Sample Phylogeny and Reticulation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Why do human cultures and languages form patterns of differentiation through time and across space, and how do such patterns form? Why do language families and archeological cultures exist? Application of bio-logical concepts such as ‘phylogeny’ (evolutionary history of a genetically-related group of organisms) within the anthropological, archeological, and linguistic disciplines might seem a little unwarranted since culture is transmitted through both Mendelian (phylogenetic) and Lamarckian (reticulate) processes (Boyd and Richerson 1985, Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman 1981, Durham 1991). Thus, the transmission of cultural knowledge and language from generation to generation cannot be precisely equated with genetic inheritance in terms of mechanism. But the terms phylogeny and reticulation can have direct value in understanding the creation of many historical and ethnographic situations.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

For instance, since AD 1600 , societies have developed in the UK, North America, and Australasia, which clearly share some degree of common history (phylogeny). This is evident in the almost universal use of the English language, in the direct biological ancestry of many inhabitants of these regions from a British source, and in many aspects of material culture which originated in ways of doing things widely current in Britain between approximately AD 1600 and 1850. These societies in North America and Australasia originated historically via a process of colonization and early political control emanating from the British Isles. Similar generalizations can be made about the spread of Iberian culture, language, and biology through much of Central and South America.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is quite obvious that by no means all of the cultural and biological patterning found in these regions is of a circumscribed British (or Spanish, or Portuguese) origin. Indigenous peoples have contributed, as have migrants from other regions. Cross-cultural borrowings abound and occur continuously, forming a network of horizontal transmission, which in this research paper is termed reticulation.

Thus we have two conceptual directions of trans-mission for the elements of both cultural and biological patterning—vertical (phylogenetic or descent-based) and horizontal (reticulative or interaction-based) (Bellwood 1996a, Dewar 1995, Mace and Pagel 1994). Naturally, in a real-life situation such as the modern USA it is impossible to untangle the inherited from the borrowed in an overall sense and to present the results in the form of a statistical statement. To attempt to do so would in any case be futile. These are simply concepts, which allow us to model the formation of cultural patterns through time, essentially to under-stand the main trends of history.

It might seem obvious that cultures at any given time will reflect variation from both ancestral and borrowed sources. But there is one very significant implication of the concept of cultural phylogeny. In those situations where common ancestry is demonstrable for the member units within widely spread entities, such as language families, major religious complexes, or highly specific style repertoires within archeological complexes, we are obliged to infer dispersal of an ancestral configuration (such as a ‘protolanguage’) from a homeland region. This is especially the case where the entities concerned are of very broad extent. Explanations which involve the convergence of genetically unrelated units into a single entity such as a language family do not work in these large scale, sometimes transcontinental, situations which extend beyond the ranges of regional communication networks.

The linkages between phylogeny and dispersal can therefore become extremely important in explanations for particular long-term and large-scale patterns in human prehistory. Any evidence for fairly rapid and far-flung dispersal will obviously militate against an explanation for cultural patterning expressed in terms of gradual evolutionary change at a constant and uniform rate. By its very existence, phylogenetic patterning carries significant implications favoring a punctuated trajectory for cultural evolution, focused on periodic episodes of dispersal and change alternating with trajectories of relative equilibrium (Bell-wood 1996b; Dixon 1997).

It is important in this regard, however, to differentiate between spreads of people, languages, and other aspects of culture. Ethnographic and historical records offer examples of situations where patterns of biological, linguistic, and sociocultural variation do not correlate at all, or correlate only slightly. On the other hand, they can sometimes correlate with almost 100 percent precision, as in the early stages of population expansion into new territories. Whole populations already in situ geographically can adopt new languages and cultural forms through contact-induced change (Ross 1997), whereas at the other extreme whole populations can colonise new territories with closely correlated physical attributes and cultural characteristics.

In terms of human prehistory, it is important to remember the significance of scale. On a small scale, the inhabitants of a village or small river basin could, and indeed have in many historical and ethnographic examples, adopt a new language and undergo genetic change due to intermarriage with members of an outsider, perhaps of higher status, group of people. Ethnic groups can also ‘fuse’ under situations of depopulation or outsider-imposed stress, as has happened very frequently in the period of tribal shrinkage which history offers us in the form of the ‘ethnographic present’ (Atkinson 1989, Moore 1994, Nicolaisen 1977–78).

But, on a much larger scale, a chain-reactive process of language and cultural shift of this kind will not ex-plain why, for instance, related languages are spoken over vast regions of the earth in the form of major language families such as Indo-European, Austronesian or Uto-Aztecan. These language families had reached their outer geographical limits before the beginnings of written history, and no historical processes such as military conquest or mass media per-suasion can hope to explain them. They are records of major human dispersals, spreading foundation languages and archeological cultures. Many undoubtedly owe their existences to population increase and dispersal consequent upon the regional beginnings of agropastoral food production (Renfrew 1997). But this is not true for all, since many languages such as English and Spanish have spread over vast distances in recent historical times and can also be regarded as potential foundation languages for future language families. Comparative linguistics and ethnohistory also reveal some excellent examples of large-scale hunter-gatherer dispersal in the form of the Eskimo-Aleut and Athabaskan language families in North America.

The point to be reinforced is that wherever phylogenetic relationships can be demonstrated to exist between the members of an array of languages or cultures (including archeological cultures), then dispersal of an ancestral complex must be inferred. Whether or not this ancestral dispersal directly related to a movement of actual people is something which must be decided on a case-by-case basis. In the case of extremely widespread phylogenetic entities, population movement to some degree can hardly be denied. In addition, most language families clearly spread relatively quickly in overall chronological terms. From internal evidence and archeological correlations, most reached their geographical limits in 4,000 years or less (for example, between 2,000 and 4,000 years from origin regions to outer limits in the cases of Indo-European and Austronesian). Speed of dispersal, in this regard, relates directly to the intensity of punctuation.

The comparative linguistic record can also provide clear structural evidence for rapid dispersal, especially when the component language subgroups within a family do not share any unique linguistic innovations which allow them to be subgrouped phylogenetically above the individual subgroup level (but still below that of the language family as a whole). ‘Descent trees’ created to show the structure within such language families will be extremely rake-like, rather than tree-like with many successive branches. In such cases, claimed for instance for several of the major Austronesian subgroups of Southeast Asia and the Pacific (Pawley 1999), there is a strong likelihood that the resulting pattern reflects an initial history of very rapid and far-flung dispersal, followed by a formation of independent subgroups, each sharing a common ancestry in the initial dispersal but all reflecting an independent history thereafter.

Direct demonstration of rapid dispersal can also be identified in the archeological record, as for example when a particular aspect of artefact style and decoration too complex to reflect functional selection alone is distributed very widely in a short time. Examples include the Olmec stylistic complex which spread through Mesoamerica after 1250 BC (Sharer and Grove 1989), the Early Neolithic Linearbandkeramik cultural complex which spread through central Europe about 5000 BC (Bogucki 1996), and the Lapita cultural complex with its distinctive and elaborately decorated pottery which spread through the western Pacific about 1000 BC (Kirch 1997). In contextual terms it is apparent that these dispersals of material culture correlated with dispersals of people and perhaps language, even though the nature of the archeological record does not allow this to be stated as more than a logical possibility rather than a demonstrated fact. A parallel with the linguistic diversification of language families from a common source also comes in the archeological record when very widespread complexes such as those mentioned above are followed by a breakdown of widespread homogeneity into regional diversity, this diversity becoming more marked over time.

Finally, reasons for dispersal in any given historical situation are probably knowable, even if they are often heatedly debatable. Clearly it is important to distinguish between populations who dispersed into territories devoid of prior human inhabitants and those who moved into already-settled areas. In both situations the inception of a successful trajectory of dispersion colonization would obviously have required the acquisition of some form of advantage allowing demographic growth and range expansion. In the case of many of the examples discussed above the advantage seems to have been the acquisition of systematic agriculture, but the whole story is of course far more complex. The initial human colonizations of empty continents like Australia (60,000 years ago) and the Americas (15,000 years ago) must also have led to the dispersal of phylogenetically-related languages and cultures, of which some faint traces might still survive in present cultural patterns.

1. Some Examples Of Phylogenetic Studies Of Archeological And Ethnographic Cultures

The ethnographic and archeological records are replete with examples of cross-cultural contact via trade, warfare, and intermarriage, indeed by ‘diffusion’ and gene flow in their many forms. Past humans have been just as interested in communicating with their neighbors, whether as friends or foes, as have recent ones. But evidence that ethnographic and prehistoric cultures form phylogenetic arrays indicative of dispersal is not always so obvious once one moves beyond the evidence from comparative linguistics (Mace and Pagel 1994). Normally, teasing out of the nonlinguistic aspects of the pattern requires attention to details from archaeology and biological anthropology, assisted of course by information from comparative ethnology and, where relevant, historical records and oral tradition (e.g., Flannery and Marcus 1983, Romney 1957).

