Sample Legal Perspectives on Deterrence Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The criminal justice system (CJS) dispenses justice by apprehending, prosecuting, and punishing lawbreakers. These activities also project a threat of punishment. Deterrence occurs when some would-be law breakers conclude that the price of crime is prohibitive. General deterrence refers to the crime prevention impact of the threat of punishment on the public at large. Specific deterrence refers to the impact of punishment on persons actually punished. The actual experience of punishment may alter an individual’s perceptions and opportunities. Also, persons for whom general deterrence has failed may be systematically different than the population at large. For both these reasons specific deterrent effects may be smaller than the subject of this research paper, general deterrent effects.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. A Brief Review Of Research On General Deterrence

Deterrence research has evolved in three distinctive and largely disconnected literatures—interrupted time series, perceptual, and ecological studies (Nagin 1998).

1.1 Interrupted Time Series Studies

Interrupted time series studies examine the impact of targeted policy interventions such as police crackdowns or implementation of statutes changing penalties. The best-designed studies mimic important features of a true experiment—a well-defined treatment regime, measurement of response before and after treatment and a control group. Two classic examples are Ross’ studies of the impact on drunk driving of the British Road Safety Act and of Scandinavian-style drunk driving laws (Ross 1982).

The great proportion of interrupted time series studies have examined the impact of drunk driving laws or of police crackdown, on drug markets, disorderly behavior and drunk driving. A less extensive literature has also examined the impact of gun control laws and ordinances. Excellent reviews of these studies are available from Sherman (1990) and Ross (1982).

Both reviews conclude that interventions are generally successful in generating an initial deterrent effect. One exception may be interventions that increase sentence severity. If judges or juries believe that the penalties are too harsh, they may respond by refusing to convict guilty defendants with the result that the policy increases rather than deters the targeted behavior. Indeed, Ross concludes that efforts to deter drunk driving with harsher penalties commonly fail for precisely this reason. Sherman and Ross are also in agreement that the effect is generally only transitory: the initial deterrent effect typically begins decaying even while the intervention is still in effect. However, in some instances, the decay is not complete even following the end of the crackdown.

1.2 Perceptual Deterrence Studies

1.2.1 Summary Of findings. The perceptual deterrence literature examines the relationships of perceived sanction risks to either self-reported offending or intentions to do so. This literature was spawned by researchers interested in probing the perceptual underpinnings of the deterrence process.

Perceptual deterrence studies have focused on examining the connection of illegal behavior to two categories of sanction variables, the certainty and severity of punishment. The certainty of punishment refers to the probability that a crime will result in punishment whereas severity refers to the seriousness of the consequences to the punished individual, such as prison sentence length.

Perceptual deterrence studies have been based on three types of data: cross-sectional survey studies, panel survey studies, and scenario-based studies. In cross sectional survey studies individuals are questioned about their perceptions of the certainty and severity of sanctions and either about their prior offending behavior or future intentions to offend. For example, Grasmick and Bryjak (1980) queried a sample of city residents about their perceptions of the risk of arrest for offenses such as a petty theft, drunk driving, and tax cheating, and also about their intention to commit each of these acts in the future.

In panel survey studies the sample is repeatedly surveyed on risk perceptions and criminal behavior. For example, Paternoster et al. (1982) followed a sample of students through their three-year tenure in high school and surveyed the students on the frequency with which they engaged in various delinquent acts and their perceptions of the risks and consequences of being caught for each such acts.

In scenario-based studies individuals are questioned about their perceptions of the risks of committing a crime described in a detailed crime vignette and about their own behavior if they found themselves in that situation. Nagin and Paternoster (1993), for instance, constructed a scenario describing the circumstances of a date rape and surveyed a sample of college males about their perceptions of the risk of the scenario male being arrested for sexual assault and also about what they themselves would do in the same circumstance.

