Sample Cognitive Anthropology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Cognitive anthropology attempts to link anthropology with the cognitive sciences. Culture, as one of anthropology’s central objects of research, has an effect in two respects: on the one hand, in a material sense in the form of cultural phenomena, on the other hand, mentally, in the form of cultural contents. Cultural contents are based on mental representations. While cultural phenomena are public and thus easy to document ethnographically, cultural contents are not directly accessible since mental representations cannot be observed. What actually happens inside people’s heads is the object of research of the cognitive sciences. Cognitive sciences see the human experience of reality and human thinking as acts of processing information. In addition to the study of perception, mental representation, and memory, the objective is to make transparent those mental faculties that enable all humans to internalize the social and cultural characteristics of the society into which they are born. But these are also central topics of anthropological research.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. From Ethnoscience To The Cognitive Sciences

The year of birth of the ‘cognitive revolution’ in which, apart from social anthropology, various human sciences participated, to some extent independently of each other, is considered to be 1956. That year, at a conference on information theory at the Massachu-setts Institute of Technology, Newell and Simon presented a paper on computer programs, Miller presented his famous treatise The Magical Number Se en, and the 28-year-old Chomsky read excerpts from his thesis Three Models of Language. In the same year, Bruner’s book A Study of Thinking was published and two anthropologists, Goodenough and Lounsbury, published the first two programmatic articles on cognitive anthropology, Componential Analysis and the Study of Meaning and A Semantic Analysis of the Pawnee Kinship Usage.

With cognitive anthropology or, more precisely, with the ethnoscience phase of cognitive anthropology, a new field of research came to the fore. Its goal was to describe other cultures in their own conceptualization, that is, in emic terms or from the inside. Different cultures categorize the world differently and apply a different type of logic in dealing with their environment. This difference should be recorded as it reveals different cognitive worlds. The underlying question was an old one: What does the ‘order out of chaos’ look like? More precisely, the basic questions were ‘How do other cultures label the things in their environment, and how are these labels related to each other?’ This according to the assumption that with the help of cultural phenomena the cultural contents, and thus the mental representations, could also be documented.

1.1 Three Premises

One can argue that three premises formed the back-ground to this ambitious program:

1.1.1 Premise 1: Culture is common (shared) know-ledge. A highly significant definition of culture was coined by Goodenough: ‘A society’s culture consists of whatever it is one has to know or believe in order to operate in a manner acceptable to its members, and to do so in any role that they accept for any one of themselves. … It is the forms of things that people have in mind, their models for perceiving, relating, and otherwise interpreting them. … Culture does not exist of things, people, behaviour, or emotions, but in the forms or organizations of the things in the minds of people’ (Goodenough 1957, pp. 167–8).

Seen in this way, culture is a mental phenomenon.

1.1.2 Premise 2: Knowledge has the form of a cultural grammar. Anthropologists must, on the basis of the statements made by their informants, inductively discover this abstract and shared knowledge as a systematic mental representation. In principle, they can, in order to do so, limit themselves to one person, as applies when learning a foreign language, where at first sight it suffices to have one speaker at one’s disposal. The knowledge system of a culture is under-stood to be a conceptual model which embraces the organizational principles of the culture and the behavior of its members. The model is, so to speak, a cultural grammar.

1.1.3 Premise 3: Language is the best means of access to mental phenomena. With the reduction of chaos, certain phenomena and characteristics are selected from the environment as being significant, named, and given a classificatory meaning. The main (but not the only) proof of the existence of a category is its label.

The equation of culture and knowledge proved to be very fruitful. In the 1960s, ethnoscience experienced rapid success. Innumerable studies were published— which was to be expected—about terminologically densely structured individual fields, such as those on kinship, colors, ethnozoology, ethnobotany, or illness. One succumbed, as it were, to the great theoretical temptation to reduce complex and ostensibly heterogeneous things to a few rules (inclusion, exclusion, and intersection) and to present them as elegant models (taxonomy, paradigm, see below) which were looked upon as mental representations of individuals.

At the beginning of the 1970s, however, only a very few studies appeared, and Keesing (1972, p. 229) was justified in starting a paper with the sentence: ‘Tell me, whatever happened to ethno-science?’ Here lies the irony: when, at the end of the 1950s, ethnoscience took over this model from linguistics and it became the focal point in the 1960s, it had already been swept aside in linguistics itself by Chomsky’s new generative linguistics.

The result was an opening up and turning towards modern trends in neighboring disciplines. Computer science proved to have particularly strong influence; when the first computer programs appeared which played chess, the question arose, ‘If computers can have programs, why can’t people, too?’ In endeavoring to reproduce human cognitive representations in the model, cognitive anthropology adopted the ‘information-processing approach.’ In so doing, the assumption (at that time) that cognitive processes follow the same pattern universally, whether in humans, animals, or the machine (in other words, that the software is the same everywhere, irrespective of the hardware in which it is processed) was, from a philosophical point of view, highly explosive.

1.2 Revised Premises

As a consequence, the three premises of ethnoscience were reconsidered and extended; the emphasis turned to where knowledge is sought and how it is represented.

1.2.1 Revised Premise 1: Turning towards the individual. Attention at the end of the twentieth century was no longer focused on the collective knowledge system as the whole of a culture (as representation collective in the sense of Durkheim), supposed to be recorded as the ideal type, but on the scattered, variable knowledges acquired, stored (memorized), and applied by individuals in their everyday life. The focus shifted, because it was recognized that inferences cannot be directly drawn from cultural phenomena and linguistic material in order to elaborate individual cognitive processes or representations.

1.2.2 Revised Premise 2: Operationalization instead of categorization. As soon as knowledge is no longer defined as an isolated, static system (that is, simply as grammar) but as something which is evident (ver-bally or nonverbally) in everyday use by individuals, it becomes clear that many categories and semantic fields have no fixed boundaries, and cannot be de-fined in the classical sense (fuzzy sets). They are now also grouped according to what a person can do in daily life (‘taskonomy’ instead of taxonomy) or else according to prototypes (best example from a category). It is everyday cognition that a housewife needs when she shops, a milkman when he distributes dairy products to his customers according to a certain pat-tern, a Yakan in the Philippines when he wants to enter a house correctly.

1.2.3 Revised Premise 3: Turning away from language as the only instrument to code knowledge. Know-ledge is also expressed by means of actions or emotions. Habitual actions in particular can be very ‘eloquent’ in the sense of tacit knowledge. In 1977, the computer specialist Schank and the sociopsychologist Abelson introduced the significant term ‘script’ to describe stereotyped sequences of actions in certain situations. Thus, although language remains one of the focal points, it is treated differently; no longer as a lexicon, but in everyday use as discourse from which inferences must be drawn as to the intended message (Hutchins 1980). Beyond this, the (controversial) idea is that the structure of knowledge (as stored in the mind as representation) is not necessarily language-like: ‘Knowledge organized for efficiency in day-to-day practice is not only nonlinguistic, but also not language-like in that it does not take a sentential logical form’ (Bloch 1991, pp. 189–190). In addition, the question arises whether language should not be ignored more frequently because certain kinds of knowledge cannot be externalized linguistically, or only with great difficulty (Wassmann 1993) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

If the individual acting in his or her daily life now arouses interest, this is a consequence of a paradigmatic change: cognitive anthropology now con-siders itself more clearly as part of the cognitive sciences, which, inter alia, leads to the word ‘cognition’ being better understood. Cognition is no longer an expression of a culture as a whole and abstracted from linguistic material, but understood as the mental activity of individuals who actively apply knowledge in different contexts, in that they think, generalize, draw inferences, perceive, recognize and categorize; analyze, combine, assess possibilities, solve problems and make decisions; classify, differentiate and choose; remember and master new situations. These activities are performed individually or between individuals but, nevertheless, take place somehow within the broad framework of the ‘Culture.’

2. The Representation Of Knowledge

The most important models to represent knowledge in cognitive anthropology are briefly described below.

