Sample Goddess Worship Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Goddess worship is integral to many religions, old and new. The ancient Mediterranean world contained abundant Goddess lore; today, Hinduism and Buddhism are richest in female divinities. Academic studies of these traditions trace their texts, histories, rituals, iconographies, theologies, intersections with economics and politics, and—most recently— implications for female status. This research paper builds upon such scholarship, but it aims to describe the contemporary phenomenon of Goddess worship as a choice by women and men who believe that worshipping

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

God in a female form will empower them spiritually, socially, or politically. Who is turning to Goddess worship, and why? What does this say about history, religion, and society? Are Goddesses ‘good’ for women? Although the material investigated here derives largely from Western contexts, one can detect the same recourse to Goddess figures by people in other cultures who seek transformation through potent symbols and personalities. But the ‘new’ Goddess worship of today, embracing and refashioning the Goddesses of ‘old,’ is not everywhere the same. A Wiccan member of The Fellowship of Isis may differ radically from an Indian author involved with the feminist press, Kali for Women. Thus to nuance the picture of this emerging phenomenon, non-Western experiences of contemporary Goddess appropriation—particularly Indian—are brought in as test cases for claims made about Goddess worship here in the West.

1. Seeking New Symbols

In Western countries, Goddess worship is typically viewed as a religious alternative for those disillusioned with the overwhelming maleness of Jewish and Christian religious imagery and social structure. Symbols of God as father, conqueror, judge, and lord are believed to enforce the patriarchal domination of women. Moreover, Western philosophical dualisms—soul body, sacred profane, transcendent immanent, rational emotional, and changeless changeable—justify the creation of hierarchy and demonize the lower halves, such that it becomes necessary to subdue sexuality, nature, emotion, and change. The new Goddess traditions also make historical charges—that Jews and Christians have wiped out indigenous Goddess-worshipping societies, Jews during the time of the prophets and Christians in the fourth to fifth centuries, when their emperors closed Goddess temples throughout the Roman empire. Indeed, as many critics claim, Jewish and Christian histories have systematically subordinated Goddesses and women, rather than according them equivalence in the theological and social spheres.

The most cogent justification for the need to reject the Judeo–Christian tradition for that of the Goddess draws upon theories about religious symbols. Following the work of Clifford Geertz, Carol Christ (1987, 1997) and other feminists have postulated that symbols have a direct relationship to sociocultural systems. Since symbols create powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations, shaping our understanding of the world and suggesting patterns of action, patriarchal symbols reinforce patriarchal social structures, which therefore appear uniquely realistic. Changes in the way women are perceived and treated can only come through the creation of new symbols, which empower women and undercut male dominance. As Birnbaum states, quoting Gloria Anzaldua, ‘nothing happens in the ‘‘real’’ world unless it first happens in the images of our heads’ (1993, p. 7).

2. Varieties Of Goddess Votaries

Western Goddess spirituality is heterogenous and flexible, and sits at the intersection of four large groups (Eller 1993, Puttick 1997). The first, known loosely as spiritual feminism or women’s spirituality, started in the early 1970s as a spontaneous grassroots movement. Cynthia Eller describes it as being founded on four premises: religion and ritual can be empowering for women; a healthy environment, peace, and community must be sought; Western history needs revising; and gender relations should be explored. Since many spiritual feminists stay within their birth traditions to work for justice and equality, not all women in this category worship Goddesses.

The second umbrella label is (neo-) paganism and Wicca, founded in the 1950s in Britain and based on the recovery of pre-Christian European religions such as Druidry and Odinism. In general, such groups believe in a dynamic balance between male and female; the centrality of fecundity; an immanent deity; care for the earth; the efficacy of ritual and magic; and the leadership of women. Goddesses are central to pagan religiosity, but not necessarily in isolation from male gods.

The concerns of spiritual feminists and Wiccans can be similar, as seen in the writings and practices of feminist witches Zsuzsanna Budapest and Starhawk. However, there are also frictions between the two groups. Since Wicca is not political, does not aim to strip away patriarchal domination, and advocates male female complementarity, some spiritual feminists view Wiccans as sexist. Wiccans return the compliment; for them, politics and feminism are irrelevant to spiritual growth.

A third set of related groups is referred to collectively as the New Age. Famous for their crystals, chakras, channeling, past-life regressions, astrology, and mind-over-matter affirmations, New Age individuals create a pastiche of religious self-help devices, many of which involve Goddess figures. Spiritual feminists and pagans often critique the New Age for its tendency to whitewash and sweeten Goddesses; for its racism, misogynism, lack of commitment to community struggle, and exploitation of cultures from which it borrows; and for its naive optimism, unhelpful in times of crisis (Christ 1997, Sjoo 1992).

The final group—new since the 1980s—of contemporary Western Goddess worshippers are the ecofeminists, eco-spiritualists, and Gaians (from Gaia, or Earth). Though not all of them gynemorphize the earth as a Goddess (there are Jewish, Christian, and Buddhist eco-feminists as well), most worship the earth as a mother Goddess and decry her desecration by modern industrial patriarchs. For Vandana Shiva, the Indian human rights activist, feminism is a form of ecology, and ecology is a revival of prakrti, the demonized but potent Hindu feminine principle of nature (1988, pp. 38–54).

3. Who Is She?

Like the variety of the Goddess movement, so also the Goddess herself. Her identity is multiple and fluid, changing depending upon the needs of her worshippers. Some women understand her as the affirmation of the female body, sexuality, and power, all of which have been downplayed in traditional Western religions. Although many feminists caution against too rigid a defense of female sexuality, as if biology were determinative of a women’s ‘essence’ (di Leonardo 1998, pp. 98–108, Gross 1998, pp. 159–70), others argue that creating a space for women to reclaim the positive aspects of their sexuality is so important that the project is worth the risks.

Another method of affirming female strength is through a Jungian perspective, where the Great Goddess is an archetype of the feminine, dark side of life. Following Robert Graves, Erich Neumann, and Joseph Campbell, modern Jungians claim not only to empower women and men through the recognition of the positive aspects of innate femaleness, but also to explain, through the theory of archetypes, why women who have never encountered Goddesses in real life can suddenly start creating and dreaming about them. Not all feminists and Goddess worshippers approve of the use of Jungian archetypes, however. Some protest that in revalorizing the feminine unconscious, the banished ‘other,’ one is creating a new version of the old male female dichotomy which subjugates women (Gross 1998, p. 190); others who worship a ‘real’ Goddess complain that Jungians relegate her to the ‘unreal’ realm of the mind (Christ 1998, pp. 86–8); and still others, drawing again upon Geertz’s work on symbols, prefer to create new ones rather than to adopt those postulated by a patriarchal psychological system.

The Goddess also has material manifestations. As indicated above, some women and men view her as the earth. Since we are all part of nature, we must celebrate, and not attempt to control, its cycles. ‘I feel deeply that the flight from finitude and death is at the root of the problems we face … Maybe something went wrong, massively wrong, when Platonism and Christianity became the dominant symbol systems of our culture. Maybe … the Goddess can help us…to love a life that ends in death’ (Christ 1987, p. 210). Often linked with this conception of divinity is the assertion that the Goddess is a relational symbol of embodied, immanent love.

Although many Western Goddess votaries might assent to the interpretations given above, the majority also worship the Goddess as a living presence. Some, choosing to stay within their Jewish and Christian contexts, derive inspiration from the feminine sides of God as revealed in the Bible or from their respective mystical traditions: Isaiah’s ‘womb language’; the emphasis on God’s wisdom; the Kabbalists’ Shekhinah, or presence of God; the Virgin Mary; feminine interpretations of the Holy Spirit; and Julian of Norwich’s Mother Jesus.

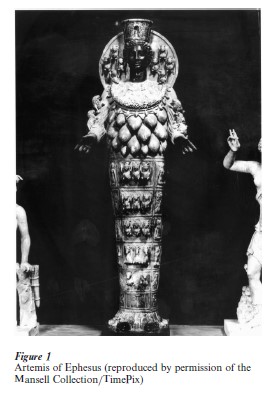

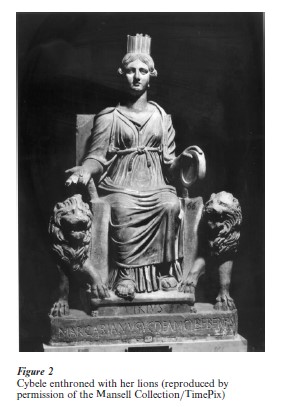

Others, finding the traditions of their birth irredeemably patriarchal, go outside in search of Goddess figures whom they can approach in prayer and ritual. The most frequent destinations for such seekers are Western, often European, traditions, where, even if the Goddesses are no longer the center of living cults, they are believed to be waiting, still puissant, able to heal. Examples include the Greek Demeter and Persephone, Aphrodite, Artemis (see Fig. 1), and Athena; the Egyptian Isis; the Sumerian Inanna; the Canaanite Astarte; and the Anatolian Cybele (see Fig. 2). Sometimes, though more gingerly, for fear of causing offense, Western Goddess worshippers also turn to figures from Native American tribes, such as Old Spider Woman, Corn Woman, and Serpent Woman, as well as to powerful ancestors and spirits from Africa.

Non-Western Goddesses also have devoted followings: the Japanese Amaterasu, the Hindu Durga and Kalı, the Tibetan Buddhist Goddesses Tara and Vajrayoginı; and the Chinese Buddhist Kuan-yin. Often these, and the Western deities mentioned above, are lumped together through superficial resemblances, archetypal links, and claims of historical connection, producing what Cynthia Eller calls the ‘grab-bag approach to feminist spirituality’ (1993, p. 75). Many criticize these dehistoricized approaches to Goddess worship as insulting, romantic, essentialist, and/orientalist. The fact that some modern Goddesses have been created afresh, according to elite needs—for example, Asphalta, the parking Goddess (Grey 1989)—does not assuage such fears. Nevertheless, most modern Goddess worshippers are sincere seekers, turning to female embodiments of the divine in a genuine search for new life.

Before concluding this introduction to the meanings of the Western Goddess, it is worthwhile noting that the reclamations under discussion appear not to be occurring among Muslims. There are three possible explanations: the minority status of Muslims in Western countries, which places them outside the liberal mainstream; the paucity of feminine images of the divine in the Qur’an; and the strict monotheism of Islam, which makes anathema the search for a Goddess figure.

4. How Old Is She?

One of the most controversial elements of the Goddess spirituality movement is a claim about origins, or the ‘Goddess Hypothesis.’ Currently championed by authors like Christ, Eisler, Gadon, Gimbutas, Spretnak, and Stone, but relying on the earlier works of Bachofen, Engels, Graves, and Neumann, this hypothesis rests on a belief that ‘there were past societies in Europe and the Near East, especially prior to the so-called invasions of the Indo-Europeans circa five thousand years ago, that were Goddess-worshipping, female-centered, in harmony with their environments, and more balanced in male-female relationships’ (Conkey and Tringham 1995, p. 206). Drawing upon archaeological excavations of female figurines (fertility ‘idols’ of ‘the Great Mother cult’), grave sites, and cave paintings, as well as anthropological research into modern-day ‘primitive’ societies who may be considered survivals from earlier eras, such authors see continuities from the time of the Upper Paleolithic period (32,000–10,000 BCE) and the Neolithic Revolution (9,000 BCE), down to the societies of Old Europe (6,500–3,500 BCE). What they have in common is a Great Mother cult and a social organization that is matrifocal (some claim matriarchal), earthbound, and peace loving. Present-day clues of this earlier time, when the ‘earth was believed to be the body of a woman and all creatures were equal’ (Birnbaum 1993, p. 3), can be seen in the black Madonnas of Europe and South America, as well as in tribes that revere women for their reproductive powers. All such societies ended abruptly with the arrival of the patriarchal, war-oriented IndoEuropeans in the middle of the fourth millennium BCE; they subjugated human women and tamed, desexualized, or slew their Goddesses.

Although some women and men find such a vision of the past to be liberating for the future, others find much to criticize (Conkey and Tringham 1995, Eller 2000, Motz 1997, Puttick 1997). How do we know what the female figurines represent without an adequate knowledge of the social systems that produced them? Is it possible that they had the same symbolic meaning over nearly 30,000 years? Is it not feminist essentialism to argue that all the figurines connote fertility, as if women have always been defined biologically? Most historical Goddesses, indeed, are not tied to fertility at all. And if it is allowable to read back to Old Europe by citing modern-day ‘survivals,’ what about contemporary groups in which there is matrilineality but male control, ritualized fertility but no Goddess worship, and Goddess veneration but little respect for women? The brunt of such criticisms is that the past is oppressive, not golden; it ill serves the women’s movement to idealize something unproven.

5. Is She ‘Good’ For Women?

Definitions of women and Goddesses that rely too much on biological determinism, Jungian archetypes, and the ‘Goddess Hypothesis’ are not the only contested issues in the Goddess movement. Another is the relationship between Goddess-worshipping societies and the status of their women. Do Goddesses serve patriarchal interests, or feminist ones? The evidence is mixed; although some Goddesses appear to serve their human devotees by undercutting patriarchal subordination, and although some women find strength in images of the divine feminine, other Goddesses reinforce their societies’ domination of women, such that feminists refuse to call upon them.

First, some positive correlations. Many modern Western women do indeed derive inspiration from their worship of Goddess figures: Luisah Teish, who looks to West African ancestor veneration; Charlene Spretnak, Christine Downing, and Carol Christ, who have found spiritual homes with the Goddesses of the Mediterranean; China Galland, whose life was changed by encountering Tara; and Rita Gross, who testifies about the inner transformation she experiences through the worship of Vajrayoginı. Very often, one woman’s metamorphosis leads to another’s, as occurs through the women’s pilgrimages to Crete led by Carol Christ.

It is not only Western women who are thus empowered. To take a few examples from South Asia, the audacity of the Goddess Radha vis-a-vis her lover Krsna provides Bengali women with models of assertiveness and resistance (Wulff 1997); forms of Durga empower Hindu devotees and holy women by their autonomy and puissance (Erndl 1997); women Tantrikas of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition find their spiritual aspirations mirrored in powerful images of the feminine divinity (Shaw 1994); and the activist Mother’s Front in Sri Lanka worships Kalı for fortitude in the midst of the civil war (de Alwis 1999). Sometimes the Goddess herself overturns patriarchal values; the South Indian Goddess Karumariamman allows menstruating women into her temple (Narayanan 1999, p. 69).

But there are also contrary indications. All 10 Goddesses whom David Kinsley (1989) describes in The Goddesses’ Mirror belong to societies in which men dominate women; the same is true for those catalogued by Motz (1997). Other scholars find similarly depressing inverse correlations between Goddess worship and freedom for women. Again, from South Asia: William Sax investigates the north Indian devotion to Nandadevı and finds that while the Goddess represents the trials of out-married daughters, her cult enables rather than undercuts their sorrows (1991); China Galland visits Bhaktapur, Nepal, and describes both her delight in the beauty of Durga worship and her horror at the thriving trade in child prostitution which exists alongside it (1998); and Lisa Hallstrom discovers that although devotees view the modern saint Anandamayı Ma as an incarnation of the Goddess, she is not considered a ‘woman,’ and feminist interpretations of her significance are discouraged (1999). The frustration of such a disjunction between expectations and reality is summed up by an eight-year-old girl in a story by Mrinal Pande: ‘when you people don’t love girls, why do pretend to worship them?’ (1990, p. 63).

Many women’s activists in countries such as India, therefore, eschew Goddesses as aids in their struggles. For Goddesses can validate a sexist model, as in the case of Sıta, the virtuous wife of Rama, or represent a romanticization of the past and a glorification of motherhood. Indian feminists, after initially turning to Kalı and Durga as symbols of empowerment, found them usurped by Hindu nationalists and deployed for divisive ends (Agnes 1995). One example is Durga Vahinı, or Durga’s Army, a Hindu nationalist women’s group. The Vahinı has revived female militancy—not in the service of women’s issues (caste, divorce, dowry, sati, or marital violence), which are not debated or fought for, but against Muslims (Pathak and Sengupta 1995). The eight-armed Durga gives women a new identity, but an identity that serves patriarchal values.

6. Trends, Evaluations

Goddess worship, wherever it is found, is diverse and controversial. Particularly since 1985 in the West, it is also a place where the popular and the scholarly meet and spar. Sometimes academic authors bemoan the theoretical backwardness that characterizes the public enthusiasm for Goddess spirituality and matriarchal histories, complaining that exhorting women to realize that ‘we’re all Goddesses within!’ vitiates the need for external change (di Leonardo 1998, pp. 104–7). But sometimes the meetings between popular and scholarly are not so antagonistic: Goddess-revering people of all stripes can and do join hands when it comes to issues of social justice and eco-spiritualism.

The revived Goddess spirituality of the West also provides opportunities for encounters of other types. The increasing ethnic mix of Western societies means that ‘new’ Goddess worshippers come into contact with those for whom Goddesses are a traditional part of their religious backgrounds. Sometimes Western votaries find this an inspiring, deepening encounter, and sometimes they do not. How, for instance, is one to incorporate the traditional practice of goat sacrifice into one’s Western worship of Kalı ? By the same token, many first-and second-generation immigrants find the appropriation of their Goddesses by mainly white Americans to be offensive. The Goddess movement is obviously a fertile field for intercultural exchange.

How then to evaluate this refashioning of ‘old’ Goddesses in the service of ‘new’ ideals and hopes? While from an academic perspective one might deplore the ‘Goddess Hypothesis,’ biological determinism, the perceived exploitation of ‘other people’s symbols,’ and a naive assumption that all women everywhere benefit from the Goddess, the debate, creativity, and diversity characteristic of ‘new’ Goddess worship in the West are evidence of laudable cultural vibrancy. Goddesses may not always, or even often, provide alternative models for women in today’s global societies. But as various studies have shown, in religious groups where women do have a leadership role, there is typically a feminine aspect to God (Sered 1994). Rita Gross makes the point differently when she asserts that even if Goddesses do not confer status or independence to women, they do contribute to psychological wellbeing. ‘Though the presence of goddesses does not guarantee equity for women, their absence almost certainly guarantees inequity for women’ (1998, p. 161). A final example from India: just because the slain Mrs. Gandhi was depicted in the press as a mother Goddess killed by her ungrateful Sikh children, who therefore deserved the violence unleashed upon them, there is no reason that Goddess symbolism, wrested from nationalist agendas and purposely reworked, could not be used for healing and hope. To echo Christ, echoing Geertz: people change as symbols change, and vice versa. That the denizens of the Goddess movement are trying to push this mutual process forward to their own ends is neither surprising nor unprecedented, though where the Goddesses ‘take hold’ and in what forms are matters for future interest.

Bibliography:

- Agnes F 1995 Redefining the agenda of the women’s movement within a secular framework. In: Sarkar T, Butalia U (eds.) Women and Right-Wing Movements: Indian Experiences. Zed Books, London

- Birnbaum L 1993 Black Madonnas: Feminism, Religion, and Politics in Italy. Northeastern University Press, Boston

- Christ C 1987 Laughter of Aphrodite: Reflections on a Journey to the Goddess. Harper & Row, San Francisco

- Christ C 1997 Rebirth of the Goddess: Finding Meaning in Feminist Spirituality. Routledge, New York

- Conkey M, Tringham R 1995 Archaeology and the Goddess: Exploring the contours of feminist archaeology. In: Stanton D, Stewart A (eds.) Feminisms in the Academy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- de Alwis M 1999 Motherhood as a space of protest: Women’s political participation in contemporary Sri Lanka. In: Jeffrey P, Basu A (eds.) Resisting the Sacred and the Secular: Women’s Activism and Politicized Religion in South Asia. Kali for Women, New Delhi, India

- di Leonardo M 1998 The Three Bears, The Great Goddess, and the American temperament: Anthropology without anthropologists. In: di Leonardo M (ed.) Exotics at Home: Anthropologies, Others, American Modernity. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 79–144

- Eller C 1993 Living in the Lap of the Goddess: The Feminist Spirituality Movement in America. Crossroad, New York

- Eller C 2000 The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won’t Give Women a Future. Beacon Press, Boston

- Erndl K 1997 The Goddess and women’s power: A Hindu case study. In: King K (ed.) Women and Goddess Traditions: In Antiquity and Today. Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN

- Galland C 1998 The Bond Between Women: A Journey to Fierce Compassion. Riverhead Books, New York

- Grey M 1988 Found Goddesses: Asphalta to Viscera. New Victoria Publishers, Norwich, VT

- Gross R 1998 Soaring and Settling: Buddhist Perspectives on Contemporary Social and Religious Issues. Continuum, New York

- Hallstrom L 1999 Mother of Bliss: Anandamayı Ma (1896– 1982). Oxford University Press, New York

- Kinsley D 1989 The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine Feminine from East and West. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

- Motz L 1997 The Faces of the Goddess. Oxford University Press, New York

- Narayanan V 1999 Brimming with Bhakti, embodiments of Shakti: Women of power in the Hindu tradition. In: Sharma A, Young K (eds.) Feminism and World Religions. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

- Pande M 1990 Girls. In: Holmstrom L (ed.) The Inner Courtyard: Stories by Indian women. Virago Press, London

- Pathak Z, Sengupta S 1995 Resisting women. In: Sarkar T, Butalia U (eds.) Women and Right-Wing Movements: Indian Experiences. Zed Books, London

- Puttick E 1997 Goddess spirituality: The feminist alternative? In: Puttick E Women in New Religions: In Search of Community, Sexuality, and Spiritual Power. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp. 196–231

- Sax W 1991 Mountain Goddess: Gender and Politics in a Himalayan Pilgrimage. Oxford University Press, New York

- Sered S 1994 Priestess, Mother, Sacred Sister: Religions Dominated by Women. Oxford University Press, New York

- Shaw M 1994 Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Shiva V 1988 Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Sur i al in India. Kali for Women, New Delhi, India

- Sjoo M 1992 New Age and Armageddon: The Goddess or the Gurus? Towards a Feminist Vision of the Future. The Women’s Press, London

- Wulff D 1997 Radha’s audacity in Kırtan performances and women’s status in Greater Bengal. In: King K (ed.) Women and Goddess Traditions: In Antiquity and Today. Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN