View sample interpersonal theory of personality research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Interpersonal Foundations for an Integrative Theory of Personality

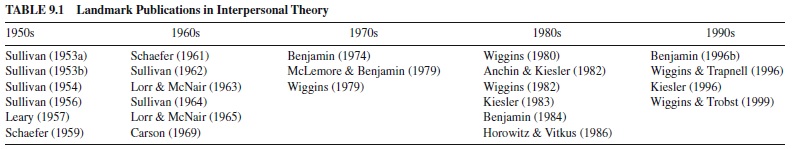

The origins of the interpersonal theory of personality we discuss in this research paper are found in Sullivan’s (1953a, 1953b, 1954, 1956, 1962, 1964) interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Extensions, elaborations, and modifications have consistently appeared over the last 50 years, with landmark works appearing in each successive decade (see Table 9.1). Given this clear line of theoretical development, it might seem puzzling that in a discussion of the scope of interpersonal theory held at a recent meeting of the Society for Interpersonal Theory and Research (SITAR), it was pointed out that psychology’s expanding focus on interpersonal functioning has rendered study of interpersonal processes so fundamental that interpersonal theory risks an identity crisis (Gurtman, personal communication, June 20, 2000). In our opinion, both promising and perplexing aspects of this identity crisis are respectively reflected in two growing bodies of literature. The former body recognizes the integrative and synthetic potential of interpersonal theory to complement and enhance many other theoretical approaches to the study of personality (e.g., Benjamin, 1996c; Kiesler, 1992), whereas the latter body focuses on interpersonal functioning without any recognition of interpersonal theory.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Explicit efforts have been made toward integration of interpersonal theory and cognitive theory (e.g., Benjamin, 1986; Benjamin & Friedrich, 1991; Carson, 1969, 1982; Safran, 1990a, 1990b; Tunis, Fridhandler, & Horowitz, 1990), attachment theory (e.g., Bartholomew & L. Horowitz, 1991; Benjamin, 1993; Birtchnell, 1997; Florsheim, Henry, & Benjamin, 1996; Pincus, Dickinson, Schut, Castonguay, & Bedics, 1999; Stuart & Noyes, 1999), contemporary psychodynamic theory (e.g., Benjamin, 1995; Benjamin & Friedrich, 1991; Heck & Pincus, 2001; Lionells, Fiscalini, Mann, & Stern, 1995; Pincus, 1997; Roemer, 1986), and evolutionary theory (e.g., Hoyenga, Hoyenga, Walters, & Schmidt, 1998; Zuroff, Moskowitz, & Cote, 1999). Although it might be argued that such efforts could lead to identity diffusion of interpersonal theory, we believe this points to the fundamental integrative potential of an interpersonal theory of personality. In contrast, efforts at integrating interpersonal theory with social psychological theories of human interaction and social cognition appear to be lagging despite the initial works of Carson (1969) and Wiggins (1980). We note continued expansion of a significant social psychological literature on interpersonal behavior, such as self-verification and self-confirmation theories (e.g., Hardin & Higgins, 1996; Swann & Read, 1981) and interpersonal expectancies (e.g., Neuberg, 1996), that does not incorporate interpersonal theory as reviewed here. Remarkably, recent reviews of interpersonal functioning (Reis, Collins, & Berscheid, 2000; Snyder & Stukas, 1999) did not cite any of the literature reviewed for this research paper on interpersonal theory, nor do interpersonal theorists regularly recognize the social psychological literature on interpersonal interaction in their work (cf. Kiesler, 1996).

Thus, the current state of affairs compels interpersonal theorists to take the next step in defining the interpersonal foundations for an integrative theory of personality. The initial integrative efforts provide a platform to refine the scope of interpersonal theory, and the areas in which integration is lacking indicate that further development is necessary. The goal of this research paper is to begin to forge a new identity for interpersonal theory that recognizes both its unique aspects and integrative potential; in this research paper, we also suggest important areas in need of further theoretical development and empirical research.

The Interpersonal Situation

I had come to feel over the years that there was an acute need for a discipline that was determined to study not the individual organism or the social heritage, but the interpersonal situations through which persons manifest mental health or mental disorder. (Sullivan, 1953b, p. 18)

Personality is the relatively enduring pattern of recurrent interpersonal situations which characterize a human life. (Sullivan, 1953b, pp. 110–111)

These statements are remarkably prescient, as much of psychology in the new millenium seems devoted in one way or another to studying interpersonal aspects of human existence. To best understand how this focus has become so fundamental to the psychology of personality (and beyond), we must clarify what is meant by an interpersonal situation. Perhaps the most basic implication of the term is that the expression of personality (and hence the investigation of its nature) focuses on phenomena involving more than one person—that is to say, some form of relating is occuring (Benjamin, 1984; Kiesler, 1996; Mullahy, 1952). Sullivan (1953a, 1953b) suggested that individuals express “integrating tendencies” that bring them together in the mutual pursuit of both satisfactions (generally a large class of biologically grounded needs) and security (i.e., self-esteem and anxiety-free functioning).

These integrating tendencies develop into increasingly complex patterns or dynamisms of interpersonal experience. From infancy onward through six developmental epochs these dynamisms are encoded in memory via age-appropriate learning. According to Sullivan, interpersonal learning of social behaviors and self-concept is based on an anxiety gradient associated with interpersonal situations. All interpersonal situations range from rewarding (highly secure) through various degrees of anxiety and ending in a class of situations associated with such severe anxiety that they are dissociated from experience. Individual variation in learning occurs when maturational limits affect the developing a person’s understanding of cause-and-effect logic and consensual symbols such as language (i.e., Sullivan’s prototaxic, parataxic, and syntaxic modes of experience), understanding of qualities of significant others (including their “reflected appraisals” of the developing person), as well as their understanding of the ultimate outcomes of interpersonal situations characterizing a human life. Thus, Sullivan’s concept of the interpersonal situation can be summarized as the experience of a pattern of relating self with other associated with varying levels of anxiety (or security) in which learning takes place that influences the development of self-concept and social behavior. This is a very fundamental human experience for psychology to investigate, and it is a significant aspect of the efforts to integrate interpersonal theory with cognitive, attachment, psychodynamic, and evolutionary theories previously noted.

Sullivan (1954) described three potential outcomes of interpersonal situations. Interpersonal situations are resolved when integrated by mutual complementary needs and reciprocal patterns of activity, leading to “felt security” and probable recurrence. A well-known example is the resolution of an infant’s distress by provision of tender care by parents. The infant’s tension of needs evokes complementary parental needs to provide care (Sullivan, 1953b). Interpersonal situations are continued when needs and patterns of activity are not initially complementary, such that tensions persist and covert processing of possible alternative steps toward resolution emerge, leading to possible negotiation of the relationship (Kiesler, 1996). Finally, interpersonal situations are frustrating when needs and actions are not complementary and no resolution can be found, leading to an increase in anxiety and likely disintegration of the situation.

For Sullivan, the interpersonal situation underlies genesis, development, mutability, and maintenance of personality. The continuous patterning and repatterning of interpersonal experience in relation to the vicissitudes of satisfactions and security in interpersonal situations gives rise to lasting conceptions of self and other (Sullivan’s “personifications”) as well as to enduring patterns of interpersonal relating. To us, the interpersonal situation is at the core of an interpersonal theory of personality. The power of interpersonal experiences to create, refine, and change personality as Sullivan conceived is the foundation of an interpersonal theory of personality that has been elaborated in the last half century by a wide range of theoretical, empirical, and clinical efforts.

A comprehensive theory of personality includes contemporaneous analysis emphasizing present description and developmental analysis emphasizing historical origins as well as the continuing significance of past experience on current functioning (Millon, 1996). Consistent with these approaches, the fundamental aspects of an interpersonal theory of personality should include (a) a delineation of what is meant by interpersonal, (b) the systematic description of interpersonal behavior, (c) the systematic description of reciprocal interpersonal patterns, (d) articulation of processes and structures that account for enduring patterns of relating, and (e) motivational and developmental principles. In our opinion, interpersonal theorists have reached greater consensus on contemporaneous description than on developmental concepts. This consensus may be due in part to ambiguity in the meaning of the term interpersonal.

The Interpersonal and the Intrapsychic

Where are interpersonal situations to be found? Millon’s (1996) distinction between contemporaneous and developmental analysis alludes to the dichotomy of the interpersonal and the intrapsychic. Specifically, current description evokes a view of the reciprocal behavior patterns of two persons engaged in resolving, negotiating, or disintegrating their present interpersonal situation. In this sense, we might focus on what can be observed to transpire between them. In contrast, developmental analysis implies that there is something relatively stable that a person brings to each new interpersonal situation. Such enduring influences might be considered to reside within the person—that is, they are intrapsychic. The dichotomous conception of the interpersonal and the intrapsychic as two sets of phenomena—one residing between people and one residing within a person—may have at times led interpersonal theorists to focus more attention on contemporaneous analysis with perhaps greater hesitancy to elaborate on developmental influences. In our opinion, however, we must include developmental concepts if we are to be comprehensive, and this in turn requires examination of intrapsychic structures and processes. As it turns out, Sullivan would not be opposed to such efforts.

Greenberg and Mitchell (1983) point out that Sullivan’s interpersonal theory of psychiatry was largely a response to Freud’s strong emphasis on drive-based intrapsychic aspects of personality. Because of Sullivan’s opposition to drives as the source of personality structuralization, there is a risk of simplifying interpretation of interpersonal theory as focusing solely on what occurs outside the person, in the world of observable interaction. Mitchell (1988) points out that Sullivan was quite amenable to incorporating the intrapsychic into interpersonal theory because he viewed the most important contents of the mind to be the consequence of lived interpersonal experience. For example, Sullivan (1964) states, “. . . everything that can be found in the human mind has been put there by interpersonal relations, excepting only the capabilities to receive and elaborate the relevant experiences” (p. 302; see also Stern, 1985, 1988).

Mitchell (1988) specifies several concepts associated with the dichotomization of interpersonal and intrapsychic, including perception versus fantasy and actuality versus psychic reality. Sullivan clearly viewed fantasy as fundamental to interpersonal situations. He defined psychiatry as the “study of the phenomena that occur in configurations made up of two or more people, all but one of whom may be more or less completely illusory” (Sullivan, 1964, p. 33). These illusory aspects of the interpersonal situation involve mental structures—that is, personifications of self and others. Sullivan (1953b) was forceful in asserting that personifications are elaborated organizations of past interpersonal experience, stating “. . . I would like to make it forever clear that the relation of the personifications to that which is personified is always complex and sometimes multiple; and that personifications are not adequate descriptions of that which is personified” (p. 167). Sullivan also saw subjective meaning (i.e., psychic reality) as highly important. For example, Mitchell (1988) points out that Sullivan’s conception of parataxic integration involves subjective experience of the interpersonal situation influenced by intrapsychic structure and process. Sullivan (1953a) describes parataxic integrations as occurring “when, beside the interpersonal situation as defined within the awareness of the speaker, there is a concomitant interpersonal situation quite different as to its principle integrating tendencies, of which the speaker is more or less completely unaware” (p. 92). In discussing the data of psychiatry, Sullivan (1964) asserted that “human behavior, including the verbal report of subjective appearances (phenomena), is the actual matter of observation” (p. 34).

Thus, we can assert that interpersonal theory is not strictly an interactional theory emphasizing observable behavior; rather, the term interpersonal is meant to convey a sense of primacy, a set of fundamental phenomena important for personality development, structuralization, function, and pathology. It is not a geographic indicator of locale: It is not meant to generate a dichotomy between what is inside the person and what is outside the person. From a Sullivanian standpoint, the intrapsychic is intrinsically interpersonal, derived from the registration and elaboration of interactions occurring in the interpersonal field (Mitchell, 1988). As we will see, however, descriptions of observable interpersonal behavior and patterns of relating have generated far more consensus among interpersonal theorists than have elaboration of intrapsychic processes and concepts.

Describing Interpersonal Behavior

The emphasis on interpersonal functioning in Sullivan’s work stimulated efforts to develop orderly and lawful conceptual and empirical models describing interpersonal behavior. The goal of such work was to obtain a taxonomy of interpersonal behavior—“to obtain categories of increasing generality that permit description of behaviors according to their natural relationships” (Schaefer, 1961, p. 126; see also Millon, 1991, for a general discussion of taxonomy in classification of personality and psychopathology). In contemporary terms, such systems are referred to as structural models, which can be used to conceptually systematize observation and covariation of variables of interest. If sufficiently integrated with rich theory, such models can even be considered nomological nets (Benjamin, 1996a; Gurtman, 1992).

There have been two distinct but related empirical approaches to the development of structural models describing interpersonal functioning. We refer to these as the individual differences approach and the dyadic approach (Pincus, Gurtman, & Ruiz, 1998). These authors pointed out that although each approach has unique aspects, the approaches converge in that they assert that the best structural model of interpersonal behavior takes the form of a circle or circumplex (Gurtman & Pincus, 2000; Pincus et al., 1998; Wiggins & Trobst, 1997). The geometric properties of circumplex models give rise to unique computational methods for assessment and research (Gurtman, 1994, 1997, 2001; Gurtman & Balakrishnan, 1998; Gurtman & Pincus, in press) that are not reviewed here. In this research paper, circumplex models of interpersonal behavior are used to anchor description of theoretical concepts. The development of circumplex models of interpersonal behavior has significantly influenced contemporary developments in interpersonal theory, and vice versa (Pincus, 1994).

The Individual Differences Approach

The individual differences approach focuses on qualities of the individual, (e.g., personality traits) that are assumed to give rise to behavior that is generally consistent over time and across situations (Wiggins, 1997). From a relational standpoint, this approach involves behavior which is also generally consistent across interpersonal situations, giving rise to the individual’s interpersonal style (e.g., Lorr & Youniss, 1986; Pincus & Gurtman, 1995; Pincus & Wilson, 2001), and in cases of psychopathology, an individual’s interpersonal diagnosis (Kiesler, 1986; Leary, 1957; McLemore & Benjamin, 1979; Wiggins, Phillips, & Trapnell, 1989).

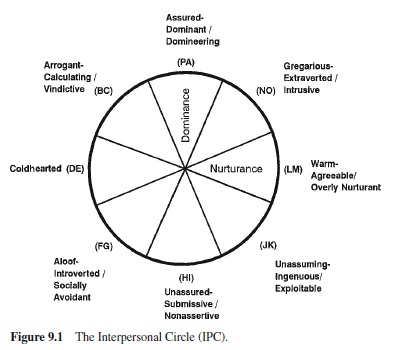

The individual differences approach led to the empirical derivation of a popular structural model of interpersonal traits, problems, and behavioral acts often referred to as the Leary circle (Freedman, Leary, Ossorio, & Coffey, 1951; Leary, 1957) or the Interpersonal Circle (IPC; Kiesler, 1983; Pincus, 1994; Wiggins, 1996). Leary and his associates at the Kaiser Foundation Psychology Research Group observed interactions among group psychotherapy patients and asked, “What is the subject of the activity, e.g., the individual whose behavior is being rated, doing to the object or objects of the activity?” (Freedman et al., 1951, p. 149). This contextfree cataloging of all individuals’ observed interpersonal behavior eventually led to an empirically derived circular structure based on the two underlying dimensions of dominance-submission on the vertical axis and nurturance-coldness on the horizontal axis (see Figure 9.1).

The IPC model is a geometric representation of individual differences in a variety of interpersonal domains, including interpersonal traits (Wiggins, 1979, 1995), interpersonal problems (Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 2000), verbal and nonverbal interpersonal acts (Gifford, 1991; Kiesler, 1985, 1987), and covert interpersonal impacts (Kiesler, Schmidt, & Wagner, 1997; Wagner, Keisler, & Schmidt, 1995). Thus, all qualities of individual differences within these domains can be described as blends of the circle’s two underlying dimensions. Blends of dominance and nurturance can be located along the 360º perimeter of the circle. Interpersonal qualities close to one another on the perimeter are conceptually and statistically similar, qualities at 90º are conceptually and statistically independent, and qualities 180º apart are conceptual and statistical opposites. Although the circular model itself is a continuum without beginning or end (Carson, 1969, 1996; Gurtman & Pincus, 2000), any segmentalization of the IPC perimeter to identify lower-order taxa is potentially useful within the limits of reliable discriminability. The IPC has been segmentalized into sixteenths (Kiesler, 1983), octants (Wiggins, Trapnell, & Phillips, 1988), and quadrants (Carson, 1969).

Although the IPC represents a model of functioning in which the individual is presumed to be in many possible interpersonal situations, the model itself is monadic. The IPC structure does not include specific structural or contextual Bibliography: to the interacting other. Most often, it is used to describe qualities of the individual interacting with a “generalized other” (Mead, 1932; Sullivan, 1953a, 1953b), such as the “hostile-dominant patient” interacting with a generic “psychotherapist” (e.g., Gurtman, 1996; Horowitz, Rosenberg, & Kalehzan, 1992).

The Dyadic Approach

In contrast to the individual differences approach, a second approach assumes that the basic unit of analysis for the study of interpersonal functioning was the dyad. As is the case for the IPC, there is a long history of theoretical and empirical conceptualizations of dyadic interpersonal functioning.At the same time that Leary and his colleagues were investigating individual differences in interpersonal behavior, Schaefer (1959, 1961) began investigating mother-child dyads in an effort to develop a structural model of interpersonal behavior. His methods were similar, but he emphasized the specific dyad as the basic unit of observation: “For maternal behavior, the universe [of content] is the behavior of the mother directed toward an individual child, excluding all other behaviors of the mother” (Schaefer, 1961, p. 126). His work showed a remarkable convergence with Leary (1957)—both investigators found that a two-dimensional circular model best represented interpersonal behavior. As with the IPC, the horizontal dimension was love-hostility. However, the vertical dimension differed, and was labeled autonomy, ranging from autonomygranting to controlling. Given a dyadic focus, Schaefer (1961) also derived a complementary circular model of children’s behavior in reaction to mothers. Although this early model failed to parallel his maternal behavior model, the notion that parent-like interpersonal behaviors and childlike interpersonal behaviors may be distinguished from each other was an important advance that led to the development of a second prominent circular model of interpersonal behavior from a dyadic point of view.

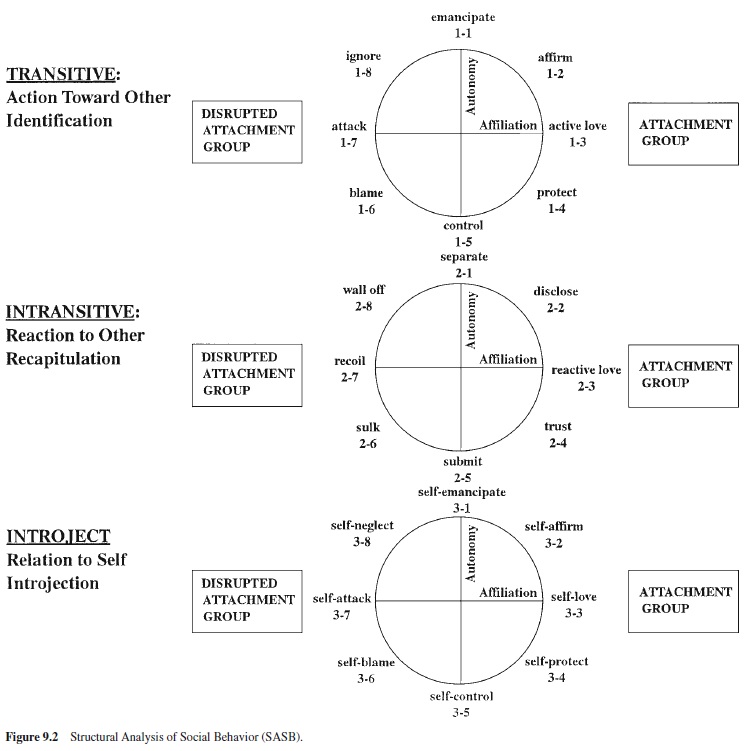

Structural Analysis of Social Behavior (SASB; Benjamin, 1974, 1984, 1996a, 1996b, 2000) is a complex three-plane circumplex that operationally defines interpersonal and intrapsychic interactions (see Figure 9.2). The dimensions underlying SASB include autonomy (i.e., enmeshmentdifferentiation on the vertical axis), affiliation (i.e., love-hate on the horizontal axis), and interpersonal focus (i.e., parentlike transitive actions towards others represented by the top circle, childlike intransitive reactions to others represented by the middle circle, and introjected actions directed toward the self represented by the bottom circle). Benjamin (1996c) described the development of SASB as an effort “to combine the prevailing clinical wisdom about attachment with the descriptive power of the circumplex as Schaefer had envisioned it” (p. 1204). The unique multiplane structure of SASB also incorporates Sullivan’s concept of introjection— that is, the expected impact of interpersonal situations on the self-concept—by proposing a third corresponding circle that reflects how one relates to self.

By separating parent-like and childlike behaviors into two planes, SASB incorporates both the vertical dimension of Schaefer’s model (control vs. emancipate) and that of the IPC (dominate vs. submit). The transitive surface represents the former, whereas the intransitive surface opposes submission with autonomy-taking. Thus, according to circumplex geometry, controlling and autonomy-granting are opposite interpersonal actions, whereas submitting and autonomy-taking are opposite interpersonal reactions (Lorr, 1991). Dominance and submission are placed at comparable locations on different surfaces to reflect the fact that they are complementary positions rather than opposites. Thus, SASB expands interpersonal description by including taxa reflecting friendly and hostile differentiation (e.g., affirming, ignoring) not defined within the IPC structure, as well as describing the introjected relationship with self. Although the vertical dimensions and complexity of SASB set it apart from the IPC, the same geometric assumptions are applicable. Interpersonal behaviors located along the perimeters of the SASB circles (identified as clusters in SASB terminology) represent blends of the basic dimensions with the same geometric relations among clusters on each surface.

To complete the description, we note that attachment concepts have been incorporated into the SASB structure (Benjamin, 1993, 1996a, Florsheim et al., 1996; Henry, 1994). Boxes in Figure 9.2 denote that interpersonal elements on the right side of the circles (affirm-disclose, reciprocal love, protect-trust) represent the attachment group (AG). Interpersonal elements on the left side of the circles (blamesulk, attack-recoil, ignore-wall off) represent the disrupted attachment group (DAG).

Using this expanded taxonomy, SASB describes a dyadic interpersonal unit—that is, a real or internalized relationship—rather than the qualities of a single interactant. For example, psychotherapy research using SASB has focused on the therapist-patient dyad as the unit of investigation (e.g., Henry, Schacht, & Strupp, 1990). Despite these differences, we view the structural models derived from the individual differences and dyadic approaches to be highly convergent in many respects, and they should be viewed as complementary approaches rather than mutually exclusive competitors (e.g., Pincus, 1998; Pincus & Wilson, 2001).

Interpersonal Reciprocity and Transaction

The notion of reciprocity in human relating is reflected in a wide variety of psychological concepts including repetition compulsion (Freud, 1914, 1920), projective identification (Grotstein, 1981), core conflictual relational themes (Luborsky & Crits-Cristoph, 1990), self-fulfilling prophecies (Carson, 1982), vicious circles (Millon, 1996), selfverification seeking (Swann, 1983), and object-relational enactments (Kernberg, 1976), to name a few. If we assume that an interpersonal situation involves two or more people relating to each other in ways that bring about social and selfrelated learning, this implies that something is happening that is more than mere random activity. Reciprocal relational patterns create an interpersonal field (Wiggins & Trobst, 1999) in which various transactional influences impact both interactants as they resolve, negotiate, or disintegrate the interpersonal situation. Within this field, interpersonal behaviors tend to pull, elicit, invite, or evoke restricted classes of responses from the other, and this is a continual, dynamic transactional process. Thus, an interpersonal theory of personality emphasizes field-regulatory processes over self-regulatory or affectregulatory processes (Mitchell, 1988).

Sullivan (1948) initially conceived of reciprocal processes in terms of basic conjunctive and disjunctive forces that lead either to resolution or to disintegration of the interpersonal situation. He further developed this in the “theorem of reciprocal emotions,” which states that “integration in an interpersonal situation is a process in which (1) complementary needs are resolved (or aggravated); (2) reciprocal patterns of activity are developed (or disintegrated); and (3) foresight of satisfaction (or rebuff) of similar needs is facilitated” (Sullivan, 1953b, p. 129). Kiesler (1983) pointed out that although this theorem was a powerful interpersonal assertion, it lacked specificity, and “the surviving general notion of complementarity was that actions of human participants are redundantly interrelated (i.e., have patterned regularity) in some manner over the sequence of transactions” (p. 198).

Leary’s (1957) “principle of reciprocal interpersonal relations” provided a more systematic declaration of the patterned regularity of interpersonal behavior, stating “interpersonal reflexes tend (with a probability greater than chance) to initiate or invite reciprocal interpersonal responses from the ‘other’person in the interaction that lead to a repetition of the original reflex” (p. 123). Learning in interpersonal situations takes place in part because social interaction is reinforcing (Leary, 1957). Carson (1991) referred to this as an interbehavioral contingency process whereby “there is a tendency for a given individual’s interpersonal behavior to be constrained or controlled in more or less predictable ways by the behavior received from an interaction partner” (p. 191).

Describing Reciprocal Interpersonal Patterns

Structural models of interpersonal behavior such as the IPC and SASB have provided conceptual anchoring points and lexicons upon which more systematic description of the patterned regularity of reciprocal interpersonal processes can be articulated (e.g., Benjamin, 1974; Carson, 1969; Kiesler, 1983).

The Interpersonal Circle

Carson (1969) focused on the notion of interpersonal complementarity as the patterned regularity between two people that contributed to “felt security.” This notion is directly related to Sullivan’s conception of a resolved interpersonal situation as an outcome in which both persons’ needs are met via reciprocal patterns of activity leading to its likely recurrence. Anchoring his propositions within the IPC system, Carson first proposed that complementarity was based on the social exchange of status and love, as reflected in reciprocity for the vertical dimension (i.e., dominance pulls for submission; submission pulls for dominance) and correspondence for the horizontal dimension (friendliness pulls for friendliness; hostility pulls for hostility).

Kiesler’s (1983) seminal paper on complementarity significantly expanded these IPC-based conceptions in several ways. First, he recognized the continuous nature of the circular model’s descriptions of behavior, and he noted that because all interpersonal behaviors are blends of dominance and nurturance, the principles of reciprocity and correspondence could be employed to specify complementary points along the entire IPC perimeter. Thus, beyond the cardinal points of the IPC, it was asserted that (for example) hostile dominance pulls for hostile submission, friendly dominance pulls for friendly submission, and so forth, which can be further described by the lower-level taxa in these segments of the model. Second, Kiesler also incorporated Wiggins’(1979, 1980, 1982) conception of the IPC as a formal geometric model into his description of complementarity, whereby the distance from the center of the circle represents a dimension of intensity. That is, complementarity involves both the class of behaviors and their strength. Reciprocity on dominance, correspondence on nurturance, and equivalent intensity thus define complementary behaviors.

In addition, Kiesler (1983, 1996) defined two other broad classes of reciprocal interpersonal patterns anchored by the IPC model. When reciprocal interpersonal patterns meet one of the two rules of complementarity, he referred to this situation as an acomplementary pattern. In such a case, interactants may exhibit correspondence with regard to nurturance or reciprocity with regard to dominance, but not both. When interactants exhibit neither reciprocity on dominance nor correspondence on nurturance, he referred to this situation as an anticomplementary pattern. In Kiesler’s (1996) discussion of these three reciprocal patterns of interpersonal behavior, it is clear that they relate rather directly to the types of outcomes of interpersonal situations suggested by Sullivan. Complementary reciprocal patterns are considered to promote relational stability—that is, such interpersonal situations are resolved, they are mutually reinforcing, and they are recurring. Acomplementary patterns are less stable and instigate negotiation (e.g., toward or away from greater complementarity). Finally, anticomplementary patterns are the most unstable and lead to avoidance, escape, and disintegration of the interpersonal situation.

SASB

After developing his two circular models of maternal and child behavior, Schaefer (1961) suggested that relationships between the two surfaces could be the basis for articulating a theory of influence of maternal behavior on child behavior, stating

Bowlby (1951) has pointed out that both European and American investigators agree that the quality of parental care has great importance to the development of the child. Less agreement exists about how specific patterns of parent behavior are related to specific patterns of child behavior. One obstacle to the understanding of such relationships has been a lack of knowledge of the interrelations of the concepts within each universe [italics added]. For the purpose of discussion, let us accept the conceptual models presented here and attempt to develop hypotheses concerning the relationship of the two models [italics added]. (pp. 143–144)

Benjamin (1974, 1984, 1996a, 1996b) has extended Schaefer’s proposition by formally articulating a class of reciprocal interpersonal patterns defined by intersurface relationships within the SASB model, referred to as SASB predictive principles. The main predictive principles are complementarity, similarity, opposition, antithesis, and introjection, although others may be logically deduced (Schacht, 1994). It is important to note that these principles are not mutually exclusive from those anchored in the IPC model. The first four listed can also be articulated using the IPC. Complementarity implies the very same conditions for an interpersonal situation in both models with content (i.e., differing taxa) being the point of descriptive distinction. As Kiesler (1983) noted, similarity and opposition are specific forms of an acomplementary pattern as defined on the IPC. Antithesis is a form of anticomplementarity from the IPC perspective, again distinctly described using the SASB lexicon. Only introjection cannot be at least partially specified within the IPC model.

Complementarity is based on the relations between transitive and intransitive SASB surfaces; it reflects the typical transactional so-called pulls, bids, or invitations that influence dyadic interactants. It is defined when both members of a dyad are focused on the same person and exhibit comparable amounts of affiliation and autonomy. These can be identified by the numbers indicating the SASB surface (1, 2, or 3) and the cluster (1 through 8) as indicated in Figure 9.2. For example, a therapist focuses on her patient and empathically communicates that she notices an emotional shift (1-2: affirm). In response, the patient focuses on himself and tells the therapist of the associated perceptions, cognitions, wishes, fears, or memories associated with his current affective state (2-2: disclose). All possible complementary positions are marked by taxa appearing in the same locations on surface one and surface two (i.e., attack-recoil, blamesulk, control-submit, protect-trust, active love-reactive love, affirm-disclose, emancipate-separate, and ignore-wall off). Like the continuous nature of the IPC, the SASB model has several versions, differing in their level of segmentalization and thus precision in terms of their descriptive taxa and predictive principles.

Similarity is exhibited when an individual imitates or acts like someone else—that is, they occupy the same points on the same SASB surface. Imitation, modeling, and observational learning (Bandura, 1977) are important mechanisms in social learning theories that can be described by similarity. However, similarity has a different meaning if it is exhibited by two interactants in an interpersonal situation. If two people rigidly maintain similar positions at the same time, the situation will be rather unproductive—negotiation must occur for there to be much progress. A familiar example is a couple planning their weekend. If both attempt to control (demand their way), there is a power struggle. If both submit, little is accomplished as the pattern of What do you want to do?—I don’t know, I’ll do whatever you want cycles and stalls. In an occupational relationship, both boss and employee tend to focus on the employee. The boss controls (in a friendly, neutral, or hostile way) and the employee complies in kind (i.e., complementarity). In contrast, an employee who consistently tries to boss the boss (i.e., similarity) will not be an employee for long!

Points 180º apart describe opposition on each SASB surface. Opposing transitive actions are attack and active love, blame and affirm, control and emancipate, and protect and ignore. Opposing intransitive reactions are recoil and reactive love, sulk and disclose, submit and separate, and trust and wall off. Opposing introjected actions are self-attack and self-love, self-blame and self-affirm, self-control and selfemancipate, and self-protect and self-neglect.

The complementary point of an opposite is its antithesis. Given a particular transitive or intransitive behavior, the antithesis is identified by first locating the behavior’s opposite on the same surface, and then identifying its complement. That is, antithetical points differ in interpersonal focus and are 180º apart. Due to the impact of complementarity (i.e., a bid or invitation), the antithesis is the response that pulls for maximal change in an interpersonal relationship. For example, a psychotherapy patient treated by the first author would frequently sulk (2-6) when she experienced the therapist as not understanding or supporting her (e.g., I don’t know why I come here, this isn’t helping me). Rather than complement this with blame (1-6; e.g., If you don’t try to tolerate not getting exactly what you want from me, this won’t work), the antithetical affirming (1-2) response was enacted, (e.g., I can see that something I have done or failed to do has left you feeling pretty upset). The complement of affirm (1-2) is disclose (2-2). The patient would often visibly relax and communicate her frustration and disappointment. Thus, the antithesis of sulk (2-6) is affirm (1-2). Other antithetical pairs are emancipate and submit, active love and recoil, protect and wall off, control and separate, blame and disclose, attack and reactive love, and ignore and trust.

Introjection is based on the relations between the transitive and introject SASB surfaces and describes the circumstance where an individual treats him- or herself as he or she has been treated by important others.This reflects Sullivan’s view that important aspects of an individual’s self-concept are derived from reflected appraisals of others. That is, the person comes to conceptualize and treat himself in accordance with the ways important others have related to him or her. Common patterns often seen in psychotherapy include depressed patients who recall chronic blame and criticism from parents and now chronically self-blame, and patients with borderline personalities who were physically or sexually abused as children (perpetrator attack) and who now chronically self-attack via cutting or burning. As with complementarity, all introjected positions are marked by clusters in the same location but reflect the pairing of transitive and introject surface descriptors. These include attack and self-attack, blame and self-blame, control and self-control, protect and self-protect, active love and self-love, affirm and self-affirm, emancipate and self-emancipate, and ignore and self-neglect.

It is important to note that reciprocal interpersonal patterns anchored in either the IPC or SASB are neither inherently good nor inherently bad; they are value-free. In addition, we have tried to present them in their simplest form—as descriptors of behavior patterns that can be observed in interpersonal situations. A taxonomy of reciprocal interpersonal patterns is fundamental to contemporaneous analysis to account for transactional influences occurring in the interpersonal field and to developmental analysis to account for the enduring patterning of interpersonal situations that characterize a human life.

Contemporaneous Analysis of Human Transaction

In examining the immediate interpersonal situation, we may now use the taxonomies of interpersonal behavior and reciprocal interpersonal patterns to provide a contemporaneous analysis of human transaction. The most central pattern discussed previously is that of complementarity, and it is this reciprocal interpersonal pattern that anchors most theoretical discussions of interpersonal interaction. If we are to regard interpersonal behavior as influential or field regulatory, there must be some basic goals toward which our behaviors are directed. Sullivan (1953b) viewed the personification of the self to be a dynamism that is built up from the positive reflected appraisals of significant others, allowing for relatively anxiety-free functioning and high levels of felt security and self-esteem. The self-dynamism tends to be self-perpetuating due to both our awareness and organization of interpersonal experience (input), and the field-regulatory influences of interpersonal behavior (output). Sullivan proposed that both our enacted behaviors and our perceptions of others’ behaviors toward us are strongly affected by our self-concept. When we interact with others, we are attempting to define and present ourselves and trying to negotiate the kinds of interactions and relationships we seek from others. Sullivan’s (1953b) theorem of reciprocal emotion and Leary’s (1957) principle of reciprocal interpersonal relations have led to the formal view that what we attempt to regulate in the interpersonal field are the responses of the other. “Interpersonal behaviors, in a relatively unaware, automatic, and unintended fashion, tend to invite, elicit, pull, draw, or entice from interactants restricted classes of reactions that are reinforcing of, and consistent with, a person’s proffered self-definition” (Kiesler, 1983, p. 201; see also Kiesler, 1996). To the extent that individuals can mutually satisfy their needs for interaction that are congruent with their self-definitions (i.e., complementarity), the interpersonal situation remains integrated (resolved). To the extent that this fails, negotiation or disintegration of the interpersonal situation is more probable.

As noted previously, interpersonal theory includes intrapsychic elements. The contemporaneous description of the interpersonal situation utilizing either the IPC or SASB to delineate behavior and reciprocal patterns is not limited to the observable behaviors occurring between two people. Thus, interpersonal complementarity (or any other reciprocal pattern) should not be conceived of as some sort of stimulusresponse process based solely on overt actions and reactions (Pincus, 1994). Acomprehensive account of the contemporaneous interpersonal situation must somehow bridge the gap between the interpersonal (or overt) and the intrapsychic (or covert). Interpersonalists have indeed proposed many concepts and processes that clearly imply a rich and meaningful intrapsychic life (Kielser, 1996; Pincus, 1994), including personifications, selective inattention, and parataxic distortions (Sullivan, 1953a, 1953b), covert impacts (Kiesler et al., 1997), expectancies of contingency (Carson, 1982), fantasies and self-statements (Brokaw & McLemore, 1991), and cognitive interpersonal schemas (Foa & Foa, 1974; Safran, 1990a, 1990b; Wiggins, 1982). We agree with Safran’s (1992) conclusion that the “ongoing attempt to clarify the relationship between interpersonal and intrapsychic levels is what is needed to fully realize the transtheoretical implications of interpersonal theory” (p. 105). Much of the field is moving in this direction, as the relationship between the interpersonal and the intrapsychic is a common entry point for current integrative efforts (e.g., Benjamin, 1995; Florshiem et al., 1996, Tunis et al., 1990).

Kiesler’s (1986, 1988, 1991, 1996) interpersonal transaction cycle provides the most articulated discussion of the relations among overt and covert interpersonal behavior within interpersonal situations. He proposes that the basic components of an interpersonal transaction are (a) Person X’s covert experience of Person Y, (b) Person X’s overt behavior toward Person Y, (c) Person Y’s covert experience in response to Person X’s action, and (d) Person Y’s overt behavioral response to Person X. These four components are part of an ongoing transactional chain of events cycling toward resolution, further negotiation, or disintegration. Within this process, overt behavioral output serves the purpose of regulating the interpersonal field via elicitation of complementary overt responses in the other. The structural models of interpersonal behavior specify the range of descriptive taxa, whereas the motivational conceptions of interpersonal theory give rise to the nature of regulation of the interpersonal field. For example, dominant or controlling interpersonal behavior (e.g., Do it this way!) communicates a bid for status (e.g., I am an expert) that impacts the other in ways that elicit either complementary (e.g., Can you show me how?) or noncomplementary (e.g., Quit bossing me around!) responses in an ongoing cycle of reciprocal causality, mediated by covert and subjective experience.

In our opinion, the conceptions of covert processes mediating behavioral exchange have been a weak link in the interpersonal literature, reflecting much less consensus among theorists than do the fundamental dimensions and circular nature of structural models. The diverse conceptualizations proposed have not been comprehensively related to developmental analyses, nor have their influences on the observable interpersonal field been fully developed. In a significant step forward, Kiesler (1996) has synthesized many concepts (i.e., emotion, behavior, cognition, and fantasy) in developing the construct referred to as the impact message (see also Kiesler et al., 1997). Impact messages are fundamental covert aspects of the interpersonal situation, encompassing feelings (e.g., elicited emotions), action tendencies (pulls to do something; i.e., I should calm him down or I should get away), perceived evoking messages (i.e., subjective interpretations of the other’s intentions, desires, affect states, or perceptions of interpersonal situation), and fantasies (i.e., elaborations of the interaction beyond the current situation). Kiesler and his colleagues view the link between the covert and overt aspects of the interpersonal situation to be emotional experience. Impact messages are part of a “transactional emotion process that is peculiarly essential to interpersonal behavior itself” (Kiesler, 1996, p. 71). Impact messages are registered covertly by Person X in response to Person Y’s interpersonal behavior, imposing complementary demands on the behavior of Person X through elicited cognition, emotion, and fantasy. Notably, the underlying structure of impact messages parallels that of the IPC (Kiesler et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 1995), allowing for description of covert processes that are on a metric common with the description of overt interpersonal behavior.

In summary, contemporaneous analysis of the interpersonal situation accounts for the patterned regularity of interactions by positing that interpersonal behavior typically evokes a class of covert responses (impact messages) that mediate cycles of overt behavior—that is, patterned relational behavior occurs, in part, due to the field-regulatory influences of interpersonal behavior on covert experience and the subsequent mediation of overt action by evoked covert exprience. In our opinion, this is only part of the story. Covert responses are intrapsychic phenomena that give rise to subjective experience. It is clear that the nature of such covert responses—that is, feelings, action tendencies, interpretations, and fantasies—are not evoked completely in the moment due to interpersonal behavior of another, but rather arise in part from enduring organizational tendencies of the individual, as the following example illustrates.

Parataxic Integration of Interpersonal Situations

The covert impact messages evoked within a contemporaneous interpersonal transaction cycle are primarily associated with the overt behaviors of the interactants. It is assumed that interactants are generally aware of such covert experience, as the development of the self-report Impact Message Inventory (Kiesler & Schmidt, 1993) suggests. However, Sullivan (1953a) also suggested that other integrating tendencies— beyond those that are encoded within the proximal interpersonal field—often influence the interpersonal situation. Such parataxic distortions may play a more or less significant role in the covert experience of one or the other person in an interpersonal situation.

Clinical Example

Apsychotherapy patient treated by the first author entered her therapy session genuinely distraught and depressed. She reported that a person she labeled “an important friend” had ignored her during a recent social gathering and failed to attend a small celebration of her birthday. This was certainly no surprise to me, as this fellow had consistently behaved in an unreliable and invalidating manner toward my patient. However, it again appeared to be a surprise to her, and her disappointment was profound. The immediate interpersonal situation with this patient was quite familiar, and I decided our alliance was now sufficiently established to allow for an empathic effort to confront her continued unrealistic expectations of this fellow and to further examine how her attachment to him seemed to leave her vulnerable to ongoing disappointments.

I responded by saying, “I can understand that what has happened over the weekend has left you hurt, but I wonder why it is that despite repeated similar experiences with this ‘friend,’ you continue to remain attached to him and hope he will give you what you want? It seems to leave you very vulnerable.” My patient responded with sullen withdrawal, curtly remarking, “Now you’re yelling at me just like my mother always does!”

I am fairly certain that had the session been videotaped, there would be no increase in the decibel level of my voice during the intervention. And, an internal scan of my reaction to her report suggested helpful intent rather than countertransferential punitiveness. Nonetheless, my patient’s response clearly communicated that I was now berating her and putting her down, and that therapy was not supposed to go this way. This continued for several months—any effort I made to examine my patient’s contributions to her difficulties was rebuffed in a similar way. This continued to shape my therapeutic responses, leaving me hesitant to venture in this direction when my patient reported interpersonal difficulties. In other words, the repertoire of therapeutic behaviors I could provide became more and more limited by my patient’s rather rigid behaviors in our relationship. In Kiesler’s (1988) terminology, I was “hooked.”

Several things are apparent from this example. First, using interpersonal structural models to describe the contemporaneous therapeutic transaction, we would see that the relationship was often characterized by noncomplementary responses and by a movement away from an integrated therapeutic relationship. I would try to direct her attention toward herself in an empathic way, and in response my patient would withdraw and threaten to leave. Second, my patient’s response of sullen withdrawal was, however, quite complementary to her subjective experience of me as blaming and punishing. And third, the dynamic interaction between the overt and the covert aspects of our therapeutic transactions continuously exerted field-regulatory influence that allowed the therapy to continue. Too much “yelling and blaming” on my part would lead to a quick termination. My patient did not seem particularly aware of her bids to get me to back off, instead insisting she wanted my help with her depression and interpersonal difficulties.

In our opinion, this example highlights the challenges ahead for fully developing an integrative interpersonal theory of personality. In bridging the interpersonal and the intrapsychic, there are several limitations to contemporaneous analysis, three of which we discuss further in the next section.

Some Comments on Interpersonal Complementarity

The Locus of Influence

Safran (1992) is correct in pointing out that interpersonal theory’s bridge between the overt and the covert requires further development. It is possible that many interpersonal situations generate undistorted, proximal field-regulatory influences— that is, covert experience generally is consistent with overt experience and impact messages reflect reasonably accurate encoding of the interpersonal bids proffered by the interactants. Thus, all goes well, the interpersonal situation is resolved, and the relationship is stable. However, this is clearly not always the case, as the previous example suggests. When covert experience is inconsistent with the field-regulatory bids communicated via overt behavior, it is our contention that subjective experience takes precedence. That is, the locus of complementarity is internal and covert experience is influenced to a greater or lesser degree by enduring tendencies to elaborate incoming data in particular ways. The qualities of the individual that give rise to such tendencies have yet to be well articulated within interpersonal theory. Interpersonal theory can easily accommodate the notion that individuals exhibit tendencies to organize their experience in certain ways (i.e., they have particular interpersonal schemas, expectancies, fantasies, etc.), but there has been relatively little consensus on how these tendencies develop and how they impact the contemporaneous interpersonal situation.

The Problem of Complementarocentricity

Complementarocentricity can be defined as the tendency to place complementarity at the center of interpersonal theory and research. In our opinion, this overemphasis has limited the growth of theory. Three examples of complementarocentricity are as follows:

- What does failure to find empirical support for interpersonal complementarity mean? When empirical studies do not confirm the existence of complementarity, investigators often label it “a failure to statistically support complementarity” (e.g., Orford, 1986). Even when empirical investigations do find significant results (e.g., Gurtman, 2001), they are not indicative of 100% lawfulness. In our opinion, the answer to our question is that other reciprocal interpersonal patterns are also occurring in the interpersonal situation(s) under investigation.

- In perhaps the most influential articulation of complementarity, Kiesler (1983) defined all reciprocal patterns in relation to complementarity. That is, other forms of reciprocal interpersonal patterns are said to take either acomplementary or anticomplementary forms. We wonder if this has inadvertently promoted complementarity as a more fundamental reciprocal interpersonal pattern than it actually should be.

- In his encyclopedic review of complementarity theory and research, Kiesler (1996) presented 11 propositions to define and clarify the nature of, scope, and generizability of complementarity, and nine counterpoints to Orford’s (1986) famous critique of complementarity. In this work, Kiesler summarized important contributions by many interpersonalists emphasizing situational, personological, and intrapsychic moderators of complementarity (e.g., see Tracey, 1999), and suggested that significant attention be directed toward articulating when and under what conditions complementarity should and should not be expected to occur. Although this is exceptionally important, it continues to reflect complementarocentric thinking in that what is not recognized is that Kiesler’s (1996) 11 propositions, nine counterpoints, and continuing investigation of moderators serve to decentralize complementarity as the fundamental reciprocal interpersonal pattern by suggesting that its occurrence is more limited and contextualized. For example, consider Proposition 11 regarding “appropriate situational parameters” from Kiesler (1996): “The condition of complementarity is likely to obtain and be maintained in a dyadic relationship only if the following conditions are operative: a) the two participants are peers, b) are of the same gender, c) the setting is unstructured, and d) the situation is reactive (the possibility of reciprocal influence exists)” (p. 104). Considered alone, complementarity is thus suggested to be most applicable to understanding the unstructured interactions of same-sex peers. This is certainly important, but is perhaps not the core phenomenon of interest for a comprehensive theory of personality.

The Problem of Motivation

The two core theoretical assertions associated with interpersonal complementarity are Sullivan’s theorem of reciprocal emotion and Leary’s principle of reciprocal interpersonal relations. With regard to the former, we suggest that interpersonal theorists have overemphasized Sullivan’s first point (i.e., complementary needs are resolved or aggravated) and underemphasized his second point (i.e., reciprocal patterns of activity are developed or disintegrated). It is important to note that the needs involved are left undefined, and that the nature of satisfaction in the Sullivanian system involves a global sense of felt security marked by the absence of anxiety. Leary’s principle provided an important extension in its emphasis on interpersonal influence and reinforcement that shapes the nature of ongoing interpersonal situations. But to what end? What is behavior’s purpose? Traditionally, the cornerstone of complementarity has been the assertion that behavior is enacted to invite self-confirming reciprocal responses from others. We believe this has also been overemphasized in the interpersonal literature.

We agree that reciprocal interpersonal influence, reinforcement, and gratification are central to understanding human personality. This is reflected in the large number of psychological concepts that in some way reflect the notion of reciprocity. That is, individuals develop some consistently sought-after relational patterns and some strategies for achieving them. However, we do not believe that a single superordinate motive such as self-confirmation will succeed in comprehensively explaining how personality develops and is expressed.

Summary

Our discussion of interpersonal reciprocity and transaction has highlighted many of the unique strengths of interpersonal theory, as well as areas in which significant development and synthesis are necessary. In our view, interpersonal theory emphasizes relational functioning in understanding personality; this emphasis has led to the development of well-validated structural models that provide anchors to systematically describe interpersonal behavior and the patterned regularity of human transaction. Interpersonal theory has also emphasized field-regulatory aspects of personality in addition to the more traditional drive, self, and affectregulatory foci of most theories of personality. The combination of descriptive structural models and clear focus on the interpersonal situation provides a rich nomological net that has had a significant impact in psychology, particularly with regard to the classification of personological and psychopathological taxa and the contemporaneous analysis of human transactions and relationships. However, we also feel that the future of interpersonal theory will require continuing efforts to address (a) the intrapsychic or covert structures and processes involved in human transaction, (b) the overemphasis on complementarity as the fundamental reciprocal interpersonal pattern in human relationship, (c) the overemphasis on self-confirmation as the fundamental motive of interpersonal behavior, and (d) the lack of a comprehensive developmental theory to complement its strength in contemporaneous analysis.

The Future of Interpersonal Theory

We believe the future of interpersonal theory is bright. Addressing the four major issues previously noted will require interpersonal theorists to continue efforts at integrating interpersonal theory’s nomological net with the wisdom contained in the cognitive, psychodynamic, and attachment literature. Fortunately, this is already beginning to take place. Benjamin (1993, 1995, 1996a, 1996b) has initiated this with her interpersonal “gift of love” theory that integrates the descriptive precision of the SASB model with intrapsychic, motivational, and developmental concepts informed by attachment, cognitive, and object-relations theories.

Interpersonal Theory and Mental Representation

We have previously asked the question Where are interpersonal situations to be found? Our answer is that they are found both in the proximal relating of two persons and also in the minds of individuals. There are now converging literatures that suggest mental representations of self and other are central structures of personality that significantly affect perception, emotion, cognition, and behavior (Blatt, Auerbach, & Levy, 1997). Attachment theory refers to these as internal working models (Bowlby, 1969; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985), object-relations theory refers to these as internal object relations (Kernberg, 1976), and cognitive theory refers to these as interpersonal schemas (Safran, 1990a). Notably, theorists from each persuasion have observed the convergence in these concepts (Blatt & Maroudas, 1992; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999; Collins & Read, 1994; Diamond & Blatt, 1994; Fonagy, 1999; Safran & Segal, 1990; Westen, 1992). Benjamin (1993, 1996a, 1996b) has also proposed that mental representations of self and other are central to the intrapsychic interpersonal situation. She refers to these as important people or their internalized representations, or IPIRs. Thus, whether referred to as internal working models, internal object relations, interpersonal schemas, or IPIRs, psychological theory has converged in identifying mental representations of self and other as basic structures of personality.

In our opinion, the fundamental advantage of integrating conceptions of dyadic mental representation into interpersonal theory is the ability to import the interpersonal field (Wiggins & Trobst, 1999) into the intrapsychic world of the interactants (Heck & Pincus, 2001). What we are suggesting is that an interpersonal situation can be composed of a proximal interpersonal field in which overt behavior serves important communicative and regulatory functions, as well as an internal interpersonal field that gives rise to enduring individual differences in covert experience through the elaboration of interpersonal input.

In addition, Benjamin’s conception of IPIRs retains interpersonal theory’s advantage of descriptive precision based on the SASB model (Pincus et al., 1999). Benjamin (1993, 1996a, 1996b) proposes that the same reciprocal patterns that describe the interactions of actual dyads may be used to describe internalized relationships (mental representations of self and other) on the common metric articulated by the SASB model (see also Henry, 1997). In our view, this adds explanatory power for interpersonal theory to account for individuals’ enduring tendencies to organize interpersonal information in particular ways. Although the concept of the impact message is extremely useful in identifying the classes of covert cognitive, affective, and behavioral experiences of individuals, it does not necessarily account for the nature of individual differences in covert experiences. Benjamin’s IPIRs provide a way to account for the unique and enduring organizational tendencies that people bring to interpersonal situations—experiences that may underlie their covert feelings, impulses, interpretations, and fantasies in relation to others. Interpersonal theory proposes that overt behavior is mediated by covert processes. Psychodynamic, attachment, and cognitive theories converge with this assertion, and they suggest that dyadic mental representations are key influences on the subjective elaboration of interpersonal input. In our opinion, Benjamin has advanced interpersonal theory by incorporating mental representations explicitly into the conception of the interpersonal situation.

Returning briefly to our clinical example, recall that the patient consistently came into therapy reporting disappointments in her interpersonal relations. In telling her sad stories, she communicated her need to be consoled and nurtured. When she was asked to reflect on her own contributions to her disappointments, she became sullen and withdrawn. This reaction was a bid at negotiation, communicating a threat to leave in an effort to reestablish a reciprocal pattern of satisfying responses from her therapist. Why was this happening, given that the therapist attempted to provide recognition and consolation of her hurt feelings? Despite good therapeutic intentions, efforts to focus her attention on her own patterns seemed unhelpful. There was a clue in her report of her subjective covert experience. When the therapist turned the focus toward the patient’s contributions to her relational difficulties, he was experienced as similar to her mother. The proximal interpersonal field was no longer the primary source of her experience. There was now a second, parataxic integration of the situation that led to a covert experience that was driven by previous lived interpersonal experiences that now influenced the patient’s subjective experience; this became the primary mediating influence on her overt behavior. Despite her requests for help and consistent attendance in therapy, the patient was having difficulty organizing her experience of the therapist independently of her maternal IPIR. In our view, this example demonstrates that noncomplementary reciprocal interpersonal responses in the proximal interpersonal field may indicate significantly divergent experiences within the internal interpersonal field that can best be described by integrating interpersonal theory’s structural models with concepts of mental representation.

Development and Motivation

Adding conceptions of dyadic mental representation is not sufficient for a comprehensive interpersonal theory of personality. Sullivan (1964), Stern (1988), and others have suggested that the contents of the mind are in some way the elaborated products of lived interpersonal experience. A comprehensive interpersonal theory must account for how lived interpersonal experience is associated with the development of mental representation. In our opinion, Benjamin has provided the only comprehensive developmental approach to evolve from interpersonal theory.

Using SASB as the descriptive anchor (Figure 9.2), Benjamin (1993, 1996a, 1996b) has proposed three developmental copy processes that describe the ways in which early interpersonal experiences are internalized. The first is identification, which is defined as treating others as one has been treated; this is associated with the transitive SASB surface. To the extent that individuals strongly identify with early caretakers (typically parents), there will be a tendency to act toward others in ways that copy how important others have acted toward the developing person. The second copy process is recapitulation, which is defined as maintaining a position complementary to an IPIR; this is associated with the intransitive SASB surface and can be described as reacting as if the IPIR were still there. The third copy process is introjection, which is defined as treating the self as one has been treated. This is associated with the introject SASB surface and is related to Sullivan’s conceptions of “reflected appraisals” as a source of self-personification.

Identification, recapitulation, and introjection are not incompatible with Kiesler’s conception of covert impact messages. In fact, we suggest that the proposed copy processes can help account for individual differences in covert experience by providing developmental hypotheses regarding the origins of a person’s enduring tendencies to experience particular feelings, impulses, cognitions, and fantasies in interpersonal situations. For the patient described earlier, it seems that her experience of the therapist as yelling and blaming reflects (in part) recapitulation of her relationship with her mother. This in turn leads to a parataxic distortion of the proximal interpersonal field in therapy and noncomplementary overt behavior.

Although the copy processes help to describe possible pathways in which past interpersonal experience is internalized into mental structures (IPIRs), it is still insufficient to explain why early IPIRs remain so influential. The answer to this question requires a discussion of motivation. Whereas Sullivan’s legacy has led many interpersonal theorists to posit self-confirmation as the core motive underlying human transaction, Benjamin (1993) proposed a fundamental shift toward the establishment of attachment as the fundamental interpersonal motivation. In doing so, she has provided one mechanism to account for the enduring influence of early experience on mental representation and interpersonal behavior. Although a complete description of attachment theory is beyond the scope of this research paper, we agree that attachment to proximal caregivers in the early years of life is both an evolutionary imperative (e.g., Belsky, 1999; Bowlby, 1969; Simpson, 1999) and a primary organizing influence on early mental representation (Beebe & Lachmann, 1988a, 1988b; Bowlby, 1980; Stern, 1985).

Infants and toddlers must form attachments to caregivers in order to survive. Benjamin has suggested that the nature of the early interpersonal environment will dictate what must be done to establish attachments. These early attachment relationships can be described using the SASB model’s descriptive taxa, predictive principles, and copy processes. The primacy of relationships to IPIRs is thus associated with the need to maintain attachment to them even when not immediately present. Benjamin (1993) refers to this as maintaining “psychic proximity” to IPIRs. The need to maintain psychic proximity is organized around wishes for love and connectedness (secure attachment or AG on the SASB model), as well as fears of rejection and loss of love (disrupted attachment or DAG on the SASB model). The primacy of early attachment patterns and mental representations influencing current experience is consistent with psychodynamic and attachment theories. Bowlby (1980) suggested that internal working models act conservatively; thus, assimilation of new experience into established schemas is typical (see also Stern, 1988). Benjamin (1996a) suggested that “psychic proximity fulfills the organizing wish to receive love from the IPIR . . . acting like the IPIR, acting like the IPIR were present, or treating the self as would the IPIR can bring about psychic proximity” (p. 189).

Returning again to the patient described earlier, it was clear that she was ambivalently but strongly attached to her mother. She consistently experienced blame any time she attempted to convey interpersonal disappointments or bad feelings. Anything that disrupted her mother’s sense of control over the world was met with the accusation that the patient was being selfish and immature—and that it was the patient’s fault, so her feelings were not valid. In addition, she was told that if she didn’t stop causing so much trouble, her parents might divorce. It became clear that the patient had internalized a critical maternal IPIR. Whenever the patient was asked about her experience of self, she would inevitably begin her response with “My mother says that I am . . . ” or “My mother says it’s bad for me to feel this way.” When the therapist would try to explore the patient’s contributions to her interpersonal difficulties, it evoked recapitulation. Despite affirming and affliative efforts on the part of the therapist, the patient had a difficult time accommodating the new interpersonal input; instead she covertly experienced psychic proximity to the critical maternal IPIR and responded in kind. She experienced the therapeutic interpersonal situation as if the maternal IPIR were present, and she needed to back down rather than own her disappointments. To do otherwise would risk her attachment to her mother, painful as it was.

Concluding Propositions

Benjamin’s developmental and motivational extensions of interpersonal theory provide some of the richest advances to date. We see her work, along with Kiesler’s recent integration of emotion theory into the interpersonal transaction cycle, as solid evidence that interpersonal theory as originally conceived of by Sullivan has a vital and promising future as a fundamental and integrative approach to personality. In this vein we would like to close this research paper with a further extension of these contemporary works.

Interpersonal theorists are interested in understanding why certain reciprocal interpersonal patterns become prominent for an individual. Benjamin has made an important start by suggesting that a basic human motivation is attachment and that the interpersonal behaviors and reciprocal interpersonal patterns (described by interpersonal theory’s unique structural models) that help achieve attachment become fundamental to personality through internalization of relationships (characterized by the copy processes). She posits that the wish for attachment and the fear of its loss are universal, and that positive early environments lead to secure attachments and normal behavior (i.e., AG). If the developing person is faced with achieving attachment in a toxic early environment, behavior will be abnormal (DAG), but will develop in the service of attachment needs and be maintained via internalization.

We would like to extend this further in an effort to generate an interpersonal theory of personality that more broadly addresses issues of basic human motivation. It is our contention that the maturational trajectory of human life allows us to conceptualize many developmentally salient motives that may function to mediate and moderate current interpersonal experience. That is, reciprocal interpersonal patterns develop in concert with emerging motives that take developmental priority, thus expanding the goals that underlie their formation and maintenance. We can posit core issues likely to elicit the activation of central reciprocal patterns and their associated IPIRs, potential developmental deficits associated with early experiences, and unresolved conflicts that continue to influence the subjective experience of self and others. The output of such intrapsychic structures and processes for individuals are those consistently sought-after relational patterns and their typical strategies for achieving them (i.e., proximal and internal field regulation). These become the basis for the recurrent interpersonal situations that characterize a human life.

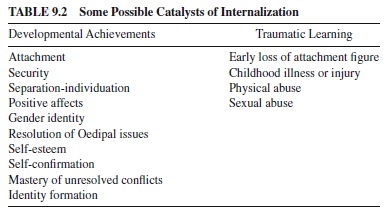

It is our view that what catalyzes and reinforces identification, recapitulation, and introjection is the organizing power of developmental achievements and traumatic stressors. Although interpersonalists have discussed differential “evoking power” of behavior due to situational constraints and the quality of interactions (i.e., moderators of complementarity), we believe such evoking power is limited in comparison to the catalyzing effects of major personality developments and their underlying motivational influences. At different points in personality development, certain motives become a priority. Perhaps initially the formation of attachment bonds and security are primary motivations; but later, separation-individuation, self-esteem, mastery of unresolved conflicts, and identity formation may become priorities (see Table 9.2). If we are to understand the reciprocity seeking, field-regulatory strategies individuals employ, we must learn what interpersonal behaviors and patterns were required to achieve particular developmental milestones. In this way, we see that what satisfies a need or achieves an important goal for a given individual is strongly influenced by his or her developmental history. In addition to developmental achievements, traumatic learning may also catalyze the internalization of patterns associated with coping responses to early loss of an attachment figure, severe physical illness in childhood, sexual or physical abuse, and so on.

Integrating the developmental and traumatic catalysts for internalization of reciprocal interpersonal patterns allows for greater understanding of current behavior. If individuals have the goal of individuating the self in the context of a current relationship in which they feel too enmeshed, they are likely to employ strategies that have been successful in the past. Some individuals have internalized hostile forms of differentiation such as walling off, whereas others have internalized friendly forms of differentiation such as asserting their opinions in an affiliative manner. The overt behavior of the other is most influential as it activates a person’s expectancies, wishes, and fears associated with current goals, needs, and motives; this will significantly influence their covert experience of impact messages. In our opinion, the most important goals, needs, and motives of individuals are those that are central to personality development.

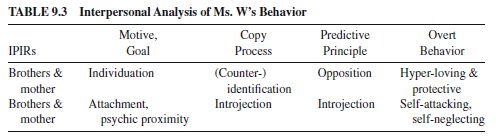

A brief example highlights this point and provides some clues as to why individuals may repeat maladaptive interpersonal behaviors over and over. Another psychotherapy patient treated by the first author was severely sexually and emotionally abused by multiple family members while she was growing up. The predictive principle of opposition to what she experienced as a child characterized her transitive actions towards others in the present. In all dealings with others she was hyper-loving and hyper-protective, even when clearly to her detriment. She compulsively exhibited such behaviors, even when treated badly by others. In therapy, it became clear that she counteridentified with her perpetrators and chronically exhibited the opposite pattern in order to maintain a conscious sense of individuation. It was as if she were saying, “If I allow myself to become even the slightest bit angry or blaming, it will escalate and I’ll be just like those who hurt me in the past.” Unfortunately, although she could shed tears for the victims of the holocaust and the victims of the recent epidemic of school shootings, she could not do so for herself. She had also introjected her early treatment within the family and continued to self-injure and ignore her own needs and basic human rights. Thus, although she consciously behaved in ways that individuated her from her abusers, she also abused and neglected herself in ways that unconsciously maintained attachment to her abusive IPIRs (see Table 9.3).