View sample cognitive development in adolescence research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In this research paper, we focus on two major aspects of adolescent development: cognitive development and both achievement and achievement motivation. First we discuss cognitive development, pointing out the relevance of recent work for both learning and decision making. Most of the paper focuses on achievement and achievement motivation. We summarize current patterns of school achievement and recent changes in both school completion and differential performance on standardized tests of achievement. Then we summarize both the positive and negative age-related changes in school motivation and discuss how experiences in school might explain these developmental patterns. Finally, we discuss both gender and ethnic group differences in achievement motivation and link these differences to gender and ethnic group differences in academic achievement and longer-term career aspirations.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Cognitive Development in Adolescence

In this section, we review work related to cognitive development. At a general level, the most important cognitive changes during this period of life relate to the increasing ability of youth to think abstractly, consider the hypothetical as well as the real, engage in more sophisticated and elaborate information-processing strategies, consider multiple dimensions of a problem at once, and reflect on oneself and on complicated problems (see Keating, 1990). Indeed, such abstract and hypothetical thinking is the hallmark of Piaget’s formal operations stage assumed to begin during adolescence and to continue through young adulthood (e.g., Piaget & Inhelder, 1973). Although there is still considerable debate about when exactly these kinds of cognitive processes emerge and whether their emergence reflects global stagelike changes in cognitive skills as described by Piaget, most theorists do agree that these kinds of thought processes are more characteristic of youth’s cognition than of younger children’s cognition.

At a more specific level, along with their implications for learning and problem solving, these kinds of cognitive changes affect individuals’ self-concepts, thoughts about their future, and understanding of others. Theorists from Erikson (1968) to Harter (1990), Eccles (Eccles & Barber, 1999), and Youniss (Youniss, McLellan, & Yates, 1997) have suggested that the adolescent and emerging adulthood years are a time of change in youth’s self-concepts, as they consider what possibilities are available to them and try to come to a deeper understanding of themselves. These sorts of selfreflections require the kinds of higher-order cognitive processes just discussed.

Finally, during adolescence individuals also become more interested in understanding others’ internal psychological characteristics, and friendships become based more on perceived similarity in these characteristics (see Selman, 1980). Again, these sorts of changes in person perception reflect the broader changes in cognition that occur during adolescence. We turn now to a more detailed discussion of cognitive development during the adolescent years.

Are there age changes in the structural and functional aspects of cognition, and do these age-related trajectories in cognitive skills differ across gender and ethnic groups? In this section we summarize the research relevant to these questions. A fuller treatment can be found in sources such as Byrnes (2001a, 2001b) and Bjorklund (1999).

Age Changes in Structural and Functional Aspects

Changes in Structural Aspects

Structural aspects of cognition include the knowledge possessed by an individual as well as the information-processing capacity of that individual. Structuralist researchers often focus on the following two questions: (a) What changes occur in children’s knowledge as they progress through the adolescent period? and (b) What changes occur in the information-processing capacities of adolescents?

Knowledge Changes. The term knowledge refers to three kinds of information structures that are stored in long term memory: declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, and conceptual knowledge (Byrnes, 2001a, 2001b). Declarative knowledge or “knowing that” is a compilation of all of the facts an adolescent knows (e.g., knowing that 2 + 2 = 4; knowing that Harrisburg is the capital of Pennsylvania). Procedural knowledge or “knowing how to” is a compilation of all of the skills an adolescent knows (e.g., knowing how to add numbers; knowing how to drive a car). The third kind of knowledge, conceptual knowledge, is the representation of adolescents’understanding of their declarative and procedural knowledge. Conceptual knowledge is “knowing why” (e.g., knowing why one should use the least common denominator method to add fractions).

Various sources in the literature suggest that these forms of knowledge increase with age (Byrnes, 2001). The clearest evidence of such changes can be found in the National Assessments of Educational Progress (NAEPs) conducted by the U.S. Department of Education every few years. The NAEP tests measure the declarative, procedural, and conceptual knowledge of fourth, eighth, and 12th graders (N’s > 17,000) in seven domains: reading, writing, math, science, history, geography, and civics. In math, for example, NAEP results show that children progress from knowing arithmetic facts and being able to solve simple word problems in Grade 4 to being able to perform algebraic manipulations, create tables, and reason about geometric shapes by Grade 12 (Reese, Miller, Mazzeo, & Dossey, 1997). Although similar gains are evident for each of the domains (Beatty, Reese, Perksy, & Carr, 1996), in no case can it be said that a majority of 12th graders demonstrate a deep conceptual understanding in any of the domains assessed (Byrnes, 2001a, 2001b). One reason for the low level of conceptual knowledge in 12th graders is the abstract, multidimensional, and counterintuitive nature of the most advanced questions in each domain. Even in the best of circumstances, concepts such as scarcity, civil rights, diffusion, limit, and conservation of energy are difficult to grasp and illustrate. Moreover, the scientific definitions of such concepts are often counter to students’ preexisting ideas. As a result, there are numerous studies showing misconceptions and faulty information possessed by adolescents and adults (see Byrnes 2001a, 2001b).

In sum, then, one can summarize the results on knowledge as follows:

- In most school-related subject areas, there are modest, monotonic increases in declarative, procedural, and conceptual knowledge between the fourth grade and college years.

- Misconceptions abound in most school subjects and are evident even in 12th graders and college students.

- The most appropriate answer to the question “Does knowledge increase during adolescence?” is the following: It depends on the domain (e.g., math vs. interpersonal relationships) and type of knowledge (e.g., declarative vs. conceptual).

- Although there is little evidence of dramatic and acrossdomain increases in understanding, there is consistent evidence of incremental increases in within-domain understanding as children move into and through adolescence.

Do these kinds of changes in knowledge influence behavior? For example, do older adolescents make better life decisions because they know more? Are they better employees? Parents? College students? Lifelong learners? At some level, the answer to these questions has to be yes. Certainly expanded domain-specific knowledge makes it easier to solve problems and perform complex tasks in activities very closely linked to the same knowledge domain (Byrnes, 2001a, 2001b; Ericcson, 1996). But does expanded knowledge on its own increase the wisdom of more general life decisions? The answer to this question is less clear because such decisions depend on many other aspects of cognitive as well as motivational and emotional processes that influence the likelihood of accessing and effectively using one’s stored knowledge. For example, younger adolescents may have the knowledge needed to make decisions or solve problems (on achievement tests or in social situations) but may lack the processing space needed to consider and combine multiple pieces of information. We turn to these other aspects of cognition now.

Capacity Changes. Are there age-related increases in cognitive processing capacity? Processing space is analogous to random-access memory (RAM) on a computer. A very good software package may not be able to work properly if the RAM on a PC is too small. One key index of processing capacity in humans is working memory—the ability to temporarily hold something in memory (e.g., a phone number). It used to be assumed that working memory capacity changes very little after childhood. In fact, however, until quite recently this assumption had not been adequately tested. Several recent studies suggest that working memory does increase during adolescence. For example, Zald and Iacono (1998) charted the development of spatial working memory in 14- and 20-year-olds by assessing their memory for the location of objects that were no longer visible. They found that the introduction of delays and various forms of cognitive interference produced drops in performance that were sharper in the younger than in the older participants. Similarly, Swanson (1999) found monotonic increases in both verbal and spatial working memory between the ages of 6 and 35 in a large normative sample. Such increases should make it easier for older adolescents and adults to consider multiple pieces of information simultaneously in making important decisions. This hypothesis needs more extensive study.

Changes in Functional Aspects of Cognition

Functionalist aspects of cognition include any mental processes that alter, operate on, or extend incoming or existing information. Examples include learning (getting new information into memory), retrieval (getting information out of memory), reasoning (drawing inferences from single or multiple items of information), and decision making (generating, evaluating, and selecting courses of action). As noted earlier, both structural and functional aspects of cognition are critical to all aspects of learning, decision-making, and cognitive activities. For example, experts in a particular domain learn new, domain-relevant items of information better than novices do. Also, people are more likely to make appropriate inferences and make good decisions when they have relevant knowledge than when they do not have relevant knowledge (Byrnes, 1998; Ericsson, 1996). With this connection in mind, we can consider the findings sampled from several areas of research (i.e., deductive reasoning, decision making, other forms of reasoning) to get a sense of age changes in functional aspects.

Deductive Reasoning. People engage in deductive reasoning whenever they combine premises and derive a logically sound conclusion from these premises (S. L. Ward & Overton, 1990). For example, given the premises (a) Either the butler or the maid killed the duke and (b) The butler could not have killed the duke, one can conclude The maid must have killed the duke. Adolescents are likely to engage in deductive reasoning as they try to make sense of what is going on in a context and what they are allowed to do in that context. Moreover, deductive reasoning is used when they write argumentative essays, test hypotheses, set up algebra and geometry proofs, and engage in debates and other intellectual discussions. It is also critical to decision making and problem solving of all kinds.

Although the issue of age differences in deduction skills is somewhat controversial, most researchers believe that there are identifiable developmental increases in deductive reasoning skills between childhood and early adulthood. Competence is first manifested around age 5 or 6 in the ability to draw some types of conclusions from “if-then” (conditional) premises, especially when these premises refer to fantasy or make-believe content (e.g., Dias & Harris, 1988). Several years later, children begin to understand the difference between conclusions that follow from conditional premises and conclusions that do not (Byrnes & Overton, 1986; Girotto, Gilly, Blaye, & Light, 1989; Haars & Mason, 1986; Janveau-Brennan & Markovits, 1999), especially when the premises refer to familiar content about taxonomic or causal relations. Next, there are monotonic increases during adolescence in the ability to draw appropriate conclusions, explain one’s reasoning, and test hypotheses, even when premises refer to unfamiliar, abstract, or contrary-tofact propositions (Klaczynski, 1993; Markovits & Vachon, 1990; Moshman & Franks, 1986; S. L. Ward & Overton, 1990). Again, however, performance is maximized on familiar content about legal or causal relations (Klaczynski & Narasimham, 1998). However, when the experimental content runs contrary to what is true (e.g., All elephants are small animals. This is an elephant. Is it small?) or has no meaningful referent (e.g., If there is a D on one side of a card, there is a 7 on the other), less than half of older adolescents or adults do well.

Performance on the latter tasks can, however, be improved in older participants if the abstract problems are presented after exposure to similar but more meaningful problems or if the logic of the task is adequately explained (Klaczynski, 1993; Markovits & Vachon, 1990; S. L. Ward, Byrnes, & Overton, 1990). Even so, such interventions generally have only a weak effect. These findings imply that most of the development after age 10 in deductive reasoning competence is in the ability to suspend one’s own beliefs and think objectively about the structure of an argument (e.g., “Let’s assume for the moment that this implausible argument is true . . .”; Moshman, 1998). Little evidence exists for an abstract, domain-general ability that is spontaneously applied to new and different content.

Decision Making. When people make decisions, they set a goal (e.g., get something to eat), compile options for attaining that goal (e.g., go out, find something in the refrigerator, etc.), evaluate these options (e.g., eating at home is cheaper and healthier than eating out), and finally implement the best option. Alternatively, they must decide whether to engage in a particular behavior that is made available to them in a specific situation (e.g., they decide whether to have sexual intercourse in an intimate encounter or to accept an offered alcoholic drink or illicit drug). Competent decision making entails the ability to identify the risks and benefits of particular behaviors as well as the ability to identify options likely to lead to positive, health-promoting outcomes (e.g., stable relationships, good jobs, physical health, emotional health, etc.) or promote one’s short- and long-term goals. Clearly, good decision-making skills are among the most important cognitive skills adolescents need to acquire.

Given the centrality of decision making, it is surprising that so few developmental studies have been conducted (Byrnes, 1998; Klaczynski, Byrnes, & Jacobs, 2001). Considered together, the widely scattered (and sometimes unreplicated) findings suggest that older adolescents and adults seem to be more likely than are younger adolescents or children to (a) understand the difference between options likely to satisfy multiple goals and options likely to satisfy only a single goal (Byrnes & McClenny, 1994; Byrnes, Miller, & Reynolds, 1999), (b) anticipate a wider range of consequences of their actions (Lewis, 1981; Halpern-Felsher & Cauffman, 2001), and (c) learn from their decision-making successes and failures with age (Byrnes & McClenny, 1994; Byrnes, Miller, & Reynolds, 1999). There is also some suggestion that adolescents are more likely to make good decisions when they have metacognitive insight into the factors that affect the quality of decision making (D. C. Miller & Byrnes, 2001; Ormond, Luszcz, Mann, & Beswick, 1991). However, most of the studies that support these conclusions involved laboratory tasks, hypothetical scenarios, or self-reports. In real-world contexts, other emotional and motivational factors are likely to seriously affect the quality of adolescents’ decisions. For example,adolescentsmaythinktheywillfindaparticularoutcome enjoyable, only to learn later that it was not, either because they had inadequate self-knowledge or because they failed to use the self-knowledge that they had. High states of emotional arousal or intoxication can also reduce an adolescent’s ability and motivation to generate, evaluate, and implement success-producing options and to adequately assess the risks associated with various behavioral options. Hence, adolescents and adults who look good in the lab may nevertheless make poor decisions in the real world if they lack appropriate self-regulatory strategies for dealing with such possibilities (e.g., self-calming techniques, coping with peer pressure to drink, etc.). Additional studies are clearly needed to examine such issues. The recent work by Baltes and his colleagues on the selection-optimization-compensation (SOC) models of adaptive behavior provides one useful approach for such research (see Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 1998).

In contrast to the dearth of studies on decision making in adolescents, there are quite a number of developmental studies in a related area of research: risk taking (Byrnes, 1998). If a decision involves options that could lead to negative or harmful consequences (i.e., anything ranging from mild embarrassment to serious injury or death), adolescents who pursue such options are said to have engaged in risk-taking (Byrnes, Miller, & Schaefer, 1999). Although all kinds of risk taking are of interest from scientific standpoint, most studies have focused on age changes in physically harmful behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and unprotected sex. Regrettably, these studies reveal the opposite of what one would expect if decision-making skills improve during adolescence; instead, these studies show that older adolescents are more likely than younger adolescents or preadolescents to engage in these behaviors (DiClemente, Hansen, & Ponton, 1995). Repeatedly, studies have shown that those who take such risks do not differ in their knowledge of possible negative consequences. Given that risk-takers and risk-avoiders do not differ in their knowledge of options and consequences, it is likely that the difference lies in other aspects of competent decision making (e.g., self-regulatory strategies, ability to coordinate health-promoting and social goals, etc.). This hypothesis remains to be tested.

Other Functional Aspects. In addition to finding agerelated increases in deductive reasoning and decision-making skills, researchers have also found increases in mathematical reasoning ability, certain kinds of memory-related processes, the ability to perform spatial reasoning tasks quickly, and certain aspects of scientific reasoning (Byrnes, 2001a). The variables that seem to affect the size of these increases include (a) whether students have to learn information during the experiment or retrieve something known already, and (b) the length of the delay between stimulus presentation and being asked to retrieve information. In the case of scientific reasoning, the ability to consciously construct one’s own hypotheses across a wide range of contents, test these hypotheses in controlled experiments, and draw appropriate inferences also increases (Byrnes, 2001a, 2001b; Klaczynski & Narasimham, 1998; Kuhn, Garcia-Mila, Zohar, & Andersen, 1995).

Summary

The literature suggests that there are changes in the intellectual competencies of youth as they progress through the adolescent period. However, there are many ways in which the thinking of young adolescents is similar to that of older adolescents and adults. Thus, before one can predict whether an age difference will manifest itself on any particular measure of intellectual competence, one needs to ask questions such as “Does exposure to the content of the task continue through adolescence?”, “Do many issues have to be held in mind and considered simultaneously?, “Are the ideas consistent with naive conceptions?”, and “Does success on the task require one to suspend one’s beliefs?” If the answers to these questions are all “no,” then younger adolescents, older adolescents, and adults should perform about the same. However, if one or more “yes” answer is given, then one would expect older adolescents and adults to demonstrate more intellectual competence than younger adolescents.

Gender and Ethnic Differences in Cognition

It is not possible to provide a comprehensive summary of the vast literature on gender and ethnic differences in a single research paper or portion of a paper. One can, however, provide an overview of some of the essential findings (see Byrnes, 2001a, 2001b, for a more complete summary). With respect to gender differences, male and female adolescents perform comparably on measures of math, science, and social studies knowledge (e.g., NAEPs) and also obtain nearly identical scores on measures of intelligence, deductive reasoning, decision making, and working memory. Two areas in which gender differences have appeared are risk taking and Scholastic Achievement Test (SAT) math performance. With regard to risk taking, the pattern is quite mixed: Males are more likely than females to take such risks as driving recklessly or taking intellectual risks; in contrast, females are more likely than males to take such health risks as smoking. The size of such gender differences, however, varies by age (Byrnes, Miller, & Schaefer, 1999). These findings seem to reflect differences in males’ and females’ expectations, values, and self-regulatory tendencies.

With regard to gender differences on SAT-math scores, male’s scores are routinely slightly higher than are female’s scores (De Lisi & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, 2002). It is still not clear why this difference obtains, given the fact that there are no gender differences in math knowledge or gender differences in other kinds of reasoning. Researchers have shown, however, that part of this difference reflects gender differences in test-taking strategies, confidence in one’s math ability, ability and motivation to use unconventional problem-solving strategies, mental rotation skills, and anxiety about one’s math ability, particularly when one’s gender is made salient (see De Lisi & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, 2002, for review).

With respect to ethnic differences, European American and Asian American students perform substantially better than do African American, Hispanic and Native American students on standardized achievement tests, the SAT, and most of the NAEP tests. In contrast, no ethnic differences are found in studies of deductive reasoning, decision-making, or working memory. Moreover, ethnic differences on tests such as the SAT and NAEP are substantially reduced after variables such as parent education and prior course work are controlled (Byrnes, 2001). We know even less about the origins of these ethnic group differences than we know about the origins of gender differences in cognitive performance.

Achievement and Achievement-Related Beliefs

The picture of achievement for adolescents in the United States is mixed. More youth than ever are graduating from high school, and a large number are enrolled in some form of higher education (National Center for Educational Statistics, 1999; Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1988). High school dropout rates, although still unacceptably large in some population subgroups, are at all-time lows (National Center for Educational Statistics, 1999; Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1988). Comparable improvements in educational attainment over the last century characterize all Western industrialized countries as well as many developing countries.

In contrast to these quite positive trends in academic achievement, a substantial minority of America’s adolescents are not doing very well in terms of academic achievement and school-related achievement motivation: First and foremost, America’s adolescents on average perform much worse on academic achievement tests than do adolescents from many other countries (National Center for Educational Statistics, 1995). Between 15 and 30% of America’s adolescents drop out of school before completing high school; and many others are disenchanted with school and education (Kazdin, 1993; Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1988). Both the rates of dropping out and disengagement are particularly marked among poor youth and both Hispanic and Native American youth.

There are also mean level declines in such motivational constructs as grades (Simmons & Blyth, 1987), interest in school (Epstein & McPartland, 1976), intrinsic motivation (Harter, 1981), and self-concepts (Eccles et al., 1989; Wigfield, Eccles, Mac Iver, & Reuman, 1991; Simmons & Blyth, 1987) in conjunction with the junior high school transition. For example, Simmons and Blyth (1987) found a marked decline in some young adolescents’ school grades as they moved into junior high school—the magnitude of which predicted subsequent school failure and dropout (see also Roderick, 1993). Several investigators have also found drops in self-esteem as adolescents make the junior and senior high school transitions—particularly (but not always only) among European American girls (Eccles et al., 1989; Simmons & Blyth, 1987; Wigfield et al., 1991). Finally, there is evidence of similarly timed increases in such negative motivational and behavioral characteristics as focus on self-evaluation rather than task mastery (e.g., Maehr & Anderman, 1993), test anxiety (Hill & Sarason, 1966), and both truancy and school dropout (Rosenbaum, 1976; see Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiefele, 1998, for full review).

Few studies have gathered information on ethnic and social class differences in these declines. However, academic failure and dropout are especially problematic among African American and Hispanic youth and among youth from lowSES (socioeconomic status) communities and families (Finn, 1989). It is probable then that these groups are particularly likely to show these declines in academic motivation and self-perceptions as they move into and through the years of secondary school. We discuss this possibility more later in this research paper.

Although these changes are not extreme for most adolescents, there is sufficient evidence of gradual declines in various indicators to make one wonder what is happening (see Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Avariety of explanations have been offered. Some scholars attribute these declines to the intrapsychic upheaval assumed to be associated with early pubertal development (see Arnett, 1999). Others have suggested that they result from the coincidence of multiple life changes. For example, drawing upon cumulative stress theory, Simmons and her colleagues suggest that declines in motivation result from the fact that adolescents making the transition to junior high school at the end of Grade 6 must cope with two major transitions: pubertal change and school change (see Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Because coping with multiple transitions is more difficult than coping with only one, these adolescents are at greater risk of negative outcomes than are adolescents who have to cope with only pubertal change during this developmental period. To test this hypothesis, Simmons and her colleagues compared the pattern of changes on the school-related outcomes of young adolescents who moved from sixth to seventh grade in a K–8, 9–12 system with the pattern of changes for those who made the same grade transition in a K–6, 7–9, 10–12 school system. They found clear evidence, especially among girls, of greater negative changes for those adolescents making the junior high school transition than for those remaining in the same school setting (i.e., those in K–8, 9–12 schools). The fact that the junior high school transition effects were especially marked for girls was interpreted as providing additional support for the cumulative stress theory, because at this age girls are more likely than boys are to be undergoing both a school transition and pubertal change. Further evidence in support of the role of the cumulative stress came from Simmons and Blyth’s (1987) analyses comparing adolescents who experienced varying numbers of other life changes in conjunction with the junior high school transition. The negative consequences of the junior high school transition increased in direct proportion to the number of other life changes an adolescent also experienced as he or she made the school transition.

The Junior High School Transition

Eccles and her colleagues have focused on the school transition itself as a possible cause of academic-motivational declines.Asnotedpreviously,manyofthesedeclinescoincide with school transitions. The strongest such evidence comes from work focused on the junior high school transition—for example, the work just discussed by Simmons and Blyth. Eccles and her colleagues have obtained similar results using the data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study. They compared eighth graders in K–8 school systems with eighth graders in either K–6, 7–9 systems or K–5, 6–8 systems. The eighth-grade students in the K–8 systems looked better on such motivational indicators as self-esteem, preparedness, and attendance than did the students in either of the other two types of school systems (Eccles, Lord, & Buchanan, 1996).Inaddition,theeighth-gradeteachersintheK–8system reported fewer student problems, less truancy, and more student engagement than did the teachers in either of the other two types of school systems. Clearly, both the young adolescents and their teachers fared better in K–8 school systems than did those in the more prevalent junior high school and middle school systems. Why?

Several investigators have suggested that the changing nature of the educational environments experienced by many young adolescents helps explain these types of school system differences as well as the mean level declines in the schoolrelated measures associated with the junior high school transition (e.g., Eccles, Midgley, Buchanan, Wigfield, Reuman & Mac Iver, 1993; Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Lipsitz, 1984; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Drawing upon personenvironment fit theory (see Hunt, 1979), Eccles and Midgley (1989) proposed that these motivational and behavioral declines could result from the fact that junior high schools are not providing appropriate educational environments for many young adolescents. According to person-environment theory, behavior, motivation, and mental health are influenced by the fit between the characteristics individuals bring to their social environments and the characteristics of these social environments (Hunt, 1979). Individuals are not likely to do very well or be very motivated if they are in social environments that do not fit their psychological needs. If the social environments in the typical junior high school do not fit very well with the psychological needs of adolescents, then person-environment fit theory predicts a decline in adolescents’motivation, interest, performance, and behavior as they move into this environment. Furthermore, Eccles and Midgley (1989) argued that this effect should be even more marked if the young adolescents experience a fundamental change in their school environments when they move into a junior high school or middle school—that is, if the school environment of the junior high school or middle school fits less well with their psychological needs than did the school environment of the elementary school.

This analysis suggests several questions. First, what are the developmental needs of the early adolescent? Second, what kinds of educational environment are developmentally appropriate for meeting these needs and stimulating further development? Third, what are the most common school environmental changes before and after the transition to middle or junior high school? Fourth—and most important—are these changes compatible with the physiological, cognitive, and psychological changes early adolescents are experiencing? Or is there a developmental mismatch between maturing early adolescents and the classroom environments they experience before and after the transition to middle or junior high school that results in a deterioration in academic motivation and performance for some children?

Eccles and Midgley (1989) argued that there are developmentally inappropriate changes at the junior high or middle school in a cluster of classroom organizational, instructional, and climate variables, including task structure, task complexity, grouping practices, evaluation techniques, motivational strategies, locus of responsibility for learning, and quality of teacher-student and student-student relationships. They hypothesized that these changes contribute to the negative change in early adolescents’ motivation and achievementrelated beliefs.

Is there any evidence that such a negative change in the school environment occurs with the transition to junior high school? Most relevant descriptions have focused on schoollevel characteristics such as school size, degree of departmentalization, and extent of bureaucratization. For example, Simmons and Blyth (1987) point out that most junior high schools are substantially larger (by several orders of magnitude) than elementary schools, and instruction is more likely to be organized departmentally. As a result, junior high school teachers typically teach several different groups of students, making it very difficult for students to form a close relationship with any school-affiliated adult at precisely the point in development when there is a great need for guidance and support from nonfamilial adults. Such changes in student-teacher relationships are also likely to undermine the sense of community and trust between students and teachers, leading to a lowered sense of efficacy among the teachers, an increased reliance on authoritarian control practices by the teachers, and an increased sense of alienation among the students. Finally, such changes are likely to decrease the probability that any particular student’s’difficulties will be noticed early enough to get the student the help he or she needs, thus increasing the likelihood that students on the edge will be allowed to slip onto negative motivational and performance trajectories leading to increased school failure and dropout. Recent work by Elder and his colleagues (Elder & Conger, 2000) and classic work on the disadvantages of large schools by Barker and Gump (1964) provide strong support for these suggestions.

These structural changes are also likely to affect classroom dynamics, teacher beliefs and practices, and student alienation and motivation in the ways proposed by Eccles and Midgley (1989). Some support for these predictions is emerging, along with evidence of other motivationally relevant systematic changes (e.g., Maehr & Midgley, 1996; B. A. Ward et al., 1982).

First, despite the increasing maturity of students, junior high school classrooms—as compared to elementary school classrooms—are characterized by a greater emphasis on teacher control and discipline and fewer opportunities for student decision making, choice, and self-management (e.g., Midgley & Feldlaufer, 1987; Moos, 1979). For example, junior high school teachers spend more time maintaining order and less time actually teaching than do elementary school teachers (Brophy & Evertson, 1976).

Similar differences emerge on indicators of student opportunity to participate in decision making regarding their own learning. For example, Midgley and Feldlaufer (1987) reported that both seventh graders and their teachers in the first year of junior high school indicated less opportunity for students to participate in classroom decision making than did these same students and their sixth-grade elementary school teachers 1 year earlier.

Such declines in the opportunity for participation in decision making and self-control are likely to be particularly detrimental at early adolescence. This is a time in development when youth begin to think of themselves as young adults. It is also a time when they increase their exploration of possible identities. They believe they are becoming more responsible and consequently deserving of greater adult respect. Presumably, the adults responsible for their socialization would also like to encourage them to become more responsible for themselves as they move towards adulthood; in fact, this is what typically happens across the elementary school grades (see Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Unfortunately, the evidence suggests this developmentally appropriate progression is disrupted with the transition to junior high school.

In their stage-environment fit theory, Eccles and Midgley (1989) hypothesize that the mismatch between young adolescents’desires for autonomy and control and their perceptions of the opportunities in their learning environments will result in a decline in the adolescents’intrinsic motivation and interest in school. Mac Iver and Reuman (1988) provided some support for this prediction. They compared the changes in intrinsic interest in mathematics for adolescents reporting different patterns of change in their opportunities for participation in classroom decision-making items across the junior high school transition. Those adolescents who perceived their seventh-grade math classrooms as providing fewer opportunities for decision making that had been available in their sixth-grade math classrooms reported the largest declines in their intrinsic interest in math as they moved from the sixth grade into the seventh grade.

Second, junior high school classrooms (as compared to elementary school classrooms) are characterized by less personal and positive teacher-student relationships (Feldlaufer, Midgley, & Eccles, 1988). Furthermore, the transition into a less supportive classroom impacts negatively on early adolescents’ interest in the subject matter being taught in that classroom, particularly among low-achieving students (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989b).

