Sample Conventions And Norms Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The predominant view of ‘convention’ is that it describes a kind of equilibrium behavior among individuals in a strategic situation, a basic feature of which is the existence of at least one potential alternative equilibrium. A convention is therefore an arbitrary but stable social regularity. ‘Norm’ has several meanings. It can refer to a mere statistical regularity or, in moral theory, a prescriptive rule for human behavior. In the sense pursued here, however, a norm describes a regularity of behavior among a population of individuals, the central feature of which is that most or all of the individuals approve conformity to the regularity and/or disapprove non-conformity. Thus, conventions and norms are distinct but overlapping social regularities.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Introduction

A few (putative) conventions will identify the topic and illustrate its importance. A common example is the regularity of driving on only one side of the road (left or right). Another is monetary currency (see Hume [1740] 1978, p. 490). The convention here is to treat a particular form of metal or paper as having value sufficient to exchange it for goods and services whose value is otherwise (without the convention) far greater. In each case, an individual wishes to follow the regularity once it arises—to avoid the danger of driving into oncoming traffic or the inefficiency of barter. Yet these conventions are arbitrary: everyone driving on the left works like everyone driving on the right; everyone accepting one paper form as currency works much like everyone accepting another.

Language is similarly thought to be conventional because different sounds could be used to refer a given thing, but to communicate successfully, an individual is better off using the sound that others use. One might object to the idea that all of language is a convention if a convention is thought to require a convening, i.e., an actual agreement. An agreement to use certain sounds as language must be expressed in language, so some language must exist prior to any agreement based convention (see Quine [1936] 1967). Lewis (1969) and others have since argued that a convention can occur without any agreement, suggesting that language may indeed be conventional.

Language provides one example of the significance of conventions. A clear understanding of conventions may illuminate a variety of other important social phenomena. Hume ([1740] 1978, pp. 477–513) con-tended that justice, particularly the institution of property, was based on convention (see Vanderschraaf 1998). Some theorists give conventions a central role in the theory of morality or law. Conventions and norms (discussed below) also explain ‘spontaneous order’ that arises without a centralized force such as the state. If so, conventions (or norms) might sustain some forms of cooperation in the ‘state of nature’ and thereby complicate or refute social contract theories that justify the state by the disorder that exists in its absence (see Skyrms 1996, Taylor 1987). Once the state exists, spontaneous order may limit the domains in which state power is necessary (see Ellickson 1991), or contrarily, state action may be necessary to restrict or unsettle undesirable conventions (or norms) (see McAdams 1997, pp. 409–32).

2. Defining ‘Convention’

2.1 Convention As Agreement Or Jointly Accepted Principle Of Action

In one view, a convention is a ‘jointly accepted principle of action’ (Gilbert 1989, p. 377). A principle of action is a rule prescribing (at least presumptively) how to behave in certain situations. An individual can adopt a principle of action unilaterally or jointly. Gilbert (1990, p. 16) gives an example of the latter: A chastises B for failing to adhere to a previous regularity they had observed (about who phones back when they are accidentally disconnected) without prior agreement. B acquiesces in the criticism and apologizes. By this communicative exchange, Gilbert says the parties have created a convention by ‘jointly accepting’ a principle of action requiring behavior they previously engaged in without convention.

Joint acceptance does not, however, explain the common intuition that conventions are in some sense arbitrary. Suppose two individuals face the prospect of a recurrent situation in which neither can survive unless each takes some specific action. On this view, if the individuals jointly accept the only principle of action that will save their lives, the principle is a convention although it is in no sense arbitrary. In addition, Gilbert’s example reveals how close this understanding of convention is to the idea that conventions are agreements. Arguably A and B have implicitly agreed because each believes that A’s criticism impliedly asserted the existence of a mutual obligation and that B’s acquiescence revealed B’s assent to this assertion. The joint acceptance idea clarifies how agreements produce conventions, but not how conventions arise without agreement.

2.2 Conventions As Solutions To Recurrent Coordination Games

Lewis’ Convention (1969) is the origin of an alternative view of convention, one that explicates the way in which they are arbitrary and contends that no explicit or implicit agreement is necessary. Lewis (1969, p. 42) initially modeled conventions as solutions to recurrent coordination games. A game is a situation in which the outcome of any one’s action depends on the decisions of other individuals as well as one’s own. In game theory, players (usually) rationally choose among alternative strategies. Each combination of the players’ strategies produces an outcome, which consists of a utility index for each player.

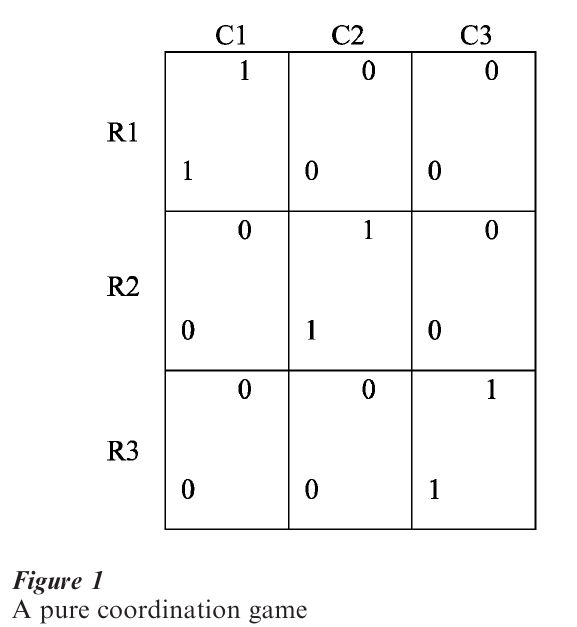

Pure coordination games involve purely common interests among the players. Consider people who want to meet each other but who have failed to communicate in advance where to meet. Lewis (1969, p. 9) uses the matrix in Fig. 1 to describe such a coordination game involving two players and three possible meeting places. One player— ‘R’ for Row-chooser—can play strategies R1, R2, or R3, which consist of going to places P1, P2, or P3, respectively. The other player— ‘C’ for Column-chooser—can play strategies C1, C2, and C3, which consists of going to the same three places, respectively. The players choose their strategies simultaneously, not being able to observe what the other has done. Each receives more utility from meeting (1) than from not meeting (0). (The number in the lower left corner of a cell represents the utility of Row-chooser; the upper right number states the utility of Column-chooser.) Each player therefore has an interest (equal in this example) in coordinating his or her action with that of the other player.

Specifically, R wants to coordinate by playing R1 if C plays C1, R2 if C plays C2, and R3 if C plays C3. C wants to play C1 if R plays R1, C2 if R plays R2, and C3 if R plays R3. Taken together, these observations identify three pure-strategy Nash equilibria, outcomes in which no one player can gain by changing his or her strategy: R1 C1, R2 C2, and R3 C3. For example, R1 is the best response R can make to C1 and that same strategy—C1—is the best response C can make to R1. Thus, given R1 C1, neither player would want to switch strategies unilaterally. The same is true for R2 C2 and R3 C3. (There are also mixed strategy Nash equilibria, as where R and C each go to each of the three places with a probability of one-third.)

This analysis reveals the need for coordinated expectations. Except by accident, players ‘solve’ a coordination game only if they have accurate expectations about what the other(s) will do. In the example, each player needs to expect the other to go to the same place, for example, P1. But if each player knows the other wishes to meet, then, except by accident, it seems that R will expect to meet C at P1 only if R believes that C expects to meet R there as well. But C will expect to meet R at P1 only if C believes that R expects C to go there. Lewis (1969, pp. 52–60) claims the need for common knowledge. Common knowledge of a fact x means that everyone in the relevant population believes x, believes that everyone believes x, believes that everyone believes that everyone believes x, and so on, ad infinitum. Except by accident, coordination seems to require that each player have common knowledge of what the other(s) will do.

Finally, consider how a coordination game can recur. Such a situation would exist if, on repeated occasions, R and C find themselves involuntarily separated in a crowd and in need of a meeting place. More generally, the question of which side of the road to drive on, what paper to use as currency, and what sounds to use to communicate, all arise repeatedly.

A convention may then be provisionally understood as a pure-strategy Nash equilibrium to a recurrent coordination problem. A convention consists of the coordinated expectations that produce the equilibrium and the regularity of behavior the equilibrium represents. Because the situation is a coordination game, the equilibrium is arbitrary in that there is at least one alternative equilibrium.

2.3 Convention As An Arbitrary Equilibrium

In several ways, Lewis’ approach is narrow. First, Lewis (1969, p. 78) requires common knowledge even of the fact that there is an alternative equilibrium. This condition is not necessary to make the regularity stable; knowing the alternative might even make it less stable. The condition thus excludes an arbitrary regularity from being a convention merely because most individuals never discover, or later forget, what the alternative is. On this view, a population’s language would not be conventional if the population were unaware of the possibility of other languages (see Burge 1975).

Moreover, certain aspects of a pure coordination problem seem unnecessary to the definition of convention. Lewis’ final definition (1969, p. 78) generalizes beyond coordination games, but only to overcome a problem in describing the recurrent situation when the behavior is continuous rather than discrete. Lewis retains two significant features of pure coordination games, requiring that (a) ‘almost every-one has approximately the same preferences regarding all possible combinations of actions,’ and (b) ‘almost everyone prefers that any one more conform to [the regularity], on condition that almost everyone con-form to [it].’ The latter point means that most individuals conditionally prefer both their own conformity and the conformity of others. Each requirement excludes regularities that are plausibly conventions.

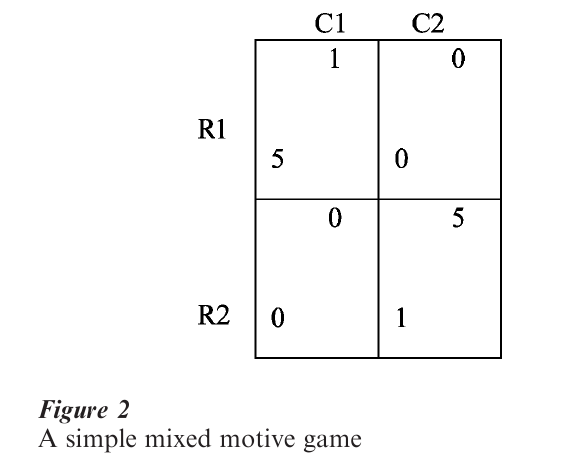

First, there is an element of coordination in many games that also involve conflict. As long as there is some common interest, one may wonder why the equilibrium outcome, when others are possible, is not a convention. For example, in Fig. 2 (sometimes called ‘the battle of the sexes’ based on an early illustration), each player prefers coordinating at Nash equilibria R1/C1 or R2/C2 to either other outcome. But each player also strongly prefers one equilibrium to the other and these preferences conflict. Thus, the players do not have ‘approximately’ the same preferences for outcomes (which they would if we replaced each 5 with, say, 1.05). Lewis would not count a solution to this game as a convention even though it were one of two equilibria and the players each prefer coordinating at an equilibrium than reaching a nonequilibrium outcome.

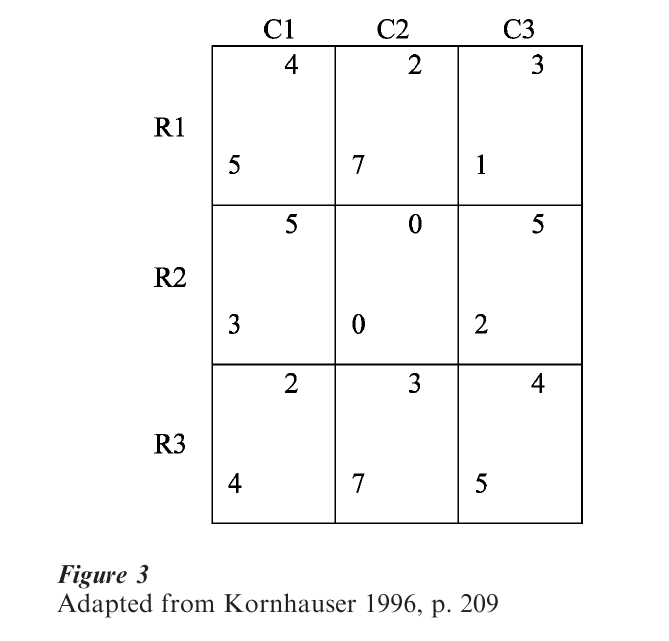

Another weakness in Lewis’ account is his requirement that the players conditionally prefer other players’ conformity even though the stability of a regularity depends only on players preferring their own conformity. With a mix of common and conflicting interests, players may prefer that other players deviate from any of the multiple equilibria. In Fig. 3, R1/C1 and R3/C3 are the only Nash equilibria. As in Fig. 1, the players are indifferent between these equilibria and prefer to coordinate on either than to reach other outcomes that are worse for each (R1/C3, R2/C2, and R3/C1). But unlike Fig. 1, in each of these equilibria, the players do not prefer that the other conform to the equilibrium because each would gain by the other playing a different strategy. At R1/C1, R prefers that C plays C2 and C prefers that R plays R2. The same is true at R3/C3.

Lewis (1969, pp. 45–6) acknowledges the point with this example: suppose those planning to attend a party wish to wear the same style of clothing that others wear. But suppose many ‘nasty’ people prefer that many others fail to conform to the regularity and thereby suffer embarrassment. Because these nasty people do not conditionally prefer that most others conform, Lewis would not consider it a convention even if, based on coordinated expectations, everyone arrives at the party dressed in the same style. The more common intuition is that, regardless of nasty preferences, a stable and arbitrary clothing regularity is a convention (see Miller 1986, p. 123).

These examples suggest dispensing with the requirements that players have approximately the same preferences for all outcomes and conditionally prefer that others conform. A convention may then be broadly defined as the coordinated expectations that sustain a pure-strategy Nash equilibrium, in circumstances where multiple pure-strategy equilibria are possible, and the behavioral regularity that the equilibrium represents. Some would add stability conditions that narrow the definition. Others would expand the equilibrium concept (see Vanderschraaf 1995) and possibly include mixed strategy equilibria where individuals play different pure strategies, each with some probability.

On such a broad view, many more regularities are conventions. For example, in an iterated prisoner dilemma game, there can be multiple equilibria, some of which involve strategies of contingent cooperation. Contingent cooperation can then be conventional even though the players do not have approximately the same preferences for all outcomes. Iterated ‘hawk/ dove’ games may produce conventions even though players do not always prefer others to conform (see Bicchieri 1993, Sudgen 1986). The definition still excludes behavioral regularities (a) that do not arise from situations of strategic interaction (e.g., breathing and sleeping) and (b) that arise in games with only one equilibrium (e.g., a one-shot prisoner’s dilemma).

3. How Conventions Emerge

The simplest way to produce the coordinated expectations necessary for a convention is by agreement. When the parties have sufficiently (not necessarily purely) common interests, there is no need to enforce the agreement. If C and R desire to meet, the agreement to meet at P1 may give each a reason to expect the other to go to P1. Neither has a reason to defect from the agreement. But the game theory account of convention purports to explain their emergence with-out agreement. Some conventions—language and other forms of spontaneous order—seem to require such an origin. How could people form coordinated expectations without agreement?

Much of game theory addresses how players reach equilibrium. The issue is complex and unsettled. It is often quite difficult to demonstrate that players will reach any equilibrium using the common assumption that players are perfectly rational. In a single instance of a coordination game, for example, there is no purely rational basis for expecting a player to select one particular equilibrium outcome. Game theorists believe, however, that players might coordinate on a ‘salient’ equilibrium or, if the game is recurrent, that players’ strategies might evolve to an equilibrium.

Empirical data suggests that people can solve coordination problems without agreement. Schelling (1960, pp. 54–8) experimented with such problems and found that the psychological ‘prominence’ of certain solutions provided the players ‘focal points’ for coordinating. For example, when the game was selecting a single time of day to meet another, most players selected noon; when asked to select the same positive number, two-fifths selected 1; and when asked to pick a meeting spot on a map, most players selected the only unique feature on the map (for similar results, see Mehta et al. 1994). Apparently, people sometimes solve coordination problems by selecting what each believes the other is most likely to perceive as unique. Lewis (1969, pp. 35–6) calls this psychological feature salience. As he observes, what is salient need not be the most desirable, but may even be the least desirable equilibrium (but is still more desirable for each than noncoordination).

The empirical effectiveness of salience seems sufficient to demonstrate that conventions can arise without explicit or implicit agreement. But salience itself is difficult to analyze. Salience does not seem to work by rationality alone. Knowing that one equilibrium strategy ‘sticks out’ from the rest does not justify expecting other players to select it unless one knows that those players favor salient outcomes, which is not required by rationality. Also, rationality alone does not explain what is salient, that is, it does not explain how to select among various dimensions by which to evaluate uniqueness. Similarly, in re-current games, precedent may supply a means of coordinating, but the selection of precedent requires something beyond rationality. Before expectations are coordinated, there is always uncertainty about whether or which past behavior is a precedent for the present behavior. There are many dimensions from which to evaluate whether or which past incident ‘sticks out’ as being like the present one (see Sugden 1998, Gilbert 1989).

For recurrent games, theorists increasingly offer evolutionary accounts to explain the emergence of an equilibrium. The evolution in these models typically does not occur through greater sexual reproduction of players who enjoy greater success in the recurrent game. Rather, evolution occurs by players, often imperfectly rational, learning from experience in the game and switching to strategies that provide greater expected utility. Evaluating the success of these models is beyond the scope of this research paper. Some argue, however, that the same problem of induction that affects salience also infects evolutionary models, to the extent they require players to detect the patterns that constitute a game and other players’ strategies in that game (see Sudgen 1998).

4. Defining ‘Norm’

As noted above, a norm can be a mere behavioral regularity among individuals, as the fact that most people in a population drink coffee or tea nearly every morning. In moral theory, a norm can be a prescriptive rule or reason for action. Thus, one could sensibly assert the existence of a moral norm obligating certain behavior even though no one actually adheres to the norm. In a third sense, a norm is a behavioral regularity but not ‘merely’ one. It is a regularity sustained in part by the fact that individuals generally approve (and otherwise reward) conformity and/or disapprove (and otherwise punish) nonconformity. Norms are, therefore, perceived by individuals in the relevant population as obligatory, a regularity one ‘ought’ to follow, whether or not they are justified in moral theory. This rest of this research paper discusses this third sense of the term.

The definition of norm (in the sense indicated) entails at least three elements (see Pettit 1990). First, it is a behavioral regularity generally followed by the individuals in a population. This requirement distinguishes a society’s mere aspirations for behavior from the norms that its members actually follow. One might want to expand the definition, however, to include cases where most do not follow the regularity but most either follow the regularity or bear significant costs to avoid having their nonconformity discovered. Second, a norm is a regularity in which conformity is approved and/or nonconformity is disapproved. On a broad view, the approval and disapproval need not be morally justified or even based on principle but may include the simple attitudes of being positively or negatively inclined toward—liking or disliking—the behavior. Pettit (1990, p. 731) suggests a third requirement: that the pattern of approval and disapproval ‘helps to ensure’ the existence of the regularity. The causal contribution may be unconscious and contingent, in that other considerations may usually suffice to sustain the regularity but the (dis)approval pattern fills in when those considerations fail.

One may also follow Pettit (1990, p. 751) in requiring some kind of common belief or knowledge of the existence of the above three elements. Even given these elements, if most people were unaware of the regularity, thinking that contrary behavior is equally common, it would seem odd to label the covert regularity a norm. The same might be true if people were aware of the regularity but not of the pattern of (dis)approval, or perhaps even if people were aware of both but attributed the regularity solely to other forces, thinking the pattern to be epiphenomenal. Finally, people might generally believe that all three elements exist, but might make mistakes about what others believed of these facts, or what others believe other believe, and so on. One may require some higher order beliefs, or at least the absence of contrary beliefs, although not necessarily full-scale common knowledge.

Norms may then be distinguished from conventions, which do not require approval of conformity and/or disapproval of nonconformity, but may be sustained entirely by other means. There is substantial room for overlap, but individuals may approve of conformity to behavioral regularities that are not conventions and they may follow conventions without approving others’ conformity or disapproving their nonconformity.

5. The Origin Of Informal Norms

Legal norms are formal; they are promulgated and enforced by the centralized authority of the state. Nongovernmental organizations also formally promulgate and enforce norms. But some norms arise and are enforced informally and without centralized authority. Informal negative sanctions include censure, gossip, ostracism, and violence. Positive sanctions include praise and the provision of social and economic opportunities. Beyond external sanctions, one may approve or disapprove one’s own conformity or nonconformity, respectively, and experience pride or guilt. Informal norms are important because they contribute to spontaneous order, which has implications for, among other things, political theory.

A key question is how informal norms first arise. What causes the behavioral regularity and what causes people to embrace it as obligatory? Some theorists emphasize nonrational forces and, indeed, view norm-based explanations of behavior as an alternative to rational choice explanations. As implied above, norms can be ‘internalized’ so that one feels guilt or anxiety from violating a norm, and pride or self-satisfaction from complying, even if no one else is aware of one’s behavior. Elster (1989, pp. 97–151) emphasizes this emotional feature of norms. He claims that, contrary to rational behavior, a defining characteristic of norm-based action is that it is not ‘outcome-oriented.’ Internalization, however, seems a poor candidate for explaining norm origin. However it occurs, it seems more likely to follow than to precede the approval of conformity and/or disapproval of nonconformity.

By contrast, rational choice theorists have offered two nonexclusive ways of explaining norm origin (see Pettit 1990). They differ by whether one explains the behavioral regularity as arising before or after the pattern of approval and disapproval.

5.1 Deriving Norms From Regularities

The common way to derive a norm from interest is to explain first how a regularity arises and second how people come to approve conformity to the regularity and/or disapprove nonconformity. Game theory addresses the first issue—regularities—by its study of the mechanisms by which equlibrium is achieved. The (dis)approval patterns may subsequently arise for various reasons. Lewis (1969, pp. 97–100), for example, notes that conditions of a convention may easily give rise to approval of conformity. Even if conventions need not include his requirement that most individuals conditionally prefer that others con-form (discussed above), it will often be the case that the condition holds. For example, one driving on the conventional side of the road desires that others follow the convention. In this circumstance, it is easy to imagine that self-interested individuals begin to approve of others conforming to the convention, given the danger they each face from nonconformity. Similarly, if contingent cooperation is a convention in an iterated prisoner’s dilemma game, one will not only expect but also prefer that another engages in the conventional cooperation (see Bicchieri 1993).

A consequence of this analysis is that a regularity might first be a convention, become both a convention and a norm, and end up as a norm only. After the regularity became a norm, it might cease to be arbitrary in the sense described above. The incentives created by the norm—particularly if it is ultimately internalized—might change the payoffs so that the only equilibrium outcome was conformity with the norm regularity.

5.2 Deriving Norms From Patterns Of Approval And Disapproval

A less common means of deriving norms from interest is to explain first how a pattern of approval and disapproval arises and second how this produces a behavioral regularity. Various mechanisms might pro-duce the attitudinal pattern, the most obvious being the egoistic effect just discussed. Despite there being no regularity at this stage, it is easy to imagine that one person disapproves (approves) of another for conduct that harms (benefits) the former. Thus, prior to a regularity, an individual may negatively regard a neighbor who makes loud and disturbing noises and positively regard those who clean up common areas. The same result could occur through moralistic rather than egoistic reasoning, if individuals each tend to disapprove (approve) of behavior they believe generally harms (benefits) others.

These patterns of (dis)approval can create behavioral patterns if individuals sufficiently value esteem, i.e., the approval and good opinion of others, as an end. In some circumstances, individuals may (a) acquire information about the behavior of others without bearing any cost for that purpose, and (b) form an esteem judgment of approval or disapproval, which, being essentially reflexive and involuntary, is also costless. If so, the allocation of esteem creates a costless means of punishing or rewarding others. The desire for approval and the fear of disapproval may cause individuals to conform to a known pattern of esteem judgments (see Pettit 1990, McAdams 1997).

Elster (1989, p. 133) observes that expressing dis-approval is always costly, as it takes time and risks the retaliation of the target. One might add that selectively expressing approval risks retaliation by those not approved. But these costs need not prevent esteem-judgments from operating as a sanction and producing a norm. First, judgments of disapproval need not be expressed to be perceived. Introspection may suffice: if A hates having her sleep disturbed by a loud noise, she may simply guess that others will disapprove of her for waking them with a loud noise (see Pettit 1990, p. 740). Second, there may be a cost to concealing one’s esteem judgment that offsets the costs of expression. Suppose B prefers to socialize only with people he esteems. For B, inviting to a social gathering people he does not esteem (or forgoing the gathering altogether) is more costly than revealing his negative esteem judgments. B therefore rationally invites only those whom he esteems and, despite the costs, indirectly expresses his negative judgments about others. As to both points, if individuals value esteem, they will seek evidence of how to get it, so even a trivial clue may cause people to form beliefs about the judgments being made. Once individuals perceive a pattern of approval and disapproval, they may gain (net) approval by directly expressing views consistent with the pattern.

Because individuals will tend to approve commonly beneficial behavior more than commonly harmful behavior, the discussion implies that norms derived from (dis)approval patterns will tend to be socially beneficial. A more detailed analysis would reveal several offsetting effects. However norms are derived, they can cause harm in a variety of ways, particularly by allowing one group to benefit itself at the expense another (see Hardin 1995, Ullman-Margalit 1977, pp. 134–97).

Bibliography:

- Bicchieri C 1993 Rationality and Coordination. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Burge T 1975 On knowledge and convention. Philosophical Review 84: 249–55

- Ellickson R C 1991 Order Without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Elster J 1989 The Cement of Society: A Study of Social Order. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Gilbert M 1989 On Social Facts. Routledge, London

- Gilbert M 1990 Rationality, coordination, and convention. Synthese 84: 1–21

- Hardin R 1995 One for All: The Logic of Group Conflict. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Hume D [1740] 1978 A Treatise of Human Nature. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Kornhauser L A 1996 Conceptions of social rule. In: Draybrooke D (ed.) Social Rules: Origin; Character; Logic; Change. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Lewis D K 1969 Convention: A Philosophical Study. Harvard, University Press, Cambridge, MA

- McAdams R H 1997 The origin, development, and regulations of norms. Michigan Law Review 96: 338–433

- Mehta J, Starmer C, Sugden R 1994 The nature of salience: An experimental investigation of pure coordination game. American Economics Review 84: 658–73

- Miller S R 1986 Conventions, interdependence of action, and collective ends. Nous 20: 177–40

- Pettit P 1990 Virtus Normativa: rational choice perspectives. Ethics 100: 725–55

- Quine W V 1967 [1936] Truth by convention. In: Lee O H (ed.) Philosophical Essays for Alfred North Whitehead. Russel & Russel, New York

- Schelling T C 1960 The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Skryms B 1996 Evolution of the Social Contract. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Sugden R 1986 The Economics of Rights, Co-operation and Welfare. B. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Sugden R 1998 The role of inductive reasoning in the evolution of conventions. Law and Philosophy 17: 377–410

- Taylor M 1987 The Possibility of Cooperation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Ullmann-Margalit E 1977 The Emergence of Norms. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Vanderschraaf P 1995 Convention as correlated equilibrium. Erkenntnis 42(1): 65–87

- Vanderschraaf P 1998 The informal game theory in Hume’s account of convention. Economy and Philosophy 14: 215–47