2.1 Taxonomy

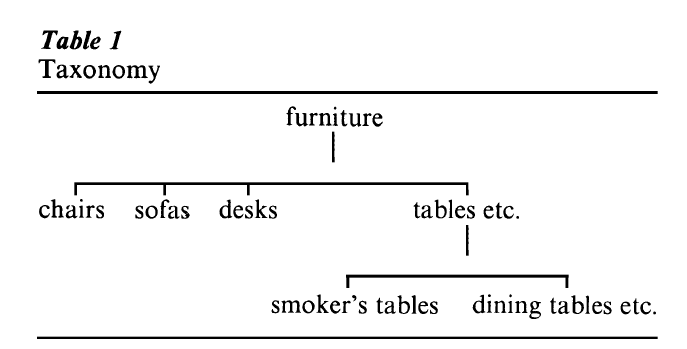

The inner order of a semantic field (e.g., ‘kinship,’ ‘colors’) depends on a small number of ordering principles which structure the lexical components (lexemes) of the field (e.g., ‘mother,’ ‘red’). The ordering principles are inclusion, exclusion (contrast), and intersection. A taxonomy is the description of a semantic field; it lists the categories (lexemes) and shows how they are connected with each other, i.e., according to the principles of inclusion and exclusion in hierarchic order. Categories at the same level exclude each other (exclusion) while categories at the lower level are included in the categories at the higher level (inclusion). The grouping in Table 1 shows that ‘dining tables’ are different from ‘smokers’ tables’ but that both are a kind of table. And also that chairs are distinguished from tables. It does not say what are the distinguishing characteristics.

2.2 Paradigm

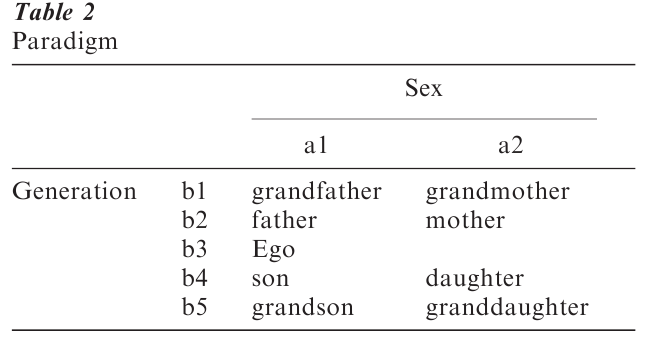

If a semantic field is structured according to the principle of intersection, it is a paradigm. Hierarchy, inclusion, and exclusion are missing; instead the distinctive features (or criterial attributes) are stated which distinguish the different categories. In order to construct such a model, a componential analysis is made (Tyler 1969). A complete lexicon of a semantic field, e.g., ‘blood relationship’ is established and then those characteristics (components) are looked for according to which of the lexemes differ, e.g., ‘male’ and ‘female’ in the dimension ‘sex,’ as well as the distance from Ego in the dimension ‘generation.’ Every single lexeme is now defined by a bundle of components. In the graphic representation in Table 2 these components intersect at the defined lexeme.

Taxonomy and paradigm are the classic models of ethnoscience. They are strongly idealized, consistently emic and only to a small degree ‘cognitive.’ They are understood as the ‘mind’ of a whole culture and (as we know today) they are not really instruments of thinking.

2.3 Prototype

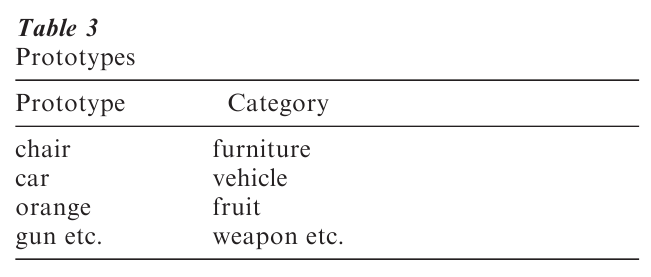

Within a category of objects, that object is a prototype (for the whole category) which is thought to be the best example or the clearest case. Thus, for example, in the category ‘furniture’ the ‘chair’ is a better example than, for instance, ‘radio.’ Of course one could define ‘furniture’ as a category of objects having certain semantic characteristics or attributes in common (and whatever does not have these characteristics does not belong). However, this (checklist) definition does not allow any grading such as ‘chair’ being a better example, more of a prototype of ‘furniture’ than, for instance, ‘radio’ (although both belong to ‘furniture’). It may happen that there are no criterial attributes common to all parts (i.e., no semantic field, no class according to ethnoscience), but only a large number of characteristics which may ‘match’ some but by no means all. As a consequence, they have only a ‘family resemblance’-structure (a term Rosch adopted from Wittgenstein (Rosch and Merris 1975)). Following Levi-Strauss, prototypes are particularly good to think (Table 3).

2.4 Script, Schema And Cultural Model

The information theory approach forces the anthropologist to be explicit. Exactly that has to be made explicit which normally remains implicit. This additional information is called ‘script.’ It is the tacit knowledge enabling us to also understand incomplete descriptions and suggestions: we automatically add what is missing by an inference process. Every situation requires specific knowledge and accordingly there are scripts for ‘eating in a restaurant,’ ‘playing football,’ ‘attending a birthday party.’ But not only our actions are based on scripts, but our language as well, as exemplified briefly in the following; a story told with all the details would be tedious.

I am in New York and somebody asks me the way to Coney Island; I tell him to take the ‘N’-train to the terminus. This instruction only makes sense ‘if this improperly specified algorithm can be filled out with a great deal of knowledge about how to walk, pay for the subway, get in the train and so on’ (Schank and Abelson 1977, p. 20).

If the typical characteristics of a situation are grasped, hence the stereotypical, the standard-like is stressed but raised to a higher level of abstraction; we can talk about schemata and cultural models (which partly replace the older term of the folk model). All the knowledge we acquire, remember, and communicate about this world is neither a simple reflection of this world nor does it consist of a series of categories (as ethnoscience assumed), but it is organized into different situation-relevant, prototypical, simplified sequences of events. We basically think in simplified worlds: ‘… cultural models are composed of prototypical event sequences set in simplified worlds’ (Quinn and Holland 1987, p. 32). What is more, these models are probabilistic and partial; they are actual frames we can use to react to new situations as well. They are world-proposing yet cannot be directly observed, since they are not presented but merely represented by the behavior of the people. They are models of the mind and in the mind. The organizing principle behind these models seems to be metonymy, a part of the whole, the prototypical, conspicuous part is passed off as the whole, i.e., a whole is represented by one of its parts (cf. the frame theory of Minsky, and story grammar by Rumelhart).

2.5 Mental Images

Knowledge may also be represented by inner images. The image schema consists of schematized, simplified images. These images are able to make comprehensible and imaginable physical objects or logical relation-ships difficult to conceptualize. The organizing principle behind them appears to be the metaphor; through analogy, information from the physical world is introduced into the nonphysical world, for example, rage can be imagined as a hot liquid in a container, evaporation as rising molecules springing out of the water like popcorn, electricity as a crowd of people (in front of the gate of a stadium at a sports event).

3. How Deep?

The structure of the representations of knowledge as presented here under Sects. 2.3, 2.4, and 2.5 allows us to answer three questions central to cognitive anthropology (Quinn and Holland 1987, pp. 3–4).

(a) It is able to explain the apparent systematicity of cultural contents (knowledge) by pointing to a number of general-purpose models which can repeatedly be integrated into other concrete models which are special-purpose orientated.

(b) Mastering the enormous amount of knowledge every one of us has is possible because we only store what is prototypical, reduced, but are able to actualize it on demand (in concrete situations), i.e., supplement it with details (instantiation).

(c) It is possible to interpret new experiences because these models not only represent knowledge but also allow us to draw conclusions from them to new situations.

When answering these three questions, modern cognitive anthropology faces three more general problem areas.

3.1 Knowledge And Knowing

Giddens writes ‘The vast bulk of the ‘‘stocks of knowledge’’ … incorporated in encounters is not directly accessible to the consciousness of the actors. Most of such knowledge if practical in character, it is inherent in the capability to ‘go on’ within the routines of social life’ (Giddens 1984, p. 4). Imagine having to describe to somebody how to ride a bicycle; doing so, one has to question the traditional conception of knowledge. It seems to be advantageous to distinguish between knowledge (what is known, as an abstract pool of information, declarative and verbalized) and knowing (how to do something in practice, implicit and hidden, primarily accessed through performance)—the focus being on the latter. We may even reorient our analysis and reverse the process—by starting with knowing and seeing how knowledge is constituted from it (Borofsky 1994).

3.2 Language And Cognition

Does language shape our thinking? This question seems to be receiving attention once more (Gumperz and Levinson 1996). Thus spatial orientation and communicating it certainly belongs to the cognitive and linguistic basic equipment of all people and societies. However, there are different linguistic systems of orientation, and, for us, very basic spatial categories such as ‘left,’ ‘right,’ ‘in front’ or ‘behind’ cannot be taken for granted. Many languages do not know these terms and instead use a geocentric system based, for example, on the cardinal points and use this not only in navigation but also in everyday life (the glass is not placed to the left of the plate but to the east, for instance). However, these differences of a linguistic and cultural kind ( probably) also influence the (cognitive) perception of spatial relationships as well as their storage in memory (Wassmann and Dasen 1998). Here cognitive anthropology contradicts the prevailing school of thought of cognitive linguistics in which the worldwide diversity of languages is only seen as a cultural phenomenon and hence one of surface.

3.3 Universals?

Cognitive processes such as categorizing, classification, memorizing, and perception are the foundations of the contents of knowledge and structure these. In principle they are thought to be universal but can be applied in different ways.

‘We found evidence of differences across cultural groups, differences in habitual strategies for classifying and for solving problems, differences in cognitive style, and differences in rates of progression through developmental stages … These differences, however, are in performance rather than in competence. They are differences in the way basic cognitive processes are applied to particular contexts, rather than in the presence or absence of the processes. Despite these differences, then, there is an underlying universality of cognitive processes’ (Segall et al. 1990, p. 184).

It seems, however, that the deep structure might be influenced by culture in a more lasting way than has been assumed. In the cognitive sciences, the fact that a major part of the mental representations and processes studied might be of a cultural nature receives little attention. Frequently universality is simply postulated without taking into consideration the possibility of a cultural cogeneration. To sensitize cognitive scientists to the ambitious question of the range of cultural variability is a task for which no discipline is better suited than anthropology. A promising field of work for both disciplines could be the PDP-models (Parallel Distributed Processing), also called ‘connectionistic models’ or neuronal networks, which Rumelhart and McClelland (1986) developed as computer models. These are able to construct models of the functioning of schemata: not as loading in a set of instructions, but as gradually building up associative links among repeated or salient aspects of experience. This vague-ness and dependency on empirical knowledge from our everyday life, hence of cultural phenomena, make these models attractive to anthropologists as well (Shore 1996, Strauss and Quinn 1997).

Bibliography:

- Bloch M 1991 Language, anthropology and cognitive science. Man 26: 183–98

- Borofsky R 1994 On the knowledge and knowing of cultural activities. In: Borofsky R (ed.) Assessing Cultural Anthropology. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 331–46

- Giddens A 1984 The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Goodenough W 1957 Cultural anthropology and linguistics. In: Garvin P L (ed.) Reports of the Seventh Annual Round Table Meeting on Linguistics and Language Study. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, pp. 167–73

- Gumperz J, Levinson S C (eds.) 1996 Rethinking Linguistic Relativity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Hutchins E 1980 Culture and Inference. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Keesing R M 1972 Paradigms lost: The new ethnography and the new linguistics. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 28: 299–332

- Keesing R M 1987 Models, ‘folk’ and ‘cultural’: Paradigms regained? In: Holland D, Quinn N (eds.) Cultural Models in Language and Thought. Cambridge University Press, Cam-bridge, UK, pp. 368–93

- Quinn N, Holland D 1987 Culture and cognition. In: Holland D, Quinn N (eds.) Cultural Models in Language and Thought. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Rosch E, Merris C 1975 Family resemblances: Studies in internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology 7: 573–605

- Rumelhart D E, McClelland J L (eds.) 1986 Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Schank R C, Abelson R P 1977 Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding: An Enquiry into Human Knowledge Structures. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Segall M H, Dasen P, Berry J, Poortinga Y 1990 Human Behavior in Global Perspective: An Introduction to Cross-cultural Psychology. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

- Shore B 1996 Culture in Mind: Cognition, Culture, and the Problem of Meaning. Oxford University Press, New York

- Strauss C, Quinn N 1997 A Cognitive Theory of Cultural Meaning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Tyler S (ed.) 1969 Cognitive Anthropology: Readings. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York

- Wassmann J 1993 Das Ideal des Leicht Gebeugten Menschen. Eine Ethno-Kognitive Analyse der Yupno on Papua Neuguinea. Reimer Verlag, Berlin

- Wassmann J, Dasen P R 1998 Balinese spatial orientation. Some empirical evidence of moderate linguistic relativity. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 44: 689–711