Sample Private Legal Systems Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Private legal systems are nonstate institutionalized means for obtaining compliance with the norms or rules of a social order. They comprise the numerous forms of social control that are part of group or organizational life, but that are not formally part of state law. They include, for example, the practices of disciplinary bodies, boards and councils of industrial organizations, the tribunals of professional or trade associations and labor unions, and the disciplinary committees of universities and colleges. They also include the peer sanctioning of relatively amorphous voluntary associations, such as self-help and mutual aid groups.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Mechanisms Of Control

Private legal systems bring about conformity to the normative expectations of their collective setting through one of three mechanisms for administering either positive or negative sanctions: (a) coercion, being the threat or use of negative sanctions that reduces a person’s social standing; (b) persuasion or ideological control that uses positive inducements to conformity; and (c) suggestion, that reminds people of their obligations, responsibilities and duties in relations with one another.

In some private forms, such as the disciplinary bodies of universities or professional associations, the administration of justice is elaborate, formalized and with considerable history and established precedent, and whose sanctions may involve fines, loss of privileges, or suspension of licensure. In other cases, such as the community or neighborhood association or the local meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous, the administration of justice may be minimal, implicit, or nonexistent, comprising simply of the exercise of sanctions such as ostracism, shaming, gossip, or ridicule. For discussion of related concepts readers should see African Legal Systems; Legal Pluralism; Folk Indigenous Customary Law; Conflict of Laws.

2. Significance

Nonstate private legal systems and their administration of justice are important because more people are directly governed by and controlled through them on a daily basis than they are by state law, which remains relatively distant from most people’s day-today life. However, while state law and its various agencies and operations are publicly accountable, private systems of justice often escape accountability. While numerous refinements and endless energy are invested in public systems of law to protect the individual’s right to due process, to guard against excessive or abusive use of state power, and to minimize arbitrary decisions, rarely are such limitations to potential abuse exercised on the day-to-day working of private legal systems and their forms of justice. Insofar as the ideal of reducing arbitrariness is the hallmark of legality, this is ‘a variable achievement’ (Selznick 1969).

3. Private Legal Systems As Types Of Law

Consistent with Weberian analysis, private legal systems are types of law insofar as they are guaranteed by the probability that physical or psychological coercion to bring about conformity to the order or avenge violation is applied by a staff of people holding themselves especially ready for that purpose. Yet, Selznick (1969) argued that if law is seen only in terms of coercive rules, its moral idealism, its progressive striving to reduce arbitrariness in the administration of justice, is overlooked. For Selznick (1969, p. 7) law is ‘generic’ in that it is ‘endemic in all institutions that rely for social control on formal authority and rule making.’ This means that the norm of legality is not confined to the state, but occurs in every group that develops rational rules to administer justice. However, while this approach accommodates the concept of private legal systems, it restricts legality to the formal rational, and discounts the informal, which in Weber’s terms may be both substantive and irrational, but nonetheless is a form of legal authority over those whom it exercises control.

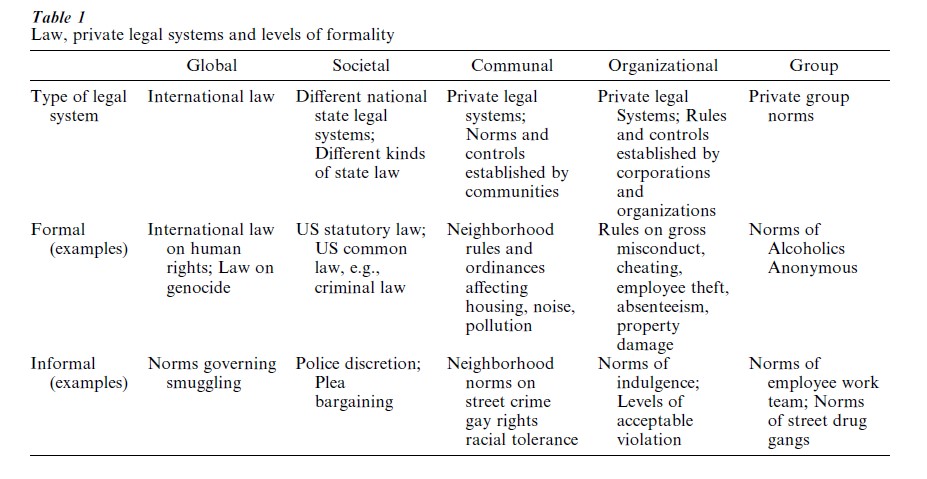

Building on Gurvitch’s (1947) more inclusive analysis, all legal systems, whether rational or irrational, can be considered as existing in two planes. On the horizontal plane is the range of legal systems differentiated by the scale of organizational complexity within which they are constituted and through which they primarily function. This horizontal continuum would range from the global to the group, with a variety of intermediate organizational fields including society, community, and organization. Within any organizational field there are many different types of organization and many types of groups. Moreover, each type of organization may exist in a wider context, but each also has a degree of separation from its encompassing social form, based on its own semiautonomous existence in relation to the whole, of which it is a part. Then, for analytical purposes, consider the degree of formality of the legal system in a vertical plane, as ranging from formal to informal. For Gurvitch, the formal is characterized by being organized, written, fixed, and planned in advance, whereas the informal is unorganized, flexible, spontaneous, and intuitive (see Table 1.) Clearly it is not necessary for informal systems of private law to be spontaneous, since they can be established over time and build up considerable institutionalized history as in the case of street gang initiation rituals.

This schema is helpful in that it shows us that informal social control is not the exclusive control mechanism of the group. While developed organizational forms, such as the state in capitalist industrial society, appear to be dominated by formal social control, such as criminal law, within law’s organization, and reflective of the groups that make it up, exist numerous levels of informal private justice working within, and often against the explicit principles of its wider system. Examples would include police discretion and plea-bargaining. Conversely, formal social control is not the exclusive mechanism of the state or formal organization. While levels of organizational development often preclude small groups from having highly formal private legal systems, they sometimes develop rudimentary formal controls (Henry 1983). Thus, each type of collectivity has depths of formal and informal operation. For example, an organization, such as a manufacturing company is governed by the regulations of formal state law, but also has its own non-state private legal system for administering internal discipline. Insofar as this relies on written formal rules, procedures, and penalties, it would be considered a type of formal private law. However, within the same company there may exist a range of groups of employees, of different professions, skills or trades, different unions, work teams and social cliques, etc. Each may exercise its own private collective control over its members. Arguably, the most effective system of control is that where the multiple kinds of social control, and each of their levels of operation from formal to informal, complement each other in bringing about conformity. Indeed, rather than using only one type of legal system, a collectivity typically uses a combination of types and of levels of legal system, simultaneously (Henry 1983).

4. The Interrelationship Between Private Legal Systems And State Law

Although private legal systems by definition, exist outside the state, they have a semi-autonomous relationship with state law (Moore 1978), being subject to its broad framework, yet within these constraints being free to create and enforce their own rules. That they exercise control consistent with the broad requirements of the state means that they can reaffirm state law, and so function as state surrogates. As such, private legal systems are a subset of the more generic notion of social control, which refers to broad societal, community, or organizational level processes such as socialization, education, social welfare, etc., that bring about conformity to societal social order. In this broader sense, private legal systems are a reaffirmation of the relations of order, part of the ongoing construction of a collectivity’s social reality. It is in this sense that private legal systems merge with ongoing daily interaction as an integral part of the constitution of group process to develop the appearance of stability, predictability, and order. This point is at the heart of Ehrlich’s (1913) observation that ‘living law’ is that which dominates life itself even though it has not been posited in legal propositions. Yet the semi-autonomy of private legal systems also allows for a contradictory and subversive role in relation to the state. This web of ‘legal pluralism’ (Pospisil 1971) may exist in harmony or conflict, reinforcing or undermining the social control of other private legal systems and even the formal law of the state, such that they may condone and even approve of behaviors that the overarching state system would condemn. For example, consider the toleration of some level of pilfering (theft) by employees in a food manufacturing company.

Clearly, any consideration of nonstate private legal systems, therefore, must also involve an examination of the theory of ‘legal pluralism’ and must address the varying interrelationships between the different types of social control and between their varying levels of formality. Further, insofar as private legal systems exist in an ambivalent relationship to state law, sometimes supporting it, at other times contradicting it, and even undermining it, consideration must also be given to how these forms relate to, and even constitute, the totality of control in a society.

4.1 The Limits Of Traditional Legal Pluralism

Recognition of the significance of nonstate forms of law has led sociolegal theorists to revise their thinking about the law and society relationship. The suggestion that state law and its institutions for administering justice are but one form of social control has been a core feature of legal pluralism from the foundations of theorizing about law. However, the legal pluralist tradition has focused on the character, source, and hierarchical place of nonstate normative orders in relation to state law. Until the mid-1970s, much of their argument explored the relationship between indigenous tribal custom and European colonial law (Pospisil 1971). This tradition saw indigenous orders as autonomous, independent, yet subordinate to colonial law. By the mid-1980s, the emphasis had shifted to non-colonial societies but retained its concern with the hierarchical power relations between dominant and subordinate law forms. Thus, many critical theorists take ‘informal justice institutions’ as the subordinate normative order and examine how they serve the ideological function of blurring the power of the state so that it appears to be a benign part of the social fabric. They have shown that this ideological subordination is accomplished by the co-optation and exploitation of a human desire for informal, localized, community justice, and that the episodic tendency toward an ‘informal,’ decentralized state control serves a dual legitimating and net-widening control function for the state (Cohen 1985). However, these criticisms seem more applicable to the growth of state sponsored dispute settlement institutions, community policing, and restorative justice, than to explaining the state’s interrelationship with other, established, private legal systems, which have largely been ignored. During the late-1980s, attention turned to the contribution that the social relations of these nonstate systems of law make in constituting state law.

4.2 Private Legal Systems And Constitutive Legal Theory

Critical contributions to the legal pluralist debate argued that recognition of the interpenetrating role of non-state normative orders requires a new conception of law in society. This has been variously referred to as the ‘relational theory of law,’ ‘constitutive theory,’ and ‘postmodernist’ or ‘deconstructionist’ theory. Constitutive theory is based on the idea that law is, in part, social relations and social relations are, in part, law (Moore 1978, Fitzpatrick 1984, Henry and Milovanovic 1996). It is the movement and tension whereby these are socially constituted, ‘the way ‘‘society’’ is produced within ‘‘law’’’ as David Nelken has described it and how law is produced within society, rather than how they interact, that is crucial to understanding the law–society interface. Thus, instead of assuming that state law is the hub of social control whose spokes radiate as unidirectional pathways of influence to other social and normative orders, constitutive theory also directs our attention to the reverse process: forms and mechanisms whereby legal relations are penetrated by extra-legal social relations, often constituted as non-state private legal systems. A constitutive approach examines both the presence and the source of other social forms, which as Alan Hunt says, ‘are not simply variant forms of legal reasoning but derive their significance and their legitimating capacity from the forms of social relations from which they originate’ (see Hunt 1993).

It is not, then, just that law is created by classes or interest groups, whether instrumentally or symbolically, to maintain or increase their power. Rather, some of the relations of these groups, particularly their rules and procedures are, and indeed become, the relations of law, as relations of law similarly become social relations. This dialectical analysis suggests that ‘any site of social relations is likely to be traversed by a variety of state and non-state legal networks’ and that ‘what constitutes ‘‘the law’’ in any specific context will depend upon which legal networks (or more precisely which parts of which networks) intersect in that context, how these orders are mobilized, and how they interact’ (O’Malley 1991, p. 172).

Thus, instead of treating law as an autonomous field of inquiry linked only by external relations to the rest of society, or investigating the way ‘law’ and ‘society’ as concrete entities ‘influence’ or ‘affect’ each other, constitutive legal theory takes law as its subject of inquiry, but pursues it by exploring the interrelations between legal relations and other social forms. As Hunt has observed, constitutive theory explores how law or legal relations are generated within non-legal social relations and how legal relations and social relations interpenetrate (Hunt 1993).

Peter Fitzpatrick (1984, 1992) incorporated several contributions (Foucault 1977, Moore 1978, Macaulay 1963) about the notion of interrelationships between law and the larger social matrix within which it is set, into the concept of ‘integral plurality.’ He says that the reason state law is, in part, shaped by the plurality of other social forms, while these forms are simultaneously being shaped by it, is because ‘elements of law are elements of other forms and vice versa.’ While law incorporates other forms, transforming them into its own image and likeness, the process is not unilateral but mutual, such that ‘law in turn supports the other forms but becomes in the process, part of the other forms.’ As such, ‘state law is integrally constituted in relation to a plurality of other social forms’ and ‘depends on social forms that tend to undermine it’ (Fitzpatrick 1984).

Fitzpatrick’s theory of integral plurality is a considerable advance, both over earlier legal pluralism, and over critical legal theory, for it demonstrates that there is not so much a unilinear relationship with other social forms but rather that ‘law is the unsettled product of relations with a plurality of other social forms. As such, law’s identity is constantly and inherently subject to challenge and change.’ Fitzpatrick’s fundamental insight was to recognize that state law obtains some of its identity from its interrelationship with non-state forms and vice versa; that without this connection each would be constitutively different.

Fitzpatrick (1988, 1992) argues that the interrelations between state law and nonstate normative orders forms new entities, as a common discourse and set of practices is worked out between participating arenas of power. This is particularly evident in the context where law is being synthesized from other existing sets of rules and norms. He says that in the process of synopsis of existing rules and practices, the participating networks retain their own relative autonomy, but corresponding structures are formed which merge selected elements of the component networks into an emergent whole that becomes the new law. Pat O’Malley, developing this idea further, describes these attempts at legal synthesis as ‘synoptic projects’ which, are characterized by the emergence of a common and integrating discourse and set of practices worked out between interacting agencies. Such negotiation involves suppression of incompatible elements of the different participating agencies, knowledges and practices, translation of other elements into more compatible forms, and the integration of all into a workable whole, albeit often inconsistent, labile, and conflicting. In this process emergent, synthetic, or synoptic social practices and knowledges may appear (O’Malley 1991, pp. 172–3)

O’Malley claims that such ‘synoptic projects’ are most likely to occur where changing conditions, such as the emergence of obstacles to the continued effectiveness of existing arrangements, make their continued operation problematic. For others, such as Santos (1987) and Teubner (1992, pp. 1453–4), the process is one of ‘interdiscursivity’ where intraorganizational legal discourse ‘productively misunderstands,’ and misread (through their rereading, reinterpreting, reconstructing, and reobservation) ‘organizational self-production as norm production and thus invents a new and rich ‘‘source’’ of law.’ A similar misreading occurs, says Teubner, when the organization reincorporates legal rules developed and refined in disciplinary proceedings and makes use of them to restructure its organizational decision making.

In summary, developments during the 1990s in constitutive legal theory have taken a postmodernist stance arguing that law is mutually constituted through social relations and discursive misreading. The discursive processes of nonstate private legal systems with which state law is interrelated and interwoven provides a significant context of synoptic projects wherein old power is molded into new forms. Although critical of this new legal pluralism from the perspective of legal autopoiesis, Teubner (1992, p. 1443) accurately observes, that the relations between the legal and the social are characterized by ‘discursive interwovenness,’ ‘are highly ambiguous, almost paradoxical: separate but intertwined, closed but open.’ He argues that this new legal pluralism is ‘no longer defined as a set of conflicting social norms in a given social field but as a multiplicity of diverse communicative processes that observe social action under the binary code of legal illegal’ (Teubner 1992, p. 1451). It follows, as O’Malley (1991), Hunt (1993), and Santos (1987) have argued, that to understand the form and process of state law, it is crucial to establish the social sources of the nonstate forms and private legal systems with which it is interrelated and thereby partially constituted.

Although much has been said about how law shapes social forms, and about how interests shape law, until mid-1980s, little research had been done on the way that semi-autonomous non-state private legal systems interrelate with and constitute state law while also being constituted by it. However, as Sally Merry has observed, the study of the way nonstate normative orders constitute state law is in its infancy. Importantly, the few studies exploring this interrelationship tend to show how the human agents who penetrate state law through introducing normative content from private non-state arenas, are drawn to reproduce state law more than they are to transform it. Neglected is the extent to which their agency contributions, as carriers for the private normative systems, transform that law in the process of constituting it. A critical research question becomes how private legal systems, such as professional self-regulatory bodies, industrial discipline and dismissals rules and procedures, and the variety of other nonstate forms of social control are constitutive of state law.

In considering the theoretical significance of constitutive legal theory to understanding the relationship between law and private legal systems it is worth stating the obvious. Law and particularly statutory law creation, is often a deliberate effort to incorporate and synthesize custom and practice, norms and rules prevailing in other settings into a general legal framework. The point, however, is that by recognizing the relative autonomy of these nonstate systems of private law, and simultaneously recognizing their ability to interrelate with state law, constitutive theory allows for the possibility that law creation will have an unpredictable outcome. In this process the eventual product is always unintentionally different from what its drafters will have intended. This is so, precisely because of the relative autonomy of the relations of non-state private legal systems.

Bibliography:

- Cohen S 1985 Visions of Social Control. Polity Press, Oxford, UK

- Ehrlich E 1913 Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Fitzpatrick P 1984 Law and societies. Osgoode Hall Law Journal 22: 115–38

- Fitzpatrick P 1988 The rise and rise of informalism. In: Matthews R (ed.) Informal Justice? Sage, London

- Fitzpatrick P 1992 The Mythology of Modern Law. Routledge, London

- Foucault M 1977 Discipline and Punish. Allen Lane, London

- Gurvitch G 1947 The Sociology of Law. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Henry S 1983 Private Justice: Toward and Integrated Sociology of Law. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Henry S, Milovanovic D 1996 Constitutive Criminology: Beyond Postmodernism. Sage, London

- Hunt A 1993 Explorations in Law and Society: Toward a Constitutive Theory of Law. Routledge, London

- Macaulay S 1963 Non-contractual relations in business: A preliminary study. American Sociological Review 28: 55–66

- Moore S F 1978 Law as Process. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- O’Malley P 1991 Legal networks and domestic security. Law, Politics and Society 111: 170–90

- Pospisil L 1971 Anthropology of Law. Harper and Row, New York

- Santos B S 1987 Law: A map of misreading. Toward a postmodern conception of law. Journal of Law and Society 14: 279–302

- Selznick P 1969 Law, Society and Industrial Justice. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

- Teubner G 1992 The two faces of Janus: Rethinking legal pluralism. Cardozo Law Review 13: 1443–62