Such a shift in the quality of student-teacher relationships is likely to be especially detrimental at early adolescence. As adolescents explore their own identities, they are prone to question the values and expectations of their parents. In more stable social groups, young adolescents often have the opportunity to do this questioning with supportive nonparental adults such as religious counselors, neighbors, and relatives. In our highly mobile, culturally diverse society, such opportunities are not as readily available. Teachers are the one stable source of nonparental adults left for many American youth. Unfortunately, the sheer size and bureaucratic nature of most junior high schools—coupled with the stereotypes many adults hold regarding the negative characteristics of adolescents—can lead teachers to distrust their students and to withdraw from them emotionally (see Eccles et al., 1993; C. L. Miller et al., 1990). Consequently, these youth have little choice but to turn to peers as nonparental guides in their exploration of alternative identities. Evidence from a variety of sources suggests that this can be a very risky venture.

The reduced opportunity for close relationships between students and junior high school teachers has another unfortunate consequence for young adolescents: It decreases the likelihood that teachers will be able to identify students on the verge of getting into serious trouble and then to get these students the help they need. In this way, the holes in the safety net may become too big to prevent unnecessary “failures.” Successful passage through this period of experimentation requires a tight safety net carefully monitored by caring adults—adults who provide opportunities for experimentation without letting the youth seriously mortgage their futures in the process. Clearly, the large, bureaucratic structure of the typical junior high and middle school is ill suited to such a task.

Third, junior high school teachers (again compared to elementary school teachers) feel less effective as teachers, especially for low-ability students. For example, the seventhgrade junior high teachers studied by Midgley, Feldlaufer, and Eccles (1988) expressed much less confidence in their teaching efficacy than did sixth-grade elementary school teachers in the same school districts. In addition, those students who experienced a decline in their teachers’sense of efficacy as they made the junior high school transition lowered their estimates of their math abilities more than did other students (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989a). This decline in teachers’ sense of efficacy for teaching less competent students could help explain why it is precisely these students who give up on themselves following the junior high school transition.

Fourth, junior high school teachers are much more likely than elementary school teachers are to use such teaching practices as whole-class task organization, public forms of evaluation, and between-classroom ability grouping (see Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Such practices are likely to increase social comparison, concerns about evaluation, and competitiveness (see Rosenholtz & Simpson, 1984), which in turn are likely to undermine many young adolescents’ selfperceptions and motivation. These teaching practices also make aptitude differences more salient to both teachers and students, likely leading to increased teacher expectancy effects and both decreased feelings of efficacy and increased entity rather than incremental views of ability among teachers (Dweck & Elliott, 1983). These predictions need to be tested.

Fifth, junior high school teachers appear to use a more competitive standard in judging students’ competence and in grading their performance than do elementary school teachers (see Eccles & Midgley, 1989). There is no predictor of students’ self-confidence and sense of personal efficacy for schoolwork stronger than the grades they receive. If grades change, then we would expect to see a concomitant shift in the adolescents’ self-perceptions and academic motivation; this is in fact what happens. For example, Simmons and Blyth (1987) found a greater drop in grades between sixth and seventh grade for adolescents making the junior high school transition at this point than for adolescents enrolled in K–8 schools. Furthermore, this decline in grades was not matched by a decline in the adolescents’ scores on standardized achievement tests, supporting the conclusion that the decline reflects a change in grading practices rather than a change in the rate of the students’ learning (Kavrell & Petersen, 1984). Imagine what this decline in grades could do to young adolescents’ self-confidence, especially in light of the fact that the material they are being tested on is not likely to be more intellectually challenging.

Finally, several of the changes noted previously are linked together in goal theory. According to goal theory, individuals have different goal orientations when they engage in achievement tasks, and these orientations influence performance, persistence, and response to difficulty. For example, Nicholls and his colleagues (e.g., Nicholls, 1979b; Nicholls, 1989) defined two major kinds of goal orientations: ego-involved goals and task-involved goals. Individuals with ego-involved goals seek to maximize favorable evaluations of their competence and minimize negative evaluations of competence. Questions like “Will I look smart?” and “Can I outperform others?” reflect ego-involved goals. In contrast, with task-involved goals, individuals focus on mastering tasks and increasing one’s competence. Questions such as “How can I do this task?” and “What will I learn?” reflect task-involved goals. Dweck and her colleagues suggested two similar orientations: performance goals (like ego-involved goals), and learning goals (like task-involved goals; e.g., Dweck & Elliott, 1983). Similarly,Ames (1992), Maehr and Midgley (1996), and their students (e.g., Midgley, Anderman, & Hicks, 1995) distinguish between performance goals (like ego-involved goals) and mastery goals (like task-focused goals). With egoinvolved (or performance) goals, students try to outperform others and are more likely to do tasks they know they can do. Task-involved (or mastery-oriented) students choose challenging tasks and are more concerned with their own progress than with outperforming others. All of these researchers argue—and have provided some support—that students learn more, persist longer, and select more challenging tasks when they are mastery-oriented and have task-involved goals (see Eccles et al., 1998, for review).

Classroom practices related to grading practices, support for autonomy, and instructional organization affect the relative salience of mastery versus performance goals that students adopt as they engage in the learning tasks at school. The types of changes associated with the middle grades school transition should precipitate greater focus on performance goals. In support of this, in Midgley et al. (1995), both teachers and students reported that performance-focused goals were more prevalent and task-focused goals less prevalent in middle school classrooms than in elementary school classrooms. In addition, the elementary school teachers reported using task-focused instructional strategies more frequently than did the middle school teachers. Finally, at both grade levels the extent to which teachers were taskfocused predicted the students’ and the teachers’ sense of personal efficacy. Not surprisingly, personal efficacy was lower among the middle school participants than among the elementary school participants.

In summary, changes such as those noted in the preceding discussion are likely to have a negative effect on many students’ school-related motivation at any grade level. But Eccles and Midgley (1989) argued that these types of changes are particularly harmful during early adolescence, given what is known about psychological development during this stage of life—namely, that early adolescent development is characterized by increases in desire for autonomy, peer orientation, self-focus and self-consciousness, salience of identity issues, concern over heterosexual relationships, and capacity for abstract cognitive activity (see Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Simmons and Blyth (1987) have argued that adolescents need a reasonably safe, as well as an intellectually challenging, environment to adapt to these shifts—an environment that provides a “zone of comfort” as well as challenging new opportunities for growth (see Call & Mortimer, 2001, for expanded discussion of the importance of arenas of comfort during adolescence). In light of these needs, the environmental changes often associated with the transition to junior high school seem especially harmful in that they disrupt the possibility for close personal relationships between youth and nonfamilial adults at a time when youth have increased need for precisely this type of social support; they emphasize competition, social comparison, and ability self-assessment at a time of heightened self-focus; they decrease decision-making and choice at a time when the desire for self-control and adult respect is growing; and they disrupt peer social networks at a time when adolescents are especially concerned with peer relationships and social acceptance. We believe the nature of these environmental changes—coupled with the normal course of development—is likely to result in a developmental mismatch because the “fit” between the early adolescents’ needs and the opportunities provided in the classroom is particularly poor, increasing the risk of negative motivational outcomes, especially for those adolescents who are already having academic difficulties.

Based on these general issues and on the research underlying these conclusions, the Carnegie Foundation funded and helped to coordinate several school reform efforts aimed at making middle schools and junior high schools more developmentally appropriate learning environments. By and large, when well implemented, these reforms were effective at both increasing learning and facilitating engagement and positive motivation (Jackson & Davis, 2000).

Long-Term Consequences of the Junior High School Transition

The work reviewed in the previous section documents the immediate importance of school transitions during the early years of adolescence. Do these effects last? Are there longterm consequences of either a positive or negative experience during this early school transition? There have been very few studies that can answer this question. Some of the work reviewed earlier indicated that a decline in school grades at this point is predictive of subsequent high school dropout. Eccles and her colleagues have gone one step further towards answering this question. First they linked self-esteem change over the junior high school transition to changes in other aspects of mental health and well-being during the transitional period. Second, they linked changes in self esteem over this transition to indicators of mental health, academic performance, and alcohol and drug use in Grades 10 and 12 (Eccles, Lord, Roeser, Barber, & Jozefowicz, 1997). In both sets of analyses, there was a strong association between self-esteem change and other indicators of well-being.

In their first set of analyses, Eccles et al. (1997) found that those students who showed a decline in their self esteem as they made the junior high school transition also reported higher levels of depression, social self-consciousness, school disengagement, worries about being victimized, and substance abuse at the end of their seventh-grade school year. These same students also showed lower self-esteem and more depression during their 10th- and 12th-grade school years and were slightly less likely to be target for graduating from high school on time.

The High School Transition

Although less work has been performed on the transition to high school, the existing work is suggestive of similar problems (Jencks & Brown, 1975). For example, high schools are typically even larger and more bureaucratic than are junior high schools and middle schools. Bryk, Lee, and Smith (1989) provided numerous examples of how the sense of community among teachers and students is undermined by the size and bureaucratic structure of most high schools. There is little opportunity for students and teachers to get to know each other, and—probably as a consequence—there is distrust between them and little attachment to a common set of goals and values. There is also little opportunity for the students to form mentor-like relationships with a nonfamilial adult, and little effort is made to make instruction relevant to the students. Such environments are likely to further undermine the motivation and involvement of many students, especially those not doing particularly well academically, those not enrolled in the favored classes, and those who are alienated from the values of the adults in the high school. These hypotheses need to be tested.

Recent international comparative work by Hamilton (1990) also points to the importance of strong apprenticeship programs that provide good mentoring and solid links to post–high-school labor markets for maintaining motivation to do well in school for non–college-bound adolescents. By comparingtheapprenticeshipprogramsinGermanywiththose in the United States, Hamilton has documented how the vocational educational programs in the United States often do not servenon–college-bound youth very well, either while they are in high school or after they graduate and try to find jobs.

Most large public high schools also organize instruction around curricular tracks that sort students into different groups. As a result, there is even greater diversity in the educational experiences of high school students than of middle grades students; unfortunately, this diversity is often associated more with the students’ social class and ethnic group than with differences in the students’ talents and interests (Lee & Bryk, 1989). As a result, curricular tracking has served to reinforce social stratification rather than foster optimal education for all students, particularly in large schools (Dornbusch, 1994; Lee & Bryk, 1989). Lee and Bryk (1989) documented that average school achievement levels do not benefit from this curricular tracking. Quite the contrary—evidence comparing Catholic high schools with public high schools suggests that average school achievement levels are increased when all students are required to take the same challenging curriculum. This conclusion is true even after one has controlled for student selectivity factors. A more thorough examination of how the organization and structure of our high schools influences cognitive, motivational, and achievement outcomes is needed.

Gender and Achievement

The relation of gender to achievement is a massive and complex topic. Even defining what is included under the topic of achievement is complex. For this research paper, we limit the discussion to school-related achievement and both educational and career planning during the adolescent and young adult years, focusing on the gendered patterns associated with these objective indicators of achievement. But even within this limited scope, the relation of gender to achievement is complex. The patterns of gender differences are not consistent across ages and there is always greater variation within gender than across gender. The relation of gender to achievement is even more complex. To make sense of this heterogeneity, we present the findings in relation to the Eccles et al. “expectancy-value model of achievement-related choices,” with a specific focus on the ways in which gender as a social system influences individual’s self-perceptions, values, and experiences (see Eccles, 1987).

We also limit the discussion to studies focused primarily on European Americans because they are the most studied population. Studies on gender differences in achievement in other populations are just becoming available, and even these are focused on only a limited range of groups. In addition, none of the existing studies on other populations have the range of constructs we talk about in this entry—making comparisons offindingsacrossgroupsimpossibleatthispointintime.More work is desperately needed to determine the generalizability of these patterns to other cultural and ethnic groups.

Gender and Academic Achievement

Over the last 30 years, there have been extensive discussions in both the media and more academic publication outlets regarding gender differences in achievement. Much of this discussion has focused on how girls are being “shortchanged” by the school systems. Recently, the American Association of University Women (AAUW; 1992) published reports on this topic. This perspective on gender inequity in secondary schools has been quite consistent with larger concerns being raised about the negative impact of adolescence on young women’s development. For example, in recent reports, the AAUW reported marked declines in girls’ self-confidence during the early adolescent years. Similarly, Gilligan and her colleagues (Gilligan, Lyons, & Tammer, 1990) have reported that girls lose confidence in their ability to express their needs and opinions as they move into the early adolescent years—she refers to this process as losing one’s voice (see also Pipher, 1994).

However, in the 1960s, the big gender equity concern focused on how schools were “shortchanging” boys. Concerns were raised about how the so-called “feminized culture” in most schools fit very poorly with the behavioral styles of boys—leading many boys to become alienated and then to underachieve. The contrast between these two pictures of gender inequities in school was recently highlighted by Sommers in an article in the May 2000 issue of the Atlantic Monthly.

So what is the truth? Like most such situations, the truth is complex. On the one hand, female and male youth (both children and adolescents) on average fare differently in American public schools in terms of both the ways in which they are treated and their actual performance. On the other, it is not the case that one gender is consistently treated less equitably than the other is: Female and male youth appear to be differentially advantaged and disadvantaged on various indicators of treatment and performance. In terms of performance, females earn better grades, as well as graduate from high school, attend and graduate from college, and earn master’s degrees at higher rates than males. In contrast, males do slightly better than females do on standardized tests— particularly in math and science—and obtain more advanced degrees than do women in many areas of study, particularly in math-related, computer-related, engineering, and physical science fields. Men also are more likely than are women to obtain advanced graduate degrees in all fields except the social sciences and education. These patterns are more extreme in European American samples than in samples of some other ethnic groups within the United States of America.

In terms of treatment, in most ethnic groups in the United States, boys are more likely than girls are to be assigned to all types of special-remedial education programs, and to either be expelled from or forced to drop out of school before high school graduation (National Center on Educational Statistics, 1999). Low-achieving boys (in both European American and African American samples) receive more negative disciplinary interactions from their teachers than do students in any other group—disproportionately more than their “fair” share. In addition, in most studies of academic underachievers, male youth outnumber female youth two to one (McCall, Evahn, & Kratzer, 1992). In contrast, high-achieving boys (particularly European American high-achieving boys) receive more favorable interactions with their teachers than do students in any other group and are more likely to be encouraged by their teachers to take difficult courses, to apply to top colleges, and to aspire to challenging careers (Sadker & Sadker, 1994).

