Sample Religion And Social Control Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In most societies at most times religion has been the key institution devoted to answering three of the fundamental questions human beings have posed, namely, ‘How and why were the universe, life and humankind created?,’ ‘What moral rules should we follow in order to lead good lives?,’ and ‘What becomes of us after we die?.’ Most of the great world religions have answered the three questions together as part of a single coherent narrative. With some religions a just and righteous God was said to have created the world and its inhabitants, communicated moral decrees to them by revelation, and would after their deaths sit in judgment on them and assign them to paradise or to hell according to whether or not they had obeyed these precepts. Other religions held that the sum of an individual’s good and bad deeds in this and previous lives would determine the nature of a reincarnation after their death according to the law of karma (Davies 1999). Clearly, beliefs and institutions of such fundamental significance are of great importance for social control. As Professor A G N Flew (1987, p. 71), the distinguished philosopher of religion, has noted:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Can we not understand the hopes of the warriors of Allah who expect if they die in Holy Wars to go straight to the arms of the black-eyed houris in paradise? Can we not understand the fears of the slum mother kept from the contraceptive clinic by her priest’s warning of penalties for those who die in mortal sin? Of course we can: they both expect—and what could be more intelligible than this?—that, if they do certain things, then they will in consequence enjoy or suffer in the future certain rewards or punishments.

The nature of the social control thus exercised varies greatly from one society to another, as does the degree to which emphasis is placed (a) on social conformity as part of the natural order of things, (b) on establishing, monitoring, and controlling the nature and content of an individual’s conscience, or (c) on claiming to be able to affect or at least to predict a person’s fate after death.

Sometimes these forms of social control have simply reinforced other forms of power available to the secular rulers of a society, as when these rulers have also been the key religious authorities or the two groups have been closely allied. Likewise, resistance to the ruler might well be reinforced by religious dissent (Martin 1978) but with the caveat that the degree of social control that the dissenting group, whether the seventeenth century English upholders of the Cromwellian Commonwealth, the Roman Catholic exercisers of a moral monopoly in Ireland (Inglis 1998), or the Sikhs of the Punjab, exerts over its members may be exceptionally high.

Religion can, of course, be an independent source of power and social control, sometimes exercised over matters that are of little interest to the secular authorities. The medieval Roman Catholic Church’s forbidding of marriages between cousins up to the sixth degree or the refusal of the Greek Orthodox Church to permit a person to marry a fourth time after the deaths of three spouses were forms of social control that were at times a nuisance to the rulers of the relevant societies, who were concerned mainly with forming dynastic alliances and producing male heirs. They were part of a set of independent social controls exercised through these churches’ monopoly over the creation and dissolution of marriages, and hence over sexuality, reproduction, legitimacy, and inheritance, i.e., over crucial aspects of not only personal but also material and political life.

This form of social control may be seen as what Polanyi (1951) has termed deliberate or corporate order comparable to, say, a centrally planned economy, statute law, or the internal workings of a private bureaucracy. In each case there are, of course, divisions of interest, contested areas of authority, and competition between individuals and sectors using the exploitation and interpretation of rules to enhance power, but in principle there is a hierarchical system that may not be contested beyond a certain point. Rome has spoken, the matter is closed and the Brahmins alone can determine a caste’s pedigree and thus influence its position in a hierarchy of purity of which they are the apex (Dumont 1970). Yet in all cases in traditional societies, most social control would have been local. Violence, theft, or sex with other men’s wives would be kept in check by local opinion in one’s village, mir, mura, jati, or kinship group rather than the direct use of priestly authority, the threat of divine wrath, or the dread of hellfire or of reincarnation as a scavenging dog. A mixture of respect for and fear of local chiefs, landowners, or state officials will also have played a part. Religion was just one part, though an important part, of local social control. Beneath the designed order lay a myriad local communities held together by an alternative form of order, the interactive order of face-to-face communities, the essence of Gemeinschaft.

Polanyi (1951) contrasts deliberate or planned order with spontaneous order which can be observed wherever stable arrangements evolve as a result of a large number of independent but interconnected decisions, as with the operation of markets through the price mechanism, systems of common law based on cumulative precedence, or scientific progress through conjecture, experiment, refutation, and provisional confirmation. No one directs or designs these large, widely dispersed, flexible, and responsive instances of spontaneous order, yet they are much superior in their efficacy to most attempts to create a centrally controlled designed order. Their equivalent in religious terms and one with a crucial importance for social control may be seen in the flourishing of Protestant sects and denominations, and even of factions within the established churches in Britain during the nineteenth century, as the world’s first urban, commercial, and industrial society was established and consolidated. This religious spontaneous order enabled Britain to shift from being a society of small, rural villages and towns based on local social controls to one of large, modern, urban conurbations while experiencing not crime and chaos but steadily declining rates of crime (Gattrell and Hadden 1980), illegitimacy (Hartley 1975), and drink and drug excesses (Wilson 1940). Britain was a more crime free and less deviant society in 1900 than it is today and than it had been 50 years before (Davies 1994).

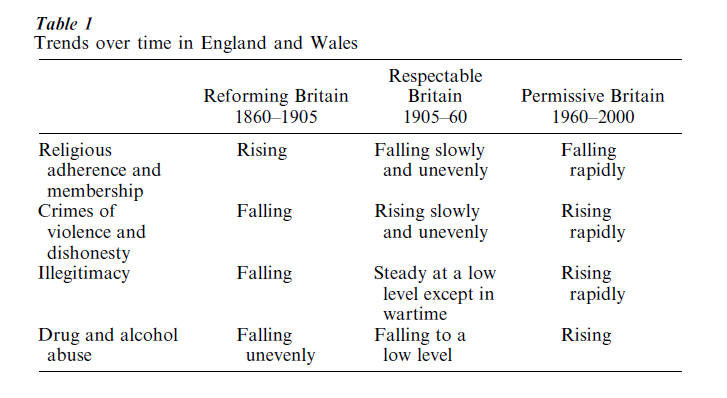

Over time the pattern of crime and deviance in Britain follows a -curve, falling markedly in the later half of the nineteenth century (Gattrell and Hadden 1980), reasonably stable in the first half of the twentieth, and rising very rapidly from the mid-1950s (Davies 1994). These changes are inversely shadowed by the growth and decline in church adherence in England and Wales, which grew rapidly in relation to population in the latter half of the nineteenth century and peaked in about 1904–5 (Brown 1992). There then followed an irregular decline with occasional periods of recovery until the late 1950s, after which there has been a steep and unreversed decline. There was a ∩ – curve in piety which was an exact inverse of the U – curve in crime and deviance. No other variable fits this pattern with any such degree of exactitude. It is very strong proof indeed of the effectiveness of spontaneous religious order as a means of social control. The relationship is summed up in Table 1 (Davies 1994, Hartley 1975, Lynn and Hampson 1977) showing the main trends between 1860 and 2000, trends that divide the period clearly into three phases ‘Reforming Britain,’ ‘Respectable Britain,’ and ‘Permissive Britain’ (Davies 1975).

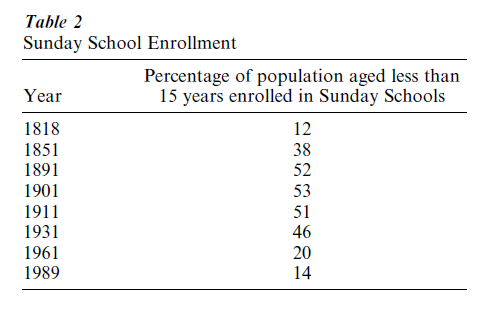

Religious adherence and membership, although at all times involving a minority of the adult population, were a good index of the strength of the values of respectability, and thus of spontaneous self-and social control in British society. The incidence of deviant behavior clearly fell and then rose in Britain as this form of social control rooted in religion first became stronger and then later went into decline. The churches and chapels were the crucial institution promoting respectability in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and membership and attendance were one way in which respectability could be acquired and proclaimed. Rising levels of membership and attendance gave those who were committed to their religion the confidence to promote and foster the virtues of self-control and respectability among the non-attending majority whose attachment to a church or denomination was at best nominal. To a substantial extent, though, they were receptive to the morality of respectability, and in particular they wanted it instilled in their children. The rise and the later fall of Sunday School enrollment and attendance shown in Table 2 (Gill 1992, Laqueur 1976, Martin 1967, Wilkinson 1978) is perhaps an even better measure of the changing importance over time of religion as a means of social control. It has been suggested reliably that between two-thirds and three-quarters of those enrolled were generally present in school on a Sunday (Gill 1992, p. 96).

The importance of popular Protestantism as a source of spontaneous social control and moral order in Britain during a time of massive internal migration to the new industrial and commercial towns and conurbations (Munson 1991) can be seen at work today in contemporary Latin America, a continent currently undergoing a similar transformation (Martin 1990). Migrants leaving small, agricultural communities to work in the industrial and services sectors in societies as diverse as Chile and Guatemala have, like their British predecessors, sought to create for them-selves through religion a spontaneous moral order, a social control based on respectability (Martin 1998, Martin 1990).

Protestantism has ‘once again created a critical mass of persons for whom self-discipline, a work ethic and the values of domestic rectitude have become second nature’ (Martin 1998, p. 28. See also Weber 1930). The truth has set them free from what otherwise would have been a morally degrading existence. Whether they will be able to sustain these virtues in the long run remains to be seen.

The importance of religion as an autonomous and potent means of social control has often been neglected by sociologists and political scientists, who are blinkered by their own obsession with economic and political power, and unable to appreciate the importance of religion. When they do turn their attention to religion as a means of social control, it is by choosing selectively examples such as the Inquisition, the Ayatollah Khomeini’s regime in Iran, or human sacrifice by the Aztecs, which enable them to caricature religion-based social control as backward, oppressive, and irrational. On the contrary, social control rooted in religion is as varied as any other form of social control, and the distinctive spontaneous forms of social control that religion has provided in some countries during the difficult transition from a traditional to an urban and industrial society have been remarkable for their peaceable nature and civilizing influence.

Bibliography:

- Brown C G 1992 A revisionist approach to religious change. In: Bruce S (ed.) Religion and Modernization. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 31–58

- Bruce S (ed.) 1992 Religion and Modernization. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Davies C 1975 Permissive Britain. Pitman, London

- Davies C 1994 Does religion prevent crime? Informationes Theologiae Europae, Internationales okumenisches Jahrbuch fur Theologie, Peter Lang, Cologne, Germany, pp. 76–93

- Davies C 1999 The fragmentation of the religious tradition of the creation, after-life and morality: Modernity not post-modernity. Journal of Contemporary Religion 14(3): 339–60

- Dumont L 1970 Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London

- Flew A G N 1987 The logic of mortality. In: Badham P, Badham L (eds.) Death and Mortality in the Religions of the World, Paragon House, New York, pp. 171–87

- Gattrell V A C, Hadden T B 1980 The decline of theft and violence in Victorian and Edwardian England. In: Gattrell V A C (ed.) Crime and the Law, The Social History of Crime in Western Europe since 1500, Europa, London

- Gill R 1992 Secularization and census data. In: Bruce S (ed.) Religion and Modernization. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 90–117

- Hartley S F 1975 Illegitimacy. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Inglis T 1998 Moral Monopoly, The Rise and Fall of the Catholic Church in Modern Ireland. University College Dublin Press, Dublin, Ireland

- Laqueur T W 1976 Religion and Respectability, Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Lynn R, Hampson S L 1977 Fluctuations in national levels of neuroticism and extroversion 1935–1970. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 16: 131–8

- Martin B 1998 From pre-modernity to post-modernity in Latin America: The case of Pentecostalism. In: Heelas P (ed.) Religion, Modernity and Post-modernity. Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp. 101–46

- Martin D 1967 A Sociology of English Religion. Heinemann, London

- Martin D 1978 A General Theory of Secularization. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Martin D 1990 Tongues of Fire, The Explosion of Protestantism in Latin America. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Munson J 1991 The Nonconformists, In Search of a Lost Culture. SPCK, London

- Polanyi M 1951 The Logic of Liberty. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

- Weber M 1930 The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Allen & Unwin, London

- Wilkinson A 1978 The Church of England and the First World War. SPCK, London

- Wilson G B 1940 Alcohol and the Nation. Nicholson and Watson, London