Sample Developmental Psychopathology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Developmental psychopathology can be defined in a variety of ways, all having to do with development on the one hand and the resulting set of maladaptive behaviors on the other. Developmental psychopathology focuses on and integrates these two areas, looking at maladaptive processes themselves as well. Underlying much of the study of developmental psychopathology is the principle of predictability. The prediction of maladaptive behavior has been viewed not only as possible, but also as an important feature in the study of psychopathology. With this added feature, we now have a more complete definition: Developmental psychopathology is the study and prediction of maladaptive behaviors and processes across time.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

As we can see, the definition of developmental psychopathology involves the merger of two fields of study, that of development and that of psychopathology. Although there is much interest in the etiology of psychopathology, until recently, there has been little research on the development of maladjustment. In part, this was due to the now discredited idea that some adult psychopathologies could not occur in childhood and to the misconception that the adult forms of pathology are the same as those for children. The introduction of a developmental perspective allows for the understanding that the same underlying psychopathology in children and in adults may be seen in very different behaviors. Thus, a developmental perspective is necessary in order to understand psychopathology.

1. Models Of Developmental Psychopathology

Three models, a trait model, a contextual or environmental model, and an interactional model reflect the various views in regard to development and, therefore, to the etiology of psychopathology. Because attachment theory remains central to normal and maladaptive development, it is used as an example in our discussion. Unfortunately, by describing sharp distinctions, we may draw too tight an image and, as such, may make them caricatures. Nevertheless, it is important to consider them in this fashion in order to observe their strengths and weaknesses and how they are related to developmental psychopathology.

1.1 Trait Or Status Model

The trait or status model is characterized by its simplicity, and holds to the view that a trait of the child at one point in time is likely to predict a trait at a later point in time. This model is not interactive and does not provide for the effects of the environment. In fact, in the most extreme form, the environment is thought to play no role either in effecting its display or in transforming its characteristics. A particular trait may interact with the environment, but the trait is not changed by that interaction.

Traits are not easily open to transformation and can be processes, coping skills, attributes, or tendencies to respond in certain ways. Traits can be innate features, such as temperament or particular genetic codes, or can be acquired through learning or through interactive processes with the environment. However, once a trait is acquired, it remains relatively unaffected by subsequent interactions. The trait model is most useful in many instances, for example, when considering potential genetic or biological causes of subsequent psychopathology. A child who is born with a certain gene or a set of genes is likely to display psychopathology at some later time. This model characterizes some of the research in the genetics of mental illness. Here, the environment, or its interaction with the genes, plays little role in the potential outcome. For example, the work on heritability of schizophrenia supports the use of such a model, as does the lack or presence of certain chemicals on depression.

In each of these cases, the trait model argues that presence of particular genes is likely to affect a particular type of psychopathology. Although a trait model is appealing in its simplicity, there are any number of problems with it; for example, not all people who possess a trait at one point in time are likely to show subsequent psychopathology or the same type of psychopathology. That all children of schizophrenic parents do not themselves become schizophrenic, or that not all monozygotic twins show concordance vis-a-vis schizophrenia, suggests that other variables need to be considered.

This model also is useful when considering traits that are not genetically or biologically based, but based on very early experiences. For example, the attachment model as proposed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth holds that the child’s early relationship with its mother, in the first year of life, creates a trait (secure or insecure attachment) which will determine the child’s adjustment throughout his or her life. The security of attachment that the child shows at the end of the first year of life is the result of the early interaction between the mother and the child. Once the attachment is established, it acts as a trait affecting the child’s subsequent behavior.

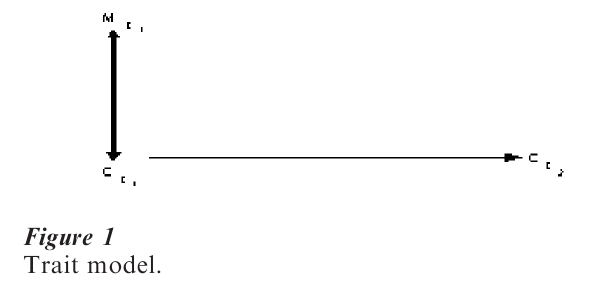

Figure 1 presents the trait model. Notice that the interaction of the mother and child at T1 produces the trait, Ct1 ; in the attachment case, a secure or an insecure child. Although attachment is the consequence of an interaction, once established, it is the trait (Ct1) residing in the child that leads to Ct . There is no need to posit a role of the environment except as it initially produces the attachment.

