Sample Uses of Media Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Mass media (mainly TV, newspapers, magazines, radio, and now Internet) have been found to perform a variety of ‘functions’ for the audiences who use them (Wright 1974). Among the major controversies in the literature on media use (which is limited by most research reviewed below having been conducted in the USA) is the question of how much each medium’s content informs rather than simply entertains its audience. Television is often assumed to serve primarily as an entertainment medium while print media are looked to for information.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The information vs. entertainment distinction may overlook more long-term uses and subtler or latent impacts, such as when media content is used as a stimulus for subsequent conversation or for consumer purchases. Such latter impacts also can affect longer range cultural values and beliefs, such as fostering materialism or the belief that commercial products can solve personal problems.

The media may also perform interrelated information or entertainment ‘functions,’ as when viewers learn headline information about a news story on television, but then seek in-depth information from newspapers or magazines. Much literature has been devoted to studying the diffusion of stories of landmark events (Budd et al. 1966), such as the Kennedy assassination or the death of Princess Diana—or the audience response to events created for the media themselves (e.g., Roots, Kennedy–Nixon and other presidential debates).

There is also the more general question of how the various media complement, compete with, or displace each other to perform these functions, particularly in terms of user or audience time. As each new medium is introduced, it performs functions similar to those performed by existing media. This is referred to as ‘functional equivalence’ (Weiss 1969). Unless individuals devote more overall time to media use, time spent on older media must be displaced. Some researchers argue that overall media time tends to remain constant so that displacement is likely if new media become popular (Wober 1989). To the extent that a new medium like television performs the entertainment function in a way that is more compelling and attractive (than existing media like radio, magazines, movies, or print fiction), according to this ‘functional equivalence’ argument those earlier media will suffer losses of audience time and attention. Time displacement is becoming a central concern in research on Internet use, as researchers seek to gauge its potential to displace use of TV, radio, or newspapers.

1. Methods

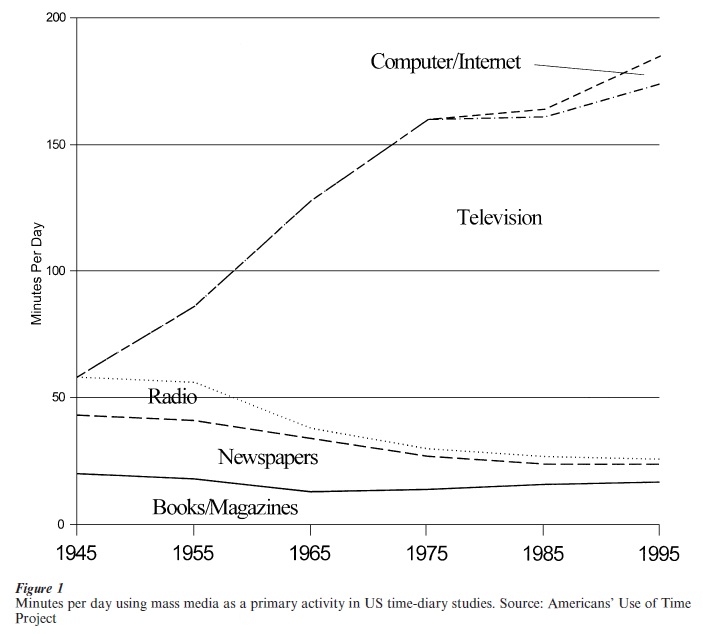

Media use issues raise various questions about study methodology and measurement, since research results can vary depending on the methods used. For example, people’s media use can be measured by electronic meters attached to their TVs (or computers), by ‘beepers’ attached to the person’s clothing, by inperson or video monitoring, or by simply asking these people questions about their media use. Survey questions generally have the value of being more flexible, more global, and more economical than monitoring equipment, but there are problems of respondent reliability and validity. Long-range usage questions (e.g., ‘How many hours of TV did you watch in a typical week?’) may reveal more about a respondent’s typical patterns, but they are limited by that person’s memory or recall. Shorter-range questions (e.g., ‘How many hours of TV did you watch yesterday?’) appear to overcome these problems, but the day may not be typical of long-range usage. There is evidence that in the shorter range, complete time diaries of all the activities the person did on the prior day may be needed to capture the full extent of media use engaged in; an example of the power of the diary approach to reflect the full extent of media impact is given in Fig. 1.

In much the same way, different results are obtained when different types of questions are asked about the ways and purposes for which the media are used and how media usage has affected audiences. Thus different results are obtained when one asks respondents which news medium has informed them most compared to a more ‘microbehavioral’ approach, in which respondents are asked actual information questions and these answers are then correlated with the extent of each medium used (Davis and Robinson 1989)—or when respondents are asked to keep an information log of each new piece of information obtained and where how it was obtained.

Similarly, different results and perspectives obtain when respondents are asked about the gratifications they receive from particular types of media content (such as news or soap operas) rather than the ‘channels approach’ (see below), which focuses more on respondents’ preference for, and habitual use of, specific media to serve certain functions.

2. Perspectives on Media Use

The four topic areas covered below mainly concern quantative studies of media audiences. Qualitative studies of media audiences since the 1980s have become increasingly popular in cultural studies and communication studies.

2.1 Uses and Gratifications

Research on media use has been dominated by the uses and gratifications perspective since the 1970s (Rubin 1994). This perspective asserts that individuals have certain communication needs and that they actively seek to gratify those needs by using media. This active use of media is contrasted with older audience theories in which individuals were assumed to be directly affected by passively consumed media content.

The most commonly studied needs are information, entertainment, and ‘social utility’ (discussing media content with others or accessing media content to be used in subsequent conversation). Individuals who experience gratification when they use media are likely to develop a media use habit that becomes routine. Without such gratifications habits will not be developed and existing habits could erode. Across time, gratifications become strongly associated with high levels of media use.

Various forms of gratification are measured by different sets of questionnaire items. Individuals have been found to vary widely in their communication needs and gratifications, with the strongest and most universal communication need satisfied by media repeatedly found for entertainment, then information, and then social utility. Women tend to report stronger need for social utility than men and their use of media is more likely to reflect this need. The central assertions of uses and gratifications theory have been confirmed in a very large number of studies that have been done, focusing on different types of media content ranging from TV news, political broadcasts, and sports programs, to soap operas and situation comedies. Frequency of media use is almost always found to be strongly correlated with reports of gratification. Persons who report more social utility gratification tend to be more socially active. Persons who report more information gratification tend to be better educated and have higher social status.

Uses and gratifications research has been unable to establish strong or consistent links between gratification and subsequent effects (Rubin 1994). For example, persons who report strong entertainment gratification when viewing soap operas should be more influenced by such programs, and persons who report strong information gratification when viewing TV news should learn more.

However, it has proved very difficult to locate such effects consistently; and when effects are found, they tend to be weak, especially in relation to demographic factors. One reason for this may be that most research has been done using one-time, isolated surveys. Another is that individuals may have a limited consciousness of the extent to which media content gratifies them. To increase the accuracy of gratification self-reports, researchers have sought to identify contingent conditions or intervening variables that would identify gratification effects. Other researchers have argued that the type of media use has to be considered, such as routine or ritualized use of media vs. conscious or instrumental use. These efforts have had modest success. Some researchers reject the idea of looking for effects, arguing that the focus of uses and gratifications research should be on the media use process, without concern for the outcome of this process.

2.2 Channels

Recently, a channels approach to media research has emerged (Reagan 1996) that assumes that people develop ‘repertoires’ of media and of the channels into which such media are divided. These ‘repertoires’ consist of sets of channels that individuals prefer to use to serve certain purposes. Channels are rank ordered within repetoires. If all channels are equally accessible, then more preferred channels will be used. For example, some individuals may have a channel repertoire for national news which prioritizes network TV news channels first (e.g., ABC first, CBS second, NBC third), ranks radio news channels second, newspaper channels third, and so on. If they miss a network news broadcast, they will turn next to radio channels and then to newspapers. Reagan (1996) reports that these repertoires are larger (include more channels) when individuals have strong interests in specific forms of content. When interest is low, people report using few channels.

The channels approach was developed in an effort to make sense of the way that individuals deal with ‘information-rich’ media environments in which many media with many channels compete to provide the same services. When only a handful of channels is available, there is no need for people to develop repertoires as a way of coping with abundance. In a highly competitive media environment with many competing channels, the success of a new channel (or a new medium containing many channels) can be gauged first by its inclusion in channel repertoires and later by ranking accorded to these channels. For example, research shows that the Internet is increasingly being included in channel repertoires for many different purposes ranging from national news and health information to sports scores and travel information. In most cases, Internet channels are not highly ranked but their inclusion in channel repertoires is taken as evidence that these channels are gaining strength in relation to other channels.

2.3 Information Diffusion

2.3.1 Diffusion of news about routine events.

Perhaps the most widely believed and influential conclusion about the news media is that television is the public’s dominant source for news. Indeed, most survey respondents in the USA and other countries around the world clearly do perceive that television is their ‘main source’ for news about the world, and they have increasingly believed so since the 1960s. As noted above, that belief has been brought into question by studies that examine the diffusion of actual news more concretely. Indeed, Robinson and Levy (1986) found that not one of 15 studies using more direct approaches to the question found TV to be the most effective news medium; indeed, there was some evidence that TV news viewing was insignificantly associated with gains in information about various news stories. While the choice, popularity, and variety of news media have changed notably since the early 1990s, much the same conclusion—that newspapers and other media were more informative than television—still held in the mid-1990s.

That does not mean that news viewers do not accrue important news or information from the programs they view. Davis and Robinson (1989) found that viewers typically comprehend the gist of almost 40 percent of the stories covered in a daily national newscast, despite the failure of TV news journalists to take advantage of the most powerful factors related to viewer comprehension (especially redundancy). However, these information effects seem short-lived, as the succeeding days’ tide of new news events washes away memories of earlier events. It appears that print media—with their ability for readers to provide their own redundancy (by rereading stories or deriving cues from the story’s position by page or space)—have more sticking power. Moreover, the authors found that more prominent and longer TV news stories often conveyed less information because these stories lacked redundancy or tended to wander from their main points.

These results were obtained with national newscasts and need to be replicated with local newscasts, which are designed and monitored more by ‘news consultants’ who keep newscasters in more intimate touch with local audience interests and abilities than at the national network level. The declining audience for network flagship newscasts since the mid-1980s further suggests that viewers’ perceptions of the ‘news’ for which TV is their major source may be news at the local level.

2.3.2 Diffusion of news about critical events.

Another approach to news diffusion research has focused on atypical news events that attract widespread public attention and interest. Kraus et al. (1975) argued that this ‘critical events’ approach developed because researchers found that the news diffusion process and its effects are radically different when critical events are reported. Early critical events research focused on news diffusion after national crises such as the assassination of President Kennedy or President Eisenhower’s heart attack. One early finding was that interpersonal communication played a much larger role in diffusion of news about critical events, often so important that it produced an exponential increase in diffusion over routine events. Broadcast media were found to be more important than print media in providing initial information about critical events.

In Lang and Lang’s (1983) critical events analysis of news diffusion and public opinion during Nixon’s Watergate crisis, both news diffusion and public opinion underwent radical changes for many months. The Langs argued that this crisis had two very different stages, first during the 1972 election campaign and second after the campaign ended. Watergate was largely ignored during the election campaign and its importance was marginalized, news diffusion about Watergate resembling diffusion of routine campaign information. Knowledge about Watergate was never widespread and this knowledge actually declined from June 1972 until November 1972. But the 1973 Senate hearings drew public attention back to it with an unfolding sequence of events that ultimately led to erosion of public opinion support for Nixon.

Other researchers have argued that the media increasingly create artificial crises in order to attract audiences. News coverage is similar to what would be used to report critical events. This means that the importance of minor events is exaggerated. For example, Watergate has been followed by an unending series of other ‘gates’ culminating in Whitewatergate, Travelgate, and Monicagate. Some researchers argue that coverage of the O. J. Simpson trial was exaggerated to provoke an artificial media crisis. Research on these media crises indicates that they do induce higher levels of news diffusion and that frequently the role of interpersonal communication is stimulated beyond what it would be for routine event coverage. Knowledge of basic facts contained in news coverage becomes widespread without the usual differences for education or social class. One interesting side-effect is that public attitudes toward media coverage of such events has been found to be mixed, with less than half the public approving of the way such events are covered. There is growing evidence that the public blames news media for this coverage and that this is one of the reasons why public esteem of the media has been declining.

2.4 Time Displacement

2.4.1 Print.

Earliest societies depended on oral traditions in which information and entertainment, and culture generally, were transmitted by word of mouth. While their large gatherings and ceremonies could reach hundreds and in some cases thousands of individuals simultaneously, most communication occurred in face-to-face conversations or small groups. The dawn of ‘mass’ media is usually associated with the invention of the printing press. Print media posed a severe challenge to oral channels of communication. As print media evolved from the publication of pamphlets, posters, and books through newspapers and journals magazines, we have little empirical basis for knowing how each subsequent form of print media affected existing communication channels. We do know that print channels were held in high regard and that they conferred status on persons or ideas (Lazarsfeld and Merton 1948). Print media are thought to have played a critical role in the spread of the Protestant Reformation and in promoting egalitarian and libertarian values. Government censorship and regulation of print media became widespread in an effort to curtail their influence.

Based on current research findings of the ‘more … more’ principle described below, however, we suspect—for simple reasons of the literacy skills involved—that the popularity of older forms of print media such as pamphlets and books made it possible for later media to find audiences. Existing book readers would have been more likely to adapt and spend time reading journals and newspapers than would book nonreaders. Some researchers argue that Protestantism was responsible for the rise of print channels generally because Protestants believed that all individuals should read the Bible on their own. This led them to focus on teaching literacy. Print media were more widespread and influential in Protestant Northern Europe than predominantly Catholic Southern Europe during the early part of the seventeenth century.

2.4.2 Cinema and radio.

Early in the twentieth century, movies quickly became a popular way of spending time; and anecdotal reports suggest that weekly moviegoing had become a ritual for most of the US population by the 1920s. The impact of movies was widely discussed, but there are no contemporary reports about whether the movies were frequented more or less by readers of books, magazines, or newspapers—although one might suspect so for the simple economic reason that the more affluent could afford both old and new media. Movies were especially attractive to immigrant populations in large cities because many immigrants were not literate in English.

Much the same could be expected for the early owners of radio equipment in the 1920s. Whether radio listeners chose to go to the movies, or read, less than nonowners again appears largely lost in history. By the 1930s and 1940s, however, radio appears to have been used for at least an hour a day; but it is unclear how much of that listening was performing the ‘secondary activity’ function that it has become today—rather than the radio serving as the primary focus of attention, as suggested in period photographs of families huddled around the main set in the living room.

2.4.3 Television.

Greater insight into the time displacements brought about by TV was provided by several network and non-network studies, which documented notable declines in radio listening, moviegoing, and fiction reading among new TV owners. These were explained as being media activities that were ‘functional equivalents’ of the content conveyed by these earlier media (Weiss 1969).

However carefully many of these studies were conducted (some employing panel and other longitudinal designs, as in the ‘Videotown’ study), they were limited by their primary focus on media activities. Using the full-time diary approach and examining a sample of almost 25,000 respondents across 10 societies at varying levels of TV diffusion, Robinson and Godbey (1999) reported how several nonmedia activities were affected by TV as well, with TV owners consistently reporting less time in social interaction with friends and relatives, in hobbies, and in leisure travel. Moreover, nonleisure activities were also affected, such as personal care, garden pet care and almost 1.5 hours less weekly sleep—activities that do not easily fit into the functional equivalence model. The diaries of TV owners also showed them spending almost four hours more time per week in their own homes and three hours more time with other nuclear family members.

Some of TV’s longer-term impacts did not show up in these earliest stages of TV. For example, it took another 10 to 15 years for TV to reduce newspaper reading time, which it has continued to do since the 1960s—primarily it seems because of sophisticated local TV news advisors. Another explanation is that TV’s minimal reliance on literacy skills tends to erode over time, and that it took 15 years for literacy skills to erode to the point where more people found it less convenient to read newspapers. In contrast, since the initial impact of TV in the 1950s, time spent on radio listening as a secondary background activity has increased by almost 50 percent and books, magazines, and movies have also recaptured some of their original lost audiences. There has been a dramatic proliferation of specialty magazines to replace the general interest magazines apparently made obsolete by television. Some researchers argue that these magazines disappeared because advertisers deserted them in favor of TV. In terms of nonmedia activities, Putnam (2000) has argued that TV has been responsible for a loss in time for several ‘social capital’ activities since the 1960s.

Figure 1 shows the relative declines in primary activity newspaper reading and radio listening times since the 1960s, both standing out as free-time activities that declined during a period in which the free time to use them expanded by about five hours a week. TV time as a secondary activity has also increased by about two hours a week since the 1960s.

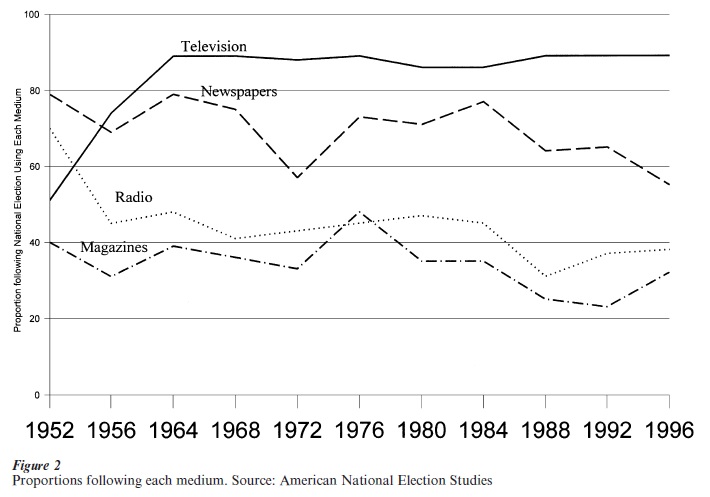

A somewhat different perspective on TV’s longterm effect on media use is afforded by time series data on media use for the particular purpose of following elections. As shown in Fig. 2, TV rapidly had become the dominant medium for following electoral politics by 1964. Since then each of the other media has suffered declines in political use as TV use has maintained its nearly 90 percent usage level; more detailed data would probably show greater TV use per election follower across time as well. However, the three other media have hardly disappeared from people’s media environment and continue to be used as important sources by large segments of the electorate in Fig. 2, such as radio talk shows in the 1990s.

What these electoral data also show, however, is that the composition of the audience for these media has changed as well. Newspapers and magazines no longer appeal as much to better educated individuals as they once did; much the same is true for TV political usage. Age differences are also changing, with newspaper and TV political followers becoming increasingly older, while radio political audiences are getting proportionately younger.

At the same time, there are clear tendencies for media political audiences to become more similar to one another. Greater uses of all media for political purposes are reported by more educated respondents, particularly newspapers and magazines. This finding appears to be consistent with the channel repertoire approach since educated respondents likely have more interest in politics and thus develop a larger channel repertoire. Older respondents report slightly more political media use than younger people, and men more than women, and people who use one political medium are more likely to use others as well.

These are patterns for political content, however; and notably different patterns would be found if the content were fashion or rock country music and not politics. Yet there is still a general tendency for users of newspapers to use other media more (particularly for broad information purposes), bringing us back again to the overriding ‘more … more’ pattern of media use.

3. Conclusions

A recurrent and almost universal theme in media use research is the tendency of the media information rich to become richer following the ‘more … more’ model. Users of one medium are more likely to use others, interested persons develop larger channel repertoires, and the college educated become more informed if news content is involved according to the ‘increasing knowledge gap hypothesis’ (Gaziano 1997). Robinson and Godbey (1999) have found more general evidence of this ‘Newtonian model’ of behavior in which more active people stay in motion while those at rest stay at rest. The increasing gap between the ‘entertainment rich and poor’ may likely be found as well, as when users of TV for entertainment can watch more entertainment programs when more channels or cable connections become available. Persons who have strong communication needs and experience more gratification from media tend to make more use of media.

A prime outcome of media use then may be to create wider differences in society than were there prior to the media’s presence. As media channels proliferate, people respond by developing repertoires that enable them to use these channels efficiently to serve personal purposes. These repertoires vary widely from person to person and strongly reflect the interests of each individual.

The Internet and home computer promise to bring literally millions of channels into peoples’ homes. How will people deal with this flood of channels? Existing research on Internet and computer use indicate that unlike early TV users, Internet computer users are not abandoning older channels in favor of Internet-based channels. Instead, they are merely adding Internet channels to existing repertoires and increasing their overall use of media (Robinson and Godbey 1999). These new media users also report the same amount of TV viewing, perhaps even increasing their viewing as a secondary activity while they are online. It is probably too early to conclude that these elevated levels of total media use will persist even after the Internet has been widely used for several years. The ease with which Internet use can coincide with use of other media will make it difficult to arrive at an accurate assessment of its use in relation to other media. In fact, some futurists argue that TV will survive and evolve as a medium by incorporating the Internet to create an enhanced TV viewing experience. Advocates of the potentially democratizing influence of the Internet will probably be disappointed to find they are swimming upstream as far as the human limits of media information entertainment flow is concerned. The more interesting question may be whether ‘functionally equivalent’ or nonequivalent activities will be those that will be replaced if the Internet continues its present growth trends.

Bibliography:

- Blumler J G, Katz E (eds.) 1974 The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspecti es on Gratifications Research. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Budd R W, MacLean M S, Barnes A M 1966 Regularities in the diffusion of two news events. Journalism Quarterly 43: 221–30

- Chaffee S H 1975 The diffusion of political information. In: Chaffee S H (ed.) Political Communication. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, pp. 85–128

- Davis D, Robinson J 1989 News flow and democratic society in an age of electronic media. In: Comstock G (ed.) Public Communication and Beha ior. Academic Press, New York, Vol. 2, pp. 60–102

- Gaziano C 1997 Forecast 2000: Widening knowledge gaps. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 74(2): 237–64

- Kraus S, Davis D, Lang G E, Lang K 1975 Critical events analysis. In: Chaffee S H (ed.) Political Communication. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, pp. 195–216

- Lang K, Lang G E 1983 The Battle For Public Opinion: The President, the Press, and the Polls During Watergate. Columbia University Press, New York

- Lazersfeld P F, Merton R K 1948 Mass communication, popular taste and organized action. In: Bryson L (ed.) The Communication of Ideas. Harper and Bros, New York, pp. 95–118

- Putnam R D 2000 Bowling Alone. Simon and Schuster, New York

- Reagan J 1996 The ‘repertoire’ of information sources. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 40: 112–21

- Robinson J, Godbey G 1999 Time for Life. Penn State Press, State College, PA

- Robinson J, Levy M 1986 The Main Source: Learning from Tele ision News. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Rubin A M 1994 Media uses and effects: a uses-and-gratifications perspective. In: Bryant J, Zillmann D (eds.) Media Effects: Ad ances in Theory and Research. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 417–36

- Weiss W 1969 Effects of the mass media on communications. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E (eds.) 1968–69 The Handbook of Social Psychology,Vol.5,2ndedn.Addison-Wesley,Reading,MA,pp. 77–195

- Wober J M 1989 The U.K.: The constancy of audience behavior. In: Becker L B, Schoenbach K (eds.) Audience Responses to Media Di ersification. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 91–108

- Wright C R 1974 Functional analysis and mass communication revisited. In: Blumler J G, Katz E (eds.) The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspecti es on Gratifications Research. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, pp. 197–212