More consistent gender differences emerge for college major and for enrollment in particular vocational educational programs. Here the story is one of gender-role stereotyping. European American women and men are most likely to specialize or major in content areas that are consistent with their gender–roles—that is, in content areas that are most heavily populated by members of their own gender. This gendered pattern is especially marked in vocational education programs for non–college-bound youth; for physical science, engineering, and computer science majors; and for professional degrees in nursing, social welfare, and teaching. Again this pattern is less extreme in other ethnic groups. Finally, there has been substantial movement of women into previously male-dominated fields like medicine, law, and business over the last 20 years (Astin & Lindholm, 2001).

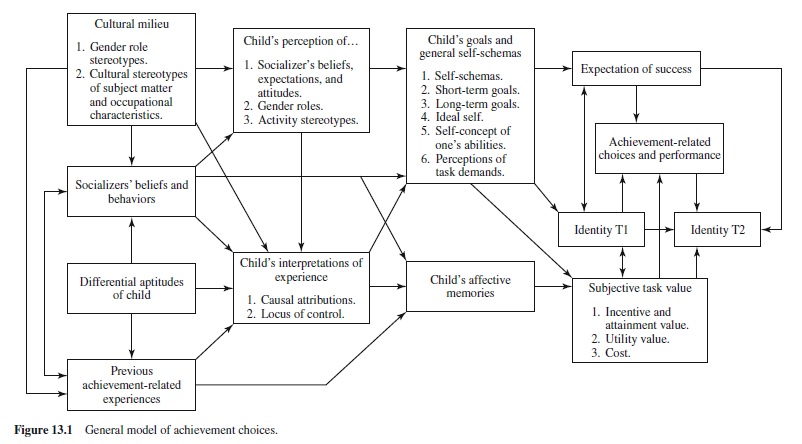

Why do these gendered matters in educational and occupational aspirations exist? Discussing all possible mediating variables is beyond the scope of a single research paper. Instead, we focus on a set of social and psychological factors related to the Eccles’ “expectancy-value model of achievement-related choices and performance” (see Figure 13.1).

Eccles’ Expectancy-Value Model of Achievement-Related Choices and Performance

Over the past 20 years, Eccles and her colleagues have studied the motivational and social factors influencing such achievement goals and behaviors as educational and career choices, recreational activity selection, persistence on difficult tasks, and the allocation of effort across various achievementrelated activities. Given the striking gender differences in educational, vocational, and avocational choices, they have been particularly interested in the motivational factors underlying males’ and females’ achievement-related decisions. Drawing upon the theoretical and empirical work associated with decision-making, achievement theory, and attribution theory, they elaborated a comprehensive theoretical model of achievement-related choices that can be used to guide subsequent research efforts. This model, depicted in Figure 13.1, links achievement-related choices directly to two sets of beliefs: the individual’s expectations for success and the importance or value the individual attaches to the various options perceived by the individual as available. The model also specifies the relation of these beliefs to cultural norms, experiences, and aptitudes—and to those personal beliefs and attitudes that are commonly assumed to be associated with achievement-related activities by researchers in this field. In particular, the model links achievement-related beliefs, outcomes, and goals to interpretative systems like causal attributions, to the input of socializers (primarily parents, teachers, and peers), to gender-role beliefs, to self-perceptions and selfconcept, to personal and social identities and to one’s perceptions of the task itself.

For example, consider course enrollment decisions. The model predicts that people will be most likely to enroll in courses that they think they can master and that have high task value for them. Expectations for success (and a sense of domain-specific personal efficacy) depend on the confidence the individual has in his or her intellectual abilities and on the individual’s estimations of the difficulty of the course. These beliefs have been shaped over time by the individual’s experiences with the subject matter and by the individual’s subjective interpretation of those experiences (e.g., does the person think that her or his successes are a consequence of high ability or lots of hard work?). Likewise, Eccles et al. assume that the value of a particular course to the individual is influenced by several factors. For example, does the person enjoy doing the subject material? Is the course required? Is the course seen as instrumental in meeting one of the individual’s long- or short-range goals? Have the individual’s parents or counselors insisted that the course be taken, or— conversely—have other people tried to discourage the individual from taking the course? Is the person afraid of the material to be covered in the course? The fact that women and men may differ in their choices is likely to reflect gender differences in a wide range of predictors, mediated primarily by differences in self-perceptions, values, and goals rather than motivational strength, drive, or both.

Competence and Expectancy-Related Self-Perceptions

In the last 30 years, there has been considerable public attention focused on the issue of young women’s declining confidence in their academic abilities. In addition, researchers and policy makers interested in young women’s educational and occupational choices have stressed the potential role that such declining confidence might play in undermining young women’s educational and vocational aspirations, particularly in the technical fields related to math and physical science. For example, these researchers suggested that young women may drop out of math and physical science because they lose confidence in their math abilities as they move into and through adolescence—resulting in women who are less likely than are men to pursue these types of careers. Similarly, these researchers suggest that gender differences in confidence in one’s abilities in other areas underlie gender differences across the board in educational and occupational choices. Finally, Eccles and her colleagues suggested that the individual differences in women’s educational and occupational choices are related to variations among women in the hierarchy of women’s confidence in their abilities across different domains (Eccles, 1994).

But do females and males differ on measures commonly linked to expectations for success, particularly with regard to their academic subjects and various future occupations? And are females more confident of their abilities in female genderrole stereotyped domains? In most studies, the answer is yes. For example, both Kerr (1985) and Subotnik and Arnold (1991) found that gifted European American girls were more likely to underestimate their intellectual skills and their relative class standing than were gifted European American boys—who were more likely to overestimate theirs.

Gender differences in the competence beliefs of more typical samples are also often reported, particularly in genderrole stereotyped domains and on novel tasks. Often these differences favor the males. For example, in the studies of Eccles, Wigfield and their colleagues (see also Crandall, 1969), high-achieving European American girls were more likely than were European American boys to underestimate both their ability level and their class standing; in contrast, the European American boys were more likely than were European American girls to overestimate their likely performance. When asked about specific domains, the gender differences depended on the gender-role stereotyping of the activity. For example, in the work by Eccles and her colleagues, European American boys and young men had higher competence beliefs than did their female peers for math and sports, even after all relevant skill-level differences were controlled; in contrast, the European American girls and young women had higher competence beliefs than did European American boys for reading, instrumental music, and social skills—and the magnitude of differences sometimes increase and sometimes decrease following puberty (Eccles, Adler, & Meece, 1984; Jacobs, Lanza, Osgood, Eccles, & Wigfield, 2002).

Furthermore, in these studies, the young women, on average, had greater confidence in their abilities in reading and social skills than in math, physical science, and athletics; and, when averaged across math and English, the male students had lower confidence than did their female peers in their academic abilities in general. By and large, these gender differences were also evident in preliminary studies of African American adolescents (Eccles, Barber, Jozefowicz, Malanchuk, & Vida, 1999). This could be one explanation for the fact that the young men in these samples—as in the nation more generally—are more likely to drop out of high school than were the young women.

Finally, the European American female and male students in the Eccles and Wigfield studies ranked these skill areas quite differently: for example, the girls rated themselves as most competent in English and social activities and as least competent in sports; the boys rated themselves as most competent by a substantial margin in sports, followed by math, and then social activities; the boys rated themselves as least competent in English (Eccles et al., 1993; Wigfield et al., 1998). Such within-gender, rank-order comparisons are critically important for understanding differences in life choices. In the follow-up studies of these same youths, Jozefowicz, Barber, and Eccles (1993) were able to predict within-gender differences in the young women’s and men’s occupational goals with the pattern of their confidences across subject domains. The youth who wanted to go into occupations requiring a lot of writing, for example, had higher confidence in their artistic and writing abilities than in their math and science abilities. In contrast, the youth who wanted to go into science and advanced health-related fields (e.g., becoming a physician) had higher confidence in their math and science abilities than in their artistic and social abilities (see Eccles et al., 1997).

One of the most interesting findings from existing studies of academic self-confidence is that the gender differences in self-perceptions are usually much larger than one would expect, given objective measures of actual performance and competence. First, consider mathematics: With the exception of performance on the most anxiety-provoking standardized test, girls do as well as boys do on all measures of math competence throughout primary, secondary, and tertiary education. Furthermore, the few gender differences that do exist have been decreasing in magnitude over the last 20 years and do not appear with great regularity until late in the primary school years. Similarly, the gender difference in perceived sports competence is much larger (accounting for 9% of the variance in one of our studies) than was the gender difference in our measures of actual sport-related skills (which accounted for between 1–3% of the variance on these indicators).

So why do female students rate their math and sports competence so much lower than their male peers do and so much lower than they rate their own English ability and social skills? Some theorists have suggested that female and male students interpret variations in their performance in various academic subjects and leisure activities in a gender-role stereotyped manner. For example, females might be more likely to attribute their math and sports successes to hard work and effort and their failures in these domains to lack of ability than males; in contrast, males might be more likely than females to attribute their successes to natural talent. Similarly, females might be more likely to attribute their English and social successes to natural ability. Such differences in causal attributions would lead to both the between- and within-gender differences in confidence levels reported in the preceding discussion.

The evidence for these differences in causal attributions is mixed (Eccles-Parsons, Meece, Adler, & Kaczala, 1982; see Ruble & Martin, 1998). Some researchers find that European American females are less likely than European American males are to attribute success to ability and more likely to attribute failure to lack of ability. Others have found that this pattern depends on the kind of task used—occurring more with unfamiliar tasks or stereotypically masculine achievement tasks. The most consistent difference occurs for attributions of success to ability versus effort: European American females are less likely than are European American males to stress the relevance of their own ability as a cause of their successes. Instead, European American females tend to rate effort and hard work as a more important determinant of their success than ability. We find it interesting that their parents do also (Yee & Eccles, 1988). There is nothing inherently wrong with attributing one’s successes to hard work. In fact, Stevenson and his colleagues stress that this attributional pattern is a major advantage that Japanese students have over American students (Stevenson, Chen, & Uttal, 1990). Nonetheless, it appears that within the context of the United States, this attributional pattern undermines students’ confidence in their ability to master increasingly more difficult material—perhaps leading young women to stop taking mathematics courses prematurely.

Gender differences are also sometimes found for locus of control. For example, in Crandall et al. (1965), the girls tended to have higher internal locus of responsibility scores for both positive and negative achievement events, and the older girls had higher internality for negative events than did the younger girls. The boys’ internal locus of responsibility scores for positive events decreased from 10th to 12th grade. A result of these two developmental patterns was that older girls accepted more blame for negative events than the older boys did (Dweck & Repucci, 1973). Similarly, Connell (1985) found that boys attributed their (negative) outcomes more than girls did to either powerful others or unknown causes in both the cognitive and social domains.

This greater propensity for girls to take personal responsibility for their failures, coupled with their more frequent attribution of failure to lack of ability (a stable, uncontrollable cause) has been interpreted as evidence of greater learned helplessness in females (see Dweck & Elliott, 1983). However, evidence for gender differences on behavioral indicators of learned helplessness is quite mixed. In most studies of underachievers, boys outnumber girls two to one (see McCall et al., 1992). Similarly, boys are more likely than girls are to be referred by their teachers for motivational problems and are more likely to drop out of school before completing high school. More consistent evidence exists that females (compared to males) select easier laboratory tasks, avoid challenging and competitive situations, lower their expectations more following failure, shift more quickly to a different college major when their grades begin to drop, and perform more poorly than they are capable of on difficult, timed tests (see Dweck & Elliott, 1980; Parsons & Ruble, 1977; Ruble & Martin, 1998; Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1995).

Somewhat related to constructs like confidence in one’s abilities, personal efficacy, and locus of control, gender differences also emerge regularly in studies of test anxiety (e.g., Douglas & Rice, 1979; Meece, Wigfield, & Eccles, 1990). However, Hill and Sarson (1966) suggested that boys may be more defensive than are girls about admitting anxiety on questionnaires. In support of this suggestion, Lord, Eccles, and McCarthy (1994) found that test anxiety was a stronger predictor of poor adjustment to junior high school for boys, even though the girls reported higher mean levels of anxiety.

Gender-role stereotyping has also been suggested as a cause of the gender differences in academic self-concepts.The extent to which adolescents endorse the European American cultural stereotypes regarding which gender is likely to be most talented in each domain predicts the extent to which European American females and males distort their ability self-concepts and expectations in the gender-stereotypical direction. S. Spencer, Steele, and Quinn (1999) suggested a mechanism linking culturally based gender stereotypes to competence through test anxiety: stereotype vulnerability. They hypothesized that members of social groups (like women) stereotyped as being less competent in a particular subject area (like math) will become anxious when asked to do difficult problems because they are afraid the stereotype may be true of them. This vulnerability is also likely to increase females’ vulnerability to failure feedback on male-stereotyped tasks,leadingtoloweredself-expectationsandself-confidence in their ability to succeed for these types of tasks. To test these hypotheses, S. Spencer, Steele, and Quinn gave college students a difficult math test under two conditions: (a) after being told that men typically do better on this test or (b) after being told that men and women typically do about the same. The women scored lower than the men did only in the first condition. Furthermore, the manipulation’s effect was mediated by variations across condition in reported anxiety. Apparently, knowing that one is taking a test on which men typically do better than women do increases young women’s anxiety, which in turn undermines their performance. This study also suggests that changing this dynamic is relatively easy if one can change the women’s perception of the gender-typing of the test.

In sum, when either gender differences or within-gender individual differences emerge on competence-related measures for academic subjects and other important skill areas, they are consistent with the gender-role stereotypes held by the group being studied (most often European Americans). These differences have also been found to be important mediators of both gender differences and within-gender individual differences in various types of achievement-related behaviors and choices. Such gendered patterns are theoretically important because they point to the power of genderrole socialization processes as key to understanding both girls’ and boys’ confidence in their various abilities. And to the extent that gender-role socialization is key, it is important to study how and why young women differ in the extent to which they are either exposed to these socialization pressures or resist them when they are so exposed.

But even more important is that all of the relevant studies have documented extensive variation within each gender. Both females and males vary a great deal among themselves in their intellectual confidence for various academic domains. They also vary considerably in their test anxiety, their attributional styles, and their locus of control. Such variations within each gender are a major set of predictors of variation among both young men and young women in their educational and occupational choices. European American adolescent males and females who aspire to careers in math and science and who take advanced courses in math and physical science have greater confidence in their math and science abilities than those who do not. They also have just as much—if not more—confidence in their math and science abilities as in their English abilities (see Eccles et al., 1998).

Gendered Differences in Achievement Values