The trait model is widely used in the study of developmental psychopathology; for example, the concept of the vulnerable or invulnerable child. A vulnerable child is defined as one who has some characteristic (trait), acquired early, which makes them vulnerable, even if they show no ongoing problems. Once stress appears, this trait is expressed. As Alan Sroufe has said, ‘even when the child changes rather markedly, the shadows underlying that of the earlier adaptation remains [the insecure attachment] and in times of stress, the prototype itself may be clear (Sroufe 1983, p. 74).

On the other hand, the invulnerable child, even when stressed, is less likely to show pathology. Such a model of invulnerability has been used by Norman Garmezy and Michael Rutter (1983) to explain why children raised in highly stressful environments do not all show psychopathology. In the attachment literature, a secure child is more likely to be invulnerable to subsequent stress, whereas an insecure child is more vulnerable to stress.

The trait notion leaves little room for the impact of environment on subsequent developmental growth or dysfunction. Environments play a role in children’s development in the opening year of life and continue to do so throughout the life span.

1.2 The Environmental Model

The prototypic environmental model holds that exogenous factors influence development. Two of the many problems in using this model are our difficulty in defining what environments are, and the failure to consider the impact of environments throughout the life span. In fact, the strongest form of the environmental or contextual model argues for the proposition that adaptation to current environment, throughout the life course, is a major influence in our socio-emotional life. As environments change, so too does the individual. This dynamic and changing view of environments and adaptation is in strong contrast to the earlier models of environments as forces acting on the individual, and acting on the individual only in the early years of life.

In the simplest model, behavior is primarily a function of the environmental forces acting on the organism at any point in time. In such a model, a child does behavior x but not behavior y, because behavior x is positively rewarded by his or her parents and y is punished. Notice that, in this model, environmental forces act continuously on the organism, and the behavior emitted is a direct function of this action. Much of our behavior is controlled by an indirect form of environmental pressure. For example, a young child is present when the mother scolds the older sibling for writing on the walls. The younger child, although not directly punished, learns that writing on walls will be punished. Indirect forms of reward and punishment have received little attention, but exert as much environmental influences as direct forms.

There are many other types of environmental pressures. For example, we see an advertisement for a product ‘that will make other people love us.’ We purchase such a product in the hopes that others will indeed love us. We can reward or punish ourselves by our knowledge of what is correct or incorrect according to the environmental standards that we learn. Poor environmental effects, such as an overdeveloped sense of standards, can lead to high shame and, through it, to other forms of psychopathology.

Because other people make up one important aspect of our environment, the work on the structures of the social environment is particularly relevant, and an attempt has been made to expand the numbers of potentially important people in the child’s environment beyond the mother. Sociologists and some psychologists, such as Urie Bronfenbrenner, Michael Lewis, and Judy Dunn have argued that other persons, including fathers, siblings, grandparents, and peers, clearly have importance in shaping the child’s life. Given these diverse features of environments and the important roles attributed to them, it is surprising that so little systematic work has gone into their study. For the most part, mothers and, to some extent, families, have received the most attention and we, therefore, use them in our examples.

The role of environments in the developmental process has been underplayed because most investigators seek to find the structure and change within the organism itself. Likewise, in the study of psychopathology, even though we recognize that environments can cause disturbance and abnormal behavior, we prefer to treat the person—to increase coping skills or to alter specific behaviors—rather than change the environment. Yet we can imagine the difficulties that are raised when we attempt to alter specific maladaptive behaviors in environments in which such behaviors are adaptive—a point well taken by Thomas Szasz.

Our belief that the thrust of development resides in the organism rather than in the environment, in large part, raises many problems. At cultural levels, we assume that violence (and its cure) must be met in the individual—a trait model—rather than in the structure of the environment. The murder rate using handguns in the USA is many times higher than in any other Western society. We seek responsibility in the nature of the individual (e.g., XYY males, or the genetics of antisocial behavior), when the alternative of environ- mental structure is available. In this case, murders may be due more to the culture’s nonpunishment of persons or nonrestriction of handguns. The solution to the high murder rate in the USA might be the elimination, through punishment, of the possession of weapons. Thus, we either conclude that Americans are by nature more violent than Europeans or that other Western societies do not allow handguns and therefore have lower murder rates.

