View sample sexual violence research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Sexual violence is endemic. More than one in five women report a lifetime experience of sexual assault from an intimate partner, while up to one-third of girls report their first sexual experience was forced ( Jewkes et al., 2002a). It is both a profound public health problem and human rights violation, while the shortand long-term consequences of it limit the potential of victims/survivors to achieve an optimum standard of health and well-being. Sexual violence violates multiple fundamental human rights, including the right to life, equality, liberty, security of persons, the right to be free from all forms of discrimination, and the right not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Despite this, it is one of the least researched of all forms of gender-based violence.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Sexual Violence: Definition

The World Report on Violence and Health defines sexual violence against women as:

any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed against, women’s sexuality, using coercion (i.e., psychological intimidation, physical force, or threats of harm), by any person regardless of relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work. (Jewkes et al., 2002a: 14a)

It can include a range of acts, including rape in marriage and dating relationships; rape by strangers; rape as a weapon of war; sexual harassment (including demands of sex for jobs or school grades); sexual abuse of the mentally ill or impaired; sexual abuse of children; forced marriage or cohabitation, including marriage of children; sexual torture; and forced prostitution and trafficking in women for sexual exploitation. It also includes forced abortion; denial of the right to use contraception or protect self from disease; and acts of violence against women’s sexuality such as female genital cutting and social virginity inspection. Sexual violence is predominantly experienced by women and girls, although it can be directed against men and boys.

Prevalence Of Sexual Violence

Sexual Assault

Research on sexual violence is critical in highlighting the extent of the problem, and strengthening public health services and prevention programs. In no country has there been a study of the prevalence of perpetration of sexual assault of intimate partners and other women or girls in a randomly selected sample of men from the community. There are therefore many unanswered questions about patterns of perpetration; however, research from North American and South Africa seems to suggest that men who rape are very likely to do so first during their teenage years and that repeat perpetration is very common (White and Smith, 2004). In all countries, only a very small proportion of men who are sexually violent are ever punished by law. The extent to which convicted sex offenders resemble the total population of sexual violent men is not known.

Globally, there has been more research conducted with women documenting their experience as victims/survivors, and most of the data available describe the prevalence of this. Differences in measures, definitions, and social meanings as well as underreporting limit data accuracy. Sexual violence is particularly stigmatized. In some settings victims are ostracized, abandoned, and even killed, and very commonly lesser manifestations of stigma limit disclosure and help-seeking. These include shame, blame, denial, fear of the consequences, fear of retribution, and a sense of inevitability that disclosure will not be helpful. It is estimated that at most one in ten sexual assaults are reported to the police and in many settings the proportion is much lower. Despite these limitations, available evidence provides valuable insights into the epidemiology of sexual violence.

