Sample Crime And Ethnicity Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

This research paper explores research regarding race, ethnicity, and crime. It focuses on the disproportionately high incidence of racial and ethnic minorities caught up in the justice systems of Western countries and on the reasons behind these disparities.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Race, Ethnicity, And Crime And The Limitations On Research

The term ‘race’ once referred to the ‘major biological divisions of mankind’ (Caucasoid, Negroid, and Mongoloid), as characterized by skin color, hair texture, and other physical features (Walker et al. 1996). This notion has fallen into disrepute for lack of scientific validation. Race is now recognized as a social construct used by groups seeking to delineate themselves from others. Ethnicity is a similar concept that principally refers to the countries from which an individual’s heritage can be traced (e.g., ‘Hispanic’ refers to those with Spanish ancestry), although it is also associated with language, religion, cultural practices, and self-perception. The meanings of these terms continue to be debated, and usage is not consistent internationally. In Germany, for instance, the term Auslander (foreigner) includes ethnic and racial differences in its vague and elastic scope. In England and Wales, researchers consider Blacks to be ethnic minorities, but offenses against them are sometimes referred to as being ‘racially’ motivated.

Crime typically is defined as ‘a social harm that the law makes punishable’ (Garner 1999). Examples of crime range from white-collar crimes and/organized crime, to murder and hate crimes. This research paper will focus on conduct often referred to as ‘street crime’ (also known in the US as Index Crime: murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, burglary, aggravated assault, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson), because current records provide the best data for analysis of variation in offending and victimization by race and ethnicity.

Analysis is constrained by the difficulty in obtaining reliable crime statistics. Such data are collected regularly in Western countries; however, even where crime data is available, the race and ethnicity of victims or offenders are rarely recorded. Only the US officially records and publishes data regarding an individual’s race beginning at arrest and continuing to incarceration, and even there data has reliability problems (see the subsection entitled The Quality of Criminal Justice Data on Race and Ethnicity, in Walker et al. 1996). Lawmakers in many countries have chosen not to record racial and ethnic identification data for ethical reasons. Though the reluctance of Europeans to compile data regarding the ethnicity of offenders and victims is hardly surprising, given the legacy of Nazi Germany, the decision to forgo collection is equally problematic. Comparing existing data cross-nationally can be difficult because each country has different laws and processes, research traditions, and immigration histories, but these concerns are not insurmountable.

1.1 Racial and Ethnic Disproportion in Justice Systems

Tonry (1997) notes that ‘members of some disadvantaged minority groups in every Western country are disproportionately likely to be arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for violent, property, and drug crimes.’ Whether or not this is a more universal phenomenon is as yet unknown, as research has largely been limited to English-speaking and European countries. Regardless, what is now known is disturbing enough. Racial disparities in arrest and incarceration have historically been of particular concern to re-searchers in the US, and it is with that data that this investigation begins.

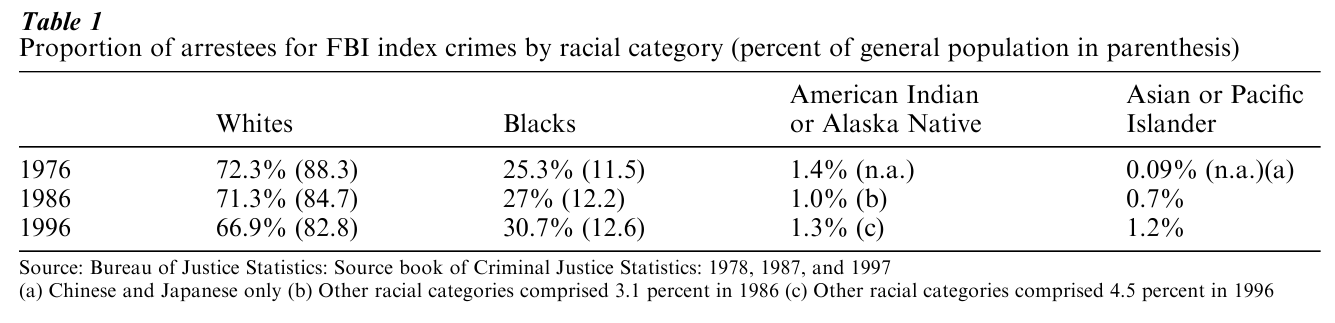

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has collected crime data since 1930 and annually produces the Uniform Crime Report (UCR). The UCR details arrest data for four racial groups (White, Black, Native American, and Asian), but it does not include ethnicity. These data are necessarily incomplete, as they only reflect crimes reported to the police, yet they reveal the stubborn stability of racial disproportion in US arrestees for Index crimes (Table 1).

Clearly, White Americans are the most numerous arrestees, but African Americans are arrested at rates that greatly exceed their representation in the population (about 12 percent). Though the data in Table 1 are aggregated, the racial disparity holds in each Index crime category. In 1996, African Americans were arrested at a rate disproportionate to their representation in the general population ranging from 1.9 times for arson to 4.6 times for robbery.

Research indicates racial and ethnic disparities in US jail and prison populations as well. In 1990, 14 percent of jail inmates were Hispanics, who composed only 9 percent of the general population. More notable is the fact that in 1992, 27 percent of federal prison inmates were Hispanic. US jail and prison data revealed that in 1990, 47 and 51 percent of each population was African American, respectively; the percentage of African American prison inmates has exhibited an upward trend since the 1920s. In 1997, 1,083 of every 100,000 American Indians were in jail— the highest rate for any race.

The US is not alone in exhibiting racial and ethnic disparity in arrests and imprisonment. Australian records, for example, indicate disparity in the arrest of Aborigines—considered a racial minority in that country. Aborigines were almost 8 times more likely to be arrested than non-Aborigines in 1990; the rate increased to 9.2 by 1994. Additional data show that Aboriginal juveniles particularly are likely to be arrested or detained. Data from 1993 reveal ethnic or racial disparities in the prisons of England, Wales, and Canada. Blacks (people of West Indian, Guyanese, and African origin) represented 11 percent of the male English and Welsh prison population, while comprising only 1.8 percent of the young adult males in the general population. Aggregating across all Canadian provinces, researchers found that in 1993–1994, when about 3.7 percent of the Canadian general population was Aboriginal, Aborigines composed 17 percent of provincial prison admittees. Blacks are also over- represented. Data from Ontario correctional facilities reveal a prison admission rate of 705 per 100,000 for whites, 1,992 per 100,000 for Aboriginals, and 3,686 per 100,000 for Blacks.

Notably, while some minorities are overrepresented in various criminal justice systems, others are under- represented, either in the aggregate or in arrest rates for specific offenses. In England, the rates of imprisonment among Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis are generally lower than that of whites, despite their generally poorer economic position. Likewise, a 1992 profile of US prison populations showed that Asians were underrepresented. Asians comprised 3 percent of the general population, yet they made up only about half of one percent of state inmates and just over 1 percent of federal inmates.

Thus, minorities are over and underrepresented in Western justice systems—usually the former. Why?

3. Reasons For Racial And Ethnic Disproportion In Justice Systems

The debate concerning minority overrepresentation in justice system processing has largely centered around two questions. Are racial and ethnic disparities the result of discrimination by criminal justice system actors? Or are they the result of disproportionate offending? Current research strongly suggests that racial and ethnic disproportionate representation in international justice systems results from both factors.

3.1 Evidence of Discrimination

The evidence does not suggest that bias is systematic: it does not afflict Western justice systems at all levels, in all cases, and at all times. Rather, it suggests that in certain cases, places, and times, minorities are more likely than majority members to face discrimination in interactions with justice system components. Four arenas evidencing bias are worth discussing briefly: ‘Neutral’ processes, police practices, drug law enforcement, and the death penalty.

3.1.1 ‘Neutral’ Processes. Research has confirmed that two practices, designed to be ‘race neutral’ in implementation, operate to the disadvantage of minorities on a regular basis: pretrial detention, and plea-bargaining. Though it seems logical to hold before trial those most likely to flee, international scholars have discovered that the characteristics associated with flight risk are more likely to be present in the minority population than in the majority, which results in racial disparities in pretrial detention. Similarly, minorities are less likely to plead guilty. Research indicates that this tendency is shaped by and contributes to the beliefs many minorities have about justice system bias.

3.1.2 Police Practices. The first experience many minorities have with the criminal justice system comes through contact with the police. The police function entails vast enforcement discretion, so the possibility of abuse of authority is ever-present. In the countries in which minorities are overrepresented in the justice system, there is also minority dissatisfaction with police practices. Reports of brutality and unnecessary stops, searches, and arrests fuel these views. In a 1994 US study, 47 percent of African Americans surveyed reported having been harassed by police, while only 10 percent of Whites reported harassment. Researchers in Maryland found that African Americans were the subject of 77 percent of vehicle searches conducted by state troopers in 1995; no contraband was found in 67 percent of the cases. Similarly, the police forces of Glasgow, London, Ottawa, and Toronto are among those who have come under scrutiny recently.

It is possible that police practices impacting primarily minorities also affect the opinions of the police held by the majority population. In a survey conducted in 1981 and 1990 in 20 countries, only a minority of all citizens polled, ranging from a high of about 40 percent in Britain to a low nearing 5 percent in Argentina, expressed ‘a great deal’ of confidence in their nation’s police; in all but four of these countries the percentage had declined by 1990.

3.1.3 Drug Law Enforcement. Since the 1980s, the problem of race, ethnicity, and crime in the US and elsewhere has been driven by drug laws and policies that have resulted in the rapid rise in the incarceration rate of minorities. The increase in the Black prison population in the US, England, and Wales is obviously tied to drug law violations. In these countries minorities tend to be convicted of relatively low-level drug offenses at rates much higher than those of the majority of individuals. Scholars have concluded that the stark racial disparities in arrests and incarceration resulting from drug law enforcement are difficult to justify given the small gains in crime control from these policies (Tonry 1995, Meares 1998).

3.1.4 The Death Penalty. This issue is of particular concern to scholars in the US, as it is the only Western democracy still imposing this sentence. Examination of sentencing practices indicates that the victim’s race, not the offender’s, most often deter-mines whether or not the defendant will receive the death penalty. Those who murder Whites are more likely to receive the death penalty than those who murder Blacks. African American defendants charged with murdering Whites are most likely to receive the ultimate sanction.

Despite this evidence, the US Supreme Court has refused to void the death penalty, finding in McCleskey v. Kemp (1987) that defendants must demonstrate, in addition to discriminatory effect, that the prosecutor’s decision to pursue the death penalty in a particular case was the result of racial animus. Today, US death rows are still predominantly minority. Not one death row defendant has yet been able to demonstrate the evidentiary requirements stipulated by McCleskey.

3.2 Evidence From Victimization Studies

To determine the extent of discrimination in inter-national justice systems, some scholars have looked to victimization surveys, reasoning that if arrest data matches victimization reports, the racial disparities evidenced in arrests could be explained by disproportionate offending rather than by bias.

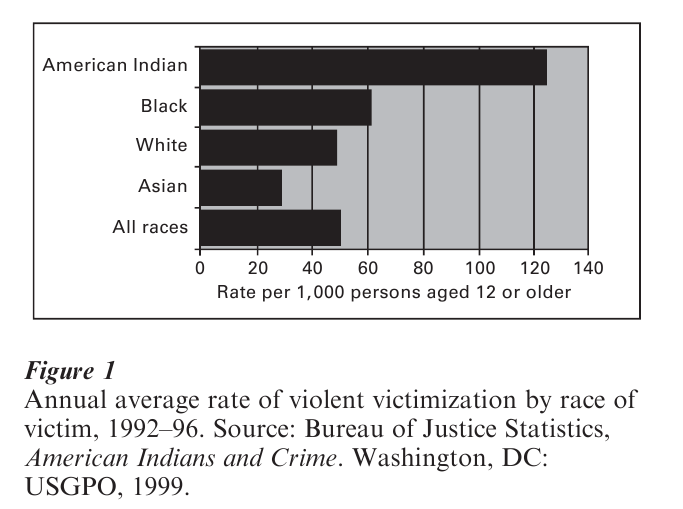

Among Western countries, only the US, England, Canada, and The Netherlands conduct long-term national victimization studies. US data shows that minorities fall victim to violent crime at a rate that exceeds their representation in the population (Fig. 1). US data also shows that violent crime is largely an intraracial event. From 1976 to 1996, 94 percent of cases involving Black murder victims involved a Black offender. The corresponding percentage was 85.6 for Whites.

The victimization data largely points away from invidiously or blatantly discriminatory targeting of offenders by the justice system. Instead, the data suggests that differential rates of offending by racial and ethnic groups contribute a great deal to the disparity in the US justice system. Hindelang’s (1978) classic study shows significant correspondence between the distribution of the perceived race of offenders from victimization survey results and the distribution of arrestees by race from official statistics. While there are well-documented limitations to this approach, existing research has prompted Tonry (1997) to conclude that ‘in countries in which research has been conducted on the causes of racial and ethnic disparities in imprisonment, group differences in of-fending, not invidious bias, appear to be the principle cause.’

4. Why Do Minorities Disproportionately Offend?

Minority groups overrepresented in justice systems tend to be economically and socially disadvantaged, especially compared to the majority. In many cases this is the result of historical discrimination, or is tied to the group’s recent immigration to their new national home. Often racial and ethnic minority groups are segregated geographically from other groups. Social disorganization theory postulates that the geographical concentration of poverty, along with factors such as joblessness and family disruption, negatively impacts the ability of community-level institutions to mediate crime (Shaw et al. 1929, Sampson 1989). This theory helps to explain why some disproportionately minority areas—especially urban ones—exhibit high crime rates. But it does not explain why particular individuals do or do not engage in crime. It is primarily for this reason that attempts to incorporate the notion of ‘rotten social background’ as a legal excuse for crime commission have been unsuccessful.

Other explanations for minority involvement in the criminal justice system emphasize power and social relationships over economic disadvantage. Conflict theory suggests that discriminatory justice practices are simply another expression of the disproportionate power distribution in society. The dominant group can and does use available means to maintain its grip on power (Liska 1992). Cultural conflict theory maintains that heterogeneous societies tend toward disparate values and are thus more vulnerable to crime (Sellin 1938). This theory suggests that some minority groups, for various reasons, do not accept majority values, increasing the likelihood of criminal behavior. Finally, social strain theory sees increased criminality as one of several responses to the tension inherent in a society in which many lack the means to obtain dominant goals in the generally agreed upon manner (Merton 1957). Rebellion and retreatism (e.g., through drug use) are among the other reactions to this type of societal stress. While each of these theories has certain merits, none does a particularly good job of explaining why some disadvantaged minorities are disproportionately underrepresented in criminal justice systems.

5. Conclusion

Racial and ethnic disparities apparent in Western justice systems will increase rather than decrease, at least in the short term, as a result of increasing rates of immigration to Western countries by racial and ethnic minorities and the worldwide trend toward urbanization. This problem is not confined to the Western countries emphasized here. One need only consider the social landscape of South Africa (and the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization) to see this. The main impediment to exploration of these issues worldwide is the profound lack of data. Thus, the challenge of promulgating useful crime policy without unnecessarily impacting racial and ethnic minorities will continue to be considerable without good data to help determine the scope and substance of the problem.

Bibliography:

- Bureau of Justice Statistics 1999 American Indians and Crime. USGPO, Washington, DC

- Garner B A 1999 (ed.) Black’s Law Dictionary. West Gray, St. Paul, MN

- Gottfredson M R 1979 (ed.) Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics—1978. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Gross S R, Mauro R 1989 Death and Discrimination: Racial Disparities in Capital Sentencing. Northeastern University Press, Boston

- Hindelang M 1978 Race and involvement in common-law personal crimes. American Sociological Review 43: 93–109

- Inglehart R (ed.) 1994 World Values Survey, 1981–1984 and 1990–1993. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI

- Jamieson K M, Flanagan T J (eds.) 1998 Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics—1987. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Liska A E (ed.) 1992 Social Threat and Social Control. State University of New York, Albany, NY

- Maguire K , Pastore A L (eds.) 1998 Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics—1997. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Mann C R 1993 Unequal Justice: A Question of Color. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, IN

- Meares T L 1998 Social organization and drug law enforcement. American Criminal Law Review 35: 191–227

- Merton R K 1957 Social Theory and Social Structure. Free Press, New York

- Russell K K 1998 The Color of Crime: Racial Hoaxes, White Fear, Black Protectionism, Police Harassment, and other Macroaggressions. New York University Press, New York

- Sampson R J 1989 Community structure and crime: Testing social disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology 94: 774 –802

- Sellin T 1938 Culture Conflict and Crime, Bulletin 41. Social Science Research Council, New York

- Shaw C R, Forbaugh F, McKay H D 1929 Delinquency Areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Tonry M 1995 Malign Neglect: Race, Crime and Punishment in America. Oxford University Press, New York

- Tonry M (ed.) 1997 Ethnicity, Crime and Immigration: Comparative and Cross-national Perspectives. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Uniform Crime Reports for the United States 1996 USGPO, Washington, DC

- Walker S, Spohn C, DeLone M 1996 The Color of Justice: Race, Ethnicity, and Crime in America. Wadsworth, Washington, DC