The cross-sectional and scenario-based studies have consistently found that perceptions of the risk of detection and punishment have a negative, deterrent-like association with self-reported offending or intentions to do so. Such deterrent-like associations with perceived severity are somewhat less consistent, but when individual assessments of the cost of such sanctions are taken into account, statistically significant negative associations again emerge. Only in the panel-based studies have null findings on deterrent-like effects been found.

In panel-based studies respondents were typically interviewed on an annual cycle. With these data researchers examined the relationship of behavior between years t and t 1 to risk perceptions at the outset of year t. Their purpose was to avoid the problem of causal ordering: Is a negative association a reflection of the deterrent impact of risk perceptions on crime or of the impact of criminal involvement on risk perceptions? Generally, these studies have found only weak evidence of deterrent-like associations (Paternoster 1987).

The null findings from the panel-based studies generated a spirited debate on the appropriate time lag between measurements of sanction risk perceptions and criminal involvement. Grasmick and Bursik (1990) and Williams and Hawkins (1986) have argued that ideally the measurements should be made contemporaneously because perceptions at the time of the act determine behavior.

The argument for temporal proximity is compelling but the challenge is its practical achievement. People cannot be queried on their risk perceptions on a real-time basis as they encounter criminal opportunities in their every day lives. The scenario method offers one solution because respondents are not questioned about their actual behavior or intentions but rather are asked about their likely behavior in a hypothetical situation. On average, persons who perceived that sanctions were more certain or severe reported smaller probabilities of their engaging in the behavior depicted in the scenario, whether it be tax evasion (Klepper and Nagin 1989), drunk driving (Nagin and Paternoster, 1993), sexual assault (Bachman et al. 1992), or corporate crime (Paternoster and Simpson 1997). Thus, it seems that a consensus has emerged among perceptual deterrence researchers in support of this position.

This consensus reframes the question of the deterrent effect of sanctions from the issue of whether people respond to their perceptions of sanction threats to the issue of whether those perceptions are grounded in reality. The literature on the formation of sanction risk perception is small and narrow in scope (Nagin 1998). The dearth of evidence on the policy-to-risk-perceptions linkage also leaves unanswered a key criticism of skeptics of the deterrent effects of official sanctions. Even if crime decisions are influenced by sanction risk perceptions, as the perceptual deterrence literature strongly suggests, absent some linkage between policy and perceptions, however imperfect, behavior is immune to policy manipulation. In this sense behavior lacks rationality, not because individuals fail to weigh perceived costs and benefits, but because the sanction risk perceptions are not anchored in reality.

1.2.2 The Linkage Between Formal And Informal Sanction Processes. Arguably the most important contribution of the perceptual deterrence literature does not involve the evidence it has amassed on deterrence effects per se. Rather it is the attention it has focused on the linkage between formal and informal sources of social control. Recognition of this connection predates the perceptual deterrence literature. For instance, Zimring and Hawkins (1973, p. 174) observe that formal punishment may best deter when it triggers informal sanctions: ‘Official actions can set off societal reactions that may provide potential offenders with more reason to avoid conviction than the officially imposed unpleasantness of punishment.’ See also Andenaes (1974) for this same argument.

Early perceptual deterrence studies did not consider the connection between formal and informal sanctioning systems but a review by Williams and Hawkins (1986) prompted a broadening of the agenda to consider this issue. Their position was this: Community knowledge of an individual’s probable involvement in criminal or delinquent acts is a necessary precondition for the operation of informal sanction processes. Such knowledge can be obtained from two different sources: Either from the arrest (or conviction or sentencing) of the individual or from information networks independent of the formal sanction process (e.g., a witness to the crime who does not report such knowledge to the police). Williams and Hawkins observe that deterrent effects may arise from the fear that informal sanctioning processes will be triggered by either of these information sources. They use the term ‘fear of arrest’ to label deterrent effects triggered by the formal sanction process and the term ‘fear of the act’ to label deterrent effects triggered by information networks separate from the formal sanction process. The crux of their argument is that all preventive effects arising from ‘fear of arrest’ should be included in a full accounting of the deterrent effect of formal sanctions.

Much of scenario-based research confirms their argument. This research has consistently found that individuals who report higher stakes in conventionality are more deterred by perceived risk of exposure for law breaking. A salient finding in this regard concerns tax evasion. In Klepper and Nagin (1989) a sample of generally middle-class adults were posed a series of tax noncompliance scenarios. The amount and type of noncompliance (e.g., over-stating charitable deductions or understating business income) was experimentally varied across tax return line items. The study found that a majority of respondents reported a non-zero probability of taking advantage of the noncompliance opportunity described in the scenario. Plainly, these respondents were generally willing to consider tax noncompliance when only their money (and not their reputation) was at risk. They also seemed to be calculating; the attractiveness of tax noncompliance gamble was inversely related to the perceived risk of civil enforcement.

The one exception to the rule of confidentiality of enforcement interventions is criminal prosecution. As with all criminal cases, criminal prosecutions for tax evasion are a matter of public record. Here there was evidence of a different decision calculus; seemingly all that was necessary to deter evasion was the perception of a non-zero chance of criminal prosecution. Stated differently, if the evasion gamble also involved putting reputation and community standing at risk, middleclass respondents were seemingly unwilling to consider taking the noncompliance gamble.

The tax evasion research does not pin down the specific sources of stigma costs, but other research on the impact of a criminal record on access to legal labor markets suggests a real basis for the fear of stigmatization (Freeman 1995, Waldfogel 1994). Freeman estimates that a record of incarceration depresses probability of work by 15 percent to 30 percent and Waldfogel estimates that conviction for fraud reduces income by as much as 40 percent.

1.3 Ecological Studies

Two broad classes of ecological analyses are considered—studies of the deterrent effect of prison and of the police.

1.3.1 The Impact Of Prison Population On Crime Rate. Except for capital punishment, prison is the most severe and costly sanction. Except for a flurry of flawed studies in the 1970s, however, there have been few studies of the impact of this sanction. The paucity of studies is attributable to the problem of untangling cause from effect in statistical analyses of natural variation in crime rates and sanction levels as measured by indicators like prisons per capita or actual time served in prison. For example, all else equal, more crime will increase the incarceration rate. However, all else is not equal because a larger prison population will tend to reduce the crime rate. In statistical parlance, the problem of sorting out these contending impacts is called identification (Blumstein et al. 1978, Fisher and Nagin 1978).

At least one study has plausibly dealt with the identification problem. Levitt (1996) employs a clever identification strategy based on measuring the impacts on crime rates of court orders to reduce prison overcrowding. He estimates that 15 index crimes are averted for each additional man-year of imprisonment.

Can a study such as that conducted by Levitt provide an all-purpose estimate of the impact of prison population on crime rate. The answer, I believe, is no. Specifically, there is good reason for believing that policies producing equivalent changes in the prison population will not result in the same change in crime rate.

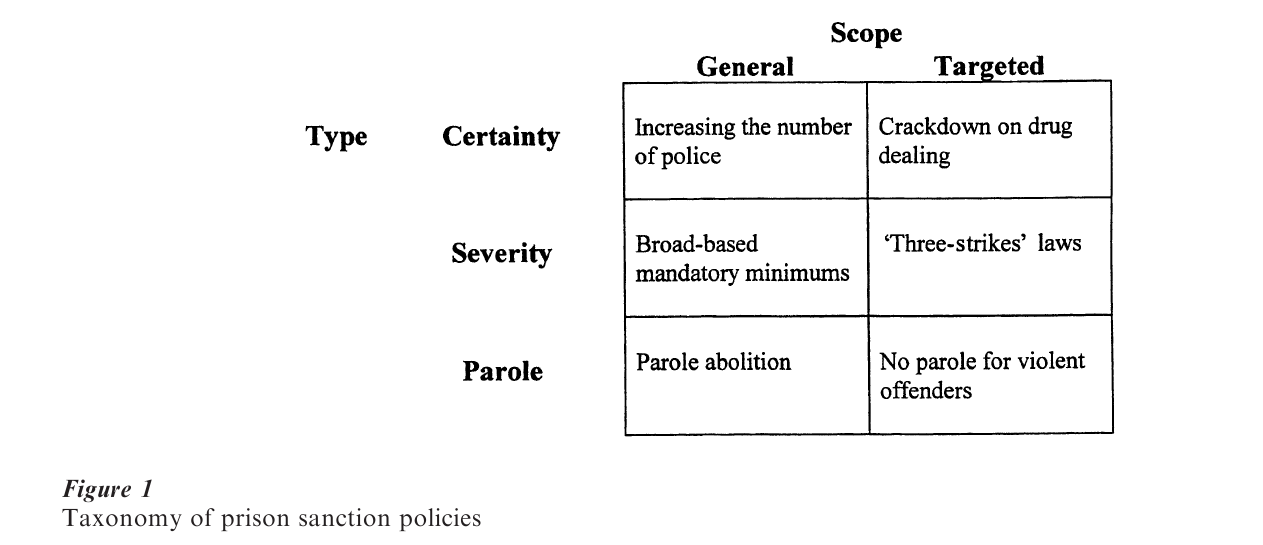

Figure 1 is a two-dimensional taxonomy of sanction policies affecting the scale of imprisonment. One dimension labeled ‘Type’ distinguishes three broad categories. Policies regulating certainty of punishment such as laws requiring mandatory imprisonment, policies influencing sentence length such as determinate sentencing laws, and policies regulating parole powers. The second dimension of the taxonomy, ‘Scope,’ distinguishes policies that cast a wide net, such as a general escalation of penalties for broad categories of crime, compared to policies that focus on targeted offenses (e.g., drug dealing) or offenders (e.g., ‘three-strikes’ laws).

The Levitt study is based on US data during a period in which the imprisonment rate more than quadrupled. This increase was attributable to a combination of policies belonging to all cells of this matrix. Parole powers have been greatly curtailed, sentence lengths increased, both in general and for particular crimes (e.g., drug dealing), and judicial discretion to impose nonincarcerative sanctions has been reduced (Tonry 1995). Consequently, any impact on the crime rate of the increase in prison population reflects the effect of an amalgam of potentially interacting policies. By contrast the impact estimated in the Levitt study measures the preventive effect of reductions in the imprisonment rate induced by the administrative responses to courts orders to reduce prison populations. Thus, his estimate would seem only to pertain to policies affecting parole policies.

1.3.2 The Impact Of Police On Crime Rate. The largest body of evidence on deterrence in the ecological literature focuses on the police. The earliest generation of studies on the deterrent effect of police examined the linkage of crime rate to measures of police resources (e.g., police per capita) or to measures of apprehension risk (e.g., arrest per crime). These studies were inadequate because they did not credibly deal with the identification problem. If the increased crime rates spur increases in police resources, as seems likely, this impact must be taken into account to obtain a valid estimate of the deterrent effect of those resources.

A study by Wilson and Boland (1978) plausibly identifies the deterrent effect of the arrest ratio. They argued that the level of police resources per se is, at best, only loosely connected to the apprehension threat they pose. Rather the crucial factor is how the police are mobilized to combat crime; Wilson and Boland argue that only proactive mobilization strategies will have a material deterrent effect. In their words (1978, p. 373), ‘By stopping, questioning, and otherwise closely observing citizens, especially suspicious ones, the police are more likely to find fugitives, detect contraband (such as stolen property or concealed weapons), and apprehend persons fleeing from the scene of a crime.’ They conclude that the arrest ratio has a substantial deterrent effect on robbery.

An important follow-up to the Wilson and Boland study was conducted by Sampson and Cohen (1988). Their key premise was similar to that of Wilson and Boland—‘hard’ policing of ‘soft’ crime such as prostitution, drunkenness, and disorderly conduct deters serious criminality—and their findings supported the deterrent impact of this policing strategy.

An important innovation in Sampson and Cohen is that they not only estimate a population-wide deterrent effect but disaggregate this effect across segments of the population—white juveniles, black juveniles, white adults, and black adults. They do this by using arrest rates as surrogate measures of demographic group-specific offense rates. They find a negative deterrent-like association between aggressiveness and arrest rate for all groups but they also find significant differences by race and age in the magnitude of the effect. For robbery, at least, adults seems to be more deterred by police aggressiveness than do juveniles, with black adults seemingly more deterrable than white adults. Because the results for specific demographic groups are based on arrest rates, they must be qualified in a number of obvious ways. Notwithstanding, disaggregation efforts are laudable and should, where feasible, become standard in deterrence studies.

1.4 Summary Observations On Deterrence

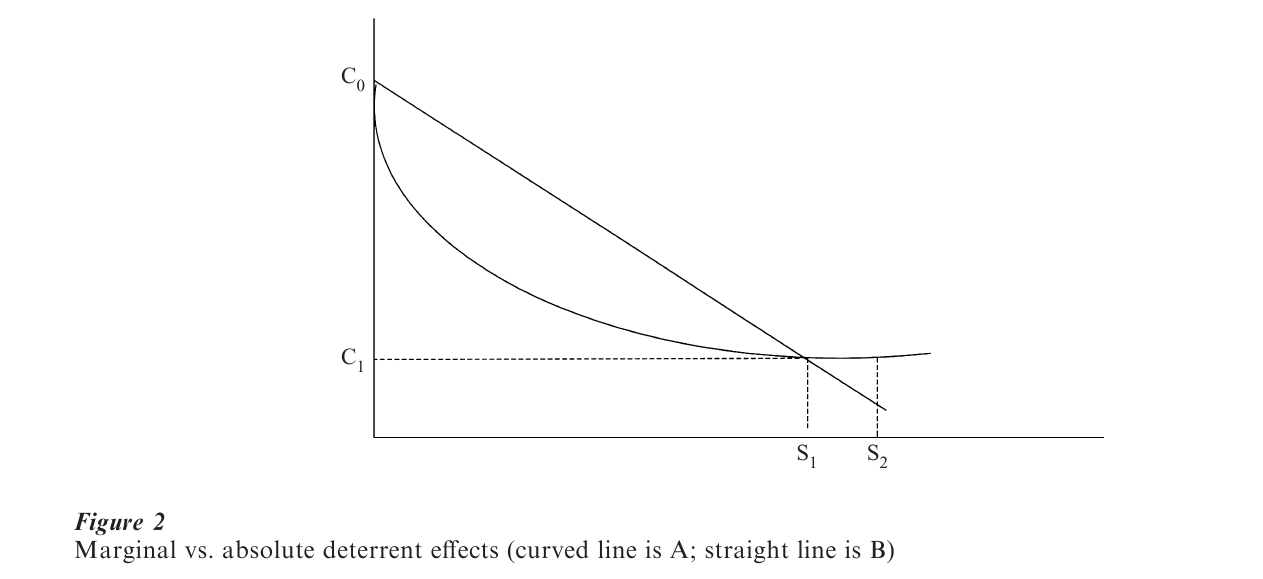

At the outset, it was stated that the accumulated evidence on deterrence leads me to conclude that the criminal justice system exerts a substantial deterrent effect. That said, it is also my view that this conclusion is of limited value in formulating policy. Policy options to prevent crime generally involve targeted and incremental changes. So for policy makers the issue is not whether the criminal justice system in its totality prevents crime, rather it is whether a specific policy, grafted onto the existing structure, materially adds to the preventive effect. Here there is a distinction drawn between absolute and marginal deterrence. Figure 2 depicts two alternative forms of the response function relating crime rate to sanction levels. Both are downward sloping, which captures the idea that higher sanction levels prevent crime. At the status quo sanction level, S , the crime rate, C , is the same for both curves. The curves are also drawn so that they predict the same crime rate for a zero sanction level. Thus, the absolute deterrent impact of the status quo sanction level is the same for both curves. But because the two curves have different shapes, they also imply different responses to an incremental increase in sanction level to S . The response implied by curve A is small. Accordingly, it would be difficult to detect and likely not sufficient to justify the change. By comparison, the response depicted in curve B is large, thus more readily detectable, and also more likely to be justifiable as good policy.

While the distinction between absolute and marginal deterrence is useful, it implies an underlying analytical simplicity of the relationship of crime rates to sanction levels that belies the complexity of the phenomenon. Contrary to the implicit suggestion of Fig. 2, no one curve relates sanction levels to crime rates. The response of crime rates to a change in sanction policy will depend on the specific form of the policy, the context of its implementation, the process by which people come to learn of it, differences among people in perceptions of the change in risks and rewards that are spawned by the policy, and by feedback effects triggered by the policy itself (e.g., a reduction in private security in response to an increase in publicly funded security). Thus, while a number of studies have credibly identified marginal deterrent effects, it is difficult to generalize from the findings of a specific study because knowledge about the factors that affect the efficacy of policy is so limited. Specifically, there are four major impediments to making confident assessments of the effectiveness of policy options for deterring crime.

First, while large amounts of evidence have been amassed on short-term deterrent effects, little is known about long-term impacts. Evidence from perceptions-based deterrence studies on the interconnection of formal and informal sources of social control point to a possibly substantial divergence between long-and short-term impacts. Specifically, these studies suggest that the deterrent effect of formal sanctions arises principally from fear of the social stigma that their imposition triggers. Economic studies of the barriers to employment created by a criminal record confirm the reality of this perception. If fear of stigma is a key component of the deterrence mechanism, such fear would seem to depend upon the actual meting out of the punishment being a relatively rare event: Just as the stigma of Hester Prynne’s scarlet ‘A’ depended upon adultery being uncommon in Puritan America, a criminal record cannot be socially and economically isolating if it is commonplace. Policies that are effective in the short term may erode the very basis for their effectiveness over the long run if they increase the proportion of the population who are stigmatized. Deterrence research has focused exclusively on measuring the contemporaneous impacts of sanction policies. Long-term consequences have barely been explored.

The second major knowledge gap concerns the connection of risk perceptions to actual sanction policy. The perceptual deterrence literature was spawned by the recognition that deterrence is ultimately a perceptual phenomenon. While great effort has been committed to analyzing the linkage between sanction risk perceptions and behavior, comparatively little attention has been given to examining the origins of risk perceptions and their connection to actual sanction policy.

For several reasons this imbalance should be corrected. One is fundamental: the conclusion that crime decisions are affected by sanction risk perceptions is not a sufficient condition for concluding that policy can deter crime. Unless the perceptions themselves are manipulable by policy, the desired deterrent effect will not be achieved. Beyond this basic point of logic, a better understanding of the policy-to-perceptions link can also greatly aid policy design. For instance, nothing is known about whether the risk perceptions of would-be offenders for specific crimes are formed principally by some overall sense of the effectiveness of the enforcement apparatus or by features of the apparatus that are crime specific (e.g., the size of the vice squad or the penalty for firearms use). If it is the former, seemingly targeted sanction policies will have a generalized salutary impact across crime types by heightening overall impressions of system effectiveness. If the latter, there will be no such generalized impact. Indeed would-be offenders may substitute non-targeted offenses for targeted offenses (e.g., committing burglaries in response to increased risk for robbery).

Third, the impact of specific policies—e.g., increasing the number of police—will depend on the form of its implementation across population units. Yet estimates of the deterrent effect of such policies from the ecological literature are commonly interpreted as if they apply to all units of the population from which they were estimated. In general this is not the case. Rather the estimated deterrent effect should be interpreted as the average of the ‘treatment’ effect across population units. For instance, the deterrent impact of more police in any given city will depend upon a host of factors including how the police are deployed. Consequently, the impact in any given city will not be the same as the average across all cities; it may be larger, but it could also be smaller. Similarly, it is not possible to make an all-purpose estimate of the impact of prison on crime. There are many ways to increase prison population by a given amount, ranging from broad-based policies such as across-the-board increases in sentence length to targeted policies like ‘three strikes’ statutes. It is likely that the magnitude of the preventive effect will vary materially across these options. The implication is that even though there are credible estimates of average deterrent effects of at least some broad classes of policies, the capacity to translate the average estimates into a prediction for a specific place is limited. This is a major shortcoming in the evidence because crime control is principally the responsibility of state and local government. It is the response of crime to policy in that city or state that is relevant to its population, not the average response across all cities and states.

Bibliography:

- Andenaes J 1974 Punishment and Deterrence. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Bachman R, Paternoster R, Ward S 1992 The rationality of sexual offending: Testing a deterrence rational choice conception of sexual assault. Law & Society Review 26: 401

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Canella-Cacho J 1993 Filtered sampling from populations with heterogenous event frequencies. Management Science 37(4): 886–98

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Nagin D (eds.) 1978 Deterrence and Incapacitation: Estimating the Effects of Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

- Fisher F M, Nagin D 1978 On the feasibility of identifying the crime function in a simultaneous model of crime rates and sanction levels. In: Blumstein A, Cohen J, Nagin D (eds.) Deterrence and Incapacitation: Estimating the Effects of Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

- Freeman R 1995 Why do so many young American men commit crimes and what might we do about it? Journal of Economic Perspectives 10(1): 25–42

- Grasmick H G, Bryjak G J 1980 The deterrent effect of perceived severity of punishment. Social Forces 59: 471

- Grasmick H G, Bursik R J Jr 1990 Conscience, significant others, and rational choice: Extending the deterrence model. Law Society Review 24: 837–61

- Klepper S, Nagin D 1989 The deterrent effect of perceived certainty and severity of punishment revisited. Criminology 27: 721

- Levitt S 1996 The effect of prison population size on crime rates: Evidence from prison overcrowding litigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 111: 319–52

- Levitt S 1998 Criminal Deterrence Research: A Review of the Evidence and a Research Agenda for the Outset of the 21st Century. In: Michael Tonry (ed.) Crime and Justice: A Review of Research.

- Nagin D, Paternoster R 1993 Enduring individual differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law and Society Review 27(3): 467–96

- Paternoster R 1987 The deterrent effect of the perceived certainty and severity of punishment: A review of the evidence and issues. Justice Quarterly 4: 173–217

- Paternoster R, Saltzman L E, Chiricos T G, Waldo G P 1982 Perceived risk and deterrence: Methodological artifacts in perceptual deterrence research. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 73: 1238–58

- Paternoster R, Simpson S 1997 Sanction threats and appeals to morality: Testing a rational choice theory of corporate crime. Law and Society Review

- Ross H L 1982 Deterring the Drinking Driver: Legal Policy and Social Control. Heath, Lexington, MA

- Sampson R J, Cohen J 1988 Deterrent effects of police on crime: A replication and theoretical extension. Law and Society Review 22: 163–89

- Sherman L W 1990 Police crackdowns: Initial and residual deterrence. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds.) Crime and Justice: A Review of Research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Vol. 12

- Tonry M 1995 Neglect, Race, Crime, and Punishment in America. Oxford Press, New York

- Waldfolgel J 1994 The effect of criminal conviction on income and the trust reposed in the women, Journal of Human Resources Winter

- Williams K R, Hawkins R 1986 Perceptual research on general deterrence: A critical overview. Law and Society Review 20: 545–72

- Wilson J Q, Boland B 1978 The effect of the police on crime. Law and Society Review 12: 367–90

- Zimring F E, Hawkins G J 1973 Deterrence: The Legal Threat in Crime Control. University of Chicago, Chicago