psychological constructs in everyone who is aging—that is, how they measure psychological constructs for extremely aged persons or those with exceptional longevity? Developmental psychologists know that there is great variation in mental and physical healthstatusandinsensoryandmotorcapacities.Untilwecan fully measure psychological factors in everyone, we cannot understand these factors completely.

Now that epidemiology and geriatric medicine are measuring disease in the elderly and extreme aging population, we needpsychologicalmeasuresdesignedtobeusedinlaboratory settings that are associated with disease outcomes and biological indicators. The discussion in Finch, Vaupel, and Kinsella (2000) provides an instructive discussion of this issue.

We also need to continue to develop and validate psychological measures that are appropriate and valid in survey research. Burkhauser and Gertler (1995) describe the Health and Retirement Study, Herzog and Wallace (1997) lay out the issues for the Asset and Health Dynamics of the Oldest-Old Study, while Zelinski et al. (1998) provide an example of the strengths and weaknesses of current approaches. Additional development will require some basic psychometric work for age, content, and size of scales that measure important psychologicalconstructs.Thisdevelopmentwillrequiresome basic psychometric work for age, content, and size of scale. We know the problems but not the solutions. We also need to conceptualize health in ways that make sense psychologically. Self-rated health is a good single item, but can we do better (Kennedy, Kasl, & Vaccarino, 2001)? How do we measure well-being when health is completely compromised? This is an area of research that Powell Lawton started (1997) and unfortunately did not live long enough to complete. He called for a valuation of life that is possible in all health status configuration.

Reevaluate a life span approach. Our life span may have been too conservative, given the data by Kuh and Ben Shlomo (1997) wherein infant and prenatal variables predicted adult onset of disease and adult health, whereas mid-life variables appeared to have no relevance to geriatric syndromes.

Make psychology relevant to important concerns in economics and public policy. Health disparities due to social class, race, and ethnic differences do not disappear with age. The disparity is real and we do not know the causes. How much variability could genetics contribute to resolve the disparity? Is it related to life course exposures?Are there critical periods at various points in the lifecycle? In 1999, Health, United States (USDHHS, 1999) picked aging as its special topic for the year, as “older people are major consumers of health care and their numbers are increasing” (p. iii). Some highlights of the report are worth noting: (a) By 2030, 20% of the U.S. population will be over age 65; (b) life expectancy at age 65 and at age 85 has increased over the past 50 years—at age 65 European Americans have a higher life expectancy, whereas at age 85 African Americans have a higher life expectancy; however, health disparities by race are shocking. Mortality rates are 55% higher for African Americans—ageadjusted death rates were 77% higher for stroke, 47% higher for heart disease, and 34% higher for cancer. In an important sense, these mean fundamentally that lower SES persons appeartoagefaster—thatis,thingsthathappenlaterinthelife cycle for those further up the SES ladder happen earlier for those on the bottom of the ladder. Trying to fully understand what this means is a major challenge for our field.

Developmental psychologists know a lot about aging processes and measurement and are interested broadly in all aspects of human development. However, for the study of health and disease to progress, investigators must conduct research in conjunction with research teams expert in all aspects required to solve particular problems. Other disciplines and other countries are well ahead of us on this problem. What can we contribute as developmental psychologists?

Responding to the fears of the public and policy makers about the explosion of aging in the population, Carstensen in a New York Times editorial (2001) rightly points out the opportunity to design a new stage of life. She argues that not all aging changes need to be bad. She assumed that medical and psychological science will solve the problems of the elderly today and find a cure for frailty that is not necessarily disease-related. We may have reached Fries’s (1980) compression of morbidity, where function is preserved until the final 1, 3, or 5 years of life. After most of the population gets there, what will happen with health maintained until the ninth decade?

We have the knowledge to improve the odds and postpone the deleterious consequences that had previously been attributed to normal aging or even to disease-related aging. Worldwide studies of centenarians and supercentenarians are seeking answers as to what determines the characteristics that lead to 110 years of disability-free life? The simpleminded answer of preventing disease is probably not going to be the correct one. The real future challenge is to figure out how to ask the right questions. Health will play an increasingly important role for developmental psychologists, and—as changes in health care and the demographic revolution continue to occur—we need to be able to include contextual influences and period changes in order to better understand the role of health and disease among older adults.

Bibliography:

- Aldwin, C. M., & Gilmer, D. F. (1999). Immunity, disease processes and optimal aging. In J. C. Cavanaugh & S. K. Whitbourne (Eds.), Gerontology: An interdisciplinary perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Amling, C. L., Blute, M. L., Lerner, S. E., Bergstralh, E. J., Bostwick, D. G., & Zincke, H. (1998). Influence of prostatespecific antigen testing on the spectrum of patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy at a large referral practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 73, 401–406.

- Anderson, N. A., & Armstead, C. A. (1995). Toward understanding the association of socioeconomic status and health: A new challenge for the bio-psychosocial approach. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 213–225.

- Anderson, R. N., Kochanek, K. D., & Murphy, S. L. (1997, June). Report of final mortality statistics. Monthly Vital Statistics Report, 45(11), Supplement 2.

- Baltes, P. B., & Mayer, K. U. (Eds.). (1999). The Berlin Aging Study: Aging from 70–100. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Baltes, P. B., Reese, H. W., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1988). Introduction to research methods: Life-span developmental psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Barefoot, J. C. (1997). Depression and coronary heart disease. Cardiologia, 42, 1245–1250.

- Bastian, L. A., Bosworth, H. B., Mark, D. B., & Siegler, I. C. (1998, November). Are personality traits associated with the use of Hormone Replacement Therapy in a cohort of middle aged women undergoing cardiac catherization? Paper presented at the meetings of the Gerontological Society of America, Philadelphia, PA.

- Baum, A., & Posluszny, D. M. (1999). Health Psychology: Mapping biobehavioral contributions to health and illness. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 137–163.

- Beard, B. B. (1991). Centenarians: The new generation. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bosworth, H. B., Butterfield, M. I., Stechuchak, K. M., & Bastian, L. A. (2000). The relationship between self-rated health and health care service use among women veterans in a primary care clinic. Women’s Health Issues, 10(5), 278–285.

- Bosworth, H. B., Siegler, I. C., Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Williams, R. B., Clapp-Channing, N., Lytle, B. L., & Mark, D. B. (1999). Self-rated health as a predictor of mortality in a sample of coronary artery disease patients. Medical Care, 37(12), 1226–1236.

- Bosworth, H. B., Siegler, I. C., Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Williams, R. B., Vitaliano, P. P., Clapp-Channing, N., Lytle, B. L., & Mark, D. B. (1999). The relationship between self-rated health and health status among coronary artery patients. Journal of Aging and Health, 13(4), 565–584.

- Bosworth, H. B., Siegler, I. C., Olsen, M. K., Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Williams, R. B., Clapp-Channing, N., & Mark, D. B. (2000). Social support and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Quality of Life Research, 9(7), 829–839.

- Breslow, L., & Breslow, N. (1993). Health practices and disability: Some evidence from Alameda County. Preventive Medicine, 22(1), 86–95.

- Bristol, M. M., Gallagher, J. J., & Schopler, E. (1988). Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and non-disabled boys: Adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology, 24, 442–445.

- Brummett, B. H., Babyak, M. A., Barefoot, J. C., Bosworth, H. B., Clapp-Channing, N. E., Siegler, I. C., Williams, R. B., Jr., & Mark, D. B. (1998). Social support and hostility as predictors of depressive symptoms in cardiac patients one month after hospitalization: A prospective study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(6), 707–713.

- Burkhauser, R. V., & Gertler, P. J. (Eds.). (1995). The health and retirement study. Data quality and early results [Special issue]. Journal of Human Resources, 30(Supplement).

- Buse, S., & Pieper, B. (1990). Impact of cardiac transplantation on the spouse’s life. Heart and Lung, 19, 641–648.

- Califf, R. M., Harrell, F. E., Jr., Lee, K. L., Rankin, J. S., Hlatky, A., Mark, D. B., Jones, R. H., Muhlbaier, L. H., & Oldham, H. N. (1989). The evolution of medical and surgical therapy for coronary artery disease: A 15-year perspective. Journal of the American Medical Association, 261, 2077–2086.

- Carney, R., Rich, M. W., teVelde, A., Saini, J., Clark, K., & Jaffe, A. S. (1987). Major depressive disorder in coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology, 60, 1273–1275.

- Carstensen, L. L. (2001). On the brink of a brand-new old age. New York Times, A19.

- Charlson, M., Szatrowski, T. P., Peterson, J., & Gold, J. (1994). Validation of a combined co-morbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 47, 1245–1251.

- Deeg, D. H. J., Kardaun, J. W. P. F., & Fozard, J. L. (1996). Health, behavior and aging. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (4th ed., pp. 129–149). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Deeg, D. H. J., van Zonneveld, R. J., van der Maas, P. J., & Habbema, J. D. (1989). Medical and social predictors of longevity in the elderly: total predictive value and interdependence. Social Science Medicine, 29(11), 1271–1280.

- Desai, M., Bruce, M. L., Desai, R. A., & Druss, B. G. (2001). Validity of self-reported cancer history: A comparison of health interview data and cancer registry records. American Journal of Epidemiology, 153(3), 299–306.

- DiMatteo, M. (1994). Enhancing patient adherence to medical recommendations. Journal of the American Medical Association, 271, 79–83.

- DiMatteo, M., & DiNicola, D. D. (1982). Achieving patient compliance. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

- DiMatteo, M., Lepper, H. S., & Croghan, T. W. (2000). Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(14), 2101– 2107.

- DiMatteo, M., Sherbourne, C. D., Hays, R. D., Ordway, L., Kravitz, R. L., McGlynn, E. A., Kaplan, S., & Rogers, W. H. I. (1993). Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychology, 12(2), 93–102.

- Eisdorfer, C., & Wilkie, F. W. (1977). Stress, disease, aging and behavior. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 251–275). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Elias, M. F., Elias, J. W., & Elias, P. K. (1990). Biological and health influences on behavior. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (3rd ed., pp. 79–102). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.