Sample Poverty and Gender in Affluent Nations Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Women are more likely to be poor than men in nearly all Western nations, with the greatest disparity found in the USA. The underlying causes for women’s poverty vary across nations but generally fall into one of three main categories—demographic composition, economic conditions, and government policy. In this research paper, poverty is defined, and the advantages and disadvantages of different poverty measures are noted. Then, the recent scholarship on gender and poverty is briefly reviewed, and women’s poverty rates in various Western, industrialized countries are compared. Finally, the three primary causes of women’s poverty are discussed.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Definitions Of Poverty

The concept of ‘poverty’ is relatively new, having only entered the public lexicon in the latter half of the twentieth century. Poverty can be defined in either absolute or relative terms. It is typically measured with respect to families—not individuals—and is adjusted for the number of persons in a family (because larger families are assumed to need more income but also to benefit from economies of scale). Absolute measures of poverty (typically used in Anglo countries such as the USA and the UK) define poverty in relation to the amount of money necessary to meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. Relative poverty measures (typically used in European countries and by academic researchers) define poverty in relation to the economic status of other members of the society. One half of the median family income is often chosen as the poverty threshold. Absolute and relative measures of poverty reflect divergent ideas about the meaning of poverty—whether it represents the inability to afford basic necessities, or comparative economic disadvantage—and both have advantages and disadvantages. The advantage of an absolute poverty measure is that it clearly indicates whether or not a family’s income is sufficient to sustain a minimal level of subsistence.

However, if an absolute threshold is adjusted only for inflation, during periods of economic growth that same threshold will increasingly reflect a greater level of relative destitution. Relative measures avoid this problem because they are linked to the average standard of living: when median income goes up, the poverty threshold goes up. Yet, because of this practice, ‘poverty’ in one country may imply a vastly different economic status than ‘poverty’ in another country. Relative measures are particularly affected by the income distribution: in countries with a more unequal distribution, poverty rates will be high; in countries with a more equal distribution, they will be low—regardless of the actual standard of living that ‘poverty’ represents.

2. Women’s Poverty In Comparative Perspective

The salience of gender for understanding poverty was first noted by Diana Pearce (1978) who coined the term ‘the feminization of poverty.’ Pearce observed that women and children living in female-headed families were over-represented among the poor, and that the proportion of adults in poverty who were women had been increasing. Since that time, various scholars have used data to examine trends in men’s and women’s poverty rates—and the ratio between them—in order to explore how economic status may be affected by gender (see, for example, McLanahan et al. 1989, Casper et al. 1994). Feminist scholars have raised important issues about the gendered nature of welfare state policies (Folbre 1984, Gordon 1990, 1994, Orloff 1993, O’Connor et al. 1999) and the inequitable distribution of the costs of children (Folbre 1994a, 1994b).

Because poverty is measured at the family level, for married couples, poverty is by definition the same for women as for men: if a married-couple family is classified as poor, the husband, wife, and any children are all considered to be poor. Only for single individuals (defined by most researchers as neither married nor cohabiting) can the rates of poverty differ by gender. Thus, differences in the proportion of the population that is single, and differences in the poverty rates of single men and single women, underlie the overall gender differences in poverty both within and across nations.

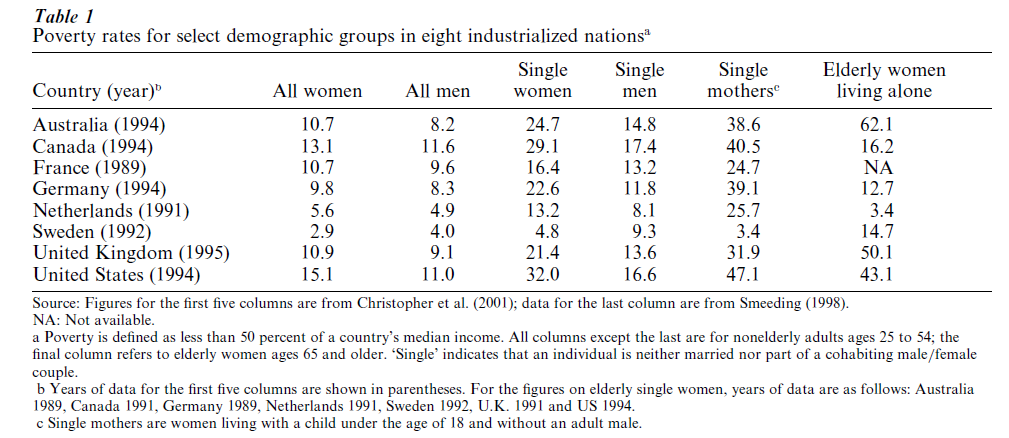

Table 1 presents poverty rates in eight Western, industrialized nations. A relative measure of poverty is used, and an individual is counted as poor if he or she lives in a household with disposable money income that is less than half the median for households in the nation, adjusted for size. The table presents poverty rates for all women and men, for single women and men, and for two groups of single women that are particularly disadvantaged—single mothers and elderly women living alone.

