Sample Legal Aspects of Property Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Property encompasses the governance of resources— real property (land), natural resources, and personal property (chattels and intangibles, including copyrights, patents, stocks, claims of right). Natural law theory, beginning with Aristotle and perhaps best articulated in the writings of John Locke (1698), posits that ‘life, liberty, and property’ exist naturally as a matter of fundamental principles of justice, irrespective of the state. Echoing Locke’s formulation, the United States Constitution provides that a person may not ‘be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.’ By contrast, legal positivists, such as Jeremy Bentham (1789), assert that property rights arise only to the extent that they are formally recognized by the state: ‘Property and law are born together, and die together. Before laws were made there was no property; take away laws, and property ceases.’ Both views give content to what we understand as property. Legal positivism captures the practical reality that legislatures and courts define property rights in most societies, and that property rights have practical meaning only to the extent that they are enforceable. Nonetheless, natural law (and other philosophical frameworks) inform the content of property rules by providing the justification for state-created rights.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Philosophical Justifications For And Critiques Of Private Property Rights

Waldron (1988) suggests that property is best viewed as a ‘system of rules governing access to and control of material resources.’ These rules are often characterized as a bundle of rights—in the case of land, the rights to possess (or occupy), to exclude, to use, to transfer, to enjoy fruits, and to alter or destroy—which can be allocated in different ways. Particular bundles represent different conceptions of property, which derive from one or more philosophical justification.

1.1 Labor Theory

John Locke (1698) offered a strong natural rights justification for private property, which remains a central pillar of property theory today. Beginning with the proposition that all humans possess property in their own ‘person,’ Locke argued that

[t]he ‘labour’ of his body and the ‘work’ of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the stat[e] that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labor with it and joined to it something th[a]t is hi[s] own and thereby makes it his property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it that excludes the common right of other men. For this ‘labour’ being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to, at least where there is enough and as good left in common for others.

Locke’s theory is widely viewed as justifying first possession as a basis for acquiring property rights (Rose 1985, Epstein 1979). While useful as a basis for establishing rights in land and raw materials in a world of abundant unclaimed resources, Locke’s theory significantly qualifies the laborer’s claim in a world of scarcity—requiring ‘enough and as good left in common for others.’ Waldron (1988), Rose (1987), Ryan (1984), Becket (1977), and Schlatter (1951) elaborate and critique Locke’s justification for private property rights.

1.2 Libertarianism

Drawing upon Lockean principles, libertarians emphasize individual freedom to control and alienate their private property. Nozick (1974) asserts that the state should play no role in distributing or redistributing property acquired properly, apart from respecting the voluntary transfers of property owners. Epstein (1985) argues for a broad interpretation of the government’s obligation to compensate owners of private property for regulation and other governmental decisions interfering with private property rights.

1.3 Utilitarianism

First articulated by Jeremy Bentham (1789), utilitarianism judges the allocation of resources and the design of governance institutions on the basis of the utility or individual satisfaction that they produce. In applying this theory to property rights, utilitarian scholars have focused principally upon the inefficiency that can result from incomplete or shared resource ownership. In a now classic work, Hardin (1968) describes the ‘tragedy of the commons,’ whereby regulated access to a common pasture (or any other common resource such as air, water, or roads) results in overuse. Hardin suggested that private property or government regulation is needed to govern the commons. Economists generally prefer private property institutions (Posner 1998), although the efficacy of private property depends critically upon the costs of creating, monitoring, and enforcing such rights (Lueck 1995, Anderson and Hill 1975, Demsetz 1967). Government regulation often entails direct costs as well as inefficiencies attributable to rent-seeking by those interests affected by regulation. Although private property regimes often ameliorate the tragedy of the commons, shared governance institutions can maximize utility in a range of circumstances depending upon the cohesion and history of the community affected and the nature of the resources in question (Libecap 1994, Ellickson 1991, Ostrom 1990, Rose 1986).

