Sample Mobilization Of Law Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Theories of mobilizing the law try to explain under which conditions problems come to be defined and socially accepted as legal issues, and under which conditions they are taken to lawyers and courts. They look at the process of (a) moving from perception to motivation, (b) the interaction of parties and their strategies, and (c) finally at courts as institutions which define the frontiers of law.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Access To Courts As A Process

‘Naming, blaming, and claiming’ are the catchwords by which Felstiner et al. (1981) describe the steps of framing social conflicts in legal terms. They discuss how experiences come to be felt as injurious (naming), how a party might be singled out as responsible (blaming), and under which conditions claims might be formulated on the basis of these experiences. They turn around the assumption of market researchers who identified ‘unmet legal needs’ (Curran 1977, ABA 1994) by surveying people for injurious experiences which in the minds of lawyers would give rise to a legal claim. In fact, claiming does not automatically follow upon naming and blaming (Genn 1999). A representative British survey documents the various strategies of self-help people pursue before mobilizing the the law (Blenn 1999). It shows the importance of informal access to law for which Britain with its citizens’ advice bureaux and legal aid provisions offers a wide range. People make choices: the greater the interest in a continuous social relation, the higher social costs would be. In a survey of everyday injurious situations which people encounter in a German modern city (such as Frankfurt), Hanak et al. (1989) show that only a tiny fraction of all potential legal disputes actually reach lawyers or appear in court. ‘Naming’ and blaming are everyday reactions to disappointment and injury, but ‘claiming’ is a far rarer phenomenon. To preserve ongoing relations, it can be entirely ‘rational’ to avoid engaging in legal steps of any kind. Consequently, Hanak et al. declare people who directly frame their social problems in legal terms as ‘socially incompetent.’

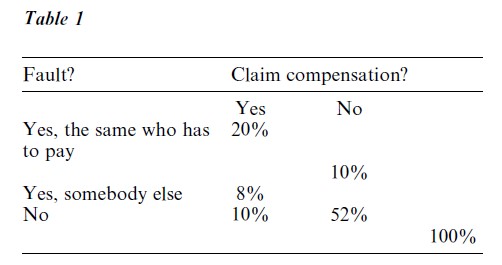

An empirically well-documented example is given by the selectivity with which people claim compensation for accidents: Harris et al. (1983) sampled 3,600 people in England who had been absent from work for more than two weeks during the previous 12 months: while 60 percent said that they had been seriously ill, 34 percent blamed their absence on an accident, of which 90 percent occurred at home or during their free time, one tenth during work, and every fifth as traffic accidents. The point of the study is that ‘blaming’ others for causing an accident is largely independent of whether victims proceeded to ‘claiming’ compensation. Accidents at home or in free time might just as well be caused by others, but they would be seen as mishaps without legal consequences, while accidents at work which might be seen as ‘one’s own fault’ would nevertheless give rise to claims for compensation. The explanation lies in the everyday logic of the social relation: while a claim for injury which remains in the sphere of personal social relations is avoided because it would outweigh the social costs of alienating that relation, a legal claim is easily made if covered by employers or other kinds of insurance. Often the claim consciousness works back into the perceptions: framing in terms of legal liability colors the perception of social fault. See Table 1.

Accidents are easily identifiable as a basis for damage compensation. Other potential sources of liability claims are less obvious: damages in consumer protection, medical malpractice, and tobacco litigation were discovered (and as liability claims ‘invented’) by pioneering lawyers and consequently advertised to help people climb over the barriers of mobilizing the litigation process. From the point of view of the providers of legal services it becomes a marketing problem that only a tiny fraction of all potential legal disputes actually reach lawyers or appears in court. However, people do not always have a choice but to enter into legally defined handling of situations. Frequently it is the other party who invokes the law. In dealing with them, people mobilize the law defensively rather than proactively (Black 1973), and they are forced to do that the more they are interacting with formal organizations and in anonymous situations. Also, not all social relations are designed for continuity. The more urban and mobile people get, the more they handle incidental and anonymous social relations. After a traffic incident or as clients of a big organization, parties are confronted with predefined ways of dealing with conflicts. Especially formal organizations and government agencies pattern their relations in legal terms to begin with. The bigger they are, the more likely they contract with employees, partners, or clients in written terms, and these in turn are bound by general regulations. Therefore there is no choice but to take legal steps. Black (1973) generalizes these findings into the proposition ‘the greater the social distance, the more law.’

Thus, if asking why the frequency of litigation is rising in all modern societies, the explanation has to move from micro-sociology to macro-sociological conditions. A number of trends come together to increase ‘judicialization’ of many walks of life, be they world-wide such as urbanization, or specific to certain societies and to lower social classes, such as welfare state systems which bind people’s life chances into dependency. In other countries and in the middle classes it may not be the state but rather private insurance systems which increase the dependence of formal bureaucracies—the trend remains that the coverage of life risks is less provided by informal care and personal ties but rather contracted and insured with large formal organizations. Culture critics (like Habermas 1981) have called this trend of modernity ‘legal terms patterning the modern lifeworld.’

2. Strategies Of Mobilizing The Law: Enforcing, Mediating, Adjudicating

The perspective of social actors, taken in the above studies, can be contrasted with that of legal institutions. Government, by definition, regulates by statutory law, but if state regulation is compared with the contract terms of big organizations, there appears to be not much difference between being a citizen of the regulative state or a client of organized enterprises. For individual actors, the difference from state regulation lies in the initial choice and the chances for exit which markets might offer, but once chosen many long term contracts turn out to be just as bureaucratic and regulatory, while for multinational actors even the regulatory regimes of states appear as a matter of choice. The likelihood of social relations being defined in legal terms depends on the size of organizations and the degree of their formalization.

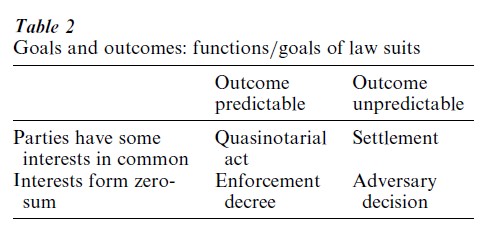

However, within a more or less formal relationship actors do differ in the way they bring grievances forward. Disputes are seldom purely adversary; often both parties have at least some interests in common. That is even the case when parties battle furiously as in a divorce suit: typically the parties have at least one goal in common—the desire to separate. In fact, most divorces are settled; in only a minority is there a battle about the terms of separation. The same is true for other constellations where courts are invoked to set the terms of separation. Labor dismissal and landlord– tenant conflicts seldom try to regulate the terms of an ongoing relationship; they typically end with a settlement on how to part. As most countries require a court decision for divorce, parties regularly appear with a settlement negotiated in advance; they need the court to function as quasi-notary. The largest number of court cases, however, concern undisputed claims: the plaintiff simply needs a court decree to force the defendant to comply; the defendant may not even show up and the case ends with a default judgment. In most courts the dispute that is fought all the way to an adversary decision forms the minority of cases (Blankenburg 1980/95) (see Table 2).

The distribution of court functions varies with the issue at stake. Miller and Sarat (1980 81) depict the different distributions as pyramids. Discrimination grievances are very frequent, but rarely is a lawyer consulted by the aggrieved; only 8 out of 1,000 appear in court, thus the top of the pyramid gets extremely thin. Tort more often develops into a dispute, but still not as often as post-divorce cases which are regularly fought all the way to an adversorial decision—thus the top of the pyramid covers 45 percent of the baseline.

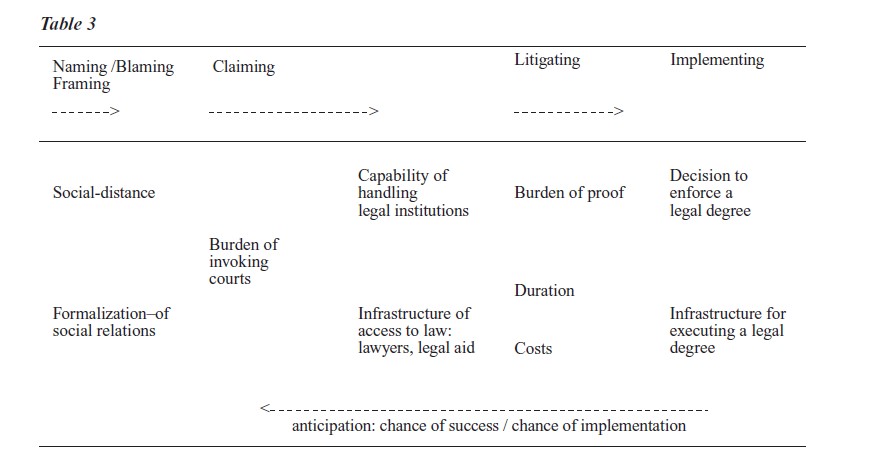

However, court decisions are not the end of the conflict story. Implementation studies after litigation have shown that parties who won in court do not necessarily make use of the entitlement they have fought for, either because the losing party is incapable of paying or satisfying the claim, or because the winner in court is using the entitlement for out-of-court negotiations in a wider social context than that of the court verdict. Invoking a law suit means entering an interaction system with the roles of several actors being determined by procedure: plaintiffs and defendants are determined by their proactive, respectively defensive strategies; decision makers by the requirements of due process which implies a highly dramatic presentation of impartiality. Actually, the strategic game starts before the suit itself: a decisive factor bearing on the likelihood of whether legal institutions are invoked at all is the rule on who has the burden of invoking the law. Litigation costs time and money: the procedural losses may outweigh the gain of even a favorable verdict. Plaintiffs have to assess their evidence, anticipate the strategy of the defendant, and evaluate the chances of being able to implement a legal title, should they get it. Basic preconditions for involving a court are already prescribed in the legal construction underlying social relationships: if the party which has the ‘burden’ of invoking the court has insufficient legal expertise or hesitates for motivational reasons, the other party can exploit the situation until challenged. The asymmetric party constellation in the majority of court cases suggests such exploitation of mobilization thresholds on a massive scale: most plaintiffs before civil courts are business firms and other organizations, while the majority of defendants are private parties. Organizations that routinely deal with legal problems can often turn the differential access conditions to their advantage.

Anticipation of the potential costs and the possible gains of a procedure adds to the advantages of the repeat player in court (Galanter 1974). Good lawyers and experienced court users will have better foresight than others will. Whether parties go all the way to a court decision or even an appeal depends on continual re-assessment, anticipating not only the chances of success, the costs of the procedure and the opportunity costs, but also the assessments of the other party likewise anticipating its chances. The scheme in Table 3 helps to organize the variables which are relevant in the process.

Assessing the juridical configuration in different social fields is daily work for lawyers. Their strategies and those of their clients interact within the frame of the given legal order. Their assessments vary with national jurisdictions and possibly local regimes. Comparing litigation frequencies of similar disputes between countries and states (or even court districts) reveals the overriding impact of legal regimes. To compare legal cultures, researchers look at similar grievances, like the regulation of injury and damage after accidents. The most obvious example might be traffic accidents: traffic tort in some legal cultures frequently entangles the victims in legal procedures, while in others insurance companies regulate largely outside the courts. Comparison of American with Japanese accident regulation demonstrates that it is not cultural mentality or personal skill which explains how the Japanese avoid legal costs, but rather the legal and institutional conditions which frame their avoidance of litigation (Haley 1978). The same can be said of the infrastructure of avoidance that explains why the Dutch litigate considerably less frequently than the neighboring Germans: accident victims in these countries hardly differ in conflict mentality nor does their tort law differ. The explanation for different litigation frequencies lies in institutional conditions of the legal regime: burdens of proof, lawyer fees, legal cost insurance, and the availability of alternative modes of regulation (Blankenburg 1994). Similar comparisons can be drawn with respect to other comparable disputes: divorce, employment dismissal, landlord– tenant disputes, or debt enforcement need to be dealt with by courts in some countries while others treat them as routine regulation, reserving litigation in court as a last resort for a few, serious cases.

3. Frontiers Of The Law: Test Cases And Strategies Of Mobilizing Rights

If in the eyes of the occasional litigant ‘serious’ refers to the stakes which are at dispute in a particular case, to the legal profession and the legal academy, serious implies that there are principle questions of law to be resolved. The greater chances of repeat players (RPs ) to win in court (Galanter 1974) are amplified in the long term: repeat players can pursue strategies over a series of cases, and they can aim at precedents and high court decisions which change the interpretation of the law. The strategic advantage enables big players in courts, such as insurance, banking, and manufacturing corporations to set the terms of statutes and standard contracts in their favor. Occasional litigants (one shooters (OSs) in Galanter’s (1974) terms can only fight the legal battle by organizing as interest groups and getting together for class actions. Interest groups implicitly threaten with a potential of future litigants. Parties with especially diffuse interests, such as consumers, parties, or victims of environmental damage, whose single case might not be worth fighting a legal battle, can see their strategic chances in mobilizing courts rather than trying to win in the legislative process.

A number of institutional features favor such public interest strategies among American lawyers and in American courts: the tradition of case law, the instruments of class action, the possibility of contingency fees, and the chances for popular support by juries have made American lawyers especially inventive in thinking up novel sorts of claims, mobilizing collective expectations, and framing them in legal terms. Media coverage of pioneering cases like the asbestos and tobacco liability litigation have made their way around the world. These claims have been spectacularly successful in changing the perception and the legal liability of producers and service providers in North America and, consequently, also in continental legal systems. Another feature of the American legal system which has turned courts into a law-making forum has been the possibility of Supreme Courts to set aside statutory law by the application of human rights and constitutional jurisprudence. Many continental systems have introduced similar possibilities of overturning legislative codes by establishing constitutional courts—the collapse of fascist, communist, and apartheid regimes, with their experience of abuses of legal institutions, have facilitated such institutions. Mobilizing the global forum of human rights has opened a wave of innovation challenging traditional codes of law, and turning courts into law making rivals of parliamentary legislation (Shapiro 1980).

Of course, strategies of mobilizing courts for pioneering cases are even more demanding than the mobilization of courts by occasional litigants. The selectivity of invoking legal institutions on all levels makes us aware of a general feature of any kind of law: so long as actors comply with legal norms we cannot know whether conformity reflects the impact of law or is motivated by custom, by their present interests, or mere inertia. Under conformity, law rests dormant; it manifests itself only under special circumstances of deviation and disagreement when law is mobilized explicitly (Geiger 1947). Paradoxically, one might conclude that law works best if it does not need to be mobilized.

Bibliography:

- ABA(American Bar Association) 1994 Legal Needs and Civil Justice. ABA, Chicago

- Black D 1973 The mobilization of law. Journal of Legal Studies 2: 125

- Blankenburg E 1980/95 Mobilisierung des Rechts. Springer, Berlin

- Blankenburg E 1994 The infrastructure of avoiding civil litigation. Law and Society Review 28: 789–808

- Blankenburg E, Voigt R, (eds.) 1987 Implementation von berichtsentscheidungen Jahrbuch fur Rechtstheorie und Rechtssoziologie 11

- Curran B 1977 The Legal Needs of the Public. Chicago

- Felstiner W, Abel R, Sarat A 1981 The emergence and transformation of disputes. Law and Society Review 15: 631

- Galanter M 1974 Why the haves come out ahead. Law and Society Review 9: 95

- Geiger T 1964 Vorstudien zu einer Soziologie des Rechts. Luchtenband

- Genn H G 1999 Paths to Justice. Hart, Portland, Oxford, UK

- Habermas J 1981 Theorie des kommunikati en Handelns. Frankfurt, Germany, Vol. 2, Chap. 6

- Haley J O 1978 The myth of the reluctant litigant. Journal of Japanese Studies 359–90

- Hanak G, Stehr J, Steinert H 1989 Argernisse und Lebenskatastrophen. AJV, Bielefeld

- Harris D et al. 1984 Compensation and Support for Illness and Injury. Oxford, UK

- Shapiro M 1981 Courts: A Comparative and Political Analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago