Sample Culture As Explanation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Culture is a shared interpretive scheme. The subject of this research paper is the process by which culture is created. Without being able to make comparisons, what can be said about culture? The theory to be described began as a method for comparing cultural bias (Douglas 1970). Twenty years later it had become a theory about political change (Thompson et al. 1990), with two explicit assumptions.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Assumption number one: people living together try to control one another. A culture develops in response to the need to persuade and to mobilize opinion; principles have to be argued, justifications advanced, and opposing opinions attacked. For sheer survival an organization depends on its members’ efforts to keep it in being; it would dissolve if there were no will to maintain it. Members of a community put each other under continual pressure to show loyalty and give support. It follows from this that a culture protects and promotes a way of organizing, whether it be a family, a shop, or a kingdom.

Assumption number two: a culture is inherently adversarial (Thompson and Schwartz 1990). A culture grows stronger and more coherent by opposition. In one community there will normally be several cultures self-defined against the others; a progressive culture, a traditionalist culture, a culture of individualism, and no doubt always some members who are just not involved. The researcher needs to trace the alignments in any particular community, know what is at stake, and hear members justifying their own preferences and trying to delegitimate opponents. In any major public policy debate, contending parties tend to align them-selves in opposed cultures. They invoke different theories of justice which fuel their conflict and keep the intercultural struggle alive (Davy 1997).

1. Four Types Of Organization

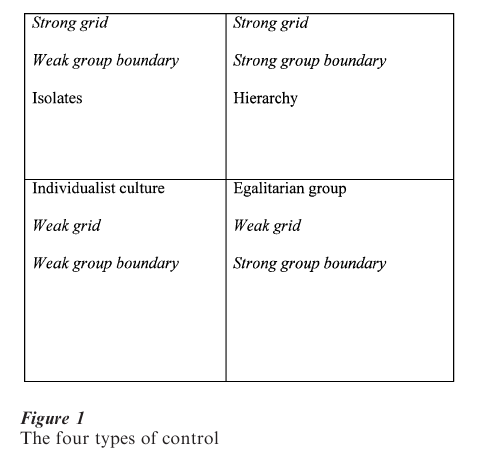

The method provides an abstract model of organizational forms, a spreadsheet on which the biases of a group of human subjects can be located. The scheme is necessarily abstract, since it is intended to apply to any kind of social context or conflict. The intention is to show four incompatible social organizations. It represents a range of social constraints by which individuals are confronted. By choosing to align with one type, the person automatically invites opposition from the others.

Why four types? Because 500, or even 20, would be too difficult to manage. Another answer is that the two axes generate four types well known in Western social science writing, so the number fits well to the con-temporary discourse. Another answer is that four is enough. That is, it is enough for demonstrating the thesis that culture provides a store of justifications which are used to protect or to attack the organization of social life. Another answer is that the four that are shown in Fig. 1 are clearly incompatible with each other. Anyone who uses the scaling possibilities can multiply the number of subtypes at will.

Why are they adversarial? The four cultural types in question are two groups, (complexly structured or unstructured groups), and two cultures of individuals; the culture of individualism, and the isolates. When the principles of their organization are examined, an inevitable rivalry between the four types appears.

2. Hierarchy And Individualism

Different principles of organization make contrary demands on the use of time and space. For example, a hierarchy is organized in complementary-ranked compartments which subordinate the individual member to the whole. Its priorities will be reflected in the grandiose design of public spaces, such as a magnificent cathedral precinct, museum, and municipal park, sheer size contrasting with small individual dwellings stacked in tidy little groups; the pattern of the streets is confusing, new patterns built over the old ones without obliterating them, narrow winding lanes still known by their original names. In the individualist culture, old streets can be torn up to make room for wide, straight motorways, numbered for the sake of efficiency, an overall pattern of grand private mansions and tawdry public places, disorderly hovels. As to the use of time, a hierarchy is not in a hurry, it expects its institutions to last forever, but the individualist culture puts pressure on the use of time as part of its commitment to efficiency. Such incompatible demands uphold the antagonism between these cultures.

To introduce Fig. 1, let us continue to contrast the idea of a hierarchy, quite fairly caricatured in accounts of bureaucracy, with the idea of an individualist culture. Hierarchy assigns status by birth, which gives age, gender, and place as further principles of identification. Hierarchy controls individual behavior and severely limits the scope of negotiations. In the individualist culture, merit, not heredity, determines status, the individualist has to negotiate everything. These are two kinds of organization, one organized by status, in which positions are assigned, the other organized by competition. To map these differences on a graph, start with the horizontal axis (called ‘group’ or ‘group solidarity’). This indicates incorporation into groups. Along that line the individual members of society have to be located according to how much their behavior is controlled by a group boundary. No group belongs at zero on the left corner, an environment favoring individualism, the strong group is towards the right. Some strong groups, such as sects or monasteries, strictly control their boundaries. Else-where, individuals can be members of several groups; a choir, a political club, or a sports club, the local neighborhood watch; none is exclusive, group control is weak, boundaries are weak. It is not difficult to find indices for these features.

3. Four Types Of Control

These are shown in Fig. 1. The two axes combined provide a range of possible social environments. Strong measures for both grid and group correspond to the organization of hierarchy; weak grid and weak group correspond to the environment of an individualist culture.

There are other impersonal constraints that cut across group boundaries, which structure behavior and in this context are referred to as ‘grid’ or ‘structure.’ ‘Grid’ is an impersonal set of rules that prevents free communication and limits transactions, it imposes ceilings on endeavor and barriers to entry. A class system is a grid factor, immigrant status entails restrictions, so does the difference between wealth and its absence. Limitations on the rights of ethnic groups, prohibition on land owning, sumptuary laws, all these draw lines between how members of the same society can transact with each other. Restrictions on nonconformist religions in England used to prevent their access to universities. Such constraints are shown on the vertical axis. The restrictions cited are selective, but others fall on everybody in the community to the same degree; curfews in time of war, restrictions according to age for drinking alcohol, restrictions on road traffic, control of prices or quality of merchandise, health and safety regulations. At the bottom of that vertical line is a possibility of perfect freedom to wheel and deal, at the top, no options.

4. Egalitarian Groups And Isolates

Two corners of the diagram are still not described. One is the relatively rare social environment made by a group which encloses its members within strong boundaries but imposes no structure on them. The one constraint that matters is the external boundary; within it every transaction has to be negotiated. The founding principles of some sects lay down that all the members are free and equal, but in practice it takes a lot of regulation to create perfect equality (Rayner 1988). Where it differs from hierarchy is that this regulation controls all the members in the same way, like rules of the road; it does not create internal divisions.

Environmental or other activist groups as well as religious sects often observe egalitarian ideals. So long as the group is unstructured (a kibbutz, for example), they belong in what is often called (in contradistinction to hierarchy) the sectarian corner of the diagram. Of course, if a group were to maintain a hierarchical system, such as the Mormons or certain groups of environmentalists after having acquired political power, they should be placed along with other hierarchies on the diagram.

There are organizational reasons for why many protesting dissident groups (secular or religious) espouse a doctrine of equality. By withdrawing from the big, complex, mainstream society, the group has problems in maintaining itself. The leaders find they lack authority, they are afraid of being accused of free-riding, decision making becomes difficult. The doctrine of equality is often adopted as a solution, henceforth no-one will be superior to any other member, decisions will depend on consensus. But the solution entails other difficulties. It does not help decision making, or protect authority (Sivan 1995). The group expects to ensure its own survival, but it has no authority to stop its children from leaving. The danger of defection focuses attention on the boundary that defines the insiders. Inside outside becomes the central cultural issue. Then the other cultural traits associated with sectarianism may come into play, a dichotomizing tendency in judgments, the world seen in black and white, outsiders as evil or ungodly, intransigence in negotiation.

The other is the environment of the isolates, drop-out, noncommitted, unaligned individuals. They are by definition not involved when the members of the other three cultures argue strenuously about the right and the good. If they were, they would either have to join up with like-minded souls and be classed as members of a group, or they would have to speak as independents, joining the individualists on the diagram. The diagram shows up well the extreme types of organization, selected on the basis of their incompatibility with the rest. The human subjects have to be fitted into their slots according to agreed measures. Rayner and Gross (1985) have shown how to develop measures with a toy example of a conflict involving a group of environmentalists, town residents, an industrial corporation, and government officials. Theoretically, the four conflicting cultures are potentially available at any time, usually one dominant, each in competition with the others.

5. Information

Group boundaries make a hurdle that new information has to cross. The first test of reliability is the source; insiders are more to be trusted than outsiders, but certain outsiders are privileged. If the group is divided into factions or into administrative compartments, each internal boundary constitutes another barrier.

Blocks to the flow of information abound in a hierarchy; each compartment has its own secrets. It would subvert the structure of the organization to make pressure to disclose records. Knowledge is dispensed according to ‘the need to know.’ Secrecy tends to be acceptable and normal, information is classified and stored systematically. As the organization has institutions for sifting and storing it, information from outside is not automatically unacceptable, but it is put under political scrutiny. Consequently, it travels slowly and often gets stuck.

An egalitarian commune is in worse case, since it lacks any formal structure for testing and classifying the news. Mistrust is the drawback when two strong group cultures try to negotiate with each other; they mishear what the other side is saying. Within an egalitarian group there may be so much mistrust that official envoys to a peace conference may not be fully informed.

Like the culture, information has to compete to be accepted. Individualism is not strong on protecting the commons against spoliation, it justifies its ways on grounds of individual human rights. Information can flow freely in the absence of boundaries, but public institutions for classifying or organizing it are weak. Instead of information there is uninterpreted noise; individuals may have to pay for special knowledge for serious decisions.

The isolates are in a similar pass. Their isolation means that they are not likely to be influential in councils, their news comes to them haphazardly, and they lack incentives to sort it out. They tend to have disconnected, idiosyncratic opinions. It does not matter because in that environment there is no-one else to argue with: they are isolates.

6. Storage And Retrieval

A hierarchy justifies itself by appeal to tradition, and by appeal to the well-being of the whole community. To strengthen its justifications it tends to take its origins back to the beginning of time. Since each subdivision uses the same kind of appeals and justifications as the center, hierarchy develops a characteristic sense of history, extending far into the past, and subdivided at every point that a separate subdivision came into existence. The calendar of feasts revives public memory as it celebrates each point of junction or division. The organization that is strong enough to protect its own security gives guarantees of stability to its members. Assuming the system will endure, they act to assure that it will. Partly because it has no advantage in looking for a sudden end to time, and partly because it is confident enough to allow loans to be repaid over a very long-term future (for example, leased property for 900 years), its sense of future time is also very long.

The individualist culture differs in all these respects. It does not justify itself by reference to history, nor does it regard any of its present ranks or subdivisions as unalterable, so that divisions in past time are not built into the organization. Its festivities are more apt to celebrate individual prowess than past events. Its sense of future time is short. An egalitarian group, by contrast, has no internal divisions whose annual celebrations endow their memories with structure. Their sense of time is millennial; the past will have started apocalyptically with the foundation of the group, the moment which is the point of reference for claims and justifications. Their attacks on outsiders and their justifications of their own record refer constantly to a coming catastrophe for the enemies of the group. The difficulties of organization invite covert competition for leadership; as there is a deficit of power, there are no grades for downgrading, no regular system of punishment, conflicts can only be solved by expulsion or by splitting the group. These structural weaknesses mean that though the movement may have its roots in a long-distant past, each community is relatively new: its history is short.

The fourth cultural type, the isolates, gives mini-mum opportunity for negotiation, either because of demographic sparsity (nobody to negotiate with), or because other people have restricted their freedom to negotiate, typically in the lower echelons of a big bureaucracy. The culture of isolates is politically apathetic, and limited to the short term. While the isolates themselves are not necessarily unhappy, their sense of a communal past is practically non-existent, and such individuals have little in the way of public benchmarks to help in remembering their private pasts.

In this perspective, only the hierarchy has the possibility of recalling a differentiated past with many twists and turnings, but it is certain that its history will be strongly biased in favor of itself.

7. Decision Making

Hierarchy’s characteristic decision procedure is based on historical precedent and seniority. What is once decided can be made effective because the system protects authority. Individualist culture is also effec-tive in decision making, because it reflects the balance of power at the time. By contrast, decision making in an egalitarian community is beset with difficulties; authority is weak and the group risks destruction from its own internal dissension. The isolates, knowing that they have no influence, realistically adopt a culture of fatalism, which militates against consistent decisions.

8. Conclusion

We could introduce the theory from almost any situation of conflict, but we have chosen to focus on selection of information, because, after all, it is about argument and disagreement on values. It can explain why information does not always travel, and how it sometimes gets blocked. Some cultures preserve in-formation about a long historical past, some have a store of techniques for projecting the future, others live in the present and are not interested in the past or the future. The variation is due to the way that organizations act as filters and pointers (Douglas 1987). These examples illustrate how this type of analysis can trace different sources of failure to mobilize support for a given set of principles. It has been widely applied to disagreements about risk. In the late 1990s the scope has widened to include environmental politics of the great waterways, the Ganges and the Rhine (Gyawali 1998, Verweij 2000), traffic control in city planning (Hendriks 1999), conflict in recent British Labour party history (Bale 1999), kinds of control used in public administration (Hood 1998), and even to conflicting ideas about personal privacy (Perri 1998), and market research (Karmasin and Karmasin 1997).

Culture sets up the terms on which individual calculations of interest are based. Organization entails coordination, which entails classification and logic. As they responsibly calculate and negotiate, the rational beings are creating, changing, or sustaining their culture. The method is sometimes criticized for focusing on organizations and paying too little attention to the role of individuals in shaping culture, but far from neglecting the individual, the theory sets the individual person in a normal framework of interaction. At center stage, each rational person, assumed to be interested in the costs or benefits of subscribing to other people’s opinions, is partaking in a process of collective choice.

Bibliography:

- Bale T 1999 Sacred Cows and Commonsense: The Symbolic Statecraft and Political Culture of the British Labour Party. Gower, Ashgate, UK

- Davy B 1997 Essential Injustice, When Legal Institutions Cannot Resolve Environmental and Land Use Disputes. Springer, New York

- Douglas M 1970 Natural Symbols. Penguin

- Douglas M 1987 How Institutions Think. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, NY

- Douglas M, Wildavsky A 1983 Risk and Culture, an Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers. University of California Press, CA

- Gyawali D 1998 Patna, Delhi and environmental activism: Institutional forces behind water conflict in Bihar. Water Nepal 6(1): 67–115

- Hendriks F 1999 Public Policy and Political Institutions, the Role of Culture in Traffic Policy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK

- Karmasin H, Karmasin M 1997 Cultural Theory, Ein Neuer Ansatz fur Kommunikation. Marketing und Management, Austria

- Perri 1998 The Future of Privacy. Demos, London

- Rayner S 1998 The rules that make us equal. In: Flanagan J G, Rayner S (eds.) Rules, Decisions and Inequalities in Egalitarian Societies. Avebury, pp. 20–42

- Rayner S, Gross J 1985 Measuring Culture. Columbia University Press, New York

- Rayner S, Malone E 1998 Human Choice and Global Climate Change. Battelle Institute, Columbus, OH

- Sivan E 1995 The enclave culture. In: Marty M (ed.) Fundamentalism Comprehended. Chicago University Press, Chicago, pp. 11–68

- Thompson M, Schwartz M 1990 Divided We Stand, Redefining Politics, Technology and Social Choice. Harvester Wheatsheaf

- Thompson M, Ellis R, Wildavsky A 1990 Cultural Theory. Westview, Boulder, CO

- Verweij M 2000 Transboundary Environmental Problems and Cultural Theory, the Environmental Protection of the Rhine and the Great Lakes. Berghahn, London