As a case study, a debate has emerged in recent years amongst anthropological scholars working in the islands of Polynesia. Polynesians form a population of many island societies in the great triangle bounded by Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand, including Tonga and Samoa, with a few additional ‘Polynesian Outliers’ existing to the west amongst the larger islands of Melanesia. That Polynesian languages share a common ancestry is not in doubt, but beyond language the explanations for the Polynesian cultural pattern are more contested. Two recent perspectives on the Polynesians—the ‘phylogenetic’ and the ‘reticulative’—can be counterposed.

The archaeologists Kirch and Green (1987, 2001) have presented Polynesia as a ‘phylogenetic unit’ of closely related cultures, languages, and peoples all sharing a common origin derived from the settlement of the Tongan, Samoan, and other nearby Western Polynesian islands by Lapita populations at about 1000–800 BC. Working from the archeological and linguistic records, Kirch and Green suggest that the Polynesian societies of ethnographic times formed a closely related set in terms of material culture, social organization, biological phenotype, and most importantly, language. Societies so related can be conceived as something akin to the genus of biologists—a group of ‘species’ defined as a group through possession of certain uniquely shared features (synapomorphies in biological terminology). From this perspective, Polynesian societies all share a single origin, and since that period of origin have differentiated due to a wide range of historical processes reflecting both internal change and external contacts with other societies both inside and outside Polynesia. Because Polynesian societies are geographically so clearly bounded by sea, and because archaeology and linguistics lead us to believe that only Polynesians ever inhabited Polynesia prior to European contact, the region obviously lends itself ideally to such a phylogenetically oriented historical perspective.

But not all agree entirely with a phylogenetic perspective. The archaeologists Terrell et al. 1997 (see also Terrell and Welsch 1997) take a tangentially opposed and rather more reticulated viewpoint, pointing out that ancient Pacific Island (including Polynesian) societies were never isolated and would always have maintained some degree of contact between different regions. Virtually all archaeologists would agree with this statement in simple form, because of course the archeological, linguistic, and genetic records carry widespread evidence of trade, borrowing, inter-marriage, and so forth between different island populations. But the reticulative perspective is taken further by Terrell and his colleagues to draw the conclusion that interaction will erase any recognizable traces of cultural phylogeny (see also Moore 1994). For these scholars, the phylogenetic ancestry of cultures is generally unknowable, and thus cannot contribute to an understanding of cultural history. In addition, as they rightly point out:

We need to be wary about thinking that history and diversity in the Pacific can be reduced to a few grand moments of genesis and immigration. (Terrell et al. 1997, p. 175)

The perspective offered in this research paper agrees that a masking of phylogenetic history can occur in cases where actual creolization has taken place, in the form of mixing between two cultural entities of entirely different origin and ancestry. Such intricate mixing on the level of material culture is believed to have occurred, for instance, in some of the Austronesian-and Papuan-speaking societies of lowland New Guinea (Welsch et al. 1992, but see also Roberts et al. 1995 for a contrary view). But when ‘like meets like,’ as would generally have been the case in Polynesia where all cultures shared a recent common origin, then erasure of all traces of phylogenetic relationship becomes much harder to imagine. Even in the case of lowland New Guinea, the fact that the Austronesian and Papuan languages have not in themselves generally become creolized tells us something about the strength of cultural, especially linguistic, transmission through time, and from generation to generation.

2. Future Research Prospects

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, there is widespread interest in the prospects of combining linguistic, archeological, and genetic perspectives on the human past. Elsewhere in the Old World a main supporter of a dialog has been the archeologist Colin Renfrew in his writings on Indo-European languages (Renfrew 1987) and broader macrofamily relation-ships (Renfrew 1992a, 1992b). Renfrew’s position, like that of Bellwood for Austronesian (1996a, 1996b, 1997) and that of geneticist Luca Cavalli-Sforza (Cavalli-Sforza and Cavalli-Sforza 1995) for world populations in general, is that the prehistories of large scale ethnolinguistic populations can be approached from the independent, but overlapping perspectives of genetics, archaeology, and linguistics. The basic model here focuses on a homeland concept, followed by phylogenetic descent to the present through a dispersive sequence involving mainly fissions and divergences, albeit constantly tempered with the results of interpopulation contact. But as Bateman et al. (1990) point out, in discussing the problems of reconciling biological and linguistic phylogenies:

Such phylogenies are likely to be ‘noisy,’ reflecting complicating factors such as hybridisation, the less constrained evolution and competitive displacement among cultural traits, and the fact that the contemporaneity of human gamodemes and languages cannot be assumed. (Bateman et al. 1990, p. 13)

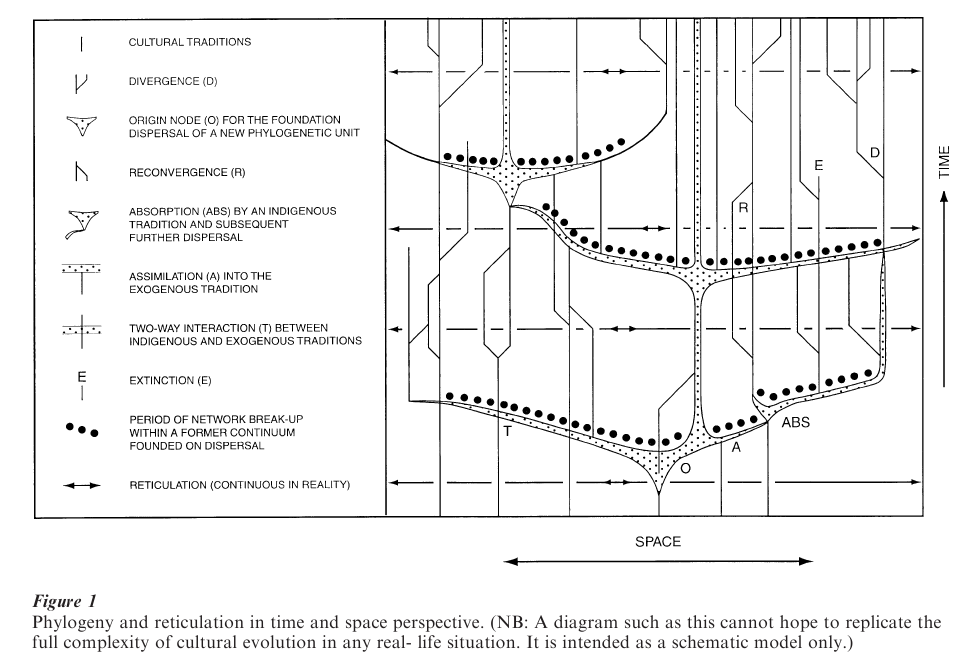

An attempt is made finally to encapsulate some of the cultural trajectories and differing opinions discussed above in the form of Fig. 1. This diagram highlights both divergent and convergent evolutionary situations, which should be regarded as overlapping possibilities rather than as absolutely separate processes. Divergent situations include the following: (a) Cultural divergence following the break-up of a communication network; (b) Large-scale operation of the above as a result of the foundation by dispersal of a new phylogenetic unit (e.g., the dispersal of the foundation dialect chain for a major language family). Situations of convergence or amalgamation include the following: (c) Periodic cultural reconvergence of traditions already related phylogenetically; (d) Absorption of some elements of a cultural dispersal (e.g., language, food production system) by indigenous populations, usually in peripheral locations with respect to the source of the cultural dispersal (i.e., the indigenous dominates the exogenous). Such absorption can then be followed by renewed dispersal; (e) Assimilation with no continuing separate cultural identity of the assimilated tradition (i.e. the exogenous dominates the indigenous); (f) Two-way interaction (the middle road between absorption and assimilation). Also to be taken into account is; (g) Cultural extinction, normally as a result of environmental problems, naturally or humanly stimulated, some-times also reflecting strong assimilation (concepts such as pidgin and creole formation in linguistics are not considered here since they are held to belong mainly to recent episodes of colonial population translocation).

Four other processes are shown schematically in Fig. 1: (a) Generation to generation transmission of cultural traditions through time; (b) Schematic horizontal representation of interaction (reticulation). Reticulation is continuous and universal; (c) The relative potential for population growth (rapid during population dispersal); (d) The period during which the breaking-up of a cultural network, resulting from the foundation dispersal of a future phylogenetic unit, will give rise to separate cultural traditions.

The aim of the diagram is, in part, to indicate that human prehistory cannot be purely regarded as a process of local evolution through all time, but that major episodes of dispersal of the foundation cultures for future phylogenetic arrays punctuate the mesh of gradual reticulate ethnogenesis. Without such dispersals there could be no major language families, and none of the rapid and large-scale spreads of early agricultural economies and cultural complexes which we read from the archeological record in many parts of the world.

Bibliography:

- Atkinson R R 1989 The evolution of ethnicity among the Acholi of Uganda: The precolonial phase. Ethnohistory 36: 19–43

- Bateman R, Goddard I, O’Grady R, Funk V, Mooi R, Kress W, Cannell P 1990 Speaking of forked tongues: The feasibility of reconciling human phylogeny and the history of language. Current Anthropology 31: 1–24

- Bellwood P 1996a Phylogeny and reticulation in prehistory. Antiquity 70: 881–90

- Bellwood P 1996b The origins and spread of agriculture in the Indo-Pacific region. In: Harris D (ed.) The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. UCL Press, London, pp. 465–98

- Bellwood P 1997 Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago, 2nd edn. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, HI

- Bogucki P 1996 The spread of early farming in Europe. American Scientist 84: 242–53

- Boyd R, Richerson P J 1985 Culture and the Evolutionary Process. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Cavalli-Sforza L L, Cavalli-Sforza F 1995 The Great Human Diasporas. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Cavalli-Sforza L L, Feldman M 1981 Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach. Princeton University Press, Princeton, CT

- Dewar R 1995 Of nets and trees: Untangling the reticulate and dendritic in Madagascar’s prehistory. World Archaeology 26: 301–18

- Dixon R M W 1997 The Rise and Fall of Language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Durham W H 1991 Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CT

- Flannery K V, Marcus J 1983 The Cloud People. Academic Press, New York

- Kirch P V 1997 The Lapita Peoples. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Kirch P V, Green R C 1987 History, phylogeny, and evolution in Polynesia. Current Anthropology 28: 431–56

- Kirch P V, Green R C 2001 Hawaiki: Ancestral Polynesia. Cambridge University Press

- Mace R, Pagel M 1994 The comparative method in anthropology. Current Anthropology 35: 549–64

- Moore J H 1994 Putting anthropology back together again: The ethnogenetic critique of cladistic theory. American Anthropologist 96: 925–48

- Nicolaisen I 1977–78 The dynamics of ethnic classification: A case study of the Punan Bah of Sarawak. Folk 19–20: 183–200

- Pawley A K 1999 Chasing rainbows: Implications of the rapid dispersal of Austronesian languages for subgrouping and reconstruction. In: Zeitoun E, Li P J-K (eds.) Selected Papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei, pp. 95–138

- Renfrew C 1987 Archaeology and Language. Jonathan Cape, London

- Renfrew C 1992a Archaeology, genetics, and linguistic diversity. Man (NS) 27: 445–78

- Renfrew C 1992b World languages and human dispersals: A minimalist view. In: Hall J A, Jarvie I C (eds.) Transition to Modernity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 11–68

- Renfrew C 1997 World linguistic diversity and farming dispersals. In: Blench R, Spriggs M (eds.) Archaeology and Language I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations. Routledge, London, pp. 82–90

- Roberts J M, Moore C C, Kimball Romney A 1995 Predicting similarity in material culture among New Guinea villages from propinquity and language: A log-linear approach. Current Anthropology 36: 769–88

- Romney A K 1957 The genetic model and Uto-Aztecan time perspective. Davidson Journal of Anthropology 3: 35–41

- Ross M 1997 Social networks and kinds of speech-community event. In: Blench R, Spriggs M (eds.) Archaeology and Language I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations. Routledge, London, pp. 209–61

- Sharer R, Grove D (eds.) 1989 Regional Perspectives on the Olmec. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Terrell J, Hunt T, Gosden C 1997 The dimensions of social life in the Pacific. Current Anthropology 38: 155–96

- Terrell J, Welsch R 1997 Lapita and the temporal geography of prehistory. Antiquity 71: 548–72

- Welsch R L, Terrell J, Nadolski J A 1992 Language and culture on the North Coast of New Guinea. American Anthropologist 94: 568–600