1.4 Personhood

The personhood justification for private property, derived from Kant’s Philosophy of Law and Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, has been elaborated in modern legal discourse in the work of Radin (1982, 1993). ‘The premise underlying the personhood perspective is that to achieve proper development—to be a person—an individual needs some control over resources in the external environment. The necessary assurances of control take the form of property rights’ (Radin 1982). The personhood justification for private property emphasizes the extent to which property is personal as opposed to fungible: the justification is strongest where an object or idea is closely intertwined with an individual’s personal identity and weakest where the ‘thing’ is valued by the individual at its market worth. The personhood justification for private property is limited and highly subjective (Schnably 1993).

1.5 Distributive Justice

Theories of distributive justice seek to allocate society’s resources on the basis of just principles. The process of determining such principles is the focus of considerable debate. Many theories incorporate utilitarian and Lockean principles. In perhaps the most influential work on distributive justice of the past century, Rawls (1971) offers an ‘ideal contractarian’ theory of distributive shares in which a just allocation of benefits and burdens of social life is determined by what rational persons would choose from behind a ‘veil of ignorance,’ which prevents them from knowing what abilities, desires, parentage, or social stratum they would occupy. Rawls concludes that people behind such a veil would adopt what he calls the ‘difference principle’: ‘primary goods’—not only wealth, income, and opportunity, but also bases of self-respect—would be distributed to the maximal advantage of a representative member of the least advantaged social class. Rawls (1993) emphasizes that the difference principle does not call for simple egalitarianism but rather measures to assure that ‘the basic needs of all citizens can be met so that they can take part in political and social life.’

1.6 Civic Republicanism

Republicanism rejects the view that individuals are wholly autonomous and that the public interest is just the aggregation of individual preferences. Republicanism stresses civic virtue and the role of participation in public discourse as essential to the realization of the common good. Civic republicanism relies upon the propertied independence of its citizens. Such ownership of capital affords citizens the competence to engage in meaningful discourse and protects against the subversion of democracy by a wealthy oligarchy or an aggressive state (Simon 1991).

1.7 Marxist Theory

Karl Marx viewed human history as an evolutionary process of class struggle leading, ultimately, to a classless society (communism) in which the state will wither away. In the capitalist phase of this evolution, private property provides the basis for the most important social relation: ownership of the means of production. According to Marx, the class owning the means of production (bourgeoisie) acquires the property (capacity to work) of the labor class (proletariat) through the employment relation, thereby obtaining exclusive control of and hence power over the worker class. Such subordination, exploitation, and alienation sow the seeds of revolution, leading to the establishment of a proletarian dictatorship, socialism (productive resources owned by workers through participatory institutions), and eventually communism, a classless society without exploitation or inequalities in which property in land and rights of inheritance are abolished (Marx and Engels 1848).

1.8 Ecological Theories

As understanding of the connections between technology, land development, and the environment has deepened, many environmental scholars have increasingly viewed private property rights more skeptically (Sax 1983). Traditional reformist theories— which are anthropocentric in nature and draw heavily upon utilitarian and other traditional philosophical frameworks—favor internalization of the adverse impacts of development (Menell and Stewart 1994), Ellickson (1977, 1973). Building upon Leopold’s (1949) call for a land ethic which seeks to ‘preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty to the biotic community,’ Freyfogle (1996), Sprankling (1996), and Sax (1993) propose a shift away from private property toward greater regulation and coordination of land and natural resource development. At the other extreme, Anderson and Leal (1991), drawing upon property rights and public choice literatures, advocate complete reliance on private property and free market principles as the best institutional choice to address substantially all environmental problems. Menell (1992) highlights the institutional limitations of both extremes and urges careful attention to the strengths and limitations of the broad spectrum of institutional alternatives in governing resources.

1.9 Pluralist And Hybrid Theories Of Property Rights

The insights of the many philosophical perspectives have led some scholars to synthesize multiple strands into new and comprehensive theories for justifying and evaluating property. Munzer (1990), for example, constructs a theory of property built upon principles of utility and efficiency, justice and equality, and rewards based on labor. Simon (1991) synthesizes civic republicanism and socialism to advocate an intermediate form of property emphasizing enterprise and community-based democracy (cf. Hansmann 1996), offering a utilitarian explanation for worker owned and managed firms and organization).

2. The Emergence Of Private Property Rights

Although no single philosophical theory provides a complete explanation for private property rights, utilitarianism has emerged as the dominant framework for understanding property rights systems. In a seminal article, Demsetz (1967) posited that private property regimes develop to internalize externalities. As the benefits of internalizing externalities rise (e.g., where a common resource becomes more valuable) or the cost of internalizing externalities fall (e.g., as technology reduces the costs of fencing or monitoring property rights), private property systems emerge to promote efficient management of the resource. As support for this thesis, Demsetz cites anthropological evidence suggesting that native Americans established private hunting territories following the arrival of Europeans and the development of the fur trade. By spurring the hunting of beavers, the fur trade threatened the productivity of this renewable resource, thereby creating social pressure to institute property rules that internalize the effects of resource exploitation.

Demsetz’s theory explains the emergence of private property institutions across a broad range of contexts, including air (sulfur oxide emissions in the United States), water allocation, fishing, telecommunications spectrum, wetlands, roads (tolls), trademarks (causes of action for diluting famous marks), and publicity (commercial exploitation of a person’s image, likeness, or voice). Nonetheless, by focusing exclusively upon private property institutions, Demsetz’s theory overlooks much of the richness of property institutions and the complex social processes that affect their evolution. Libecap (1994), Ostrom (1990), Ellickson (1991), Rose (1986), and others contribute to the explication of a broad spectrum of property institutions lying between the poles of pure private property and the commons where informal and shared governance emerge and succeed in allocating resources.

The emergence and nature of property rights also reflect the political economy driving the legislative process and government agencies that administer property rights (Buchanan and Tullock 1962). Interest groups tend to form in those areas where government policies create concentrated benefits or impose concentrated costs (Olson 1965). Laws and agencies creating or affecting property rights (e.g., through regulation) attract substantial rent-seeking activity. Thus, the design of such property regimes often reflect political, as well as economic, considerations.

3. Evolution Of Jurisprudential And Analytical Conceptions Of Property

Although property rights are as old as human civilization, the modern jurisprudential conception of property traces its roots to the agrarian and early mercantilist economies that developed during the decline of feudalism. Sir William Blackstone (1765), author of the first widely accepted legal treatise on English law, regarded property as an absolute right

which consists in the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of all acquisitions, without any control or diminution, save only by the laws of the land …

So great moreover is the regard of the law for private property, that it will not authorize the least violation of it; no, not even for the general good of the whole community …

Although some have questioned Blackstone’s rigor and cogency (Burns 1985) few doubt his influence upon the jurisprudence of property in England and America. Maine (1861) reinforced the superiority of private property institutions through his historical account of the progress of civilization from primitive forms of shared ownership among kinship groups (status) to individual ownership and alienability of property interests (contract).

The industrial revolution and the shift from an agrarian economy to urban and other community structures changed the ways in which land and other resources were owned and exploited. The desire to restrict land through contract pushed courts to liberalize constraints on non-possessory interests, presaging the disintegration of the unitary bundle of sticks. Property came to be seen increasingly as a malleable concept that could be tailored to serve utilitarian purposes.

In the early twentieth century, Hohfeld (1913) developed a detailed descriptive framework for capturing the richness of legal rights reconceptualizing property as relationships among people relative to things. Recognizing four primary legal entitlements— rights, privileges, powers, and immunities—Hohfeld postulated four basic legal relations (‘correlatives’): ‘right–duty,’ ‘privilege–absence of right,’ ‘power– liability,’ and ‘immunity–disability.’ Hohfeld provided the vocabulary and structure for representing the complexity of property relations—bundles of rights (and relations)—as well as the conceptual menu from which legislatures and courts could craft property rights.

Blackstone’s conception of property as an inviolate, unified bundle of rights came under increasing assault with the proliferation of zoning and other public land use controls upon private property rights and the expansion of the role of government at all levels following the New Deal in the USA. Property rights, like much of the law governing the legal relations, came increasingly within the purview of political institutions, and accordingly gave way to the instrumentalist (utilitarian) nature of politics.

