Sample Media and Child Development Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Using the Internet, watching television, and listening to music are the main leisure-time activities for most children and adults around the globe. Therefore, media and communication technology is perceived as a major influence on human development, interacting with genetic dispositions and the social environment. People are attracted to the media: to seek information, to be entertained, or to look for role models. The effect of media and communication technology on human development depends on several factors: (a) the psychological and social modes, which steer the motives of the media user; (b) personal predispositions; (c) the situational and cultural circumstances of the user; (d) kind, form, and content of the media and, (e) the time devoted to media use.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Media violence

Children in the twenty-first century are brought up in a media environment where the idea of communication convergence has become reality. There is a permanent cross-over between TVand Internetcontent; between computer-games and telecommunication; between editorial media contributions, and merchandising. Whereas most of this may serve socially constructive structures, i.e., increase information, facilitate communication, etc., it can also be applied in negative ways. Violence has always been a particularly successful media-market factor. It attracts high attention among male adolescents, its language is universal, and with the, often simple, dramaturgy, it can be more easily produced than the complex dialogue-based stories. Television was the dominating medium in the life of children during the second half of the twentieth century. It was often blamed for having negative effects on the young, but it undoubtedly also created numerous prosocial consequences, from programs such as ‘Sesame Street,’ ‘Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood’ in the USA, ‘Die Sendung mit der Maus’ in Germany, or ‘Villa Klokhuis’ in The Netherlands, to name but a few.

Television may still be popularly utilized, but in most Western children’s lives, it is no longer the case that one dominating medium is the ‘single source’ for information and passive entertainment. In the twentyfirst century, people are growing up in a ‘digital environment.’ With Internet-TV, and technologies, such as ‘replay,’ and with mobile phones connected to the World Wide Web, any content is potentially accessible at any given moment in any given situation. However, the media and media-effects debate in the twentieth century has predominantly been a Western, and more specifically an American Anglo-Saxon issue. However, relatively little research has been conducted concerning a far-reaching global approach to media violence. In the 1980s, Eron and Huesmann (1986) presented a cross-cultural study involving seven countries, including Australia, Israel, Poland, and the USA. In the 1990s, a group of researchers started an international analysis on the media environment of European children in the tradition of Hilde Himmelweit’s landmark 1958 study on television (Livingstone 1998). Groebel (2000) conducted a global study for UNESCO with 5,000 children from 23 countries participating in all regions of the world. The purpose was to analyze:

(a) the impact of different cultural norms on possible media effects;

(b) the interaction between media violence and real violence in the immediate environment of children, and

(c) the differences between world regions with a highly developed media landscape and those with only a few basic media available.

Children and adolescents have always been interested in arousing, and often even violent, stories and fairy tales (see, Singer and Singer 1990). With the arrival of mass media, film and television, however, the quantity of aggressive content daily consumed by these age groups increased dramatically. As real violence, especially among youths, is still growing, it seems plausible to correlate the two: media violence aggressive behavior. With more media developments such as video-recorders, computer games and the Internet, one can see a further increase in violent images, which attract great attention. Videos can present realistic torture scenes and even real murder. Computer games enable the user to actively simulate the mutilation of ‘enemies.’ The Internet has, apart from its prosocial possibilities, become a platform for child pornography, violent cults, and terrorist guidelines. Even with these phenomena, however, it is crucial to realize that the primary causes for aggressive behavior will still likely be found in the family environment, the peer groups, and in particular the social and economic conditions, in which children are raised (Groebel and Hinde 1991).

Yet media play a major role in the development of cultural orientations, world views and beliefs, as well as the global distribution of values and (often stereotyped) images. They are not only mirrors of cultural trends but can also channel them, and are themselves major constituents of society. Sometimes they can even be direct means of intergroup violence and war propaganda. It is important to identify their contribution to the propagation of violence, when one considers the possibilities of prevention.

With the technical means of automatization and, more recently, of digitization, any media content has become potentially global. Not only does individual news reach nearly any part of the world, but mass entertainment has also become an international enterprise. For example, American or Indian movies can be watched in most world regions. Much of what is presented contains violence. In literature, art, as well as in popular culture, violence has always been a major topic of human communication. Whether it is the Gilgamesh, a Shakespearean drama, the Shuihu Zhuan of Luo Guanzhong, Kurosawa’s Ran, stories of Wole Soyinka, or ordinary detective series, humankind seems always to be fascinated by aggression. This fascination does not necessarily mean that destructive behavior is innate, however, it draws attention, as it is one of the phenomena of human life which cannot be immediately explained and yet demands consideration of how to cope with it, if it occurs. Nearly all studies around the world show that men are much more attracted to violence than women. One can assume that, in a mixture of biological predispositions and gender role socializations, men often experience aggression as rewarding. It fits their role in society, but may once also have served as a motivation to seek adventure when exploring new territory or protecting the family and the group. Without an internal (physiological thrill seeking) and an external (status and mating) reward mechanism, men may rather have fled leaving their dependants unprotected. But apart from ‘functional’ aggression, humankind has developed ‘destructive’ aggression, mass-murder, hedonistic torture, and humiliation, which cannot be explained in terms of survival. It is often these which are distributed widely in the media. The type of media differ in impact. Audio-visual media are more graphic in their depiction of violence than are books or newspapers. They leave less freedom in the individual images, which the viewers associate with the stories. As the media become ever more perfect with the introduction of three dimensions (virtual reality) and interactivity (computer games and multimedia), and as they are always accessible and universal (video and Internet) the representation of violence ‘merges’ increasingly with reality.