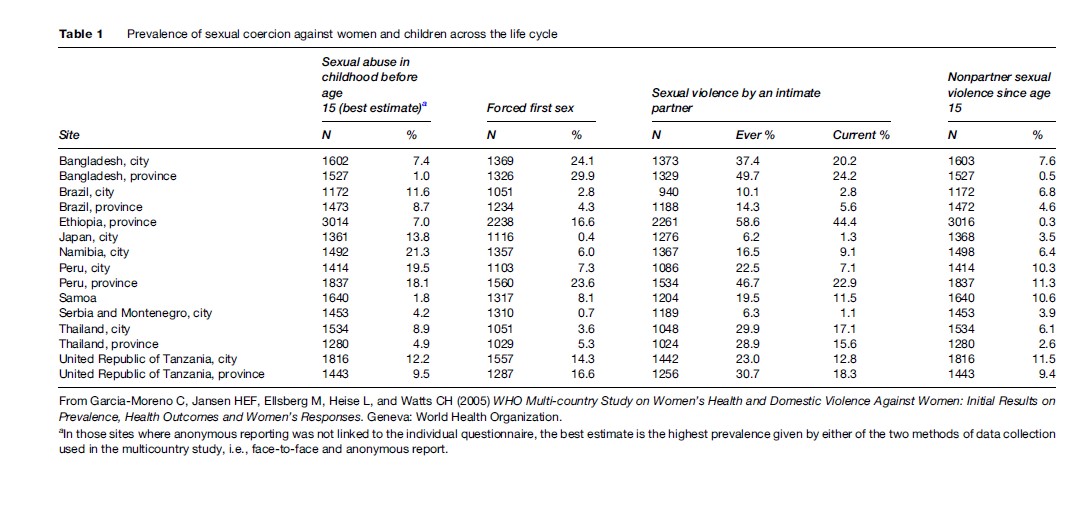

A global insight into the prevalence of sexual violence across the early and middle years of the life span is provided by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women (Garcia Moreno et al., 2005). In the study, randomly selected samples of women aged 16–49 years from ten different countries, often from rural and urban areas, were interviewed to create a data set of more than 24 000 women. The prevalence findings are summarized in Table 1.

Sexual violence in childhood, involving inappropriate acts of exposure, or touching, of genitalia, as well as penetration, is very common. It is experienced by both girls (most commonly) and boys, but globally very much less is known about the prevalence, consequences, and context of abuse of boys than girls. Much of it occurs in homes, where male family members are often perpetrators, but children are also often sexually abused by respected older people in the community. The WHO study found a prevalence of child sexual abuse of between 1 and 20%.

In many countries, schools are also places where girls are at considerable risk. In developing countries, school age girls may be forced by poverty into transactional sexual relationships with teachers or other older men in order to raise the money for school fees. Educational institutions are also settings in which sexual harassment and rape by teachers or fellow pupils occurs. In South Africa, the 1998 Demographic and Health Survey included questions about experience of rape before the age of 15 years and found that school teachers were the largest group of child rape perpetrators, responsible for 32% of the disclosed child rapes (Jewkes et al., 2002b). Research in Africa describes high levels of apathy among officials about this, with a lack of information among pupils and parents and a reluctance to believe girls who make allegations. Teachers are generally unwilling to report colleagues’ sexual misconduct and often see the behavior of boys as a normal part of growing up.

Research has increasingly shown that girls’ first sexual intercourse is often forced, and the younger the age at which this occurs, the greater the likelihood of it being forced (Table 1). Forced first sex is also particularly common in settings where women’s sexuality is more constrained and where sexual dominance by men is more strongly culturally sanctioned. The highest prevalence of first forced sex found in the WHO study, for example, was 30% in Bangladesh.

Intimate partner violence, usually defined as violence perpetrated by a current or ex-husband or boyfriend, encompasses both physically and sexually violent acts, which are usually located within a relationship that is characterized by a range of controlling and emotionally abusive dynamics. The prevalence of sexual intimate partner violence varies between settings and has been found to be as high as 44% (Table 1). In most settings, women are more at risk of being forced into unwanted sexual acts by an intimate partner than any other type of perpetrator.

Rape and attempted rape by acquaintances or strangers occurs in all settings with a prevalence of victimization as high as 12% (Table 1). Usually there is one perpetrator, but in some settings rape by more than one man commonly occurs and may even be ritualistic. A study from South Africa, where one-third of rapes reported to the police involve more than one perpetrator, found that 14% of young men disclosed in interviews having participated in group rape of a woman (Jewkes et al., 2006). Throughout history, rape has been used as a weapon of war. In recent years, for example, between 23 200 to 45 600 Kosovar Albanian women are believed to have been raped in the 1998–99 conflict with Serbia, and very high rates of gang rape have been reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo, often resulting in genital fistulae.

Sexual Trafficking

The Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights Aspects of the Victims of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Huda, 2006), defines trafficking in persons as:

the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

Evidence suggests that each year hundreds of thousands of women and girls throughout the world are bought and sold into prostitution and slavery. It is purportedly one of the fastest growing organized crimes.

Trafficked women and children are often trapped in slave-like conditions, with identification papers removed. In many cases, they may be led to believe that they have accepted domestic or waitressing work but they are taken to brothels, their passports confiscated, and they may be beaten, locked up and promised freedom only after earning their purchase price, travel and visa costs through sex work. This lucrative business has large profits and relatively few risks and has led to global networks of traffickers, often with mafia-style operations.

Harmful Traditional Practices

In many countries, there are traditional practices that are harmful to women and children, such as early and forced marriage, the offering of girls to temples to live a life of servitude often including prostitution, and giving girls to fetish shrines to serve as domestic and sexual slaves. Female genital cutting, which encompasses the removal of part, or all, of the external female genital tissue is estimated to effect 130 million girls worldwide and can lead to serious health problems. There has, however, been a shift in public opinion to traditional harmful practices, with an increasing recognition that they are violations of young girls’ rights and integrity, which must be stopped.

Sexual Violence Against Men

Men and boys are recognized as potential victims of sexual assault, but globally there has been little research on the frequency with which this occurs and the contexts. It is recognized that both men and women may coerce young men and boys into sex, but those forcing older men are invariably male. There is some evidence that the meaning of acts of coercion of men may vary according to whether the perpetrator is a man or a woman, but coercion of young men into sex by women needs to be better understood and more widely recognized as a problem (Marston, 2005).

Circumstances in which coercion of men and boys occurs include child sexual abuse, forced sexual initiation, sexual harassment and coerced sex in schools, sexual harassment in families and from close relatives, and sexual violence experienced in police cells, prisons, during crime and during war. Rape of male prostitutes is also a well-recognized and common problem (Jewkes et al., 2002a). In some settings forced heterosexual initiation of boys is disclosed in surveys nearly as frequently as that of girls, with up to one-third of boys reporting this. However, generally the prevalence of coercion of boys and men is much lower than that reported of women (Jewkes et al., 2002a). Sexual assault of men is also subject to underreporting, and this is particularly influenced by social expectations that normal men are heterosexual and always open to sex with women, and fears that rape by a man can make a man gay.

Understanding Perpetration Of Sexual Assault

Sexual violence is a subcategory of gender-based violence; in other words, it is inherently rooted in the lower power that women have in a society compared to men. Within societies there is a range of social expectations, behavioral norms, and values that stem from this, which vary between settings. They often include expectations that women and girls will be under the control of men; that men have sex as a right within marriage; that women should not have sexual desires or a right to sexual pleasure; that sexually aroused men cannot control themselves; and that women and girls are responsible for ensuring that they do not arouse inappropriate sexual desires in men. A nexus of power and control lies at the heart of explanations of why men rape. Rape is an act through which men communicate to their victim about their powerfulness, as well as one through which they may communicate with themselves, through the experience of power in the act of rape. Thus rape may be an act of punishment and an expression of holding power over a victim, and it can also be an act through which perpetrators affirm to themselves a sense of power that they may not feel in other respects in their lives.

Globally, the base of research on risk factors for sexual assault perpetration has been narrow, and the great majority of what is known comes from North American and South Africa. Nonetheless, many of the findings from these settings point to considerable commonality in underlying factors. In North America, a multifactorial model known as the Confluence Model (Malamuth et al., 1991) was developed to explain the interconnections among factors associated with sexual assault; it has been particularly influential in the field. The model has two paths through which factors are believed to operate to influence sexual assault perpetration and each has been empirically shown to independently predict perpetration, but also to work synergistically such that men who score highly on both paths are more likely to be sexually coercive.

The first path has been dubbed hostile masculinity and at the heart of this path are feelings of insecurity and defensiveness in relationships toward women, with sex being an act of power and dominance rather than love. Sexually violent men have been shown to be more likely to be hostile toward women, to perceive women as hostile to them, to mistrust women’s affective expression, and thus be more likely to interpret assertiveness in women’s interactions with them as hostility (Malamuth et al., 1991; Abbey et al., 2004a). The factors associated with or indicators of hostile masculinity are a high level of acceptance of interpersonal violence, relative isolation from women, and perceptions of sex as an act between adversaries. Sexually violent men, especially men who coerce sex more than once, are more likely to lack empathy for their victims, lack remorse (both features of psychopathy), and consider victims to be responsible for rape (Abbey et al., 2004a).

The second path is the sexual promiscuity/impersonal sex path. At the heart of this are ideas of sex as a game to be won or for physical gratification, and not for emotional closeness or intimacy. This path builds on the observation that men are more likely to rape if they have experienced a range of trauma in childhood and this is seen to influence their later sexual practices and preferences. The experience of trauma in childhood is postulated to reduce the ability of men to form loving and nurturing attachments, and thus results in an orientation to impersonal sexual relationships rather than sex in the context of emotional bonding and short-term sex-seeking strategies. Malamuth et al. (1991) originally emphasized experience of childhood sexual abuse and witnessing violence between parents in childhood, but other authors have found an association with a wider range of experience of abuse (Knight and Sims-Knight, 2003; Jewkes et al., 2006). Experience of trauma in childhood increases the likelihood of engagement in delinquent behavior, and rape is often perpetrated in the context of peer-related acts of delinquency. Sexually violent men are more likely to have more sexual partners than other men. Malamuth et al. (1991) argue that men who develop a relatively high emphasis on sexuality, particularly with sexual conquest, as a source of peer status and self-esteem, may use various means, including coercion to induce girls into sexual acts. In this regard, peer pressure to have sex may also encourage some men to force sex (Jewkes et al., 2006).

A number of rape researchers have argued that some important factors are missing from the Confluence Model. Alcohol plays a role in a high proportion of rapes (Abbey et al., 2004b). It is a situational factor (Abbey et al., 2004b) but may have a more complex role. Sexual assaults are very frequently associated with alcohol consumption. Alcohol has psychopharmacological effects of reducing inhibitions (like some drugs, notably cocaine), clouding judgment and enabling a greater focus on the short-term benefits of forced sex. It may also act as a cultural time-out for antisocial behavior. Thus men are more likely to act violently when drunk because they do not feel they will be held accountable for their behavior (Abbey et al., 2004b). Some forms of group sexual violence are associated with alcohol drinking and here drinking alcohol forms part of the group bonding with collectively reduced inhibitions and individual judgment ceded to that of the group.

The Confluence Model provides an understanding of factors associated with rape perpetration that overwhelmingly emphasizes individual characteristics. Research from outside the discipline of psychology suggests that there are several social factors that are important. Social and economic status is one such factor, but unfortunately information on the association of these with rape perpetration is limited. Some researchers (e.g., Bourgois, 1995) have argued that in the face of poverty and unemployment, men lack paths through which they may demonstrate success and may rape in an effort to reclaim, however transiently, a sense of powerfulness. Others have observed that in some research men who rape have come from relatively more privileged backgrounds and were relatively more powerful than the women they raped (Duvvury et al., 2002; Jewkes et al., 2006). In these circumstances, their acts are better explained as stemming from an exaggerated sense of sexual entitlement. These explanations are not necessarily contradictory, because sexual assault occurs in a range of different contexts and may at different times have different roots.

A unifying idea between them is the location of sexual violence within a framework of ideas about manhood, which is developed and sustained not just at an individual, but also at a community or societal level. Socially constructed ideas about manhood are used by individual men in their self-evaluations of success and in development of their expectations and ideas about the appropriateness of particular approaches to and patterns of behavior. In South Africa, researchers have demonstrated a cluster of closely correlated male behaviors, including sexual and physical violence against women, having many sexual partners, transactional sex, and alcohol abuse, which link sexual conquest, risk taking, and violence with rape (Jewkes et al., 2006). These are dimensions of a particular model of masculinity, which has been shown to change in response to an intervention that builds gender equity and ideas of sexual and social responsibility.

One of the community or societal level influences on sexual violence is the extent to which it is perceived to be an act that is socially stigmatized and liable to be punished. This is very closely linked to the status of women. Rape is one of the few acts of violence where the victims (usually women or girls) are very likely to be blamed equally or more severely than the perpetrator. This reflects the social position of women. In settings with greater gender equity, social understandings of sexual violence are more unequivocal, raping is stigmatized, and sanctions for perpetration are perceived as likely and feared. At an individual level, women and children are more likely to be victims of sexual violence if they are of lower social status overall, as well as with respect to men who rape. Men often perceive that they are less likely to face consequences if their victim is of lower social status or in some way socially devalued (for example a mentally ill person or a sex worker). Rape by a nonpartner is often opportunistic and women and girls of lower socioeconomic status are more often in situations of vulnerability, for example walking on open land because they lack the resources to use transport or living somewhere that can be more easily broken into.

Health Consequences Of Sexual Assault

Sexual violence has a range of health consequences, both short-term and long-term. The most important immediate consequences are usually symptoms of psychological distress, experienced as shock, fear, and feelings of helplessness; hyperarousal caused by concerns for personal safety, and high levels of anxiety. This may be accompanied or followed by depression and, if prolonged, may develop into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Rape survivors not infrequently attempt suicide. In the longer term, especially where there has been repeated violations and where it has occurred in childhood, substance abuse is more common in sexual violence survivors. The psychological impact also includes fundamental changes in victims’/survivors’ perception of self, which impacts on other areas of their lives, notably their relationships with men. Many victims/survivors struggle to have sexual relationships with men. As a group they are more likely to engage in sexual risk taking including starting sexual relationships earlier, having more partners, older partners, transactional sex and more unsafe sex. They are also more likely to have violent partners.

There are many important physical consequences of sexual violence. Pregnancy may occur in the absence of contraception and is particularly stressful if termination is not an option. Sexually transmitted infections may be acquired and, if untreated, can result in infertility, pelvic pain, and pelvic inflammatory disease. In high-prevalence settings, the transmission of HIV during sexual assault is a major concern for victims/survivors. Genital and other injuries may also occur in the course of sexual violence. Very violent rape, particularly gang rape, has been associated with very severe injuries including the development of genital fistulae and, if the woman is pregnant, pregnancy loss. The injuries associated with rape are at times fatal, these are known as rape homicides. In South Africa, rape is suspected in 16% of female homicides.

Ethics Of Research On Sexual Violence

All studies face the challenge of ensuring that the research is of high quality, benefits are maximized, and the potential for doing harm through the research is kept to a minimum. The very sensitive nature of sexual violence poses a unique set of challenges and a range of ethical and safety issues need to be considered and addressed prior to embarking on such research. In addition to the established codes of practice related to ethics in research, a number of specific issues need to be considered. The sensitive nature of the research makes it particularly important that every effort is made to ensure that benefits outweigh the possibility of harm, and for this reason it is important that the benefits and use of research on sexual violence are defined and assessed before research is commenced. The research must be methodologically sound and in every respect built on current experience and best practice. This is particularly important with respect to the approaches to data collection and questionnaire design. Where data are gathered from survivors of sexual violence, a provision should be made to make psychological support available to those disclosing violence. Research team members may experience vicarious trauma and they must be carefully selected and receive relevant and sufficient training and ongoing support. Both the research participants and the team may have their safety endangered by conducting research on sexual violence. Particular consideration needs to be given to ensuring confidentiality of the research, as well as of individuals included in studies.

Involving children in sexual violence research is important if we are to adequately understand their needs. However, special care and thought is needed beforehand; experts on research with children need to be consulted to ensure that methods used are appropriate and that all possible risks have been considered. Parents or care givers need to be consulted about the research and there may be mandatory reporting requirements that need to be followed if abuse is disclosed.

Research with men as perpetrators also entails a particular set of considerations. When conducted well, research on rape presents opportunities for men to confront the meaning of acts of sexual violence and this can play a constructive role in helping them to face up to what they have done and ultimately change their self-evaluation. However, there is a risk with less rigorous research of collusion with perpetrators of violence, which potentially could reinforce rape-supportive attitudes, or even encourage repeated acts of violence. Researchers may find the imperative of remaining neutral and detached very challenging in the face of accounts of perpetration of assault. Studies of rape perpetration need to be conducted in a manner that ensures that there is a balance between protecting the confidentiality of research participants while not suppressing information that could impact on the safety of others.

The World Health Organization has published ethics guidelines for research on domestic violence, with trafficked women and for research on sexual violence in emergencies. These documents are particularly useful resources for researchers planning work on sexual violence.

Responding To Sexual Assault In The Health Sector

Victims/survivors of sexual assault have a set of health needs that health services have to be in a position to address. Psychological support is of great importance and victims/survivors need to start to feel safe, regain a sense of control, and to recognize the psychological symptoms that they experience for what they are and to know that very often they are self-limiting. Women of reproductive age may require emergency contraception or termination of pregnancy. All victims/survivors need treatment for possible sexually transmitted diseases, and in all but the lowest prevalence settings prophylaxis against HIV is also needed. Injuries sustained may require treatment and in many countries there is an established procedure for examinations and documentation of injuries for legal purposes. This is often accompanied by the collection of forensic evidence. Mental health services are needed to help victims/survivors who have longer-term mental health needs.

In most countries, health services for victims/survivors have been relatively neglected. Studies describing post-rape health services around the world highlighted important gaps in many countries (Christofides et al., 2005). These include inequitable service provision, as many of the countries have first-rate services in a small number of centers, with trained sensitive staff, good community participation, clinical protocols, psychological support, and good follow-up after the initial contact. There is a very substantial gap in most countries between the best and the normal (or worst) facilities and a need for great improvement to the majority of services. In many countries, basic clinical care after rape is deficient in important respects, particularly psychological support is often not provided and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases is often inadequate. There is considerable variation between countries and within countries as to whether sexual violence patients are seen by designated service providers or generalist staff. The latter group are commonly almost completely unprepared for caring for sexual assault victims/survivors, because undergraduate medical and nursing courses generally devote very little, if any, time to teaching about gender and gender-based violence. Generalist staff may see rape victims/survivors infrequently, making it less likely that they would make special efforts to learn more about their care unless they were particularly motivated for other reasons. The attitudes of staff toward sexual assault victims/survivors have a very important impact on the quality of care provided (Christofides et al., 2005). Staff often hold the same judgmental attitudes toward victims/survivors that are prevalent in the general population, and this poses a barrier to providing good care. Facilities for caring for victims/survivors after rape are often deficient in important respects, and the best services have a dedicated suite with washing facilities and a private waiting area.

In an attempt to improve the health sector response to sexual violence internationally, the World Health Organization has produced guidelines for medicolegal care for victims of sexual violence (World Health Organization, 2004). These are a valuable tool that can be used to improve health services by providing health-care providers with the knowledge and skills necessary to understand the needs and concerns of victims of sexual violence, provide quality health services, and carry out accurate and ethical collection of forensic evidence. These can most effectively be used within a framework of a national health sector policy on sexual violence.

Preventing Sexual Violence

Primary prevention of sexual violence is a substantially neglected area, but one that needs to be prioritized. There is a considerable need for research, particularly to understand perpetration, and to develop and evaluate approaches to prevent this. Prevention needs to be addressed both through individual-level interventions and community or society-level interventions that seek to change social norms and the acceptability of sexual violence. There are two individual-level interventions that have been rigorously evaluated and shown to reduce perpetration. The first is the Safe Dates Programme (Foshee et al., 2004), which was developed to address sexual and physical violence occurring in dating relationships. It was shown to be effective in a North Carolina school population in reducing sexual and physical violence in dating relationships 4 years after the intervention. The Stepping Stones Programme ( Jewkes et al., 2002c) is a gender transformative HIV prevention programme that seeks to change risk taking and antisocial models of masculinity and through doing this promote sexual health as well as building gender equity. It has been shown to be effective in rural South African youth with an effect measured 2 years after intervention. These interventions show that it is indeed possible to change men’s violent behavior. They require further study, adaptation, and testing in other settings. Many other interventions are used, and these need to be subjected to the same level of evaluation in order to create a knowledge base for evidence-based rape prevention.

Social norms related to the status of women and the acceptability of rape are also important. In this regard, general interventions to improve the status of women would be expected to impact on sexual violence. Legislation is needed to provide an appropriate legal framework for defining and responding to sexual violence, policy is needed in government departments, and governments need to show a political commitment to efforts to eradicate sexual violence. The responsiveness of police to victims when they report sexual assault, as well as health and other services, sends a powerful message about the way in which a society views the crime. This in turn will have an impact on general acceptability, and through this its prevalence. A key part of a comprehensive public health response to sexual violence necessarily involves ensuring that a society learns to speak with one voice in showing no tolerance for sexual violence.

Bibliography:

- Abbey A and McAuslan P (2004a) A longitudinal examination of male college student’s perpetration of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72: 747–756.

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, and McAuslan P (2004b) Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behaviour 9: 271–303.

- Bourgois P (1995) In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Christofides N, Jewkes R, Webster N, Penn-Kekana L, Abrahams N, and Martin L (2005) Other patients are really in need of medical attention: The quality of sexual assault services in South Africa. World Health Bulletin 83: 495–502.

- Duvvury N, Nayak MB, Allendorf K, et al. (2002) Links between masculinity and violence: Aggregate analysis. In: Men Masculinity and Domestic Violence in India. Washington, DC: ICRW.

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Fletcher Linder G, Benefeld T, and Suchindran C (2004) Assessing the long term effects of the safe dates programme and a booster effect in preventing and reducing adolescent dating violence victimisation and perpetration. American Journal of Public Health 94: 619–624.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HEF, Ellsberg M, Heise L, and Watts CH (2005) WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women: Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Huda S (2006) UN Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Trafficking: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights Aspects of the Victims of Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/569066?ln=en.

- Jewkes R, Sen P, and Garcia-Moreno C (2002a) Sexual Violence. In: Krug EG, et al. (eds.) World Health Report on Violence and Health, pp. 148–181. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Bradshaw D, and Mbananga N (2002b) Rape of girls in South Africa. The Lancet 359: 319–320.

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, and Jama N (2002c) Stepping Stones. A training manual for sexual and reproductive health, communication and relationship skills, 2nd edn. Pretoria, S. Africa: Medical Research Council.

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Koss MP, et al. (2006) Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Social Science and Medicine 63: 2949–2961.

- Knight RA and Sims-Knight JE (2003) The developmental antecedents of sexual coercion against women: testing alternative hypotheses with structural equation modelling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 989: 72–85.

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, and Tanaka JS (1991) Characteristics of aggressors against women: testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59: 670–681.

- Marston C (2005) Pitfalls in the study of sexual coercion: what are we measuring and why? In: Jejeebhoy S, Shah I and Thapa S (eds.) Sexual Without Consent. Young People in Developing Countries. London: Zed Press.

- White JW and Hall Smith P (2004) Sexual assault perpetration and re-perpetration: from adolescence to young adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behaviour 31(2): 182–202.

- World Health Organization (2004) Guidelines for Medico-legal Care for Victims of Sexual Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Bachar K and Koss MP (2001) Closing the gap between what we know about rape and what we do. In: Edleson J and Renzetti C (eds.) Handbook of Research on Violence Against Women, pp. 117–142. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Jewkes R and Abrahams N (2002) The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science and Medicine 55: 153–166.

- Jejeebhoy S (ed.) (2005) Sex Without Consent. Young People in Developing Countries. London: Zed Books.

- Koss MP (1993) Detecting the scope of rape. A review of prevalence research methods. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 8(2): 198–222.

- Leach F (2003) An Investigative Study of the Abuse of Girls in African Schools. Department for International Development: Educational Papers No. 54, DFID, August 2003.

- Malamuth N (2003) Criminal and non-criminal sexual aggressors. Integrating psychopathy in a hierarchical-mediational confluence model. Annnals of the New York Academy of Sciences 989: 33–58.

- World Health Organization (2003) WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Interviewing Trafficked Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2007) WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Researching, Documenting and Monitoring Sexual Violence in Emergencies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2001) Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Guidelines for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO/FCH/GWH/01.1. https://www.who.int/gender/violence/womenfirtseng.pdf).