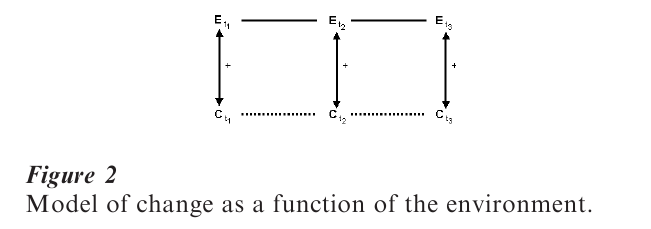

Figure 2 presents the general environmental model. The environment (E) at t1, t2, and t3 all impact on the child’s behavior at each point in time. The child’s behavior at Ct1, Ct2, and Ct3 appears consistent, and it is, as long as E remains consistent. In other words, the continuity in C is an epiphenomenon of the continuity of E across time. Likewise, the lack of consistency in C reflects the lack of consistency in the environment. The child’s behavior changes over t1 to t2 as the environment produces change. Even though it appears that C is consistent, it is so because E is consistent. Consistency and change in C are supported by exogenous rather than by endogenous factors.

Other forms of maladaptive behavioral development have a similar problem. Depressed women are assumed to cause concurrent as well as subsequent depression in children. What is not considered is the fact that depressed mothers at t are also likely to be depressed at t2 or t3. What role does the mother’s depression at these points play in the child’s subsequent condition? We can only infer the answer given the limited data available. The question that needs to be asked is: What would happen to the child if the mother was depressed at t1 but not at t2 or t3? This type of question suggests that one way to observe the effect of the environment on the child’s subsequent behavior is to observe those situations in which the environment changes.

The environmental model is characterized by the view that the constraints, changes, and consistencies in children’s psychopathology rest not so much with intrinsic structures located in the child as in the nature, structure, and environment of the child.

1.3 The Interactional Or Transformational Model

Interactional models vary; Michael Lewis (1990) prefers to call them ‘interactional’, while Sameroff (1975) calls them ‘transactional.’ All these models have in common the role of both child and environment in determining the course of development. In these models, the nature of the environment and the traits of the child are needed to explain concurrent as well as subsequent behavior and adjustment. Maladaptive behavior may be misnamed because the behavior may be adaptive to a maladaptive environment. The stability and change in the child need to be viewed as a function of both factors and, as such, the task of any interactive model is to draw us to the study of both features. In our attachment example, the infant who is securely attached, as a function of the responsive environment in the first year, will show competence at a later age as a function of the earlier events as well as the nature of the environment at that later age.

One of the central issues of the developmental theories that are interactive in nature is the question of transformation. Two models of concurrent behavior as a function of traits and environment can be drawn. In the first, both trait and environment interact and produce a new set of behaviors. However, neither the traits nor the environment are altered by the interaction. From a developmental perspective, this is an additive model because new behaviors are derived from old behaviors and their interaction with the environment, but these new behaviors are added to the repertoire of the set of old behaviors. This model is very useful for explaining such diverse psychopathological phenomena as regression and vulnerability. In its most general form, it has been called by Richard Lerner (1986), the goodness-of-fit model.

In the second model, both trait and environment interact, producing a new set of behaviors which transform themselves. From a developmental perspective, this is a transformational model because the old behaviors give rise to new behaviors and the environment itself is altered by the exchange. The variety of interactional or transactional models is considerable.

2. Future Directions

The understanding of these different models of development directly bear on the type of research on developmental psychopathology. It seems reasonable to assume that different forms of psychopathology have different developmental pathways, some fitting one or the other of these models. The task for the future is to articulate which forms of psychopathology are best explained by what models.

Bibliography:

- Ainsworth M D 1973 The development of infant–mother attachment. In: Caldwell B M, Ricciuti H N (eds.) Review of Child Development Research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Vol. 3, pp. 1–95

- Bowlby J 1969 Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1, Attachment. Basic Books, New York

- Bronfenbrenner U 1979 The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Dunn J 1993 Young Children’s Close Relationships. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Garmezy N, Rutter M 1983 Stress, Coping, and Development in Children. McGraw Hill, New York

- Lerner R M 1986 Concepts and Theories of Human Development, 2nd edn. Random House, New York

- Lewis M 1987 Social development in infancy and early childhood. In: Osofsky J D (ed.) Handbook of Infant Development, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York, pp. 419–93

- Lewis M 1990 Models of developmental psychopathology. In: Lewis M, Miller S M (eds.) Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 15–28

- Lewis M 1997 Altering Fate: Why the Past does not Predict the Future. Guilford Press, New York

- Sameroff A 1975 Transactional models in early social relations. Human Development 18: 65–79

- Sroufe L A 1983 Infant–caregiver attachment and patterns of adaptation in preschool: The roots of maladaptation and competence. Minnesota Symposia in Child Psychology 16: 41–83

- Szasz T S 1961 The Myth of Mental Illness. Hoeber-Harper, New York