Another crucial distinction is that between ‘contextrich’ and ‘context-free’ depictions of violence. Novels or sophisticated movies usually offer a story around the occurrence of violence: its background, its consequences. Violence as a pure entertainment product, however, often lacks any embedding in a context that is more than a cliched image of good and bad.

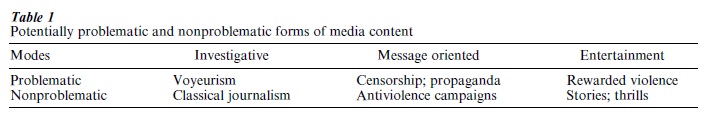

The final difference between the individual media forms concerns their distribution. A theatre play or a novel, are nearly always singular events. The modern mass media, however, create a timeand spaceomnipresence. Even here, a distinction between problematic and nonproblematic forms of media violence has to be made. A news program or a television documentary, which presents the cruelty of war and the suffering of its victims in a nonvoyeuristic way, is part of an objective investigation, or may even serve conflict-reduction purposes. Hate campaigns, on the other hand, or the ‘glorification of violence,’ stress the ‘reward’ characteristics of extreme aggression. In general, one can distinguish between three different modes of media content (see Table 1):

(a) purely investigative (typically news);

(b) message-oriented (campaigns, advertisement),

and

(c) entertainment (movies, shows).

Although, these criteria often may not be easy to determine, there are clear examples of each of the different forms. Reality television, or paparazzi activities may have to do with the truth but they also, in the extreme, influence this very truth through their own behavior (e.g., the discussion surrounding Princess Diana’s death). Through the informal communication patterns on the Internet, rumors also have become part of ‘serious’ news reporting, as the discussion around Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky has shown. Whether true or not, deviant groups and cults can influence the global information streams more efficiency than ever before. The cases of Serbia and Rwanda on the other hand have demonstrated the role which ‘traditional’ mass propaganda can still play in genocide.

Finally, many incidents worldwide indicate that children often lack the capacity to distinguish between reality and fiction and take for granted what they see in entertainment films, thus stimulating their own aggression (Singer and Singer 1990). If they are exposed permanently to messages which promote the idea that violence is fun or is adequate to solve problems and gain status, then the risk that they learn respective attitudes and behavior patterns is very high.

Many scientific theories and studies have dealt with the problem of media violence since the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of them originate in North America, Australia New Zealand or Western Europe. But increasingly, Asia, Latin-America and Africa are contributing to the scientific debate. The studies cover a broad range of different paradigms: cultural studies, content analyses of media programs, and behavioral research. However, the terms aggression and violence are defined exclusively here in terms of behavior, which leads to the harm of another person. For phenomena, where activity and creativity have positive consequences for those involved, other terms are used.

Recently, scientists have overcome their traditional dissent and have come to some common conclusions. They assume media effect risk, which depends on the message content, the characteristics of the media users, and their families, as well as their social and cultural environments. In essence, children are more at risk of being immediately influenced than adults. But certain effects, like habituation, do affect older age groups. While short-term effects may be described in terms of simple causal relationships, the long-term impact is more adequately described as an interactive process, which involves many different factors and conditions. Yet as the commercial and the political world strongly rely on the influence of images and messages (as seen in the billion-dollar turnover of the advertising industry or the important role of media in politics), it seems naive to exclude media violence from any effects probability.

The most influential theory on this matter is probably the Social Learning Approach by Albert Bandura (1977) and his colleagues. As most learning comes from observation of the immediate environment, it can be concluded that similar processes work through the media. Many studies have demonstrated that children either directly imitate what they see on the screen, or they integrate the observed behavior patterns into their own repertoire. An extension of this theory considers the role of cognitions. ‘If I see that certain behavior, e.g., aggression, is successful, I believe that the same is true in my own life.’ Groebel and Gleich (1993) and Donnerstein (1997) both show in European and US studies that nearly 75 percent of the aggressive acts depicted on the screen remain without any negative consequences for the aggressor in the movie, or are even rewarded. The Script Theory, among others, propagated by Huesmann and Eron (1986), assumes the development of complex world views (‘scripts’) through media influence. ‘If I over- estimate the probability of violence in real life (e.g., through its frequency on the TV-screen), I develop a belief system where violence is a normal and adequate part of modern society.’ The role of the personal state of the viewer is stressed in the Frustration–Aggression Hypothesis (see Berkowitz 1962). Viewers who have been frustrated in their actual environment, e.g., through having been punished, insulted, or physically deprived, ‘read’ the media violence as a signal to channel their frustration into aggression. This theory would explain why in particular, children in social problem areas are open to media-aggression effects.

The contrary tendency has been assumed in the Catharsis Theory, and later the Inhibition Theory by Seyrnour Feshbach. As in the Greek tragedy, aggressive moods would be reduced through the observation of similar tastes with others (substitute coping). Inhibition would occur when the stimulation of own aggressive tendencies would lead to learned fear of punishment and thus contribute to its reduction. While both approaches may still be valid under certain circumstances, they have not been confirmed in the majority of studies, and their original author, Feshbach, now also assumes a negative effects risk.

Much of the fascination of media violence has to do with physiological arousal. The action scenes, which are usually part of media violence, grab the viewer’s attention and create at least a ‘kick,’ most usually among males. At the same time, people tend to react more aggressively in a state of arousal. This would again explain why arousing television scenes lead to higher aggression among frustrated angered viewers, as Zillmann (1971) explains in his Excitation Transfer Theory. In this context, it is not the content but the formal features, sound, and visual effects that would be responsible for the result. Among others, Donnerstein, Malamuth, and Linz have investigated the effect of long-term exposure to extremely violent images. Men in particular get used to frequent bloody scenes and their empathy towards aggression victims is reduced. The impact of media violence on anxiety has also been analyzed. Gerbner (1993) and Groebel (Groebel and Hinde 1991) have both demonstrated in longitudinal studies, that the frequent depiction of the world as threatening and dangerous leads to more fearsome and cautious attitudes towards the actual environment. As soon as people are already afraid or lack contrary experiences, they develop an Anxious World View, and have difficulties in distinguishing between reality and fiction. Cultural studies have discussed the role of the cultural construction of meaning. The decoding and interpretation of an image depends on traditions and conventions. This could explain why an aggressive picture may be ‘read’ differently, e.g., in Singapore than in Switzerland, or even within a national culture by different groups. These cultural differences have definitely to be taken into account. Yet, the question is, whether certain images can also immediately create emotional reactions on a fundamental (not culture-bound) level and to what extent the international mass media have developed a more homogeneous (culture-overspanning) visual language. Increasingly, theories from a non-Anglo-Saxon background have offered important contributions to the discussion.

Groebel has formulated the Compass Theory; depending on already existing experiences, social control, and the cultural environment, media content offers an orientation, a frame of reference which determines the direction of one’s own behavior. Viewers do not necessarily adapt simultaneously to what they have observed; but they measure their own behavior in terms of distance to the perceived media models. If extreme cruelty is ‘common,’ just ‘kicking’ the other seems to be innocent by comparison, if the cultural environment has not established a working alternative frame of reference (e.g., social control, values).

In general, the impact of media violence depends on several conditions: media content—roughly 10 acts of violence per hour in average programming (see the US National TV Violence Study, by Donnerstein 1997); media frequency; culture and actual situation; and the characteristics of the viewer and his family surrounding. Yet, as the media now are a mass phenomenon, the probability of a problematic combination of these conditions is high. This is demonstrated in many studies. Based on scientific evidence, one can conclude that the risk of media violence prevails.

2. Media use

2.1 Global Statistics

Of the school areas in the UNESCO sample, 97 percent can be reached by at least one television broadcast channel. For most areas the average is four to nine channels (34 percent); 8.5 percent receive one; 3 percent two channels; 9 percent three channels; 10 percent 10 to 20 channels, and 18 percent more than 20 channels.

In the global sample, 91 percent of the children have access to a TV set, primarily at home. Thus, the screen has become a universal medium around the world. Whether it is the ‘favelas,’ a South Pacific island, or a skyscraper in Asia, television is omnipresent, even when regions where television is not available, are considered. This result justifies the assumption that it is still the most powerful source of information and entertainment outside face-to-face communication. Even radio and books do not have the same distribution (91 and 92 percent, respectively).

The remaining media follow some way behind: newspapers, 85 percent; tapes (e.g., cassette), 75 percent; comics, 66 percent; videos, 47 percent; videogames, 40 percent; personal computers, 23 percent; Internet, 9 percent.

Children spend an average of 3 hours daily in front of the screen. That is at least 50 percent more time spent with this medium than with any other activity: homework (2 hours), helping the family (1.6 hours); playing outside (1.5 hours); being with friends (1.4 hours); reading (1.1 hours); listening to the radio (1.1 hours); listening to tapes CDs (0.9 hours), and using the computer (0.4 hours).

Thus, television still dominates the life of the children around the globe.

There is a clear correlation between the presence of television and reporting action heroes as favorites. The favorites in Africa are pop stars musicians (24 percent), with Asia the lowest (12 percent). Africa has also high rankings for religious leaders (18 percent), as compared to Europe Canada (2 percent); LatinAmerica (6 percent), and Asia (6 percent). Military leaders score highest in Asia (9.6 percent), and lowest in Europe Canada (2.6 percent). Journalists score well in Europe Canada (10 percent), and low in LatinAmerica (2 percent). Politicians rank lowest in Europe (1 percent), and highest in Africa (7 percent). Again, there may be a correlation with the distribution of mass media: the more TV, the higher the rank of massmedia personalities, and the lower the traditional ones (politicians, religious leaders). There is a strong correlation between the accessibility of modern media and the predominant values and orientations.

At this stage, we can summarize the role of the media for the perception and application of aggression as follows:

(a) Media violence is universal. It is presented primarily in a rewarding context. Depending on the personality characteristics of the children, and depending on their everyday life experiences, media violence satisfies different needs.

(b) It ‘compensates’ own frustrations and deficits in problem-areas.

(c) It offers ‘thrills’ for children in a less problematic environment.

(d) For boys, it creates a frame of reference for ‘attractive role-models.’

There are many cultural differences, and yet, the basic patterns of the media violence implications are similar around the world. Individual movies are not a problem. However, the extent and omnipresence of media violence contributes to the development of a global aggressive culture. The ‘reward-characteristics’ of aggression are promoted more systematically than nonaggressive ways of coping with life. Therefore, the risk of media violence prevails.

The results demonstrate the omnipresence of television in all areas of the world. Most children around the globe seem to spend most of their free time with the medium. What they get is a high portion of violent content.

Combined with the real violence, which many children experience, there is a high probability that aggressive orientations are promoted, rather than peaceful ones. But also in lower-aggression areas, violent media content is presented in a rewarding context. Although children cope differently with this content in different cultures, the transcultural communality of the problem is the fact that aggression is interpreted as a good problem-solver for a variety of situations.

Children desire a functioning social and family environment. As they often seem to lack these, they seek role models, which offer compensation through power and aggression. This explains the universal success of movie characters like The Terminator. Individual preferences for films of this nature are not the problem. However, when violent content becomes a common phenomenon up to the occurrence of an aggressive media environment, the probability that children will develop a new frame of reference, and that problematic predispositions are channeled into destructive attitudes and behavior, increases immensely.

Bibliography:

- Bandura A 1977 Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs,

- Berkowitz L 1962 Violence in the mass media. Paris-Stanford Studies in Communication. Stanford University, Stanford, CA, pp. 107–37

- Donnerstein E 1997 National Violence Study. University of California, Santa Barbara, CA

- Feshbach S 1985 Media and delinquency. In: Groebel J (ed.) Proceedings of the 7th United Nations Congress Symposium on the Pre ention of Crime; Scientific Aspects of Crime Pre ention. Milan

- Gerbner G 1993 Violence in cable-originated tele ision programs: A report to the national cable tele ision association. NCTA, Washington, DC

- Gerbner G, Gross L 1976 Living with television: Violence profile. Journal of Communication 26: 173–99

- Groebel J (ed.) 1997 New media developments, Trends in Communication, 1. Boom, Amsterdam

- Groebel J, Gleich U 1993 Gewaltprofil des deutschen Fernsehens [Violence Profile of German Television]. Landesanstalt fur Rundfunk Nordrhein-Westfalen, Leske and Budrich, Leverkusen, Germany

- Groebel J, Hinde R A (eds.) 1991 Aggression and War. Their

- Biological and Social Bases. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Groebel J, Smit L 1997 Gewalt im Intemet [Violence on the Internet]. Report for the German Parliament. Deutscher Bundestag, Bonn, Germany

- Huesmann L R (ed.) 1994 Aggressi e Beha ior: Current Perspecti es. Plenum, New York

- Huesmann L R, Eron L D 1986 Tele ision and the Aggressi e Child: A Cross-national Comparison, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Livingstone S 1998 A European Study on Children’s Media En ironment. World Summit on Children’s Television, London

- Malamuth N 1988 Do Sexually Violent Media Indirectly Contribute to Antisocial Beha ior. Academic Press, New York, Vol. 2

- Singer J L, Singer D G 1990 The House of Make-Belie e. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Zillmann D 1971 Excitation transfer in communication mediated aggressive behavior. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology 7: 419–34