In a seminal article, Coase (1960) developed a new, instrumentalist framework for analyzing property rights. In much the way that a frictionless surface enables physicists to isolate and study the laws of physics, Coase hypothesized a world of zero transaction costs (costless bargaining and enforcement of agreements), which provided valuable insights into the interplay of legal and market institutions. Coase demonstrated that in a world of costless transactions, an efficient allocation of resources will result regardless of how property rights are initially allocated. The desire of conflicting property owners to maximize their joint profit will lead them to bargain to an efficient allocation of resources. The initial allocation of entitlements will affect the distribution of wealth, but not the total level of wealth.

As with the frictionless surface, Coase recognized that costless transactions do not exist in the real world. His article fueled a deluge of scholarship exploring the implications of costly transactions for the allocation and design of property rights. Building upon Coase’s construct, Calabresi and Melamed (1972) developed a framework that divides the analysis of property rights into two inquiries: (1) how should property rights be allocated; and (2) how should such entitlements be enforced—by a property rule (enabling property owners to enjoin interference with their entitlement and requiring consent for violation or transfer of the entitlement), a liability rule (allowing property owners court-determined damages for invasion of their property right, as in the case of eminent domain), or by a rule of inalienability (preventing transfer of a property right, as with prohibitions on the sale of body parts).

Calabresi and Melamed propose that entitlements and enforcement rules be based on economic efficiency, distributional goals, and other considerations of justice. Where transactions are costly, entitlements should be allocated so that the party who is best able to minimize harm (the least cost avoider) bears responsibility for the harm in order to promote economic efficiency. With regard to the enforcement of entitlements, Calabresi and Melamed demonstrate that the use of liability rules can minimize the costs of making an erroneous decision about the allocation of entitlements where transactions are costly. Subsequent scholars have refined and extended the framework and applied it in a range of contexts (Symposium 1997, Kaplow and Shavell 1996, Merges 1996, Radin 1996, Krier and Schwab 1995, Rose-Ackerman 1985, Polinsky 1980, Ellickson 1977, 1973).

In a provocative essay published in the early 1980s, Grey (1980) argued that the field of property ‘ceases to be an important category in legal and political theory’ as a result of the ‘disintegration’ of the conception of property. In his view, the dividing of property ownership into a ‘bundle of rights’ and the development of differing conceptions of property across disciplines has ‘fragmented’ property theory ‘into a set of discontinuous usages.’ Numerous scholars have questioned Grey’s claims on a range of bases (Munzer 1990), yet the observation that provided the point of departure for Grey’s essay, the ‘disintegration’ of property, resonates today. Property has lost the simplicity of Blackstone’s conception—unitary, exclusive, and omnipotent control—but a new conception of property integrating the many institutional structures governing resources, the cultural contingency of governance regimes, and the dynamism of governance institutions has emerged.

4. Property As A Triadic Relation

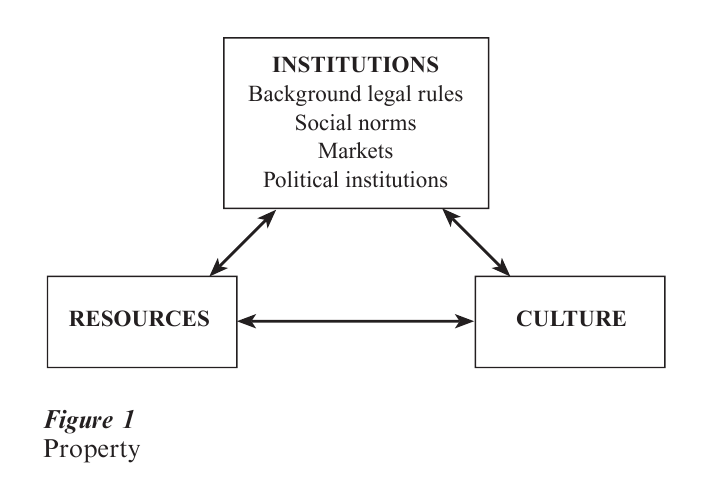

Menell (2001) and Dwyer and Menell (1998) present property as a dynamic system comprising three components: resources, institutions, and culture. Resources may be governed by background legal institutions (such as common law rules, or in civil law regimes, codes), social norms, markets (contractual agreements supported by the background legal institutions), political institutions (e.g., zoning), or some combination thereof. At any point in time, the mix of governance rules and institutions reflects the nature of the resources governed and the society or culture (knowledge, values, cohesion, technology) in which the resources are situated. Thus, in smaller, more cohesive social settings, we might observe more commonly particular resources are governed through social norms or other common property institutions whereas the same resources might be governed through formal private property institutions in a larger, more heterogeneous community. In this way, the triadic framework captures the economic and cultural dependency of resource governance as well as the richness of property regimes.

The triadic conception of property also incorporates the dynamic nature of resource governance. As reflected in Fig. 1, the framework incorporates causal connections and feedback mechanisms. Changes in the society (such as the value attributed to the protection of endangered species or technological advances reducing the costs of monitoring private property rights) generate changes in the design and mix of governance institutions. Such changes, by affecting the resource base, may generate further reactions within the overall system. The system may also be affected by external shocks, such as charges in the larger political atmosphere. Demsetz’s (1967) positive account represents a special case of this dynamic process, but the triadic relation generalizes the dynamism of institutional evolution to account for a broader mix of governance institutions.

5. New Frontiers

Notwithstanding the settlement of substantially all significant land masses on the planet, the frontiers of property continue to expand and evolve. Among the most important resources in today’s economy are intangibles—ideas, genetic code, cyberspace, telecommunication spectrum (Merges et al. 2000). The internet has significantly expanded opportunities to distribute expressive works, but has also threatened the ability of copyright owners to control their works. This new medium has reshaped perceptions about rights to reproduce and distribute expressive works. Advances in bioscience have spawned disputes over rights and control of human genetic code, cell lines, and indigenous plants. And even in the more conventional realm of land management, increasing pressures on natural resources, greater knowledge of ecosystem effects, and changes in attitudes toward the environment continue to alter the balance among private property rights, public ownership, and regulation (Dwyer and Menell 1998, Menell and Stewart 1994). Public rights in artistic treasures, historical documents, architectural works, archeological discoveries, and scholarly research present a further set of challenges for a system of governance built significantly upon a foundation of private property rights (Sax 1999). Just as the advent of rights in government benefits expanded our conception of property four decades ago (Reich 1964), advances in technology and changing social values continue to expand and alter our conception of property.

Bibliography:

- American Law Institute 1936 Restatement of the Law of Property. American Law Institute Publishers, St Paul, Minnesota

- Anderson T L, Hill P J 1975 The evolution of property rights: A study of the American West. Journal of Law and Economics 12: 163–79

- Anderson T L, Leal D R 1991 Free Market Environmentalism. Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, San Francisco

- Bentham J 1789 An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

- Becker L 1977 Property Rights: Philosophic Foundations. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

- Blackstone W 1765 Commentaries.

- Buchanan J, Tullock G 1962 The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

- Burns R P 1985 Blackstone’s theory of the ‘absolute’ right of property. University of Cincinnati Law Review 54: 67–86

- Calabresi G, Melamed A D 1972 Property rules, liability rules, and inalienability: One view of the Cathedral. Harvard Law Review 85: 1089–128

- Coase R 1960 The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics 3: 1–28

- Demsetz H 1967 Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 57: 347–58

- Dwyer J P, Menell P S 1998 Property Law and Policy: A Comparative Institutional Perspective. Foundation Press, Westbury, NY

- Ellickson R C 1973 Alternatives to zonoing: Covenants, nuisance rules, and fines in land use controls. Uni ersity of Chicago Law Review 40: 681–781

- Ellickson R C 1977 Suburban growth controls: An economic and legal analysis. Yale Law Journal. 86: 385–511

- Ellickson R C 1991 Order Without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Ellickson R C 1993 Property in land. Yale Law Journal 102: 1315–1400

- Epstein R A 1979 Possession as the root of title. Georgia Law Review 12: 1221–43

