Sample Judges Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

A judge is a public officer appointed to administer the law in a Court of Justice impartially and independently. Judicial independence is instrumental to judicial impartiality, since only an independent judge can be expected to be fully impartial: hence ‘his and it usually is his’ configuration as an officer within some governmental structure, a measure originally meant to protect him against pressures from the confronting parties (Shapiro 1981). However, while this official status of the judge may provide protection against the parties it may also facilitate pressures and influences from those to whom he owes his office. In some highly infrequent cases (such as early Roman Law) the judge is freely elected by the parties who commit themselves to abide by his decisions. However in most historical instances the judge’s authority and binding capacity is independent from the will of the involved parties and derives from the backing granted to his actions by the political system. This creates a direct link between the legitimacy of judicial institutions and the type of legitimacy of the prevailing form of political government. Judicial impartiality can thus be expected to be reasonably guaranteed only under strict democratic rule, one of the basic requisites of a democratic polity being the existence of an effectively independent judiciary.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Officially empowered to determine in a binding way with which of the contending parties lies the legal right, the judge constitutes a key, central figure in all legal systems, past or present. However, the judge is but one among other possible conflict-solving institutions. Rather than as a discrete, fully differentiated category, he can be better understood as one of the extremes of a continuum that would run: go-between, mediator, arbitrator, judge (Shapiro 1981, p. 3). All these roles require an impartial implementation but differ in the degree of formalization and depersonalization presiding the relation with the contending parties. The go-between, who operates on a pure consent basis, represents the more informal, face-to-face, and equity-oriented end of the continuum; the judge, professionally, trained, vested with official authority and required to lack all personal acquaintance with the parties, occupies the opposite end.

As societies become more complex and differentiated, and as the state-controlled legal system increases its centrality in social life, the role of the judge gains predominance. However, the other conflict-solving roles do not disappear; instead, they subsist as alternative—and usually very active—instances. The continuum can be thus perceived as a cumulative process, allowing for the emergence of progressively more complex and formalized agencies of conflict resolution that co-exist with the preceding ones.

1. Types Of Judges

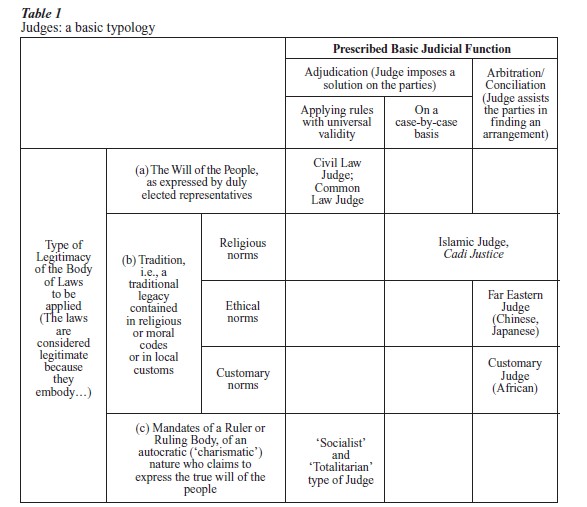

A basic typology of judges can be attempted from the combination of three factors intervening decisively in the shaping of judicial roles. In the first place, the type of legal system within which the judge operates: a basic distinction can be made between Western legal systems (comprising both Common Law and Civil Law systems), and all other types of systems, such as Far Eastern (Chinese and Japanese), Religious (Islamic or Hindu), or Socialist (see Zweigert and Kotz 1998). In the second place, the type of political legitimacy behind the body of laws to be applied, and consequently behind the political system which upholds those laws (Weber 1947). Third, the basic function that is attributed to the judge: a basic distinction can be made between authoritative adjudication and mediating arbitration. The following classificatory grid (Table 1) results:

Three basic configurations of the judicial role can thus be established:

(a) Democratic judge. A type of judge who adjudicates cases applying rules of general validity, enacted by duly elected representatives of the citizenry. This type of judicial system corresponds to representative democracies (legal-rational type of domination in Weberian terms). There are two possible formats for the democratic type of judge: Common or Civil Law.

(b) Traditional or predemocratic judge. A predominantly arbitrating, conciliatory type of Judge who applies norms embodying a traditional legacy, contained in religious, moral, or ethical codes, or in local customs, mores, or folkways. This type of judge would correspond to the Weberian category of ‘traditional’ political domination. Several classical types of judicial roles could be included within this category: the Islamic type of judge (who attempts conciliation—if and when the compromise does not permit what is forbidden or does not forbid what is permitted by the religious law—or who adjudicates on a case-by-case basis according to equity); the traditional Far Eastern Judge (Chinese or Japanese), more concerned with mending and preserving social harmony and equilibrium than with legal arguments or questions of individual rights; and the African or Native-American type of customary judge.

(c) Nondemocratic judge. A type of judge corresponding to autocratic political situations where the norms to be applied may be claimed to express the will of the people, but as interpreted and elaborated by an autocratic ruler (or ruling body), self-appointed as exclusive, natural spokesman for the collective will, and as such above any need for elective confirmation. This third situation would be the equivalent to Weber’s concept of charismatic rule.

2. Increasing Convergence

This threefold typology provides basic global models or ideal-types but is not meant as a description of real contemporary judicial systems. The judicial systems of the more economically developed and more democratically stable countries would generally fit well into the first (‘democratic judge’) category. Most other countries, striving in many cases to consolidate modernized and democratic polities, and as such immersed in transitional situations, represent mixed, intermediate stages. However, the generalization can be made that as processes of economic, social, and cultural globalization take place at a world scale, and as political democratization and the rule of law tend to become increasingly undisputed, universal goals, the tendency can be detected in most developing countries towards the adoption of judicial systems parallel to the two models of Justice prevailing in stable democracies (predominantly, the Civil Law type of judicial system). In quite a few cases this has implied some degree of denaturalization of the imported model, since the modern Civil Law (as well as the Common Law) type of Judge is designed to function under democratic conditions. Certainly this was not always the case: both systems (Civil and Common law) had emerged and consolidated well before the modern idea of the rule of law had even begun to develop. But their current configuration results from the substantial redefinitions they both experienced in the wake of the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century.

3. Judicial Systems In Developing Countries

Purely customary judicial systems can be now said to have become a rarity of merely anthropological or historical interest. By 1990, all Francophone African countries, with the only exception of Cameroon, had suppressed all types of customary courts, establishing a State system of Courts of the Civil Law type (Mangin 1990). In Anglophone Africa, customary courts are still allowed to exist in most countries, but as marginal institutions, their decisions being in any case appealable to State Courts, in most cases modeled along Common Law lines (Coldham 1990). One of the most conspicuous instances of Far Eastern traditional type of Judge, the Japanese, is now extinct and has given way to a Civil Law type system of Justice, with some elements of Common Law (Oda 1992, quoted in Zweigert and Kotz 1998).

Apart from China, one of the few remnants of the ‘socialist’ category of judicial system, most traditional systems are experiencing assimilation to the Western models. In India, where a process of hybridization gave birth to ‘Anglo-Muhammadan’ and ‘Anglo-Hindu’ law (Zweigert and Kotz 1998, pp. 310, 318), these bodies of law are administered by State judges in Common Law style.

In the case of the Islamic world a distinction has to be made between: (a) countries (such as Iran or Afghanistan) which in the wake of Islamic fundamentalist revolutions reorganized as Islamic Republics and which would still fit into the traditional religious category of judicial systems; and (b) countries (such as Egypt, Tunisia, or Jordan) which though experiencing in different degrees a trend towards the re-Islamization of social, legal, and political institutions still maintain a secular State-courts system created in most cases in the 1950s and 1960s, along the Civil Law model (Botiveau 1994).

4. Civil And Common Law Judges

The two types of judicial systems increasingly predominant in the contemporary world (Civil and Common Law) share a basic common, though distant, root: Roman Law, Justinianean and Classic, respectively (van Caenegem 1988). Their historical development led to differing legal and judicial traditions: Common Law is ‘judge-made law, that is to say (consisting of ) rules to be collected from the judgments of the Courts’ (Dicey 1905 1963), whereas codification stands out as the basic identifying feature of Civil Law (Merryman 1969). But they both embody what seems to be the final stage of the centuries-long process of evolution of the Western legal tradition. As pointed by Berman (1983) the emergence of Canon Law (which gave rise to the first full legal system), the Protestant Revolution (which secularized the legal world) and the English Revolution (which established the supremacy of Parliament) paved the way for the two versions of democratic judicial systems predominant today and brought about by the American (1776) and French (1789) Revolutions. As democratically reborn judicial systems, both the Civil Law (as reshaped by the French Revolution) and Common Law (as amended in American soil) share a similar contextual prerequisite for their adequate operation: the existence of the rule of law within a pluralistic, representative democracy.

However, both systems diverge in the way in which they attempt to keep the organization of Justice in line with the commonly shared dogma of popular sovereignty. The variant of the Civil Law originated in the French Revolution was basically intended to prevent judges from interfering with the popular will as expressed in the statutes enacted by duly elected representative bodies—a reaction against the preeminence of Parlements under the Ancien Regime. In the new, democratic situation the judge had to be in Montesquieu’s words just ‘the mouth of the law.’ Only from an unswerving application of democratic laws would the judge acquire a democratic character. In contrast, the main purpose of the judicial system established by the 1787 American Constitution was to make of the judge an essential element of the system of checks and balances that the new democratic polity was intended to be. To this effect, the judge had to apply the new statute law which had been democratically enacted (and which should be given priority in cases of collision with judge-made law); at the same time he was empowered to insure that statutes passed by ephemeral, temporary majorities would not go against the basic covenant contained in the ‘supreme law of the land’ (i.e., the Constitution).

As a consequence, two clearly differentiated models of ‘democratic Justice’ crystallized. On the one hand, the Common Law judge, as watchman of the Law, that is, of the ‘patchwork quilt of legislative provisions held together by thread woven out of general principles and sewn by the judges’ (Bell et al. 1998, p. 5), performs his functions with a basic policy-implementing orientation (Damaska 1986) predominantly within an adversarial system. On the other hand, the Civil Law judge, as a specialized anonymous civil servant decides the cases brought to him by applying a body of written legal norms, which is assumed to provide a complete and coherent repertoire of solutions; his functional orientation is inquisitorial and conflict solving. Intended to be a system of Justice rigidly respectful with the popular will, the Civil Law system turned out in practice to be a machinery of Justice Administration insulated from politics. Although this sounds favorable, what it means is that the Civil law model of Justice, devised for a democratic setting, proved equally functional when the overall political system ceased to be democratic. The system had been designed to provide a dutiful application of the laws in force, whatever their nature, not to scrutinize their legitimacy or interpret their contents. A change from democracy to autocracy meant no difference for the internal logic of the system, which could continue operating practically unchanged. The cases of Italy, Germany, and Spain in the twentieth century, to quote but some particularly conspicuous cases where breakdown of democracy, autocratic rule, and return to democracy did not entail any proportionally correlative reorganization of the judicial system (and even just marginal changes in the composition of the judiciary) provide a telling example (Toharia 1975). This unintended political floating ability and adaptability of the Civil Law model explains the successive attempts to amend its original late-eighteenth-century design in order to reinforce its original democratic structure. The increasing importance given to jurisprudence (or binding judicial interpretation of norms), a word which Robespierre wanted to see removed from the French vocabulary; the gradual introduction of varying forms of judicial review (in most cases in the form of Constitutional Courts) largely under Hans Kelsen’s influence in the 1920s and 1930s; the increasing questioning of the inquisitorial principle (which in the early twenty-first century is still in force, even though it is likely to disappear soon in three European Civil Law systems—France, Spain, and Portugal); and new forms of judicial activism (Guarnieri and Pederzoli 1996) are clear examples of the reorganization that the original structure has been experiencing. In a sense, these changes reflect an increasing pattern of convergence between Civil and Common Law models (Cappelletti 1989), a convergence which goes both ways: the impact that the legal system of the European Union is having on the legal and judicial practices of the United Kingdom has also meant substantial and gradual redefinitions of some basic Common Law features (White 1999).

5. The Selection Of Judges

A key element in the configuration of any judicial system is the way in which judges are selected. An ideal system of judicial recruitment should allow for: (a) the selection of competent and qualified persons; (b) thorough mechanisms unlikely to impair their impartiality and independence while in office; (c) making room for mechanisms of discipline, evaluation, and accountability of the judicial personnel; and (d) aiming to create a judiciary as representative as possible of the social body (in terms of ideology, social class, gender, race, religion, or other relevant social attributes). These four requirements are obviously difficult to meet and most existing systems of judicial recruitment attempt to achieve them through a wide variety of arrangements, which probably explains why ‘no other governmental official is selected by so many different methods’ as the judge (Stumpf 1998, p. 135).

A basic, preliminary distinction can be made between professional and bureaucratic systems of selection (Guarnieri and Pederzoli 1996), corresponding respectively to Common Law and Civil Law judicial systems. The professionalized selection looks for judges among already experienced, practicing lawyers which produces an older body of judges who have relatively short tenure as judges. (On mechanisms of selection see Judicial Selection.) By contrast, the bureaucratic system of selection prevailing in Civil Law systems allow for much longer judicial careers: from an average entrance age barely around or well below 30, to compulsory retirement around age 70 or even 75. The system is not meant to select mature, experienced lawyers and make them judges but rather to select young law graduates, without any previous legal practice, and prepare them for a lifelong career in the judiciary. The sense of achievement within the legal profession and the social aura and moral auctoritas that characteristically go with the image of the Common Law judge, is lacking in his Civil Law counterpart.

6. Judges’ Social Representativeness

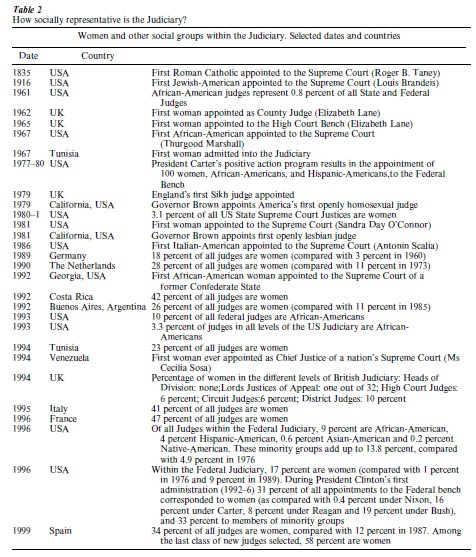

As professionals called to perform a highly specialized task implying extensive legal training, judges have tended historically to be recruited among members of educated, well-to-do sectors of society. This has originated an almost universal double structural bias within all judiciaries: a class bias (middle-to lower-class people, as well as people from minority groups, were likely to be strongly under-represented) and a gender bias (women were particularly likely to be strongly under-represented, as a result of the late recognition of their rights to equal education and equal access to professional life). A third, additional bias might even be said to have traditionally characterized the Judiciary: a conservative bias (as suggested originally by Max Weber, who pointed to the inherent conservative implications of legal reasoning and thence its more likely appeal for conservative-minded persons). As a result women, members of minorities, persons of lower-middle-or lower-class origin and people with ideologically progressive orientations were only rarely found within judiciaries.

To a large extent, all these biases seem to be gradually fading, as educational systems have become more inclusive and affirmative action programs have promoted higher levels of social equality. As for the social origin of their members, Civil Law judiciaries have been traditionally less elitist than their Common Law counterparts: in countries such as France, Italy, or Spain most judges tended to come from rural and middle-to low-middle-class families whereas in the US or in the United Kingdom urban upper or upper-middle-class origin usually prevailed. But in both cases the presence of judges with lower-or working-class origin was practically nil. This situation is changing substantially in both systems as judiciaries gradually become more representative of the prevailing social structure (Toharia 1987). The data in Table 2 reflect the gradual increase of social pluralism within most judiciaries since the 1970s. The change is particularly perceptible with respect to the increased presence of women, especially in civil law systems. The universalistic, competitive nature of the bureaucratic process of selection (generally based purely on personal performance in public entrance examinations, which leaves less room for blatant discrimination), and the fact that it takes place at a much earlier point in life seem to account for this seemingly more advanced degree of feminization of most Civil Law judiciaries. The presence of women within the judiciary may be said in any case to have passed well beyond the ‘tokenization’ phase, and to be becoming a fully institutionalized pattern. Even in Arab countries such as Tunisia, in spite of the controversy reopened by the religious fundamentalists’ questioning of the eligibility of women for judicial office, in 1994 one out of every four judges was a woman (Botiveau 1994). Racial and religious minority groups appear to have also increased their presence within the judiciary, though to a somewhat lower degree. As for the ideological bias the issue seems to have lost much of its former intensity. In Common Law countries, appointment or direct election of judges on the basis of their ideological orientation is perceived as a legitimate way of creating a bench that ‘looks like the country.’ In Civil Law countries, where judicial systems are supposed to be person proof, the scant data available indicate nonetheless that the ideological composition of the judiciary tends to reflect quite closely the ideological pluralism prevailing in the global society (Toharia 1987). The pattern of affiliation to the ideologically oriented unions of judges existing in countries such as Italy, France, or Spain provides an additional evidence of such pluralism.

Bibliography:

- Bell J, Boyron S, Whittaker S 1998 Principles of French Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Berman H J 1983 Law and Revolution. The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Botiveau B 1994 La loi islamique et jugement moderne. Droit et Cultures 28: 25–45

- van Caenegem R C 1988 The Birth of the English Common Law, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Cappelletti M 1989 The Judicial Process in Comparative Perspective. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Coldham S 1990 Les systemes judiciaires en Afrique anglophone. Afrique Contemporaine 156: 27–37

- Damaska M R 1986 The Faces of Justice and State Authority. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Dicey A V 1905/1963 Law and Public Opinion in England. Macmillan, London

- Guarnieri C, Pederzoli P 1996 La Puissance de Juger. Editions Michalon, Paris

- Mangin G 1990 Quelques points de repere dans l’histoire de la Justice en Afrique francophone. Afrique Contemporaine 156: 21–6

- Merryman J H 1969 The Civil Law Tradition. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

- Pannick D 1987 Judges. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Shapiro M 1981 Courts. A Comparative and Political Analysis. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Stumpf H P 1998 American Judicial Politics, 2nd edn. PrenticeHall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

- Toharia J J 1975 El Juez Espanol. Un Analisis Sociologico. Tecnos, Madrid, Spain

- Toharia J J 1987 Pleitos Tengas. Introduccion a la Cultura Legal Espanola, 1st edn. CIS Siglo Veintiuno de Espana Editores, Madrid, Spain

- Weber M 1947(1925) The Theory of Social and Economic Organizations. Oxford University Press, New York

- White R C A 1999 The English Legal System in Action. The Administration of Justice. Oxford University Press

- Zweigert K, Kotz H 1998 An Introduction to Comparative Law. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK