View sample risk behaviors in adolescence research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Adolescence is a time of life marked by change and rapid development. In fact, few developmental periods are characterized by so many changes at so many different levels as is adolescence. These changes are associated with pubertal development and the emergence of reproductive sexuality; social role redefinitions; cognitive, emotional, and moral development; and school transitions (e.g., Hamburg, 1974; Lerner, 1995; Simmons & Blyth, 1987).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The purpose of this research paper is to examine risk and protective factors within adolescents and their environments and the manifestation of those factors in terms of risk behaviors or resiliency. Presented first is a detailed exploration of four major risk behaviors in adolescents (i.e., teenage sexual activity, alcohol and substance use/abuse, delinquency and antisocial behavior, and school failure) and the risk factors found to be associated with them. The comorbidity of those behaviors and factors is also discussed. The paper then investigates the beginning of resiliency research and follows the field’s development through to its current status and theoretical understanding of resiliency. Also discussed are the empirical findings related to protective factors and their interaction with risk factors. Finally, directions for future research are presented.

We hope that readers will gain a clearer understanding of the factors that enhance positive development and those factors that inhibit positive development. This research paper strives to provide specific attention to the major risks as well as their comorbidity. Understanding risk behaviors forms a foundation that fosters our understanding of the influence of risk behaviors on the developmental trajectory of young people. Moreover, specific attention to major risk behaviors also offers a basis for understanding the importance of multiple ecological influences, multiple constitutional influences, and the interactions that occur between them. These interactions are critical to the overall development of adolescents, both in positive and negative directions. In addition, understanding why so many are able to overcome adversity provides us with some direction in intervention efforts. Clearly, the ability to intervene within contexts that comprise the adolescents’ world is essential if we are to create opportunities that will promote the positive development of young people.

Risk Behaviors and Risk Factors

The term risk behavior refers to any behaviors or actions that have the potential to compromise the biological and psychosocial aspects of a developmental period. Involvement in risk behaviors jeopardizes several areas of human development: (a) physical health, physical growth; (b) the accomplishment of normal developmental tasks; (c) the fulfillment of expected social roles; (d) the acquisition of essential skills; (e) the achievement of a sense of adequacy and competence; and (f) the appropriate preparation for the next developmental period of the life span, (i.e., young adulthood for adolescents; e.g., Jessor, Turbin, & Costa, 1998).

The literature provides evidence that risk pertains to the relationship between the individual and the context (e.g., Elliott & Eisdorfer, 1982; Masten, 2001; Werner & Smith, 1992). Moreover, research has found that possession of a particular instance or level of either individual characteristics or embeddedness in a specific context affords different probabilities of experiencing risk (e.g., Dohrenwend, Dohrenwend, Pearlin, Clayton, & Hamburg, 1982; Garbarino, 1994). Risk characteristics refer, then, to those individual and contextual characteristics associated with a decreased likelihood of healthy psychosocial and physical development. Outcome behaviors might include dropping out of high school, delinquency, teen pregnancy, violence, and crime (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Masten, 2001; Schorr, 1988); these behaviors may result in outcomes such as unemployability, prolonged welfare dependency, incarceration, and a shortened life span.

Conducting a meta-analysis of the risk behavior research, Dryfoos (1990) found four distinct categories of risk behavior during adolescence: delinquency, crime, and violence; substance use; teenage pregnancy and parenting; and school failure and dropout. Moreover, Irwin and Millstein (1991) provided support for the findings of Dryfoos’s research regarding substance use and teenage pregnancy as major risk behaviors.

Social scientists have progressed through several stages in their approach to understanding covariates of risks (e.g., Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Werner & Smith, 1992). In the initial stage of investigation, researchers emphasized simple bivariate associations, such as a link between factors like low birth weight or a stressful life event (e.g., parental discord) and a single risk behavior (e.g., drug use). Borrowing from the field of epidemiology, several social scientists moved beyond bivariate associations and employed an approach to studying risk behaviors and their covariates that suggested that there are probably many diverse paths that lead to the development of particular risk behaviors (e.g., Irwin & Millstein, 1991; Masten, 2001; Newcomb, Maddahian, Skager, & Bentler, 1987). Indeed, efforts to find a single covariate may not be useful because most behaviors have multiple covariates (e.g., Perry, 2000). Thus, researchers in the social sciences have moved from a bivariate model of risk/vulnerability to a multivariate model, one that emphasizes the possibility of interactions among variables, such as the co-occurrence of parental addiction (e.g., alcoholism), poverty, and youth problem behaviors (e.g., aggression and school problems; e.g., Masten, 2001; Werner & Smith, 1992).

Although there are variations in the definitions of risk, risk factors, and risk behavior correlates, the research on risk behaviors provides support for the presence of associations among certain individual and contextual characteristics with adolescents’ involvement in risk behaviors. These two types of characteristics are examined here in terms of their relationship to the above-mentioned four categories of risk behavior specified by Dryfoos (1990): teenage sexual activity, alcohol and substance use/abuse, delinquency and antisocial behavior, and school failure.

Teenage Sexual activity

The 1970s and 1980s saw a steady increase in the number of teenagers in the United States who were sexually active (Child Trends, 2001). However, the most recent trend data from the National Center for Health Statistics show a steady decline in the teen birthrate (Child Trends, 2001). The 2000 rate of 48.7 births per 1,000 females ages 14 to 19 is 22% lower than the 1991 rate of 61/1,000 (Child Trends, 2001). Despite these declines the United States has one of the highest teen birthrates of all the developed countries (Child Trends, 2001). For example, a recent report concerning the incidence of sexual intercourse among adolescents younger than age 15 reported rates ranging from 12% to 55% (Meschke, Bartholomae, & Zentall, 2000). By age 19 there is a marked increase in these rates: 85% of males and 77% of females have had sexual intercourse at least once (Moore, Driscoll, & Lindberg, 1998).

This increase in sexual experimentation during adolescence has been coupled with adolescents’frequent use of contraception. By 1995 three quarters of teens reported using some form of contraception at first sex (Abma, 1999). However, youth who are sexually active fail to engage in safe sex (e.g., sex with a condom). Thus, they are more likely to contractAIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and become pregnant during adolescence (Abma, 1999; Meschke et al., 2000). The number of cases of STDs has been increasing since the 1970s, and adolescents account for one quarter of the estimated 12 million cases of STDs that occur annually (e.g., Meschke et al., 2000). Research has further identified the antecedents and correlates of sexual intercourse during the adolescent years, the onset of sexual intercourse, and the use of contraception (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989; Catalano, Bergund, Ryan, Lonczak, & Hawkins, 1999; Dryfoos, 1990; Jessor, 1998; Luster & Small, 1994).

Individual Characteristics

Numerous individual characteristics are associated with adolescent sexual activity. Generally, boys have sexual intercourse at an earlier age than girls (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Perry, 2000). Timing of pubertal maturation has also been linked to early sexual activity (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989; Irwin & Millstein, 1991). Not surprisingly, both males and females who undergo maturation earlier than their peers initiate sexual intercourse earlier than their age-related peers (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989). The earlier the age of initiation, the more likely it is that an adolescent female will become pregnant or contract an STD. Likewise, the earlier the age of initiation, the more likely an adolescent male is to impregnate a female or contract an STD because both are less likely to use any type of contraception (e.g., Luster & Small, 1994; Ozer, Brindis, Millstein, Knopf, & Irwin, 1998; Perry, 2000).

Ethnicity has also been found to be associated with early sexual activity (Irwin & Millstein, 1991).There is a disproportionate representation of African American adolescents who are sexually active and who experience negative outcomes of sexual activity (e.g., teenage pregnancy or STDs; Ozer et al., 1998). On average,AfricanAmerican and Hispanic male adolescents initiate sexual intercourse earlier than their European American counterparts (e.g., Moore et al., 1998; Perkins, Luster, Villarruel, & Small, 1998; Terry & Manlove, 2000). African American females are the most likely to become teen mothers, followed by Latina adolescents and European American adolescents, respectively (e.g., Ozer et al., 1998). It should be noted that ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) covary. When ethnicity is controlled statistically, SES remains associated with adolescent sexual activity. Indeed, low SES is associated with earlier onset of sexual activity (e.g., BrooksGunn & Furstenberg, 1989; Perry, 2000).

Several studies have found a linkage between low aspirations or poor school performance and early engagement in sexual activity (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989; Luster & Small, 1994). In addition, adolescents who lack hope and a positive view of the future are more likely to participate earlier in sexual activity than are those who have a positive view of the future (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Perry, 2000). Adherence to conventional religious values is associated with decreased sexual initiation and behavior (e.g., Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Perkins et al., 1998). Some evidence suggests that self-esteem is usually not reported as a significant factor associated with sexual activity in adolescence (Luster & Small, 1994; Perkins, 1995). However, Orr, Wilbrandt, Brack, Rauch, and Ingersoll (1989) found gender differences in regard to the linkage between teenage sexual activity and selfesteem. Adolescent males who had high self-esteem also had the highest levels of sexual activity; however, the opposite was true for females (Orr et al., 1989). Moreover, adolescent sexual behavior is generally associated with or often preceded by other risk behaviors, such as alcohol and drug use and truancy (e.g., Irwin & Millstein, 1991; Jessor, 1998; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Perry, 2000).

Contextual Characteristics

Research has provided evidence for the association between characteristics of the context and engagement in sexual activity. Adolescents who perceive themselves as having parental support (i.e., communication, accessibility) are less likely to get involved in sexual activity. A similar association has been found between parental monitoring and engagement in sexual activity (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Meschke et al., 2000). Thus, adolescents who are monitored are less likely to engage in sexual activity (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Furstenberg & Hughes, 1995).

Family structure has also been linked with adolescent engagement in sexual activity.Adolescents from single-parent families are more likely to engage in sexual activity and to engage in those activities at an earlier age than are their agerelated peers from two-parent homes (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Furstenberg, 1989; Ketterlinus, Lamb, & Nitz, 1994). However, this association may be confounded by the fact that single-parent families have, on average, considerably lower incomes than two-parent families, as well as the fact that a higher percentage of single-parent families are ethnic minorities than is the case with two-parent families (Calhoun Davis & Friel, 2001). As noted previously, SES (in particular poverty) and ethnicity have been linked to adolescents’ engagement in sexual activity. Studying a sample of 8,266 adolescents living in single-parent families, Benson and Roehlkepartain (1993) found that the association between family structure and adolescent sexual activity exists even when income and ethnicity are held constant. Moreover, a history of sexual or physical abuse has also been found to be associated with adolescent engagement in sexual activity (e.g., Benson & Roehlkepartain, 1993; Perkins et al., 1998).

There is some evidence that peer relations are associated with sexual behavior in adolescence (e.g., Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Perry, 2000; Stättin & Magnusson, 1990). However, peer influence is more strongly related to perceived sexual behavior than to actual behavior (Perry, 2000). Indeed, adolescents (especially girls) who perceive their best friends as sexually active are more likely to be sexually active themselves (e.g., Billy & Udry, 1985). However, Small and Luster (1994) did not find a significant correlation between peer conformity and sexual behavior in adolescence. They suggested that researchers may overestimate the role that peers play in influencing sexual behavior.

Poor neighborhood characteristics are associated with the increased probability of adolescents’ early engagement in sexual activity (e.g., Duncan &Aber, 1997; Kowaleski-Jones, 2000).Adolescents who live in neighborhoods with low monitoring were more likely to become sexually active at an earlier age than were their peers who lived in neighborhoods characterized by high monitoring; thus, nonparental adults in the neighborhood can play an important role in supervising the behavior of adolescents (Small & Luster, 1994).

Alcohol and Substance Use/Abuse

In recent years there have been declines in most alcohol and drug use among adolescents (Johnson, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2001; Kandel, 1991). However, according to data derived from a national sample of high school seniors (Johnson et al., 2001), 52% of 8th graders, 71% of 10th graders, and 80% of 12th graders had tried alcohol, and 15% of 8thgraders, 24% of 10th graders, and 31% of 12th graders had smoked cigarettes. Indeed, in that same study over half had tried an illicit drug, and over one third had used an illicit drug other than marijuana.Furthermore,thearticlestatedthat“bytheendofeighth grade, nearly four in every ten (35%)American eighth graders have tried illicit drugs” (p. 33). Moreover, many adolescents will experiment with cigarettes, chewing tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana (Johnson et al., 2001).

The statistics pertinent to adolescents about frequent or heavy use of alcohol (e.g., having more than two drinks per day or binge drinking, which is five or more drinks in a row three or more times during the past two weeks), about heavy use of cigarettes (smoking five or more cigarettes a day), and about heavy use of illicit drugs (e.g., smoking marijuana 20 times or more in the past 30 days or using cocaine, crack, heroin, or LSD once a week) reflect alarmingly high rates (Johnson et al., 2001). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1998) found that 70.2% of 9th through 12th graders have tried smoking. The Monitoring the Future Study found that “marijuana use rose substantially among secondary school and college students between 1992 and 2000, but somewhat less so among young adults. Nearly one in seventeen (6.0%) twelfth graders is now a current daily marijuana user” (Johnson et al., 2001, p. 45). As noted previously, the abuse of any one of these substances can have harmful short-term and long-term effects on an individual’s physical and mental health (e.g., Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Kandel, 1991).

For adolescents who get heavily involved in drugs (either with one or multiple drugs), the consequences can be devastating, both physically and psychologically. Drug use can severely limit educational, career, and marital success (e.g., Hawkins et al., 1992; Perry, 2000) and has been associated with many societal problems (Dryfoos, 1990; Perry 2000). Indeed, over one third of all automobile fatalities are alcohol related (Perry, 2000). Frequent use of alcohol in the short term is also associated with impaired functioning in school, family problems, depression, and accidental death (e.g., drowning; Perry, 2000).

The heavier the use of a seemingly harmless substance in the early years, the more likely it is that multiple use will occur later (e.g., Johnson et al., 2001; Kandel, 1991). Alcohol and smoking are characterized as gateway drugs because they often lead to more serious substance abuse (e.g., Johnson et al., 2001; Kandel, 1991; Perry, 2000). As with heavy alcohol use, frequent use of marijuana has been linked with the following short-term consequences: impaired psychological functioning, impaired driving ability, and loss of short-term memory.

Over the past 20 years research has identified the antecedents and correlates of alcohol and drug use/abuse during the adolescent years (e.g., Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Johnson et al., 2001; Kandel, 1991). Several studies have identified the individual and contextual characteristics that appear to be associated with alcohol and substance use/abuse in adolescence (e.g., Catalano et al., 1999; Dryfoos, 1990; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Lerner, 1995; Newcomb et al., 1987).

Individual Characteristics

Several individual characteristics have been associated with adolescents’use of alcohol and drugs. Investigators have presented data suggesting that experimentation at an early age leads to a higher risk of using more dangerous drugs (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Johnson et al., 2001; Perry, 2000). The link between ethnicity and alcohol and drug use/abuse is complicated by the underrepresentation of adolescent minorities in empirical research (e.g., African American inner-city youth; Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Dryfoos, 1990). In general, however, European American and Native American adolescents, especially those in urban areas, report the highest rates of alcohol and drug use/abuse, whereas Latino and African American adolescents report intermediate rates of use, and Asian American adolescents report the lowest rates of use (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Newcomb et al., 1987; Ozer et al., 1998).

Low grades in school (especially in junior high school) are associated with an increased likelihood of engagement in alcohol and substance use/abuse (e.g., Hawkins et al., 1992; Ketterlinus et al., 1994; Masten, 2001). Indeed, Hundleby and Mercer (1987) found that good school performance reduced the likelihood of frequent drug use in ninth graders.

However, adolescents who have low educational aspirations are more likely to participate in alcohol and substance use/abuse than those youth who are interested in scholastic achievement, such as attending a postsecondary institution (e.g., Catalano et al., 1999; Newcomb et al., 1987). Several studies have found a linkage between low attendance at church services and the likelihood that adolescents will engage in substance use/abuse (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Perry, 2000).

Involvement in two specific risk behaviors, school failure and antisocial behavior/delinquency, has been associated with alcohol and substance use/abuse. For instance, adolescents who perform poorly in school and who possess low educational aspirations are more likely to become involved in alcohol and substance use/abuse (Dryfoos, 1990; Hawkins et al., 1992). Not surprisingly, then, school failure (defined as being two or more grades behind in school) has been linked with engagement in alcohol and drug use/abuse (e.g., Hawkins et al., 1992; Ketterlinus et al., 1994; Newcomb et al., 1987). School dropout is also related to alcohol and drug use/abuse (Lerner, 2002).

The relationship between antisocial behavior (delinquency) and alcohol and drug use/abuse has been well established (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Jessor, 1998; Johnson et al., 2001). For example, antisocial behavior that is exhibited through fighting, school misbehavior, and truancy in adolescence is linked to an increased likelihood of alcohol and substance abuse (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Farrington, 1998; Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Moreover, several investigators have found that antisocial behavior in the form of lack of law abidance (i.e., delinquency) is associated with alcohol and drug abuse in adolescence (Hawkins et al., 1992).

Contextual Characteristics

A large number of investigations have found evidence for a relationship between the context within which an adolescent is embedded and alcohol and drug use/abuse. Parentaladolescent communication that is characterized by negative patterns (e.g., criticism and lack of praise) has been linked with adolescent engagement in alcohol and drug use/abuse (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Hawkins et al., 1992). In addition, lack of parental monitoring and discipline are related to an increased likelihood of adolescent alcohol and substance use/abuse (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Hawkins et al., 1992; Scheer, Borden, & Donnermeyer, 2000).

Adolescents who have one or both parents who are addicted to a substance are more likely to engage in alcohol and substance use/abuse than are adolescents who do not have an addicted parent or parents (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Resnick et al., 1997). In addition, adolescents who have an older addicted sibling are more likely to get involved in such use than are adolescents who do not have such a sibling (Dryfoos, 1990). There is also a link between parental involvement in a youth’s activities and a decrease in the probability that the adolescent will engage in alcohol and drug use/abuse (e.g., Jessor, 1998; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Resnick et al., 1997).

Consistently, one of the most powerful predictors of adolescent alcohol and drug use/abuse is the behavior of a youth’s best friend (e.g., Borden, Donnermeyer, & Scheer, 2001; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Newcomb et al., 1987). Adolescents whose friends use alcohol and drugs are much more likely to use/abuse them than are those adolescents whose peers do not engage in such behavior. In fact, there is evidence that initiation of alcohol and drug use is through friends rather than strangers (Kandel, 1991).

Delinquency and Antisocial Behavior

The terms antisocial behavior and delinquency suggest a wide range of behaviors, from socially unacceptable but not necessarily illegal acts to violent and destructive illegal behaviors. Two types of offenses will be presented here in regard to criminal acts. First, status offenses are those offenses that are illegal acts due to the age of the individual who commits them. Status offenses are sometimes classified as juvenile offenses, such as running away, truancy, drinking under age, sexual promiscuity, and uncontrollability. Second, index offenses are offenses that are always illegal and are not dependent on age. Thus, index offenses are criminal acts whether they are committed by juveniles or adults and, as categorized by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, include offenses such as robbery, vandalism, aggravated assault, rape, and homicide (Dryfoos, 1990).

Although most individuals with a history of juvenile delinquency do not go on to become convicted criminals, most convicted criminals do have a history of juvenile delinquency (Dryfoos, 1990). Antisocial behavior has been found to be prevalent in general community samples of adolescents (e.g., Tolan, 1988). For example, the FBI reported that juveniles accounted for 17% of all arrests and 16% of all violent crime arrests in 1999. The substantial growth in juvenile violent crime arrests that began in the late 1980s peaked in 1994. Between 1994 and 1999 the juvenile arrest rate for Violent Crime Index offenses fell by 36% (Snyder, 2000).

Approximately one third of juvenile arrests involved younger juveniles (under age 15). The types of crimes committed included arson (67%), followed by sex offenses (51%), vandalism (44%), and other assaults (43%). “Of all the delinquency cases processed by the Nation’s juvenile courts in 1997, 58% involved juveniles younger than 16” (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2001, p. 22). In fact, in the course of a year, an estimated 500,000 to 1.5 million young people run away from or are forced out of their homes, and an estimated 200,000 are homeless and living on the streets (Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, 2001). Past research suggests that the majority of these youth are female (Dryfoos, 1990). Moreover, “in 1999, 27% juvenile arrests involved female offenders arrested. Between 1990 and 1999, the number of female juvenile offenders arrested increased more or decreased less than the number of male juvenile offenders arrested in most offense categories” (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2001, p. 22).

The proportion of violent crimes attributed to juveniles has declined in recent years. The proportion of violent crimes that occurred by juvenile arrests grew from 9% in the late 1980s to 14.2% in 1994 and then declined to 12.4% in 1999. Arrest rates are much higher for African American males than for any other group. African American youths experience rates of rape, aggravated assault, and armed robbery that are approximately 25% higher than those for European American adolescents. Rates of motor vehicle theft are about 70% higher forAfrican Americans, rates of robbery victimization are about 150% higher, and rates of African American homicide are typically between 600% and 700% higher (e.g., National Research Council, 1993; Snyder, 2000).

Self-report data by adolescents indicate a wide gap between rates of self-reported antisocial behavior and juvenile arrest and conviction rates (National Research Council, 1993). The rates of self-report are consistently much higher than are the arrest rates (Dryfoos, 1990). Indeed, a review of the literature on self-report surveys concluded that no more than 15% of all delinquent acts result in police contact (Farrington & West, 1982).The majority of adolescents report that they have participated in various forms of delinquent behavior (Dryfoos, 1990). Dryfoos suggested that the number of index offenses committed by adolescents may be 10 times greater than the number of cases that are discovered and end up in juvenile court. An estimated six million 10- to 17-year-olds reported that within a one-year period they had participated in an act that was against the law; of these, 3.3 million youth were under the age of 14 (Dryfoos, 1990).

Delinquency and antisocial behavior can have harmful short-term and long-term effects on individuals’physical and mental health. Antisocial behavior has been linked with psychiatric problems, early and heavy alcohol and drug use/abuse, and school problems. Over the long term, antisocial behavior is associated with an increased likelihood of adult criminal behavior, unemployment, low occupational status and low income, poor marital adjustment and stability, out-of-wedlock parenting, impaired offspring, and reliance on welfare (e.g., Jessor, 1998; Perry, 2000; Werner & Smith, 1992).

Research has identified the antecedents and correlates of antisocial behavior and delinquency during the adolescent years (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Glueck & Glueck, 1968; Hawkins et al., 2000; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Pakiz, Reinherz, & Frost, 1992). These studies identified the individual and contextual characteristics that appear to be associated with antisocial behavior and delinquency during adolescence. Consensus among researchers about these antecedents and correlates is substantial (Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl, Maguin, Hill, Hawkins, & Abbott, 2001).

Individual Characteristics

Numerous individual characteristics have been associated with antisocial behavior and delinquency during adolescence. Age of initiation in antisocial behaviors has been found to be related to antisocial behavior and delinquency during adolescence. Early onset of adolescent antisocial behavior is associated with high rates of more serious criminal offenses in later adolescence (e.g., Dodge, 2001; Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000).

Studies that have utilized self-reports and arrest statistics have consistently demonstrated that there are large gender differences in the prevalence and incidence of most antisocial and delinquent behaviors. Adolescent males engage in considerably more delinquent behaviors than do adolescent females (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000). This difference is more pronounced in serious and violent crimes. Girls, then, are more likely to be involved in status offenses (e.g., running away) than in serious or violent crimes.

Within the studies using arrest statistics, there is a consistent finding that African Americans are disproportionately represented in the arrest data, victimization reports, and incarceration statistics (e.g., Dodge, 2001; Farrington, 1998; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). However, self-report measures have yielded minimal racial differences in antisocial and delinquent behaviors (National Research Council, 1993).

There is consistent evidence from both cross-sectional and longitudinal research that poor performance in school is associated with antisocial and delinquent behavior (e.g., Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). School failure (being two or more years behind in school or dropping out of school) has been found to be associated with antisocial and delinquent behaviors (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). Furthermore, low educational expectations and aspirations have been linked with an increased likelihood of antisocial and delinquent behaviors in youth (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001).

Employment can provide a legitimate means for obtaining material possessions, acquiring status and career paths, and attenuating the negative effects of poor academic achievement (Duster, 1987). Studies have produced inconsistent data on the association of part-time employment and delinquency. Cross-sectional data provide support for an association between employment and lower levels of antisocial and delinquent behaviors during adolescence (e.g., Dodge, 2001; Tolan, 1988). In the longitudinal literature, however, there is little evidence supporting this association, and, in fact, parttime employment may have deleterious effects on adolescent behaviors (e.g., Mortimer & Johnson, 1998; Perry, 2000).

The research findings are mixed with regard to the individual characteristics of self-esteem. Comparison between delinquents and nondelinquents has provided evidence that delinquent adolescents have lower self-esteem (Arbuthnot, Gordon, & Jurkovic, 1987). However, some studies do not provide evidence for the association between self-esteem and delinquency (e.g., Dodge, 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). In his review of the literature, Henggeler (1989) suggested that the association between self-esteem and delinquency is due to association with a third variable (e.g., intelligence quotients, family relations, or school performance).

As noted in the previous section, numerous studies have established the relationship among antisocial and delinquent behaviors and alcohol and drug use/abuse (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Jessor, 1998). Indeed, antisocial and delinquent behaviors are associated with early and heavy alcohol and substance use/abuse (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Kandel, 1991).

Contextual Characteristics

Research on antisocial and delinquent behavior has provided support for the association among several contextual characteristics and the presence or development of antisocial or delinquent behavior in adolescence. In general, researchers have found a negative linear relationship between parental support (e.g., positive communication, affection) and adolescent antisocial and delinquent behaviors, such that the more parental support that exists, the less likely the adolescent is to be involved in antisocial or delinquent behaviors (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). In addition, many of the already-noted studies found that a significant relationship exists between parental control (e.g., monitoring, discipline) and antisocial and delinquent behaviors (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Farrington, 1998; Henggeler, 1989; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Mahoney & Stättin, 2000). Higher parental monitoring is associated with low instances of antisocial and delinquent behaviors. Moreover, lax or markedly inconsistent discipline has been linked to high rates of antisocial behavior and delinquency (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Glueck & Glueck, 1968; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Hirschi & Stark, 1969).

Parental practice of high-risk behaviors is another characteristic of the parent-adolescent relationship that has been linked to antisocial and delinquent behaviors (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Farrington, 1998; Glueck & Glueck, 1968; Hawkins et al., 2000). Furthermore, parental physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents has been found to be associated with antisocial and delinquent behavior (Brown, 1984). Adolescents who are physically or sexually abused by their parent or parents are more likely to participate in delinquent acts (Brown, 1984; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001).

In addition to the parent-adolescent relationship, other characteristics of the family have been linked with antisocial behaviors and delinquency. For example, there is an association between adolescent antisocial and delinquent behaviors and family support. Low family support, as measured by low warmth and affection among family members, has been linked with antisocial behaviors during adolescence (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000; Henggeler, 1989; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). In addition, several studies have found that antisocial and delinquent behavior is associated with low family cohesion and high family conflict (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Pakiz et al., 1992; Tolan, 1988).

An association has been found between family structure (whether the household is headed by one or two parents) and antisocial behaviors and delinquency (Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Farrington, 1998). For example, adolescents living in mother-only homes and natural parent-stepparent homes were more susceptible to negative peer pressure and engaged in more antisocial behaviors and delinquent acts than did their age-related peers living in homes with two natural parents (Steinberg, 1987). No data have been presented with regard to father-only homes. However, family structure is not as significant in predicting antisocial behavior and delinquency as is the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Farrington, 1998).

For many adolescents, involvement with deviant peers has become a critical aspect of their own delinquent behavior (e.g., Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Mahoney & Stättin, 2000; Perry, 2000). Thus, researchers have found evidence for an association between antisocial behavior and delinquency and engagement with peers who participate in antisocial behaviors and delinquent acts (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). In fact, there is evidence that a high percentage of antisocial and delinquent behavior is carried out with peers (Emler, Reicher, & Ross, 1987).

Certain types of neighborhoods are linked to adolescent antisocial behaviors, to delinquent behaviors, and to delinquent gang activities (e.g., Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Duncan & Aber, 1997; Herrenkohl et al., 2001; Taylor, 1990). Neighborhoods that are located in an area with high crime rates, poverty, and dense living conditions are associated with an increased likelihood of adolescent antisocial behavior and delinquent acts, including the emergence of gangs (e.g., Duncan & Aber, 1997; Henggeler, 1989; Taylor, 1990).

Finally, it should be noted that the impact of SES is unclear. Studies have found evidence for a link between low SES and an increased likelihood of adolescent antisocial behavior and delinquency (e.g., Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998). However, recent studies have not found SES to be of primary importance in predicting adolescent antisocial and delinquent behavior (e.g., Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Tolan, 1988).

School Underachievement and Failure

As noted earlier, low achievement in school has been linked to the three previously mentioned risk behaviors—adolescent sexual activity, alcohol and drug use/abuse, and antisocial behavior and delinquency. In addition, many of the individual and contextual characteristics previously mentioned are linked to school underachievement and failure.

Low school achievement, poor grades, and being overage for grade are often associated with dropping out (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Rumberger, 2001). Yet not everyone who has low grades or is overage drops out. The consequences for poorly equipped high school graduates, however, may inhibit their chances of getting into a postsecondary school, and this, in turn, may limit their chances of getting a well-paying job. High school dropouts are two to three times more likely to be in marginal jobs and to be employed intermittently (Eccles, 1991). Conversely, each added year of secondary education reduces the probability of public welfare dependency in adulthood by 35% (Berlin & Sum, 1988).

School failure here will be defined as possessing poor grades (e.g., half of a student’s grades are D or less in regard to academic content areas) and being retained one or more grades. Although some recent studies have suggested that retention may have some positive effects on academic achievement (Roderick, Bryk, Jacob, Easton, & Allensworth, 1999), falling behind one’s age-related peers has been found in numerous studies to be strongly predictive of dropping out (e.g., Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Jimerson, 1999; Roderick et al., 1999; Rumberger, 2001); even when achievement, SES, and gender are controlled, being held back increases the probability of eventually dropping out of school by 20% to 30% (Smith & Shepard, 1988). Each year, about 5% of all high school students drop out of school (Kaufman, Kwon, Klein, & Chapman, 1999). The majority of adolescents who do eventually drop out of school will encounter long-term employment problems. In 1998 the unemployment rate for dropouts was 75% higher than for high school graduates (United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2000b, Figure 24). Over their lifetimes, each year’s class of dropouts will cost $260 billion in lost earnings and foregone taxes (Catterall, 1987). Thus, there are devastating long-term effects of school failure and dropout.

Individual Characteristics

Several individual characteristics have been found to be related to school failure and dropout. Many studies have found that older adolescents who have been retained (held back) from advancing to the next grade level with their age-related peers are more likely to do poorly in school and to drop out (e.g., Eccles, 1991; Powell-Cope & Eggert, 1994; Rumberger, 2001; Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1999). Furthermore, in general, adolescents’ average course grades decline as they move from primary school into secondary school; that decline is especially marked at each of the school transition points (Simmons & Blyth, 1987).

Females are less likely to be involved in behavior problems in school, and problem behaviors have been linked to school failure and dropout (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Hawkins et al., 2001; Jessor, 1998; National Research Council, 1993). For example, in 1995 males were two-thirds more likely to be retained in a grade than were females (United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1997).

Ethnicity has been linked with trends in achievement, inasmuch as being a member of an ethnic minority increases the probability of school failure and dropout (except for Asian American youth; Eccles, 1991; Kaufman et al., 1999; National Research Council, 1993). Indeed, African American and Latino adolescents have a greater probability of being left behind a grade than do European American students (United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1997; National Research Council, 1993). Simmons and Zhou (1993) obtained similar findings when they examined African American and European American sixth to ninth graders. They found that African American males showed the highest degrees of school problem behavior in general, and probation and suspensions in particular. This higher frequency of minority adolescents failing in school or dropping out may be confounded by the greater incidence of poverty and lower SES among ethnic minorities, especially African Americans and Latinos. Indeed, lower levels of resources and poorer learning environments are more common in high-poverty schools, which are more likely to be attended by minority students (United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1997).

Adolescents who value school less or who have a negative attitude about school are more likely to fail or drop out than are adolescents who value school and possess a positive attitude about school (e.g., Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Powell-Cope & Eggert, 1994; Rumberger, 2001; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Simmons and Zhou (1993), for example, found that at transitions to junior high school and to high school, African Americans’ attitudes toward school dropped relatively precipitously. Not surprisingly, adolescents who have low educational aspirations are more likely to fail at school or to drop out of school (e.g., Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Rumberger, 2001; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Moreover, a lack of basic skills and problem-solving abilities has been linked with school failure and dropout; adolescents who are deficient in basic skills and problem-solving skills have an increased probability of failing or dropping out of school (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Rumberger, 2001).

Steinberg and Darling (1993) found that time spent on homework was associated with school failure. They found that adolescents who spent little or no time on their homework were likely to fail at school. However, Dryfoos (1990) did not find lack of time spent on homework to be a significant correlate of school failure or dropout. Thus, more research is needed to test the association between time spent on homework and school failure or dropout. In turn, other investigations have found that potential school failures and dropouts spend more time socializing, dating, and riding around in cars (e.g., Rumberger, 2001).

An association has been found between self-esteem and school failure and dropout (e.g., Powell-Cope & Eggert, 1994; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Adolescents who have low self-esteem are more likely to do poorly in school and to drop out. Several researchers have identified an association between involvement in school activities and school failure and dropout. Low interest in school activities and low participation in school activities are linked with an increased likelihood of school failure and dropout (e.g., Eccles, 1991; Eccles & Barber, 1999; Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Rumberger, 2001).

Research has also found a link between school failure and dropout and other risk behaviors, such as antisocial behavior and delinquency, alcohol and drug use/abuse, and adolescent sexual activity (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Hawkins et al., 1992; Jessor, 1998; Jimerson, 1999; National Research Council, 1993). As noted previously, adolescent pregnancy is a significant antecedent of dropping out. However, dropping out is also an antecedent of teenage childbearing (e.g., Eccles, 1991; Luster & Small, 1994; Perry, 2000). In addition, antisocial behavior and delinquency have been shown to be associated with an increased likelihood of school failure or dropout (e.g., Farrington, 1998; Hawkins et al., 2000; Henggeler, 1989; Herrenkohl et al., 2001). Furthermore, adolescents who frequently use and abuse alcohol and drugs have been found to have a higher probability of failing or dropping out of school (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Hawkins et al., 2000; Hawkins et al., 1992). The overlapping of these risk behaviors is discussed in the final section of this literature review.

Contextual Characteristics

Several contextual characteristics have been associated with school failure and dropout. Investigators have found a link between parental support (e.g., positive communication, affection) and school failure and dropout. Adolescents who have parental support and are able to discuss issues with their parents are less likely to fail or drop out of school (e.g., Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Dryfoos, 1990; Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; Rumberger, 2001). Moreover, authoritatively reared adolescents are less likely to fail or drop out of school (e.g., Simmons & Blyth, 1987; Steinberg & Darling, 1993). Low parental monitoring is associated with failing school and dropping out (Barnes & Farrell, 1994; Rumberger, 2001). Parental education is also strongly related (Rumberger, 2001). Adolescents whose parents have low levels of education have an increased likelihood of school failure and dropout (e.g., Eccles, 1991; McNeal, 1999; Pong & Ju, 2000; Rumberger, 2001).

There has been inconsistent evidence that family structure is associated with school failure and dropout. Adolescents who are from larger families (e.g., more than two siblings) are more likely to fail or drop out of school than are adolescents from smaller families (McNeal, 1997). This association may be related to the consistently low SES of large families. Adolescents who live in single-parent homes have a higher probability of failing or dropping out of school than do adolescents who live in two-parent homes (e.g., Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999; McNeal, 1999; Rumberger, 2001). However, several studies found that the association of family structure with school failure and dropout was minimal when SES was accounted for in the analysis (e.g., National Research Council, 1993; Pong & Ju, 2000). Thus, the relationship between family structure and school failure and dropout is not clear.

Adolescents who have affiliations with peers who have low expectations for school or have friends who have dropped out are more likely to fail or drop out of school than are adolescents whose peers have high expectations and positive attitudes toward school (e.g., Powell-Cope & Eggert, 1994; Rumberger, 2001; Wang et al., 1999). Moreover, Steinberg and Darling (1993) found that, forAsianAmerican, African American, and Latino adolescents, peers are relatively more influential in their academic achievement than are parents. For European American adolescents, parents were a more potent source of influence (Steinberg & Darling, 1993).

Larger schools and larger classrooms are associated with increased likelihood of school failure and dropout (e.g., Rumberger & Thomas, 2000). In addition, school climate has been found to be associated. Schools that emphasize competition, testing, and tracking and have low expectations have a higher number of school failures and dropouts than do schools that have high expectations, encourage cooperation, and have teachers who are supportive (e.g., Powell-Cope & Eggert, 1994; Rumberger & Thomas, 2000; Rutter, 1979). However, McNeal (1997) found no effect of academic or social climate on high school dropout rates after controlling for the background characteristics of students, social composition, school resources, and school structure.

There has been a lack of consensus and consistency of findings regarding the association between adolescents’ part-time employment and school failure and dropout (e.g., Steinberg & Darling, 1993). For example, D’Amico’s (1984) analysis of the National Longitudinal Study (NLS) youth data demonstrated that employment at low intensity (less than 20 hours per week) lessened dropout rates. However, Steinberg and Avenevoli (1998) found that those who worked more than 20 hours a week were more likely to become disengaged from school. Furthermore, Mortimer and Johnson (1998) found no association between adolescent employment and school failure or dropout.

Afew studies have found some evidence of a positive link between stress/depression and school failure and dropout, such that high stress is associated with school failure and dropout (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Eccles, 1991; Rumberger, 2001; Simmons & Blyth, 1987). For example, Brack, Brack, and Orr (1994) found that females who were failing at school had higher levels of reported stress/depression than those females who were doing average or better; however, they did not find a similar relationship for males.

In his extensive review, Rumberger (2001) provided evidence from several studies that communities influence students’ withdrawal from school. For example, neighborhood characteristics seemed to predict differences in dropout rates among communities, apart from the influence of families (e.g., Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993).

Neighborhoods that are characterized as urban, highdensity, and poverty-stricken are associated with adolescent school failure and dropout (e.g., Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993; Dryfoos, 1990; Eccles, 1991; Schorr, 1988). For example, students in urban areas appeared to drop out at a higher rate than students in rural areas; however, the difference between the rates for these two groups is not statistically significant (United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2000a).

Finally, there is consistent evidence from both crosssectional and longitudinal research that school failure and dropout are associated with low SES (e.g., Eccles, 1991; National Research Council, 1993; Rumberger, 2001; Schorr, 1988). For example, adolescents from low-income families are three times more likely to drop out of school than are children from middle-income families, and they are nine times more likely to drop out of school than students from high-income families (e.g., United States Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics, 2000b).

Co-Occurrence of Risk Behaviors

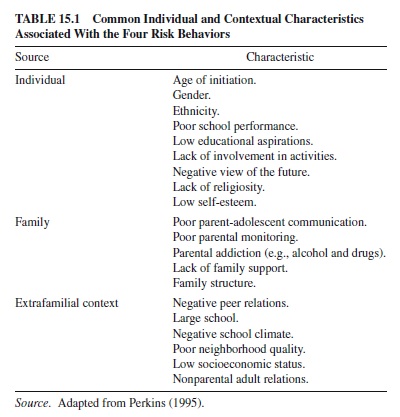

As evidenced earlier, risk behaviors do not exist in isolation; they tend to covary (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Hawkins et al., 2000; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Masten, 2001; Perry, 2000). Moreover, among the previously noted risk behaviors there are common individual and contextual characteristics with which they are associated (e.g., early age of initiation, school underachievement, school misconduct, negative peer behaviors, inadequate parent-adolescent relationships, and low quality neighborhoods). The list of common characteristics has been corroborated by several researchers and is presented in Table 15.1 (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2000; Jessor, 1998; Perry, 2001). In her meta-analysis of the literature on the four risk behaviors noted earlier, Dryfoos (1990), for example, found six overarching characteristics associated with involvement in the four risk behaviors.

First, heavy involvement in risk behaviors and more negative consequences from those behaviors are linked with early initiation or occurrence of any of the risk behaviors. Second, common to all problem behaviors is doing poorly in school and having low expectations of future performance. Third, misconduct in school and other conduct disorders are related to each of the risk behaviors. Fourth, adolescent involvement in any of the risk behaviors is increased when youth have peers that engage in the risk behaviors or when adolescents have a low resistance to peer influence. Fifth, an inadequate parent-adolescent relationship is common to all risk behaviors. Areas that characterize an inadequate relationship are lack of communication, lack of monitoring, inadequate discipline, role modeling of problem behaviors (e.g., exhibiting risk behaviors), and low parental education. Sixth, low quality neighborhoods are associated with involvement in risk behaviors. These neighborhoods are characterized by poverty, violence, urbanization, and high-density conditions.

Several other studies have assessed the co-occurrence of risk behaviors (e.g., Bingham & Crockett, 1996; Farrington & West, 1982; Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Moses, 1995). For instance, in their extensive review of research on alcohol use and alcoholism, Zucker et al. (1995) found that antisocial behavior in adolescence is consistently related to alcoholic behavior. Moreover, findings from the 18-year-long Michigan State University Longitudinal Study have provided evidence that difficulty in achievement-related activity in adolescence is consistently found in youths who later become alcoholics (e.g., Zucker et al., 1995). Bingham and Crockett (1996), who examined adolescent sexual activity longitudinally, have found similar relationships among adolescent sexual activity, antisocial behavior, underachievement, and alcohol use. In addition, they found that the later in ontogeny that adolescents initiated sexual intercourse, the lower was their involvement in other problem behaviors (e.g., antisocial behaviors, alcoholism, and school misconduct).

Clearly, research has found a link between certain characteristics (see Table 15.1), risk factors, and adolescents’ participation in risk behaviors. Yet many adolescents exposed to a context containing some or all of the stated risk factors do not engage in risk behaviors and, in fact, appear to adapt well and live successful lives. Moreover, evidence exists demonstrating that some children thrive despite their high-risk status. This phenomenon has been the focus of much research in the last 30 years.

Resiliency

Social scientists have gone through several stages in their approach to understanding vulnerability and resiliency (Werner & Smith, 1992). Generally, researchers have studied individuals exposed to biological risk factors and stressful life events as the major focus of vulnerability and resiliency research. In the initial stages of research, investigators emphasized the association between a single risk variable, such as low birth weight or a stressful life event (e.g., parental discord), and negative developmental outcomes. Borrowing from the field of epidemiology, several social scientists have more recently employed an approach suggesting that many diverse paths lead to the development of particular risk behaviors (Newcomb et al., 1987) and that efforts to find a single cause may not be useful because most behaviors have multiple causes (e.g., Small & Luster, 1994). Thus, researchers in the social science field have moved from a “main effect” model of vulnerability research to a model that emphasizes interactional effects among multiple stressors, for example, as in the literature that stresses the co-occurrence of parental psychopathology (e.g., alcoholism or mental illness) and poverty (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Werner & Smith, 1992).

Finally, resiliency research has shifted its focus from the emphasis on negative developmental outcomes (e.g., risk behaviors) to an emphasis on successful adaptation in spite of childhood adversity (Luthar, 1991; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Werner & Smith, 1992). Indeed, in the last 25 years developmental psychopathologists and other social scientists have increasingly explored the concept of invulnerability rather than focusing predominantly on vulnerability and maladjustment (Luthar et al., 2000). For example, in the mid1970s, Anthony (1974), a child psychiatrist, introduced the concept of the psychologically invulnerable child into the literature of developmental psychopathology to describe children who, despite a history of severe or prolonged adversity and psychological stress, managed to achieve emotional health and high competence (Werner & Smith, 1992).

However, Rutter (1985) noted that resistance to stress in an individual is relative, not absolute. Thus, an individual’s ability to overcome stress is dependent on the level of the stress not exceeding the level of the individual’s resiliency characteristics. In addition, the bases of resistance to stress are both environmental and constitutional, and the degree of resistance varies over time according to life circumstances (e.g., Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1985). Invulnerability may imply an unbreakable individual, one able to conquer any level of stress. Therefore, the concept of resilience or stress resistance, rather than invulnerability, is preferred by many researchers (e.g., Masten & Garmezy, 1985; Rutter, 1985; Werner & Smith, 1992) because it acknowledges a history of success while also implying the possibility of succumbing to future stressors.

The assumption in these investigations is that resiliency can be displayed or detected only through an individual’s response to adversity, whether it is a stressful life event or a situation of continuous stress (e.g., war, abuse; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998).Accordingly, resilient individuals are well adapted despite serious stressors in their lives (Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2001). Indeed, resilient individuals are those who cope effectively with stresses arising as consequences of their vulnerability; and a balance, congruence, or fit, among risk, stressful life events, and protective characteristics of the individual and the individual’s ecology accounts for the diversity of developmental outcomes (Ford & Lerner, 1992; Kumpfer, 1999). Therefore, studying resiliency involves an examination of the link between the person and the demands of the context in variables, factors, and processes that will either promote or subvert adaptation.

An individual’s ability to adapt to the changes within the environment and to alter the environment is basic to that individual’s survival. Whether situations are marked by high stress or by low stress found in the challenges of daily life, adaptation is a basic function of human development. Resiliency, then, is the organism’s ability to adapt well to its changing environment, an environment that includes stressors (e.g., accidents, death of a loved one, war, and poverty) and daily hassles (e.g., negative peer pressures and grades). Thus, studies of resiliency and risk are investigations about human adaptation to life or about competence. Competence is a generalization about adaptation that implies at the least “good” effectiveness (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998).

Human adaptation or competence is composed of the interplay between the context/ecology and the developing organism (Lerner, 2002; Schneirla, 1957). In resiliency the processes involved in the context/ecology interplay are composed of the interaction over time between the protective factors or risk factors at multiple levels that contributes to the direction of the developmental outcomes, whether positive or negative. This interaction is complex and requires a holistic, comprehensive perspective in order to be adequately examined and understood. Models derived from this perspective posit that there are reciprocal influences between the organism and the context/environment (Schneirla, 1957) and that development occurs through these mutual influences (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Ford & Lerner, 1992; Kumpfer, 1999; Lerner, 2002). Moreover, these models assert that any single explanation of risk-taking behaviors with regard to protective factors and risk factors is too simplistic, in that such explanations are likely to ignore the importance of multiple ecological influences, multiple constitutional influences, and the interactions that develop among them. In fact, several scholars have suggested that the use of the term factor may in fact suggest too static a relationship between risk characteristics, protective characteristics, and risk behaviors (Kumpfer, 1999; Rutter, 1985). Process may be a better way to describe the dynamic nature of risk and protective characteristics.

Resiliency involves competence in the face adversity, but more than that, it involves an assessment based on some criteria of the adaptation as “good” or “OK” (Masten, 2001). These assessment criteria are based on specific cultural norms within the historical and social contexts for the behavior of that age and situation (Luthar & Cushing, 1999). Borrowing from Masten (2001), resiliency is defined “as a class of phenomena characterized by good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or development” (p. 228).

Moreover, resiliency is multidimensional in nature. Thus, one may be resilient in one domain but not exhibit resiliency in another domain. As Luthar et al. (2000) stated, “some high-risk children manifest competence in some domains but exhibit problems in other areas” (p. 548). In a study by Kaufman, Cook, Arny, Jones, and Pittinsky (1994), for example, approximately two thirds of children with histories of maltreatment were academically resilient; however, when examining these same children in the domain of social competence, only 21% exhibited resiliency.

Protective Factors and Resiliency

Risk and resiliency research provides evidence that specific variables and factors are involved in safeguarding and promoting successful development. That is, research has identified particular variables that are responsible for adolescent resiliency in spite of adverse contexts, while, in turn, other variables have been found to promote failure and to encourage participation in risk behaviors (e.g., Garmezy, 1985; Kumpfer, 1999; Luthar, 1991; Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1985; Werner & Smith, 1992). As noted previously in this research paper, risk factors are defined, then, as individual or environmental hazards that increase an individual’s vulnerability to negative developmental behaviors, events, or outcomes (e.g., Masten, 2001; Werner & Smith, 1992). However, the presence of risk factors does not guarantee that a negative outcome will occur; rather, it simply increases the probability of its occurrence (e.g., Garmezy, 1985; Masten, 2001; Werner & Smith, 1992).

The probabilities of a negative outcome vary as a consequence of the presence of protective factors. Such factors buffer, modify, or ameliorate an individual’s reaction to a situation that, in ordinary circumstances, would lead to maladaptive outcomes (Kumpfer, 1999; Masten, 2001; Werner & Smith, 1992). According to this definition, then, a protective factor is evident only in combination with a risk variable. Thus, a protective factor has no effect in low-risk populations, but its effect is magnified in the presence of the risk variable (e.g., Rutter, 1987; Werner & Smith, 1992). In turn, Rutter (1987) suggested that while protective factors may have effects on their own, such factors have an impact on adjustment by virtue of their interaction with risk variables. However, still another possibility is that protective factors can be defined as variables that are linked with an individual experiencing positive developmental outcomes as compared to negative developmental outcomes.

Although there are variations in the definitions of risk, endangerment, risk factors, and protective factors, the research on resilient or stress-resistant children, adolescents, andyoungadultsprovidessupportfortheexistenceofspecific individual and contextual characteristics, namely protective factors (e.g., temperament and social support networks, respectively; Garmezy, 1985; Rutter, 1987; Werner & Smith, 1992). Protective factors are incorporated into adolescents’ lives and enable them to overcome adversity. On the other hand, some individual and contextual variables (e.g., difficult temperament, poverty, and lack of adult support) are risk factors that increase the probability of involvement in risk behaviors (e.g., Garmezy, 1985; Luthar et al., 2000; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Werner & Smith, 1992).

Models of Protective Factors and Processes

It is not known whether protective variables or protective processes have any effect on low-risk populations because the research has focused on high-risk groups (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). Rutter (1987) suggested that a protective variable’s effect may be magnified in high-risk situations. According to this idea, vulnerability and protection are the negative and positive poles of the same processes. Thus, the potential for involvement in risk behaviors is crucial to this definition because without the risk behavior’s presence there is no method of differentiating risk processes from protective processes. Consequently, most resiliency and risk studies have investigated individuals who are living in high-stress situations and life events (e.g., born with low birth weight or living in poverty, war, or economic depression) or who have experienced highly stressful situations (e.g., separation from a parent due to divorce or death, or the experience of physical or sexual abuse; Garmezy, 1985, Masten, 2001). The reason for this focus is that individuals experiencing a lot of stress have a higher probability of involvement in maladaptive behaviors, that is, involvement in risk behaviors (Rutter, 1993). The level of resiliency needed differs depending upon the stressfulness of the ecology of an adolescent. Adolescents who are under severe, multiple stresses (e.g., poverty, parental discord, and maltreatment) will need a higher degree of resiliency or a larger number of protective processes in order to develop positively than would another person who is experiencing mild stress (e.g., difficulty in school). However, the level of stress is also somewhat dependent on the individual’s perception of stress (e.g., Kumpfer, 1999).

Using different models, researchers have described several mechanisms through which protective factors help reduce or offset the adverse effects of risk factors (Zimmerman & Arunkumar, 1994). Three models have been developed by Garmezy (1985): (a) the compensatory model, (b) the inoculation model, and (c) the protective factor model. In the compensatory model, the protective factor does not interact with the risk factor; rather, it interacts with the outcome directly and neutralizes the risk factor’s influence. In the inoculation model each risk factor is treated as a potential enhancer of successful adaptation provided that it is not excessive (Rutter, 1987).This occurs when there is an optimal level of stress that challenges the individual and, when overcome, strengthens the individual. Thus, the relationship between stress and competence is curvilinear:At low or moderate levels of stress competence increases, but at higher levels of stress it decreases (Wang et al., 1999). In the third model the protective factor interacts with the risk factor in reducing the probability of a negative outcome (Zimmerman & Arunkumar, 1994). Thus, the protective factor is acting as a moderator.Although the protective factor may have a direct effect on an outcome, its effect is stronger in the presence of a risk factor. These three models of interaction describe a process that emphasizes the dynamic nature of the relationship between risk characteristics and protective characteristics. Thus, the term process may provide a more adequate description of protective characteristics than the term factor, since the latter implies a static condition.

Identified Protective Factors

In their longitudinal study of a cohort of children from the island of Kauai, Werner and Smith (1992) described three types of protective factors that emerge from analyses of the developmental course of high-risk children from infancy to adulthood: (a) dispositional attributes of the individual, such as activity level and social ability, at least average intelligence, competence in communication skills (language and reading), and internal locus of control; (b) affectional ties within the family that provide emotional support in times of stress, whether from a parent, sibling, spouse, or mate; and (c) external support systems, whether in school, at work, or at church, that reward the individual’s competencies and determination and provide a belief system by which to live.

Bogenschneider (1998) derived similar conclusions in her review of resiliency literature. She concluded that variables operated as protective factors in adolescence at various levels of the ecosystems of youth: (a) individual level—such as welldeveloped problem-solving skills and intellectual abilities; (b) familial level—for example, a close relationship with one parent; (c) peer level—a close friend; (d) school level—positive school experiences; and (e) community level—required helpfulness (e.g., as it occurs when the adolescent is needed to bring in extra income or help manage the home), and a positive relationship with a nonparental adult (e.g., neighbor, teacher).

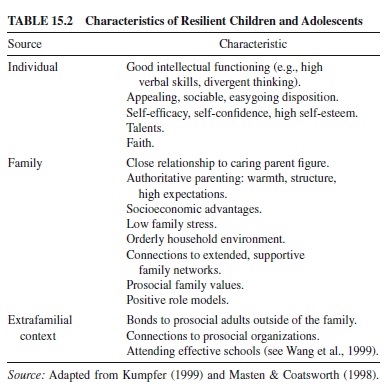

In their extensive review of resiliency research, Masten and Coatsworth (1998) summarized the findings from over 25 years of research. As shown in Table 15.2, they noted that similar protective factors are found across resiliency studies that have been conducted in a wide variety of situations throughout the world (e.g., war, living with parents who have severe mental illness, family violence, poverty, and natural disasters).

Kumpfer’s Resiliency Framework

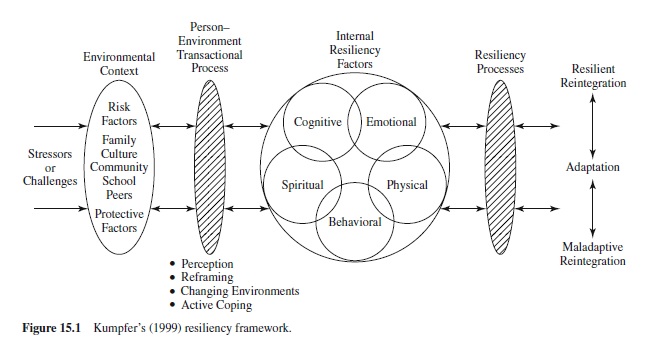

In her recent examination of resiliency, Kumpfer (1999) integrated the work of others into a resiliency framework that employs a transactional model based on the social ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the person-processcontextual model (Ford & Lerner, 1992). According to Kumpfer (1999), this framework is composed of (a) environmental characteristics that are antecedents (i.e., risk and protective factors), (b) characteristics of the resilient person, and (c) the individual’s resilient reintegration or positive outcome after a negative life experience, as well as the dynamic mechanisms that mediate between the person and the environment and the person and the outcome.

Many of the risk factors presented earlier in this research paper reside in the environment. Indeed, high-risk youth are often labeled as such due to a high-risk environment rather than internal high-risk characteristics (Kumpfer, 1999). Protective factors are also found in that same environment. According to Garmezy (1985), microniches of support with adequate growth opportunities for some individuals exist even in these high-risk environments. As noted earlier, protective factors interact with risk factors to act as buffers. The interaction between risk and protective factors describes the first oval of the resiliency framework found in Figure 15.1. Generally, youth adjust reasonably well to one or two risk factors, but beyond two risk factors the likelihood for damage and maladjustment increases rapidly (e.g., Jessor, 1998; Masten, 1999; Rutter, 1993). Conversely, increasing the number of protective processes can help buffer those risk factors (e.g., Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1993, 1997).

The second oval of the resiliency framework shown in Figure 15.1 involves the transactional processes that mediate between a person and his or her environment. This involves the ways a person consciously or unconsciously modifies his or her environment or selectively perceives the environment. Kumpfer (1999) explains this notion thus:

Resilient youth living in high drug and crime communities seek ways to reduce environmental risk factors by seeking the prosocial elements in their environment. They maintain close ties with prosocial family members, participate in cultural and community events, seek to be school leaders, and find non-drug using friends and join clubs or youth programs that facilitate friendships with positive role models or mentors. (p. 191)

Kumpfer (1999) identified some transactional processes that help high-risk youth transform a high-risk environment into a more protective environment. These include selective perception, cognitive reframing, planning and dreaming, identification and attachment with prosocial people, active environmental modifications by the youth, and active coping. For example, Kumpfer suggested that resilient youth seek out nurturing adults who facilitate and foster protective processes by positive socialization or caregiving. According to Kumpfer (p. 192), these caring adults provide that positive socialization through “1) role modeling, 2) teaching, 3) advice giving, 4) empathetic and emotionally responsive caregiving, 5) creating opportunities for meaningful involvement, 6) effective supervision and disciplining, 7) reasonable developmental expectations, and 8) other types of psychosocial facilitation or support.”

Therefore, a transactional process occurs between the environmental context (risk and protective factors) and internal resiliency factors to create the resiliency process or outcome. Through her review, Kumpfer (1999) found that internal resiliency factors involve the following internal characteristics: cognitive (e.g., academic skills, intrapersonal reflective skills, planning skills, and creativity), emotional (e.g., emotional management skills, humor, ability to restore self-esteem, and happiness), spiritual (e.g., dreams/ goals and purpose in life, religious faith or affiliation, belief in oneself and one’s uniqueness, and perseverance), behavioral/social competencies (e.g., interpersonal social skills, problem-solving skills, communication skills, and peer resistant skills), and physical well-being and physical competencies (e.g., good physical status, good health maintenance skills, physical talent development, and physical attractiveness).

The far right of the resiliency framework (Figure 15.1) presents three potential outcomes for the resiliency process (Kumpfer, 1999). Resilient reintegration outcomes involve being made stronger and reaching a higher state of resiliency. Homeostatic reintegration outcomes involve bouncing back to the original state that existed before the stress or crisis occurred. Maladaptive reintegration outcomes involve not demonstrating resiliency, in that the individual functions at a lower state.

The research on resiliency to date has focused on the factors that place individuals at greater risk and the factors that counteract those risk factors. In addition, the insightful criticisms of several scholars (e.g., Masten, 1999; Luthar et al., 2000) have advanced our thinking about the construct, methods, and findings of this work. This research is very useful in that it directs researchers toward potential processes that are worth investigating and toward instruments for analyzing resilience (Masten, 1999). The resiliency research, thus far, also provides us with a greater awareness of the complexity of the concept or resilience (Masten, 2001) because of its integration within the human adaptation system. Indeed, Masten (2001) states,

The great surprise of resilience research is the ordinariness of the phenomena. Resilience appears to be a common phenomenon that results in most cases from the operation of basic human adaptational systems. If those systems are protected and in good working order, development is robust even in the face of severe adversity; if these major systems are impaired, antecedent or consequent to adversity, then the risk for developmental problems is much greater, particularly if the environmental hazards are prolonged. (p. 227)

Future Directions and Conclusions

The research being conducted in the area of risk factors, risk behaviors, protective factors, and resiliency points to new directions for future study. According to Rutter (1997), a main topic for future research is to examine the interplay between nature and nurture in development. Thus, future topics include how adolescents’ exposure to adversity is related to parent behaviors, peer behaviors, and other significant individuals’ behaviors and also how that exposure shapes cognitive and emotional development. These topics include the need for longitudinal studies, interdisciplinary research teams, and robust applied research.

There is a strong need for transactional, cross-lagged longitudinal studies that focus on elucidating the developmental processes underlying the protective and risk factors and the dynamic interactions of those factors, as well as the developmental pathways of individuals. These longitudinal studies and normative samples need to incorporate multifactorial designs and large samples (Masten, 1999). This design and methodology will enable an examination of the individual in the context and an investigation of transactional systems simultaneously. Studies would enable investigators to direct their inquiries toward discovering how assets, moderators, and other mechanisms work, that is, how they confer protective or risk characteristics and how these processes change as a function of development. Through examining mediators and moderators, an investigation could provide insight into the degree to which various mechanisms might influence the effects of a specific risk or protective factor or the interaction of those characteristics (Luthar et al., 2000).