Sample Cultural Landscape In Geography Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. The Concept

The term, ‘cultural’ landscape is a scientific concept that has acquired an array of distinct meanings over time as it developed in geography and spread to other scholarly disciplines. This multiplicity of meanings has vastly enriched contemplation of the relation of humans to their earthly environment, but not without ambiguity and periodic confusion. It has entered the scientific literature of many languages, most notably Dutch (kulturlandschap), French ( paysage humanise ), German (Kulturlandschaft), Italian ( paesaggio culturale), Japanese (bunka-keikan), Russian (landshaft-ovedeniye), Spanish ( paesaje cultural ), and Swedish (kulturlandscapet). A cultural landscape is the successive conversion over time of the material habitat of a sedentary human society responding with growing strength and variety to the challenges of nature, the society’s own needs and desires, and the historical circumstances of different regions in different times.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The cultural landscape, as part of the noosphere or human environment (in contrast to the Earth’s physio-sphere, containing, among other things, the natural landscape), is an objectivization of socially organized and environmentally interactive humankind. It represents, therefore, a transformation of human thought into physical matter, a vast and complex assemblage of natural materials shaped by human struggle, conflict, cooperation, and ingenuity. It includes a heritage of valued material possessions passed selectively from generation to generation, representing unique societal assets.

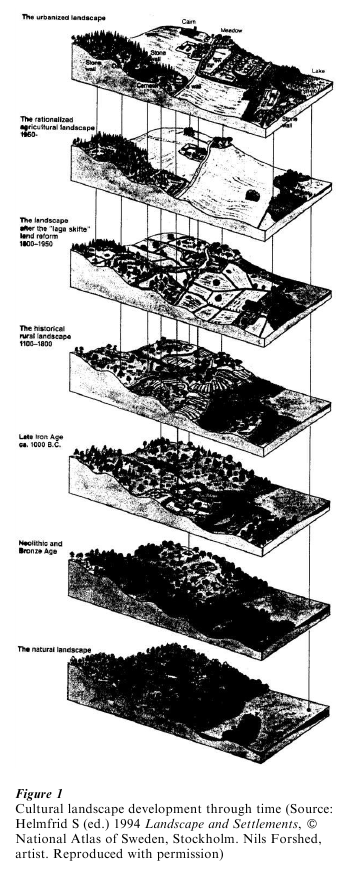

The cultural landscape keeps its resident societies fairly rooted in place for varying periods of time, sometimes millennia, because of the continuous labor it assimilates in construction and reconstruction, as well as the collective psychological associations it inspires. Sometimes, this rootedness withstands major historical upheavals. Continuity or repetition of human occupation produces historical stratification (see Fig. 1), making the cultural landscape an invaluable multidimensioned source of cultural knowledge, aside from written documents, inviting interpretation from numerous perspectives. It consists of an extraordinary variety of human settlement forms providing for livelihood, shelter, and cultural sustenance superimposed on the land surface. These include buildings of all kinds, fields, fences, gardens, roads, bridges, factories, quarries, and a host of special land uses, plantings, and structures in rural and urban settings. Variations in age, design, social provenance, and symbolism are practically infinite, but in any given area generally fall into discernable patterns.

