This sample culture research paper on aggression and culture features: 4500 words (approx. 15 pages) and a bibliography with 14 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Abstract

This research paper conceptualizes aggression as coercive forms of social control, perceived as being applied illegitimately. Mundane social control is exercised through role prescriptions and is routinely met with compliance. Whenever social control is perceived to be exercised illegitimately, however, victims and their representatives respond to restore interpersonal and social order. That response may be retaliatory coercion. The type of response elicited will be shaped by personal factors such as the emotionality of the victim and the hedonic relevance of the anti-normative action; target factors such as the gender, status, and ethnicity of the perpetrator; social factors such as the degree of interpersonal support for retaliation or harmonizing; historical factors such as the strength of antagonistic ideologies among ethnic groups; economic factors such as the degree of relative inequality between the actors and between their social groups; and cultural factors such as the presence of honor or restraint codes. For the purpose of understanding aggression, culture may be understood as that complex set of external conditions that sustains or retards the development of those social psychological conditions that predispose toward interpersonal violence. This research paper elaborates these societal conditions and their psychological imprints on social actors.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Outline

- Culture and Aggression: Contexts for Exercising Coercive Control

- Culture as Contexts for Influence

- Holocultural Studies of Aggression

- Culture and Studies of Aggression in Individuals

1. Culture and Aggression: Contexts For Exercising Coercive Control

Cultures may be construed as ecological–social contexts that promote or restrain acts of interpersonal or intergroup control. These acts function to influence other persons or the groups they constitute to provide resources desired by the influencing agent while minimizing the costs required for their acquisition. The party being influenced is also acting to maximize benefits and minimize costs while engaged in this dance of interdependencies. So long as this exchange of influence proceeds within normatively accepted guidelines, the process is regarded as an acceptable negotiation. Once one of the parties violates the other’s norms of acceptable procedure or outcome, the other’s influence attempts may shift and become more coercive.

Coercion in influence is characterized by the use of punishments or by the withholding of rewards from the target as a consequence of his or her behavior. It is these tactics of contingent control that are closely monitored in society because their use may violate social norms for exercising social influence over another’s interests. Any escalation in the strength of influence tactics will typically be construed as intended by the other party but unethical, illegitimate, unjustified, savage, immoral, or wrong and will typically be met with a counterattack. One party triumphs, at least in the short term, leaving the other party subjugated and resentful, immobilized and hopeless, or dead and past harboring plans for revenge. Harmony or at least a working truce may be restored between these interdependent parties. If that harmony has not been restored in ways that satisfy the aggrieved parties, however, memories of unrequited abuse will fester, motivating acts of revenge for past wrongdoings. These acts of retaliation may erupt if the social calculus shifts through changes in the balance of power, economic recession, environmental degradation, and the like.

In the course of this familiar drama, the label ‘‘aggressive’’ will often be deployed to describe antinormative tactics of influence exercised by the other party. In general, such acts result in physical or material harm to the other party, such as wounding or removal of possessions, but can also include symbolic impositions, such as insults or threats. However, these same acts are generally not construed as aggressive by those who perform them. Such dramatically different accounts of hurtful acts given by perpetrators and by victims have been well documented. Instead, if called to account by an accepted authority, ‘‘aggressors’’ will justify their use of coercive control in terms of self-defense, doing their job, retaliating for past injustices—that is, getting even; serving their group, organization, or nation; protecting the social order; and the like. Aggression, then, is not a characteristic of the action itself but rather a labeling process arising out of the social context within which it occurs. That label constitutes a disapproving judgment passed on the process by which social influence over another person is exercised. Homicide, robbery, rape, and assault are universally regarded as acts of aggression. Defending oneself against attack, performing painful surgery, executing a convicted rapist, and spanking a disobedient child are generally not so regarded because those acts are often socially approved.

Of course, the exercise of illegitimate tactics of control does not always result in retaliation by the aggrieved party. The target may instead undertake proxy control, influencing third parties—be they friends, family, or social authorities—to restrain, distract, or attack the ‘‘aggressor.’’ Or recipients of such resented manipulation may withdraw from the relationship if an exit option is possible and if alternative relationships providing the same desired goals are available. Alternatively, they may accept such ‘‘alter casting’’ into a subordinate status, thereby acceding to a relationship in which the dominant party may exercise such tactics of control.

The use of any such response to counternormative control depends on the skills and resources available to the target. The target must be aware of alternative responses because not everyone has the social training and intelligence to appreciate alternatives other than retaliation. The target must be willing to use the alternative responses because some may be proscribed by socialization or normatively sanctioned by proximal social groups. The target must be able to mobilize the personal resources and the social agents necessary to exercise that form of influence because not everyone commands the required talents, time, energy, resources, and social credits with others to motivate their intervention.

2. Culture As Contexts For Influence

Culture is a polysemous construct of kaleidoscopic richness, variously defined by practitioners of different social sciences. It may be defined for purposes of doing psychology as a set of ecological–social constraints and affordances potentiating some behaviors, retarding others, or even rendering them irrelevant. This general psychological definition culture was elaborated by Bond as a shared system of beliefs (what is true), values (what is important), expectations, especially about scripted behavioral sequences, and behavior meanings (what is implied by engaging in a given action) developed by a group over time to provide the requirements of living (food and water, protection against the elements, security, belonging, social appreciation, and the exercise of one’s skills) in a particular geographical niche. This shared system enhances communication of meaning and coordination of actions among a culture’s members by reducing uncertainty and anxiety through making its members’ behavior predictable, understandable, and valuable.

This definition focuses on the socialized psychological ‘‘software’’ constituting the operating system for functional membership in a group setting. That group may be any social unit—a family, a work group, an organization, a profession, a caste, a social class, a political state, and the like. The preceding definition is silent about the characteristics of those social units that predispose toward the development of different types and levels of the shared software called culture. Nor does this definition focus on the types and levels of behavior likely to characterize that social unit and its members. It is precisely those contexts and consequences of culture that need to be elaborated whenever one addresses the link between culture and any behavioral outcome such as aggression.

The cultural factors relevant for explaining differences in aggressive behavior will depend on how aggression has been conceptualized. These factors would then be linked to mediating processes responsible for driving aggressive behaviors. Given the preceding discussion, relevant considerations for a cultural analysis would include institutional supports enforcing procedural norms for coordinating action and for dividing resources; norms about the legitimacy of claims made by outsiders or different others on one’s resources, including ideologies of antagonism and social representations of a group’s history, focused on specific out-groups and their members; direct or indirect socialization for coercive responses to particular targets (e.g., women, the disabled, other lower status persons); training provisions and social support for conflict resolution strategies other than retaliation; the goals that social group members hold about desirable material and social outcomes and the procedures for achieving those outcomes (i.e., their instrumental and terminal values); attitudes held by citizens about the proper place of out-groups (i.e., social dominance orientation); and beliefs about the efficacy of various influence tactics, citizen neuroticism, and emotionality affecting impulse regulation. Each of these mediators is made salient in the issue of culture’s relation to aggression by its hypothesized role in eliciting coercive tactics of interpersonal and social control. Whether a person or group using such coercive violent means of social control would be perceived as behaving aggressively would depend on the position of the actor and the target in the social order of their culture.

3. Holocultural Studies Of Aggression

Dramatic and universally accepted acts of aggression, such as homicide and political violence, can be studied only at the level of larger social units, such as societies and nations, because their incidence is either rare or group encompassing. Such studies are called ‘‘holocultural’’ because they involve social units sampled from the whole range of the earth’s cultures. Aggressionrelevant data on larger social units are easier to obtain than are individual-level data on cross-cultural comparisons of coercive control. Perhaps this is one reason why there is so little comparative psychological work on aggression despite its social importance. The problem with holocultural studies, however, is that it is more difficult to extract defensible social psychological explanations for their results.

3.1. Waging War and Internal Political Violence

In 1994, Ember and Ember examined the ethnographic atlas for clues about the causes of war in 186 societies. They concluded that societies wage war due to recurrent natural disasters that rendered them vulnerable to food shortages: ‘‘Fear of such unpredictable shortages will motivate people to go to war to take resources from others in order to protect against resource uncertainty.’’ The societies they studied were smaller than current nation-states, which are enmeshed in relations of trade interdependence and protected by mutual defense pacts. These state-level connections act to restrain war, although the driving force of resource acquisition remains a powerful incentive for waging war. Looming environmental disasters, with their potential for reducing current national resources such as arable land and potable water, argue for carefully coordinated international programs of disaster relief and foreign aid. In their absence, pressures for waging war will mount as some nations suffer reversals of fortune.

In 1988, Rummel assessed war making during the course of the 20th century. He concluded that the historical record shows that democratic political systems—that is, ‘‘those that maximize and guarantee individual freedom’’—are less likely to engage in war. Rummel argued that ‘‘there is a consistent and significant, but low, negative correlation between democracies and collective violence’’ and further that ‘‘when two nations are stable democracies, no wars occur between them.’’ Rummel argued that this relationship is causal and not merely correlational, stating that a democracy ‘‘promotes a social field, cross-pressures, and political responsibility; it promotes pluralism, diversity, and groups that have a stake in peace.’’ Institutional pressures and supports in a democracy, from the opportunity to vote anonymously to legal supports for human rights, lead to the development of psychological processes, such as egalitarian values and trust in others, that prevent political leaders from mobilizing the mass support required for waging war. The same argument applies to restraining internal political violence. In this regard, Rummel provided this sobering reminder:

War is not the most deadly form of violence. Indeed, while 36 million people have been killed in battle in all foreign and domestic wars in our century, at least 119 million more have been killed by government genocide, massacres, and other mass killing. And about 115 million of these were killed by totalitarian governments (as many as 95 million by communist ones).

He hastened to point out that during the 20th century ‘‘there is no case of democracies killing en masse their own citizens.’’

The preceding discussion suggests that if the big picture on aggression is considered, concerted efforts toward educating populaces for effective democratic citizenship would be the most powerful prophylactic against violence and investment in social capital that the leaders of a nation could make. Of course, the courage and insight required for nondemocratically installed leaders to commit the resources necessary for this task and imperil their own power basis will be hard to find without external political influence being engaged.

3.2. Homicide

The most reliable data on levels of homicide in a social unit are provided by the standardized measures collected by the World Health Organization, although judgments of homicide levels in a society have also been taken from the anthropological record provided by the Human Relations Area Files. These homicide levels are typically correlated with societal factors to provide insights about characteristics of social systems that predispose members of their citizenry toward lethal aggression against one another. Such findings are springboards for some social psychological explanation of violence by citizens against fellow citizens. Occasionally, empirical data are provided to support such speculations about social psychological processes mediating these acts of violence.

3.2.1. Societal Factors

Most research in this area is bivariate, where one societal predictor, such as national wealth, is correlated with the rate of national homicide. Over time, a number of societal factors have been advanced as ‘‘causing’’ higher levels of internal murder. Theory is then advanced to explain each variable’s avenue of influence. One problem with this piecemeal approach is that many of these factors are interrelated and their avenues of influence are overlapping or perhaps identical. Understanding the full range of societal relations to homicide rate requires multivariate studies where a host of potential societal predictors is deployed, so that their separate influences may be assessed. Such studies could then confirm many of the past findings, integrating theorizing around key processes such as social trust. It could also add new predictors to the societal equation, suggesting further lines of theoretical development.

It is possible to use these fewer multivariate studies to integrate the results from the various studies that have been conducted on homicide rates over the past 40 years. Using this approach, the following societal variables have been linked to homicide rate: a society’s recent history of waging war, its level of wealth (negatively), its degree of economic inequality, its percentage of male unemployment, its strength of human rights observance (negative), and a measure of male dominance themes in its national system (labeled ‘‘female purity’’). More studies have been conducted using the readily available economic indexes, so one can be more confident in their robustness of impact, especially that of relative inequality. The other variables are new entrants in the predictive arena, emerging as more national indicators become available for use by social scientists during the 21st century.

3.2.2. Social Psychological Mechanisms

Investigators of societal variables related to homicide have often used their empirical results to support the probable operation of certain social psychological processes in potentiating homicide. So, for example, Wilkinson argued in 1996 that relative economic inequality predisposes the ‘‘have-nots’’ in a social system to feel routinely status deprived and inferior. The social stress so induced increases the likelihood of violent behavior in everyday social exchanges. Taking a complementary approach, Fukuyama argued in 1995 that the higher levels of incivility, including homicide, in poorer societies arise through lower levels of social trust held by citizens in such polities. This higher ambient trust among a society’s members may be sustained by greater equality in resource distribution because the two features of a social system are highly correlated.

In their 1994 analysis, Ember and Ember did more than speculate on the social psychological processes involved in homicide; they empirically demonstrated that the societal link between a recent history of warfare and a society’s internal homicide rate is mediated by the stronger socialization of males for aggression in such societies. This demonstration is accomplished by using regression techniques that enable the interrelatedness of societal and social psychological variables as predictors of homicide to be assessed within the same data set. The richness of the linkages so revealed, however, depends on the types of social psychological variables included in the data set and their overlap with the nations whose homicide rates are being studied. Because these data sets consist of nation scores, considerable data collection must be undertaken to provide the necessary number of ‘‘citizen’’ averages on the social psychological predictors. This multicultural database is becoming more and more available with the increasing activity in cross-cultural psychology, so the linking of societal factors to psychological dispositions of a citizenry to national rates of violent outcomes is becoming possible.

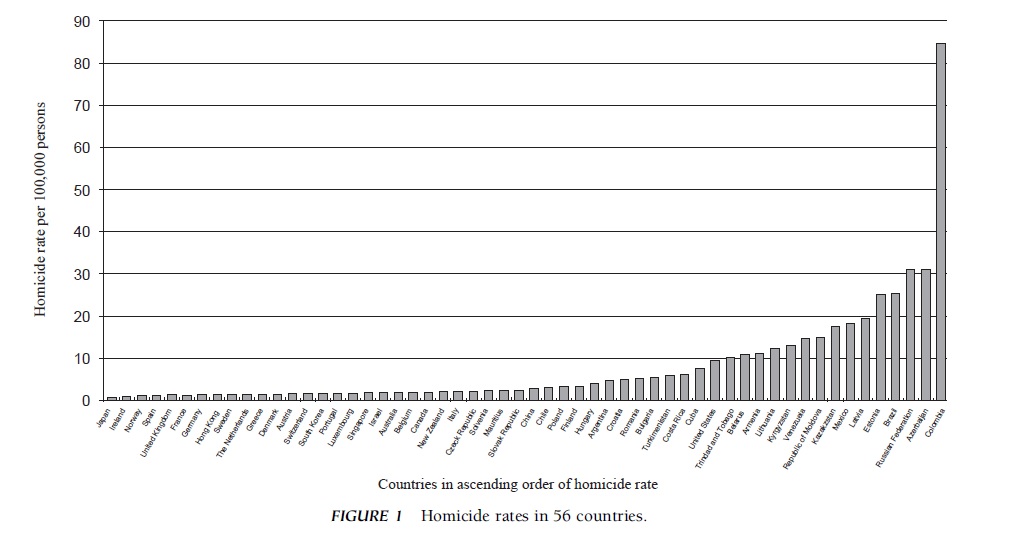

Using one such database, Lim and colleagues found that national rates of homicide across 56 nations were jointly predicted by a nation’s level of economic inequality, its gross national product (GNP) growth over a decade (negative), and its emphasis on female purity (Fig. 1). This finding confirmed the results of many previous studies of economic inequality and homicide but extended them to include additional societal predictors of internal violence. Lim and colleagues also found that citizen scores on the psychological constructs of belief in fate control and the length of typical emotional experiences predicted national rates of homicide. Using regression techniques, they concluded that the effect of female purity was mediated by citizen endorsement of fate control, that is, the belief that one’s outcomes were shaped by one’s predetermined destiny. This linkage led to speculation that in societies characterized by social divisions and rigidity of social structure, parents typically socialize their children for responsiveness to external control rather than for internal self-regulation. Lacking strategies for internally generated self-control, citizens in such societies are more likely to respond with homicide to the universal frustrations arising out of mundane interpersonal interdependencies.

In nations where citizens routinely experience emotions for longer periods of time, there would be a persistence of emotionality into more of one’s daily interactions with others. This wider reach of emotionality would amplify whatever dominant tendencies characterized a particular exchange. It is easy to understand how, if that exchange involved coercive control or resistance to its imposition, the frequency of homicide as one extreme outcome would be higher in such countries.

Such conclusions are speculative because they are drawn from correlations of national-level scores. In the case of homicide, however, there is little choice but to use data from large social units. The plausibility of the conclusions drawn will depend on their connectability to theory and empirical data derived from analyses of individual behaviors related to homicide. For example, a person’s capacity for self-regulation has been linked longitudinally to lower frequencies of antisocial acting out. So, it is plausible that belief in control by fate is part of a personality constellation related to poor impulse control. Psychological studies of individuals differing in their beliefs about fate control will be necessary, however, to strengthen the plausibility that citizen differences in fate control link to national homicide rates through the agency of impulse regulation.

4. Culture and Studies of Aggression in Individuals

The holocultural studies discussed previously alert social scientists to the need for validated theories about the psychological mechanisms involved in generating violent behavior against others. These mechanisms must be measurable across cultural systems, and their role in potentiating harm to others must be demonstrated empirically. This is the mandate for cross-cultural psychology, but its offerings are remarkably scanty. In part, this shortfall arises due to the definitional problems noted earlier (e.g., what behaviors other than homicide, rape, or physical assault constitute aggression?) There are a plethora of American laboratory studies, for example, that use paradigms such as the teacher–learner shock scenario to examine aggression. In such a setup, the participant-teacher trains her confederate-student under various experimental conditions hypothesized to provoke higher levels of hostility (e.g., ambient temperature, expectation of future interaction, prior insult by the confederate-student). This procedure, however, fails to engage the dynamics of aggression as anti-normative behavior because the experimenter has explicitly legitimized the delivery of noxious stimuli to the student as an educational exercise. Other experimental scenarios for studying aggression and its facilitating conditions likewise encounter the same problem of its implicit legitimation by the experimenter.

A related problem for the cross-cultural laboratory study of aggression involves the meaning of the exchange between the two parties created by the experimenter. In the teacher–learner scenario, one could imagine that in more hierarchical cultures with a tradition of corporal punishment in classrooms, the legitimation of hurtful behavior by the experimenter would appear to be more acceptable to the participant teacher. The confederate-student would then receive even higher levels of shock for a given set of experimental conditions. One could not, however, conclude that persons of this hierarchical culture were more aggressive given that local understanding of the shocking behavior is so different in the new culture.

Given these conceptual problems, two ways forward have been tried. One approach across cultural groups involves the use of scenario studies where cultural informants are presented with descriptions of behavioral exchanges between persons and are asked to make judgments about these exchanges and the persons involved. Knowledge about the cultures can then be used to predict the outcomes of these judgments. So, for example, Bond argued that in a more hierarchical culture, a direct coercive tactic of influence in a business meeting would be construed differently than it would in an egalitarian culture, depending on its source. As predicted, a superior insulting a subordinate was less sanctioned in Chinese culture than in American culture, and a subordinate in Chinese culture was more strongly sanctioned for insulting a superior than was a subordinate in American culture for insulting a superior. Similarly, knowledge about cultural dynamics can be used to predict the frequency and judged effectiveness of direct coercive tactics of influence, depending on their source and their relationship with the target. In such studies, the behavior being judged is the same, and its different meaning is examined in light of different cultural dynamics. The perceived aggressiveness of the behavior and the sanctions it receives vary as a function of these dynamics.

The second approach involves observation of hostile behavior in common settings such as prisons and schools. These observational studies are time-consuming and require agreement on what behaviors to measure. There has been considerable debate across participants in the European Union, for example, as to what behaviors constitute ‘‘bullying,’’ so that cross-national comparisons can proceed. Typically, a ‘‘least common denominator’’ position that includes only physical or verbal provocation between perpetrator and victim is adopted. Other indirect forms of bullying, such as gossiping and cliquing against others, are excluded. This happens in part because persons from different cultural traditions might not regard these behaviors as bullying, but also because the indirect behaviors are extremely difficult to measure reliably. Given all of these concerns, few cross-cultural studies involving in situ measures of behavior have been conducted to date.

Less conceptual and measurement difficulty is encountered when behaviors are measured by asking knowledgeable observers, such as parents and teachers, to rate the frequency with which their charges engage in aggressive behaviors. Chang, for example, employed a 7-item scale measure of aggressive behaviors such as hitting, teasing, and shoving others. The scale forms a coherent single measure of aggressiveness, and independent observers of a given pupil rate that pupil’s aggressiveness with high degrees of agreement. It would be easy to examine this measure in other cultural contexts for its equivalence, adding or subtracting behaviors until a comparable measure of pupil aggressiveness is achieved. Cultural groups could then be compared for their levels of aggressiveness.

There is a slowly growing body of cross-cultural research using the scenario and behavior-reporting approaches. The problem with this work is that it is often only descriptive, reporting the cultural differences and perhaps speculating why they occur. There is little theory-driven work that measures the processes hypothesized to drive the aggressive behavior in the cultural groups studied. One exception is a recent study by Chow and colleagues using recollections by cultural informants of upsetting interpersonal events. They argued that everyday aggressive behavior often emerges out of social exchanges where one party harms another party, resulting in retaliation from the aggrieved party. Self-reports of behaviors undertaken by the victim after the harm doing indicated an equivalent cluster of assertive or aggressive behaviors in both Japanese and American informants. This assertive counterattack is driven by psychological factors uniting to generate a motive to retaliate and by social factors relevant to the relationship such as the gender of the two parties and their degree of familiarity.

Chow and colleagues found that both internal psychological and external social factors contributed toward assertive counterattack in both Japanese and American cultures but that psychological factors weighed more heavily than social factors for the Americans than for the Japanese. This finding confirmed theoretical speculation that collectivists, such as Japanese, are more responsive to external forces, whereas individualists, such as Americans, are more responsive to internal forces. This reasoning was supported by personality measures of individualism that predicted the tendency to emphasize psychological factors more than social factors in directing one’s retaliation against the harm doer. Controlling for the level of harm experienced, the investigators found that Americans were more likely to counterattack assertively because their motivation to retaliate was greater than was the Japanese motivation.

The next step in such research on culture and aggression is to examine why the motivation of any cultural group to counter any harm with coercive retaliation is greater than that of another cultural group. One strong possibility is the experience of harsh parenting. Punitive parents model coercive strategies of control as they manage their children, indirectly teaching children to respond to interpersonal frustration with confrontational assertiveness. This linkage between harsh parenting and children’s aggressiveness has been confirmed in other settings such as school. Such studies have provided the inspiration for successful intervention studies that reduce the level of child aggression through programs teaching parents to intervene nonviolently.

Chang further discovered that some of the linkage between harsh parenting and child aggression is mediated by lower levels of affect regulation characterizing those pupils who act out. Such internal dispositions may be higher in citizens of some cultural groups than in citizens of other cultural groups due to differential socialization styles and procedures. The different strengths of these aggression-related attributes could then account for observed cultural differences in aggressive responding. Other possible internal mediators include well-studied psychological dispositions such as self-regulatory efficacy, sociopathy, and state anger. Social psychological factors varying across cultures could include orientation toward confrontation, honor sensitivity among males, degree of ethnic identification, social support for retributive as opposed to restorative procedures of justice, and socialization into ideologies of antagonism and indebtedness.

Higher cultural levels of these psychological and relational dispositions may be the legacy of cultural circumstances (e.g., a history of war, tribal conflict, or colonialism), a herding economy, slavery, or internal political violence, any of which may lead parents to socialize their children to inflict harm on others as a way of solving problems in interpersonal and intergroup coordination. As indicated earlier in the discussion of holocultural studies, psychologists have some ideas about what these cultural circumstances might be. But they need to conduct the sort of theory-driven and empirically validated research necessary to substantiate their speculations about how culture operates to affect aggression. Psychologists must instrument the hypothesized dispositions, measure them in persons, and then observe their behavior when dealing with interpersonal and intergroup relationships. Who chooses cooperation and consensus? Who chooses confrontation and conflict? How then can life be enhanced by encouraging social systems to socialize their citizens for the former rather than for the latter?

Bibliography:

- Bond, M. H. (2004). Culture and aggression: From context to coercion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 62–78.

- Chang, L. (2002). Emotion regulation as a mediator of the effect of harsh parenting on child aggression: Evidence from mothers and fathers and sons and daughters. Unpublished manuscript, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Chow, H., Bond, M. H., Quigley, B., Ohbuchi, K., & Tedeschi, J. T. (2002). Understanding responses to being hurt by another in Japan and the United States. Unpublished manuscript, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Dishion, T. J., Patterson, R., & Kavanagh, K. (1992). An experimental study of the coercion model: Linking theory, intervention, and measurement. In J. McCord, & R. Trembley (Eds.), The interaction of theory and practice: Experimental studies of interventions (pp. 253–282). New York: Guilford.

- Ember, C. R., & Ember, M. (1994). War, socialization, and interpersonal violence: A cross-cultural Journal of Conflict Resolution, 38, 620–646.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Lim, F., Bond, M. H., & Bond, M. K. (2002). Social and psychological predictors of homicide rates across nations: Linking societal and dispositional factors. Unpublished Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Rummel, R. J. (1988, June). Political systems, violence, and war. Paper presented at the S. Institute of Peace Conference, Airlie, VA. (Available: www.shadeslanding.com)

- Segall, M. H., Ember, C. R., & Ember, M. (1997). Aggression, crime, and In J. W. Berry, M. H. Segall, & C. Kagitcibasi (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 213–254). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Sidanius, J. (1993). The psychology of group conflict and the dynamics of oppression: A social dominance In W. McGuire, & S. Iyengar (Eds.), Current approaches to political psychology (pp. 183–219). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Staub, E. (1989). The roots of evil. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Tedeschi, J. T., & Bond, M. H. (2001). Aversive behavior and aggression in cross-cultural In R. Kowalski (Ed.), Behaving badly: Aversive behaviors in interpersonal relationships (pp. 257–293). Washington, DC: APA Books.

- Tedeschi, J. T., & Felson, R. B. (1994). Violence, aggression, and coercive actions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Wilkinson, R. G. (1996). Unhealthy societies: The afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge.