Sample Labor And Gender In Developing Nations Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The women’s movement has made the world aware of the importance of gender in the world’s labor markets. However, definitions and methods of enumeration still leave out a large section of the female work force. Even where women are included as part of the labor force they face highly segregated labor markets. Since about 1980, globalization and structural adjustment programs have negatively impacted labor movements in developing nations. However, in the process of dealing with change, international trade unions have realized the importance of organizing women workers especially in the areas of agriculture and the informal sector. These are areas of growth of the labor movement for women in the future.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The World’s Labor Force

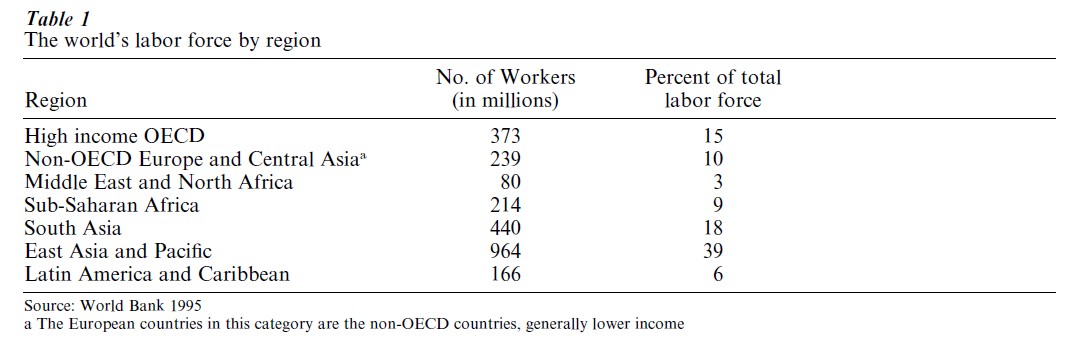

The world’s labor force has been increasing at a fast rate in the recent decades and almost doubled between 1965 and 1995, from 1.3 billion to 2.5 billion (World Bank 1995). As Table 1 below shows, the largest labor force is in the poorest countries.

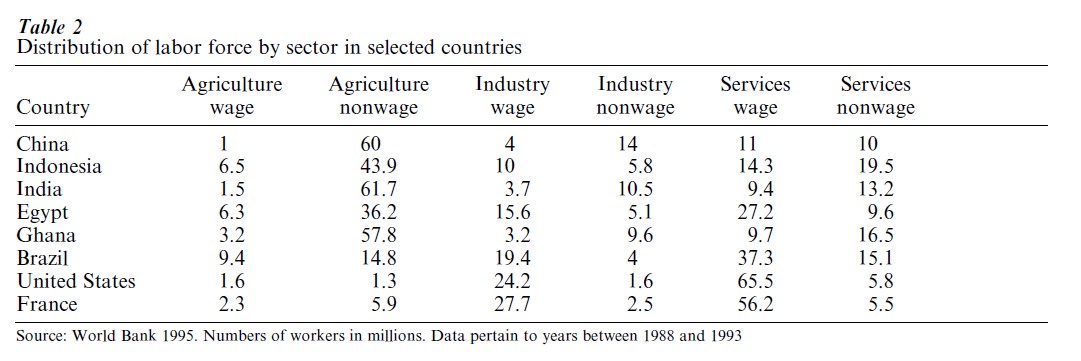

In most parts of the world, most employment is still in the nonwage, mainly agricultural sector. As Table 2 reveals, whereas employment in industrialized countries tends to be in industry or services and workers are earning a wage (USA nearly 90 percent, France 74 percent), the employment in the developing world tends to be in the nonwage sector (China 84 percent, Ghana 85 percent). So, it must be remembered that when we discuss the labor force in the developing world we are talking about a labor force that is either predominantly self-employed, in market or subsistence activities, or works in family nonpaid employment.

2. Women And Work

Women are part of the labor force in every country, but many aspects of the work they do are very different from men. These differences include type of work, place of work, hours of work, and even attitude towards work. Because of these differences, the work done by women is often not recognized as work, and sometimes women are undercounted in official labor force statistics. In the 1990s there was a concerted attempt from women’s organizations and academics to move towards a wider definition of work which would include much of the work that women do.

Women work in fields, in factories, in offices, in mines, on waterways, much as men do, but unlike men, the household is also a major center for economic activity for women. Home-based workers, such as garment workers or leather makers, work within their homes, as do subsistence farmers and animal tenders. Women often undertake unpaid production of goods for the market as part of the family business. In addition, women usually do unpaid household work like cleaning and cooking. Government enumerators and even the women themselves often do not understand that other than unpaid housework, all other types of work should be counted as part of the market economy according to the official definitions of the ‘labor force’ stipulated by governments and international agencies. Because of this wide variety of work, and because of the differing perceptions of what constitutes work, women’s active participation in the economy tends to remain undercounted.

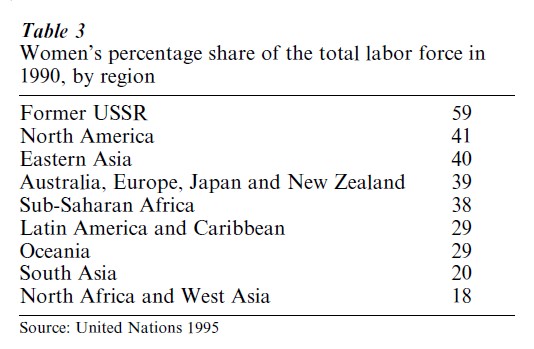

The total number of economically active women in 1990 was estimated to be 828 million. However, women’s share of the labor force, as counted in the population censuses, varies widely from region to region, as Table 3 shows.

Women’s share of the labor force is higher in those countries where the majority of the labor force is in the formal wage sector. In agricultural societies and where the informal sector is a high proportion of the labor force, women’s work tends to be around the household and the family farm and hence undercounted.

It is not easy in a population or household survey to decide whether a person is working or not, and what people are working at, particularly women in developing regions. Terms such as employment, job, work and main activity mean different things to different people. Interviewers also contribute to bias when they assume that women or children are not economically active. Persons who work for a wage or a salary are usually enumerated as economically active regardless of how the questions are phrased. The complications arise as one moves from wage and salary employment to self-employment—especially in the informal sector—and to unpaid labor in a family farm or business: that is from more male-dominated to more female-dominated forms of economic activity. For example, a methodological survey in India found that 13 percent of adult women were wage or salary earners. When market oriented production was included—for example, family business, self-employment, crafts and agricultural activities—the figure rose to 32 percent. When the new ILO (International Labour Organization) standard was fully applied, 88 percent of women were found to be economically active (United Nations 1995).

Even women in the formal wage economy generally are segregated in different occupations from men. A recent cross-national study (Anker 1998) found that occupational segregation by sex is extensive in every country. Approximately one half of the workers in the world are in an occupation where one sex dominates to such an extent that the occupation could be considered a ‘male’ or ‘female’ one (an extent of more than 80 percent). In every country, female occupations generally are seen as less ‘valuable’ with lower pay, lower status, and fewer advancement opportunities. For example, 88 percent of managers, legislative officials, and government administrators are men. Occupations open to women are consistent with stereotypes of women. However, levels of occupational segregation vary across regions with the Asia Pacific region having the lowest level and the Middle East North Africa region, the highest.

3. Globalization

Since the 1970s, there has been dramatic growth of global trade. Markets across countries and regions are becoming increasingly linked, so those workers in even remote rural areas of developing countries are being affected increasingly by the trends in the global product and finance markets. Financial and capital flows also increased as a proportion of GDP. There has been a large increase of capital outflow from industrialized countries since 1980. Among the causes of this growth of trade are reductions in trade barriers through regional or multilateral trade agreements; rapid expansion of foreign direct investment by multinational companies; reduced barriers to international capital transfers, resulting in large flows of equity funds and other speculative investments across national borders; and diffusion of communication facilities that have dramatically increased the speed of transfers.

Since about 1980, globalization, along with structural adjustment programs, brought many changes in the structure of employment and the opportunities available. In many of the developed countries, the unskilled jobs have been transferred to the developing world, concomitant with a rise in opportunities for the skilled and professional workers at home. In Asia there was a rise in employment opportunities, wage levels, and skills, especially for younger women. However, after the 1990s economic crisis in Asia, there has been a major setback for employment. Poverty levels, which had fallen below 20 percent, have risen dramatically, to as much as 60 percent in Indonesia. Latin American countries too, had major upsets with very high inflation rates, high unemployment, and falling well-being. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa were hit the hardest with falling income per capita, high unemployment, and social unrest.

4. Informal Sector

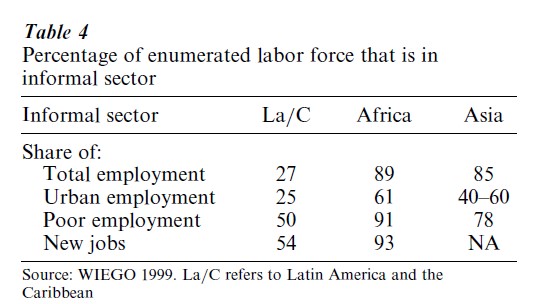

The period of globalization has also seen the growth of the informal sector in all regions of the world. Since the term ‘informal sector’ was coined in the 1970s, it has been defined in various ways and gone in and out of favor in development circles. One dominant school of thought predicted its demise, arguing that as GDP per worker increased, the share of the work force in the formal sector would rise. However, due to slow growth, economic reforms, and/or changing patterns of production, the informal sector has grown steadily in the developing world (and in some countries of the developed world). In the 1980s and 1990s, the share of the work force in the formal sector slowed down or absolutely declined in most developing countries. It was only the rapidly growing economies of East and Southeast Asia that experienced substantial growth of formal sector employment (although the Asian economic crisis of the 1990s led to lay-offs in the formal sector and dramatic growth in the informal sector).

As an umbrella concept for economic activities that fall outside the modern and (in many countries) the agricultural sector, the informal sector has been defined in various ways. Alternative definitions emphasize the fact that informal sector activities rarely comply with official and administrative requirements; are not adequately reflected in official statistics; and are not covered by protective legislation or trade union organization. In an attempt to encompass the heterogeneity and complexity of the informal sector, the 15th International Conference of Labor Force Statisticians in 1993 adopted an international definition of the informal sector to be used in the collection and presentation of labor force data. According to this 1993 international definition, the informal sector comprises (a) informal self-owned enterprises (with only family workers or temporary employees) and (b) informal enterprises with more permanent employees. Under this definition, whether ‘informal’ is restricted to nonagricultural activities, nonregistered activities, and/or enterprises of a given size is left up to individual countries. Whichever defining characteristics are adopted by individual countries, several sets of activities are particularly difficult to capture in national statistical surveys: itinerant or seasonal or temporary jobs (e.g., on construction sites or road works); secondary activities; and street vending. In addition, no matter what defining characteristics are adopted by individual countries, one set of workers is left out of the 1993 definition: subcontract workers or out- workers who work for formal firms. These limitations of official data notwithstanding, the estimated size of the informal sector is quite large, as shown in Table 4.

In India, where the official statistics are relatively good, it is estimated that the informal sector accounts for 90 percent of the total workforce and 63 percent of GDP and the household sector (of which the informal sector is the major share) accounts for 76 percent of savings (WIEGO 1999).

If home-based workers and street vendors (particularly women in these sectors) were more adequately reflected in official statistics, the size and contribution of the informal sector would be larger still. In Latin America and Asia, microstudies suggest that home-based workers (both own account and subcontract workers) account for 40–50 percent of the workforce in key export industries—textiles, garments, and footwear. In West Africa, national surveys suggest that street vendors account for more than 33 percent of the informal urban labor force and more than 30 percent of the total urban labor force.

5. Genesis of Labor Movements

The Labor Movement as we know it today began to emerge in Europe and the United States in the middle of the nineteenth century as a response to the massive industrialization which gave rise to a new class of the ‘proletariat.’ The first trade unions represented skilled male workers, and reflected their origins in earlier craft guilds. These trade unions developed support and welfare provisions (e.g., in times of unemployment) for their members and helped them find employment. Trade unions that developed later in the nineteenth century were more likely to organize all workers in the industry, particularly unskilled and general workers. This later trend was very much associated with general ideas of socialism that were strong at the time and linked to ideas of cooperation as well as trade unionism.

As industrialization came to the developing world there were spontaneous struggles by workers to organize for better work conditions. However, it was only after 1920 that the labor movement developed in the third world, most of whose countries were still under colonial rule. 1920 was momentous for the labor movement for two reasons. First, the International Labor Organisation was set up as a tripartite body with membership of National Trade Unions, Governments, and National Association of Employers, to regulate the conditions of work and provide a forum for dialogue. At the same time the newly formed USSR had followers in communist parties in most countries, who began organizing within the labor movement. The next 50 years saw the consolidation of labor movements in most developing countries along with freedom movements, which led to newly in-dependent countries in most of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Many of the newly independent countries included the Right of Association as a fundamental right in their Constitutions, creating a legal basis for the newly formed trade unions. Labor laws were also passed in most countries to protect the working conditions of the workers. At the same time most countries, influenced by the economic successes of the Soviet Union, instituted central economic planning and large public sector organizations. Trade unions flourished in these. At the national level in many countries, individual trade unions attempted to come together to form national federations. These federations, with their large memberships, became politically powerful in many countries. The mid-twentieth century was the heyday of the labor movement worldwide.

6. International Labor Movements

The labor movement has always recognized the importance of international links and trade unions in particular trades have attempted to organize across countries. For example, the IUF is one of 14 international trade secretariats that unite workers on the basis of their industry, craft, or occupation. Founded in 1920 through the merger of international federations of bakery, brewery, and meat workers, it was first known as the International Union of Food and Drink Workers. Its headquarters were located in Zurich and membership was almost entirely European until World War II. Today the IUF represents 329 organizations in 118 countries, in all regions of the world. These organizations represent approximately 10 million workers. However, it was during the period when the trade union movement was at its height that that the major international trade union federations were formed. The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) was established in 1949, with National Federations of noncommunist trade unions as its members. The World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), based in Moscow, was the international Federation of trade unions with a communist philosophy. In addition there were smaller international federations such as the Christian Labor Federation. Today the ICFTU represents 213 organizations in 143 countries on all five continents, with a membership of 124 million, of whom 43 million are women.

7. Decline Of The Trade Unions

Globalization of the international economy has coincided with the decline of the power of trade unions worldwide. In the industrialized countries, the profile of production began to change. Multinational corporations moved their production into the developing countries. In these affluent nations, self-employment began to increase, employment in manufacturing and blue collar jobs declined, and service sector, professional, and white-collar employment grew. As a result, the proportion of the labor force in trade unions declined.

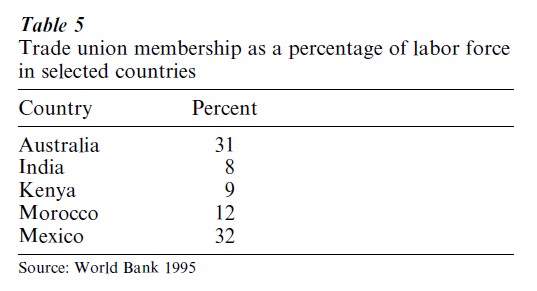

In developing countries, new trends began to be seen. East and South East Asia began developing at a fast pace with growing exports. The governments of these countries more or less suspended democratic functioning and with it the freedom for workers to create and join trade unions of their own choosing. In South Asia, the trade unions had always been confined to the formal sector—the private corporate and public sector enterprises—covering barely 10 percent of the workforce. As globalization and liberalization policies spread, these sectors shrank instead of expanding as had been expected, so this shrank the proportion of the national workforce unionized. In most of Africa (other than South Africa, which has had a unique history of unions being in the forefront of antiapartheid struggles), the small trade unions, which in any case were confined to a small section of industry, were suppressed as antidemocratic forces gained the upper hand. In Latin America, countries with large industrial sectors or with large plantations had sizable unions with militant histories. However, as liberalization and globalization policies spread many of these unions were attacked. In some cases, individual unionists were killed. In the USSR and Eastern Bloc, trade unions were controlled by the State, but in many countries these unions became the vehicles for antigovernment activity leading to a collapse of the USSR and change of regimes in the former socialist countries. Table 5 shows that only a small minority of workers are covered by unions in a number of regions.

The reasons for decline of the labor movements have been both external and internal. One factor has been the globalization of production which led to decline of production in the countries of strong unionization, as well as the casualization of production which led to the closing of unionized factories and work going into small and contract production. A second factor has been the antilabor policies followed by governments in most developing countries. This has been most pronounced in South East Asia, Latin America, and some of the African countries.

The labor movement has been subject to a number of major internal weaknesses. Perhaps the major weakness has been the confining of the movement to large public and private enterprises. In the earlier years of development, it was optimistically believed that the economic structures of developing countries would change to become more like those of industrialized countries, i.e., with most of the workforce in manufacturing or services in the formal sector with a formal employer-employee relationship. However, instead of shrinking the informal sector has in fact expanded, and the difference in earnings, access to social security, and security of work, between the formal and informal, unionized, and nonunionized workers has grown. The labor movement was unable to reach out and/organize the workers of the informal sector and as a result their own influence has continued to shrink.

8. Women And Labor Movements

In the early days of industrialization, when working conditions were bleak and hours were long, women were an important, though generally unskilled part of the industrial work force. However, the first trade unions were meant for skilled workers and based on a principle of exclusivity—protecting the employment of the skilled workers and keeping out unskilled. In practice, this often meant excluding women. This tradition went on until the early twentieth century when, for example, the engineering union would not admit women to their membership, even when they made up a majority of the workforce in a factory. Male union workers also adopted the ideology of the ‘family wage,’ arguing that employers should pay male workers enough that they could support wives and children. Part of this ideology was that the woman belonged in the home and the man was the breadwinner.

The second wave of trade unionism started with the textile industries in England where a majority of workers were women. At the end of the nineteenth century there was a great movement to organize all workers and this is what led to the development of the general unions which organized the ‘unskilled’ and ‘semiskilled,’ including some women. However, even in this period, many women workers were excluded. Most industries and professions excluded married women and the biggest source of employment for women was still domestic service, completely unorganized. As a result of the exclusion of women from some trade unions and the fact that women were in many different forms of informal employment, in addition to trade unions there were strong women’s organizations—the Women’s Trade Union League and Women Workers’ Federations. Some advocated women joining general unions, others favored women having their own unions.

After World War I, unions gradually dropped their ban on women members and the separate women’s organizations declined. However, married women were still not usually allowed to work formally. Moreover, as the trade unions were able to get better wages and working conditions for their members the numbers of women in most unionized industries declined due to a number of reasons. First, the societal belief was that the males in the family should earn while the women were homemakers. Unions demanded a ‘family wage’ so that women could stay home. As wages and working conditions improved, men replaced women in the workforce. Second, protective legislation, such as limiting number of hours worked, night shifts, prohibition of entry into certain jobs, began to limit the scope of work available to women. Finally, new technologies demanded new skills for which men were able to get the training denied to women. Women’s employment in modern and formal industries declined, and with it the participation of women in the trade unions.

The 1970s, however, saw the growth of a powerful world-wide women’s movement. This feminist movement, as it spread to developing countries, brought more skilled and educated women into the labor force. Women’s employment in white-collar work began increasing, and with it women’s consciousness of their own rights. In the 1980s women in the trade unions too began to voice the need for greater representation. Women began to demand more power within the trade unions and in the 1990s the international trade unions as well as trade unions at the national level began to focus on drawing more women as active members of trade unions. The ICFTU, Programme of Action for Integration of Women into Trade Union Organisations was first adopted in 1978, and updated in 1985 and 1988. The 15th World Congress in 1996 adopted resolutions on ‘Equality’ and ‘Women and Development’ calling on ICFTU and its affiliates to integrate gender perspectives into all their work, and to adopt a positive action program for women. The ICFTU reports that women’s share of its affiliates is 34 percent and that women’s membership has been growing in all regions in the 1990s.

However, the majority of women in developing countries are in agriculture and the informal sector. These are areas where the labor movement is still weak, and so they have not yet been integrated into labor movements.

9. The Future Of Women In Labor Movements

Unions in developing countries have begun to recognize the importance of organizing the informal sector. However, these small unions have little or no voice at the national or international level. A number of international movements are now developing that are trying to represent women who work in the informal sector in developing nations. Among these are HomeNet, the international alliance of home-based workers, the International Alliance of Street Vendors, and the World Fisherpeople’s Federation. If these alliances are examples of the future, the new labor movement will be one in which workers of all types, not just ‘employees,’ will be represented, and where the whole concept of work and worker will undergo a change to bring the large majority of informal sector women into the mainstream of the economy.

Bibliography:

- Ackerman F, Goodwin N R, Dougherty L, Gallagher K 1998 The Changing Nature of Work. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Anker R 1998 Gender and Jobs: Sex Segregation of Occupations in the World. International Labor Office, Geneva, Switerland

- Asian Development Bank 1998 Annual Report. Oxford University Press for the African Development Bank, Oxford, UK

- Baksh-Soodeen R 1994 Caribbean feminism in international perspective. Mumbai Economic and Political Weekly, October 29

- Brtiskin L, McDermott P 1993 Women Challenging Unions. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, ON

- Coo A H, Lorwin V R, Daniels A K 1992 The Most Difficult Revolution: Women and Trade Unions. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

- Cunnison S, Stageman J 1995 Feminizing the Unions. Avebury, Aldershot, UK

- Figueirendo J, Shaheed Z 1995 New Approaches to Poverty Analysis and Policy—II. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland

- FNV CNV 1997 Organizing Change: Strategies for Trade Unions to Organise Women Workers in Economic Sectors with Precarious Labour Conditions. Stichting FNV Press, Amsterdam

- Hosmer Martens M, Mitter S 1993 Women in Trade Unions, Organizing the Unorganized. ILO, Geneva, Switzerland

- International Confederation of Free Trade Unions 1970 ICFTU Twenty Years (1949–1969). International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, Brussels, Belgium

- International Confederation of Free Trade Unions 1986 Working Women: ICFTU Policies and Programmes. International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, Brussels, Belgium

- International Labour Office 1995 World Employment. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland International

- Labour Office 1997 World Employment. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland International

- Labour Office 1999 World Employment Report 1998–99. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland

- International Labour Office (FEMMES) 1999 Gender Issues in Labour Market Policies. Unpublished www document.

- Mariam H Y 1994 Ethiopian women in the period of social transformation. Mumbai Economic and Political Weekly, October 29

- Mathur V S 1976 Changing Role of Trade Unions in De eloping Economies. International Confederation of Free Trade Unions Asian Regional Organisation, Green Park

- Ramaswamy E A 1995 Six Essays for Trade Unionists. India Office South, New Delhi, India

- Rodgers G 1995 New Approaches to Poverty Analysis and Policy—I. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland

- Rodgers G, van der Hoeven R 1995 New Approaches to Poverty Analysis and Policy–III. International Labour Office Publications, Geneva, Switzerland

- Shah H, Gothoskar S, Gandhi N, Chhachhi A 1994 Structural adjustment, feminisation of labour force and organisational strategies. Mumbai Economic and Political Weekly October 29

- Thomas H (ed.) 1995 Globalization and Third World Trade Unions: The Challenge of Rapid Economic Change. Zed Books, London

- United Nations 1995 The World’s Women. United Nations, New York

- WIEGO 1999 Report of the First Annual WIEGO Meeting. Ottawa, Canada, April 1999

- Worku Z 1994 Organising women within a national liberation struggle. Mumbai Economic and Political Weekly, October 29

- World Bank 1995 World Development Report: Workers in an Integrating World, World Bank, Washington, DC