Overall, the table highlights three fundamental observations about gender and poverty in highly industrialized nations. First, within each of the demo-graphic groups shown, poverty levels vary across the nations observed. For example, Sweden has very low poverty rates for most categories, while the USA has notably higher poverty rates. Second, in all but one country shown, women are more likely to be poor than men; the exception is Sweden, where men are slightly more likely to be poor than women. In the USA, the gap between women’s and men’s poverty rates is the highest—about four percentage points. As would be expected—since the single population drives the gender differences in poverty—the gender gap in poverty rates is larger for single individuals than for the adult population overall. Again, Sweden runs counter to the trend, with a lower poverty rate for single women than for single men. For all other countries, the difference in poverty rates between single men and women ranges from about three percentage points in France to more than 15 percentage points in the USA.

The third observation is that among single women, single mothers and elderly women living alone are two groups that face particular economic disadvantage. For single mothers, poverty rates are 25 percent or higher for all countries shown except Sweden; in Australia, Canada, and Germany, about 40 percent of single mothers are poor; and in the USA, nearly half of all single mothers live in poverty. For elderly women living alone, poverty rates range from 3 percent in The Netherlands to 62 percent in Australia, with rates of more than 40 percent observed in both the USA and the UK.

3. Why Are Women Poor?

There is no single explanation for why women are poor—and why they have higher poverty rates than men—particularly as one looks across countries that have vastly different histories, cultures, and social and economic contexts. Three primary factors have emerged, and each will be discussed in turn.

3.1 Demographic Composition

Since differences in poverty rates by gender are fundamentally determined by the size and characteristics of the population that is single (neither married nor cohabiting), the demographic distribution in various countries has an important effect on women’s poverty rates. Several major demographic trends have led to an increasing proportion of adult women (many of whom have children) living separately from men. First, differential mortality rates by gender imply that women live longer than men, and women are, thus, more likely to live alone in their later years. Since single elderly women have higher poverty rates than either men living alone or women living with a spouse (Smeeding 1997), in countries with a greater proportion of elderly women living alone, poverty rates for women will be higher. Yet, mortality rates among Western, industrialized nations are not highly variant; therefore, poverty among elderly women living alone has only a modest impact on overall gender differences in poverty compared to the second major demographic factor, the rise in singleparent families.

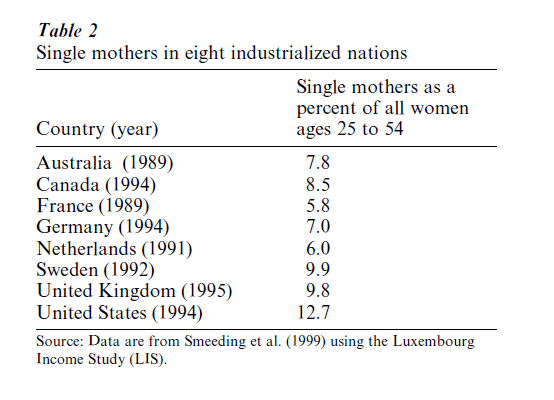

Increases in divorce and nonmarital childbearing have led to notable growth in the number of singlemother families. Although the extent of single parenthood varies across countries, the trend has been remarkably similar—single parenthood has increased in nearly all Western, industrialized nations since the 1960s (McLanahan and Casper 1995). Table 2 shows single mothers as a percentage of all women ages 25 to 54 for eight industrialized nations. Of the countries shown, the proportion of single mothers ranges from 5.8 percent in France to 12.7 percent in the USA (Smeeding et al. 1999).

If the economic costs of rearing children were evenly distributed between mothers and fathers, then even if the parents were not married, the sex–poverty ratio would not be affected. However, in reality, single parenthood has a much greater affect on women’s poverty rates than men’s (McLanahan and Kelly 1999). Women are more likely to have custody of a child following divorce or nonmarital childbirth, and many fathers who live away from their children do not provide adequate financial support for them. Having co-resident children decreases a household’s economic status by definition, because children require economic resources but do not contribute any additional income. Unless the government provides generous financial support when the noncustodial father fails to pay (as is the case in Sweden), in countries with a high proportion of single mothers, poverty rates for women will be high. For this reason, the prevalence of single motherhood represents the major demographic factor underlying the gender disparity in poverty rates.

3.2 Economic Conditions

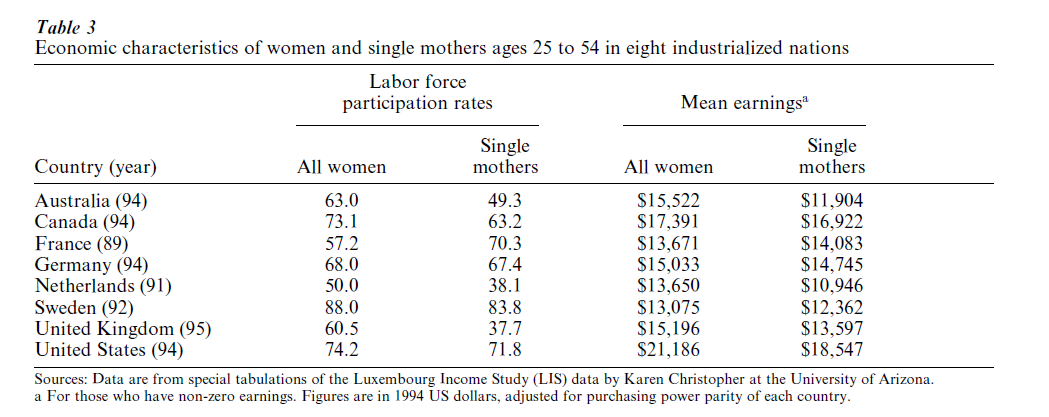

The rise in female labor force participation, especially among married women with children, represents one of the most dramatic socioeconomic changes in the West in the latter half of the twentieth century. Table 3 shows that labor force participation rates for all women (in eight countries) range from 50 percent in The Netherlands to 88 percent in Sweden; employment rates for single mothers vary between 38 percent in The Netherlands to 84 percent in Sweden. While women are increasingly entering the labor force, their employment rates remain lower than those of men. Further, women have average earnings that are significantly lower than those of men. As shown in Table 3, women’s average earnings (among those who have any earnings) range from approximately $13,000 in Sweden to about $21,000 in the USA; earnings for single mothers vary between about $11,000 in The Netherlands to $18,500 in the USA.

Because, relative to men, women have less income from earnings to support themselves and their children, women are more likely to be poor. (This, however, is not a factor affecting elderly women’s poverty as the elderly are no longer of working age.) Yet, earnings per se are not the only reason why women have higher poverty rates. Rather, the fact that women disproportionately bear the responsibility of rearing children has important indirect effects on their economic status. In particular, caring for children limits the amount of time that women are able to work (as well as the energy they may have available to invest in their work), and it also increases the costs of working because women must pay for out-of-home child care (not counted in the poverty measure). In addition, women who reduce their work hours or leave the labor force in order to care for children lose vital work experience which affects both their earnings and their seniority in the workplace.

3.3 Government Policy

All individuals and families receive income from two primary sources—the market and the state—in addition to any private transfers they may receive. Government policy has a significant effect on women’s economic well-being because it can either obviate or intensify the inequalities that result from the operation of the market economy. Among single individuals living without children, government policy has little impact on women’s poverty because men and women are largely treated the same. Although there may be some differences between elderly men and women in how pensions are allocated in various countries, differences in government policies primarily affect the economic status of single mothers and their children.

Welfare states vary dramatically in the extent to which they ‘socialize’ the costs of children. Feminist scholars have noted that many members of society benefit from children being brought up well (Folbre 1994a, 1994b), and yet market mechanisms fail to equitably apportion costs for this ‘public good’ (Christopher et al. 2001). In countries where more of the costs of childrearing are borne by governments instead of parents, women’s poverty rates tend to be lower. In general, single mothers tend to benefit if a greater proportion of welfare assistance is universal rather than means-tested, because they are not faced with high marginal tax rates on their earnings that result from decreased welfare benefits. The overall level of income assistance provided to single mothers varies notably across industrialized nations; mean transfers for single mothers as a percentage of median equivalent income range from 22 percent in the USA to 71 percent in The Netherlands (unpublished tabulations of Luxembourg Income Study data by Timothy Smeeding and Lee Rainwater).

Numerous scholars have developed typologies that classify welfare states along particular dimensions. Probably the best known is by Esping-Anderson (1990) which classifies welfare states into three categories according to decommodification (the ability of individuals to subsist apart from labor and capital markets) and stratification (differences between classes).

(a) Social democratic states, typified by the Scandinavian countries, promote gender equality and provide the most generous support to single-parent families. These nations emphasize full employment, and work and welfare are intricately intertwined, with some part-time public jobs provided for mothers. Many benefits and allowances are universal, supplemented by specific programs targeted to needy families. Women’s employment is encouraged by the provision of high-quality childcare services and extensive parental leave. Also, the government guarantees that support is provided to children who do not live with both parents. Because of these policies, mothers are able to combine work and parental responsibilities and to ‘package’ income from both market and government sources.

(b) Conservative-corporatist nations also have generous transfer systems, but they are more traditional with respect to family values and expectations (largely due to the significant influence of the Church). Benefits are generally targeted toward families (rather than individuals), and inequalities across families and households may be sustained. An important component of welfare policy is social insurance, which is linked to labor force participation and may differ by occupation. Austria, France, Germany, and Italy are representative conservative-corporatist states.

(c) In the liberal welfare states (notably the Anglo countries), assistance is primarily means-tested with modest universal transfers, primarily paid to the elderly or disabled. Emphasis is on the market and individuals’ labor force activity as the primary means for resource allocation. Benefit levels are typically meager when compared to average wage levels, and recipients are often stigmatized by nonrecipients. Supports for working mothers, including public childcare, are limited, with little or no paid parental leave. Parents who live away from their children are expected to pay child support, although the government does not provide any assistance for children of noncustodial parents who fail to pay. Because welfare benefits are income-tested, women have a difficult time combining work and welfare in order to escape the ‘poverty trap.’

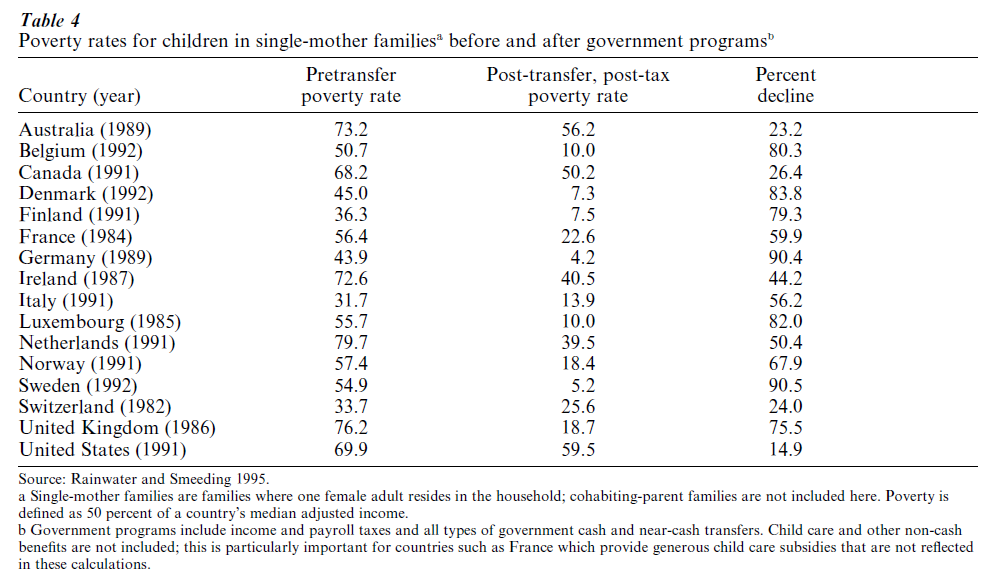

These variations in welfare state policy lead to dramatic differences in the economic status of women and children. Table 4 presents poverty rates for children living in single-mother families both before and after government taxes and transfers are included in income (while childcare and other non-cash benefits are not included). The table shows that, with several exceptions, the percentage decline in the poverty rates roughly clusters according to the three categories of nations in Esping-Anderson’s typology. Government tax and transfer policies reduce the poverty rates in each of the four social democratic nations shown in the table (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) by 68 percent or more. In the corporatist nations, poverty reductions fall in the middle of the spectrum with a 60 percent decline in France and a 56 percent decline in Italy. Germany is an important exception, with its government policies reducing poverty for children in single-mother families by fully 90 percent. The lowest reductions in poverty rates are noted in the liberal states, such as 26 percent for Canada, 23 percent for Australia, and 15 percent for the USA. The UK represents another exception because its policies reduce poverty by 76 percent—a much greater decline than in the other liberal states.

Some feminist scholars have criticized EspingAnderson’s framework because it emphasizes workers’ dependence on employers while ignoring women’s dependence on men. Orloff (1993) argues, for example, that welfare regimes should be judged by the extent to which they allow women to establish independent households. In contrast, other feminist scholars have raised questions about women’s dependence on the welfare state (Gordon 1990, 1994) and gender biases in the welfare state (Nelson 1990).

4. Conclusion

Ultimately, reducing women’s poverty in industrialized countries requires the convergence of all three factors—demography, the market economy, and government policy—to better support women and their children. This is because women’s economic status depends on whatever resources they can conjointly obtain from the family, the market, and the state (Christopher et al. 2001). First, women’s poverty is closely tied to whether the responsibility for children is shared equally between mothers and fathers. Private transfers, regulated by the government, may be just as important as public transfers in compensating for the demographic changes that have resulted in women bearing a disproportionate share of the cost of children. Second, women benefit from market economies that pay men and women equally. Despite the recent gains in wages relative to men, women (especially mothers) earn less than men in all Western countries. Countries that promote gender equity in wages and that maintain high minimum wages reduce the poverty rate of all women, especially single mothers. Third, government policy can be assessed both in terms of the level of support provided to single mothers and the extent to which public support encourages or discourages labor force participation. In particular, childcare subsidies and parental leave policies enable women to balance their responsibilities as parents and workers, which ultimately reduces poverty and increases economic independence.

Bibliography:

- Casper L M, McLanahan S S, Garfinkel I 1994 The genderpoverty gap: what we can learn from other countries. American Sociological Review 59: 594–605

- Christopher K, England P, McLanahan S, Ross K, Smeeding T M 2001 Gender inequality in poverty in affluent nations: the role of single motherhood and the state. In: Vleminckx K, Smeeding T M (eds.) Child Well-Being, Child Poverty and Child Policy in Modern Nations. The Policy Press, Bristol, UK, pp. 199–219

- England P 1997 Gender and access to money: what do trends in earnings and household poverty tell us? 8th International Meeting. Comparative Project on Class Structure and Class Consciousness. Canberra, Australia

- Esping-Anderson G 1990 The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK

- Folbre N 1984 The pauperization of motherhood: patriarchy and public policy in the United States. Review of Radical Political Economics 16(4): 72–88

- Folbre N 1994a Children as public goods. American Economic Review 84: 86–90

- Folbre N 1994b Who Pays for the Kids?: Gender and the Structures of Constraint. Routledge, New York

- Gordon L (ed.) 1990 Women, the State, and Welfare 1890–1935. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI

- Gordon L 1994 Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- McLanahan S, Casper L 1995 Growing diversity and inequality in the American family. In: Farley R (ed.) State of the Union: America in the 1990s, Vol. 2 Social Trends. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 1–45

- McLanahan S S, Kelly E L 1999 The feminization of poverty: past and future. In: Chafetz J (ed.) Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 127–45

- McLanahan S S, Sorenson A, Watson D 1989 Sex differences in poverty, 1950–1980. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 15: 102–22

- Nelson B J 1990 The origins of the two-channel welfare state: workmen’s compensation and mother’s aid. In: Gordon L (ed.) Women, the State, and Welfare. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI

- O’Connor J S, Orloff A S, Shaver S 1999 States, Markets, Families: Gender, Liberalism, and Social Policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain, and the United States. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Orloff A S 1993 Gender and the social rights of citizenship. American Sociological Review 58: 303–28

- Pearce D M 1978 The feminization of poverty: women, work and welfare. Urban and Social Change Review 11: 28–36

- Rainwater L, Smeeding T M 1995 Doing poorly: the real income of American children in a comparative perspective. In: Skolnick J H, Currie E (eds.) Crisis in American Institutions. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, pp. 118–25

- Smeeding T M 1998 Reshuffling responsibilities in old age: the United States in a comparative perspective. In: Gonyca J (ed.) Re-Securing Social Security and Medicare: Understanding Privatization and Risk. Gerontological Society of America, Washington, DC, pp. 24–36

- Smeeding T M, Ross K, England P, Christopher K, McLanahan S S 1999 Poverty and parenthood across modern nations: findings from the Luxembourg Income Study. Luxembourg Income Study, Working Paper No. 194