Sample Anthropology of Performance Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Anthropology uses the concept of performance to refer to distinctive events or aspects of behavior, contributing to the understanding of human behavior in traditional, nontraditional, and avant-garde contexts. The current applications range from the most extraordinary and stylized forms of human behavior to the fundamental routines of everyday life, and address different areas of specialized professionalism and expertise, in ritual, commercial, economic, medical, dramatic, and sportive spheres. Initially driven by a theoretical concern with social function and meaning, contemporary research uses the performance concept to address issues of identity and the relationship between performance, self, researcher, and social space.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Development Of The Concept

Performance as an anthropological concept developed after the 1950s. Previously, anthropologists subsumed performance into the analysis of ritual. In British social anthropology, which had built its reputation as a science of total functioning systems and structures centred on kinship networks, specialized forms of human behavior occurring within modern or commercial venues, such as acting or dancing, were considered marginal subjects. By the mid-1960s, however, broader humanist concepts of culture, more powerful in anthropology elsewhere in Europe and in the USA, allowed the concept of performance to enter more centrally into anthropological analyses.

The American sociologist Erving Goffman (1956, p. 23) developed a model in which social interaction was explicable as acts and performances: ‘The world, in truth, is a wedding,’ and performance is ‘all of the activity of a given participant on a given occasion which serves to influence in any way any of the other participants’ (Goffman 1956, p. 8). Goffman unified the analysis of roles and situations using theatrical metaphors such as front and back stage to explain different aspects of behavioral presentation and ‘multiple versions of reality.’ This model was intended as a fifth analytical perspective to complement existing technical, political, structural, and cultural ones. This dramaturgical and transactional vision of social interaction remains influential.

Milton Singer, Dell Hymes, Clifford Geertz, and Victor Turner have also shaped the ways in which anthropologists use performance notions metaphorically to explain social action as a complex system of symbolic and meaningful behavior which produces an ordered understanding of the world (Geertz 1973). Performance in these terms is not limited to representation, but is an active and creative precondition for social life.

Victor Turner’s work has been particularly influential on current uses of performance. He moved from a functionalist study of ritual to cultural performance models and finally to theatrical performance itself, though performance was never separated completely from ritual, a ‘transformative performance revealing major classifications, categories, and contradictions of cultural process’ (Ronald L. Grimes, cited in Turner 1986, p. 75). Turner developed three linked explanatory concepts. ‘Ritual process’ consists of separation, transition or liminality, and reintegration. Anti-structure or ‘communitas’ contrasts with the structure of everyday life and describes the creative and expressive behavior associated with a generalized notion of liminality beyond the simple process of a specific ritual event. ‘Social dramas’ extend the ritual process into other kinds of social scenario. This framework merged the borders between initiation rituals, social events such as carnivals, and particular theatrical performances, as what Wilhelm Dilthey called ‘lived experience’ (Turner 1986, pp. 84–90).

Turner was part of Max Gluckman’s ‘Manchester School’ of anthropology, but he has been more influential in the USA than others from this school. Other scholars of this background produced actor- centered transactional and conflict models using performance perspectives on more political topics, often drawing on Marxist theory. In his study of London’s Notting Hill Carnival, Abner Cohen (1993) reaffirms his interest in performance as part of a wider analysis of the relationship between cultural forms and political formations: performance as a part of political symbolism is interesting because of the contradictions between the two dimensions of social interaction: the unintentional and moral nature of cultural action, and the amoral self-interest of political action. Cohen’s work has influenced the analysis of performance as a political tool in postcolonial societies where processes of retribalization and issues of ethnic identity have been so dominant (Parkin et al. 1996).

The study of cultural performances has been inflected towards ritual and personal transformation, or towards contradictions and political conflict, although the proponents of each ‘side’ would all claim to be attempting to bridge such dualisms. None the less, labels such as ‘humanist’ and ‘Marxist’ continue to limit any such transcendence, despite the best efforts of those who have insisted on the multiplicity of social life (Tambiah 1985).

Other salient influences came from sociolinguistics. Theories which characterized communication as per-formative, and not just informative, were inspired by Jakobson’s ‘poetic function’—‘the way in which a communication is carried out’ (Bauman 1986, p. 3) —and Austin and Searle’s speech act theory. For instance, Richard Bauman (1986, p. 112) has analyzed American folk narratives using a framework of story, performance, and event. This specialized use of performance has been very influential in establishing the performative dimensions of different kinds of communication, particularly in the study of competence and play. Anthropologists have also developed communicative approaches to the performance of metaphor in various social contexts (Fernandez 1986). Such work on verbal performance has influenced general theories of performance in human behavior, but although it has moved away from a text-based model, it has produced somewhat disembodied accounts of performance, with little reference to the nonverbal gestural dimension of human communication and expression.

2. Methodological Innovations

These influences have legitimized performance as a topic within anthropology, and Turner’s last writings on performances as liminoid phenomena have promoted an interest in nontraditional performance, overlapping with performance studies and cultural studies. There has also been a belated recognition of the importance of embodied behavior and bodily techniques.

Increasing attention is being paid to different performance skills and genres, not simply as objects of study but also methodologically. Anthropology has always been a discipline which attracts people with an experience of life outside academe, and the 1980s saw the emergence of performer-anthropologists, scholars who had previously worked on the stage professionally as dancers and actors. Anthropologists who have not been professional actors or dancers may choose to include training in performance as part of their research, using their bodies to explore familiar or unfamiliar techniques self-consciously by learning alongside aspiring professionals and experts. This recognition of the importance of embodiment is part of a broader trend to understand human knowledge as a reflexive situated practice, validated not by observation, but by experience (Hastrup 1995, p. 83).

The traditional anthropological interest in ritual which Turner extended to theater also resulted in an intellectual collaboration with Richard Schechner, a theatre director and academic. After Turner’s death in 1983 Schechner kept the effort alive, both practically and theoretically. The continuum between performance with ritual efficacy and theatrical performance rests on the theory that performance is ‘restored behavior’, strips of behavior with ‘a life of their own’, which can be rearranged or reconstructed independently of the various causal systems which brought them into existence (Schechner 1985, p. 35).

Schechner has played an important role in forging a meeting between the performers, anthropologists and other researchers of intercultural performance. This wide and fuzzy interdisciplinary field has become well established in the USA and is gaining momentum in the UK and Europe. The International School of Theatre Anthropology founded by Eugenio Barba and Nicola Savarese has involved performers from Japan, India, Indonesia, and Brazil. Theater anthropology is not the study of the performative phenomena by anthropologists, but rather the study of the preexpressive behavior of the human being in an organized performance situation (Barba 1995, p. 10).

In 1990, the anthropologist Kirsten Hastrup’s life story was ‘restored’ (to use Schechner’s term) as a drama, Talabot by Barba’s Odin Teatret (Hastrup 1995, pp. 123–45). New and established anthropologists are also turning to different performance arenas, including cinema, television, and the internet, to explore further permutations of sociality which would have been unimaginable a hundred years ago (HughesFreeland and Crain 1998).

Anthropological analyses and uses of performance are not limited to the technicalities of theater and acting. Johannes Fabian (1990) has argued that performance must deal with the political, and has worked with a theater troupe in Zaire to explore local concepts of power through drama and television. The sociolinguistic approach to performance has also been applied to analyze powerful speaking in Sumba, East Indonesia, which has been repressed by the State and transformed into textbook culture (Kuipers 1990). The social processes of power are also the center of Ward Keeler’s (1987) study of shadow puppet theatre in Java. Studies such as these are found among the ethnography of every region, and often remain independent of the meeting between anthropology and performance studies.

The relationship between ritual and performance is generating approaches to the study of healing in a number of interesting ways. Such studies use transactional and conflict models but also consider the power of the aesthetic and expressive dimensions of performance in the face of political repression or disenfranchisement. For example, the healing power of comedy in an exorcism in Sri Lanka restores the sick person to a sense of social integration, in line with G. H. Mead’s theory (Kapferer 1991). Michael Taussig (1993) invokes Marx and the Frankfurt School to explore mimetic behavior which lies at the heart of shamanic healing and social imagery, simultaneously representing and falsifying the world, and demonstrates how irrationality is being performed at the heart of the everyday. ‘Mimetic excess’ creates ‘reflexive awareness’, which makes connections between history, make-believe, and otherness.

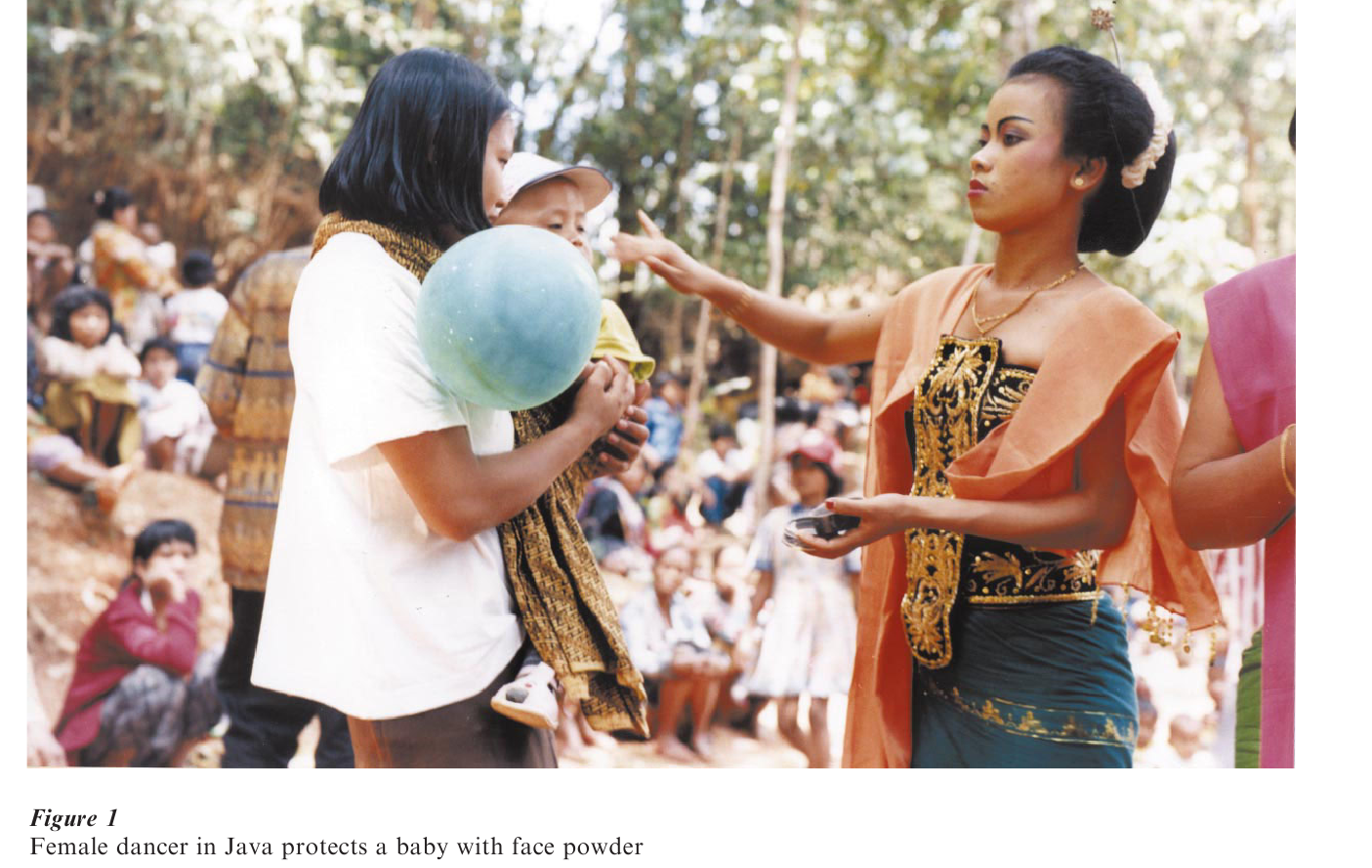

Bureaucratic resistance to the irrational is also at issue, as in the case of professional female performers in Indonesia, who had the power to mediate between the village spirit made manifest by the village elder and the community, and brought healing and protective energies to local communities (see Fig. 1). These performers are being made extinct by the processes of state education and professionalization, which tend to deny female power (Hughes-Freeland 1997).

Performance here differs from the rational calculation of Goffman’s social agents, and introduces complexity into the debate about the extent of individual human choice and intentionality. Such explorations are a reminder of the continuing usefulness of studying ritual performance to understand how humans express their possession and dispossession, and the permeability of the boundary between ritual performance and artistic performance.

More radically, anthropologists have applied healing processes from other cultures to help the sick at heart in their own societies by means of ‘a theatre model of dramatherapy’ (Jennings 1995, p. xxvii). While Aristotle’s concept of catharsis may seem universal, different theatres produce forms of what Sue Jennings (1995, p. 185) calls ‘abandonment’, which vary greatly in their effects and forms of control. Ultimately it is this variation which must concern the anthropologist.

3. Central Issues

During the 1970s, the anthropological project was framed by questions about function and meaning, but these have been superseded by concerns with identity and experience. Performance is productive of individuals, with gendered, ethnic, or other specified markers of social identity. It has also been argued that it produces the experience of society as a continuum (Parkin et al. 1996, p. xvii). By using the performance concept in a heuristic manner, anthropologists are able to develop insights into the acquisition of competence, as general socialization or as training to acquire particular skills, and to further their understanding of social interactions and formations.

The central problem facing anthropologists working on, and by means of, performance remains the question of boundaries. The topic continues to stimulate argument: is performance a discrete category, or is it an aspect of everyday behavior? How does performance help us to understand reality? (HughesFreeland 1998, pp. 10–15).

An interesting debate about performance is the extent to which human action is scripted or emergent. Is performance best understood as mimesis and imitation, or as poesis, creative, emergent, and transformative? Anthropological self-critiques are often formulated along the lines of performance models vs. textual models, and argue for process models vs. structural ones. One party stresses the determinacy of form, the other gives primacy to emergence, praxis, experience. These arguments situate performance centrally within current polemics about anthropological knowledge, and whether it should represent itself as operating within a system of models and rules, or performatively and dialectically. Anthropologists now approach performance as being risky and interactive, rather than determined and predictable, using active and participatory models of spectatorship, not passive ones, on a continuum of general varieties of human interaction.

Some commentators have questioned the general applicability of the Western view of performance as illusion, as theatrical, as unfactual, since such a view does not necessarily accord with the ways in which activities categorized as performances by anthropologists may be understood by members of the societies in which they occur (Schieffelin 1998). Others by contrast suggest that the exposure of the acting body makes deception impossible (Hastrup 1995, p. 91). By questioning critically the presuppositions supporting categorical oppositions implied in performance, such as pretense vs. authenticity, and by going against the grain of their own cultural presuppositions, anthropologists are able to construct descriptions of alternative ways of seeing and being in the world, and to celebrate the diversity of human cultural experience despite its shared biophysical nature. Anthropologists thus differ in their treatment of performance from those working in other disciplines.

4. Future Directions

As human interaction intensifies across time and space, anthropological approaches to performance recognize the complexity of contemporary life and the superficiality of dichotomizing the ‘everyday’ vs. ‘ritual’ realities. Information and media technologies facilitate virtual realities, and complicate the different ways in which performance may be transmitted and received, beyond the defined space–time continua of theatre, ritual arena, or event. Technological innovations in this way make it necessary for the analysis of performance to spill over again from specialized behavioral contexts into emergent everyday lives ((Hughes-Freeland and Crain 1998).

Visual technologies can bring all kinds of performance to us in nonverbal ways, unmediated by words, using images instead. Although these images are not pure imitations of the performances as they occur, it could be argued that the researcher is freer to respond directly to the performance than when reading about it. For example, Jean Rouch’s film of the Hauka possession cult in Ghana in 1953, Les Maıtres Fous (The Mad Masters) presents images which language might fail to represent as convincingly real. Experimental ethnographic explorations of the relationship between embodied performance and text suggest innovative and exciting approaches to issues of analysis and representation in anthropology.

The potential fields for the development of anthropological approaches to performance are numerous. The study of linguistic performance has already been employed in communication analyses in the field of artificial intelligence, a development which might extend to understandings of embodied performance. The anthropology of performance, perhaps the most ostensibly humanist of the new sub-areas of anthropology, could move increasingly into the field of medical and information technologies, theoretical and practically. In the more immediate future, anthropologists work to develop a less culturally entrenched view of human performance activities, and engage in intracultural or cross-cultural performances to promote wider understanding about the different ways of acting human within the constraints of the group, and the challenges performance presents to those constraints.

Bibliography:

- Barba E 1995 The Paper Canoe. Routledge, London

- Bauman R 1986 Story, Performance, and Event. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Cohen A 1993 Masquerade Politics. Berg, Oxford, UK

- Fabian J 1990 Power and Performance. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI

- Fernandez J W 1986 Persuasions and Performances: The Play of Tropes in Culture. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN

- Geertz C 1973 The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic Books, New York

- Goffman E 1956 The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre, Monograph No. 2, Edinburgh, UK

- Hastrup K 1995 A Passage to Anthropology: Between Experience and Theory. Routledge, London

- Hughes-Freeland F 1997 Art and politics: from Javanese court dance to Indonesian art. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 3(3): 473–95

- Hughes-Freeland F (ed.) 1998 Ritual, Performance, Media. Routledge, London

- Hughes-Freeland F, Crain M M (eds) 1998 Recasting Ritual: Performance, Media, Identity. Routledge, London

- Jennings S 1995 Theatre, Ritual and Transformation: The Senoi Temiars. Routledge, London

- Kapferer B 1991 A Celebration of Demons, 2nd edn. Berg Smithsonian Institution Press, Oxford, UK Princeton, NJ

- Keeler W 1987 Javanese Shadow Plays, Javanese Selves. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Kuipers J C 1990 Power in Performance. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Parkin D, Caplan L, Fisher H (eds.) 1996 The Politics of Cultural Performance. Berghahn Books, Oxford, UK

- Schechner R 1985 Between Theater and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Schieffelin E L 1998 Problematizing performance. In: Hughes Freeland F (ed.) Ritual, Performance, Media. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 194–207

- Tambiah S J [1981] 1985 Culture, Thought and Social Action: An Anthropological Perspective. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Taussig M 1993 Mimesis and Alterity. Routledge, New York

- Turner V W 1986 [1987] The Anthropology of Performance. Performing Arts Journal, New York