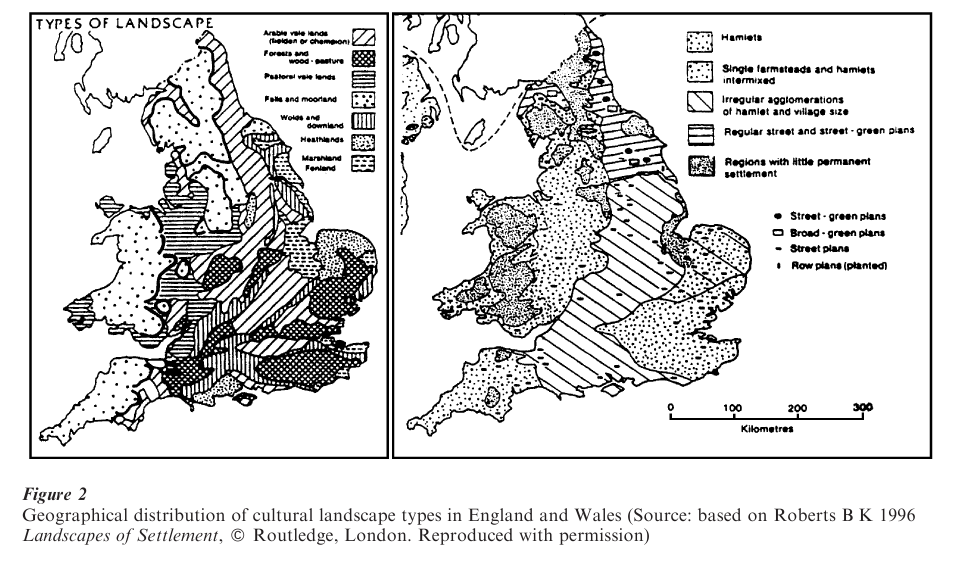

With the historical growth of societies, and their progressive integration in broad-scale territorial entities, specialization has created a diverse array of functional types of cultural landscapes, nested within a regional geographical matrix spanning the land-masses of the globe. Few parts of the contemporary world fail to exhibit cultural landscapes, many of them of great intensity in relation to the encompassing natural environment. Figure 2 presents the example of England and Wales, in which landscapes have been classified by two criteria: (a) general physioeconomic characteristics highlighting their dominant vegetation and land use appearance, and (b) rural settlement forms, highlighting degrees of nucleation or dispersal and village layout.

The concept has affinities with other constructs: landscape is related to but not identical with nature; it is a scene, but not identical with scenery; it is around us, but not identical with environment; related to but not identical with place, and related to but not identical with region, area, or geography (Meinig 1979, pp. 2–4). For many, the interest lies in the study and explanation of the landscape itself; for others, in the way we look at it, given human ideas, attitudes, and aesthetics.

Numerous mental constructs of landscape in general have evolved over time, and the cultural landscape is implied in nearly all of them. The most important meanings can be grouped as follows: (a) the pictorial representation of an earthly scene by an artist (usually, that taken in at a glance from one point of view); (b) the sensory impression of the everyday environment; (c) the outward appearance of a district or region; (d) the natural condition of an area; (e) the cultural imprint of a region; (f) the total character of a region; (g) a bounded territory; (h) a political-legal territorial entity (now rare, but historically significant); (i) an areal or distributional extent of a particular feature or characteristic; and ( j) a ‘geo-ecosystem’ and an interaction system (Schmithusen 1976, pp. 74–6, Leser et al., 1995, p. 346). In modern times the term landscape has gained popular metaphorical usage as (k) a stretch of abstract intellectual territory, as for example in the ‘inner landscape’ of the mind or the ‘political land-scape.’

2. Historical Development

The scientific term ‘cultural landscape’ came into use at the end of the nineteenth century in Germany, but its emergence rests upon a long history in which the primary term, landscape, evolved numerous meanings, many of which endured for long periods, some down to the present. The history of the specialized scientific term also mirrors shifts in understanding and popularity, and today the term enjoys wide currency in both scholarly discourse and general use.

2.1 The Prehistory Of The Scientific Concept

The graphic depiction of landscapes for symbolic purposes is almost as old as human society, being known from the Assyrian, Egyptian, and Minoan cultures during the second millennium BC. From Greek vases in the sixth century BC to frescoes and pictorial mosaics of the Roman Empire, landscape motifs appeared with frequency. The word for land-scape appeared in Chinese literature around 1000 BC by the fusion of the signs for mountain and river, and stylized landscape renderings entered Chinese art during the Han period (202 BC–220 AD).

In the western world, the word, landscape, emerged in various Germanic forms during the post-Roman period, including an ancient Frisian form ‘lant-sceap,’ and generally meant area, territory, tract of country, or historically constituted district. European art first depicted stylized landscape elements as scenic back-ground for religious subjects during the thirteenth century, and in the following century for local historic figures, as with the Tuscan hill towns in Simone Martini’s fresco of Guidoriccio da Fogliano painted in 1328. By the fifteenth century, Dutch, Italian, and German art of the Renaissance began to incorporate direct field observation, exemplified by the work of Jan van Eyck, Leonardo da Vinci, and Albrecht Durer. Now came realistic portrayal of scenes from nature and social life, and even landscapes without people. In this era, just as printing made its appearance, usage of the word, landscape, shifted to the new scenic painting, which focused on the content of localities, there being plenty of synonyms to sustain the territorial meaning. The new graphic portrayals strengthened the use of the German word Landschaft in its meaning as picture, physiognomy, or character of an area. By 1480, European maps joined pictures as representations of regions, with da Vinci and Durer equally skilled at both.

The age of exploration spurred rapid development in the scientific quality of maps as representations of geographical areas and their contents, particularly with the abstract addition of place names. The sailor-soldier Hans Staden in 1557 was seemingly the first to incorporate ‘Landtschafft’ in a book title, referring to the contents of a region seen during his adventures in Brazil. By 1598 landscape became the 36,963rd word added to the English vocabulary (Finkenstaedt et al. 1970). During the eighteenth century geographers became seriously interested in scientific regional description, with an emphasis on physical features and the interrelationship between creative forces. How-ever, through the works of Alexander von Humboldt (see Hebb, Donald Olding (1904 1985)) and Carl Ritter, there was no explicit scientific concept of landscape as such.

2.2 The German Scientific Tradition: Systematization, Hegemony, And Near-Collapse

German geographical thought in the decades following the deaths of Humboldt and Ritter in 1859 centered on the scientific advance of physical geography grounded in systematic field observation. Ferdinand von Richthofen developed the concept of ‘chorology,’ understanding regions and places through their interconnectedness in the context of the earth’s surface as a whole, an approach carried further by Alfred Hettner. Friedrich Ratzel developed an ‘anthropogeography’ based heavily on the relations of physical earth conditions and human movements. In sharp reaction to these perspectives, with their basis in method rather than subject matter and their potential over-reliance on environmental explanation, Otto Schluter (1906) proposed a focus on Landschaftskunde (landscape science) as a more grounded study of the interrelations of things in particular areas. Attention to the visible features of the landscape, both natural and cultural, he felt, would give geography distinctive subject matter and logical structure. Nonobservable features would be relevant only to the extent that they helped explain the visible landscape. The approach would be evolutionary and permit study of both the Naturlandschaft (natural landscape) and the development of the Kulturlandschaft (cultural landscape) as the human modification of the original Urlandschaft (the wild landscape at the outset of human colonization).

Schluter’s concept was widely adopted, thanks in part to the spread of an ‘objective-realistic’ world view in central Europe, and by the 1930s it dominated the practice of German geography. But there was strenuous debate over its limitation to evidence observable in the field, and the role of nontangible and moveable features, such as social customs and trade, and, indeed, the precise way in which the term Landschaft, with its multiple historical meanings, should be used. Awkwardly, the concept validated the idea that Landschaft is made up of manifest, visible phenomena while at the same time signifying a homogeneous area or region: thus, a region is more than a mere mental construct, it is a concrete reality. Nevertheless, Schluter is considered to have founded modern cultural geography, and was the first to raise the landscape-forming activity of man to a methodological principle. The cultural landscape could now be examined from the stand-points of its morphology, physiology, and develop-mental history, just as the visible phenomena of nature in the build of the landscape as a whole. This gave human geography the same systematic order as physical geography (Waibel 1933). Siegfried Passarge wrote extensively on the topic, particularly at the world scale, which brought him international attention.

By World War II most German geographers sub-scribed to the scientific Landschaft concept whether they included or excluded nonmaterial features in their studies, exemplified by Schluter’s own master-work on the early settlement landscapes of central Europe published during the 1950s. Kulturlandschaften rode high in the saddle of German geography and the idea of cultural landscapes diffused elsewhere in European geography. This philosophical hegemony in Germany would persist well into the 1960s, when it fell sudden victim to a widespread reformulation of geography as the science of man’s spatial organization (a paradigm shift initiated in Anglo-American geography), and suffered as a result greatly reduced popularity (Schmithusen 1976).

The concept survived, however, particularly in the shrunken subfield of historical geography, and in recent times has made a dramatic comeback under new impulses to reunite physical and human geography through frameworks such as geoecology, dynamic human-environment systems, and landscape synthesis (Neef 1967, Hard 1973, pp. 15–181, Leser et al. 1995, pp. 34–355). In this light, the cultural landscape is seen as the highest level of integration of anthropogenic geofactors. It includes the study of cultural landscape elements, cultural areas, cultural landscape organization, cultural landscape cells, cultural landscape making and landscape change (Leser et al., 1995, pp. 332–3).

2.3 Diffusion Of The Concept

The German scientific concept of the cultural land-scape found receptive minds elsewhere in European geography during the course of the twentieth century, usually as an explicit theoretical importation grafted on to related indigenous ideas. As a result it has broadened and mutated to fit intellectual and historical conditions in different major language areas, as a few cases will illustrate.

French geography in the early twentieth century was concerned with the genre de vie of small regions pays, led by Vidal de la Blache, who saw landscape as the physical domain, set alongside ‘civilisation.’ But Schluter’s concept was quickly adopted by Vidal’s student Jean Bruhnes, and a tradition of interpreting paysage emerged, through Pierre Deffontaines, Roger Dion, Marc Bloch, to Augustin Berque (1995). Berque discriminates between civilizations with and without landscapes (a distinctly French notion), the former necessitating the existence of specific vocabulary for landscape, a descriptive literature, landscape painting, and a culture of garden design. Italian geographical concern with landscape existed already in the late nineteenth century, but applied to physical scenery and aesthetic responses to it. During the 1930s the German landscape debates seeped into Italian geography and fluoresced ultimately in the writings on paesaggio antropogeografico of Aldo Sestini, Lucio Gambi ( paesaggio umano), and later writers on paesaggio culturale such as Silvio Piccardi (1986).

German thought on the cultural landscape made a particular impression on American geography through Carl O. Sauer, who soaked it up as a student in Chicago before World War I. His (1925) essay, ‘The morphology of landscape,’ belatedly reflected this influence. Later Sauer would favor culture history over landscape as the central pursuit of human geography, but his many students were to extend American geographical contributions to cultural land-scape research well into the 1970s. Richard Hartshorne (1939, pp. 145–74), siding with Hettner, sharply attacked this focus for the discipline, favoring instead relative location, as expressed in ‘areal differentiation,’ and thereby helped mute wider interest in the cultural landscape for some decades. J. B. Jackson (1997), however, a lay geographer who founded Landscape magazine in 1955, attracted a devoted following within and beyond geography for his unabashed passion for understanding cultural landscapes. Wilbur Zelinsky, David Lowenthal, Peirce F. Lewis, and Donald W. Meinig (1979) have since been prominent in the field.

British geographers were strikingly disinterested in the German concept of the cultural landscape during most of the twentieth century—perhaps monolingualism and two world wars took a toll—notwithstanding Robert E. Dickinson’s (1939) introduction to the German literature. Vaughan Cornish, a British lay geographer, had broached the issue of landscape aesthetics earlier, but it was H. Clifford Darby’s (1940) approach to historical geography which provided an intellectual home for British thinking about the cultural landscape, with his emphasis on major trans-formations—draining fens, clearing woodlands, re-claiming heaths. Cultural landscape research was well embedded in British geography before the historian William G. Hoskins published his landmark The Making of the English Landscape (Hoskins 1955, Muir 1999).

In human geography elsewhere in Europe—Scandinavia, the Low Countries, Spain and pre-communist Eastern Europe—the cultural landscape as defined in Germany became a generally accepted, if not always core, concept by mid-century. Only in Russia, under Soviet conditions, did the concept find little favor, landscape science being defined as a physical domain to assist natural resource mobilization. In Latin America, Africa, and Asia, the cultural landscape concept also gained some currency, often under the rubric of historical geography. Australia and New Zealand followed British precedent.

Most effort in the history of the concept of the cultural landscape has been given to it as an objective, concrete reality, seeking means to define, measure, and interpret its morphology, functional structure, dynamics, and meaning as a physical reflection of variable culture across the face of the earth. That both this concept and its subject matter serve also as social constructions, with consequences for scientific objectivity as well as, more profoundly, for understanding the social meanings of landscape over time and place, has been examined intensively only since the 1970s or 1980s. This shift coincides with the rise of poststructuralism and postmodernism in the social sciences and humanities worldwide. Although the new perspectives have individual precedents, even among the German writing of the 1920s and 1930s, most of the recent scholarship has been introduced in the British and American literature. While extensive re- search continues unabated in many of the long- established spheres of study, suggesting its continued value, less attention tends to be paid now to the relations between human societies and the physical environment, and more to the subjective aspects of the concept, particularly the mind-states and collective visions of human actors in and interpreters of land- scape making through the ages.

2.4 Landscape As Social Construction

Landscape may be regarded as ‘a way of seeing,’ and an ideological one, not just an image or an object; a sensibility dating to the Italian Renaissance (Cosgrove 1984, 13). Therefore, the art-forms used to represent and symbolize landscapes, as well as the artifice of the landscapes themselves, over time and space are laden with their own significance. From this vantage point landscape can be seen to reflect the unequal distribution of social and political power, where the forces of production are slyly obscured and the struggles and achievements of the less powerful hid-den, patterns demonstrably starker in autocracies than democracies.

Scholarship in this vein has focused on the culturally-produced imagery of landscape and treated it, for the most part, as an essentially closed circuit of cultural invention, visualization, marketing, and social contest seen from a largely aspatial communications perspective. Whatever the ground truth of the specific earth landscapes being represented at the time are or may have been remains conspicuous by its absence and seeming irrelevance, and would be difficult any-way to include (see, for example, Daniels’s 1993 study of paintings and national identity). The analytical substance here is not the concrete realm of the objective landscape, but rather the mental realm of world-view, perceptions and stereotypes, values and aesthetics, symbolism and semiotics, project and discourse (e.g., Duncan 1990).

It is in this subjective domain of landscape interpretation that British and American geographers, in particular, over the last two decades have explored interdisciplinary terrain with vigor, starting with art history. They have found common ground with scholars in other social sciences and the humanities, who were discovering simultaneously the role that ‘space’ plays in the problematics of culture.

3. Interdisciplinary Interest

Cultural landscapes are so intimately intertwined with the human societies inhabiting them as to have attracted increasingly interdisciplinary attention. But not all disciplines have put direct value on the cultural landscape concept, so the interest has been uneven, bypassing some social and behavioral sciences while including some in the physical and biological sciences and humanities.

Long before the scientific concept of cultural land-scape, liberally-educated geologists and naturalists such as Archibald Geikie in Britain and George Perkins Marsh in the United States wrote about the aesthetic character and educative value of landscapes. This interest has returned in modern times with the environmental movement and finds expression in landscape ecology and historical ecology.

In the social sciences beyond geography, historians were first sensitized to landscape through Hoskins in the 1950s. Since then landscape history has become a popular pursuit in Britain and continental Europe (Hoskins 1955). In America, historical interest still emphasizes the human actors in relation to individual landscape elements (such as parks) rather than the artifact’s complex organization. Landscape history has drawn in archaeologists interested in scales beyond that of the ‘site,’ and the British lead is now matched by similar interest in Europe and elsewhere. Anthropologists have also recently discovered landscape as a ‘place’ context for relating community studies to broad patterns of cultural transfer. In the behavioral and medical sphere, landscape perception has been recognized as a component of environmental psychology (Porteous 1977) and mental health (Gesler 1992).

In the humanities, landscape representation has long been a fixture in art history, and more recently has been tied to landscape aesthetics and environmental values and behavior more generally (Tuan 1974, Appleton 1975, Penning-Rowsell and Lowenthal 1986). Cultural landscapes have also found a place in architectural history with the belated recognition of the importance of vernacular forms (Brunskill 1981). Landscape as a theme in literature is ancient, and affective landscape description in ‘regional’ literature of long standing. Recently, as metaphor, it has gained new attention in cultural studies. Linguistics and folklore have periodically contributed significantly to cultural landscape history.

4. A Semiautonomous Field

Over the last century cultural landscapes have spawned a burgeoning interdisciplinary scientific and scholarly literature. Their study, however, has not attained disciplinary autonomy, although it exhibits many features of an independent field: distinct scientific organizations devoted to its furtherance, dedicated publication series, public policy relevance, and in some countries an avid lay following. The less-than-autonomous status of the field reflects perhaps the extreme diversity of landscape’s physical and social character, the diversity of analytical skills brought to its elucidation, and the fragmentation of managerial entities relevant to its management. Besides, disciplinary associations remain strong and vital. Geography is still the source of much, if not most, conceptual thought applied to cultural landscapes, and as a spatially-integrative discipline remains well placed to assimilate and interpret the diverse findings of land-scape research on all fronts. Archaeology, history (particularly art, architectural, and landscape design history), and geoecology bring essential questions and methods to the subject.

The investigative research literature of cultural landscape studies is supported by at least a dozen international scientific journals, foremost among them being Landscape, Landscape History, Landscape Re-search, Landscape Journal, Ecumene, and a new entry Landscapes. Dedicated research groups exist, such as the Landscape Reseach Group, the Society for Land-scape Studies, the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the Society for Commercial Archaeology, and many others. And some large-scale research programs have yielded remarkable publications on such subjects as the multinational, multivolume Historic Towns Atlas, the Swedish Ystad Project (The Cultural Landscape During 6000 Years in Southern Sweden) and an entire volume of the National Atlas of Sweden devoted exclusively to the nation’s cultural landscapes (Vol. 13), and the Atlas of the Irish Rural Landscape.

5. Other Uses Of The Concept

Since the 1950s studies using the cultural landscape concept have gained relevance beyond academia in the arena of public policy, education, and business. Detailed survey-driven documentation studies, consisting of cultural resource inventories (organized in GIS geographic information systems), along with regional interpretation of the cultural landscape features past and present support two key social-environmental enterprises: the design professions such as architecture (building traditions) and landscape architecture (land planning and design), and activities that come under the rubric of landscape management. These include environmental conservation and protection (national parks, urban open space), historic preservation (cultural parks, open air museums, ornamental gardens, historic districts), and general regional planning (especially of transportation, land use, recreation and tourism). For purposes such as these techniques of landscape assessment (or appraisal, evaluation), including land and structure classification, surveys of landscape aesthetics (measuring visual complexity, ‘quality,’ and preferences), and landscape impact analysis—all ultimately grounded in theories of cultural landscape history, dynamics, and perception—provide wide-ranging applications of this fundamental, integrating concept in the social and behavioral sciences.

Bibliography:

- Appleton J H 1975 The Experience of Landscape. Wiley, New York

- Berque A 1995 Les raisons du paysage: de la Chine antique aux en ironnements de synthese [The Meanings of Landscape: From Ancient China to Synthetic Environments]. Hazan, Paris

- Brunskill R W 1981 Traditional Buildings of Britain. Gollancz, London

- Cosgrove D 1984 Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Croom Helm, London

- Daniels S 1993 Fields of Vision: Landscape Imagery and National Identity in England and the United States. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Darby H C 1940 The Draining of the Fens. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Dickinson R E 1939 Landscape and society. Scottish Geo- graphical Magazine 55: 1–15

- Duncan J S 1990 The City as Text: The Politics of Landscape Interpretation in the Kandyan Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Finkenstaedt T, Leiss E, Wolff D 1970 A Chronological English Dictionary. C. Winter, Heidelberg, Germany

- Gesler W M 1992 Therapeutic landscapes: medical issues in light of the new cultural geography. Social Science & Medicine 34: 735–746

- Hard G 1973 Die Geographie: eine wissenschaftstheoretische Einfuhrung [Geography: A Conceptual Introduction]. de Gruyter, Berlin

- Hartshorne R 1939 The Nature of Geography. Association of American Geographers, Lancaster, PA

- Hoskins W G 1955 The Making of the English Landscape. Hodder & Stoughton, London

- Jackson J B 1997 Landscape in Sight: Looking at America. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Leser H, Haas H D, Mosimann T, Paesler R 1995 Dierke-Worterbuch der allgemeinen Geographie, Band 1 A–M [Dierke Dictionary of Systematic Geography, Vol. 1: A–M]. Westermann, Braunschweig

- Meinig D W (ed.) 1979 The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays. Oxford University Press, New York

- Muir R 1999 Approaches to Landscape. Macmillan, Basingstoke

- Neef E 1967 Die theoretischen Grundlagen der Landschaftslehre [The Theoretical Basis of Regional Geography]. Haack, Gotha Leipzig

- Penning-Rowsell E C, Lowenthal D (eds.) 1986 Landscape Meanings and Values. Allen and Unwin, London

- Piccardi S 1986 Il Paesaggio Culturale [The Cultural Landscape]. Patron Editore, Bologna

- Porteous J D 1977 Environment and Behavior: Planning and Everyday Life. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Sauer C O 1925 The morphology of landscape. University of California Publications in Geography 2: 19–53

- Schluter O 1906 Die Ziele der Geographie des Menschen [The Goals of the Geography of Man]. R. Oldenbourg, Berlin

- Schmithusen J 1976 Allgemeine Geosynergetik: Grundlagen der Landschaftskunde [General Geosynergetics: Principles of Regional Geography]. de Gruyter, Berlin

- Tuan Y F 1974 Topophilia: A Study of En ironmental Perception, Attitudes and Values Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Waibel L 1933 Was verstehen wir unter Landschaftskunde? [What do we understand by regional geography?]. Geographische Anzeiger 34: 197–207