- Epstein R A 1985 Taking: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Freyfogle E T 1996 Ethics, community, and private land. Ecology Law Quarterly 23: 631–61

- Grey T 1980 The disintegration of property. Nomos 22: 69–85

- Hansmann H 1996 The Ownership of Enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Hardin G 1968 The tragedy of the commons. Science 162: 1243–8

- Hohfeld W N 1913 Fundamental legal conceptions as applied in judicial reasoning. Yale Law Journal 23: 16–59

- Kaplow L, Shavell S 1996 Property rules versus liability rules: An economic analysis. Harvard Law Review 109: 713–90

- Krier J, Schwab 1995 Property rules and liability rules: The cathedral in another light. New York University Law Review 70: 440–83

- Leopold A 1949 A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press, New York

- Libecap G 1994 The conditions for successful collective action. Journal of Theoretical Politics 6: 569–98

- Locke J 1698 Second Treatise of Government.

- Lueck D 1995 The rule of first possession and the design of the law. Journal of Law and Economics 38: 393–436

- Maine H S 1861 Ancient Law.

- Marx K, Engels F 1848 The Communist Manifesto.

- Menell P S 1992 Institutional fantasylands: From scientific management to free market environmentalism. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy 15: 489–510

- Menell P S 2001 Property as a triadic relation. (manuscript in progress)

- Menell P S, Stewart R B 1994 Environmental Law and Policy. Little, Brown, Boston, MA

- Merges R P 1996 Contracting in liability rules: Intellectual property and collective rights organizations. California Law Review 84: 1293–393

- Merges R P, Menell P S, Lemley M A 2000 Intellectual Property in the New Technological Age, 2nd edn. Aspen Law & Business, New York

- Munzer S R 1990 A Theory of Property. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Nozick R 1974 Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Olson M Jr 1965 The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Ostrom E 1990 Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Polinsky A M 1980 Resolving nuisance disputes: The simple economics of injunctive and damage remedies. Stanford Law Review 32: 1075–112

- Posner R 1998 Economic Analysis of Law, 5th edn. Aspen Law & Business

- Radin M J 1982 Property and Personhood. Stanford Law Review 34: 957–1015

- Radin M J 1993 Reinterpreting Property. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Radin M J 1996 Contested Commodities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Rawls J 1971 A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Rawls J 1993 Political Liberalism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Reich R 1964 The new property. Yale Law Journal 73: 733–87

- Rieser A 1997 Property rights and ecosystem management in US fisheries: Contracting for the commons? Ecology Law Quarterly 24: 813–32

- Rose C 1985 Possession as the origin of property. University of Chicago Law Review 52: 73–88

- Rose C 1986 The comedy of the commons: Custom, commerce, and inherently public property. University of Chicago Law Review 53: 711–81

- Rose C 1987 ‘Enough, and as good’ of what? Northwestern University Law Review 81: 417–42

- Rose C 1998 The several futures of property: Of cyberspace and folk tales, emission trades and ecosystems. Minnesota Law Review 83: 129–82

- Rose-Ackerman S 1985 Inalienability and the theory of property rights. Columbia Law Review 85: 931–69

- Ryan A 1984 Property and Political Theory. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Sax J L 1983 Some thoughts on the decline of private property. Washington Law Review 58: 481–96

- Sax J L 1993 Property rights and the economy of nature: Understanding Lucas . South Carolina Coastal Council, Stanford Law Review 45: 1433–55

- Sax J L 1999 Playing Darts with a Rembrandt: Public and Private Rights in Cultural Treasures. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

- Simon W H 1991 Social republican property. UCLA Law Review 38: 1335–413

- Schlatter R 1951 Private Property: The History of an Idea. George Allen & Unwin

- Schnably S J 1993 Property and pragmatism: A critique of Radin’s theory of property and personhood. Stanford Law Review 45: 347–407

- Sprankling J P 1996 The antiwilderness bias in American property law. University of Chicago Law Review 63: 519–89

- Symposium 1997 Property rules, liability rules, and inalienability: A twenty-five year retrospective. Yale Law Journal 106: 2083–213

- Waldron J 1988 The Right to Property. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK