This sample juvenile delinquency research paper features: 6300 words (approx. 21 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 76 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Outline

- Introduction

- Origins of the Study of Juvenile Delinquency

- Juveniles Placed in Institutions

- Creation of the Juvenile Court

- Influence of Positivism

- The Emergence of Sociological Theory

- Environmental Influences on Juvenile Delinquency

- The Family

- The School

- Peers and Gangs

- The Use of Drugs and Its Relationship to Delinquent Behavior

- The Biological, Psychological, and Sociological Theories

- Biological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

- Psychological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

- Sociological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

- Is Delinquent Behavior Rational?

- Conclusion and Prospects for the 21st Century

- Developmental Paths of Delinquency

- Human Agency and Delinquency across the Life Course

- Gender and Delinquent Behavior

- Delinquency Prevention

- Bibliography

Introduction

Juvenile delinquency—crimes committed by young people—constitute, by recent estimates, nearly one fifth of the crimes against people and one-third of the property crimes in the United States. The high incidence of juvenile crime makes the study of juvenile delinquency vital to an understanding of American society. The Uniform Crime Reports, juvenile court statistics, cohort studies, self-report studies, and victimization surveys are the major sources of data used to measure the extent and nature of delinquent behavior. These forms of examination have generally agreed on the following findings:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

- Juvenile delinquency is widespread in the United States.

- The majority of youths have committed some form of delinquency during their adolescent years.

- Three out of four juvenile arrests are arrests of males.

- Lower-class youths tend to commit more frequent and serious offenses than do higher-class youths.

- Minority youths, especially African American, tend to commit more serious delinquent acts than do white youths.

The number of juvenile homicides has been going down since the mid-1990s. Philip J. Cook and John Laub (1998) found that a changing context, as well as a more limited availability of guns, helped explain the reduced rate of juvenile homicides. Cook and Laub predicted that this changing context would continue to decrease youth homicides in the immediate future. Cook and Jens Ludwig (2004) and Anthony A. Braga (2003) also identified the high correlation between gun ownership and juvenile homicides.

The study of juvenile delinquency is full of conflicting positions. There are those who believe that this area of study should be limited to the theories of why juveniles become involved with crime. Others contend that the study of delinquency also ought to include the environmental influences on juvenile crime, such as the family, school, peer and gang participation, and drug involvements. Still others conclude that the study of delinquency should include the social control of juvenile crime, as well as causation theories and environmental influences.

The study of delinquency has clearly changed over the years. Throughout the twentieth century, delinquency studies became more interdisciplinary, more concerned about the integration with other theories, more methodologically sophisticated, and more focused on long-term follow-up of juveniles, sometimes for several decades. The importance of human agency and delinquency across the life course, both of which rose in theoretical importance during the 1990s, are generating considerable excitement in the early years of the twenty-first century.

The main concerns of this research paper are the origins of the study of delinquency; the emergence of sociological theory; the environmental influences on delinquency; the biological, psychological, and sociological theories that have influenced the field of delinquency; the interdisciplinary theories that are affecting the study of juvenile delinquency; and the prospects for future developments.

Origins of the Study of Juvenile Delinquency

What to do with wayward juveniles has long been a concern of American society. Before the end of the eighteenth century, the family was believed to be the source of cause of deviancy, and therefore, the idea emerged that perhaps the well-adjusted family could provide the model for a correctional institution for children. The house of refuge, the first juvenile institution, reflected the family model wholeheartedly; it was designed to bring the order, discipline, and care of the family into institutional life. The institution was to become the home, the peers, the siblings, the staff, and the parents (Rothman 1971).

Juveniles Placed in Institutions

The New York House of Refuge, which opened on January 1, 1825, with six girls and three boys, is generally acknowledged as the first house of refuge. Over the next decade, Bangor, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Mobile, Philadelphia, and Richmond followed suit in establishing houses of refuge. Twenty-three schools were chartered in the 1830s and another 30 in the 1840s. Some houses of refuge were established by private agencies, some by state governments or legislatures, and some jointly by public authorities and private organizations (Rothman 1971).

One of the changes in juvenile institutions throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century was the development of the cottage system. Eventually called “training schools” or “industrial schools,” these institutions would house smaller groups of youths in separate buildings, usually no more than 20–40 youths per cottage. House parents, typically a man and his wife, constituted the staff in these cottages. Early cottages were log cabins; later cottages were constructed from brick or stone.

Barbara M. Brenzel’s (1983) study of the State Industrial School for Girls in Lancaster, Massachusetts, the first state reform school for girls in the United States, revealed the growing disillusionment in the mid- to late nineteenth century regarding training schools. Intended as a model reform effort, Lancaster was the first “familystyle” institution in the United States and embodied new theories about the reformation of youths. However, an “examination of a reform institution during the second half of the nineteenth century reveals the evolution from reformist visions and optimistic goals at mid-century to pessimism and ‘scientific’ determinism at the century’s close” (p. 1). Brenzel added that “the mid-century ideal of rehabilitative care changed to the principle of rigid training and custodial care by the 1880s and remained so into the early twentieth century” (pp. 4–5).

Creation of the Juvenile Court

During the final decades of the nineteenth century, the Progressive Reformers viewed childhood as a period of dependency and exclusion from the adult world. To institutionalize childhood, they enacted a number of “child saving” laws, including child labor and compulsory school attendance laws. The juvenile court was viewed as another means to achieve unparalleled age segregation of children (Feld 1999). The following are a number of contextual factors that influenced the creation of this court.

Legal Context

The juvenile court was founded in Cook County (Chicago), Illinois, in 1899, when the Illinois legislature passed the Juvenile Court Act, and later that year was established in Denver, Colorado. The parens patriae doctrine provided a legal catalyst for the creation of the juvenile court, furnishing a rationale for use of informal procedures for dealing with juveniles and for expanding state power over the lives of children.

Political Context

In the Child Savers,Anthony Platt (1977) developed the political context of the origin of the juvenile court. He stated that the juvenile court was established in Chicago and later elsewhere because it satisfied several middleclass interest groups. He saw the juvenile court as an expression of middle-class values and of the philosophy of conservative political groups. In denying that the juvenile court was revolutionary, Platt charged that

the child-saving movement was not so much a break with the past as an affirmation of faith in traditional institutions. . . . What seemingly began as a movement to humanize the lives of adolescents soon developed into a program of moral absolutism through which youths were to be saved from movies, pornography, cigarettes, alcohol, and anything else which might possibly rob them of their innocence. (Pp. 98–99)

Economic Context

Platt (1977) argued that the behaviors that the child savers selected to be penalized—such as roaming the streets, drinking, fighting, engaging in sex, frequenting dance halls, and staying out late at night—were found primarily among lower-class children. Accordingly, juvenile justice from it inception, he contended, reflected class favoritism that resulted in the frequent processing of poor children through the system while middle- and upper-class children were more likely to be excused.

Sociocultural Context

The social conditions that were present during the final decades of the nineteenth century were the catalysts that led to the founding of the juvenile court. One social condition was that citizens became increasingly incensed by the treatment of children, especially the policy of jailing children with adults. Another social condition was that the higher status given middle-class women made them interested in exerting their newfound influence to improve the lives of children (Faust and Brantingham 1974).

Influence of Positivism

These pressures for social change took place in the midst of a wave of optimism that swept through the United States during the Progressive Era, the period from 1899 to 1920. The emerging social sciences assured reformers that their problems with delinquents could be solved through positivism. According to positivism, youths were not responsible for their behavior and required treatment rather than punishment.

The concept of the juvenile court spread rapidly across the United States; by 1928, only two states did not have a juvenile court statute. In Cook County, the amendments that followed the original act brought the neglected, the dependent, and the delinquent together under one roof. The “delinquent” category comprised both status offenders and actual violators of criminal law.

Urban juveniles courts, especially, had clinics that provided psychological services for those youths referred to them by the juvenile court. Those who provided such services in the clinics were psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, or psychiatric social workers. The treatment modality that was frequently used was various versions of Freudian psychoanalysis. Typically, in a one-to-one relationship with a therapist, youths in trouble were encouraged to talk about past conflicts that caused them to express emotional problems through aggressive or antisocial behavior. The insights that youths gained from this psychotherapy were intended to help them resolve the conflicts and unconscious needs that drove them to crime. As a final step of psychotherapy, youths would become responsible for their behaviors.

The Emergence of Sociological Theory

From the second decade of the twentieth century, the Chicago School of Sociology developed a sociological approach to delinquency that differed greatly from that found in psychological positivism. The intellectual movement of social disorganization theory came out of this Chicago school. To William I. Thomas and Florian Znaniecki (1927), social disorganization reflected the influence of an urban, industrial setting on the ability of immigrant subcultures, particularly parents, to socialize and effectively control their children. S. P. Breckinridge and Edith Abbott (1970) contributed the idea of plotting “delinquency maps.” Frederick M. Thrasher (1927) viewed the youth gang as a substitute socializing institution whose function was to provide order, or social organization where there was none, or social disorganization.

Clifford R. Shaw and Henry D. McKay extended social disorganization by focusing specifically on the social characteristics of the community as a cause of delinquency. Their pioneering investigations established that delinquency varied in inverse proportion to the distance from the center of the city, that it varied inversely with socioeconomic status, and that delinquency rates in a residential area persisted regardless of changes in racial and ethic composition of the area (Reiss 1976).

Shaw and McKay viewed juvenile delinquency as resulting from the breakdown of social control among the traditional primary groups, such as the family and the neighborhood, because of the social disorganization of the community. Urbanization, rapid industrialization, and immigration processes contributed to the disorganization of the community. Thus, delinquent behavior became an alternative mode of socialization through which youths who grew up in disorganized communities were attracted to deviant lifestyles (Finestone 1976).

Shaw and McKay turned to ecology to show this relationship between social disorganization and delinquency. Shaw (1929) reported that marked variations of school truancy, juvenile delinquency, and adult criminality existed among different areas in Chicago. Shaw found that the nearer a given locality was to the center of the city, the higher its rates of delinquency and crime. Shaw further found that areas of concentrated crime maintained their high rates over a long period, even when the composition of the population changed markedly. Shaw and McKay (1931), in a study performed for the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, reported that this basic ecological finding was also true for a number of other cities.

In their classic work Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas, Shaw and McKay (1942) developed these ecological insights in greater scope and depth. They studied males who were brought into the Cook County juvenile court on delinquency charges in 1900–1906, 1917–1923, and 1927–1933. Over this 33-year period, they discovered that the vast majority of the delinquent boys came from either an area adjacent to the central business and industrial areas or along two forks of the Chicago River. Then, applying Burgess’s concentric zone hypothesis of urban growth, they measured delinquency rates by zone and by areas within the zone. They found that in all three periods, the highest rates of delinquency were in Zone I (the central city), the next highest in Zone II (next to the central city), in progressive steps outward to the lowest in Zone V. Significantly, although the delinquency rates changed from one period to the next, the relationship among the different zones remained constant, even though in some neighborhoods the ethnic compositions of the population changed totally.

Shaw and McKay eventually refocused their analysis from the influence of social disorganization of the community to the importance of economics on high rates of delinquency. They found that the economic and occupational structure of the larger society was more influential in the rise of delinquent behavior than was the social life of the local community. They concluded that the reason members of lower-class groups remained in the inner-city community was less a reflection of their newness of arrival and their lack of acculturation to American institutions than it was a function of their class position in society (Finestone 1976).

Environmental Influences on Juvenile Delinquency

The importance of the Shaw and McKay tradition of the environment and community has long remained in the study of delinquency. An examination of the relationship between the family and delinquency, school performance and delinquency, drug use and delinquency, and participation in gangs and delinquency are generally found in studies of environmental influences on delinquency.

The Family

In the midst of conflicting findings about the relationship between delinquency and the family, the following observations have received wide support:

- Family conflict and poor marital adjustment are more likely to lead to delinquency than the structural breakup of the family (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber 1986).

- Children who have delinquent siblings or criminal parents seem to be more prone to delinquent behavior than those who do not (Lauritsen 1993).

- Rejected children appear to be more prone to delinquent behavior than those who have not been rejected. Children who have experienced severe rejection are more likely to become involved in delinquent behavior than those who have experienced a lesser degree of rejection (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber 1986).

- Consistency of discipline within the family appears to be important in deterring delinquent behavior (McCord, McCord, and Zola 1959).

- The rate of delinquency seems to increase with the number of unfavorable factors in the home. Thus, multiple handicaps within the family are associated with a higher probability of juvenile delinquency than are single handicaps (Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber 1986).

The School

Studies have found that the school is a critical context, or arena, of learning delinquent behavior. For example, Eugene Maguin and Rolf Loeber’s (1996) meta-analysis found that “children with lower academic performance offended more frequently, committed more serious and violent offenses, and persisted in their offending” (p. 15).

The extent of delinquency in the school, including vandalism, violence, gangs, and the use of drugs, has received considerable examination (Bartollas 2006). The consequences of dropping out of school have also been investigated (Jarjoura 1993). In addition, there have been a number of efforts to improve the quality of the school experience. The development of alternative schools, the process of designing effective school-based violenceprevention programs, and the process of developing more positive school-community relationships have been three of the most promising intervention strategies in the school setting (Bartollas 2006).

Peers and Gangs

Researchers usually agree that most delinquent behavior, particularly more violent forms, takes place in groups, but they disagree on the quality of relationships within delinquent groups and on the influence of groups on delinquent behavior (Breckinridge and Abbott 1970; Piper 1985). There is still debate on several theoretical questions about groups and delinquency: How do delinquent peers influence each other? What causes the initial attraction to delinquent groups? What do delinquents receive from these friendships that result in continuing them?

Youth gangs represent one of the most serious forms of delinquency groups. Frederick Thrasher’s (1927) definition of gangs is still one of the best definitions:

A gang is an interstitial group originally formed spontaneously and then integrated through conflict. It is characterized by the following types of behavior: meeting face to face, milling, movement through space as a unit, conflict and planning. The result of this collective behavior is the development of tradition, unreflective, internal structure, esprit de corps, solidarity, morale, group awareness, and attachment to local territory. (P. 57)

Juveniles are involved in urban street gangs, where they are typically a minority of the membership. However, they make up nearly the total membership of emerging gangs that spread across the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s. What has received considerable documentation is that law-violating behaviors increase with gang activities, that core members are involved in more serious delinquent acts than are fringe members, and that gang activities contribute to a pattern of violent behavior (Wolfgang, Thornberry, and Figlio 1987; Battin-Pearson et al. 1998; Miller 2001; Miller and Decker 2001).

The Use of Drugs and Its Relationship to Delinquent Behavior

Drug and alcohol use and juvenile delinquency have been identified as the most serious problem behaviors of juveniles. The good news is that substance abuse among adolescents has dropped significantly since the late 1970s. The bad news is that drug use has significantly increased among high-risk youths and is becoming commonly linked to juvenile delinquency (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004; Johnston et al. 2004). In addition, more adolescents are selling drugs than ever before in the history of this nation. Moreover, the spread of AIDS within populations of drug users and their sex partners promises to make the problem of substance abuse even more difficult to control.

The Biological, Psychological, and Sociological Theories

A number of theoretical answers have been given to the continually raised question: Why do juveniles commit crime? Early in the twentieth century, biological and psychological causes of delinquent behavior received more attention. In the last two-thirds of the twentieth century, sociological explanations to delinquency behavior received greater support with students of delinquency.

Biological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

The belief in a biological explanation for criminality has a long history. Early approaches attempted to pinpoint the source of criminality in physical anomalities (Lombroso-Ferrero 1972), genealogical deficiencies (Shah and Roth 1974), and theories of human somatotypes or body types (Glueck and Glueck 1956; Cortes 1972). More recently, research has stressed the interaction between the biological factors within an individual and the influence of the particular environment. Supporters of this form of biological positivism claim that what produces delinquent behavior, like other behaviors, is a combination of genetic traits and social conditions. Recent advances in experimental behavior genetics, human population genetics, knowledge of the biochemistry of the nervous system, experimental and clinical endocrinology and neurophysiology, and other related areas have led to more sophisticated knowledge of the way in which the environment and human genetics interact to affect the growth, development, and functioning of the human organism (Shah and Roth 1974; Fishbein 1990).

Psychological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

Psychological factors have long been popular in the positivist approach to the cause of juvenile delinquency because the very nature of parens patriae philosophy requires treatment of youths who are involved in various forms of delinquency. Psychoanalytic (Freudian) theory was first used with delinquents, but more recently other behavioral and humanistic schools of psychology have been applied to the problem of the illegal behaviors of juveniles. For example, some researchers in the 1980s and 1990s addressed the relationship between sensation seeking and crime (White, Labouvie, and Bates 1985; Fishbein 1990). Jack Katz’s (1988) Seductions of Crime conjectures that when individuals commit crime, they become involved in “an emotional process—seductions and compulsions that have special dynamics” (p. 9). It is this “magical” and “transformative” experience that makes crime “sensible,” even “sensually compelling.” James Q. Wilson and Richard Herrnstein’s (1985) Crime and Human Nature is another example of the influence of psychological factors on criminal or delinquent behaviors. They consider potential causes of crime and noncrime within the context of reinforcement theory, that is, the theory that behavior is governed by its consequent rewards and punishments, as reflected in the history of the individual. The rewards of crime, according to Wilson and Herrnstein (1985), are found in the form of material gain, revenge against an enemy, peer approval, and sexual gratification. The consequences of crime include pangs of conscience, disapproval of peers, revenge by the victim, and, most important, the possibility of punishment.

Sociological Explanations of Delinquent Behavior

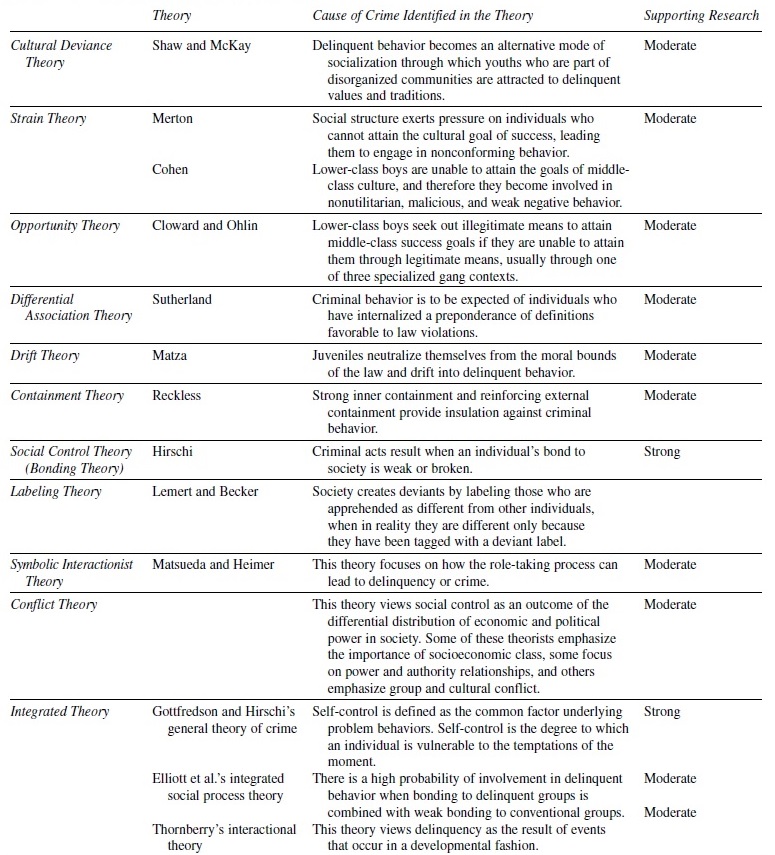

Sociological theories related to delinquency causation have been grouped in a number of ways; the following sections will group them in structural theories of delinquency causation, process theories of delinquency causation, reaction theories of delinquency causation, and integrated theories of delinquency causation.

Structural Theories of Delinquency Causation

The setting for delinquency, as proposed by social structural theories, is the social and cultural environment in which juveniles grow up or the subcultural groups in which they choose to become involved. Using official statistics as their guide, these analysts claim that such forces as social disorganization, cultural deviance, status frustration, and social mobility are so powerful that they induce youths, especially lower-class ones, to become involved in delinquent behavior. Strain theory is a structural theory that has been widely applied to explaining delinquent behavior. Robert K. Merton’s theory of anomie, Albert K. Cohen’s theory of delinquent subcultures, and Richard A. Cloward and Lloyd E. Ohlin’s opportunity theory are the most widely cited strain theories. Merton (1957) examined how deviant behavior is produced by different social structures. His primary aim was to discover how some social structures exerted pressure upon individuals in the society to engage in nonconforming rather than conforming behavior. Cohen’s (1955) thesis in his book Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang was that lower-class youths are actually protesting against the goals of middle-class culture, but they experience status frustration, or strain, because they are unable to attain these goals. Cloward and Ohlin (1960) conceptualized success and status as separate strivings that can operate independently of each other. They portrayed delinquents who seek an increase in status as striving for membership in the middle class, whereas other delinquent youths try to improve their economic post without changing their class position.

Social Process Theories of Delinquency Causation

Social process theories of delinquency causation examine the interactions between individuals and the environment that influence them to become involved in delinquent behaviors. Differential association, drift, and social control theories became popular in the 1960s because they provided a theoretical mechanism for the translation of environmental factors into individual motivation. Edwin H. Sutherland’s (1947) formulation of differential association theory proposes that delinquents learn crime from others. His basic premise was that delinquency, like any other form of behavior, is a product of social interaction. In developing the theory of differential association, Sutherland contended that individuals are constantly being changed as they take on the expectations and points of view of the people with whom they interact in small, intimate groups. The process of becoming a delinquent, David Matza (1964) says, begins when an adolescent neutralizes himself or herself from the moral bounds of the law and drifts into delinquency. Drift, according to Matza, means that “the delinquent transiently exists in limbo between convention and crime, responding in turn to the demands of each, flirting now with one, now the other, but postponing commitment, evading decision. Thus he drifts between criminal and conventional action” (p. 28). Walter C. Reckless’s (1961) control theory is based on the assumption that strong inner containment and reinforcing external containment provide insulation against deviant behavior. Travis Hirschi’s (1967) Causes of Delinquency linked delinquent behavior to the quality of the bond an individual maintains with society, stating that “delinquent acts result when an individual’s bond to society is weak or broken” (p. 16). He argues that humans’ basic impulses motivate them to become involved in crime and delinquency unless there is reason for them to refrain from such behavior.

Social Reaction Theories of Delinquency Causation

Labeling theory, symbolic interactionst theory of delinquency, and conflict theory can be viewed as social reaction theories of delinquency causation because they focus on the role that social and economic groups and institutions have in producing delinquent behavior. The labeling perspective, whose peak of popularity was in the 1960s and 1970s, is based on the premise that society creates deviance by labeling those who are different from other individuals, when in fact they are different merely because they have been tagged with a deviant label part played by social audiences and their responses to the norm violations of juveniles (Tannenbaum 1938; Lemert 1951; Becker 1963; Triplett and Jarjoura 1994). Ross L. Matsueda (1992) and Karen Heimer (1995) have developed a symbolic interactionist theory of delinquency. This interactionist perspective “presupposes that the social order is the product of an ongoing process of social interaction and communication” (Matsueda 1992:1580). What is “of central importance is the process by which shared meanings, behavioral expectations, and reflected appraisals are built up in interaction and applied to behavior” (p. 1580). The conflict perspective views social control as an outcome of the differential distribution of economic and political power in society; thus, laws are seen as creation by the powerful for their own benefit (Shichor 1980). Conflict criminology has a great deal of variation; some theories emphasize the importance of socioeconomic class, some focus primarily on power and authority relationships, and others emphasize group and cultural conflict.

Integrated Theory

The theoretical development of integrated explanations of delinquency in the 1980s and 1990s has made a significant contribution to the understanding of delinquent behavior. Theory integration usually implies the combination of two or more existing theories on the basis of their perceived commonalities. Three of the better-known integrated theories are Michael R. Gottfredson and Travis Hirschi’s (1990) general theory of crime; Delbert S. Elliot, Suzanne A. Ageton, and Rachelle J. Canter’s (1979) integrated social process theory; and Terence P. Thornberry’s (1987) interactional theory.

In A General Theory of Crime, Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) define lack of self-control as the common factor underlying problem behaviors. Thus, self-control is the degree to which an individual is “vulnerable to the temptations of the moment.” The other pivotal construct in this theory of crime is crime opportunity, which is a function of the structural or situational circumstances encountered by the individuals (Grasmick et al. 1993).

Elliott et al. (1979) offer “an explanatory model that expands and synthesizes traditional strain, social control, and social learning perspectives into a single paradigm that accounts for delinquent behavior and drug use” (p. 11). They argue that all three theories are flawed in explaining delinquent behavior. Integrating the strongest features of these theories into a single theoretical model, Elliott and colleagues theorize that there is a high probability of involvement in delinquent behavior when bonding to delinquent groups is combined with weak bonding to conventional groups. In Thornberry’s interaction theory of delinquency, the initial impetus toward delinquency comes from a weaning of the person’s bond to conventional society, represented by attachment to parents, commitment to school, and belief in conventional values. Associations with delinquent peers and delinquent values make up the social settling in which delinquency, especially prolonged serious delinquency, is learned and reinforced. These two variables, along with delinquent behavior itself, form a mutually reinforcing casual loop that leads toward increasing delinquency involvement over time (Thornberry 1987, 1989; Thornberry et al. 2003) (Table 1).

Table 1

Is Delinquent Behavior Rational?

In the 1970s and 1980s, a variety of academic areas, including the sociology of deviance, criminology, economics, and cognitive psychology, began to view crime as the outcome of rational choices and decisions. The ecological tradition in criminology and the economic theory of markets, especially, have applied the notion of rational choice to crime.

Rational choice theory, borrowed primarily from the utility model in economics, was one area of intense interest during the 1980s and 1990s, especially within criminology, sociology, political science, and law. Rational choice theory, an extension of the deterrence doctrine of the classical school, includes incentives as well as deterrents and focuses on the calculation of payoffs and costs before delinquent and criminal acts are committed (Cornish and Clarke 1986; Akers 1990).

An analysis of delinquent behavior leads to the conclusion that antisocial behavior often appears rational and purposeful. Some delinquents clearly engage in delinquent behavior because of the low cost or risk of such behavior. The low risk comes from the parens patriae philosophy that is based on the presumption of innocence for the very young, as well as of reduced responsibility for those up to their midadolescence. Thus, in early adolescence, the potential costs of all but the most serious forms of delinquent behavior are relatively slight.

Conclusion and Prospects for the 21st Century

The development of both sociology and juvenile delinquency was influenced by the rise of the Chicago School of Sociology early in the twentieth century. With this common background, it is not surprising that juvenile delinquency has been so closely related to the discipline of sociology. Juvenile delinquency has been taught in the majority of sociology departments, as well as in many criminology or criminal justice programs in university settings and community colleges. The study of juvenile delinquency is further indebted to sociology because so many of the theories of delinquency causation are sociological theories of crime. Even though the study of juvenile delinquency has become interdisciplinary, sociological principles and theories remain critical in understanding the field of delinquency. Indeed, the new trends in delinquency, such as human agency and delinquency across the life course, are adapted from theoretical and empirical contributions largely taken from the field of sociology.

The prospects for the study of delinquency in the twenty-first century are vibrant and exciting.

Some of the emphases that will guide the study of delinquency are the examination of the development paths of delinquent behavior, a continued examination of human agency and delinquency across the life course, an investigation of the ways in which gender affects the study of delinquency, and a renewed search for more effective means of delinquency prevention.

Developmental Paths of Delinquency

One of the most exciting aspects about the study of juvenile delinquency today is the increasing number of developmental studies that have followed youth cohorts for a few years or even decades. One of the most widely respected of these studies is the research done by Terrie E. Moffitt and colleagues. For example, Moffitt, Donald R. Lynam, and Phil A. Silva’s (1994) examination of the neuropsychological status of several hundred New Zealand males between the ages of 13 and 18 found that poor neuropsychological scores “were associated with early onset of delinquency” but were “unrelated to delinquency that began in adolescence” (p. 277). Moffitt’s (1993) developmental theory views delinquency as proceeding along two developmental paths. On one path, children develop a lifelong path of delinquency and crime as early as age 3. They may begin to bite and hit shoplift and be truant at age 10, sell drugs and steal cars at age 16, rob and rape at age 22, and commit fraud and child abuse at age 30. These “life-course-persistent” (LCP) delinquents, according to Moffitt, continue their illegal acts throughout the conditions and situations they face. During childhood, they may also exhibit such neuropsychological problems as deficit disorders or hyperactivity and learning problems in schools.

On the other path, the majority of delinquents begin offending during the adolescent years and desist from delinquent behaviors around the 18th birthday. Moffitt refers to these youthful offenders as “adolescent-limited” (AL) delinquents. The early and persistent problems found with members of the LCP group are not found with the AL delinquents. Yet the frequency of offending and even the violence of offending during the adolescent years may be as high as the LCP. Moffitt notes that the AL antisocial behavior is learned from peers and sustained through peerbased rewards and reinforcements. AL delinquents continue in delinquent acts as long as such behaviors appear profitable or rewarding to them, but they have the ability to abandon those behaviors when prosocial styles become more rewarding (Moffitt 1993; Moffitt et al. 2001).

Human Agency and Delinquency across the Life Course

This enormous database of these developmental studies has contributed to the examination of such subjects as the importance of human agency in the lives of youths and later when they become adults and to delinquency or crime across the life course. Human agency refers to the importance given to juveniles who are not only acted upon by social influence and structural constraints but who make choices and decisions based on the alternatives that they see before them. Symbolic interactionism and life history studies have long acknowledged the importance of agency and rationality, and rational choice and routine activities research have more recently placed an importance on rationality in delinquent and criminal behavior. However, it has been the increased attention given to the life course in both sociology and delinquency studies that has sparked a dramatic resurgence of interest in agency in contemporary research.

The various perspectives on the life course relate individuals to their broader social context, but within the constraints of their world, individuals make choices among options that are available to them. It is these decisions that are so important in constructing their life course. Delinquency across the life course has been examined extensively by Robert J. Sampson and James H. Laub’s reanalysis of the Gluecks’ data (Sampson and Laub 1993; Laub and Sampson 2003). This perspective of delinquency and crime across the life course has been employed in studies of the effects of youth gangs, faulty family relationships, poor performance in school, drug use, and gender variations in youth offending (Bartollas 2006).

Moreover, this interactive process develops over the person’s life cycle. During early adolescence, the family is the most influential factor in bonding the youngster to conventional society and reducing delinquency. But as the youth matures and moves through middle adolescence, the world of friends, school, and youth culture becomes the dominant influence over behavior. Finally, as the person enters adulthood, commitment to conventional activities, and to family, especially, offers new avenues to reshape the person’s bond to society and involvement with delinquent behavior (Thornberry 1987; Krohn et al. 2001).

Gender and Delinquent Behavior

The study of delinquency has been traditionally shaped by male experiences and understanding of the social world (Daly and Chesney-Lind 1988). Carol Smart (1976) and Dorie Klein (1995) were two early criminologists to suggest that a feminist criminology should be formulated because of the neglect of the feminist perspective in classical delinquency theory. Feminist criminologists have been quick to agree that adolescent females have different experiences compared with adolescent males. They generally support that females are more controlled than males, enjoy more social support, are less disposed to crime, and have fewer opportunities for certain types of crimes (Mazerolle 1998).

However, feminist criminologists disagree on how the male-oriented approach to delinquency should be handled. One approach focuses on the question of generalizability. In research on samples that include males and females, a routine strategy for those who emphasize cross-gender similarities is to test whether the given theoretical constructs account for the offending of both groups and to pay little attention to how gender itself might intersect with other factors to create different meanings in the lives of males and females. Those who support this gender-neutral position have generally examined such subjects as the family, social bonding, social learning, delinquent peer relationships, and, to a lesser degree, deterrence and strain (Daly 1995).

In contrast, other feminist theorists argue that new theoretical efforts are needed to help us understand female delinquency and women’s involvement in adult crime. Eileen Leonard (1995), for example, questioned whether anomie, differential association, labeling, and Marist theories can be used to explain the crime patterns of women. She concluded that these traditional theories do not work for explaining female offending. Meda ChesneyLind’s (1989, 1995) application of the male-oriented theories to female delinquency has argued that existing delinquency theories are inadequate to explain female delinquency. She suggested that there is a need for a feminist model of delinquency, because a patriarchal context has shaped the explanations and handling of female delinquents and status offenders. What this means is that adolescent females’ sexual and physical victimizations at home and the relationship between these experiences and their crimes have been systematically ignored.

Delinquency Prevention

Delinquency prevention has a long but somewhat disappointing history. The best-known models of delinquency prevention have included the Boston’s Mid-city Project, Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study in Massachusetts, Chicago Area Projects, La Playa de Ponce in Puerto Rico, New York City Youth Board, and Walter C. Reckless and Simon Dinitz’s self-concept studies in Columbus, Ohio. A number of studies have examined the effectiveness of these delinquency-prevention programs and have generally found that few studies showed significant results (Lundman, McFarlane, and Scarpitti 1976; Lundman and Scarpitti 1978).

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing to the present, a number of new delinquency-prevention efforts have been established. The Blueprints for Violence Prevention, developed by the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado–Boulder and supported by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, identified 11 model programs, as well as a number of promising violence-prevention and drug abuse programs. The identified model programs were Big Brothers Big Sisters of America; Bully Prevention Program; Functional Family Therapy (FFT); Incredible Years: Parent, Teacher, and Child Training Series; Life Skills Training; Midwestern Prevention Project; Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC); Multisystemic Therapy (MST); Nurse-Family Partnership; Project Towards No Drug Abuse; and Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (Mihalic et al. 2004).

The popularity of delinquency-prevention programs, of course, is found in the realization that the most desirable strategy is to prevent delinquent behavior before it can occur. Even though delinquency-prevention programs have generally fallen short of controlling youth crime, there is every reason to believe that renewed efforts will be continued throughout the twenty-first century.

Bibliography:

- Akers, Ronald L. 1990. “Rational Choice, Deterrence, and Social Learning Theory in Criminology: The Path Not Taken.” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 81:653–76.

- Bartollas, Clemens. 2006. Juvenile Delinquency. 7th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Battin-Pearson, Sara R., Terence P. Thornberry, J. David Hawkins, and Marvin D. Krohn. 1998. “Gang Membership, Delinquent Peers, and Delinquent Behavior.” Juvenile Justice Bulletin, October.

- Becker, Howard S. 1963. New York: Free Press.

- Braga, Anthony A. 2003. “Serious Youth Gun Offenders and the Epidemic of Youth Violence in Boston.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 19:33–54.

- Breckinridge, S. P. and Edith Abbott. 1970. The Delinquent Child and the Home. New York: Arno Press.

- Brenzel, Barbara. 1983. Daughters of the State. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Chesney-Lind, Meda. 1989. “Girls, Crime and Women’s Place.” Crime and Delinquency 35:5–29.

- Chesney-Lind, Meda. 1995. “Girls, Delinquency and Juvenile Justice: Toward a Feminist Theory of Young Women’s Crime.” Pp. 71–88 in The Criminal Justice System and Women, edited by B. R. Price and N. J. Sokoloff. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Cloward, Richard A. and Lloyd E. Ohlin. 1960. Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of Delinquent Gangs. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Cohen, Albert K. 1955. Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Cook, Philip J. and John Laub. 1998. “The Unprecedented Epidemic in Youth Violence.” Pp. 27–64 in Crime and Justice, edited by M. H. Moore and M. Tonry. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Cook, Philip J. and Jens Ludwig. 2004. “Does Gun Prevalence Affect Teen Gun Carrying After All?” Criminology 42:27–54.

- Cornish, Derek and Ronald V. Clarke, eds. 1986. The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending. New York: Springer.

- Cortes, Juan B., with Florence M. Gatti. 1972. Delinquency and Crime: A Biopsychosocial Approach; Empirical, Theoretical, and Practical Aspects of Criminal Behavior. New York: Seminar Press.

- Daly, Kathleen. 1995. “Looking Back, Looking Forward: the Promise of Feminist Transformation. Pp. 447–48 in The Criminal Justice System and Women, edited by B. R. Price and N. J. Sokoloff. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Daly, Kathleen and Meda Chesney-Lind. 1988. “Feminism and Criminology?” Justice Quarterly 5:497–538.

- Elliott, Delbert S., Suzanne S. Ageton, and Rachelle J. Canter. 1979. “An Integrated Theoretical Perspective on Delinquent Behavior.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 16:3–27.

- Faust, Frederic and Paul J. Brantingham, eds. 1974. Juvenile Justice Philosophy. Paul, MN: West.

- Feld, Barry. 1999. Bad Kids: Race and the Transformation of the Juvenile Court. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Finestone, Harold. 1976. Victims of Change: Juvenile Delinquents in American Society. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Fishbein, Diana. H. 1990. “Biological Perspectives in Criminology.” Criminology 28:27–72.

- Glueck, Nelson and Eleanor Glueck. 1956. Physique and Delinquency. New York: Harper & Row.

- Gottfredson, Michael R. and Travis Hirschi. 1990. A General Theory of Crime. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Grasmick, Harold G., Charles R. Tittle, Robert J. Bursik Jr., and Bruce J. Arneklev. 1993. “Testing the Core Empirical Implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s General Theory of Crime.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 30:5–29.

- Heimer, Karen. 1995. “Gender, Race, and the Pathways to Delinquency.” Pp. 140–53 in Crime and Inequality, edited by J. Hagen and R. D. Peterson. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hirschi, Travis. 1967. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: California University Press.

- Jarjoura, G. Roger. 1993. “Does Dropping Out of School Enhance Delinquent Involvement? Results from a Large-Scale National Probability Sample.” Criminology 31:149–71.

- Johnston, L. D., P. M. O’Malley, J. G. Bachman, and J. E. Schulenberg. 2004. Monitoring the Future: Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Drug Abuse.

- Katz, Jack. 1988. Seductions of Crime: Moral and Sensual Attractions in Doing Evil. New York: Basic Books.

- Klein, Dorie. 1995. “The Etiology of Female Crime:A Review of the Literature.” Pp. 30–53 in The Criminal Justice System and Women, edited by B. R. Price and N. J. Sokoloff. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Krohn, Marvin D., Terence P. Thornberry, Craig Rivera, and Marc Le Blanc. 2001. “Later Delinquency Careers.” Pp. 67–93 in Child Development, edited by R. Loeber and D. P. Farrington. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Laub, James H. and Robert J. Sampson. 2003. Shared Beginnings, Divergent Lives Delinquent Boys to Age 70. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lauritsen, Janet L. 1993. “Sibling Resemblance in Juvenile Delinquency: Findings from a National Youth Survey.” Criminology 31:387–409.

- Lemert, Edwin M. 1951. Social Pathology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Leonard, Eileen. 1995. “Theoretical Criminology and Gender.” Pp. 55–70 in The Criminal Justice System and Women, edited by B. R. Price and N. J. Sokoloff. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Loeber, Rolf and M. Stouthamer-Loeber. 1986. “Family Factors as Correlates and Predictors of Juvenile Conduct Problems and Delinquency.” Pp. 29–149 in Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, edited by M. Tonry and N. Morris. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lombroso-Ferrero, Gina. 1972. Criminal Man According to Classification of Cesare Lombroso. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith.

- Lundman, Richard J., Paul T. McFarlane, and Frank R. Scarpitti. 1976. “Delinquency Prevention: A Description and Assessment of Projects Reported in the Professional Literature.” Crime and Delinquency 22:297–309.

- Lundman, Richard J. and Frank R. Scarpitti. 1978. “Delinquency Prevention: Recommendations for Future Projects.” Crime and Delinquency 24:207–20.

- Maguin, Eugene and Rolf Loeber. 1996. “Academic Performance and Delinquency.” Pp. 145–264 in Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 20, edited by M. Tonry. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Matsueda, Ross. L. 1992. “Reflected Appraisals: Parental Labeling, and Delinquency: Specifying a Symbolic Interactionist Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 97:1577–611.

- Matza, David. 1964. Delinquency and Drift. New York: John Wiley.

- Mazerolle, Paul. 1998. “Gender, General Strain, and Delinquency:An Empirical Examination.” Justice Quarterly 15:65–91.

- McCord, W. J., J. McCord, and Irvin Zola. 1959. The Origins of Crime. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Robert K. 1957. Social Theory and Social Structure. 2d ed. New York: Free Press.

- Mihalic, Sharon, Katerine Irwin, Abigail Fagan, Diane Ballard, and Delbert Elliott. 2004. Blueprints for Violence Prevention. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Miller, Jody. 2001. One of the Guys: Girls, Gangs, and Gender. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Jody and Scott Decker. 2001. “Young Women and Gang Violence: Gender, Street Offending, and Violent Victimization in Gangs.” Justice Quarterly 18:115–39.

- Moffitt, Terrie. 1993. “Adolescent-Limited and Life-CoursePersistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy.” Psychological Review 100:674–701.

- Moffitt, Terrie, Donald R. Lynam, and Phil A. Silva. 1994. “Neuropsychological Tests Predicted Persistent Male Delinquency.” Criminology 32:277–300.

- Moffitt, Terrie E., Avshalom Caspi, Michael Rutter, and Phil A. Silva. 2001. Sex Differences in antisocial behavior. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Piper, Elizabeth S. 1985. “Violent Offenders: Lone Wolf or Wolfpack.” Presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, San Diego, CA.

- Platt, Anthony. 1977. The Child Savers. 2d ed. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Reckless, Walter C. 1961. “A New Theory of Delinquency and Crime.” Federal Probation 24:42–46.

- Reiss, Albert J., Jr. 1976. “Setting the Frontiers of a Pioneer in American Criminology: Henry McKay.” Pp. 64–88 in Delinquency: Crime and Society, edited by J. F. Short. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rothman, David J. 1971. Discovery of the Asylum. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Sampson, Robert J. and James H. Laub. 1993. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Shah, Saleem A. and Loren H. Roth. 1974. “Biological and Psychophysiological Factors in Criminality.” Pp. 101–73 in Handbook of Criminology, edited by D. Glaser. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

- Shaw, Clifford R. 1929. Delinquent Areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Shaw, Clifford R. and Henry D. McKay. 1931. Social Factors in Juvenile Delinquency. Washington, DC: National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement.

- Shaw, Clifford R. and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Smart, Carol. 1976. Women, Crime and Criminology: A Feminist Critique. Boston, MA: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Shichor, David. 1980. “The New Criminology: Some Critical Issues.” British Journal of Criminology 20:1–19.

- Sutherland, Edwin H. 1947. Principles of Criminology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: J. P. Lippincott.

- Frank. 1938. Crime and the Community. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Thomas, William I. and Florian Znaniecki. 1927. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America. 5 vols. New York: Knopf.

- Thornberry, Terence P. 1987. “Toward an Interactional Theory of Delinquency.” Criminology 25:863–91.

- Thornberry, Terence P. 1989. “Reflections on the Advantages and Disadvantages of Theoretical Integration.” Pp. 51–60 in Theoretical Integration in the Study of Deviance and Crime: Problems and Prospects, edited by S. Messner, M. Krohn, and A. Liska. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Thornberry, Terence P., Marvin D. Krohn, Alan J. Lizotte, Carolyn A. Smith, and Kimberly Tobin. 2003. Gangs and Delinquency in Developmental Perspective. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Thrasher, Frederick. 1927. The Gang: A Study of 1313 Gangs in Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Triplett, Ruth Ann and G. Roger Jarjoura. 1994. “Theoretical and Empirical Specification of a Model of Informal Labeling.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 10:241–76.

- White, Herlene Raskin, Erich W. Labouvie, and Marsha E. Bates. 1985. “The Relationship between Sensation Seeking and Delinquency: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 22:195–211.

- Wilson, James Q. and Richard J. Herrnstein. 1985. Crime and Human Nature. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Wolfgang, E. Marvin, Terence P. Thornberry, and Robert F. Figlio. 1987. From Boy to Man: From Delinquency to Crime. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.